Swahili city-states

The Swahili city-states are a number of cosmopolitan cities on the East African coast that became considerably wealthy through intensive trade in gold and ivory from the Zambezi Plateau and experienced their rise and prosperity in the period from the ninth to the early 16th centuries. Although each of these cities represented an independent political unit, they shared the common language Swahili , Islam as a defining cultural element and similar social and cultural structures, which were reflected, for example, in the architecture of the cities. They combined elements of African, Arab and other societies and formed their own culture.

Many of these cities, such as Mogadishu , Sofala and Kilwa Kisiwani , developed into important trading centers that traded on the one hand with Inner Africa, on the other hand with Arabia and the coasts of Asia and sometimes even minted their own coins .

Geography of the coast

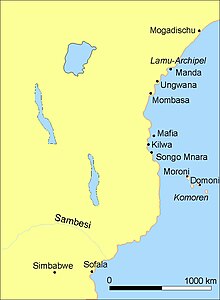

The coast of East Africa, from Somalia in the north to Kilwa in the south, is about 1500 kilometers long. It formed the core area of the Swahili cities. In the northern part they were mostly not on the mainland, but on islands near the coast, as the mainland here is very dry and hardly offered any suitable bays for a harbor. South of the Lamu Archipelago, the climate is more humid and therefore friendlier, so that the actual coast was also used from here. Directly opposite the archipelago is the mouth of the Tana , in front of it are the islands of Lamu, Pate and Manda. Major cities lay on each of these islands, if not at the same time. Here and further south there are numerous coastal waters and many small bays that are suitable for a harbor. In addition, the fertility of the soil seems to have played a role in the choice of the location of a city, which apparently ensured a certain level of self-sufficiency. A number of important places could thus arise on the mainland, on the other hand you can also find some cities here on offshore islands. To the south of the important city of Kilwa, traders and places are also attested, but there are hardly any water points by the sea and inland there is only desert - these regions were therefore unsuitable for the establishment of ports. The southernmost ports were Sofala , probably more of a transshipment point than a city, in what is now Mozambique and Chibuene . The places are more than 1000 km south of Kilwa. The pottery found there, however, is similar to that of Kilwa. Other cities can be found on the Comoros, about 250 km off the coast of Kenya, and even on Madagascar , which at that time did not play an important role.

Apart from the village settlements in the coastal region, with which these cities were in contact and which they probably also ruled in part, their culture did not penetrate further into inner Africa and was restricted to a narrow zone by the sea.

swell

These city-states were known to the Arabs from the start and have been part of the Islamic world since the 11th century. They have been mentioned many times in various travel reports. A first report came from Al-Mas'udi , who visited the area in 916. Another detailed description of the area was provided by the world traveler Ibn Battuta , who came to Kilwa on the east coast of Africa in 1331. Later important sources are the reports of the Portuguese who arrived here in the early 16th century, sacked some cities and then took over the trade.

The history of individual places can only rarely be deduced from written sources, although some chronicles have survived ( Kilwachronik , Patechronik ). The coins bearing the names of the ruling sultans are another historical source.

The Archeology provides an important contribution to the history of the region. The first excavations began in 1948 James Kirkman , who explored Gedi within ten years . In the following years, other places were investigated, the buildings and mosques of which are often still fully preserved. Neville Chittick , in particular , dug in places like Kilwa and Manda in the 1960s. Many of these ruined cities are popular tourist destinations today.

history

Until the 10th century

The east coast of Africa was already described by the Romans in the Periplus Maris Erythraei in the first century AD. For a long time, however, there was no archaeological evidence for this period. In ancient sources this region is referred to as Azania and a trading post called Rhapta is mentioned several times .

Only research in recent years has been able to provide evidence on site. Accordingly, there were permanent settlements on the coast from the birth of Christ. These are characterized by the Kwale ceramic and iron slag. In Kivinja numerous imports from the Middle East and the Mediterranean could be found and prove archaeologically the writing traditional trade. Finds of Iranian ceramics from later times also inland 50 km behind the coast of Bagamoyo show that trade in the Indian Ocean was already connected to a regional trade network during this period.

