Islam in Africa

Islam in Africa has existed in the countries along the Mediterranean coast since the 7th century through the expansion of the Umayyads . It was not until the middle of the 19th century that traders and missionaries brought Islam to Uganda . The forms of Islam on the continent are just as varied as the spread over time. The majority of Muslims in Africa are Sunni , they also include followers of Sufism , who have contributed greatly to the awareness and cult practice of Islam since its early spread. Influences from African beliefs shaped their own orthodoxy, which increased the diversity of the religion and constituted a cultural tradition.

Organizations close to the Wahhabis try to narrow down African Islam to a puritanical direction through re-Islamization.

According to various sources, 43 to 45 percent of all Africans are Muslim. Half of African Muslims do not speak Arabic, but one of the many languages on the continent. Islam became part of African culture. Almost a quarter of all Muslims worldwide come from Africa.

History of spread

North africa

Mission wars were not an Islamic strategy. The military incursion into North Africa was aimed at the expansion of rule and not conversion with "fire and sword". In 639 Amr ibn al-As invaded Egypt with an army of 4,000 Muslims , and within three years the richest Byzantine province was conquered. In the years that followed , the force conquered the entire African Mediterranean coast. Against little resistance they reached the fertile arable land of today's Tunisia in 647 and founded Kairouan there in 670 as the capital of the new province of Ifrīqiya . The years in between served the successor dispute over the caliphate. Shortly afterwards the supposed end of the world was reached on the Atlantic. The only, but bitter resistance came from the Berbers , who made up the largest group in the army of Muslims when Spain was conquered from 711 onwards.

The subjugated, already Christianized peoples had the opportunity to accept the new faith or to become tributaries as dhimmi . The conquerors were soon followed by immigrants. At the beginning of the 8th century there were so many Arabs in Egypt that the Copts could be excluded from the administration and Arabic became the official language.

Out of respect for the archers of the Christian Nubians , the rule was not extended southwards into Sudan . The 652 ceasefire was to the advantage of those involved for the next 500 years. Arabs settled in the Christian kingdoms as traders and from the 10th century also as cattle breeders. The main export goods from Nubia were slaves. It was not until 1317 that the Dongola Cathedral was converted into a mosque.

The Arab caliphate of the Umayyads , whose ruling family came from Mecca, was replaced in 750 by the Arab Abbasids , who were also based on the former Sassanid Empire . A rebellion in Tangier in 740 contributed to the overthrow of the Umayyads in Africa , which was instigated by Kharijites among once Christian Berbers. Kharijites were among the first radical movements in Islam. They had to flee from Arabia in 714 and formed fanatical communities during the Abbasid rule in the mountains of Algeria and Morocco , after 761 even with their own state.

The Shiite - Ismaili dynasty of the Fatimids , which came to power through a Berber uprising in Kairouan in 910, was the Berber response to the Arab conquest. Their beliefs were less radical. The flourishing empire with the capital Cairo was overthrown by Saladin in 1171 after being weakened by the Crusaders . This ended the peaceful trade relations with Nubia.

In the meantime, nomadic Berber tribes came to power in the west. The nomadic Sanhaja Berber gathered around a group of religious zealots from the Maliki school of law who had withdrawn from the Senegal River with their leader Ibn Yasin († 1059) . They were missionary, devout Muslims who called themselves Murabitun and in the 11th century united Morocco and southern Spain as the Almoravid Empire. Their empire went under at the end of the same century, Murabitun (singular: Murabit, "people of the fortress") are still on the road as Islamic front fighters, that is, as traveling preachers.

The counter-movement arose among the Berber farmers and brought the mysticism of Sufism to the Atlas Mountains . The Almohads ("confessors of the unity of God") led a strict Islamic rule with a puritanic belief from 1147 to 1269, under which Christianity in the Maghreb was almost exterminated. The Sufi brotherhoods that were promoted from the end of the 12th century remained.

Sub-Saharan

The black African empire of Ghana was hospitable to the Almoravids in the 11th century. The nomads were allowed to create their own districts in the northernmost trading town of the Aoudaghost Empire . Since they did not want to live under the rule of an unbeliever, the Almoravids stormed and devastated the place in 1054/55 and conquered the alleged capital Koumbi Saleh in 1076 . The population later converted to Islam, but the empire no longer recovered.

This is an exception: West Africa was predominantly Islamized not through conquest, but through trade. Most traders in the 10th century were Muslim. Berber and Tuareg traders brought Islam from the Maghreb via the Trans-Saharan trade routes. From the old Ghana Empire in the west, Muslim traders of the Soninke and Diola were on their way south to the large trading centers of central Niger Djenné , Timbuktu and Gao . At the beginning of the 14th century, the Mali Empire was officially an Islamic state, which included the ruler's pilgrimage to Mecca. The heroic founder of Mali, Sundiata Keïta (around 1180–1255 / 60), was nominally a Muslim; his son Mansa Ulli made the first royal pilgrimage. The pilgrim kings strengthened their power through Islam, but rituals of traditional belief were still practiced and Islam remained alien. Mansa Musa (ruled 1312–1332) used the Shari'a for his purposes, employed an Egyptian imam for the Friday sermon and continued to have the ancient animistic ceremonies held at his court. At his instigation, the Djinger-ber Mosque , which is now a world heritage site, is said to have been built in Timbuktu.

Ibn Battuta admired the “zeal for prayer” of the population in 1352/53 and at the same time was amazed at certain pagan practices such as mask dances, self-humiliation in front of the king, eating unclean food and the poor clothing of women. A setback for Islam was the first ruler of the Songhairian kingdom Sonni Ali (ruled 1465–1492), who broke away from Mali rule. Although he was nominally Muslim, he practiced a pronounced ancestral cult, persecuted the religious scholars ( ulama ) and threw them out of the country. Simplifying, he was contrasted as the “magical king” with the “pilgrim king” of Mali. His successor, the military Askiya Muhammad , soon went on a pilgrimage.

Generally speaking, in order to maintain their power, kings protected all religions of their subjects. In the 11th century, the rulers of the empires of Gao, Mali, Ghana, Takrur (see Tukulor ) and Kanem converted to Islam. By the 17th century, Islam had arrived in every West African state.

In contrast to the Mali empire, whose king Mansa Musa wasted vast amounts of gold on his pilgrimage in Egypt, the economic power of the Kanem empire north of Lake Chad, which had existed since the 6th century, was not based on gold, but on slaves who were after salt and horses the north were traded. Despite the long trade contacts, Islam did not begin to spread until the 11th century. Initially a pastoral state, the capital was relocated to Bornu in the 14th century on the plains southwest of Lake Chad, which are more suitable for agriculture. The empire was ruled by mounted warriors who demanded tribute from the farming villages. At the height of power, the warrior king Idris Aluma (1571-1603) led permanent campaigns of conquest against his neighbors. His administrative reforms included the introduction of Sharia law . He was known for his piety, had mosques built and made a pilgrimage to Mecca. Thanks to sufficient rainfall for agriculture, easily captured slaves in the south and the awareness of being culturally superior through one's religion, a 1000-year dynasty existed until the beginning of the colonial era in the 19th century.

Horn of Africa

The Ethiopian Muslims claim to be the successors of the oldest Islamic community in Africa. In the first six centuries AD there was a kingdom in northern Ethiopia with the capital Aksum and the port city of Adulis . The kingdom was known to the Arab tribe of the Koreishites on the opposite side of the Red Sea through trade connections . Mohammed also belonged to this tribe . The Prophet had a threefold connection to the country of the Ethiopians: his ancestors included an Ethiopian woman, his wet nurse was a freed Ethiopian slave and there was the Ethiopian maid Baraka (Umm Ayman).

