Ahmadiyya

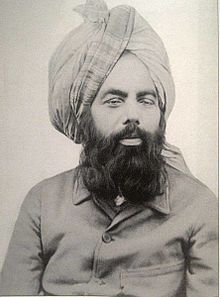

The Ahmadiyya ( Urdu احمدیہ ' Ahmad -tum' ) is an Islamic community founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in British India in the 1880s . From 1889 the followers swore the oath of loyalty to him . In 1901 they entered the official census lists of the British-Indian administration under the name of Ahmadiyya Musalmans .

The religious community, which sees itself as a reform movement of Islam, adheres to the Islamic legal sources - Koran , Sunna and Hadith - whereby the writings and revelations of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad are also of considerable importance. The community sees itself as belonging to Islam. Most other Muslims regard the Ahmadiyya doctrine as heresy and reject it. In Islamic countries, the religious communities and their activities are fought accordingly, which led to restrictions and persecution in these countries.

The community founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad split into two groups after the death of his successor Nuur ud-Din, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat (AMJ) and the Ahmadiyya Andschuman Ischat-i-Islam Lahore (AAIIL), whereby the AMJ which AAIIL has largely supplanted. The current head office of the AMJ is in London (Great Britain), the AAIIL has its international head office in Lahore . The successors of Ghulam Ahmad are referred to by the AMJ as Khalifat ul-Massih (Successors of the Messiah).

Origin and naming

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad came from an aristocratic family of Persian descent. In 1882 he brought out the first two volumes of his main work Barāhīn-i Ahmadiyya ("Proof of Ahmad-tum"), which was initially considered by Muslims to be a work full of strength and originality. Mirza Ghulam Ahmad appeared as an Islamic innovator ( mujaddid ) and in a public announcement at the end of 1888 invited all people “who are seekers of the truth to take the oath of allegiance to him in order to maintain true faith, the true purity of religion and to learn the path of love for God. ”The ceremony of the oath of loyalty then took place on March 23, 1889 in Ludhiana . This event is considered to be the actual founding date of the Ahmadiyya movement.

In December 1891, Ghulam Ahmad announced that his movement would hold annual meetings in Qadian . From this year onwards, Ahmad referred to himself as the Mahdi announced by the Prophet Mohammed and saw himself as the prophesied return of Jesus Christ , Krishna and Buddha in one person. His God-given mission is to unite all religions under the banner of Islam.

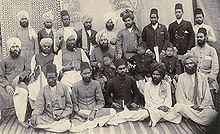

Ghulam Ahmad's followers came mainly from the literary middle class who knew how to understand his complex language. The religious community only officially received its name on the occasion of a census in 1901, when Ahmad recommended his followers to register as "Ahmadiyya Musalmans". Until then they were popularly known as "Qadiani" or "Mirzai".

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad derived the name "Ahmadiyya" from the second name of the Prophet Mohammed , who is referred to as Ahmad in Quran verse 61: 6 by Isa ibn Maryam .

The name Mohammed means "the praised" or "the promised" in Arabic. Mirza Ghulam Ahmad understood this as the work of Mohammed in the Medinan period of prophecy , which he characterized as "triumphant". Ahmad means "the one who praises" or "the one who praises". According to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, this manifested itself in the Meccan period of prophecy , which Mirza Ghulam Ahmad connects with the praise of God.

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad justified the naming by saying that Mohammed stands for glory and sublimity ("Jalali"), while Ahmad emphasizes beauty ("Jamali"). In this way, Ahmad ties in with the early days of Muhammad's proclamation.

The derivation of the term “Ahmadiyya” is controversial: “The Aḥmadīs claim not to derive their name from that of the sect's founder, but from the promise made about him in the Koran.” The term “Qādiyānīya” or “ Mirzaiyya “use; accordingly followers are called "Qādiyānī" or "Mirzai".

cleavage

After Ahmad's death, the doctor and theologian Nuur ud-Din was elected head of the Ahmadiyya movement. With his election on May 27, 1908, the caliphate was established after the promised Messiah .

Criticism soon arose of the caliphate system , which was and is perceived by the opponents as autocratic. After Nuur ud-Din's death in 1914, dissent broke out openly. Above all, the executive body was controlled by " opponents of the caliphate ".

- Around 1,500–2,000 supporters of the caliphate elected Mirza Bashir ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad as the second caliph and thus the new spiritual leader. The committee (Anjuman) is subject to the instructions of the caliph. The group that remained in Qadian was later called the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat (AMJ). The AMJ caliphs are elected for life by an election committee . Since 2003 Mirza Masrur Ahmad has been the spiritual leader of the AMJ as Khalifat ul-Massih V.

- Around 50 Ahmadis - led by Muhammad Ali and Khwaja Kamal ud-Din - refused to follow Mirza Bashir ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad and set up a praesidium in Lahore led by an emir . On the Baiat and spiritual direction should be avoided. The group moving to Lahore later called itself Ahmadiyya Andschuman Ischat-i-Islam Lahore (AAIIL).

Mirza Bashir ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad was able to win over the majority of the supporters, but under the 25-year-old inexperienced leader and without an intellectual, executive and administrative elite, the Qadian group (AMJ) was seriously weakened. The Lahore Group (AAIIL) was also financially stronger and was soon able to open mission stations in Woking and Berlin . Mission stations in Suriname and the Netherlands were added later.

However, Mirza Bashir ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad was able to consolidate the Qadian Group (AMJ) during his tenure and develop it into a powerful organization. As a result, the AMJ was able to gain strong members, while the AAIIL stagnated. The AAIIL is still active today with publications and missionary work, but numerically no longer plays a role and has slipped into insignificance. Since the split, both groups have also been known under the names Qadiani (for AMJ) and Lahori (for AAIIL), especially in India and Pakistan. These terms are used disparagingly by Ahmadiyya opponents.

Teaching

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad saw himself as a prophet, Messiah, Mahdi and the end-time embodiment of Krishna . The teachings of Ahmadiyya are still based on the Koran , the Hadith and the Sunna , but the writings and revelations of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad are of considerable importance. The doctrine of the Ahmadiyya deviates considerably from Orthodox Islam , especially in the position of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the person of Jesus of Nazareth ( Isa ibn Maryam , Yuz Asaf ), the role of the Mahdi, Jihad and in the treatment of apostasy . The Ahmadiyya doctrine is viewed as a wrong path among Orthodox scholars and the followers of this doctrine are regarded as apostates.

Spread history

South asia

Right from the start, the Ahmadiyya strongly focused on expansion in the form of proselytizing. Ghulam Ahmad founded several magazines to spread his teaching, such as al-Hakam in 1897 and al-Badr in Urdu in 1902 and The Review of Religions, the first English-language magazine in 1902 . With this missionary activity, the Ahmadiyya was initially particularly successful in British India . Until the division of the Indian subcontinent, about 74% of the Indian Ahmadiyya communities were in the area of what is now the state of Pakistan. The previous headquarters of the AMJ in Qadian remained in India, which is why it had to leave its center after independence. They left 313 Ahmadis, called Dervishan-e-Qadian, behind to protect their institutions, schools, libraries, printers, the cemetery and other real estate. The main center was temporarily relocated to Lahore. The movement bought a piece of wasteland from the Pakistani government, where they laid the foundation stone for the city of Rabwah on September 20, 1948 . In September 1949 the headquarters were finally moved to Rabwah. Because of the worsening persecution situation in Pakistan, Mirza Tahir Ahmad relocated to London in 1984 .

The literacy of the approximately four million male and female Ahmadis living in Pakistan is around 100%, significantly higher than the national average of 54.9%. The Ahmadis thus make up just under 2% of the total population, but they represent around 20% of the educated population. As a result, many Ahmadis held high positions in the administration and in the armed forces, which, however, aroused the resentment of some groups. Pakistan's first foreign minister and the only Pakistani President of the International Court of Justice , Muhammad Zafrullah Khan , and the only Pakistani and first Muslim Nobel Prize winner in physics to date , Abdus Salam , were members of the Ahmadiyya.

Europe

In the interwar years, both the AAIIL and the AMJ began to set up mission stations in Europe.

United Kingdom

After the English convert Lord Headly had acquired the Shah Jahan mosque in Woking under the leadership of the Indian lawyer Khwaja Kamal ud-Din , Khwaja Kamal ud-Din set up the "Woking Muslim Mission". The mission station was operated by the AAIIL until the 1930s. In addition to the Wilmersdorfer Mosque and the Keizerstraat Mosque , the AAIIL built a mission station in Woking in 1913 and operated the Shah Jahan Mosque there until the 1930s. However, the AAIIL mission stations did not survive World War II.

Only Fateh Muhammad Sayaal, the first foreign missionary to arrive in England in 1913, was able to record a notable success with the construction of the first mosque in London ( Fazl Mosque ) in 1924. The Fazl Mosque in London was inaugurated in 1924 as the first AMJ mosque in Europe . With the Bait ul-Futuh , a mosque with a capacity of 4,500 worshipers was inaugurated in London on October 3, 2003.

