Timbuktu

| Tombouctou Timbuktu |

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Coordinates | 16 ° 46 ′ N , 3 ° 0 ′ W | |

| Basic data | ||

| Country | Mali | |

| Timbuktu | ||

| circle | Timbuktu | |

| ISO 3166-2 | ML-6 | |

| height | 263 m | |

| surface | 147.9 km² | |

| Residents | 54,453 (2009 census) | |

| density | 368.2 Ew. / km² | |

| politics | ||

| Maire | M. Ousmane Hall | |

Timbuktu ( German [ tɪmˈbʊktu ], French Tombouctou [ tõbukˈtu ]) is a Malian oasis town with 54,453 inhabitants (2009 census).

etymology

The name supposedly means "fountain of the Buktu". According to legend, Buktu (French spelling Bouctou ) was a slave who was left here with a herd of goats by the Tuareg to guard a well. The name is supposed to mean "woman with a big belly button," but it may be a folk etymology . Some historians see in this tradition the justification of the former upper class of Timbuktu for the social stratification, i.e. the division into light-skinned gentlemen, the Tuareg, and dark-skinned vassals, the Bella (see below "Population").

The French linguist René Basset derives the name from an old Berber word root that means "far away" or "hidden". Thus the name would have to be translated as "the distant well", that is, on the southern edge of the desert. In recent studies it has been asserted on various occasions that the place was not originally founded by the Tuareg at all, but by the Songhai of the surrounding area and that the derivation of the name from their language, presented in the middle of the 19th century by the Africa researcher and historian Heinrich Barth, is also in Must be considered. According to Barth, the name would be correctly Tombutu and would mean “place in the dunes”, which would also make sense.

geography

Timbuktu is located on the southern edge of the Sahara , the desertification of which is causing the city most of the problems. The sand spreads all over the streets. In the past 20 years, the desert is said to have advanced about 100 kilometers further south.

The city is located about 12 kilometers north of the Niger River, which flows past the Massina region in a large arc from the south-west, turns here at the northernmost point of its course in a south-easterly direction and later flows into the Gulf of Guinea on the coast more than 2000 kilometers away . Only when there is a strong flood do long-dried tributaries of the Niger, nicknamed the “canals of the hippopotamuses”, fill up and cause severe flooding in some parts of the city; This last happened in 2003. In the early modern era, a 13-kilometer canal connected the town of Kabara, the actual port of the city, with Timbuktu. This artificial tributary of the Niger gave the residents direct access to the river during the flood and thus the sailing ships and pirogues to bring goods into the city. The canal is silted up and only visible as a ditch.

Timbuktu has been a center of Trans-Saharan trade for centuries , and at the end of the 19th century around 400 caravans with 140,000 camels and around 22,400 tons of loads passed through here every year. However, it is still difficult to reach the place. Navigation is only possible when the water level allows it. The roads through the savannah from the south silt up quickly and are temporarily impassable. From the north, through the desert, the route is reserved for two groups of travelers: the now rare salt caravans of the Tuareg (especially from Taoudenni ) and the modern adventurers who are on the trail of desert romance. The most modern way of arrival is via Timbuktu Airport ( IATA airport code : TOM), which is regularly served by the capital Bamako .

climate

The climate is desert-like, there is always a dry, hot wind (" Harmattan ") from the Sahara. Thorn bushes, tamarisks , acacias and gorse can be found here in sparse vegetation . The African baobab tree and palm trees as well as a number of useful trees grow here.

The average annual temperature is 28 ° C, with May and June being the hottest at around 34 ° C. The average annual rainfall was measured as 170 mm. July and August are the wettest months at around 56–66 mm. The downpours can be torrential and cause great damage to houses and mosques made of clay. In 1771 the al-Hana mosque collapsed during such a storm and buried 40 people under it.

| Timbuktu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall for Timbuktu

Source: wetterkontor.de

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

population

Due to the eventful history and the location at the intersection of major trade routes, the population of Timbuktu is made up of members of various ethnic groups. These include Berbers , Moors , Songhai , Mandinka and the Bambara . Some of them live in their own quarters; In the city and its surroundings, representatives of the Tuareg with their camels and the Fulbe with their herds of cattle are more likely to be found. The Bozo live as fishermen on the Niger.

The Bella , dark-skinned fishermen and small farmers live on the banks of the Niger, possibly descendants of the original population of the area and who were forced into a relationship of dependency by the Tuareg in the early Middle Ages. The tradition about the founding of Timbuktu and the slave girl Buktu could be understood as an echo of this development (see "Etymology" above). Until about 50 years ago they were exploited by the Tuareg as a kind of slaves, whereby the individual Bella families were not subject to any individual "owners", but had to work and pay tribute collectively as unfree for the Tuareg, primarily the confederation of the Kel Antessar. Since Mali's independence, they have been officially free, traditionally feel they belong to the Tuareg society and mostly speak the language of their former masters, the Tamascheq .

The lingua franca is French. The Songhai language , with the Koyra Chiini dialect , is predominantly spoken among the population of the Timbuktu area . In addition, a tenth speak Tamascheq or the Moorish dialect of Arabic.

Traditional architecture

The original construction in Timbuktu was due to the lack of stones. Therefore, it was mainly built with clay. The older reports speak of beehive-like circular buildings, in which mostly the poorer population lived. The view of Timbuktu made by René Caillié in 1828 still shows numerous houses of this type.

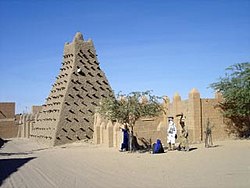

In the 15th century at the latest, a more elaborate architectural style prevailed, which mainly shaped the houses of the upper class (administrative officials, merchants and scholars). This form of clay architecture, which has become known as the “Sudanese style”, is particularly evident in the mosques with their towers tapering towards the top. Constructions made of wood, which were clad with clay, formed the basic structure. In this way, two-story buildings could be erected, in which the lower floor was used as a Koran school , storage and sales room or workshop, while the upper, mostly airy floor served as a living area. The private libraries were also located here in the houses of the scholars. However, building with only partially solid material led to massive structural damage or collapses during heavy rains. After each rainy season, the walls had to be refinished and houses that were no longer worth repairing were often simply given up. (See, for example, the illustration "Street in Timbuktu" below.)

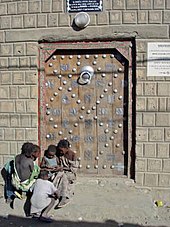

In addition to the traditional clay architecture, there are multi-storey houses made of neogene limestone in Timbuktu , which are modeled on Morocco and Mauritania . The style was probably brought to the Niger by Djuder Pasha's mercenaries at the end of the 16th century. The facades are structured vertically with pilasters and adorned with "Andalusian" windows and solid wooden doors following the Moroccan model. The windows were not originally glazed, but rather covered with filigree wooden grilles. The doors are characterized by ornate sheet iron fittings and geometric patterns made from large iron nails, which are modeled on what was once al-Andalus , the part of Spain that was ruled by Muslims between 711 and 1492.

history

Foundation and early days

According to information from the Chronicles of Timbuktu ( Tarikh as-Sudan and Tarikh al-Fettach ), which was written much later in the 17th century, Timbuktu was founded before 1100 AD by nomadic Massufa Tuareg at a watering place near the Niger Arc . Probably the origins go back to the 9th or 10th century and it is probable that black African Songhai must be regarded as the founder of the place. However, according to new archaeological research by Douglas Park, Yale University, there were those as early as 500 BC. The forerunner town of Tombouze , founded in the 3rd century BC , the ruins of which are just under 10 km south of today's town. After the first millennium of our era, the place quickly developed into a flourishing trading post on the important caravan route from Egypt via Gao to Koumbi Saleh in the West African empire of Ghana . Islam was probably spread on Niger through traders from southern Algeria. In the beginning, Timbuktu was by no means as important as a junction of trade routes and as a place of Muslim education, as is asserted today in various books and Internet articles. The economic boom and the associated cultural prosperity of the city did not occur until the 14th and 15th centuries. It seems that the early Timbuktu was in competition with another trading post about 25 km to the east called etwairraqqā, which, according to Arab geographers, was the westernmost outpost of the Ghana Empire. With the decline of Ghana, the traders apparently turned to Timbuktu, which offered better opportunities for handling goods due to its close proximity to Niger.

The time of the great West African empires

Incorporation into the Mali Empire

The city belonged to the Mali Empire from the 13th century or early 14th century . It is not clear whether the integration took place through open conquest or whether the city - also to protect against the Tuareg in the north and the Mossi in the south - became dependent on Mali. But even the suzerainty of Mali could not prevent a devastating attack by the Mossi in 1328. The attack suggests that Timbuktu had already established itself as the center of the salt and gold trade by this point . The city had about 10,000 to 15,000 inhabitants at that time.