In the eighth century the Arab region was plagued by civil war . Many people fled their homeland and some of them went to East Africa, where they met the Zanj , who controlled small market towns on the coast. Although the Zanj apparently offered fierce resistance, in the long run the newcomers mixed with the indigenous population. The earliest proven location to date is on Manda Island in the Lamu Archipelago. Islamic-Persian ceramics and Chinese porcelain were found here during excavations. Remnants of a wall have also been found showing that this site, which dates back to the 9th century, was fortified. Many places on the east coast, although most of them are much smaller (no more than 5 hectares on average), produced comparable excavation results. Islam does not seem to have had any significance as a religion, so far only a mosque has been found in Shanga and there are a few burials that are classified as Islamic because of their orientation. There is an Arabic inscription from Kilwa, which at least proves that someone in this place was able to speak this script and language. The ceramics from the Middle East show that there was already international trade back then. This ceramic usually accounts for 1–5% of the total ceramic material in the finds.

Another reason for the boom in trade in this region may have to do with the relocation of the Islamic capital to Baghdad . The Persian Gulf and with it the Indian Ocean thus gained greater importance in the Islamic world.

11-16 century

In the 11th or 12th century new settlers from Arabia may have arrived. The real heyday of the region begins. The cities grew considerably, others such as Lamu , Baraawe and Mogadishu were only now being founded. On average, it is assumed that the existing settlements will be enlarged four times, most of which have now acquired an urban character. During this period, Islam was adopted as a religion in all places . As a result, numerous mosques were built.

Excavations in many places brought to light Chinese porcelain and other imported goods. The percentage of these imports in found goods is, however, overall hardly higher than before. Since the places were now larger, an increase in the volume of trade can be assumed in any case. Kilwa in the south seems to have achieved a special supremacy during this period. It is also one of the few places from which a chronicle ( Kilwachronik ) has been preserved and whose history can therefore be roughly traced. The names of about twelve sultans are known through coins.

Most of the stone buildings were erected between the 12th and 15th centuries. From the few written sources it appears that some cities like Kilwa tried to establish supremacy over the others, but apparently never really succeeded. Not even when the Portuguese arrived they were able to unite against this enemy. Shortly before the arrival of the Portuguese there were signs of crisis. Iron and textile production in particular slowly declined.

Al-Hasan ibn Sulaiman Abu'l-Mawahib (around 1330), who was certainly the most important ruler of Kilwa, described himself as the victorious king on his coins , which suggests a certain striving for hegemony. Finally, there is also evidence that the sultans waged campaigns in inner Africa, but there never seems to have been constant conquests. It is mostly spoken of a jihad against pagans. On the whole, however, relations with Inner Africa seem to have been rather good. The residents of the inland z. B. in the attack of the Portuguese on Kilwa military aid and sent mainly archers to help.

The arrival of the Portuguese

Even before the first Europeans arrived, there were signs of crises. Kilwa experienced a decline as early as the 15th century. Coin production there even stopped in 1375. Perhaps this had something to do with power shifts within Africa. The Munhumutapa empire disintegrated during this time, so that the gold supply was no longer fully guaranteed. Sofala, who was previously dependent on Kilwa, also seems to have made itself independent.

When the Portuguese arrived in this region around 1500, they tried without delay to gain control of the rich cities. In 1498 Vasco da Gama made a pact with Malindi . In the following years the Portuguese drove into the ports with heavily armed ships and demanded that the rulers there declare themselves subjects of the Portuguese. If this requirement was not met, they ransacked the city. The campaign was justified as a holy Christian war . Since even the big cities were not used to having to defend themselves and were also inferior in terms of weapons, the Portuguese had an easy game. In 1503, Ruy Lourenço Ravasco attacked Zanzibar and forced the city to pay tribute. In 1505, Sofala was taken and a Portuguese fortress was built there. Francisco de Almeida looted Kilwa, Mombasa and Baraawe in the following years . The Portuguese now brought the trade under their control, with their main interest being the spice trade with India.

Although most of the cities were not abandoned and there were other mosques and other buildings, the region lost its importance. The heyday of the East African cities came to an end at the beginning of the 16th century.

society

For a long time it was assumed in research that these cities were a high culture, the development of which was initiated by emigrants from Arabia. This view has been put into perspective by Africa research over the past thirty years. Today, the coastal culture of this time is mostly understood as an African society, which received its special character from the diverse contacts with communities bordering the Indian Ocean on the one hand and with groups from the African hinterland on the other.