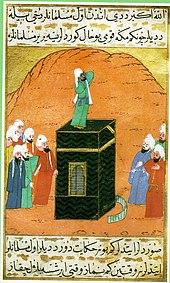

According to Islamic tradition, 615 members of Muhammad's family and a few converts sailed by boat to Adulis, found refuge from persecution in Aksum, and received permission from the Christian ruler to settle. This emigration preceded the actual Hijra to Medina in 622 , so it took place before the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

In the following centuries after the establishment of trading posts along the coast, settlements of Somalis and other Kushite peoples were Islamized to the edge of the Ethiopian highlands. Slaves, gold and ivory were obtained from the Christian highlands and exchanged for salt from the lowlands and luxury goods. Small Islamic principalities emerged in the 12th century. From the 13th century onwards, the Harari sultanates united to form an Islamic empire in eastern Ethiopia. The capital Harar with countless mosques and Sufi shrines is considered the fourth holiest Islamic city by Ethiopian Muslims.

East African coast

In Ethiopia nothing has survived from the early Islamic period, trade contacts from the early days to settlements on the East African coast are considered likely. The earliest remains of an Islamic settlement south of the Sahara were found in Shanga on the Kenyan island group of Lamu . There the post holes of a wooden mosque that is dated to the 8th century were excavated . Since the mosque did not have a mihrab and was still oriented towards Jerusalem, even dating during Muhammad's lifetime is being considered.

From the 8th century, temporary stations were initially set up along the coast in order to wait for favorable winds for the return journey of the sailing boats . This resulted in the first Arab settlements between Lamu, Zanzibar and the island of Kilwa . Donations came from wealthy Arab countries, which means that by the 11th century mosques were built as stone buildings in at least eight coastal settlements.

Trade with China brought the Kilwa dynasty to its prime in the 14th century. Kilwa's rulers had the Great Mosque expanded and made a pilgrimage to Mecca. These city-states confined themselves to a narrow coastal fringe and did not seek political power inland. Islam and the Swahili culture of the coastal population were only spread along the trade routes. The Portuguese first appeared on the East African coast around 1500, and at the end of the 17th century they gradually lost their trading centers Mombasa and Kilwa and the religious dispute against the Muslim Arabs and Swahili. The Sultanate of Oman expanded economically and from the middle of the 18th century also with a claim to political dominance on the East African coast. In 1840 the capital of the sultanate was moved to Zanzibar. The judiciary was carried out during their rule to avoid conflict in equal parts by an Ibadi (the predominant religious school in Oman) and Sunni Kadi . Sunnis of the Shafiite law school from the Hadramaut had already from the 12./13. Settled on the coast in the 19th century.

Paradoxically, the Ibadite sultans of Zanzibar contributed particularly to the spread of Sunni Islam. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Sultanate of Zanzibar took neighboring islands such as Lamu and Pate , as well as Mombasa . Many Swahili Muslims were displaced as a result and established new settlements on the coast and inland, which brought them more into contact with non-Muslims. In the 1870s, rural Islamization began, first around Arab-laid farmsteads (such as the slave-operated sugar cane plantation on the Pangani River ). Since the caravan routes along which Islam spread to Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria ran in the plains and avoided the mountains, the first Christian missionaries began their work in the mountains. Nothing has changed in Tanzania in terms of the distribution of the two religions that resulted.

From the 1890s, traders and some revered Islamic scholars (sheikhs) brought Islam to Mozambique and from the east coast into the interior of Malawi (→ Islam in Malawi ). For the Muslims of both countries, the Sultan of Zanzibar represented the center of Islamic learning. Muslims in Mozambique called the name of Sultan Bargash ibn Said (1870–1888) during Friday prayers. The Catholic Portuguese behaved very restrictively towards the Muslims in their colony and refused any support, in contrast to the tolerant religious policy of the British in Malawi.

Sudan I

In 1504 the Black African Sultanate of Funj was established in Sudan , whose center was in Gezira and which was recognized in the north as far as Upper Nubia . Christianity had disappeared in Nubia two centuries earlier through Arabization . Under the Islamic Funj rule, legal scholars ( ulama ) and marabouts were brought into the country from the Hejaz , whose rivalry is particularly evident in Sudan to this day.

After the Sufi brotherhoods of Qadiriyya and Shadhiliyya, which dominated in the 19th century, and after the conquest of the Funj Empire in 1821 by Turkish Egypt , reformist salvation teachings began to spread their influence. Around 1818 to 1820 the Khatmiyya - Tariqa was introduced by its founder Mohammed 'Uthman al-Mirghani (al Chatim), which spread among his successors in the north and east of the country and has considerable political influence to this day.

At the center of another new doctrine was the expected end-time Mahdi , who would fight evil and create a purified world. In 1881 the Mahdi appeared in the form of Muhammad Ahmad (1843-1885), a student of the Sammaniyya Tariqa, who proclaimed jihad against the infidels (he meant the Turkish-Egyptian occupation) and whose theocratic state was defeated in 1898 by Anglo-Egyptian troops . A newly established successor organization to the Mahdi ( Ansar , "helper") gained great economic influence from the 1930s and grew from a fanatical movement to a still significant force in Sudan today.

In the 1950s, a Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood (short name Ichwan , "Brotherhood"), independent of Egypt , appeared. From 1977 Numairi , who had come to power as the president of a left-wing government in 1969, began an ideological turn to Islam. In 1983 Numairi introduced the Sharia laws. From 1985 a strict Islamization began by the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood Hasan at-Turabi , including the separation of men and women in public life, the introduction of an Islamic dress code and state doctrine, which not only fueled the clashes with the Christian southern part of Sudan, but also fueled contradictions Republican Islamic circles aroused. The organization of the Republican Brothers tried to oppose the introduction of the Sharia. Its founder Mahmud Muhammad Taha spoke of the ability of Koranic beliefs to develop, emphasized their historicity and the interpretability of the Sharia. In 1985 he was executed for sedition and apostasy .

South Africa

In 2008, almost two percent of the population in South Africa was Muslim; in 1840, 6400 Muslims made up a third of the population of Cape Town . Sheikh Yusuf al-Taj al-Chalwati al-Maqasari, named after his homeland Sheikh Yusuf of Makassar , is considered to be the founder of the Islamic community , an Islamic scholar and sufi mystic who fled from Indonesia in 1694 from Dutch colonial rule or who was deported by the same, who is now venerated as a saint . The first Indonesian Muslims were brought here from the island of Ambon as early as 1658 to defend the Dutch settlements from the Khoi Khoi . In the 17th and 18th centuries, Islam was spread in South Africa by workers, (political) convicts and slaves of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). In 1667 three Sufi sheikhs came from Indonesia in a group of over 1,000 political prisoners from the VOC. Private practice of religion was allowed to the slaves. The sheikhs secretly spread their (presumably) Qadiriyya doctrine in private homes, a madrasa was opened in 1793 and the first mosque around 1800.

Islamic Faiths in Africa

Through certain ritual practices such as Friday prayer, the maintenance of Islamic holidays or the annual pilgrimage to a holy grave, different forms of faith can construct a community. A distinction between urban orthodox tradition of the elites and a local practice of the rural population with veneration of saints is considered to be outdated. Instead, one should speak of different teachings of Islam of equal value.

Law schools

Of the four law schools ( Madhahib ) of Sunni Islam, the conservative Malikite school from Medina was the first to prevail in Sudan, most of North Africa and further in West African countries such as Mauritania and Ghana .

Shafiites are most widespread in Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia . On the East African coast, too, the Shafiites from the countries of southern Arabia were able to form a majority thanks to their trade connections. They are in opposition to the most conservative school of the Hanbalites , which is practiced almost exclusively in Saudi Arabia.

