Nubian vault

Nubian vault is a vault construction method in earth building without formwork and often without gauges, which gets its name from traditional construction forms in Nubia . The ceiling geometry is the special case of a barrel vault or a dome , in which the cross-section takes the approximate geometric shape of a chain line .

history

With mud brick vaults executed were widespread in ancient times and since ancient Egyptian times on Nile between Cairo , and Upper nubia known. While larger temples were mostly flat-roofed, some chapels and tombs had barrel vaults made of mud bricks or house stones. Mud bricks were the main material for the walls and vaults of palaces. Ancient Egyptian vaulted structures are considered to be models for the stone barrel vaults in Roman architecture , whose vaulted structures reached a climax with the Maxentius basilica, which was built between 307 and 313 AD . In Nubia, which was influenced by Egypt, temples were made from carefully hewn stone blocks until Roman times . In the religious and civil structures built after the fall of the Meroitic Empire , house stones were almost only used for secondary purposes.

In the 6th century, at the same time as the Christianization of Nubia, there was brisk building activity. The newly founded and often fortified small towns were listed with rubble stones and adobe bricks. Together with the Egyptian tradition of specialized craftsmen, the ability to work house stone was largely lost at the end of the 7th / beginning of the 8th century. Most of the buildings were evidently built by the local population, as can be seen from the lack of care in the execution. Usually the adobe walls stood on a foundation and a base made of rubble stones. Some residential and church buildings had outer walls made of quarry stone up to the height of the supports for the barrel vault. Since adobe walls were more complex to manufacture, required more specialist knowledge and were therefore more expensive, quarry stones were used for the entire ground floor walls for reasons of cost, especially in simpler buildings. Different sizes and color variations in adobe bricks indicate that demolition material has been reused. There were no vaults made of stone, even stone arches were very rare.

The residential building architecture in Nubia was subject to changes in the social structure and different fashions, but remained relatively constant during the changing forms of rule until the 20th century. The economic focus of the predominantly small settlements has always been arable farming on the alluvial areas of the Nile floodplain, which until the 1970s were irrigated by sakiyas ( pumping stations ) driven by draft animals .

Vault construction in Nubia

The construction principle of traditional Nubian vaults followed the endeavor to avoid the need for formwork and falsework in order to save construction timber. Wood was and is in short supply in the region and was practically not used in house construction, not even for door posts or lintels. The vaults therefore have to support themselves during construction. Basically, all vaults consisted only of adobe bricks without tie rods made of wood or iron, as they sometimes occurred in ancient times. Vault shapes that require a certain strength of the material, such as cross vaults and generally three-dimensional intersections, are not possible with the soft material that cannot be subjected to tensile loads. Medieval bricks have the average dimensions of 34 × 18 × 9 centimeters with deviations of +/- one centimeter. They are made of Nile mud with the occasional additive like sand and finely chopped straw. Burned bricks were used very rarely, since the extremely rare rainfall is the only weather influence, erosion by the wind.

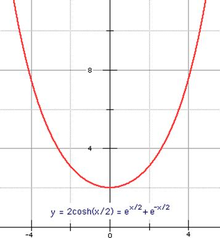

Due to the lack of wood, flat roofs in Nubia were limited to covering larger upper floor rooms and very simple, thin-walled houses; Palm wood trunks split lengthways were available as beams. Most of the houses have vaulted ceilings with the cross-section of approximate chain lines. This cross-sectional shape has proven to be the most favorable for loads that are carried vertically. The drawbacks are the ring tensile forces at the base of the dome, which limit the size of the nubic domes by a few meters without the need for tie rods. These ceilings are available as barrel vaults and hanging domes.

Both arches were used side by side in medieval Nubia. The rooms of the one or two-story residential buildings were covered by parallel barrel vaults. The Nubian churches built from the 6th to the 14th centuries usually had a slightly raised central dome or a somewhat wider barrel vault above the three- aisled prayer room and were surrounded on all sides by longitudinal barrel vaults. Most of the churches only survived until the beginning of the vault until the 20th century.

The two churches of Sabagura and the south church of Ikhmindi are dated to the 9th century , the central church of Ikhmindi is an early example from the 6th century. The river church of Kaw from the 13th century had a probably soaring central dome . In the Raphaelskirche in Tamit (from the 10th century) the construction of the Nubian hanging dome was particularly easy to recognize.