The cities were influenced differently by the neighboring societies inland, which explains the different dialects of Swahili . The cities of the northern coast in what is now Somalia and Kenya maintained close contacts with Kushite-speaking pastoral peoples, with whom they were also linked through political ties. In the southern cities, Bantu-speaking farmers were the main communication and trading partners on the mainland.

On the other hand, the cities cultivated lively relationships with one another, which the easily navigable ocean - unlike on the impassable mainland - made possible over thousands of miles. They not only exchanged goods, but also people, ideas and technologies. This transport route led to a similar culture and a common understanding of identity developing in the cities.

Islam was one of the most important connecting elements, a second the common language Swahili. Nevertheless, there was no self-designation as a Swahili society . Although there was no common political unity until the arrival of the Portuguese, the cities were less demarcated from one another than from the black non-Muslim population of the hinterland and from the Arab immigrants from overseas.

Social structure of the city-states

The majority of the population living in the cities consisted of black Africans, as the historian Ibn Battuta reported. The Arab comers from the 9th century mixed with the local population and were absorbed in it. The upper class saw themselves as part of the Arab world and traced their origins back to it, but the language on the coast was Swahili and not Arabic, even if at least the upper class knew the Arabic language and script. The ruling families liked to trace their origins back to important places in Arabia . Al-Hasan bin Talut , the founder of the Mahdali dynasty in Kilwa, claimed that his family came from Yemen and that their origins can be traced back to the Prophet himself. To what extent this corresponds to the truth cannot be said. Noble families like to emphasize a better origin in order to underpin their claim to leadership. This information should therefore be treated with some skepticism.

This upper class consisted largely of merchants, which also included the sultan and his family. The sultan imposed high tariffs on goods, which was part of his wealth. The upper class lived in the stone houses that were in the centers of the cities. These people, who called themselves Waungwana , dominated life in the places. Another self-designation of the upper social group was Shirazi , which should indicate their origin from Persia. In fact, these were probably families of African origin who explained their lack of knowledge of Arabic, but who did not want to be identified with non-Muslim and destitute Africans. Only this class owned land and the merchant ships. Above all, the land ownership gave these people access to valuable wood, which was also often exported. Even the hunt for elephants, rhinos or lions was only allowed to them. Exceptions had to be confirmed by the king and his council.

The majority of the population, however, consisted of dependents from this upper class. They were farmers, fishermen and artisans, but also seamen who lived in the cities or in villages on the coast. Three terms have been handed down for this group, suggesting that there was also a social differentiation among them: Wazalia were descendants of released slaves or free descendants of slaves, Watumwa were the slaves and Wageni were visitors or newcomers.

For some of the cities, a network of smaller localities in the area could be proven, which were apparently ruled by the cities and which in turn supplied the cities with agricultural products. Every city had a certain area. Kilwa is known to rule various other places.

Aside from the direct dependence on nearby localities, the culture of the city-states must have been very attractive to more distant societies. There were among the Shona in present-day Zimbabwe, with whom the Swahili had lively trade contacts, several hundred Muslims in the 16th century and Islamic traditions were cultivated into the 20th century.

economy

Although most cities got rich from overseas trade, they were also part of a local economic system that allowed them to be self-sufficient. Hardly any of them were able to support themselves, even though they were often in fertile areas. In their vicinity there are small villages that supplied them with agricultural products, with cereals, rice, coconuts, domestic animals and fish being attested. These smaller places in turn are likely to have had close contact with the African hinterland. Sea shells were found up to 150 km inland.

Fishing as a source of food played a special role. The fish were probably hunted with spears. Accordingly, there are mainly slower fish. There is evidence of extensive local pottery, pearl and iron production. Ceramic production in particular followed the ceramic tradition of Africa almost entirely and underpins the independent African character of this cultural landscape. The ceramics seem to have been produced locally in the individual households at first, later it was transferred to special workshops. The find of the spindle whorl is evidence of its own textile production. The structure and processing of iron played a special role. Iron was processed for its own needs, but also exported in large quantities. Excavated iron objects show a wide range of well-known metalworking techniques, such as hot or cold forming . There was steel produced.

The main export items in overseas trade are primarily raw materials such as ivory, chlorite , turtle shell and gold, which was probably imported mainly from the Munhumutapa empire . In return, these places received high-quality metal goods, glass and porcelain, perhaps also fabrics, oils and spices from the Near and Far East. It is uncertain whether slaves, which gained enormous importance as export goods in the 19th century, were also traded. In Iraq, slave revolts in the 9th century were attributed to the "Zanj", black Africans, including those known as "Kanbula", which in turn probably refers to the island of Kanbula in the Lamu archipelago. Ibn Battuta also wrote about the Sultan of Kilwa's frequent raids "into the land of the Zanj".