Already at this time the city was known in southern Europe, because it appeared in the middle of the 14th century on the portolans , the Catalan or Mallorcan world maps, as the residence city "Ciutat de Melli" of "Rex Melli", King of Melli. On the famous map by Abraham Cresques from 1375, the legendary king is depicted with a nugget of gold. This meant Mansa Musa , the black sultan of Mali, who made his legendary pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 . From this pilgrimage, on which he was allegedly accompanied by 60,000 servants, it is reported that he carried two tons of gold with him and distributed it generously in Egypt. These accounts contributed to the formation of legends about an allegedly immensely wealthy city. After his return from Mecca, Mansa Musa commissioned a Muslim architect from Andalusia, who accompanied him on his return, to build the clay mosques of Djinger-ber Mosque and a residence.

The Europeans had received numerous reports from North African traders and caravan drivers. In addition, there were written records of travelers who stimulated the fantasies in Europe. The Moroccan Ibn Battūta (1304–1368), who was born in Tangier , made an extensive journey through numerous Islamic countries in the 14th century. The journey that took him across East Africa to India also took him to Timbuktu in 1352. He confirms that Islam had completely replaced the old African beliefs there, but could not muster up any understanding that the women there went "naked", i.e. unveiled, on the streets. Overall, however, the visitor from Morocco does not know much about the city of significance. Apparently, Walata and Gao were far more important at the time, both economically and in terms of educational development.

Belonging to the Songhai Empire

Timbuktu experienced its heyday in the 15th and 16th centuries after the decline of the Moorish trading metropolis Walata . The caravan metropolis on the Niger was then the largest city in the region and had an estimated 15,000 to 25,000 inhabitants. At certain times of the year, when the salt caravans came from the north and the buyers from the south and west, the number of people could briefly double. The numbers of up to 100,000 or even 200,000 inhabitants sometimes cited in popular scientific literature are pure speculation, because even at a time when desertification was not as advanced as it is today, the area around Timbuktu could by no means have fed such a large number of people.

The city belonged to the Songhai Empire during this period and was considered a rich city. The Songhai ruler Sonni Ali had conquered Timbuktu in 1468 and had some of the Muslim intellectuals executed because they were loyal to the Mali empire and to the Massufa Tuareg, with whom they were related. The city was administered by a governor ( tinbuktu-koi ), whereby this governor was repeatedly considered by foreign travelers to be the ruler of the entire empire.

The main source of wealth was the trade in salt and slaves . Timbuktu was the main hub for slaves and eunuchs (from the Mossi country) destined for Morocco and Egypt. There was also the gold trade, although the supply declined in the 16th century after the European sea powers had set up their trading bases on the West African coast (catchphrase: "The caravel is the death of the caravan .") In return, metals and finished metal products arrived from the north , Horses , weapons , silk , jewelry , literature and dates to Timbuktu. In addition to the coveted gold, ivory , musk , cola nuts , pepper , rubber , leather goods and millet from southern West Africa were exchanged. In addition, Timbuktu developed as the center of Islamic intellectual life in West Africa. At the Sankoré Mosque there was a madrasa , comparable to a medieval university, where the Arabic language , rhetoric , astrology , jurisprudence and the scriptures of the Koran were taught. There were also 150 to 180 Koran schools at which religious and legal subjects were often taught by a single teacher. Most of the mosques in Timbuktu date from the Songhai era, which ended with the Moroccan conquest in 1591. The last to be restored was the 14th century Sankoré Mosque in 1581 (989 A.H.) and completed in its current size.

One of the most important sources is the travelogue of Leo Africanus (1485–1556?), Who was born in Granada and expelled from there to North Africa . He traveled through North Africa on behalf of the Moroccan sultan and, according to his own account, came to the city on the Niger between 1510 and 1512. Whether he was actually in Timbuktu is controversial, as, for example, his statements about the direction in which the Niger flows are completely wrong. When he later came to Italy through captivity, he described Sudan and especially Timbuktu for European readers. His manuscript, which was not originally intended for printing, was published in Venice in 1550, but the editor Ramusio had supplemented the data with imaginative exaggerations and thus cemented the myth of the immeasurably rich city in Africa. In particular, the figures relating to the gold trade had apparently been deliberately falsified in order to increase sales of the book.

Timbuktu in the early modern period

The motives for the conquest of Timbuktu by the troops of the Moroccan sultan Mulai Ahmad al-Mansur (1578–1603) are varied. On the one hand, the Sultan was interested in redirecting the gold trade, which was increasingly oriented towards the European-controlled trading centers on the West African coast ( Senegal and the Gold Coast ), back to North Africa. Secondly, the Sultan saw from the dynasty of Saadian , which in itself the status of Sharif , ie descendants of the Prophet Mohammed took to complete, in the Ottoman Empire , which up after Algeria had extended a dangerous rival, because the Ottoman Sultan considered himself the ruler of all devout Muslims. But it also seems that al-Mansur saw in his elite troops, consisting of Spanish renegades , a danger to his own position. Therefore he sent a force of about 4,000 men, which was called "Arma" (Spanish: "weapon") and had modern firearms. The army was under the command of Majorca- born Djuder Pasha, who had come to Morocco as a slave and had quickly made a career as a eunuch at the court of al-Mansur. The three-month march through Western Sahara was costly, although the army had the best guidance at the time, e. B. compass and sextant.

According to tradition, the Songhai Empire was defeated on the last day of the year 999 or, according to the Muslim calendar, on the first day of the year 1000 (mid-October 1591 AD). The Moroccans set up garrisons first in Gao and then in Timbuktu, could not hold out against attacks by the Tuareg and the peoples south of the Niger knee, including the Bambara , and concentrated their activities in the immediate vicinity of the cities. The British explorer Alexander Gordon Laing got to know the last Moroccan Pasha Uthman Ibn Abi Bakr, who had to give up Timbuktu in 1828 . The city, which itself was never the capital of one of the West African empires, could never develop its old heyday and lost its importance. In addition, the Atlantic trade had become significantly more important than the Trans-Saharan trade . The West African gold was no longer transported through the Sahara, but reached the Atlantic coast, which is why the current state of Ghana was called the " gold coast " until it gained independence from Great Britain in 1957 .

In the 17th and 18th centuries the Arma gained an almost autonomous position in Timbuktu, which was far too far from Morocco for the Sultan to have effective rule there. The pashas, who came from the ranks of the mercenaries and their descendants, were merely confirmed in their office and paid a tribute - often only symbolic - to the Moroccan ruler. Timbuktu had no noteworthy protective structures such as wall ring or fortified gates, and so the outskirts of the city, in which the less well-off residents lived, often only in tents or huts made of straw mats, were the target of attacks by the Tuareg from the hinterland. The domination of the Arma in the area around Timbuktu ended in 1737 with the defeat against the Tuareg in the battle of Toya (20 km away from Timbuktu). In 1771 the nomads invaded the Sankoré district, forcing the residents to seek refuge in the mosque. The power of the Arma was limited to the urban area. The Bambara, who had established an empire further west on the central reaches of the Niger, tried to bring Timbuktu under their control, although the city had long since lost its economic importance.

Between 1823 and 1862, the city was under the suzerainty of the Fulani - Caliphate of Massina , but the real authority was in the hands of the Kunta -Clans of al-Baqqai that were in the 19th century as the most important Koranic scholars in western Sudan. The Sheikh Sidi Ahmad al-Baqqai negotiated a contract with the Fulbe in 1844 after they had interrupted the essential food supplies from the Niger Inland Delta to Timbuktu. The treaty stipulated that Timbuktu would not be militarily occupied by the Fulbe. The internal affairs of the city were to be regulated by the Songhai elite under the direction of the Qadi , the chief judge, while the Caliph of Massina was represented only by a tax collector. In fact, in view of his reputation and his spiritual authority, the Sheikh was actually the strong man in Timbuktu who could afford to refuse to extradite the Christian Heinrich Barth to the overlord in Massina and to violate the laws of Islam to the caliph in a fatwa accuse.

In view of the threat posed by the jihad of the Fulani preacher Hajj Umar , al-Baqqai was forced to find allies from 1860 onwards. First he made contact with the French in Senegal, but realized that he could not expect any military help from there. So he tried to get closer to the Caliphate of Massina, but could not prevent it from being conquered by Umar's troops in 1862. Timbuktu came under the control of religious fundamentalists. Two years later, al-Baqqai gathered an army consisting of the Fulbe, Kunta Moors and Tuaregs, liberated Timbuktu and drove the followers of Umar from Massina. After the death of al-Baqqai in 1865, the Tuareg regained power over the trading city, which resulted in the city's final economic decline. Only the conquest by the French in the years 1893-1894 ended the rule of the desert nomads.