In the Horn of Africa , the schools of law have spread over small areas: There are some Hanafis in Eritrea and parts of Ethiopia , including a district of Harar ( Ottoman influence. The rest of the city is Shafiite). Ibadites are only found in small groups in Algeria (there the Berber Mozabites ) and by the earlier Omani rulers on Zanzibar.

In East Africa there are some Ismailis , especially among the Indian population , in whose esoteric belief the seventh Imam Ismail is venerated. After the Iranian Revolution in 1979, a flood of proselytizing brochures from Iran brought about a politicization of Islam and a slightly increasing number of Shiite believers.

Sufism in Africa

Religious practices are judged on whether they are effective. Faith is based on collective experience. According to Islamic tradition, this mystical current already existed in the time of Muhammad. At the same time and in association with the Arab conquerors and traders, Islam and the Sufi faith came to the countries of Africa. Soon goods and religion were taken over by African traders and transported on. Many of the traders were members of Sufi brotherhoods ( Tariqa , plural: Turuq ), which could trace their special blessing power ( Baraka ) back to the family of the Prophet. As fortune tellers, interpreters of dreams and faith healers, the teachers of the faith were also accepted in remote areas. In the Sudan region , according to travel descriptions from the 17th century, there were mendicant monks clad in goatskin, traveling alone, who were able to move through all ruled areas unmolested by armed conflicts. In the Maghreb they appeared organized as marabouts : religious fighters and missionaries who lived in monastery fortresses ( Ribāṭ ) and spread a popular Sufism among the only superficially Islamized Berbers . In North Africa, which is culturally dominated by Arabs, the veneration of saints came to the center of religious practice through Sufism. The more saints, the less widespread belief in angels is . In contrast, Sufism in sub-Saharan Africa, where Islamic magic is practiced among the people, has practically no knowledge of the North African grave cult.

Written mediators of the Koran to be read in Arabic - mediators between believers and God - replaced or supplemented the traditional healers. The faith that these Islamic scholars preach need not be less rigorous. In the case of Usman Dan Fodio and other reformers, Sufism was militant.

Important Turuq are the Qadiriyya, founded in the 11th century, and the Tijani ; the latter is an Islamic reform movement that spread from Morocco to West Africa from the end of the 18th century. Some Turuq were not re-founded out of the idea of religious reform, but split off among his students because of a succession dispute after the sheikh's death. The innumerable brotherhoods, many with only local influence, can be located on closely ramified family trees. One example is the Salihiyya , which developed from the Libyan order of Sanussiya in the 19th century through the Idrissiya of a Moroccan and the Rashidiyya of a Sudanese sheikh in northern Somalia .

Among the mausoleums of Sheikh annual pilgrimages are organized. A sheikh is understood to mean a saint, a venerated old man and usually also a political leader who spreads the teachings of his tariqa. Wali is another term used to describe a saint who has a reputation as a benefactor, helper, or friend. In contrast to the Christian understanding, Islamic saints are not canonized by an authority, but develop into such through veneration of their person in a local setting, some later gain in importance. After death, her tomb becomes a place of worship, as her baraka is supposed to continue working on the tomb. Their beneficial influence is based on a special power that is transferred to every student of an order by their teacher, precisely that chain of initiation ( Silsila ) that goes back to the Prophet himself . Learning this sequence by name is an important part of the training. The bodies of the deceased saints should not rot and at certain times emit a smell of musk or a light. If the grave is represented by a wooden structure hung with cloths, the damp earth underneath can also be a special sign. The usual ritual, with which the pilgrim would like to direct the power to a desired personal goal, consists of walking around the sanctuary seven times counterclockwise.

Beyond their religious significance, Sufi brotherhoods are social networks, alliances of trust for economic relationships and can - without any trance - exercise considerable political power. The classification as popular Islam is therefore incorrect. In the Maghreb, the Turuq are seen as the antithesis of radical Wahhabism and are supported by the state.

In Senegal , Islam - viewed by more recent Islamist tendencies - has so far been considered liberal. The first president after independence, Léopold Sédar Senghor , ruled a country with 95 percent Muslims for 20 years as a Christian. The four or five main brotherhoods are more powerful in Senegal than in any other country south of the Sahara. The marabouts of the Muridiyya , a reform movement that was founded by Amadou Bamba M'Backé (1850–1927) around 1900 and particularly appeals to urban youth, have a particular influence .

The Maghreb as the starting point for Sufi movements

In the 12th century, mystical Sufism experienced its heyday in northwest Africa. The focus was on Abu Madyan (1126–1198), the Islamic scholar, poet and today's patron of the Algerian city of Tlemcen , near which the Seville- born settled after long years of teaching and traveling. In Baghdad he is said to have met Rifa'i and learned Indian breathing techniques. Of his honorary titles - one is "Sheikh of the West" - Qutb (a central "axis" around which the earth rotates) refers most clearly to the importance of this saint, whose poems are recited in the Maghreb at the Dhikr . Ibn Arabi (1165–1240) - "the greatest sheikh" - got to know his teachings through one of Abu Madyan's favorite students . In contrast to Abu Madyan, whose miracles are told, Ibn ¡Arab∆ had no effect on the people; Ibn ¡Arab∆ developed from his extensive literature on Islamic philosophy and Christian mysticism.

A Puritan counter-movement, which primarily aimed at the self-image with which the Sufi mystics interpreted the Koran and criticized the freedom with which they approached God, put Sufism on the defensive as a whole. The spiritual leader against the decadence of saints cults and for religious renewal was Ibn Tumart (1077–1130), who gave the militant Berbers of the Almohad dynasty their moral foundation. When the Almohads had conquered the entire west, there were executions for blasphemy. One of the first victims was Abu Madyan. Many Sufis began to flee and their writings were burned. Sufism as a spiritual force hardly existed in the 14th century.

Sufism lived on in the people with the veneration of saints and pilgrimages, especially through the teachings of Abu-l-Hasan al-Shadhili (1196 / 1197–1258). In the western Rif Mountains , next to a cave, lies the grave of the saint and patron of the area, ʿAbd as-Salām ibn Maschīsch (1140-1227). A visit to his grave and the cave, from the ceiling of which drips water containing baraka , is considered a “little pilgrimage” and an equivalent substitute for the Hajj to Mecca. Abdeslam was one of the greatest Sufi teachers in the Maghreb, although little is known about himself. His teaching was spread throughout North Africa by his disciple Abu-l-Hasan al-Shadhili and is called Shadhiliyah after him . He fled persecution to Andalusia and later taught in Egypt, where he died in 1258.

The spread of the Schadhiliyya-Tariqa was facilitated by fixed rules of the order, which regulated the daily routine in the whole of North Africa in monastery-like centers. In the west it became fortified settlements ( Ribāṭ ) for religious fighters on the border to enemy territory, in the east the religious schools ( Khānqāh ) could develop into whole villages. Own farmland was leased to farmers who had to deliver the income. Some of the centers had their own tax sovereignty. They also received money from pious foundations. Mohammed ibn Sulayman al-Jazuli (1390s – 1465), who came from the Moroccan Merinid dynasty of the Berbers, was the innovator of the Schadhiliyya in the 15th century . Since he gave patriotic speeches in Marrakech and called for a fight against the Portuguese, he was allowed to spread the mysticism of his Jazuli doctrine at the same time. He is the most venerated saint of the Seven Saints of Marrakech . The successors in the home area of the Schadhiliyya were the Aissaoua at the end of the 15th century and the Nasiriyya brotherhood in the 17th century . Al-Dschazuli's student Abu Bakr ibn Muhammad (1537-1612) founded the Dila Brotherhood , whose Zawiya (center of the order) was near the small Moroccan town of Boujad . Many of the reformist new orders founded in the 19th century in East and West Africa are subtle branches of the Shadhiliyya tribe.