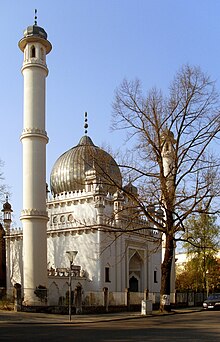

Germany

On October 9, 1924, the AAIIL laid the foundation stone for the Wilmersdorfer Mosque in Berlin . The oldest surviving mosque in Germany was opened on April 26, 1925 and was initially known as the "Berlin Mosque". The Berlin mosque community published the magazine Moslemische Revue from 1924 to 1940 . The Berlin mosque lost its central position during the Second World War and was never able to restore it.

The AMJ was not of great importance in the interwar years. The construction of a mosque on Kaiserdamm near the Witzleben train station had to be canceled for financial reasons.

During the time of National Socialism , the community was unable to keep itself organized and only began to rebuild after the war. Some missionaries returned to India, while the others went to England. The “Islamic Community Berlin” or the “Berlin Mosque” continued to be looked after by German Muslims. Since March 22, 1930, the mosque community has been known as the Deutsch-Muslimische Gesellschaft e. V. An unusual program was connected with this renaming: The new community also accepted Christians and Jews as members, which was unusual for the time. But that is exactly what the community with its mosque on Fehrbelliner Platz did in the time of National Socialism , because the National Socialists saw in the “German Muslim Society e. V. "a" refuge for Kurfürstendamm Jews ". After the death of the Syrian student Muhammad Nafi Tschelebi in the summer of 1933, the German-Muslim Society only led a shadowy existence. As a result, the National Socialists managed to instrumentalize the Islamic community and to abuse the mosque for propaganda appearances with Mohammed Amin al-Husseini . B. on the occasion of the Festival of Sacrifice in 1942. In 1962, the German-Muslim Society was revived by the AAIIL and is now based in the Wilmersdorfer Mosque in Berlin .

In 1939, Sadr ud-Din presented the first German translation of the Koran from the pen of the Ahmadiyya, this translation being interspersed with the teachings of the Ahmadiyya. Since Sadr ud-Din spoke insufficient German, he worked with the convert Hamid Markus, who, however, could not speak Arabic. A number of ambiguities resulted from this compilation. After the war, Mohammed Aman Hobohm worked on a revision that he was never able to complete.

It was not until 1954 that the AMJ published its own translation of the Koran into German, which ultimately largely superseded the translation published by Sadr ud-Din.

After the Second World War , Sheikh Nasir Ahmad founded the AMJ mission centers in German-speaking countries from 1946 to 1962. The Allied occupying power allowed him to travel to Germany from Switzerland . A small Ahmadiyya congregation arose in Hamburg , which was first visited on June 11, 1948 by the missionary SN Ahmad. On April 27, 1949, the NWDR Hamburg broadcast a lecture by SN Ahmad, probably Germany's first radio broadcast on the subject of Islam. Finally, the AMJ received approval for a permanent mission, and on January 20, 1949, missionary Abdul Latif took over the leadership of the first local church in Hamburg. On August 9, 1955, the AMJ founded the Ahmadiyya Movement in the Federal Republic of Germany association in Hamburg . V. In 1969 it moved its headquarters to Frankfurt am Main and has been called Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat in the Federal Republic of Germany since 1988 . V. The first two mosques in post-war history were soon built, the Fazle Omar Mosque in Hamburg (1957) and the Nuur Mosque in Frankfurt am Main (1959).

In the post-war period, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat was the first Muslim community to become active in Germany. The high level of organization and the tight structure within the AMJ initially made it an important discussion partner for church and state institutions. For example in the first contribution to the Christian-Muslim dialogue in 1966 in the Catholic Academy of the Archdiocese of Freiburg in Mannheim, in which only the Ahmadiyya represented Islam.

With the increasing organization of the mostly Turkish guest workers, the AMJ has lost its importance since the late 1970s, especially since it was and is excluded from decision-making processes by the federal government - under pressure from certain Islamic groups.

In 1992 the Bait ul-Shakur was built in Groß-Gerau . With space for around 850 worshipers and 600 m² of prayer area, it is the largest mosque in the community in Germany. The Khadija Mosque was built in Heinersdorf in Berlin . The donations were raised by the Ahmadi women .

In 2002 AMJ bought an industrial site in Frankfurt-Bonames and set up the new German headquarters there. It was given the name Bait us-Sabuh (House of the Very Pure). Haider Ali Zafar has been Germany's head of mission since 1973. Abdullah Uwe Wagishauser is the acting emir.

AMJ is pursuing a “ 100 mosques project ” in Germany . The implementation of this plan is viewed critically by parts of the population and led to the establishment of citizens' initiatives in some places, such as Schlüchtern and Heinersdorf . According to the AMJ, it currently has 30 mosques and 70 prayer centers in Germany.

In April 2013, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat in Hesse was the first Muslim community in Germany to be recognized as a public corporation .

In May 2014 Hamburg also granted the Ahmadiya Muslim Jamaat the status of a public corporation.

Austria

The Austrian anthropologist Rolf Freiherr von Ehrenfels converted to Ahmadiyya after hearing about the construction of the Berlin mosque and organized the “Vienna Muslim Mission” in Austria. However, the mission collapsed in 1938 after Austria was annexed to the German Reich when Rolf von Ehrenfels emigrated to India.

Switzerland

The foundation stone of the Mahmud Mosque was laid on August 25, 1962 by Amatul Hafiz Begum, daughter of the founder Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. It was opened on June 22, 1963 by Sir Muhammad Zafrullah Khan in the presence of the Mayor of Zurich Emil Landolt . The Mahmud Mosque in Zurich is the first mosque in the Swiss Confederation and the headquarters of AMJ Switzerland. The community has about 700 members and its emir is Walid Tariq Tarnutzer.

other European countries

From 1927 the AAIIL attempted to evangelize from Albania in the Balkans by translating into Albanian the journals that had already been published in England and Germany and having them published as individual articles in journals. With the beginning of the communist dictatorship in 1944, their efforts came to an end. There was also little successful missionary work in Hungary and Poland, as well as Spain and Italy.

After the Second World War , the AMJ did missionary work in non-communist Europe. Opened in 1955, the Mobarak Mosque in The Hague was the first mosque in the Netherlands , and the first Dutch converts to Islam in the 1950s and 1960s were also members of the Ahmadiyya. The Nusrat Jehan Mosque near Copenhagen, opened in 1967, was the first mosque in the Nordic countries . In the same year, the AMJ also published the first complete Danish translation of the Koran.

On September 10, 1982, the Basharat Mosque in Pedro Abad was inaugurated by Mirza Tahir Ahmad. This was the first mosque to be built in Spain after the Muslim rule over 500 years ago.

Since 2010 the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat has mission stations all over Europe, with the exception of Greece , Latvia and Slovakia .

Nigeria

During the First World War , the Ahmadiyya was able to gain a foothold in Nigeria . Abd ur-Rahim Nayyar was the first Indian missionary in West Africa and reached Lagos on April 8, 1921. He was supposed to support the Ahmadis and Fante Muslims who lived in Lagos in their educational efforts among West African Muslims. At that time, five Islamic groups were active in Nigeria, on the one hand the “Jamaat” (the largest group), the “Lemomu party”, “Ahl-i Koran of Aroloya” (a weak and shrinking group) and the “followers of Ogunro ”(also a small group) and the Ahmadiyya (the smallest group of all). Nayyar developed relationships with the Jamaat group and the Ahl-i Koran very early on. On June 6, 1921, two days before the Id ul-Fitr , members of the Ahl-i Koran, including their Imam Dabiri, took the baiat on Nayyar. In a telegram to India the number of converts was given as 10,000. In fact, it should have been a quarter of it. The conversion of some followers of the Ahl-i Koran is considered premature and superficial. Some only converted because their previous Imam Dabiri converted and turned away after his death in 1928.

Nayyar's attempt to settle the unrest in the Muslim communities failed. Eventually the dispute between the Jamaat and the Ahmadis escalated. For example, hecklers from the Jamaat disrupted a gathering of Ahmadis with insulting songs and used violence against Ahmadis. Two men were arrested in a later trial. Nayyar still visited Kano and Zaria until he returned to Lagos in September 1922. At the end of that year, Nayyar left West Africa forever.

The Ahmadis in Nigeria asked for a new Indian missionary, whereupon Fazl ur-Rahman Hakim arrived in Nigeria in 1935. Upon his arrival, two groups made themselves recognizable within the Ahmadiyya community: the loyalists ("Loyalists"), who recognized the caliph and thus the missionary, and the autonomous ("independents"), who recognized the founder Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, however believed that each national section should act autonomously and without the caliph. The conflict between the two parties became more and more a conflict between two people. The previous imam should step down for the missionary Hakim. The loyalists argued that as a representative of the caliph he deserved a higher rank. The autonomists did not want to accept this, as an imam could not be removed without further ado. The rift came to a head over the decision on the ownership of the first Ahmadiyya school in Nigeria, in which they were ultimately victorious. At the end of 1939, the international headquarters in Qadian Hakim demanded that every Ahmadi have their baiat renewed. The two groups were still popularly called "Independents" and "Loyalists", officially they were called "Ahmadiyya Movement-in-Islam (Nigeria)" (renamed in 1974 to "Anwar-ul Islam Movement of Nigeria") and "Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya" (later renamed to "Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat Nigeria"). The split remained final, but it was only national in scope. In 1943 Sir Muhammad Zafrullah Khan managed to persuade the autonomous authorities to send a telegram to Qadian. They agreed to renew the baiat on the condition that the loyalists restore all offices, as they did before Hakim's arrival. The compromise proposal was rejected by the headquarters in Qadian. Conciliation talks continued, but were unsuccessful.