The trade and traffic at sea was mainly determined by the monsoon winds . The northeast monsoon begins in November and lasts until shortly after January. At this time, shipping on the dhow was dangerous, but the winds offered good opportunities for rapid progress. They used the monsoons for faster seafaring and at the same time tried to avoid their dangerous times. The southwest monsoon begins in April and lasts until July.

Mogadishu is closest to Asia and was therefore the first port to call at. He therefore played an important role. The ships stayed there until the weather was suitable and then continued south. Kilwa, the southernmost city, also seems to have been the southernmost place that one could reach and leave again without having to hibernate. Sofala, in the very south, was apparently only approached from Kilwa.

City structure and architecture

In the eighth and ninth centuries, the villages were mostly small, barely an acre on average. The buildings were usually made of perishable materials such as clay, wood and straw.

A noticeable upswing began in the tenth century. The more important places increased in size, but were still comparatively modest with 10 to 15 hectares . The places can be divided into five classes according to their size. The smallest places, of which there were about 34, were only about an acre. Some of them had a mosque and a few monumental tombs. The next class, of which there were about 39 locations, was no larger than 2.5 hectares. There were one or two mosques, up to ten monumental tombs, and a few residential buildings made of coral stone. The next class was made up of small, 2.5 to 5 hectare cities, of which about 19 are known. They in turn had 1 or 2 mosques, up to ten stone houses, city walls and a few tombs. The penultimate class were cities that were 5 to 15 hectares in size. They had two mosques and 50 to 100 stone houses. Nine cities were included. The largest cities ( Mogadishu , Baraawe , Malindi , Lamu , Mombasa , Pate , Ungwana , Gedi ) occupy an area of at least 15 hectares, there were at least three mosques, various cemeteries and more than 100 stone houses. Kilwa and Mahilaka with an area of approx. 30 and 60 hectares respectively belonged to the largest cities. A population of around 4000 people is attested to around 1500 in Kilwa and its surroundings. The city walls often only surrounded an inner district, while outside there were other significant, non-walled residential areas.

Mosques

There has been at least one mosque in the center of almost every city since the 12th century . Building material was usually coral stone . As a rule, it was a simple room of 9.5 by 5.8 (in Sima) up to 14 by 7.5 meters (in Shanga) in size. This space could in turn be divided by rows of columns. The roofs were made of mangrove wood or had the shape of a dome. Opposite the entrance was the mihrab . It was oriented towards Mecca . It was mostly a simple niche with a pointed arch. These arches were often decorated with geometric designs. Minarets are rare and are more likely to be occupied in the north. There are also few minbars (the pulpit where a preacher spoke). In the few cases where they are occupied, it was an installation made of simple masonry. Wooden minbars are even rarer. The buildings show regional characteristics. In the north, the mosques are divided in the middle by a series of square pillars. In the south, on the other hand, the interior is characterized by two rows of octagonal columns.

Other buildings

In addition to one or more mosques, there were a number of stone houses in which the local upper class lived. Some of these could be very luxuriously equipped with bathing facilities. The entrances were made up of monumental arched doors, which probably once contained wooden doors. These then led to an inner courtyard, which had a raised bench on three sides, on which one could sit. Here the host received visitors and business was done. An elongated reception room followed, which was followed by the private rooms. Large houses also had a courtyard specially reserved for women. Carpets and silk fabrics are documented as room furnishings. In some houses, the representation rooms had walls decorated with rows of niches (zidaka). Export items such as Chinese porcelain were displayed in the niches.

The Portuguese described three-story houses, balconies and numerous gardens in the city for Kilwa: The beautiful houses, terraces and minarets with the palm trees and trees in the gardens made the city [Kilwa] look so beautiful from our ships .

The Sultan's palace usually didn't look much different, even if it was larger. The only exception was the Husuni Kubwa (Swahili: large, fortified house , the name may not be contemporary) called the palace of the Sultan of Kilwa, which was located 1.5 km outside of the city and exceeded all other buildings in the region in dimensions. At that time it was the largest stone building south of the Sahara . The palace consisted of a series of courtyards, had a large octagonal water basin in the private area of the complex, which was certainly used as a bath, a large audience courtyard with benches that was illuminated with lamps at night and numerous chambers that were once vaulted.