Reform Movements I

Since the 1990s, the devout Wahhabis have been growing stronger in Senegal, mainly in the cities . They criticize what Sufis have always been accused of: veneration of saints and un-Islamic rituals, i.e. syncretism . After the Wahhabis turned to social issues and made political demands, they gained popularity. Its goal is the slow Islamization of society from below and the conquest of political power. Some of the Islamist organizations founded in the 1970s are now reluctant to criticize the Sufis, even allow a little veneration of saints and respect the marabouts in order to get a reflection of the reputation they enjoy among the masses. The approximation serves this purpose.

Usman Dan Fodio (1754-1817), a religious leader of the Qadiriyya order, achieved the same goal of Islamization by military means from the end of the 18th century . At first he gained influence at the court of the Sultan of Gobir , but by 1790 his community became a threat to ruling interests. In 1804, a Gobi army attacked Usman. He had to flee, his Fulbe cavalry army waged a holy war ( Fulbe Jihad of 1804) against the Hausa kingdoms of today's Nigeria . He conquered the capital of the Sultan of Gobir, where he founded the new city of Sokoto in 1809 . The economic boom of the new caliphate became the "Sokoto model of jihad".

The religious zealots did not pursue active proselytizing in the conquered areas; on the contrary, they often prevented the locals from converting to Islam. Fulbe felt racially superior and because of their religion, which they monopolized as the key to success. They did not give up the exclusivity of Islam until the 1950s.

The Ahmadiyya , who are rejected by most Muslims, proselytize using their own Koran translations into national languages. For example, an Ahmadi worked on the first translation of the Koran into Swahili . In 1953 the Ahmadiyya movement published its own translation of the Koran in Swahili. The translation, which includes the original Arabic text and a detailed commentary, was in some cases violently attacked by orthodox preachers who accused it of mistranslation, while others felt challenged. For example, Abdallah Salih al-Farsi worked on an “orthodox translation” contrary to his principle of not translating holy scriptures. Your commitment is accompanied by charitable and development-oriented services. The only one of the reform movements outside of Africa that did not develop in the Arab region but in India is trying to increase its following in Africa through agitation against Wahhabism , which is offered as the “de-Arabization” of Islam. Some success is achieved with young people and western-minded intellectuals. From the 1920s Ahmadiyya are represented in certain areas of West Africa, such as the area around Lagos , in the south of the Ivory Coast and in the north of Ghana (around Wa ). In South Africa , the “ South Africa Ahmadiyya Court Case ” (1982–1985) achieved international attention.

African folk Islam

The practice of Islam has changed considerably in the course of its spread in Africa. When it comes to the question of how an African Islam was formed, there are two perspectives: an Islamization of Africa, then an Africanization of Islam. A specific popular piety arises from their regionally specific interrelationship, which in principle includes observance of the unifying elements of Islam: The recognition of the universal law ( Shari'a ), which is represented in practice by a clergyman; the creed ( shahada ); the adoption of the rites according to the Islamic lunar calendar ; observance of the categories harām and halāl . This includes rules on slaughtering animals and the prohibition of mutilations, skin scratches and tattoos .

With Bilal , an Ethiopian slave and early follower of Muhammad , the African influence on Islam is revered. His job was to call the believers around the Prophet to prayer, so he is considered the first muezzin . According to tradition, Bilal became the ancestor of African Muslims. The eldest of his seven sons settled in Mali, the chronicle leads his descendants to the rulers of the Mali empire .

The relationship to popular Islam

The relationship between “official” Islam and certain religious practices and beliefs, which are known as popular Islam , is one of tolerance or rejection. Influences from traditional African beliefs are either accepted as adat (tradition) or condemned as bidʿa (heresy). Members of certain Sufi orders, whose founders became known as saints and some of whom lead an ascetic life, move away from the Islamic teaching of the legal scholars ( ulama ). Both groups further graded and condemned as superstition and heresy excesses in popular belief that were spread through sermons by individual amulet dealers, miracle healers and soothsayers. In the Maghreb in particular , Islam was not spread among the people either by legal scholars or Sufi mystics, but only through the emotional cult of saints. The numerous Sufi brotherhoods maintain a strict puritanical or a mystical religion, or a folk cult dominated by spiritual beings, to very different degrees. The Gnawa and the Hamadscha belong to the latter groups, which operate on the fringes of society, especially in Morocco . Music and dance play an essential role in their rituals. The feminine spirit Aisha Qandisha is at the center of the worship of Hamaja .

Reform movements against “pagan” customs and grave cults ( Ziyāra ) were initiated by both Islamic orthodoxy and Sufi sheikhs. In West Africa, Ahmad al-Tidschani , founder of the Tijaniyya , turned against the veneration of saints and at the same time against the political struggle (i.e. against the marabout ). In the east, the Sudanese Mahdi , a sheikh of the Sammaniya order, established a rule of religious intolerance.

What should be called popular Islam compared to the general term “Islam” can only be clarified within the respective cultural framework. Islam came to sub-Saharan Africa primarily without Arabic culture as a legal doctrine and formed a legal framework that was superior to the local community. African culture was linked to Islam as a passive factor in this process. For a Muslim marriage, a bridal gift (gift from the groom to the bride, Sadaq or Mahr ) is required. This rule was built into the African wedding custom, understood as a ritual of passage , and had little influence on it overall. The extent to which practices and beliefs can be assigned to Islam or an earlier tradition is perceived differently within individual cultures. Two neighboring ethnic groups in Darfur should serve as an example: The Islamic Berti differentiate linguistically between āda, "habit" and dīn, "religion"; So they make assignments in individual cases, but can combine both in everyday life without conflict. The consumption of millet beer is not foregone, but daily prayers. The Zaghawa , who are under the influence of the Tijaniyya order, are also practically 100 percent Muslim, but judge their sacrificial cults and rainmaking ceremonies not as “pre-Islamic customs” but as an integral part of their religious tradition.

Individual reasons for converting to Islam

The adoption of Islam, which spread under the first Arab dynasties in North Africa, was probably mostly an avoidance strategy. The Abbasid Caliphate (750–847) already engaged in brisk trade in ivory, precious woods, hides and slaves. The Sharia forbade the enslavement of Muslims. The payment of taxes and the evacuation into slavery could be prevented by converting to Islam. The political and cultural claim to dominance of the Islamic core countries was not dissimilar to that of the later European colonists. The Arabs' contempt for the black population weighed on the relationship between the two as a mortgage. Together with the slave traders, Islam was perceived as hostile and spread rather hesitantly in the landlocked countries along the trade routes. In the north there was a pressure to convert in the cities and generally in Arab-dominated areas and a rather negative attitude towards Islam in the countryside. Peoples living further south and suffering from the scourge of the slave hunters could develop little understanding for the religion of the new masters.

In East Africa, Islam was integrated into the network of trade relations between the Swahili coastal cities and the interior. From the 13th century on, traders and emigrants from the Arab region brought with them not only their language but also the beliefs practiced in their countries of origin at the time, so that there was a continuous process of approximation and renewal of Islam. Newly immigrated Arabs regularly defamed the faith they found as unorthodox. According to the lineages in Arabia, social classes were formed within Swahili society.

By converting to Islam, the African population sought to participate in the success of Arab traders, and this should be linked to a demarcation from the lowest class of unbelievers. However, the desired status ideal was not achievable.

There were other reasons that led to converting to Islam: After a larger Islamic population group had already lived in the cities in the 19th century, carriers of trade caravans also converted to Islam. In the event of fatal accidents far away from home and family, a brother in faith was on hand to ensure a dignified burial. More oriented towards this world: the circumcision, reminiscent of an African initiation rite, made contact with the urban Swahili women easier , since men now belonged to the same culture.