Ghana

In March 1921, Abd ur-Rahim Nayyar reached Saltpond , who visited Nigeria after a month. During this short stay in Ghana , however, he was able to convert almost all Fante Muslims to Ahmadiyya who, unlike in Nigeria, did not relapse. The following year, Fazl ur-Rahman Hakim was permanently responsible for the Gold Coast . In 1923 he set up a headquarters in Saltpond and ran a primary school.

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat, active in Ghana under the name "Ahmadiyya Muslim Mission", has been able to increase its influence in Ghana with dynamic and public sermons due to its well-structured organization and is probably the most charismatic Islamic community. In their lectures the missionaries made use of the Koran as well as the Bible and tried to refute the teachings of Christianity . With this way of working, a disproportionate increase in Ahmadis could be determined. In 1939, 100 Ahmadis were known in Wa , while 22,572 people in Ghana declared themselves to be Ahmadiyya in 1948. In the 1960 census, the number of Ahmadis was put at 175,620. This was linked to violent provocations against the Ahmadiyya, especially on the part of the Wala , who gave up their previously tolerant reputation and took a course of confrontation with the Ahmadiyya. The trader Mallam Salih, who was born in Wa , came into contact with the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in the Kumasi region in 1932 and joined the Ahmadiyya in Saltpond a month later. He now preached in the Ashanti region and was able to convert his trading partners and the Ashanti to Ahmadiyya. When he wanted to return to Wa, Orthodox opponents drove him out of the city. His sermons, marked by Reformation zeal, were a thorn in the side of the Sunnis and Tijani . He and his family were not allowed to get water, food or leave his home. From March 23, 1933, Mallam Salih was officially a missionary and visited Ahmadis in Tamale and preached in the villages on the way there. Police protection was necessary on his way back. In Dagbon , the home of the Dagomba , and in Yendi , Salih preached from 1939 to 1940, again looking for the Sunnis and Tijani as target groups. The Tijanis countered the verbal attacks by the Ahmadiyya on the teachings of the Sunnis with physical violence, among other things. For example, the Tijanis persuaded the people of Dagbon to throw stones at children and whistle to Ahmadi preachers. In November 1943, an attack was carried out on an Ahmadiyya mosque on Salih's property.

At the beginning of 1944 the Ahmadis filed a complaint with the Governor of Ghana, Alan Cuthbert Maxwell Burns - after talks, the irritated climate finally improved. The first convert to Ahmadiyya under the Wala Mumuni Koray , who later ruled as King of Wa from 1949 to 1953 , also ensured a moderate mood . Nevertheless, Ahmadis were attacked at major events such as Friday prayers , so that from the 1950s to the 70s they could only take place under police protection. From the 1970s onwards, the Ahmadiyya shifted the focus of its missionary work more and more to Christians, so that the aggressions on the part of the Sunnis and Tijani became less and less.

Right from the start, the Ahmadiyya provided humanitarian aid to Ghana, established hospitals and schools that are accessible to all students and teachers regardless of their religion.

| 1921-1974 | 1974-2000 | |

|---|---|---|

| Preschools | 0 | 102 |

| Elementary schools | 42 | 323 |

| further training | 1 | 6th |

| Hospitals / clinics | 4th | 11 |

| Missionaries | 51 | 128 |

| Communities | 365 | 593 |

| Mosques | 184 | 403 |

The rapid increase in the number of Ahmadiyya social institutions in Ghana was supported on the one hand by Mirza Nasir Ahmads' “Nusrat Jahan Project”, which was supposed to secure financial support for the education and health systems of the Ahmadiyya in Africa. For example , the “Nusrat Jahan Teachers Training College”, named after the project, was set up in Wa in order to ensure the required capacity of teachers. In 1966 a theological school (Jamia Ahmadiyya) was opened to meet the need for missionaries. On the other hand, the efforts are motivated by the idea of achieving a “revival of Islam in Ghana”. So it was said at the opening of the fourth hospital:

"Building hospitals and educational institutions in this country is part of our goal to restore the lost honor of Islam."

The Sunni and Tijani saw the social engagement of the Ahmadiyya as a distortion of Islam in Ghana. As a result of the worldwide agitation against the Ahmadiyya, a 7-point resolution was passed in the National Conference of the Sunnis, which took place from October 9th to 10th, 1970, in which the Ahmadiyya movement was declared a “shame for Islam in Ghana”.

United States

The first acquaintance with the American continent came in 1886 in an exchange of letters between Mirza Ghulam Ahmad and Alexander Russell Webb . At that time, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad was still a respected scholar among Indian Muslims. Alexander Russell Webb later converted to Islam. During his trip through India in 1892 he expressed his wish to visit Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, as he had done him a "great favor" of bringing him closer to Islam. However, Orthodox Muslims prevented him from visiting. The first American Ahmadi is considered to be Mirza Ahmad Anderson, who converted to Ahmadiyya in 1901 after an exchange of letters.

Muhammad Sadiq, who was originally assigned as a missionary for the Woking Mosque , traveled to the USA on January 24, 1920 . On the crossing, his green and gold turban caught the attention of some fellow travelers, so that he began to preach on the teachings of the Ahmadiyya ; He was able to persuade seven fellow travelers to convert to Ahmadiyya. Sadiq arrived in Philadelphia on February 15, 1920 , as the first AMJ missionary to America . He was immediately arrested by the American authorities for preaching a religion that also allows polygamy . Trapped in the Philadelphia Detention House , he continued to preach and gained another 20 followers. He was released after two months on condition that he would not preach on polygamy.

A graduate of the University of London and a professor of Arabic and Hebrew , Muhammad Sadiq began writing articles on Islam - by May 1920, twenty articles had appeared in American magazines and newspapers, including The New York Times . In the fall of 1920 he worked with the editor of the Arab newspaper "Alserat" and founded an association near Detroit. This association, of which Sadiq was elected chairman, was supposed to bring together orthodox and heterodox communities to protect Islam. From July 1921, Muhammad Sadiq began to publish a quarterly magazine called "The Moslem Sunrise" in which the American public was presented a peaceful, progressive and modernized Islam. During the period of the first issue, 500 letters on Islam, along with a copy of The Muslim Sunrise, were sent to Masonic lodges in the United States and some 1,000 Ahmadiyya books were sent to major libraries. Celebrities such as Thomas Edison , Henry Ford, and then President Warren G. Harding also received Ahmadiyya literature.

Sadiq founded the “Chicago Muslim Mission” in 1921 and built the Al-Sadiq Mosque , which was later named after him . He continued to give lectures in schools and lodges on the East Coast and the Midwestern United States, which were well received. In September 1923, Sadiq finished his work in America and returned to India. In 1923, 1925 and 1928 more missionaries followed for the USA. The Ahmadiyya mainly sought out the immigrant Muslims who looked for guidance after their arrival. The Ahmadiyya missionaries were hostile to the American media and criticized society for its racist attitudes. This point found approval among African Americans, so that between 1921 and 1924 there were over 1,000 new entries. Some 40 members of the Universal Negro Improvement Association were also drawn to the Ahmadiyya. By the time the Nation of Islam was founded in the 1930s, the AMJ was able to bring together most of the converts among African Americans. By 1940 the number of converts rose to five to ten thousand.

Chicago served as the national headquarters of the AMJ until 1950. It was then relocated to the American Fazl Mosque in Washington, DC until 1994. The headquarters has always been in Bait ul-Rehman in Silver Spring .

The AAIIL opened its first center in the USA in 1948, but it had to be closed again in 1956 due to a lack of staff.

In the USA, in contrast to Germany, there was a lively community life within the Ahmadis, the vast majority of whom were African-American. The situation changed when entire families from South Asia settled in the United States and, at the same time, African Americans withdrew from the Ahmadiyya movement. The migrants took part in the community life in the mosque, which attracted individual African American people. Cultural differences played a far greater role than religious practice. In a survey, the women said their intercultural understanding was solid, while the American and Pakistani men recognized the need to further develop the understanding between the two ethnic groups.