The race to Timbuktu

To what extent Europeans came to Timbuktu before 1800 is still a matter of speculation. Certain evidence from the Middle Ages suggests that the Italian Benedetto Dei came to Niger in the 15th century, but there is no real evidence. The journey of the French Anselm d'Ysalguier , who is said to have lived in Gao and possibly also in Timbuktu between 1402 and 1410, could be a fantasy product from later times. It can also be assumed that the American seaman Robert Adams, who wrote a book about his experiences in 1816, was not in Timbuktu during his time as a prisoner of the Moors , but merely evaluated descriptions by Moorish merchants and issued them as eyewitness accounts.

The Scot and British officer Alexander Gordon Laing was the first European to reach Timbuktu in 1826. Since he was slain by Moors on the way back and his notes disappeared without a trace, it was only René Caillié , who traveled to Timbuktu in 1828 disguised as an Arab, who was able to report on this city in Europe. His report corresponded so little to the ancient myths and the long-cherished hopes and expectations of Europeans that to this day there are stubborn doubters, especially in Great Britain, who deny that he was ever in Timbuktu.

However, Caillié's reports were confirmed twenty-five years later by the German Africa explorer Heinrich Barth . Barth stayed in Timbuktu from September 1853 to April 1854 on behalf of the British. He was under the protection of the city's chief Koran scholar, Sidi Ahmad al-Baqqai, and negotiated a treaty with the Sheikh and the Tuareg leaders. In this, Great Britain undertook to protect the city and the surrounding area from further access by the French. The support from Great Britain would have meant for the political leadership in Timbuktu that they could have freed themselves from the suzerainty of the Fulbe. In view of the rapprochement between the French and the British taking place at the same time, however, this treaty was not ratified in London, to the disappointment of al-Baqqai .

A significant success for science, however, was the fact that Barth was able to evaluate numerous historical writings and thus prove the historicity of the African continent. His travelogue became the basis for all later research on the history of the country on the Niger and especially of Timbuktu. Today a house still reminds of Barth's presence, although it is not the building in which the traveler lived, because, as the African explorer Leo Frobenius writes, it collapsed in August 1908 during a storm.

Timbuktu in the colonial age

At the beginning of 1894, despite the bitter resistance of the Tuareg and against the will of the government in Paris, Timbuktu was finally occupied by French colonial troops under the command of the later Marshal Joseph Joffre and the colony "Afrique Occidentale Française", or "AOF" ( French West Africa ), incorporated. A first military column under the command of Colonel Bonnier, which had marched to Timbuktu despite the prohibition of the new civil governor from French West Africa, was ambushed by the Tuareg and was completely destroyed. The leader of the attack was the son of a tribal chief who had signed the contract with Heinrich Barth in 1854, and he himself had welcomed the Austrian Oskar Lenz as the supposed son of Barth when he visited the city in 1880 .

In order to justify the militarily and politically nonsensical conquest in public, the colonial- friendly press sent the well-known journalist Félix Dubois, who wrote a travelogue with the tricky title Tombouctou la Mystérieuse ( Mysterious Timbuktu ). In the bestseller, the conditions in Sudan were glossed over and France was certified that with the occupation of the old trading cities of Djenné , Mopti and Timbuktu - despite the current economic situation on Niger - a great future awaits that will bring the colonial power here a second India . Dubois had bought old manuscripts in Djenné and Timbuktu, which he gave to the National Library in Paris. The most important works of the early 17th century, the Tarikh al-Fettakh (Book of the Seeker) and the Tarikh as-Sudan (Book of Sudan) , were edited and translated by the famous orientalist Maurice Delafosse . This made it possible for the first time since the days of Heinrich Barth to thoroughly and scientifically research the history of the country on the Nigerknie and to make the European public aware of it.

In order to keep the number of French troops and local auxiliary troops as low as possible and thus save costs, the French colonial administration pursued a conciliatory course with the Tuareg and pronounced an amnesty for all leaders who had resisted the occupation in 1893 and 1894. The leader of the local resistance, the nephew of Sheikh Ahmad al-Baqqai, Za'in al-Abidin Ould Sidi Muhamad al-Kunti, had to withdraw to the north with his family and his library, first to Adrar des Ifoghas and then to Tassili n ' Ahaggar , where he was also driven out by French troops in 1902. A large part of the family library is said to have been lost during the escape, i.e. either hidden or deliberately destroyed. Until the 1920s, Abidin Ould Sidi Muhamad organized attacks on French positions in the Sahara and Niger from what is now Mauritania in order to hit the colonial rulers. But since these increasingly had superior military power, the rebels attacked the supply caravans. In 1910, for example, the caravan that was traveling to Taoudeni with groceries was plundered, which resulted in the workers in the salt pans starving to death without exception.

In 1916, the Ullemmeden- Tuareg uprising broke out along the Niger River in the wake of one of the worst drought disasters the Sahel has ever known. A number of the Tuareg groups in the surrounding areas of Timbuktu and Gao joined the survey. After the uprising was put down, the leaders who had taken part in the fight against France were removed and replaced by loyal people. Overall, this measure systematically and deliberately undermined the traditional authority of the tribal leaders. The economic basis was affected, for example by the liberation of the slaves, which of course was never carried out consistently during the French colonial period.

The arbitrary demarcation between the AOF and Algeria across the Tuareg region broke off trade relations to the north, so that Timbuktu lost even more economic importance, while the trading cities in the Niger Inland Delta (Djenné, Mopti) flourished again. The last big old-style caravan with several thousand camels came from the Tafilalet oases to Timbuktu in 1937 . However, the salt trade with Taoudenni in the north of today's Mali remained important .

Administratively, Timbuktu became a sub-command, subordinate to a colonial officer with the rank of major. The chief commander resided in Gao. The troops stationed in Timbuktu consisted mainly of local camel riders ("méharistes") and were stationed in "Fort Bonnier", which was named after the commander whose column had occupied Timbuktu in 1893 as the first. The garrison was ineffective, however, and so in 1923 Moorish warrior nomads from the north of the country were not only able to make the area around the city unsafe, but also attack Timbuktu themselves and put down a detachment of camel riders before reinforcements arrived for the Mopti garrison. According to unconfirmed reports, the warriors were acting on behalf of the displaced Sheikh of Timbuktu, Za'in al-Abidin ibn al-Baqqai.

After the final subjugation of the nomads, Timbuktu sank into insignificance. One of the most important events was the arrival of the “Raid Dubreuil - Haardt ”, the “Mission Transsaharienne” initiated by the car brand Citroën , which arrived in Timbuktu on January 7, 1923 with eight half-track vehicles specially equipped for desert trips from the Algerian town of Touggourt . During the " Croisière Noire ", which ran from Touggourt to Antananarivo in Madagascar , which was accompanied by a great deal of press , Timbuktu was bypassed. Another visit there was not considered spectacular enough. The expansion of the trans-Saharan route opened up in this way to a main road suitable for automobiles and a connection between the colonies of Algeria and AOF was never realized during the colonial period. This applies to the plans for the Trans-Saharan Railway ( Tunis - Lake Chad - Timbuktu - Dakar ), which was designed around 1880 . The resumption of the project was discussed again and again between the world wars, but the plans never came close to a concrete implementation because the responsible commissions recognized that the costs for construction and maintenance were in no reasonable relation to the expected trade volume would have.

Except for officers and representatives of trading houses, Europeans and Americans rarely came to Timbuktu. Mostly they were ethnologists and writers. In 1927 the American Leland Hall visited the city. Ten years later, the Paris correspondent for the Frankfurter Zeitung , Friedrich Sieburg , crossed the Sahara on a bus and wrote a travel report in which he described Timbuktu as a desolate place at the end of the world.

For a French officer, being posted to Timbuktu was equivalent to a punitive transfer. As the German travel writer and ethnologist Herbert Kaufmann found out in the 1950s, only Kidal in the north of the country ( Adrar des Ifoghas ) was considered even more bleak. There were hardly any tourists in the true sense of the word among the Europeans and Americans who visited Timbuktu during the colonial period, as the city did not have any appropriate infrastructure. The journey from Djenné was still quite difficult. Hence, writers such as Kaufmann or ethnologists such as Horace Miner (see bibliography) came primarily . In the years after 1960 the hinterland up to the Algerian border in the Adrar des Ifoghas was unsafe, as there were repeated armed clashes between the Kunta and the Tuareg due to the impending shortage of pastureland and water supplies.