In South Africa the healing ritual Ratiep was imported with the Muslim slaves from the Indonesian islands . This Sufi cult creates a connection to God so that the soul receives strength in compensation for the slave labor of the body. Ratiep is a syncretistic practice that can be derived from an ancient Hindu dance on the island of Bali . With a monotonous chant in the background, a semi-hypnotic sword dance was performed, which could lead to skin injuries. In Cape Town in the 18th and 19th centuries, the ritual was the main reason for converting to Islam. What began as a concession for ordinary slaves fell into disrepute as a pure entertainment value at the end of the 19th century. Today Ratiep is popular among the Muslim working class of the townships in Cape Town .

A new contribution to the Islamic mission at the end of the 19th century was the call to fight against the European colonial rulers. Since the religion could already be considered indigenous, there were massive conversions to Islam in protest at the time of the anti-colonial uprisings. Christianity was considered a religion of oppression. (See below for the opposite situation in Nigeria .)

Africa's influence on Islam

The greatest obstacle to be overcome before accepting Islam is the cosmogonic order of traditional African beliefs, below which people are strictly integrated into a social structure in everyday life. As a whole, it encompasses the dead souls of the deceased up to five generations back. Here the individual takes his place within the order of creation; in Islam he is alone in relation to God. Ancestor worship in Africa is fundamental there and completely alien to Islam. The past, understood as real (influencing) time, comes into Islam as an African substrate, whose believers derive their duties in the present day and from the Koran and Sunna.

In practice, the dogma of the one God and the five precepts of faith were adopted and strictly followed without giving up clan structures and marriage rules. Likewise, cults of possession (cf. Bori ) continue to be carried out by priests. The power of magic is no more doubted by Islam than by Christianity. As syncretism , traditional belief and Islam become equivalent when, among the Muslim Songhai in Niger, obsession cults invoking Hauka spirits have the same effect as the recitation of Islamic verses as an alternative. In northern Nigeria, under the - until recently still moderate - Islam with Songhai and Hausa the importance and effectiveness of mask cults and figural shrines did not decrease. - Nevertheless, most of the Muslims in Nigeria declared that they had the right to convert pagans and emphasized their collective commitment to jihad.

In the Sahel zone , amulets in the form of leather pouches with sewn-in Kor claims are worn around the neck or on the arm. They are designed to protect yourself, your family or your property against witchcraft and all diseases. To make them, a scholar who can write in Arabic and a craftsman who binds the paper in leather are needed. According to popular belief, the hand of Fatima protects against the evil eye . Often envy is seen as the cause of such damaging spells. Modesty is a preventive measure: the children of the wealthy are put in poor clothes or are downgraded by a correspondingly low name (as in Sudan Oschi, “slave”).

The Mganga is responsible for cults of possession and healing in East Africa . He understands his practices as compatible with Islam and speaks at the beginning of the Islamic opening formula Bismillah . If the tasks partially overlap, the Mwalimu ("teacher") is his opponent. As an Islamic scholar, he is an authority who is supposed to impart religious knowledge and above all to protect the community from the threats of un-Islamic deviations. For this he has Baraka .

Another sign of the assimilation power of Islam are the Gnawa, who were dragged north from the Sahel from the 16th century onwards . Black African healing arts arrived in Morocco through the former slaves. Much of the spiritual world evoked with the help of demon mask dances was compatible with Arab folk Islam and resulted in timeless myth in its basic structure.

Sudan II - Tsar Cult and the Role of Women

In contrast to the increasing political radicalization of Sunni Islam, a pronounced popular Islam has been preserved in Sudan, in which the concept of saints and spirits also includes devotion to Mary. Traditional healers, whose recipes are based on the beliefs of Sufism, are accepted in large parts of the Islamic population. They are credible as the descendants of holy men ( Walis ) who show the blessing power ( Baraka ) they have acquired, as it cannot be acquired through their own actions, Allah's work on earth and is passed on from the healers to their descendants. Many healers are sheikhs , which gives them social and political power in addition to their spiritual powers. Sufi healers usually do not oppose Sharia. Although the veneration of saints contradicts Orthodox Islam, there have been few attacks against healers among spiritual leaders, whose authority has been widely recognized by the population. They are currently harassed by fundamentalist groups.

healer

There are two groups of healers in Sudan: The Faki (or Feki ) is a wanderer who travels from village to village selling his religious offerings. He is feared because he can practice black magic ( damage spell ). Women come to him with the request that he work on their dissolute husband or rival second wife. His healing abilities are inferior to those of Faqir . He is a second-rate scholar who lives on alms and sells talismans. As an exorcist, he is called to the sick person's bed. His illusion medicine is occasionally supplemented by the administration of herbal ingredients. Many Faki have performed the Hajj , everyone can read the Koran. They teach children and work at weddings and funerals.

The Faqir organizes activities in mosques and Koran schools and negotiates disputes as a lower authority. His healing methods are also based on animistic customs, magic and Islamic belief. Most faqirs have an effect on the patient, who is only surrounded by a small group of spectators, whereas a respected healer at the beginning of the 20th century was able to transfer his baraka to sick people sitting in the crowd by waving his open hands.

Therapy by Tsar

A special spirit was probably introduced from Ethiopia at the end of the 19th century. The possessive spirit of people appears in the form of a foreigner: an Ethiopian, a Christian black African or a European. In a tsar cult that often lasts for several days, the wishes of the spirit are fulfilled. In return for official recognition, a form of the ritual in Port Sudan was smoothed out in the 1980s by prohibiting alcohol consumption ( see: Merisa ) and drinking sacrificial animal blood, and the loud accompanying music was modernized with the addition of brass.

Most tsar practices are carried out by women and only a few men participating in them. Women do not live under the Islam of men; in conservative, traditional societies, due to the gender segregation, they maintain a parallel Islamic culture, the interpretation of the religious rules of which is the same as that of their men or can differ considerably. The latter applies to Sudan. Conflicts arise between the outer, male world of Orthodox Islam, which barely tolerates Sufi healings, and the popular rituals of the Tsar practitioners, the Sheikhas , whose social status is low. They are mostly older women who are divorced or widowed; Descendants of slave mothers who are ethnically discriminated against because of their darker skin color. Patients are exclusively women, whose obsession manifests itself in psychosomatic complaints and can be explained as an attempt at temporary delimitation. Beliefs marginalized by official Islam are expressed in the cult of underprivileged women in urban fringe areas. The Sheikhas appear as priestesses in a dance ritual, with the participation of which, through offerings and after an admission of guilt, the patients can expect healing. A closed circle with lifelong membership is formed between the Sheikha and her patients. Upper-class women who have parties with tsar dances in urban centers in Sudan and Egypt are paving the way for general social recognition. They hold Tsar-Bori ceremonies with singing, dancing and drum accompaniment. As a public dance and music event, echoes of tsar rituals are known to an international audience. There is also the older and more traditional form of the cult, which is known as tanbura after the lyre in the center .

In the early 1930s, the ethnologist Michel Leiris observed the cult of the Tsar in Ethiopia. He understood the presented ritual as a drama in the sense of a staging, which however is less subject to rational control (not a simulation), but in which the imagined tsar spirit is actually suffered. Leiris recognized a connection between theater and ritual, which does not lead entirely into the other world of the sacred, but at least into an intermediate world that contains the spiritual basis of every ritual: the religious experience.

Cultural conflict with traditional religion

Change of religion can lead to identity conflicts. The first Swahili traders came from the East African coast to the Kingdom of Buganda in the 1840s , whose ruler Mutesa not only accepted the goods of the well-traveled Muslims, but also their faith. Mutesa had a large mosque built and encouraged the Muslims who had settled there to spread Islam. In the late 1860s he referred to himself as a Muslim. He obeyed the Friday prayer, the fasting month of Ramadan, and arranged for an Islamic (new) burial for his ancestors. He quarreled with his clan elders because he refused to be circumcised and gave up eating pork.