Barrel vault

Traditional barrel vaults consist of ring layers (bricks lined up lengthways) with constant wall thickness. In order to be able to work without auxiliary construction and only with a few horizontally stretched cords as alignment , the layers are inclined in the longitudinal direction of the vault. Special vaulted bricks are used that are slightly larger and narrower. With the Nile mud mortar used, the bricks adhere in place. The inclines are guided against the bulkhead of the barrel, with three to six layers being applied before the first layer runs continuously over the apex. Some old bricks were slightly wedge-shaped. In addition, small stones were placed in the butt joints that open outwards in order to counteract the mortar shrinkage during drying. For the same reason, it was customary to immediately cover each vault section with a layer of clay plaster, even if the surface was later invisible, because in the case of a ground floor ceiling the vault disappeared in the floor structure of the upper floor.

A special feature of Nubian rooms is a protrusion on the inside of the wall support of the barrel vault, which is relatively deep because of the towering dome. The wall thickness of the following storey was reduced by the width of the bearing, so that the ground floor wall had to be correspondingly thick in buildings with several storeys. In average residential buildings, the first floor had a wall thickness of 1.5 to 2 brick lengths, with another storey above it. The barrel vaults often began with a roll layer on the support to take advantage of the higher compressive strength of such a layer at the base of the vault.

In the case of longer barrel vaults, transverse arches were inserted in between so that the entire ceiling would not follow the collapse of the gable wall, which was laterally loaded by the vault. In the fortified city of Sabagura, the alleys between the closely spaced houses were also covered with a vault.

A special shape of the dome was a conical barrel vault over the semicircular apse in front of the east wall of the church . In the middle of the semicircular wall support, a small wall field was built up against which the standing ring layers leaned. The diameter of the curvature of the vault increased with the diverging apse semicircle in the direction of the church. The unsightly wall gusset at the beginning had to be filled with a spherical shape. Examples were found at the nave domed church of Tamit and the south church of Ikhmindi .

Hanging dome

Nubian domes were mostly designed as hanging domes, which are also known as outer circular domes . With these, the inner diameter at the base of the dome corresponds to the diagonals of the square below. Wall sections or arcade arches arranged in a square are usually used as supports , from the curvature of which the dome rises vertically. Four cylindrically curved vault sections, two of which are opposite each other, grow together above the diagonals of the base. In contrast to the cross vault, in which ridges form on the diagonal line of contact between the curved surfaces, the tiles in the hanging dome are on the same radius of curvature. The load of the hanging dome is evenly transferred to the entire bearing surface, while with the cross vault it is directed over the ridges to the four corner points.

The construction was carried out in a horizontal ring layer bond, in which each closed layer stiffened itself. The first layers were started with a slight inward slope of the bricks, but it was not so strong that the bricks would have pointed in their extended baseline towards the center of the geometric construction to prevent the bricks from slipping off before a layer was closed. Up to an inclination of around 30 degrees, the clay bricks held themselves in the mortar bed. Up to around two thirds of the vault height, the insufficient inclination was compensated for by moving the rows of bricks inwards in parallel. Above, there was an abrupt change to a steeper position, in which at least the last tile placed had to be held by a bar gauge.

In another, rarely performed method of laying, which was supposed to prevent slipping inwards, the bricks were slightly tilted radially (in plan view) in order to wedge each other. Compensating wedges, which were complex to produce at a distance of a few bricks, were required, which had to be inserted in order to compensate for the radial inclination.

Full circle dome

In the as inner circle dome designated shape, the inner diameter Kuppelfuß corresponds to the opposite Wandauflagern. There must be a circular horizontal support on the same level. The base ring of the dome, which lies within the corners of the square room to be covered, requires an additional support structure. There are two classic options for creating corners , both of which were also used in Nubia in Christian times: the gradual approach to the round shape by laying horizontal brick layers ( trompe ) and the pendentives protruding from the corners parallel to the diagonals , which form a spherical outer surface .

The mud bricks were mainly laid in horizontal ring layers with inwardly sloping storage areas. For the geometrically correct shape of the dome a lyre was used , as it was also known in European dome construction. This is a rotating rod or rope at the level of the support, with which the constant distance to the center point and the bearing inclination can be determined. If the lower point of the lyre is in the center of the base circle, the result is a semicircular dome. A rotation around a center circle of the base results in a dome with an elliptical cross section.