Canada

The first Ahmadis came to Halifax to study or immigrate in the 1930s , but on rare occasions. The first communities arose when more and more Ahmadis migrated mainly to Ontario in the 1960s . In 1966 the community was registered under the name "Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam, Ontario". On October 17, 1992, in the presence of Mirza Tahir Ahmad and many members of the government, the Bait ul-Islam (House of Islam) was opened on the outskirts of Toronto . Surrounding communities declared October 16 and 17, 1992 to be "Ahmadiyya Mosque Day" and the week from October 16 to 23, 1992 to be "Ahmadiyya Mosque Week". With the Friday Sermon of Mirza Masroor Ahmad was on July 4, 2008 in Calgary , the 15 million CAD expensive Bait un-Nuur (the light house) opened. With an area of 15,000 m² and a prayer area of around 4,500 m², it is the largest mosque in Canada . There is a theological training center for Ahmadiyya missionaries in East Mississauga.

Iraq

In 1921 the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat showed the first attempts to proselytize the Arabian Peninsula. The first Jalsa Salana was held in Baghdad in 1922 and a letter was sent to King Faisal I setting out the teachings of Ahmadiyya . After 1939 no Ahmadiyya activities can be proven.

Syria

Jalal ud-Din Shams was the first missionary to arrive in Damascus . After an attempted murder, he was expelled from the country by French authorities. For the late 1930s, the number of Ahmadis is estimated at around 50 believers. An anti-Ahmadiyya fatwa was published in 1954 , but Mirza Bashir ud-Din Mahmoud Ahmad was able to visit the country the following year. In 1958, Syria confiscated the property of the Ahmadiyya Movement and its activities came to an end.

Israel

The Ahmadiyya efforts in Haifa have been successful. In 1928, after his expulsion from Syria , Jalal ud-Din Shams built a mosque on the Carmel Mountains . Despite resistance, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community was able to establish itself in the area. In the late 1970s, the Mahmud Mosque was built in Kababir, south of Haifa. In 2019, their number is estimated at 1,000 to 2,200 people. The most famous supporter in Israel is the Knesset MP Ayman Odeh

South East Asia

Already in the 1920s the Ahmadiyya was carried to Southeast Asia through missions. Kamal-ud-Din, the leader of the Lahore Ahmadis, toured Malaya , Java and Rangoon for two months in 1921 to promote his community. In July 1925, over 2,000 people gathered at the Victoria Memorial Hall in Singapore to protest the influence of the Ahmadiyya on the Malay region. The Lahore faction gained a foothold in the Dutch East Indies as early as 1924, the Qadian faction followed in 1925 with the arrival of the missionary Maulvi Rehmat Ali in Sumatra . After Indonesia's independence, it was recognized by the Indonesian government on March 13, 1953.

Current worldwide situation

According to the World Christian Encyclopedia, the Ahmadiyya is the world's fastest growing Muslim group, as well as the second largest growing religious group. It is estimated that the Ahmadiyya movement has more than ten million followers worldwide, of which 8,202,000 live in South Asia (as of 2002). The movement itself has recently given the number of its followers in the double-digit million range. For Pakistan, state statistics for 1998 give a share of 0.22%. The Ahmadiyya has boycotted the census since 1974. Independent sources put the number of Ahmadis in Pakistan at around 2–5 million. The AMJ has around 35,000 members in over 220 parishes in Germany, including 300 converts .

Larger congregations of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community exist in Europe, North America and West Africa as well as in Southeast Asia. Although the Ahmadiyya missions abroad were only moderately successful in the western world, they were still the first Muslim community to pose a challenge to Christian missionaries. In addition, the network of the foreign mission was useful for receiving the Ahmadis from Pakistan. Ahmadiyya achieved her greatest successes in missionary work in West and East Africa, where she is also involved in education and social services (building schools and hospitals).

The AAIIL has a community in Berlin-Wilmersdorf with fewer than 20 members (as of 2010). The global membership is given as 30,000. It has a mosque in Europe, the Wilmersdorfer Mosque in Berlin . In England , 250 members are particularly active in the London area.

Over 16,000 mosques worldwide are said to belong to the AMJ. Most are said to be in South Asia and Africa.

persecution

The Ahmadiyya is the most persecuted Muslim community. The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat is rejected by many Muslims as non-Islamic because of its differing doctrines and its followers are religiously disadvantaged or persecuted in some countries. In Pakistan, parties were founded specifically to fight against so-called Qadianism as the main component of their party program; in Saudi Arabia , the prevailing doctrine of the Wahhabis is in stark contrast to the Ahmadiyya doctrine. Supporters of the Ahmadiyya movement have been declared legally non-Muslim and therefore have no legal entitlement to a visa and can therefore not take part in the Hajj .

Afghanistan

Abdul Latif acted as a teacher and advisor in religious matters to Habibullah Khan . After reading something about the Ahmadiyya around 1893, he sent his disciple Abd ur-Rahman to Qadian. When he published the Jihad teachings of the Ahmadiyya in Kabul , he was found guilty of apostasy by Emir Abdur Rahman Khan in 1901 and sentenced to death. Abdul Latif was initially arrested in Kabul in 1903 after his arrival from Qadian. His former student and now the Emir of Afghanistan gave him the opportunity to renounce his belief. Because of the refusal he was found guilty of apostasy and stoned in July 1903 . Under the rule of Amanullah Khan , with the stoning of Nimatullah on August 31, 1924, a wave of persecution broke out in which further Ahmadis were arrested by February 1925. If they left they were released and two of them were sentenced to death. Since then, no active Ahmadis have become known in Afghanistan.

Pakistan

Riots in the 1950s

The "Majlis-i Ahrar-i Islam", which feels part of the Dar ul-Ulum Deoband , was active in India as early as the 1930s, but at that time most anti-Ahmadiyya campaigns were blocked by a ban on the Majlis-i Ahrar -i Islam to be contained by the British government. In the new state, the Ahrar formed anew and on May 1, 1949, publicly demanded for the first time that the Ahmadiyya be declared a non-Muslim minority. Over time, the Ahrar also called for Ahmadi Muhammad Zafrullah Khan to be removed from his post as Foreign Minister of Pakistan and for Ahmadis to be boycotted in the social environment. In addition, the Jamaat-e-Islami put the ruling Muslim league under further pressure with its demand for an Islamic state and also called for the Ahmadiyya to be declared a non-Muslim minority.

In June 1952, the Islamist parties formed an alliance that now increasingly appeared as an extra-parliamentary anti-Ahmadiyya front. The first planned action of this “Majlis-i Amal” alliance was aimed at shop owners; they should keep the Ahmadis out of their shops. The Muslim League announced in July 1952 point to the fundamentalist parties. From their party headquarters in Gujranwala , they first called on July 17, 1952 for the Ahmadiyya to be excluded from the Islamic community. Violent attacks against Ahmadis followed, especially in the west of the Punjab province, in order to induce the province's Muslim League to act. Although the Muslim League looked at the rampage of its own party with reservations, it remained passive. The Pakistani press also supports the Islamist parties by branding Ahmadis as non-Muslims. Ultimately, the Muslim League of Punjab Province gave in and also spoke out in favor of classifying the Ahmadis as non-Muslims. For the first time, a clear tendency was discernible: The Ahmadiyya problem should no longer be viewed from a religious perspective - as the Majlis-i Ahrar and the Jamaat-e-Islami aimed at - but should be clarified under constitutional law.

On January 21, 1953, the Majlis-i Amal Action Front gave Prime Minister Khawaja Nazimuddin the ultimatum to declare the Ahmadiyya a non-Muslim minority within a month and to remove the Foreign Minister. Instead of complying with the demands, however, on February 27 the government arrested major Majlis-i Amal leaders. This gave rise to protests which ended in the hitherto most violent riots, with Ahmadis being attacked, looted and massacred. The government and the military remained neutral in this case and applied martial law for the first time in Pakistan's history.

After the involuntary resignation of the Prime Minister of Punjab Province, calm returned. In April, Prime Minister Khawaja Nazimuddin and his cabinet were also deposed. In the new government, Zafrullah Khan continued to work in the Foreign Ministry.

A month after the riot, a committee of inquiry was tasked with shedding light on the riots in Punjab. The committee's final report severely attacked the leaders of the Islamist parties , known as ulema , stating that they were solely responsible for the unrest. Regarding the requirement of this ulema, the report said:

"If we adopt the definition given by any one of the ulama, we remain Muslims according to the view of that alim but kafirs according to the definition of every one else."

After this setback in the fight against the Ahmadiyya, things remained relatively quiet for the next 20 years, especially since Muhammad Ayub Khan managed to put a stop to the fundamentalist parties.

Resumption of the smoldering conflict in the 1970s

Disappointed by the defeat in the Bangladesh war , the Islamist parties and interest groups demanded that the Islamic position in Pakistan be consolidated. Leaders of the Islamist parties raised the Ahmadiyya question again in 1973 and asked, among other things. a. the Saudi Arabian King Faisal ibn Abd al-Aziz to intervene directly with the government of Pakistan. At the Islamic summit in Lahore in February 1974 , he demanded that Bhutto clarify the Ahmadiyya question as quickly as possible and promised to support Pakistan financially in its economic development.

In a fatwa, the Islamic World League declared the Ahmadiyya movement to be heresy in April 1974 and its followers to be non-Muslims or apostates .