In contrast, Osei Bonsu , ruler of the Ashanti kingdom at the beginning of the 18th century, was not a Muslim, but carried an Islamic talisman , cloaks with Arabic inscriptions and the Koran with him. Some Muslims at his court took part in his drinking bouts and the annual sacrificial rituals.

From the 1930s onwards , a new cultural conflict emerged from the Négritude , a movement away from European colonialism and towards pan-African roots, and a spreading, intolerant, Saudi Arabian Islam. The conflict between the black African tradition and the Saudi Arabian form of Islam is one of the causes of civil wars in the Sahel and Sudan . This Islam, which forces you into a completely new way of life, ultimately replaces traditional African society.

Dispute about the true faith

Such a dispute is usually instigated and won by representatives of dogmatism. A prerequisite is an area that has been Islamized for a long time. The fight ( jihad ) is started verbally by denying an area the status of Dār al-Islam .

At the end of the 18th century, Usman dan Fodio took to the field against domestic states in which Islam was practiced along with the traditional Bori cult. Bori religious practices show (still hidden) a close connection with Islam, more precisely, they show how deeply Islam had arrived in society. Some of the spirits lived on under new names in Islam, while Muslims referred to Bori followers positively as “magicians”. The first defeat of this popular Islam was experienced by Usman with the establishment of his caliphate of Sokoto in 1809, the last so far with the introduction of the Sharia in 2000 in northern Nigeria .

After Benin Islam arrived in the north in the 14th-15th Century, in the south in the 18th century. It was introduced by marabout dealers from Mali and Nigeria. Since then, the Islamic leaders have also been spiritual mediators. In Sufi orders, students were instructed in the Koran and trained as marabouts within five to ten years. Since the beginning of the 20th century, in line with a general trend in West Africa, the strictly regulated Tijani order has spread in northern Benin in a variant that emphasizes recitations and mystical elements and establishes centers of teaching ( Zawiya ).

In 1961, King Saud of Saudi Arabia founded an Islamic university in Medina . The aim of this “Citadel of Wahhabism ” is that graduates from all over the world who have been taught in the “right” faith should return to their home countries as missionaries. The first students from Benin had graduated in the 1980s. Since then they have tried to replace the traditional Koran schools in Benin with madrasas with a fundamentalist orientation . The new Islamic elite is marginalized by a lack of job prospects. The clashes between the two opposing camps continue.

Reform Movements II

How did Islam become intolerant in Northern Nigeria? Because of the harsh colonization and slave trade that Fulbe carried out in the 19th century in Hausa areas, the European colonial powers were seen as liberators and Christian missionaries as advocates of the enslaved population. (The former confirmed the Fulani rule to consolidate their own power and the latter fought the Fulbe as competitors.) Islam presented itself in total opposition to local rites and ancestral identity; the rituals could continue to be practiced in Christian villages. In the countryside, the Puritan Islam introduced by Usman Dan Fodio remained the religion of the rulers. This is not contradicted by the Hausa’s attempts to join this religious community for social reasons.

In the 1950s to 1970s Abubakar Gumi (1924–1992, Hausa: Yan Izala ) founded a new dogmatics against the two Sufi orders of the Qadiriyya and Tidschaniya in Nigeria : the right to guidance ( Irschad ) was replaced by detailed rules of practical life for everyone social issues expanded. After independence in the 1960s, Islam was considered part of modernity, and at the same time a state Islamization program was staged by Fulani politicians in order to secure support from their own following. Islam brings a modern national identity, access to power and status is expected. Football games offered by the Islamists since the 1980s make it easier for young people to make a decision for the supporters; these are more attractive than the Dhikr ceremonies of Sufi scholars. In January 2000, Sharia law was introduced in one state, and in 2002 in all twelve northern states.

The Muslims in South Africa are made up of descendants of Indian plantation workers who came to the country in the 19th century, immigrant Africans from Malawi and Zanzibar and converts among the township population since the 1950s . As a progressive counterpart to the traditional community, some Islamic youth organizations were founded in the 1970s. Saudi Arabia gives money and influences. One of the organizations declares the state illegitimate and calls for an election boycott. The common struggle of the Muslims against apartheid shaped a specifically South African form of Islam. Many ANC leaders converted to Islam during the liberation struggle, and since independence the Muslim community has been divided between ethnic origins and fundamentalist ideologies.

Same story - On the role of women

There is no feminine Islamic teaching, instead there are cultural differences in the practice of faith.

Segregation and tradition

The externally visible segregation of the sexes has a pre-Islamic tradition in certain African societies. It does not indicate an Islamic influence, but is a general characteristic of hierarchical class societies, in which social status and prestige are defined by avoidance laws, spatial or symbolic separation and a special sense of honor. The physical separation of women in these cases is based on non-Islamic factors, but is justified by Islamic clergymen with the requirement of ritual segregation. The geographical restriction of women to the domestic area with the compulsion to veil when they leave the house exists in Africa partly in countries north of the Sahara and within the black African countries especially in northern Nigeria and on Zanzibar. In northern Nigeria, the isolation of women, which began in the 15th century and which increased in the 19th century, was sometimes interpreted as anti-colonial resistance, because it meant that tax-collecting colonial administrators could be denied access to the homesteads. The strictest form of seclusion is practiced by women from wealthy upper-class families.

The few women in Africa who wear a niqab can almost only be found in Arab cultures. A frequently expressed idea of the women who wear a covering that covers the whole body and face is that they have an individual space at their disposal, that they are virtually surrounded by the domestic women's area on the street and can thus expand their radius of action. The external environment is declared to be an unclean and dangerous space in which the pre-Islamic Jāhiliyya period still exists. The own position can be increased morally through demarcation.

In contrast, in the patriarchal and practically 100 percent Islamized society of the Afar , who in northeast Ethiopia predominantly practice nomadic grazing, no Islamic dress code could prevail. Afar women wear long brown skirts and cover their chests with a colorful T-shirt or, occasionally, just pearl necklaces.

There were times when women naturally enjoyed an Islamic education as did men. The Sufi scholar (and city patron of Algiers ) Sidi Abdarrahman (around 1384–1469) is said to have taught 1000 pupils in the morning and 1000 pupils in the afternoons in Islamic law and in mysticism. Aside from the exaggerated honor of the saint figure corresponds in practice the traditional Mohammed attitude to education of women and generalizes the example of the rich merchant's daughter Fatima Al-Fihri, who gave her money to 859 the University of al-Qarawiyyin in Fes to establish.

In the Middle Ages, women and men were indiscriminately accepted into many Sufi orders. Only in the Aissaoua order founded by Sidi Muhammad ibn Isa (1465–1523) can it be mentioned as a special feature that it initiates women to the same degree as men in Morocco today. Whereby this order with its ritual practice has moved far away from orthodox Islam: The founder, who became known through various superhuman abilities, brought an order into being whose followers appear as fakirs and fire-eaters.

Counterworld

Women generally have fewer opportunities to develop when participating in the Islamic rite. For Egypt, Trimingham therefore made the general statement that the men were to be found in the mosque on Fridays, while the women were to be found at the saints' tombs. Even if this division is only partially correct, besides the mentioned veneration of saints of Sufism there are certain cults within popular Islam that originate from the animistic tradition and have developed into places of retreat especially for women. These include the cults of possession Tsar in Sudan (mentioned above), Derdeba in Morocco, Stambali in Tunisia, Bori in Nigeria, Pepo in Tanzania or the Hauka spirits of the Songhai . Healers who practice these rituals are usually female, as are those possessed by the spirit and the audience at the events. All cults are not about casting out the spirit , but simply gaining control over it so that it can be used to heal psychological problems. Those affected mostly come from a socially disadvantaged class. This means women who are excluded from participating in the Orthodox Islamic rites, as well as black Africans who are second-class citizens in the Maghreb countries with a Dīwān spirit. Spirit possession is not a symptom of a whole society, but only of a limited circle, but is a factor in general religious awareness.

