Amadu Bamba

Amadu Bamba , also Ahmadou Bamba Mbacké ( Wolof ) or Sheikh Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Habīb Allāh ( Arabic ); (* 1853 in Mbacké-Baol, Senegal ; † July 19, 1927 in Diourbel ) was a marabout and the founder of the Murīdīya , one of the most important Islamic brotherhoods in Senegal. To this day, the Murīdīya consists of a number of clans and families that the brothers, sons and disciples of Amadu Bamba founded.

Life

Ascent to the marabout

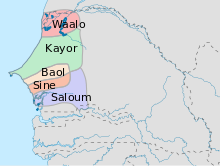

Bamba came from a long-established Marabout family in the eastern part of the Kingdom of Baol . His grandfather Maharram founded the village of Mbacké-Baol here, where Bamba was born in 1853. His father Momar Antasali was a scholar and marabout of the Qadiriyya , the oldest brotherhood in Senegal. Bamba learned the Koran by heart at an early age and studied Islamic sciences under the guidance of his father and other Senegambian scholars of his time. At the age of 15 he wrote a 1,600-verse poem on Sufism with the title Masālik al-ǧannān fī ǧamʿi mā farraqahu ad-Daimān .

When the French allowed Lat Dior , the lady of Cayor , to re-establish his kingdom in 1871 , Bamba moved to the village of Mbacké-Kayor, which his father founded there. Through his religious knowledge and piety he earned himself the reputation of a marabout, so that Lat Dior also consulted him on political decisions. When Momar was dying in 1883, he entrusted Bamba with the care of his younger sons. He returned a year later to his home village of Mbacké-Baol and brought some followers with him who fled from the turbulence in Cayor that was connected with the dissolution of the kingdom.

Conflicts between the original residents of the village and the numerous devotees that Amadu Bamba attracted forced him to leave the village around 1888 and start a new village nearby. This village, called Darou Salam, grew very quickly due to the increasing number of followers. In 1889 Amadou Bamba was introduced to the Qādirīya order by a student of the Mauritanian sheikh Sidiyya Baba. Bamba wrote numerous poems in praise of the Prophet in the late 1880s and early 1890s , poems that are still recited by his followers today. Around 1891 he had a religious experience that is referred to in the sources as a "prophetic revelation".

Confrontation with the colonial power, exile and house arrest

The French colonial government was concerned about Bamba's growing following and his ability to wage war against the colonial power . As early as 1889, shortly before the conquest of Jolof , the colonial administration began to collect information about him. In 1891 the Saint Louis Political Affairs Bureau appointed Amadu Bamba. On this occasion he declared his loyalty to the French and announced the names of his most loyal followers. However, due to his rapidly growing following, the French remained suspicious of him. After the French had brought Baol under their control, Bamba evaded in the spring of 1895 with his closest followers to Jolof, which still had a certain autonomy. There he gained influence over Samba Laobe Penda, which the French administration had set up as head after the exile of Alburi Ndiaye. In August of the same year, however, he was captured by a French unit and then exiled to Gabon for an indefinite period .

The exile in Gabon raised Bamba's reputation even further. A number of legends spread among his followers about his miraculous survival from torture, privation and attempted executions, which further expanded his movement. On the ship to Gabon, Bamba, who was forbidden to pray, is said to have freed himself from his iron chains. He is said to have jumped overboard into the ocean and started praying on a prayer rug that emerged from the water. When the French threw him in an oven, he sat down and had tea with Mohammed . In a cage with wild lions, the wild animals lay down by his side and slept.

During Bamba's absence, Bamba's half-brother Sheikh Anta Mbacké and Ibra Fall, one of Bamba's closest followers, developed good relations with the French colonial administration. Your submissions meant that Amadu Bamba was allowed to return to Senegal in 1902. There he was received like a hero in the docks of Dakar . During his subsequent stay in Cayor and Baol, Bamba was almost always in the company of Shaykuna, the follower of and son-in-law of Sidiyya Baba. However, a tumultuous reception for him in Dakar in November 1902 worried the colonial authorities.