Contemporary developments

After September 22, 1960, Timbuktu was part of the Republic of Mali, which was granted independence by France. As early as the 1950s, there had been clashes between the Tuareg and black administrative officials who were still in French service at the time. After independence, the conflict between the desert nomads and the representatives of the state power, which was trying to make the uncontrollable Tuareg settled, escalated. In the 1990s there was an uprising among the Tuareg with the aim of declaring a state of their own. The rebellion ended in 1996 with a symbolic weapon burning. The "Peace Flame" in Timbuktu commemorates the historic peace agreement.

On April 1, 2012, Timbuktu was captured by Tuaregs who, reinforced by mercenaries returning from the civil war in Libya , are fighting for a state of their own . In the days before, the Tuareg had also occupied the important cities of Kidal and Gao . The Tuareg announced that they wanted to consolidate their profits and not march on Mali's capital Bamako and offered negotiations on a ceasefire. The putschist government of Mali also announced negotiations for a ceasefire, despite having justified the March 21 coup with poor counterinsurgency conduct.

On April 5, the Tuareg were expelled by the Islamist West African group Ansar Dine . For the next nine months she controlled the city together with Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQMI). The Islamists tried to enforce a strict form of Sharia law and destroyed several world-famous mausoleums (see Destruction by Islamists 2012 ). At the end of January 2013, Timbuktu was retaken by French and Malian troops as part of the Opération Serval . It became known that shortly before taking the city, the Islamists had set fire to an important library with many manuscripts. (See the Ahmed Baba Research Center section of this article.) In March 2013, Islamists tried again to gain a foothold in the city.

History of Timbuktu in dates

| date | event |

|---|---|

| around 900–1100 | first settlement by Songhai (farmers and fishermen) |

| around 1100 | Establishment of the Timbuktu trading post by the Tuareg (according to chronicles) |

| around 1320 | (presumably peaceful) incorporation of Timbuktu into the Mali Empire |

| 1324 | Pilgrimage of the Malian ruler Mansa Musa to Cairo and Mecca, return via Timbuktu |

| after 1327 | Foundation of the Sankoré Mosque with a loose association of Koran schools (so-called "University of Sankoré") |

| 1328 | short-term conquest and partial destruction of the city by the Mossi of Yatenga |

| 1352 | Ibn Battuta visits Timbuktu and the Mali Empire |

| around 1440 | Mali loses power, the Tuareg rise to become overlords of Timbuktu |

| around 1468 | Sonni Ali conquered Timbuktu and incorporated the city into the Songhai Empire |

| around 1500 | Kadi Mahmud Aqit does not implement Askia Muhamad's anti-Jewish instructions |

| 1512 | Leo Africanus on a diplomatic mission in Timbuktu |

| 1556 | Ahmad Baba is born as Abu al-'Abbas Ahmad Ibn Ahmad al-Takruri al-Massufi in Arawan |

| 1581 | Extension of the Sankoré Mosque |

| 1591 | Conquest of the city by Moroccan mercenaries and deportation of scholars to Marrakech |

| 1627 | Death of the scholar Ahmad Baba |

| 1640 | Drafting of Tarikh as-Sudan by Mahmud Kati; Parts of the city are being destroyed by floods |

| 1737 | Defeat of the Arma against the Tuareg in the Battle of Toya |

| 1752 u. 1754 | severe earthquakes destroy part of the city |

| 1770 | Victory of the Aulliminidan Tuareg over the Arma of Timbuktu |

| 1771 | Collapse of the al-Hana mosque with many deaths |

| 1806 | Mungo Park drives past Kabara down the Niger River |

| around 1820 | the Kunta clan of al-Baqqai settled in the north of Timbuktu and became the leading spiritual and political power |

| 1826 | the Fulbe of Massina gain suzerainty over Timbuktu |

| 1826 | the Briton Alexander Gordon Laing is proven to be the first European to reach Timbuktu and is murdered on the way back |

| 1828 | René Caillié is disguised as a Muslim in Timbuktu |

| 1831 | the Fulbe of Massina occupy Timbuktu with their army |

| 1844-1848 | Conflict between the Fulani rulers of Massina and the Kunta al-Baqqai for supremacy in Timbuktu |

| 1853-1854 | Heinrich Barth spends half a year in Timbuktu and the surrounding area as a guardian of the Sheikh al-Baqqai |

| 1859-1864 | Presence of Jewish merchants from southern Morocco and brief establishment of a Jewish cult community that is tolerated by the “dhimmi” status |

| 1862/63 | End of the Empire of Massina, Timbuktu comes under the control of the Tukulor Empire of Haj Umar |

| 1864 | The Tukulor are expelled from Timbuktu and Massina by an army from Fulbe, Kunta and Tuareg led by Ahmad al-Baqqai |

| 1865 | Death of Sidi Ahmad al-Baqqai; Timbuktu comes under the influence of the Tuareg again |

| 1880 | Oskar Lenz visits Timbuktu |

| 1893 | Short-term occupation by Colonel Bonnier and massacre of the occupiers by the Tuareg |

| 1894 | final occupation by Colonel Joffre and start of the resistance under Za'in al-Abidin al-Baqqai (until about 1923) |

| 1910 | Destruction of the supply caravan for Taoudeni by Moorish insurgents |

| 1913-1915 | Drought disaster in Azawad north of Timbuktu and uprising of the Aulliminidan Tuareg against the French |

| 1915-1918 | Revolt of the Aulliminidan-Tuareg against the French (so-called "Revolt of the Kaossen") |

| 1923 | Arrival of the Trans-Saharan expedition from Citroën ("Croisière Noire") |

| 1960 | Mali is given independence |

| 1963 | Armed conflict with the Tuareg in the area north of Timbuktu |

| 1967 | UNESCO Conference in Timbuktu, start of safeguarding the Timbuktu manuscripts and books |

| 1973 | Foundation of the CEDRAB (Center de Documentation et de Recherches Ahmad Baba) |

| 1988 | Timbuktu is placed on the World Heritage List |

| 1990 | The conflict between Mali and the Tuareg escalates |

| 1996 | Peace agreement between the state of Mali and the Tuareg |

| 2003 | severe damage to the historic cityscape after flooding |

| 2006 | Timbuktu is the world capital of Islamic culture |

| 2012 | Timbuktu is first occupied by Tuareg rebels and later by Islamists |

| 2013 | Recapture by Malian and French armed forces as part of the Opération Serval |

religion

Position of Islam

Timbuktu must have been an Islamic city from the beginning. A distinction must be made between the elite and the people. While the Berber upper class adhered to the new faith, the lower classes admitted to Islam, but continued to follow animistic beliefs and rites, some of which mixed with the new religion to form a specific variety of Islam. It was not until the early 19th century that a stricter and purer version of the religion was enforced in the wake of the Fulani jihad and under the influence of the Kunta marabutin.

The population of Timbuktu and the surrounding area are exclusively Muslim. However, pre-Islamic beliefs and practices were demonstrably common among the Songhai until the middle of the 20th century (H. Miner). Even among the Tuareg there are magical ideas that cannot be reconciled with Islam and that have been heavily criticized by Koran scholars to this day.

Islamic scholarship

In the late Middle Ages, and especially in the 16th century, Timbuktu was a center of Islamic learning, but contrary to what is often erroneously claimed, it was not a holy city like Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem. Islamic scholars believe that the conquest of the city by the Moroccans in 1591 had an impact on the piety of the residents of Timbuktu, as educational centers suffered as the city gradually became impoverished, which led to a dilution of Islam and the rise of old, pre-Islamic beliefs . According to orientalists, the conquest of the Niger Arch by Moroccan troops led to an increased immigration of North African clergy who, in contrast to the intellectual Koran scholars of Timbuktu, preached a popular form of Islam (including cult of saints, use of amulets, exorcism). At the beginning of the 19th century, Timbuktu got caught up in the maelstrom of Islamic renewal - also known as Fulani jihad - and experienced an upswing in religious education, which resulted in stricter observance of religious regulations. Since the early 19th century, the Moorish Kunta - between 1830 and 1895 under the al-Baqqai clan - dominated the city's religious life. Their sheikhs, especially Sidi Ahmad al-Baqqai, were regarded as great scholars who pursued the peaceful implementation of the strict doctrine, but at the same time strictly rejected the armed dissemination of the faith - in contrast to the Fulbe of Massina, who established themselves as overlords of Timbuktu .