There were also large warehouses in every city for the goods to be shipped. In Kilwa these were partly attached to the palace. The vast majority of the population lived in simpler houses made of perishable material. These buildings are difficult to prove today. Within the urban area there were usually several wells for drinking water supply.

In some cities there were elaborate grave monuments within the residential areas, these being decorated with a column in the middle. This is a design typical only for the East African coast. Sometimes these mausoleums bore dated inscriptions.

This architecture is mostly kept rather simple in style. Building ornamentation does occur, but is the exception and is limited to door frames or individual moldings. There are geometric patterns borrowed from Mameluke Egypt. The design of the domes took over Seljuk forms of the 12th century. The pointed arches in mosques, on the other hand, had their origin in India .

See also

literature

- Philip Curtin, Steven Feierman, Leonhard Thompson, Jan Vansina: African History. From Earliest Times to Independence. 2. revised Edition. London / New York 1995, ISBN 0-582-05071-5 .

- Peter Garlake: Africa and its Kingdoms . Koch, Berlin / Darmstadt / Vienna 1975, DNB 1013704363 , pp. 81-93.

- Chapurukha M. Kusimba: The Rise and Fall of Swahili States . Oxford 1999, ISBN 0-7619-9051-8 .

- Derek Nurse, Thomas Spear: Reconstructing The History and Language of an African Society, 800-1500. Philadelphia 1985, ISBN 0-8122-7928-X .

- Kevin Shillington: History of Africa . 2nd Edition. New York 2005, ISBN 0-333-59957-8 , pp. 120-135.

- HT Wright: Trade and politics on the eastern littoral of Africa, AD 800-1300 . In: T. Shaw, P. Sinclair et al. (Eds.): The Archeology of Africa . London / New York 1993, ISBN 0-415-11585-X , pp. 658-672.

Remarks

- ↑ George, Abungo, Mutoro, in: The Archeology of Africa. 701

- ↑ Garlake: Africa and its Kingdoms. Pp. 81-83

- ↑ A summary of his journey

- ↑ Garlake: Africa and its Kingdoms. Pp. 88-89.

- ^ Wright: Trade and politics, pp. 659-665.

- ^ Wright: Trade and politics, pp. 665-670.

- ↑ Timeline of the arrival of the Portuguese

- ^ Steven Feierman, Economy, Society, and Language in Early East Africa, in: Philip Curtin, Steven Feierman, Leonhard Thompson, Jan Vansina, African History. From Earliest Time to Independence, London / New York 1995, pp. 101-129.

- ↑ Thomas Spear, The Shirazi in Swahili Traditions, Culture, and History, in: History in Africa 11 (1984), pp. 291-305.

- ↑ Kusimba: Swahili States. 141

- ^ John Iliffe , "Geschichte Afrikas", p. 76.

- ↑ Mark Horon, Nina Mudida: Exploitation of marine resources; evidence for the origin of the Swahili communities of east Africa: In The Archeology of Africa , edited by T. Shaw, P. Sinclair, B. Andah, A. Okpoko, London / New York 1993, ISBN 0-415-11585-X , Pp. 673-693.

- ↑ George HO Abunghu & Henry W. Mutoro: Coast-interior settlements and social relations in the Kenya coastal hinterland: In The Archeology of Africa , edited by T. Shaw, P. Sinclair, B. Andah, A. Okpoko, London / New York 1993, ISBN 0-415-11585-X , pp. 694-704.

- ↑ Kusimba: The Rise and Fall of Swahili States. Pp. 101-107.

- ^ John Iliffe, Geschichte Afrikas, Munich 1997, pp. 75f.

- ^ TH Wilson: Spatial Analysis and Settlement Patterns on the East African Coast. In: Paideuma 28 (1982), 201-219

- ^ Wright: Trade and politics, pp. 667-668.

- ↑ [1]

- ^ Wright: Trade and politics, p. 669.

- ^ Eyewitness report by Jaos de Barros and Hansd Mayr in GSP Freeman-Grenville: The East African Coast. Oxford 1962, pp. 86, 102, 108-10

- ↑ Garlake: Africa and its Kingdoms. Pp. 83-88

- ↑ Tomb in Gedi

- ↑ Garlake: Africa and its Kingdoms. P. 84