The Nubian medieval domed buildings generally did not strictly follow a geometric model and were rather negligent in their construction. A lyre often seems to have not been used. Judging by the ruins that have been preserved, there were no hemispherical domes in the Middle Ages, the cross-sections were raised in the shape of a chain or beehive. The span of Nubian domes was very small. The largest dome diameter was measured at the nave dome church of Tamit at 3.3 meters, followed by the monastery church in ar-Ramal at 3.1 meters. The only exception to a larger dome, which was the only one to cover the entire nave, was the dome church of Kulb with a diameter of 7.5 meters (on the bank of the Nile near the island of Kulubnarti , 12th century at the earliest).

Today's village houses in Upper Egypt and Northern Sudan are rarely built from adobe bricks and no longer have vaulted ceilings. In their place, walls made of fired bricks and flat ceilings plastered with cement have been replaced. Traditional vaults with imprecise geometry, negligent construction and with horizontal ring layers, the storage areas of which hardly incline inward, can still be seen on the numerous Islamic graves of saints in the region and occasionally in dovecotes .

Modern variants of the Nubian vault

In contemporary architecture, the Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy emerged from the 1940s with the planning of Nubian vaulted buildings made of adobe bricks. In the succession of Fathy, numerous residential projects in wood-poor and arid countries fall back on the traditional roof forms of the Nubian mud brick vaults. Nubian vaults (and other vault construction methods) combine inexpensive and ecological building with an easy-to-learn working technique.

West Africa

Since 2000, the Association La Voute Nubienne has had more than 200 Nubian vaults built in Burkina Faso using simplified and modified techniques. More than forty bricklayers from Burkina Faso , Mali and Togo were trained to build the vaults together with as many apprentices in the building trade without wooden support structures. This program is known as La voute nubienne (VN). It has grown steadily since then, especially due to the increasing demand for the construction of houses, churches, mosques and hotels in Burkina Faso and in the neighboring countries of the Sahel zone . In contrast to the traditional Nubian construction, the flat vaults can be an alternative for flat roofs even with the wood shortage in the arid regions of West Africa.

The Association pour le Développement d'une Architecture et d'un Urbanisme Africains (ADAUA) built several dome housing estates and public buildings from fired bricks in West Africa in the 1980s. One example is the regional hospital in Kaédi , Mauritania.

literature

- Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann , Peter Grossmann : Nubian research (= archaeological research. Vol. 17). Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1988.

- Gernot Minke : Earth building manual. The building material clay and its application. Ökobuch, Staufen near Freiburg 1997, ISBN 3-922964-56-7 , pp. 238-257.

Web links

- T. Granier, A. Kaye, J. Ravier, and D. Sillou: The Nubian Vault. Earth Roofs in the Sahel. Association La Voute Nubienne, Ganges (France) 2006

- Nubian vault construction in Mexico using straw / clay blocks. caneloproject.com (model house for ecological construction in Mexico)

- John Norton: Woodless Construction. Unstabilized Earth Brick Vault and Dome Roofing without Formwork. (PDF; 1.0 MB) Building Issues, Vol. 9, No. 2, 1997, pp. 3–26

Individual evidence

- ^ FW Deichmann, P. Grossmann: Nubische Forschungen. Berlin 1988, pp. 119-121.

- ^ FW Deichmann, P. Grossmann: Nubische Forschungen. Berlin 1988, p. 154.

- ^ FW Deichmann, P. Grossmann: Nubische Forschungen. Berlin 1988, pp. 128, 149-153.

- ↑ a b F. W. Deichmann, P. Grossmann: Nubische Forschungen. Berlin 1988, p. 157 f.

- ^ FW Deichmann, P. Grossmann: Nubische Forschungen. Berlin 1988, p. 156 f.

- ↑ G. Minke: Lehmbau Handbuch. The building material clay and its application. Staufen near Freiburg 1997, pp. 242–244.

- ^ Franz Stade: stone constructions. 1907, new edition: Reprint-Verlag, Leipzig 2003, p. 254, ( online at google books ); Gernot Minke: Earth building manual. Fig. P. 243; John Norton: Woodless Construction. Using unstabilsed earth bricks and vault and dome roofing in West Africa. In: Building Issues, Vol. 9, No. 2, 1997, p. 10: Sketch of a lyre

- ↑ The Nubian Vault Association (AVN) ( Memento of the original from January 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Campaign to build clay roofs in the Sahel