Open-mindedness and xenophobia

Timbuktu was often referred to in literature as the “forbidden city” and was considered a refuge for fanatical Muslims. This view can no longer be held. As a trading city, Timbuktu was rather open, and Islam practiced in West Africa was very tolerant until the Fulani jihad (early 19th century). The Murabatin from the al-Baqqai clan, who are decisive in Timbuktu, are unanimously described as cosmopolitan and by no means xenophobic. What European travelers perceived as Islamic fanaticism turns out, on closer reading, to be an expression of an unreflected fear of foreigners, which can be found in all cultures. The aversion to potential competitors in the tough and hardship of the Trans-Saharan trade must be taken into account when interpreting this phenomenon. This non-religiously motivated xenophobia was easily mixed with religious prejudice, since the "stranger" was not a Muslim. Heinrich Barth described this phenomenon comprehensibly at various points in his travel book. On the other hand, individual travelers came to Timbuktu at a time of political upheaval, such as Alexander Gordon Laing in 1826 or Heinrich Barth in 1853. The Kunta ruling in Timbuktu were in open conflict with the Tukulor (Fulbe) of Massina, the nominal overlords of the city, which represented a more radical and thus more xenophobic position within Islamic theology. The rival political groups saw strangers as puppets to use in the struggle for supremacy. It should not be forgotten that the era of the great Sahara expeditions coincided with the colonial expansion of France in north-west Africa and that the Christians could be seen as spies and agents of a potential European occupying power. In the age of colonialism, the supposedly religiously motivated hatred of Christians turned out to be a perfect argument for the European side to justify occupying a “stronghold of fanaticism”, as Timbuktu was described by Saharan researchers such as Gerhard Rohlfs , Henri Duveyrier and Oskar Lenz .

The question of the Jewish minority

To what extent there has been a Jewish minority for a long time and whether or when it converted to Islam or was forced to convert is currently still controversial. It is conceivable that the representatives of Jewish trading houses from Andalusia or Mallorca resided in Timbuktu and participated in the gold and slave trade, although it should be noted that the majority of merchants resided in Sidschilmasa in southern Morocco and Tamentit in southern Algeria . The role of the Jews in Timbuktu is likely to have been similar to that of the Jews in medieval Europe, that is, they were tolerated and presumably had the status of dhimmi , i.e. taxable wards of the rulers of Mali or Songhai. They hardly played a political role, and they also hardly had any influence on the cultural development of the strictly Islamic city. Reports of large Jewish settlements in the Timbuktu area, such as Tindirma, or nomadic tribes of Jewish faith in the central or southern Sahara also do not correspond to reality.

Anti-Semitic tendencies

The Songhai ruler Askia Muhamad passed anti-Jewish laws under the influence of the Algerian preacher al-Maghīlī . The preacher had already taken care of the extinction of the Jewish community in the Tuat oases, namely in Tamentit. These regulations provided for the expulsion or forced conversion of the Jews in his empire on the one hand, and the death penalty or at least the expropriation of all Muslims who continued to trade with Jews on the other. There is no unanimous opinion among Africa historians about the concrete effects of these laws. It seems certain that the Kadi of Timbuktu, Mahmud Aqit, refused to enforce the anti-Jewish regulations in Timbuktu with all severity and moved the ruler to return to a tolerant interpretation of the Koran. Recent research seems to show that there are still families in Timbuktu whose ancestors were forced to convert to Islam by the Songhai rulers around 1500, but who have secretly preserved the memory of their Jewish heritage. The realm of the imagination, however, includes newer theories that claim that large masses of Jewish settlers left the Sahel region, especially the area around Timbuktu, to the south and settled in Ghana and Nigeria , where their descendants allegedly profess Judaism again today.

Jewish merchants from Morocco were not officially admitted again until after 1860, and at times there were more than ten adult Jewish men in Timbuktu, so that they formed a cult community according to religious law and were subject to the status of dhimmi . However, they were not allowed to set up a synagogue that was recognizable as a house of prayer, for example, and they were not allowed to talk to Muslims about religion, as this could have been interpreted as proselytizing. They also had to be buried in a separate cemetery.

Christians as visitors

Christians only stayed in Timbuktu as visitors before the end of the 19th century. They have no influence whatsoever on internal development, for example on politics or education. The attempt of the Catholic missionary order “ White Fathers ” to proselytize among the slaves and the Bozo in the years immediately after the conquest of the city between 1895 and 1900 failed, but the fathers were not attacked. The fact that they accepted the missionaries as interlocutors on questions of theology speaks for the tolerance of the Muslim notables - a reminiscence of the peaceful discussions that Ahmad al-Baqqai and Heinrich Barth had had almost half a century earlier. In view of their unsuccessful missionary work, Father Augustin Hacquard left the city and only wrote an ethnological text about it, which is still of considerable value as a historical document (see bibliography). Hacquard's brother Auguste Dupuis stayed in Timbuktu, resigned from the order, married a local woman and converted to Islam. In the 1920s and 1930s he lived in the city and did ethnographic studies. Under his Muslim name Yacouba (Jacob) or the nickname “le moine blanc de Tombouctou (the white monk of Timbuktu)”, he was the first “dropout” in Sudan to be a well-known personality and was greeted by numerous visitors - including ethnologists - for advice and Mediation tackled.

Culture and sights

World heritage

| Timbuktu | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| The Sankore Mosque |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | ii, iv, v |

| Reference No .: | 119 |

| UNESCO region : | Africa |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1988 (session 12) |

| Red list : | 1990–2005, since 2012 |

The three big mosques

The three mosques that dominate the skyline, the Djinger-ber Mosque , the Sankore Mosque and the Sidi-Yahia Mosque and 16 cemeteries and mausoleums count since 1988 to the world heritage of UNESCO . However , contrary to the wishes of the Mali government, the historic townscape with its characteristic clay construction and numerous mosques from the 13th to 15th centuries was not included; In the opinion of the World Heritage Committee, the interventions by modern buildings were already too far advanced. In 1990 the sites were added to the Red List of World Heritage in Danger. They date from the 14th century and have been renovated several times over the years. With the help of UNESCO, a conservation program was set up so that the sites could be removed from the red list again in 2005 after the worst damage caused by a flood in 2003 had been repaired. Three other mosques from this period, the El Hena Mosque , the Kalidi Mosque and the Algourdour Djingareye Mosque , have been destroyed.

Mausoleums and tombs

The most famous of the mausoleums is that of Sheikh Abul Kassim Attouaty, who died in 1529. In addition, the graves of the scholar Sidi Mahmoudou and the restorer of the mosques, the Qādī Al Aqib, who died in 1548 and 1583, respectively, should be mentioned. In 2001 the Islamic Organization for Education, Science and Culture (ISESCO) named Timbuktu the “Islamic Capital of World Culture” for Africa for 2006.

Destruction by Islamists in 2012

After the military coup of March 21, 2012 and Azawad's declaration of independence on April 6, 2012 by the Tuareg rebels of the MNLA , the Islamist groups Ansar Dine , AQMI and MUJAO gained control in northern Mali. In early May 2012, members of Ansar Dine and AQMI destroyed the Sidi Mahmud Ben Amar mausoleum in Timbuktu, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and threatened attacks on other mausoleums. At the end of June 2012, Timbuktu was placed on the Red List of World Heritage in Danger due to the armed conflict in Mali . Shortly thereafter, the destruction of the UNESCO- listed tombs of Sidi Mahmud, Sidi Moctar and Alpha Moya continued under mockery of UNESCO.

In 2014 there was a mission of the International Committee of the Blue Shield (Association of the National Committees of the Blue Shield, ANCBS) in Timbuktu for the protection of cultural property.

The occupation of Timbuktu by Ansar Dine and AQMI was narrated and cinematically processed in 2014 in the film “ Timbuktu ” by Abderrahmane Sissako .

education

Before the pilgrimage of Mansa Musa (1324–1325), Islamic education did not play a prominent role in Timbuktu. Walata was far more important in this regard, as Ibn Battuta attests. The ruler of Mali apparently brought back a large number of books from Mecca and Egypt from his pilgrimage, which perhaps laid the foundation for a future educational system. Mansa Musa sent a future imam from the Sankóre Mosque to Fez for training , which leads to the conclusion that the level of Islamic education in Niger was still very rudimentary. Only in the 15th and 16th centuries was the city with the so-called Sankoré University a center of education in the Islamic world. However, this educational institution is not a university with a centralized administration and central facilities. It was a loose association of Koran schools, some of which - as elsewhere in the Islamic world - taught the reading and understanding of the holy scriptures of Islam. In some cases, however, lessons were also given by highly qualified lawyers and theologians. In this respect the organization is quite comparable to that of the medieval colleges of Oxford and Cambridge. According to a single source from the 17th century, there should have been between 150 and 180 such Koran schools in Timbuktu before the Moroccan conquest. It is reported that the reputation of the scholars who taught at the leading Koran schools reached as far as the Andalusian city of Granada. The number of 25,000 students who are said to have studied there at the same time is unrealistic. None of the authors who come up with this number can name a source nor determine at what time between 1100 and 1600 so many students are said to have lived in Timbuktu. The city could neither feed nor house them. Realistically, the number should have been less than 2000.