On the basis of rumors that Bamba was preparing a holy war, Ernest Roume, the governor-general of French West Africa , had him arrested and exiled again in June 1903, this time to Trarza , Mauritania , where he was placed under the care of Sidiyya Baba . Amadu Bamba kept in close contact with his followers through letters. In one of these letters from 1903, he divided his followers into four categories, assigning each group specific tasks. Relatives like his brother Sheikh Anta took advantage of Amadu Bamba's absence during this time to enrich themselves with the gifts of his followers.

In 1907 Bamba applied to Jean-Baptiste Théveniaut, the civil administrator of Trarza, to be allowed to return to Senegal. The French realized that by isolating Amadou Bamba they could not stop the expansion of his movement and let him return to Senegal, this time to the village of Chéyen in Jolof. There they held him in a kind of house arrest, although Amadou Bamba was regularly visited by his followers, who brought him numerous gifts. Among those who joined him were now many members of the old ruling families who had lost their political power to the French.

Cooperation with the French

At the end of 1910, Amadu Bamba wrote a circular to his followers, in which he urged them to obey the colonial power, which had brought peace and was too powerful to wage jihad against them . The French, realizing that Bamba had no warlike intentions, then allowed him to return to Diourbel in Baol in 1912 , an event that marked the transition to good relations with the colonial government and a new phase of expansion of his brotherhood, known as Murīdīya since 1909 , marked. The governor of Senegal announced in an official letter in 1913 that relations with Amadu Bamba were now normal and that the Murīden were behaving very correctly.

Bamba's lesson of hard work served French interests. Amadou Bamba was made a Knight of the Legion of Honor in 1918 for his assistance in the recruitment of soldiers for the First World War . Only occasionally did the movement show hostility to the French. In August 1912, for example, a confession from Amadou Bamba was found on a supporter, which read: "O you Jews and Europeans, die and do not hope for help tomorrow!"

His following continued to grow. On the Prophet's birthday in 1914, he received 4,000 pilgrims from all over Senegal, four years later that number had already quintupled. The admiration of his followers for him partly exceeded that of a normal marabout. A French official reported in 1912 that when Bamba was passing through Mbacké-Baol, he was greeted with shouts of "Our God is returning".

During these years, however, Amadu Bamba increasingly lost control of his movement to those around him. A French official wrote as early as 1911 that Amadu Bambu was to a certain extent only the honorary chairman, while other sheikhs, his relatives and students, had actually taken control.

From 1924 until his death, Bamba dedicated the construction of a large mosque in the village of Touba , where he had received his early revelation. He also set it up as a burial place. The French administration did not allow the building until 1925 after Amadu had paid it an amount of 500,000 francs.

Bamba died on July 19, 1927 in his home in Djourbel. Since the French administration feared uncontrollable demonstrations, they secretly removed his body at night and brought him to Touba for burial.

Amadu Bamba was an extremely prolific writer. His field of activity covered various areas of Islamic literature such as theology, Islamic law and Sufism. Much of his work is kept in the city of Touba, which he founded.

Today's admiration

Bamba is still considered to be the innovator of Islam among his followers . Traditionally, they justify this reputation with a Hadith from Abū Dāwūd , according to which Allah should send the Muslims a renewer of the faith at the beginning of every century. In deviation from traditional Islamic teaching, Bamba proclaimed that submission to the marabout and hard work were necessary for salvation. Bamba's followers touch murals with his portraits with their foreheads or kiss them because, in their view, the images emanate from the Baraka (power of blessing).

The memory of Ahmadu Bamba's exile by the French in 1895 is cherished among the intellectual elite of the Murids. It is said to have taken place because Ahmadu Bamba refused to renounce Islam. To commemorate this event, the Murids introduced a new pilgrimage in 1980, the Magal of the Two Rakʿas on September 5th. This commemorates that when Ahmadu Bamba was summoned by the French governor, he insisted on performing his prayer with two rakʿas .

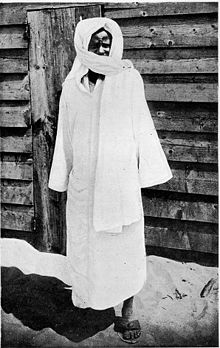

Only one authentic photograph of Bamba has come down to us. It shows him in the classic headgear and clothing of a marabout, with a scarf hiding most of the face. Different versions of this image are shown throughout Senegal and in the Murid communities in Paris and New York .