Impressed by King Faisal's speech, the religious groups formed the “Majlis Tahaffuz Khatam-i Nabuwat” (MTKN for short) in April 1974 - comparable to the Majlis-i Amal formed in 1953. The MTKN was able to successfully win over conservative students. On May 22nd, a group of these students made a stop at Rabwah Railway Station on their study trip to Peshawar . The students attacked, insulted and molested Ahmadi women. The students continued their journey and announced a repetition of the scenario on the return journey. When they stopped again at Rabwah Railway Station on May 29, about 400-500 Ahmadi students attacked the train and attacked the students. 17 students were slightly injured, but were able to continue their journey. In doing so, the Ahmadiyya committed the serious mistake expected by the MTKN. Shortly afterwards, the Pakistani press published falsified reports of the Rabwah incident and the MTKN used these to intensify the conflict. The atmosphere was similar to that of the 1953 incidents. Violent unrest broke out again in Punjab Province, killing 42 people, including 27 Ahmadis. Bhutto came under increasing pressure, but on June 13, 1974, he made a categorical declaration in the National Assembly in which he held the radical parties solely responsible for the incident in Rabwah. A week later, Bhutto met with his cabinet, which spoke out in favor of finally settling the Ahmadiyya question in the National Assembly.

The third caliphate ul-Massih Mirza Nasir Ahmad and four other Ahmadi scholars faced the National Assembly's special committee in an eleven-day investigation. All allegations against the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community were answered by the five scholars. However, the constitutional amendment of September 7, 1974, which declared the Ahmadiyya to be a non-Muslim minority, could not be prevented. Formally, they were put on a par with Jews, Christians, Buddhists, Sikhs and Hindus, in practice it led to the legitimation of violence against Ahmadis, their mosques were desecrated or burned down. This meant that the Ahmadis were dropped by Bhutto's government after they had been loyal election workers to his party in 1970. The “excommunication” of the Ahmadis by parliamentary resolution is unique in Islamic history and is viewed by many intellectuals as a worrying precedent. The Sunni scholars saw the constitutional amendment and the associated discrimination against the Ahmadis as a further reason to intensify the fight against the heresy of the Ahmadis. In Punjab and the Northwestern Frontier Province in particular , Ahmadis were attacked and murdered or their shops and houses were set on fire, while the government did not intervene and imposed censorship on top of that. As such massacres were repeated, many Ahmadi Muslims sought exile. The most popular receiving countries included England, Canada, the USA and Germany.

Development in the 1980s under the leadership of Zia ul-Haq and creation of Ordinance XX

After Zia ul-Haq took power through a military coup and had Bhutto executed, he publicly declared that he wanted to establish a new "Islamic order" in Pakistan. This spoke again to the fundamentalists for whom the constitutional amendment of 1974 did not go far enough. Zia ul-Haq attacked the Islamic tax system in his Islamization process in 1980. The government issued guidelines for the payment of the Islamic tax, in which non-Muslim minorities, which now legally also belonged to the Ahmadiyya, were denied the right to pay the zakat . The Ahmadiyya, on the other hand, assured that they would continue to pay the zakat.

On April 9, 1984, the MTKN submitted a catalog of demands to the government in which they demanded the following:

- Dismissal of all Ahmadis from key positions

- Arrest of Mirza Tahir Ahmad , the fourth caliph of the AMJ

- Enforcement of the Islamic order in Pakistan

- Identification of Ahmadis as non-Muslims on ID cards and passports

Under Zia-ul-Haq , Ordinance XX was passed on April 26, 1984, which added two paragraphs to the Pakistani Criminal Code (298-B and 298-C). Accordingly, Ahmadis' use of Islamic eulogies , the adhān call to prayer , the salām and the bismillah as well as the designation of their prayer houses as a “mosque” were punishable by imprisonment of up to three years with an additional fine. Signs with the inscription “Mosque” were removed from their mosques and the corresponding lettering was painted over. Furthermore, any acts that could offend the "religious feelings" of a Muslim, as well as any missionary activities are prohibited. The public life of the Ahmadiyya community was severely restricted or made impossible.

One day after the ordinance was passed, the MTKN met and thanked Zia ul-Haq and reminded him of the remaining demands. Ahmadis have been murdered by fanatics and destroyed in Jhang and Multan Ahmadiyya mosques. Although some parties are protesting against Ordinance XX, voices were dominant that celebrated the ordinance as a great service for Islam. The Ahmadiyya Caliph urged the Ahmadis in Pakistan to continue to behave peacefully and to pray for a solution to the problem.

As early as March 1984, the US embassy informed the Ahmadiyya headquarters in Rabwah that the Pakistani government would take the first steps against the Ahmadiyya as soon as possible. After Ordinance XX was passed, the Caliph met with his closest advisers. They said that he should leave Pakistan immediately. Indeed, Mirza Tahir Ahmad found herself in a precarious position because any Islamic act would have meant up to three years in prison. Since a caliphate ul-Massih is elected for life, this would in turn have resulted in a headless congregation. Until the day of departure on April 30th, Zia ul-Haq commissioned five secret services to monitor the city of Rabwah, but they made contradicting reports about the caliph's whereabouts. When word got around that the caliph had left Rabwah, Zia ul-Haq imposed a travel ban on the caliph at all border posts, seaports and airports. However, Zia ul-Haq made the mistake of imposing the travel ban on his predecessor and half-brother Mirza Nasir Ahmad , who had died two years earlier . Mirza Tahir Ahmad was able to pass through passport control without any obstacles and fly from Jinnah International Airport Karachi to Amsterdam and then on to London. He remained in exile in London until his death in April 2003.

In January 1985, from London, the caliph called on the Ahmadis in Pakistan to remain peaceful and to boycott the February election. However, the elections were in favor of Zia ul-Haq, who was able to pursue his policy of Islamization with a strong mandate. Under pressure from the MTKN, the Punjab provincial government removed the Shahāda letters from Ahmadiyya mosques. At times, the Ahmadis provoked their arrest by wearing the Shahada openly on their bodies, in order to demonstrate the futility of the criminal law in their eyes. Over a thousand Ahmadis have been sentenced to several years in prison for this offense.

On October 12, 1986, insulting the Prophet Mohammed was made a death penalty under Section 295-C. Since the Islamists understood the uttering of the creed of an Ahmadi in itself as a vilification of the prophet, they wanted to deprive the Ahmadiyya of any possibility to continue to designate themselves as Muslims. The Ahmadiyya community in India asked Amnesty International and India's Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi for assistance. Both responded that they were unable to provide aid to the Ahmadiyya as it was a domestic political issue for Pakistan. Later on, Christians and other non-Muslims were also prosecuted under the law.

| Charge | Processes (1984-2005) |

|---|---|

| Representing the Shahada | 756 |

| Calling out Adhān | 37 |

| Pretended to be a Muslim | 404 |

| Use of Islamic eulogies | 161 |

| Performing the obligatory prayers | 93 |

| preaching | 602 |

| Distributing a comment against Ordinance XX | 27 |

| Violation of blasphemy laws (e.g. 295-C) | 229 |

| Other violations | 1,156 |

Further tightening despite the democratization phase under Benazir Bhutto

During the democratization phase under Benazir Bhutto, Ahmadis drew hope that she would abolish the anti-Ahmadiyya legislation. Benazir Bhutto announced:

“Qadianis have been declared non-Muslims under my father's rule. How could I undo the greatest service my father did for Islam? My government will not grant the Qadianis any concession. They remain non-Muslims. "

Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif passed a blasphemy law in 1993 , after which the death penalty can also be imposed. Because of these difficulties, Mirza Tahir Ahmad, the fourth caliphate ul-Massih, left Pakistan and immigrated to London.

The Pakistani Supreme Court on July 3, 1993 dismissed eight appeals by Ahmadis who had been detained under Ordinance XX and Section 295-C. The court justified the decision on the one hand with the fact that the Ahmadis' religious practice was peaceful, but angered and offended the Sunni majority in Pakistan, and on the other hand non-Muslims were not allowed to use Islamic expressions, as they would otherwise “violate copyright law”.

The International Labor Organization criticized the introduction of personal documents in which the founder of the Ahmadiyya must first be declared a “liar” and “cheat” in order to be considered a Muslim. To make matters worse, such a declaration must be signed at every authority and when a bank account is opened. In addition, the specialized agency of the United Nations noted that since Ordinance XX, Ahmadis have been increasingly exposed to discrimination in the workplace and in schools.

Ongoing Persecution in the 21st Century

In an attack on two Ahmadiyya mosques in Lahore on May 28, 2010, 86 Ahmadis were killed during Friday prayers. Pakistani Taliban militias confessed to the attacks.

In October 2017, a court in Sharaqpur Sharif, Punjab Province, sentenced three Ahmadis to death under the blasphemy law. They were accused of posting several banners with "offensive" content on their mosque in the village of Bhoaywal near Sharaqpur Sharif.