Research in the modern sense was not carried out in Timbuktu. Rather, the “lectures” were about imparting knowledge in the sense of a scholastic interpretation of recognized legal and theological texts, which were then discussed. Islamic teaching provided the framework in any case. In this respect, too, teaching in Timbuktu did not differ fundamentally from that at other Islamic universities (Fez, Cairo, Damascus) or from Christian-European universities such as Bologna, Oxford or Paris. Apparently medical knowledge and skills, as they were typical of the Islamic world in the Middle Ages, were to be found in Timbuktu. It is reported that the eye was operated on as early as the 14th century. However, it is only likely to be the treatment of cataracts known at the time for almost 2000 years, the so-called star stitch . Nothing is known of more advanced surgical methods. Recently made claims that scholars in Timbuktu developed the number zero and discovered the modern solar system 200 years before Copernicus have no historical basis.

The Timbuktu Books

Books or manuscripts in Arabic script were imported from Morocco and especially from Egypt , but old works were copied in Timbuktu by professional scribes. Until the French conquest of the city in 1894, there was no book press in Timbuktu. Mansa Musa, King of Mali from 1312 to 1337, is said to have brought a whole load of camels from Cairo from his pilgrimage. It is not known whether these books were made available to the mosques that were subsequently built in Timbuktu. The number of writings that were kept in Timbuktu in the Middle Ages can no longer be determined.

Most of the books were privately owned by the families that produced leading theologians and lawyers for generations. The libraries were probably very extensive. Ahmad Baba (1560–1627) complained that he had the smallest collection in his family with just 1,600 volumes. Whether there were public libraries in the 16th century, i. H. in the premises of the large mosques, is controversial. The Songhai ruler Askia al-Hajj Muhammad b. Abi Bark (1493–1528) is said to have given the Djinger-Ber Mosque valuable editions of the Koran that should be accessible to all believers. A later ruler, Askia Dawud (1549–1583) is said to have set up public libraries in the large cities of his empire, of which, however, there is currently no archaeologically unambiguous trace. There never was a kind of university library in the modern sense.

The claim, which is often brought into play in this context, that 400,000 to 700,000 books were stored in Timbuktu, including writings that were more than 1000 years old, must be taken with extreme caution, as the city is responsible for such gigantic number of folios would not have offered any storage capacity. Experts estimate the number of books at the moment to be less than 100,000 and the total number of manuscripts still in existence in northern Mali to a total of 300,000. Among these writings, however, there are very many documents that consist of only one or two sheets, mostly copies of theological or legal reports that had been prepared by the city's scholars at the request of state and religious authorities throughout North and West Africa.

Numerous documents from the library of Sankóre have survived, some of which were microfilmed during a retrieval by the United States Library of Congress. Larger holdings were lost around 1900 when Muslim scholars left the city in the face of the French occupation and took their libraries with them, such as Sidi al-Baqqai's nephew Abidin. They evidently feared that the French might threaten them with the same fate as the notables in earlier times after a conquest (execution by Sonni Ali or deportation by Djuder Pascha). For fear of confiscation, numerous books are said to have been buried in the vicinity of the city, causing them to be irrevocably destroyed. In the period that followed, larger holdings were sold to European collectors and libraries. There can be no question of a large-scale robbery of African cultural treasures by the colonial rulers. The existence of large private libraries was known in specialist circles, but it was not until 1965 that the holdings were sifted through and gradually conserved on the initiative of the British orientalist John O. Hunwick, primarily with financial support from UNESCO and several Western European countries (especially Norway and, more recently, Luxembourg ) as well as the USA. The first and so far most important center for the preservation and evaluation of the manuscripts in Timbuktu, IHERI-AB is named after the important Koran scholar and lawyer Ahmad Baba and is mainly financed by grants from non-Islamic and non-African countries. In 2001 the South African government launched the first African initiative to save the Timbuktu books. The construction of a library in the square opposite the Sankóre Mosque is currently being prepared.

During the conflict in northern Mali since 2012 there was a risk of destruction by Islamists. In fact, some manuscripts were lost when the bandits left in a library fire in January 2013. The fact that manuscripts from the library of the Ahmed Baba Institute were hidden in private houses meant that most of them could be preserved.

Ahmed Baba Research Center

The Ahmed Baba research center , French original name Institut des hautes études et de recherches islamiques Ahmed Baba , Timbuktu (IHERI-AB, formerly CEDRAB for “Center de documentation et de recherche Ahmed Baba”, English The National Ahmed Baba Center for Documentation and Research in Timbuktu) serves primarily to preserve and research these manuscripts. Most of the texts are still in the possession of local families. There are two types of documents: those that originated in the region and those that came here with extensive trade from other parts of the Arab world. The research center was founded at the beginning of the 1970s (1973 or before) and has been operating since 1977. Mali collaborates internationally with institutes in Luxembourg, Norway, England, Kuwait and the USA. The directors are Mohamed Gallah Dicko (Directeur) and Sidi Mohamed Ould Youbba. The oldest dated document is from 1204.

While fleeing from the French and Malian troops advancing into Timbuktu, Islamists set fire to the Ahmed Baba library building in January 2013. The full extent of the destruction cannot yet be foreseen, it said. Among other things, not because there are reports that documents have been secretly outsourced in good time. According to the Malian government, up to 100,000 manuscripts were stored in the library, which was founded in 1973.

music

The Festival au Désert has been held in Timbuktu since 2003, every January . Originally, members of the Tuareg from the region met for this event to dance, sing and make music together or, for example, to maintain the cultural heritage of their people with camel races and games. The festival originally took place in Essakane , 70 km east of Timbuktu , which has become a meeting place for the Tuareg and numerous artists from Africa and all over the world. For security reasons, the Festival au Désert was moved to the outskirts of Timbuktu in 2010. In 2012 the festival took place under military guard due to terrorist actions in the previous year. Due to the critical situation in northern Mali, the Festival au Desert 2013 will be relocated to the oasis city of Oursi in Burkina Faso . Participants have so far included Ali Farka Touré (CD Talking Timbuktu 1994 with Ry Cooder ), Amadou & Mariam , Damon Albarn (lead singer of the British band Blur ), Robert Plant (former singer of Led Zeppelin ) and Bono (singer of the rock band U2 ) ( 2012).

Sports

The city's football club is AS Commune Timbuktu (Association sportive de la commune de Tombouctou) . On June 29, 2007, the team lost 2-0 in the national cup competition of Mali when they participated in the capital city club Djoliba AC Bamako in their own stadium. The Timbuktu Regional League received a donation for equipment and material in May 2007. CM Timbuktu, the Club militaire de Tombouctou , also took part in the Malian cup competition in the past. The city has a stadium, the Stade omnisport , which was completed in 2003 and has space for 1,200 spectators. The construction costs were around 185 million CFA francs (around 280,000 euros). There is a basketball and handball court on the site. Timbuktu was also a frequent stage of the Dakar Rally .

economy

Pre-colonial period

Timbuktu has been exclusively a trading center since its inception. The sterile surrounding area did not allow large-scale food production, so that most of the food had to be brought from the Djenné-Mopti region on the Niger to Kabara. The cost of living was correspondingly high. Only meat was supplied by the Tuareg from the surrounding area, but given the fact that the nomads only slaughtered animals in emergencies, meat was a scarce commodity that only the wealthy merchant class and the representatives of the royal administration could afford. Timbuktu played a particularly important role as a stopover for the salt trade. In Kabara the large salt plates were cut up and prepared for transport on the river. The arrival of the Azelai , the great salt caravan from Taoudeni in the north of today's Mali, was also an important high point in the annual cycle of social events in the city.