Honorary nicknames of Amadu Bamba are Sériñ Touba ("Holy Man of Touba "; Wolof) and Chādimu r-Rasūl (Arabic, "Servant of the Prophet").

literature

- Cheikh Anta Mbacké Babou: Fighting the Greater Jihad: Amadu Bamba and the Founding of the Muridiyya of Senegal, 1853-1913 . Ohio 2007.

- Donal B. Cruise O'Brien: The Mourides of Senegal. The political and economic organization of an Islamic brotherhood. Oxford: Clarendon Press 1971. pp. 37-57.

- Allen F. Roberts, Mary Nooter Roberts: "L'aura d'Amadou Bamba. Photography et fabulation dans le Sénégal urbain" in Anthropologie et Sociétés 22 (1998) 15-40. PDF

- David Robinson: Paths of accommodation: Muslim societies and French colonial authorities in Senegal and Mauritania, 1880–1920 . Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 2000. pp. 208-225.

- Rüdiger Sesemann: Aḥmadu Bamba and the emergence of the Murīdīya: Analysis of religious and historical backgrounds. Investigation of his life and teaching based on the biographical work of Muḥammad al-Muṣṭafā Ān. Berlin 1993. Islamic Studies 166 Digitized by Menadoc

Web links

- Literature by and about Amadu Bamba in the catalog of the German National Library

supporting documents

- ↑ See Christian Coulon: Women, Islam and baraka. In: Donal B. Cruise O'Brien, Chritian Coulon: Charisma and Brotherhood . Oxford 1988, pp. 113-135, here p. 125.

- ↑ See Robinson: Paths of accommodation . 2000, p. 210.

- ↑ See Robinson: Paths of accommodation . 2000, p. 212.

- ↑ See O'Brien: The Mourides of Senegal. 1971, p. 40.

- ↑ See Robinson: Paths of accommodation . 2000, p. 212.

- ↑ See Robinson: Paths of accommodation . 2000, p. 213.

- ↑ Cf. O'Brien 1971, 41.

- ↑ See Robinson: Paths of accommodation . 2000, p. 214.

- ↑ See Robinson: Paths of accommodation . 2000, pp. 214-216.

- ↑ See O'Brien: The Mourides of Senegal. 1971, p. 43.

- ↑ See Robinson: Paths of accommodation . 2000, pp. 216-218.

- ↑ See Robinson: Paths of accommodation . 2000, p. 218.

- ↑ Cf. O'Brien 1971, 52.

- ↑ See O'Brien 1971, 54.

- ↑ See Robinson: Paths of accommodation . 2000, p. 221.

- ↑ Cf. O'Brien 1971, 52

- ↑ Cf. O'Brien 1917, 45.

- ↑ See O'Brien 1971, 57.

- ↑ See Robinson: Paths of accommodation . 2000, p. 223.

- ↑ See O'Brien 1971, 46.

- ^ Cit. O'Brien 1971, 50.

- ↑ Cf. O'Brien 1971, 47.

- ↑ See O'Brien 1971, 54.

- ↑ See O'Brien 1971, 55.

- ↑ See Robinson: Paths of accommodation . 2000, p. 224.

- ↑ See O'Brien 1971, 48.

- ^ Allen F. Roberts, Mary Nooter Roberts: A Saint in the City. Sufi Arts of Urban Senegal. In: African Arts, Vol. 35, No. 4, Winter 2002, pp. 52–73 + 93–96, here p. 55

- ↑ See Donal B. Cruise O'Brien: Charisma Comes to Town: Mouride Urbanization 1945-1986. In: Donal B. Cruise O'Brien, Chritian Coulon (Ed.): Charisma and Brotherhood . Oxford 1988, pp. 135-157, here p. 150f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bamba, Amadu |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Chādim ar-Rasūl |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Founder of the Sufi - Brotherhood |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1853 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mbacké-Baol , Senegal |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 19, 1927 |

| Place of death | Diourbel |