Orthodox and saints

Usman dan Fodio's missionary jihad led to the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate in the early 19th century . The second Sultan of the Caliphate became Usman's son, Muhammad Bello (ruled 1815–1837) , after some uprisings were put down . The Sharia laws were strictly monitored, the Bori cult of urban women was just tolerated, the old Hausa culture was otherwise destroyed as well as possible. Usman's daughter Nana Asma'u (1793–1864) is mentioned for her role in setting up educational institutions. She developed a pedagogy for women, contributed to the spread of her father's religious reforms, but also considered Bori practices to be suitable for solving everyday problems. Islamic women's organizations founded in Nigeria from the mid-20th century onwards refer to Asma'u: the first women's group was the National Council of Women's Societies formed in the 1950s, followed in 1965 by the Muslim Sisters Organization and, as the most important, the two organizations Women in Nigeria (1982) and Federation of Muslim Women's Association (FOMWAN). In its first declaration in 1985, FOMWAN called for the introduction of Sharia courts, demanded women's rights in the workplace and the rejection of IMF credits.

Numerous examples can be given of influential women in Islam in Africa who have little to do with one another. Ibn Arabi was tutored by two women, the old ascetic Shams Umm al-Fuqara and for several years by Munah Fatima bint Ibn al-Muthanna, who was over 90 years old. In 1951, Mahmud Muhammad Taha proclaimed a political-religious reform concept in Sudan , which was powerfully disseminated not only by the Republican Brothers but also by the parallel organization, the Republican Sisters . In the 1980s, this led to the emergence of socialist feminists in Sudan. Religious women were generally seen as the only common ground and were posthumously worshiped; In many cases, however, it became clear that they were moving in a male domain and had to adjust accordingly.

Women often took on informal roles; as female sheikhs, they seldom assumed leadership roles. A well-known exception is the former slave Mtumwa bint Ali († 1958), who spent her youth in Zanzibar, was accepted into the Qadiriyya order and later became the leading scholar in the central region of Malawi. She initiated men and women into the order. In Senegal, Sokhna Magat Diop inherited the leadership of a branch of the Muridiyya from her father, who died in 1943. Although she was recognized as an authority and continued the order on the traditional path, she rarely appeared. She usually left public speaking to her son.

In legends of Islamic popular belief, there is a natural relationship with holy women. In the Moroccan town of Taghia ( Tadla-Azilal region ), Saint Mulay Bu 'Azza, who died around 1177 at the age of 130, is venerated. He was a simple shepherd from the mountains, had never learned to read or write, traveled around as a dervish and was able to tame dreaded lions. In the legend, Lalla Mimuna, also a saint, became his wife. She couldn't speak Arabic and couldn't even remember the simplest prayer formulas. As a remnant of a pre-Islamic tradition, it is worshiped together with Bu 'Azza, a donkey, a snake and a lion. Every day, many pilgrims come to the grave of the Sufi saint Sidi Abu l-'Abbas es Sabti (1130–1205) in Marrakech , patron of the poor and the blind. Women veiled in black predict the future by pouring lead and using magical tablets written by the saint.

See also

literature

All of Africa

- Thomas Bierschenk and Marion Fischer (eds.): Islam and development in Africa. Mainz Contributions to Africa Research, Volume 16. Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-89645-816-2

- Mervyn Hiskett: The Course of Islam in Africa. Edinburgh University Press, 1994

- Timothy Insoll: The Archeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge World Archeology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge / New York 2003, ISBN 0-521-65171-9

- James Kritzeck and William Hubert Lewis (eds.): Islam in Africa. Van Nostrand-Reinhold Company, New York 1969

- Ioan Myrddin Lewis (Ed.): Islam in Tropical Africa. Oxford University Press, London 1966

- Bradford G. Martin: Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa. African Studies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1976; 2003, ISBN 0-521-53451-8

- Nehemia Levtzion and Randall L. Pouwels: The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press, Athens (Ohio) 2000

- Eva Evers Rosander and David Westerlund (eds.): African Islam and Islam in Africa: Encounters Between Sufis and Islamists. C. Hurst, London 1997. ISBN 1-85065-282-1

- John Spencer Trimingham: The Influence of Islam upon Africa. Longman, London / New York 1968, 2nd edition 1980

West Africa

- Lucy C. Behrmann: Muslim Brotherhoods and Politics in Senegal. Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1970

- Michael Bröning and Holger Weiss (eds.): Political Islam in West Africa. An inventory. African Studies Vol. 30. LIT Verlag, Münster 2006

- Peter B. Clarke: West Africa and Islam: A Study of Religious Development from the 8th to the 20th Century. Edward Arnold, London 1982, ISBN 0-7131-8029-3

- Ernest Gellner : Saints of the Atlas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1969; ACLS History E-Book Project 2006, ISBN 1-59740-463-2

- Uwe Topper : Sufis and saints in the Maghreb. Eugen Diederichs Verlag, Munich 1984; 1991, ISBN 3-424-01023-5

- John Spencer Trimingham: Islam in West Africa. Oxford University Press, London 1959

East Africa

- Ladislav Holy: Religion and Custom in a Muslim Society: The Berti of Sudan. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1991, ISBN 0-521-39485-6

- Ali Salih Karrar: The Sufi Brotherhoods in the Sudan. Chr Hurst & Evanston, Northwestern University Press, London 1992, ISBN 1-85065-111-6

- Abdulaziz Y. Lodhi and David Westerlund: African Islam in Tanzania. Curzon Press, London, New York 1997. Online chapter on the development of Islam in Tanzania since independence in 1961

- John Spencer Trimingham: Islam in East Africa. Oxford University Press, London 1964; Ayer Company Publishers, Manchester 1980, ISBN 0-8369-9270-9

Web links

- Roman Loimeier: Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa. BPB 2003

- Abdurahman Aden: The muezzin awakens the spirits. , ZfK 3/2003

- Islam and Indigenous African Culture. In: Paul Halsall: Internet African History Sourcebook. ( Memento from June 5, 2001 in the Internet Archive )

- Julia Schlösser: Adoration of saints in the northern Egyptian provincial town of Rashid. First results of empirical research. Institute for Ethnology and African Studies No. 52, 2005 (Also general information on the different assessments of the veneration of saints by Islamic legal scholars. PDF file; 212 kB)

- Database Islam in Africa (AfricaBib, African Studies Center, Leiden) Online bibliography with more than 6800 titles, mostly in European languages (in English).

Individual evidence

- ↑ The sum of the country information published in the CIA World Factbook results in 43.4% Muslims and 41.3% Christians, the sum from the country information from the Federal Foreign Office gives 44.2% Muslims and 39.6% Christians, both as of March 2009; Le Monde diplomatique , Atlas der Globalisierung , Paris / Berlin 2009, p. 144 names 45% Muslims and 37% Christians.