The canal, which has connected Kabara with Timbuktu since the 17th century, has dried up again and again in modern times, so that the goods had to be transported by land. This allowed the Tuareg time and again to paralyze trade with the city they claimed for themselves. The caravans often had to travel the relatively short stretch with armed force to protect themselves against attacks. Halfway between the two places was a valley basin that was often used for such attacks. With the Tuareg it was called "ugh - umaira (you don't hear anything)". Anyone who fell into the hands of robbers there could no longer hope for any help (according to Heinrich Barth).

present

Today Timbuktu is a poor city. With a few exceptions, the historic city center is in poor condition. The Yobouber store was expanded in 2003 for around 900 million CFA francs (1.37 million euros) and has 25 shops, a butcher's shop, sanitary facilities and offices. With Canadian help, the sewage disposal of the market has been improved.

Today there is nothing left of the glory of the old days, the population is poor and for the most part unemployed. Timbuktu looks even more barren than other cities in the Sahel region . All that remains of the classic trade goods of the past is the salt, which is still delivered from the north, from Taoudenni , and portioned in Timbuktu or Kabara and sold to traders who transport it upriver on pirogues .

Twin cities

-

Chemnitz , Saxony, Germany (since 1968)

Chemnitz , Saxony, Germany (since 1968) -

Saintes , France (since 1978)

Saintes , France (since 1978) -

Hay-on-Wye , County Powys, Wales , United Kingdom (since 2006) (The small town, world-famous for its antiquarian booksellers, outpaced competitors such as Glastonbury and York as judges believed Timbuktu and Hay-on-Wye were in their Very similar in character, especially in relation to large amounts of old books.)

Hay-on-Wye , County Powys, Wales , United Kingdom (since 2006) (The small town, world-famous for its antiquarian booksellers, outpaced competitors such as Glastonbury and York as judges believed Timbuktu and Hay-on-Wye were in their Very similar in character, especially in relation to large amounts of old books.) -

Kairouan , Tunisia

Kairouan , Tunisia -

Tempe , Arizona, United States (since 1991)

Tempe , Arizona, United States (since 1991)

Sons of the city

- Sidi Ahmad al-Baqqai (1803–1865), important Islamic scholar and politician

- Henri Dupuis-Yacouba (1924–2008), general and politician in Niger

- Seidnaly Sidhamed (* 1957), fashion designer, known under the name Alphadi

- Ali Farka Touré (1939–2006), musician

Synonymous with remote place

Since the city had for centuries the legendary reputation of a place that is far away and almost inaccessible, it has become a synonym in Europe for a remote place whose real existence is not even proven. In this function, the name appears in various languages, including German, Dutch and English. Therefore, the joke was always immediately clear to Anglo-Saxon readers or moviegoers when Donald Duck in the comics by Carl Barks at the end of a story either voluntarily, for fear of punishment, or forcibly emigrated to this mystical city. In the last picture of such comics you can usually see him breaking into the distance, following a sign that says “Timbuktu”. In Disney's Aristocats , the evil butler Edgar is finally locked in a suitcase with a sign with the destination Timbuktu emblazoned on it. The name is often used in the Garfield comic series , either as an address on a package (in which Garfield stuffed young chick Nermal) or, as with Donald Duck, as a place of escape.

The signposts in the Donald Duck stories may be inspired by an actually existing sign in Zagora in the south of Morocco , which is a popular tourist attraction there. The city of Zagora is home to the last caravanserai north of the Sahara on this route , and a sign has been on the outskirts for many decades, which shows the only few caravans left today, the way to Timbuktu south of the Sahara. It bears the inscription "Timbuktu 52 days" , which illustrates the proverbial remoteness of Timbuktu for tourists in an amusing way. The old signpost has now been replaced by a new one with an identical label.

See also

- History of Mali

- List of cities in Mali

- Timbuktu - a feature film on the city's latest history

literature

- Michel Abitbol: Tombouctou et les Arma: de la conquête marocaine du Soudan nigérien en 1591 à l'hégémonie de l'Empire Peulh du Macina en 1833. Paris 1979, ISBN 2-7068-0770-9 .

- Heinrich Barth: Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa in the years 1849 to 1855. Gotha 1857–1858, esp. Vol. 4 u. 5.

- Tor A. Benjaminsen, Gunnvor Berge: Une histoire de Tombouctou . Arles 2004, ISBN 2-7427-4908-X .

- Sékéné Mody Cissoko: Tombouctou et l'empire Songhay: Épanouissement du Soudan nigérien aux XVe - XVIe siècles. Paris 1996, ISBN 2-7384-4384-2 .

- Robert Davoine: Tombouctou: fascination et malédiction d'une ville mythique. Paris 2003, ISBN 2-7475-3939-3 .

- Marq De Villiers, Sheila Hirtle: Timbuktu: Sahara's Fabled City of Gold . New York 2007.

- John Hunwick: Timbuktu . In: Encyclopaedia of Islam. New edition. Vol. 10, Leiden 2000, pp. 508-510 (article by a leading expert on Timbuktu's history).

- John Hunwick (Ed.): Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sa'di's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other Contemporary Documents. 2nd Edition. Leiden 2002 (English translation of one of the most important source works, with numerous annotations).

- Shamil Jeppie, Souleymane Bachir Diagne (eds.): The Meanings of Timbuktu. Paul & Co Pub Consortium, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7969-2204-5 ( Download in 26 PDFs from the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa ).

- Horace Miner: The Primitive City of Timbuctu. Princeton 1953 (verb. New York 1965).

- Regula Renschler: At the intersection of major trade routes. Life in the desert - using the example of Timbuktu. In: Katja Böhler, Jürgen Hoeren (Ed.): Africa. Freiburg im Breisgau / Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-89331-502-0 , pp. 96-103 (more journalistic, originally from a publication by the Federal Agency for Civic Education ).

- Elias N. Saad: Social History of Timbuctu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables, 1400-1900. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-13630-3 .

- Anthony Sattin: The Gates of Africa: Death, Discovery, and the Search for Timbuktu. New York 2003, ISBN 0-312-33643-8 (about the first research trips to Timbuktu, especially Mungo Park , Alexander Gordon Laing and René Caillié ).

- John Spencer Trimingham: A History of Islam in Western Africa. London / Oxford / New York 1962.

Web links

- Bibliography on the history of Timbuktu by Prof. John O. Hunwick; Literature up to 2000 (PDF; 135 kB)

- Bibliography on the history of Timbuktu and the Tuareg on the Niger Arch until approx. 2006 ( Memento from February 12, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Text excerpt from Barths Reisewerk u. Figure ( Memento from October 1, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Status report 2005 of the World Heritage Committee on the removal of Timbuktu from the Red List , p. 23 f. (English; PDF; 394 kB)

- Article about the Islamic manuscripts in Timbuktu (PDF; 193 kB)

- Article about the exhibition of Timbuktu manuscripts in the American Library of Congress (with numerous illustrations)

- Dreams look different. diepresse.com, January 16, 2009 (article about the Timbuktu myth)

- The Genesis of the City of Timbuktu. Sankore. Institute of Islamic-African Studies International (PDF; 1.1 MB)

- Photos from 1906

- House where Barth lived in Timbuktu

- Heinrich Barth and Timbuktu (PDF; 283 kB)

- Timbuktu website of the University of Oslo with valuable links

- Charlotte Wiedemann: Portrait Abdelkader Haidara: From the sand holes into the digital library. qantara.de

Remarks

- ↑ Association des maires francophones ( Memento of the original from May 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ INSTAT: Results of the 2009 census (PDF; 835 kB)

- ^ René Basset: Mission au Sénégal. Paris 1909, p. 198.

- ↑ arte-TV (May 3, 2012 8:55 am to 9:40 am): Timbuktu's lost legacy . “It is a race against time, because Timbuktu is in danger of being swallowed up by the sand of the Sahara. Every year the desert moves around ten meters closer to the city. In order to save the city, Timbuktu was placed on the list of endangered places of the world cultural heritage by UNESCO in 1990. "

- ↑ Brockhaus 14th edition, Vol. 15, 1908.

- ↑ Average climatic values for Timbuktu

- ↑ Basically René Gardi: You can also live in a clay house. Traditional building and living in West Africa. Graz 1973.

- ↑ For the architecture see Thomas Krings: Sahelländer. Geography, history, economics, politics . Darmstadt 2006, p. 83 ff.

- ^ Douglas Park: Climate Change, Human Response and the Origins of Urbanism at Prehistoric Timbuktu , PhD Yale University, Department of Anthropology, New Haven 2011 .

- ↑ See James LA Webb: Desert Frontier. Ecological and Economic Chance along the Western Sahel 1600-1850. Madison (Wisc.) 1995, p. 16.

- ↑ John Hunwick describes these numbers as “ grossly inflated ” (German: “immensely inflated”). See Hunwick, Timbuktu & the Songay Empire , p. 9. The Egyptian chroniclers of the 14th and 15th centuries know nothing of such a large entourage. The actual amount of gold carried is highly controversial.