Escape abroad

Because of the lynching in Pakistan, Ahmadis sought exile abroad, the network of the foreign mission being useful for receiving the Ahmadis. The single-family house in Berlin behind the airfield of Tegel Airport , used as a meeting center and mosque, was the most important center of the Ahmadiyya in exile, along with the Nuur Mosque in Frankfurt. The Berlin assembly center played a major role in exile politics, as the GDR airport Berlin-Schönefeld was the first port of call for a large number of Ahmadis from Pakistan, not only for Germany, but also for other Western European countries. Until the end of the 1980s, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees rejected asylum applications from Ahmadis from Pakistan, which, however, were occasionally overturned by the decisions of the administrative courts. From the beginning of the 1990s, the Federal Republic of Germany allowed asylum applications to be approved more easily, which led to the rapid growth of the Ahmadiyya community in Germany. Young men were preferably sent to Germany, primarily to secure financial means for the remaining family. The Ahmadis took advantage of the fact that they were distributed as asylum seekers across Germany. They use every stay in a place for a mission, which led to life in the diaspora becoming a religious task before involuntary migration took place.

The European Court of Justice ruled in September 2012 that Pakistani Ahmadis who seek asylum in Germany and plead their religious persecution could not be expected to return to Pakistan and not identify themselves as Ahmadi there. Because the right of asylum protects not only against encroachments on the practice of religion in the private sphere, but also the "freedom to live this belief publicly."

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh , the former East Pakistan, the same Orthodox groups are active as in Pakistan. The most serious incidents occurred in January and October 1999, when one attack and one bomb attack on Ahmadiyya mosques each killed seven Ahmadis. On December 12, 2003, supporters of the anti-Ahmadiyya front demonstrated on Bait ul-Mokarram and demanded that the Ahmadiyya be declared non-Muslim. The Ministry of the Interior banned Ahmadiyya records in early 2004, which raised serious concerns among human rights organizations. The US also reminded the Bengali government that its actions were incompatible with the constitutional freedom of religion. The Ahmadiyya, with the support of several human rights organizations, filed a lawsuit with the High Court, which ultimately overturned the government decision.

Indonesia

The Majelis Ulama Indonesia (MUI) issued a fatwa in 1980, which Ahmadiyya expelled as "un-Islamic, deviant and misleading". The Ministry of Religious Affairs issued a circular in 1984 instructing its regional offices to treat Ahmadiyya as a heresy. With a new fatwa in 2005, the MUI made clear its need to ban the activities of Ahmadiyya in Indonesia. Since then, attacks on facilities of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, which are ultimately justified by this fatwa, have increased. In the same year, the police had to evacuate participants from Jalsa Salana . Since the beginning of June 2008 the Ahmadiyya has been prohibited from any activity in Indonesia by a government decree.

Between 2007 and 2010, 342 attacks on Ahmadis were recorded, the last time on February 6, 2011 in a village in Banten province , where around 1,500 radical Muslims broke into an Ahmadiyya building and executed Ahmadis in front of the police.

Germany

The expulsion of the Ahmadis from the world community of Muslims by the Pakistani parliament in 1974 also had an impact on the Ahmadis living in Europe. From Great Britain , various Pakistani Islamic organizations act against them under the name “ Pasban Khatme Nabuwwat ” (Keeper of the Seal of Prophetism ). Pakistani fundamentalists not only put a bounty on Salman Rushdie , but also the equivalent of $ 250,000 for the person who kills Mirza Tahir Ahmad, 4th Caliphate ul-Masih, who lives in London. The appeal for murder was also printed in a Pakistani newspaper that appears in London. This terrorist organization of Pakistani extremists aims to fight and kill Ahmadis. This organization first became known in 1998, when there were religiously motivated attacks on Ahmadis in Baden-Württemberg and North Rhine-Westphalia. On August 16, 1998, the "Pakistani Welfare Association Mannheim e. V. ”together with the association“ Unity of Islam e. V. ”from Offenbach held a Khatme Nabuwwat conference in the rooms of the Mannheim Yavuz Sultan Selim Mosque . In their statements, the supporters of the “Khatme Nabuwwat” are said to have directed not only against the Ahmadis, but also against the Federal Republic of Germany, as it grants protection to the Ahmadiyya.

literature

- Self-expression of the Ahmadiyya

- Maha Dabbous, Hadayatullah Hübsch : Are Ahmadis Muslims? An answer to the article "Qadianis - a non-Muslim minority in Pakistan" . Verlag der Islam, Frankfurt 1987, ISBN 3-921458-65-X ( online [PDF; 85 kB ]).

- Masud Ahmad, Hadayatullah Hübsch: Jesus did not die on the cross. Three lectures . Verlag der Islam, Frankfurt 1992, ISBN 3-921458-81-1 .

- Muhammad Zafrullah Khan : Principles of Islamic Culture . 4th edition. Verlag der Islam, Frankfurt 2005, ISBN 3-921458-49-8 .

- Muhammad Zafrullah Khan: The Woman in Islam . 3. Edition. Verlag der Islam, Frankfurt 1997, ISBN 3-921458-03-X .

- Mirza Ghulam Ahmad : The Philosophy of the Teachings of Islam . 4th edition. Verlag der Islam, Frankfurt 2008, ISBN 978-3-921458-97-6 .

- Bashir A. Rafiq: The Truth About Ahmadiyyat . Verlag der Islam, Frankfurt 1992. ISBN 3-921458-59-3

- Manfred Backhausen (ed.): The Lahore Ahmadiyya movement in Europe . Ahmadiyya Anjuman Lahore Publications, Wembley 2008, ISBN 978-1-906109-05-9 ( The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement in Europe ).

- Ahmadiyya statements on current issues

- Abdullah Wagishauser (Ed.): Rushdie's Satanic Verses. Islamic statements on the provocations of Salman Rushdie and the appeal for murder by radical Iranian Shiites . Verlag der Islam, Frankfurt 1992, ISBN 3-921458-80-3 ( ahmadiyya.de ( Memento of February 9, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF; 114 kB ]).

- Hadayatullah Hübsch: Fanatical warriors in the name of Allah. The roots of Islamist terror . Hugendubel / Diederichs, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-7205-2296-2 .

- Haider Ali Zafar (ed.): Faith and reason from an Islamic perspective. Answer to the Regensburg lecture by Pope Benedict XVI . Verlag der Islam, Frankfurt 2007, ISBN 978-3-932244-87-2 .

- Mirza Tahir Ahmad : Islam - Answers to the Questions of Our Time . Verlag der Islam, Frankfurt 2008, ISBN 978-3-932244-31-5 .

- Historical representations

- Lucien Bouvat : Les Ahmadiyya de Qadian . Paris 1928.

- Yohanan Friedmann: Prophecy Continuous. Aspects of Ahmadi Religious Thought and Its Medieval Background . 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, New Delhi 2003, ISBN 0-19-566252-0 .

- Antonio Gualtieri: The Ahmadis. Community, Gender, and Politics in a Muslim Society . Mcgill-Queen's University Press, Montreal 2004, ISBN 0-7735-2738-9 .

- Iqbal Singh Sevea: The Ahmadiyya Print Jihad in South and Southeast Asia. In: R. Michael Feener, Terenjit Sevea: Islamic Connections. Muslim Societies in South and Southeast Asia. Singapore 2009, pp. 134-148.

- Simon Ross Valentine: Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama'at. History, Belief, Practice . Columbia University Press, New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-231-70094-8 .

- Criticism of Ahmadiyya

- Hiltrud Schröter : Ahmadiyya Movement of Islam . Hänsel-Hohenhausen, Frankfurt 2002, ISBN 3-8267-1206-4 .

- Mohammed A. Hussein: The Qadjanism. Destructive Movements . League of the Islamic World, Mecca 1990.

- persecution

- Manfred Backhausen, Inayat Gill: The victims are to blame! Abuse of power in Pakistan . 2nd Edition. Akropolis-Verlag, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-929528-08-8 .

- Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat Germany (ed.): Persecution of Ahmadi Muslims. 2006 Annual Review. Special Reports on the Persecution of Ahmadis in Indonesia, Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia and Sri Lanka . 2006 ( ahmadiyya.de ( Memento from January 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF; 3.3 MB ]).

Web links

- Official website of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat (AMJ) Germany.

- Official website of the Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha'at-e-Islam Lahore (AAIIL)

- Evangelical Information Center - Ahmadiyya Movement.

- German translation of the Koran by the Ahmadiyya community.

Remarks

- ↑ The mosque in Bait ul-Futuh holds 4,500 worshipers, the building with all rooms that can be used for prayer almost 10,000 visitors.

- ↑ The Koran. Arabic-German. Translation, introduction and explanation by Maulana Sadr ud-Din ; Verlag der Moslemische Revue (self-print), Berlin 1939; 3rd unchanged edition 2006, The Berlin Mosque and Mission of the Ahmadiyya Movement to Spread Islam (Lahore) (PDF; 597 kB), p. 27.

- ↑ Mirza Baschir ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad (ed.): Koran. The Holy Quran. Islam International Publications, 1954; last: Mirza Masrur Ahmad : Koran the holy Quran; Arabic and German. 8th, revised paperback edition, Verlag Der Islam, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-921458-00-6 .