- ↑ John Iliffe : History of Africa. CH Beck, Munich 1997, p. 62, also: Werner Ende, Udo Steinbach (ed.): Islam in the present . Munich 1996, p. 445

- ↑ John Iliffe: History of Africa. CH Beck, Munich 1997, p. 66

- ^ Franz Ansprenger: History of Africa. CH Beck, Munich 2002, p. 37

- ↑ Mervyn Hiskett, pp. 99f

- ↑ Mervyn Hiskett, p. 101f / Nehemia Levtzion: Islam in the Bilad al-Sudan to 1800. In: Levtzion and Pouwels, pp. 69-71

- ↑ Ahmed BA Badawy Jamalilye: Penetration of Islam in Eastern Africa. Muscat, Oman 2006 ( Memento from July 19, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 490 kB)

- ↑ Ahmed BA Badawy Jamalilye, pp. 8f

- ^ Edward A. Alpers: East Central Africa. In: Leftzion and Pouwels, p. 315

- ↑ Martin Fitzenreiter: History, Religion and Monuments of the Islamic Period in Northern Sudan. MittSAG, No. 6, April 1997 Part 1: History of Sudan in Islamic times. (PDF file; 1.08 MB)

- ↑ Abdel Salam Sidahmed: Politics and Islam in Contemporary Sudan . Curzon Press, Richmond 1997, pp. 6, 27

- ↑ Werner Ende and Udo Steinbach (eds.): Islam in the present. Munich 1996, pp. 487-495

- ↑ John Edwin Mason: "Some Religion He Must Have." Slaves, Sufism, and Conversion to Islam at the Cape. Southeastern Regional Seminar in African Studies (SERSAS) 1999 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ John Spencer Trimingham, The Influence of Islam upon Africa. P. 53

- ^ John Spencer Trimingham, The Influence of Islam upon Africa. P. 60

- ^ Beat Stauffer: Mysticism as a Means of Fighting Religious Extremism. Sufi Traditions in Northern Africa. Qantara.de 2007

- ↑ Annemarie Schimmel : Mystical Dimensions of Islam. The history of Sufism. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 1995, p. 351

- ↑ Uwe Topper, pp. 44f, 70f, 86

- ↑ Uwe Topper, pp. 55–59, 145, 152

- ^ Adriana Piga: Neo-traditionalist Islamic Associations and the Islamist Press in Contemporary Senegal. In: Thomas Bierschenk, Georg Stauth (Ed.): Islam in Africa. Münster 2002, pp. 43-68

- ↑ Gerard Cornelis van de Bruin Horst: Raise your voices and kill you animals. Islamic Discourses on the Idd el-Hajj and Sacrifices in Tanga (Tanzania). Amsterdam University Press, Leiden 2007, p. 97

- ↑ Eva Evers Rosander and David Westerlund: African Islam and Islam in Africa. Encounters between Sufis and Islamists. Ohio University Press, Athnes 1998, p. 102

- ^ J. Spencer Trimingham: Islam in East Africa. Oxford University Press, London 1964, p. 110

- ↑ Mervyn Hiskett, p 118

- ^ History of Muslims in South Africa. A Chronology ( Memento of March 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ John Spencer Trimingham, pp. 56f

- ^ John Spencer Trimingham, pp. 44f

- ^ Ulrich Rebstock: Islam in Black Africa - Black Muslims in the USA. in: Gernot Rotter (Ed.): The worlds of Islam. Twenty-nine suggestions for understanding the unfamiliar. Frankfurt 1993

- ↑ Michael Singleton: Conversion to Islam in 19th Century Tanzania as Seen by a Native Christian. In: Thomas Bierschenk, Georg Stauth (ed.): Islam in Africa: Münster 2002, pp. 147–166.

- ↑ John Edwin Mason 1999, p. 21f: An eyewitness account of a Ratiep in 1852

- ^ Sindre Bangstadt: Global Flows, Local Appropriations: Facets of Secularization and Re-Islamization Among Contemporary Cape Muslims. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2007, p. 195

- ↑ John S. Mbiti: African Religion and Worldview. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1974

- ^ Wim van Binsbergen: The interpretation of myth in the context of popular islam. ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. analyzes a very simple but transferable case of an origin myth of an Islamic saint in a village in Tunisia.

- ↑ Martin Fitzenreiter: History, Religion and Monuments of the Islamic Period in Northern Sudan. MittSAG, No. 7, September 1997 Part 2: Islam in Sudan. Pp. 43–47 (PDF file; 2.15 MB)

- ↑ See Ahmad Al Safi: Traditional Sudanese Medicine. A primer for health care providers, researchers, and students. 2006

- ↑ Ahmad Al Safi: Traditional Sudanese Medicine. Recognition. sudan-health.com, 2005

- ↑ Afaf Gadh Eldam: Tendency of patients towards medical treatment and traditional healing in Sudan. Diss. University of Oldenburg 2003, pp. 174–178

- ↑ Heba Fatteen Bizzari: The Czar Ceremony. Description of the ceremony with photos.

- ↑ Michel Leiris : La possession et ses aspects théâtraux chez les Ethiopiens de Gondar , précédé de La croyance aux génies zâr en Ethiopie du Nord. 1938, new edition: Editions Le Sycomore, Paris 1980. Leiris had already written about the tsar cult in his travelogue Phantom Africa. Diary of an expedition from Dakar to Djibouti. 1934, new edition: Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1985

- ^ David Robinson: Muslim Societies in African History. Cambridge University Press 2004, pp. 159f

- ↑ Robinson 2004, p. 133

- ^ Thomas Bierschenk: The Social Dynamics of Islam in Benin. In: Galilou Abdoulaye: L'Islam béninois à la croisée des chemins. Histoire, politique et développement. Mainz Contributions to Africa Research Vol. 17, Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, Cologne 2007, pp. 15–19

- ↑ Galilou Abdoulaye: The Graduates of Islamic Universities in Benin. A Modern Elite Seeking Social, Religious and Political Recognition. In: Thomas Bierschenk, Georg Stauth (Ed.): Islam in Africa. Münster 2002, pp. 129–146

- ↑ Ursula Günther, Inga Niehaus: Islam in South Africa: The Muslim's Contribution in the Struggle against Apartheid and the Process of Democratisation. In: Thomas Bierschenk, Georg Stauth (Ed.): Islam in Africa. Munster 2002

- ↑ Sudan Arabic terms according to: Gabriele Boehringer-Abdalla: Frauenkultur im Sudan. Athenäum Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 1987

- ^ John Spencer Trimingham, The Influence of Islam upon Africa. P. 95

- ↑ Katja Wertmann: Guardians of Tradition? Women and Islam in Africa. In: Edmund Weber (Ed.): Journal of Religious Culture No. 41, 2000, p. 3 (PDF file; 70 kB)

- ↑ Salama A. Nageeb: Stretching the Horizon: a gender-based perspective on Everyday Life and Practices in to Islamist Sub-Culture of Sudan. In: Thomas Bierschenk and Georg Staudt (eds.): Islam in Africa. Lit Verlag, Münster, 2002, pp. 17–42

- ↑ Uwe Topper, p. 138

- ^ John Spencer Trimingham, The Influence of Islam upon Africa. P. 46 f

- ↑ Jessica Erdtsieck: Encounters with forces of pepo. Shamanism and healing in East Africa. ( Memento of August 19, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Tanzanet Journal, Vol. 1 (2), 2001, pp. 1-10

- ^ John Spencer Trimingham: The Influence of Islam upon Africa. P. 83

- ^ Roberta Ann Dunbar: Muslim Women in African History. In: Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels: The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press, Athens (Ohio) 2000, pp. 397-417

- ↑ Knut S. Vikor: Sufi Brotherhoods in Africa. In: Nehemia Levtzion and Randall L. Pouwels: The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press, Athens (Ohio) 2000, p. 448

- ↑ Knut S. Vikor: Sufi Brotherhoods in Africa. In: Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels: The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press, Athens (Ohio) 2000, p. 464

- ↑ Lalla Mimuna, like Lalla Aisha and other spirits, is summoned by women in the Gnawa possession ritual Derdeba in Morocco

- ↑ Uwe Topper, pp. 41–44