- ↑ Said Hamdun, Noel King (Ed.): Ibn Battuta in Black Africa. London 1975, p. 52 f. The fact that Ibn Battuta, contrary to his custom, does not name a single scholar of high standing in Timbuktu allows the conclusion that the city had not yet achieved the importance as a cultural center that is often ascribed to it for this period.

- ↑ The French archaeologist Raymond Mauny put the population at a maximum of 25,000 people based on aerial archaeological studies. The Malian historian Sékéné Cissoko, however, calculated 100,000. His colleague E. Saad put the population at around 50,000, which is the upper limit of any serious estimate. See Saad: Social History of Timbuktu , p. 27 u. 90. The American Webb assumes a population of 30,000 to 50,000. See James LA Webb: Desert Frontier. P. 16.

- ↑ Whether Timbuktu should be regarded as the most important center of Islamic education in the region is controversial. The British West Africa specialist John Spencer Trimingham took the view that Timbuktu's rank in literature is greatly exaggerated and that Djenné played a greater role as the “center of Negro Islamic learning”. See Trimingham: A History of Islam in West Africa. London / Oxford 1970, p. 98.

- ↑ The date of construction 989 mentioned on various websites refers to the Islamic calendar, not to the Christian year counting. Otherwise the mosque would be older than the city itself.

- ^ Dietrich Rauchberger: Johannes Leo der Afrikaner. His description of the space between the Nile and Niger according to the original text. Wiesbaden 1999, p. 126 u. 140

- ↑ According to Heinrich Barth, the term “arma” goes back to a corruption of the Arabic word “ar-rûma (Christian)” and is supposed to refer to the former Christian mercenaries in al-Mansur's army. See Amador Garcia Diaz (ed.): Andalucia en la curva del Niger . Granada 1987, p. 10 ff.

- ^ Antonio Llaguno: La conquista de Tombuctú. La gran aventura de Yuder Pachá y otros hispanos en el país de los negros. Cordoba 2006.

- ↑ The Sultan's Mercenary Army . The name “arma” is also derived from “ar-ruma” (Romans, i.e. Christians), because some of the troops consisted of (formerly) Christian mercenaries from Spain.

- ^ Harry T. Norris: L'Aménokal K'awa ou l'histoire des Touareg Iwillimmeden . In: Charles-André Julien (Ed.): Les Africains. Vol. 11, Paris 1978, pp. 169-191.

- ↑ The decisive passages of the fatwa are printed in Albert Adu Boahen : Britain, the Sahara and the Western Sudan 1788–1866. London / Oxford 1964.

- ^ Heinrich Barth: The newest relations of the French in Senegal to Timbuktu . In: Journal for General Geography NF 16, 1864, pp. 521-526.

- ↑ Pierre Boilley: Les Touaregs Kel Adagh. Dépendances et révoltes du Soudan français au Mali contemporain. Paris 1999, pp. 119-127.

- ^ Herbert Kaufmann: Economic and social structure of the Iforas-Tuareg. Cologne 1964 p. 218 (phil. Diss.).

- ↑ Leland Hall: Timbuctoo. New York 1928, u. Friedrich Sieburg: African Spring. A travel. Frankfurt a. M. 1938. The latter described the city as “a labyrinth of windowless walls, sunken clay ruins and dead doorways […] Nothing is everywhere, it crouches in all doors, in all courtyards, in all nooks and crannies of this city, which resembles an endless city of tombs . ”( African Spring , p. 243).

- ↑ On the history of the conflict, see the long-term study by Pierre Boilley (dissertation at the Sorbonne): Resume online ( Memento from December 11, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Mali Tuareg separatist rebels end military operations. In: BBC News . April 5, 2012, accessed April 5, 2012 .

- ↑ Mali junta caught between rebels and Ecowas sanctions. In: BBC News . April 2, 2012, accessed April 2, 2012 .

- ↑ Trial for the destruction of cultural property in Timbuktu opened on August 22, 2016 on qantara.de . Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ↑ Attack on world cultural heritage. In: TAZ . January 29, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2013 .

- ↑ Mali fears for its cultural memory. (No longer available online.) In: tagesschau.de . January 29, 2013; Archived from the original on January 29, 2013 ; Retrieved January 29, 2013 .

- ↑ Islamists attack Timbuktu

- ^ Tuareg rebels in Mali hoist the flag in Timbuktu. orf.at, April 1, 2012, accessed April 5, 2012 .

- ↑ Mervin Hiskett: The Development of Islam in West Africa. Harlow, Essex - New York 1984, pp. 154 f.

- ^ Paul Marty: Étude sur l'Islam et les tribus du Soudan. Vol. I: Les Kountas de l'Est, les Bérabiches, les Iguellad. Paris 1920.

- ↑ Charlotte Blum et al. Humphrey Fisher, "Love for Three Oranges, or, The Askiya's Dilemma: The Askiya, al-Maghili and Timbuktu, um 1500 A.D.", Journal of African History 34 (1993), pp. 65-91, spec. P. 79 ff.

- ↑ See above all the homepage of the conservative Jewish KULANU organization, which wants to track down the lost ten tribes of Israel all over the world, kulanu.org , as well as corresponding, completely undocumented pages at the English Wikipedia House of Israel or Igbo Jews .

- ↑ See Arabic ذمي, DMG ḏimmī , fellow guardian; Free non-Muslim subject in Muslim states who is subject to a protection treaty '(see H. Wehr: Arabisches Wörterbuch , Wiesbaden 1968, pp. 280 f.).

- ↑ Ismael Diadié Haïdara, Les Juifs de Tombouctou: Recueil des sources écrites relatives au commerce juif à Tombouctou au XIXe siècle. Bamako 1999 (available in Bayreuth University Library)

- ↑ See Auguste Dupuis-Yacouba: Industries et principales professions des habitants de la région de Tombouctou. Paris 1921, u. Owen White: "The Decivilizing Mission: Auguste Dupuis-Yakouba and French Timbuktu", French Historical Studies 27 (2004), pp. 541-568.

- ↑ ICOMOS evaluation report for the World Heritage Committee, 1981 and 1988 (PDF; 715 kB) i. V. m. the text of the decision

- ↑ Official website for "Tombouctou 2006"

- ↑ "Timbuktu is in shock": Fundamentalists destroy UNESCO World Heritage Site in northern Mali , NZZ, May 6, 2012. Accessed July 5, 2012

- ↑ Mali Islamists attack UNESCO holy site in Timbuktu , Reuters, May 6, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2012

- ↑ Devastated World Heritage Site in Mali: Islamists Mock Unesco , Spiegel Online, July 1, 2012. Accessed July 5, 2012. - dradio.de July 10, 2012 . - to the destruction of the overview of terrorists, militias and fanatics of faith - instrumentalization of the cultural heritage in Mali. Archeology (January 8, 2013)

- ↑ Cf. Isabelle-Constance v. Opalinski “Shots on Civilization” in FAZ from August 20, 2014.

- ↑ According to Ibn Hadjar al-Askalani (around 1440), translated by JM Cuoq (ed.): Recueil des sources arabes concernant l'Afrique occidentale du VIIIe au XVIe siècle. Paris 1975, p. 394.

- ↑ Hunwick: Timbuktu & the Songhay Empire , p. 81. According to Tarikh as-Sudan (ibid.) It was not an isolated case.

- ↑ In this context the manuscript "Ahkam al-shira 'al-yamaniyah wa ma yazharu min hawadith fi al-`alam` inda zuhuriha fi kul sanah (knowledge about the movement of the stars and what one can read from it as a sign every year) “Called from the Mamma Haidara library. In 2003 it was on display in the Library of Congress in Washington. The manuscript was created in 1733 and is a copy of an older text, which, however, does not come from Timbuktu, but presumably from Egypt. There is nothing to indicate that the original of this primarily astrological text comes from the time before Copernicus († May 24, 1543), and it is by no means an anticipation of his astronomical knowledge. See also "Timeless Timbuktu: Library Exhibits Ancient Manuscripts of Mali" (with illustration)

- ↑ J. Hunwick: "The Islamic Manuscript Heritage of Timbuktu" ( Memento of August 8, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (WORD file), p. 6.

- ↑ Please keep in mind that a university library houses around two million titles, but requires multi-storey and extremely stable concrete structures that can carry the enormous weight of the books. These books, however, are 90% smaller and lighter than folios bound in leather and written on thick paper or even parchment. The late medieval Timbuktu could not even have provided the materials for suitable buildings, such as the wood for the skeleton of such a clay construction.