- ↑ Most recently during Mirza Masrur Ahmad's visit to Africa in 2008 (taken from Friday's address on May 9, 2008)

- ↑ 1950 renamed "The Muslim Sunrise"

- ↑ 19 major religions with 48 groups were examined. The adjusted birth and convert rate was taken into account. The Ahmadiyya comes to a growth rate of 3.25. Only the African American religions are (collectively) higher with a growth rate of 3.3.

- ↑ Population by religion. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012 ; Retrieved August 25, 2012 . It should be noted that in Pakistan religious affiliation is recorded in personal papers. Because membership of the Ahmadiyya in Pakistan has many disadvantages, many Ahmadiyya supporters deny their membership to state authorities.

Individual evidence

- ^ Dietrich Reetz (ed.): Islam in Europe: Religious life today. A portrait of selected Islamic groups and institutions . Waxmann, Münster 2010, p. 95 .

- ↑ Fundamantalism in Islam: The Ahmadiyya Movement: Between Muslim Missionary Sect and Leader Cult . (PDF; 80 kB)

- ^ Juan Eduardo Campo: Encyclopedia of Islam . In: Encyclopedia of world religions . Facts On File, New York 2009, pp. 24 .

- ↑ Cynthia Salvadori: Through open doors. a view of Asian cultures in Kenya . Kenway Publications, Nairobi 1989, pp. 213 .

- ↑ James Thayer Addison et al. a .: The Harvard Theological Review . Volume XXII. Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1929, pp. 2 .

- ^ Howard Arnold Walter: The Ahmadiya movement . Oxford University Press, New Delhi 1991, pp. 15th f . (First edition: 1918).

- ↑ a b Cf. Friedmann 1989, 5.

- ^ A b Simon Ross Valentine: Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama'at. History, Belief, Practice . Columbia University Press, New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-231-70094-8 , pp. 34 f .

- ^ Howard Arnold Walter: The Ahmadiya movement . Oxford University Press, New Delhi 1991, pp. 16 (first edition: 1918).

- ↑ Richard C. Martin (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World . tape 1 . Macmillan Reference USA, New York 2004, pp. 30 .

- ↑ Annemarie Schimmel (Ed.): Der Islam III. Popular piety, Islamic culture, contemporary trends . tape 25 , no. 3 . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1990, p. 417 .

- ^ Spencer Lavan: The Ahmadiyah Movement. Past and Present . Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar 1976, p. 43 .

- ^ A short sketch of the Ahmadiyya Movement . In: Mission scientifique du Maroc (ed.): Revue du monde musulman . tape 1 , no. 1 . La Mission scientifique du Maroc, Paris 1906, p. 544 .

- ↑ a b RE Enthoven: Census of India 1901. Bombay. Part I. Report . tape IX . Government Central Press, Bombay 1902, pp. 69 .

- ↑ Monika and Udo Tworuschka: Religions of the World. Basics, development and importance in the present . Bertelsmann Lexikon, Munich 1991, p. 248 .

- ^ Howard Arnold Walter: The Ahmadiya movement . Oxford University Press, New Delhi 1991, pp. 111 (first edition: 1918).

- ↑ Sahih Bukhari Volume 6, Book 60, Number 419

- ^ Muhammad , Encyclopædia Britannica Online, accessed March 23, 2014.

- ^ Y. Haddad, Jane I. Smith: Mission to America. Five Islamic sectarian communities in North America . University Press of Florida, Gainesville 1993, pp. 53 .

- ^ Lewis Bevan Jones: The people of the mosque. An introduction to the study of Islam with special reference to India . 3. Edition. Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta 1959, pp. 218 .

- ^ A short sketch of the Ahmadiyya Movement . In: Mission scientifique du Maroc (ed.): Revue du monde musulman . tape 1 , no. 1 . La Mission scientifique du Maroc, Paris 1906, p. 545 .

- ↑ Steffen Rink: Celebrating Religions . Diagonal-Verlag, Marburg 1997, p. 137 .

- ↑ a b Khálid Durán, Munir D. Ahmed: Pakistan . In: Werner Ende, Udo Steinbach (ed.): Islam in the present . 5th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-53447-3 , p. 355 .

- ↑ a b Encyclopædia Britannica 2002 Deluxe Edition CD-ROM, Ahmadiyah

- ↑ The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement in Europe, pp. 270f.

- ↑ Werner Ende (ed.): Islam in the present . 5th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, p. 730 f .

- ^ Yohanan Friedmann: Prophecy Continuous. Aspects of Ahmadi Religious Thought and Its Medieval Background . 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, New Delhi 2003, pp. 21 .

- ^ Howard Arnold Walter: The Ahmadiya movement . Oxford University Press, New Delhi 1991, pp. 113 (first edition: 1918).

- ↑ Simon Ross Valentine: Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama'at. History, Belief, Practice . Columbia University Press, New York 2008, pp. 56 .

- ^ Johanna Pink: New religious communities in Egypt. Minorities in the field of tension between freedom of belief, public order and Islam . In: Culture, Law and Politics in Muslim Societies . tape 2 . Ergon, Würzburg 2003, p. 41 .

- ↑ Werner Ende (ed.): Islam in the present . 5th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, p. 731 f .

- ↑ Annemarie Schimmel (Ed.): Der Islam III. Popular piety, Islamic culture, contemporary trends . tape 25 , no. 3 . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1990, p. 419 .

- ↑ See Friedmann 11.

- ^ Mian Muhammad Sadullah: The Partition of the Punjab 1947. A compilation of official documents . National Documentation Center, Lahore 1983, pp. 428 .

- ↑ Simon Ross Valentine: Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama'at. History, Belief, Practice . Columbia University Press, New York 2008, pp. viii .

- ^ Yohanan Friedmann: Prophecy Continuous. Aspects of Ahmadi Religious Thought and Its Medieval Background . 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, New Delhi 2003, pp. 38 .

- ↑ a b Betsy Udink: Allah & Eva. Islam and women . CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 143 .

- ^ The World Factbook: Pakistan

- ^ Amjad Mahmood Khan: Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan. An analysis under international law and international relations . In: Harvard Human Rights Journal . tape 16 . Harvard Law School, Cambridge 2003, p. 243 .

- ↑ Nathalie Clayer and Eric Germain (eds.): Islam in inter-war Europe . Columbia University Press, New York 2008, pp. 27 .

- ↑ Monika and Udo Tworuschka: Religions of the World. Basics, development and importance in the present . Bertelsmann Lexikon, Munich 1991, p. 237 .

- ^ David Westerlund and Ingvar Svanberg: Islam outside the Arab world . St. Martin's Press, New York 1999, pp. 359 .

- ↑ Christopher TR Hewer: Understanding Islam. The first ten steps . scm press, London 2006, pp. 190 .

- ^ Jorgen S Nielsen: Towards a European Islam . St. Martin's Press, New York 1999, pp. 5 .

- ↑ Simon Ross Valentine: Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama'at. History, Belief, Practice . Columbia University Press, New York 2008, pp. 71 .

- ↑ Bernd Bauknecht: Muslims in Germany from 1920 to 1945 . In: Religious Studies . tape 3 . Teiresias Verlag, Cologne 2001, p. 61 f .

- ^ Marfa Heimbach: The development of the Islamic community in Germany since 1961 . In: Islamic Studies . tape 242 . Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 2001, p. 50 f .

- ^ Ina Wunn: Muslim groups in Germany . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2007, p. 159 .

- ↑ Nathalie Clayer and Eric Germain (eds.): Islam in inter-war Europe . Columbia University Press, New York 2008, pp. 103 .

- ↑ Muhammad S. Abdullah: History of Islam in Germany . In: Islam and the Western World . tape 5 . Verlag Styria, Graz 1981, p. 28 .

- ↑ Steffen Rink: Celebrating Religions . Diagonal-Verlag, Marburg 1997, p. 138 .

- ↑ Bernd Bauknecht: Muslims in Germany from 1920 to 1945 . In: Religious Studies . tape 3 . Teiresias Verlag, Cologne 2001, p. 72 .

- ↑ Brandenburgisches Landeshauptarchiv Potsdam, Pr. Br. Rep. 30 Berlin C Tit. 148B, No. 1350.

- ^ Gerhard Höpp: Muslims under the swastika. (PDF) p. 2 , archived from the original on August 14, 2007 ; Retrieved March 10, 2009 .

- ↑ Bernd Bauknecht: Muslims in Germany from 1920 to 1945 . In: Religious Studies . tape 3 . Teiresias Verlag, Cologne 2001, p. 114 f .

- ^ Marfa Heimbach: The development of the Islamic community in Germany since 1961 . In: Islamic Studies . tape 242 . Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 2001, p. 37 .

- ^ Marfa Heimbach: The development of the Islamic community in Germany since 1961 . In: Islamic Studies . tape 242 . Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 2001, p. 38 .

- ↑ Thomas Lemmen: Muslims in Germany. a challenge for church and society . In: Writings of the Center for European Integration Research . tape 46 . Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2001, p. 30 .

- ^ Ina Wunn: Muslim groups in Germany . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2007, p. 156 .

- ↑ Muhammad S. Abdullah: History of Islam in Germany . In: Islam and the Western World . tape 5 . Verlag Styria, Graz 1981, p. 52 .

- ^ Marfa Heimbach: The development of the Islamic community in Germany since 1961 . Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 2001, p. 41 f .

- ↑ Muhammad S. Abdullah: History of Islam in Germany . In: Islam and the Western World . tape 5 . Verlag Styria, Graz 1981, p. 53 .

- ^ Dietrich Reetz (ed.): Islam in Europe: Religious life today. A portrait of selected Islamic groups and institutions . Waxmann, Münster 2010, p. 103 .

- ^ Dietrich Reetz (ed.): Islam in Europe: Religious life today. A portrait of selected Islamic groups and institutions . Waxmann, Münster 2010, p. 104 f .

- ^ Ina Wunn: Muslim groups in Germany . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2007, p. 164 .

- ^ Christine Brunn: Mosque-building conflicts in Germany. A spatial-semantic analysis based on the theory of the production of space by Henri Lefebvre . Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin, Berlin 2006, p. 52 .

- ↑ Freia Peters: Islam now officially belongs to Germany. welt.de, June 13, 2013, accessed on June 13, 2013 .

- ↑ /hamburg/eimsbuettel/article128464078/Muslimische-Ahmadiyyas- wird-Kirchen-gleich-ektiven.html Muslim Ahmadiyyas are given equal status to churches

- ↑ Nathalie Clayer and Eric Germain (eds.): Islam in inter-war Europe . Columbia University Press, New York 2008, pp. 99 .

- ↑ Nathalie Clayer and Eric Germain (eds.): Islam in inter-war Europe . Columbia University Press, New York 2008, pp. 100 .

- ↑ Marc Gaborieau: De l'Arabie à l'Himalaya: chemins croisés. in homage to Marc Gaborieau . Maisonneuve & Larose, Paris 2004, p. 214 .

- ↑ Marc Gaborieau: De l'Arabie à l'Himalaya: chemins croisés. in homage to Marc Gaborieau . Maisonneuve & Larose, Paris 2004, p. 226 .

- ↑ Nathalie Clayer and Eric Germain (eds.): Islam in inter-war Europe . Columbia University Press, New York 2008, pp. 29 .

- ↑ Tomas Gerholm, Yngve Georg Lithman: The New Islamic presence in Western Europe . Mansell Publishing, London 1988, pp. 2 .

- ^ Shireen T. Hunter: Islam, Europe's second religion. The new social, cultural, and political landscape . Praeger Publishers, Westport 2002, pp. 99 .

- ^ David Westerlund, Ingvar Svanberg: Islam outside the Arab world . St. Martin's Press, New York 1999, pp. 392 .

- ^ David Westerlund, Ingvar Svanberg: Islam outside the Arab world . St. Martin's Press, New York 1999, pp. 393 .

- ^ Y. Haddad, Jane I. Smith: Mission to America. Five Islamic sectarian communities in North America . University Press of Florida, Gainesville 1993, pp. 49 .

- ^ Dietrich Reetz (ed.): Islam in Europe: Religious life today. A portrait of selected Islamic groups and institutions . Waxmann, Münster 2010, p. 99 .

- ↑ Kenneth Kirkwood et al. a .: African Affairs Number One . Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale 1961, pp. 61 .

- ↑ Humphrey J. Fisher: Ahmadiyyah. A study in contemporary Islam on the West African coast . Oxford University Press, London 1963, pp. 98 f .

- ↑ Humphrey J. Fisher: Ahmadiyyah. A study in contemporary Islam on the West African coast . Oxford University Press, London 1963, pp. 100 .

- ↑ Kenneth Kirkwood et al. a .: African Affairs Number One . Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale 1961, pp. 69 .

- ↑ Humphrey J. Fisher: Ahmadiyyah. A study in contemporary Islam on the West African coast . Oxford University Press, London 1963, pp. 103 f .

- ↑ Kenneth Kirkwood et al. a .: African Affairs Number One . Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale 1961, pp. 73 .

- ↑ Humphrey J. Fisher: Ahmadiyyah. A study in contemporary Islam on the West African coast . Oxford University Press, London 1963, pp. 109 .

- ↑ Humphrey J. Fisher: Ahmadiyyah. A study in contemporary Islam on the West African coast . Oxford University Press, London 1963, pp. 110 f .

- ↑ Kenneth Kirkwood et al. a .: African Affairs Number One . Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale 1961, pp. 82 .

- ↑ Humphrey J. Fisher: Ahmadiyyah. A study in contemporary Islam on the West African coast . Oxford University Press, London 1963, pp. 112 f .

- ↑ Kenneth Kirkwood et al. a .: African Affairs Number One . Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale 1961, pp. 84 .

- ↑ Humphrey J. Fisher: Ahmadiyyah. A study in contemporary Islam on the West African coast . Oxford University Press, London 1963, pp. 118 . 118

- ^ CK Graham: The history of education in Ghana from the earliest times to the declaration of independence . Cass, London 1971, p. 151 .

- ↑ Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, p. 87 .

- ↑ Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, p. 89 .

- ^ Ivor Wilks: Wa and the Wala. Islam and polity in northwestern Ghana . In: African studies series . tape 63 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, pp. 183 .

- ^ J. Spencer Trimingham: Islam in West Africa . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1959, pp. 231 .

- ↑ Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, p. 59 .

- ↑ Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, p. 91 f .

- ↑ a b Humphrey J. Fisher: Ahmadiyyah. A study in contemporary Islam on the West African coast . Oxford University Press, London 1963, pp. 120 .

- ^ Ivor Wilks: Wa and the Wala. Islam and polity in northwestern Ghana . In: African studies series . tape 63 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, pp. 180 .

- ↑ Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, p. 96 .

- ^ Ivor Wilks: Wa and the Wala. Islam and polity in northwestern Ghana . In: African studies series . tape 63 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, pp. 184 .

- ^ Ivor Wilks: Wa and the Wala. Islam and polity in northwestern Ghana . In: African studies series . tape 63 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, pp. 177 f .

- ↑ Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, p. 196 f .

- ↑ Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, p. 245 .

- ↑ Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, p. 182 .

- ↑ a b Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-8258-8991-2 , p. 169 .

- ↑ Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, p. 308 f .

- ↑ Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, p. 170 .

- ↑ Nathan Samwini: The Muslim resurgence in Ghana since 1950. Its effects upon Muslims and Muslim-Christian relations . In: Christianity and Islam in Dialogue . tape 7 . LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, p. 194 .

- ^ Edward E. Curtis IV: Muslims in America. A short history . Oxford University Press, New York 2009, pp. 26 .

- ↑ Umar F. Abd-Allah: A Muslim in Victorian America. The Life of Alexander Russell Webb . Oxford University Press, New York 2006, pp. 61 .

- ↑ Umar F. Abd-Allah: A Muslim in Victorian America. The Life of Alexander Russell Webb . Oxford University Press, New York 2006, pp. 124 .

- ↑ Umar F. Abd-Allah: A Muslim in Victorian America. The Life of Alexander Russell Webb . Oxford University Press, New York 2006, pp. 63 .

- ↑ a b Stephen D. Glazier: Encyclopedia of African and African-American religions . Routledge, New York 2001, ISBN 0-415-92245-3 , pp. 24 .

- ^ Richard Brent Turner: Islam in the African-American Experience . 2nd Edition. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1997, pp. 114-115 .

- ↑ Aminah Mohammad-Arif: Salaam America. South Asian Muslims in New York . Anthem Press, London 2002, pp. 29 .

- ^ Richard Brent Turner: Islam in the African-American Experience . 2nd Edition. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1997, pp. 116 .

- ↑ a b c Aminah Mohammad-Arif: Salaam America. South Asian Muslims in New York . Anthem Press, London 2002, ISBN 1-84331-009-0 , pp. 30 .

- ^ Richard Brent Turner: Islam in the African-American Experience . 2nd Edition. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1997, pp. 118 .

- ^ Y. Haddad, Jane I. Smith: Mission to America. Five Islamic sectarian communities in North America . University Press of Florida, Gainesville 1993, pp. 60 .

- ^ Richard Brent Turner: Islam in the African-American Experience . 2nd Edition. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1997, pp. 120-121 .

- ^ Yohanan Friedmann: Prophecy Continuous. Aspects of Ahmadi Religious Thought and Its Medieval Background . 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, New Delhi 2003, pp. 30-31 .

- ^ Richard Brent Turner: Islam in the African-American Experience . 2nd Edition. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1997, pp. 121 .

- ^ Richard Brent Turner: Islam in the African-American Experience . 2nd Edition. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1997, pp. 125 .

- ^ Richard Brent Turner: Islam in the African-American Experience . 2nd Edition. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1997, pp. 130 .

- ^ Richard Brent Turner: Islam in the African-American Experience . 2nd Edition. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1997, pp. 127-128 .

- ^ Y. Haddad, Jane I. Smith: Mission to America. Five Islamic sectarian communities in North America . University Press of Florida, Gainesville 1993, pp. 62 .

- ↑ Jane I. Smith: Islam in America . Columbia University Press, New York 1999, pp. 74 .

- ↑ Aminah Mohammad-Arif: Salaam America. South Asian Muslims in New York . Anthem Press, London 2002, pp. 156 .