History of Mali

The written history of Mali currently goes back around 150,000 years, while written sources only started with Islamization from the 8th to 11th centuries. The settlement before the beginning of the productive way of life and also for a long time afterwards was extremely dependent on the strongly fluctuating extent of the Sahara . From around 9500 BC. Hunters and gatherers made ceramics , later cattle were domesticated and sheep and goats were imported from West Asia. Around 2000 BC In the south of the country people lived mainly from agriculture, especially from millet and other grass seeds; after 800 BC BC rice was added. In the inland delta of the Niger , an urban culture developed from its own roots around 300 BC. BC, whereby the city of Djenne-Djeno was up to 33 hectares in size, the Dia complex covered about 100 hectares.

Probably since the Phoenicians , then the Romans , Berbers operated a stage trade through the Sahara, which is likely to have intensified with the emergence of the Ghanaian Empire, which cannot be precisely determined . Gold initially played an essential role. Inner-Islamic struggles for direction between Berbers and Arabs brought numerous Muslim refugees to Mali, and at the same time the gold trade is becoming more tangible.

In the 11th to 13th centuries, the region's most influential kings converted to Islam , contradicting the region's alleged military subjugation that justified the slave hunt. The Mali empire , which is also based on local gold mining, became famous . Its gold transactions were so large that they shook the Mediterranean system of coins and thus the trading system. The empire also became one of the most important centers of the Old World, culturally and politically . In the middle of the 14th century, the Songhaire empire made itself independent from Mali and dominated the greater area until 1591.

This supremacy ended with a campaign by Morocco that conquered Gao and Timbuktu and controlled the gold and salt trade for a short time. As a result, the emerging small empires were able to participate less and less in the Trans-Saharan trade, which shifted eastwards. At the same time, the technological, organizational and financial deficit compared to the north and, above all, to those countries that dominated the Atlantic trade continued to grow. With the economic decline, the slave trade increased, driven by both Arabs and the early colonial powers. The lack of state structures in large parts of the country played into the hands of less formal associations, such as the Sufi order , especially the Qādirīya and the Tijānīya , which increasingly controlled trade and intellectual life. ʿUmar Tall , the most important representative of the Tijānīya, began a “holy war” ( jihad ) against his neighbors in 1851 , during which he came into conflict with the French in Senegal . At the same time, however, the judges of Timbuktu, who were skeptical of the new master, gained influence far beyond Mali.

In 1883 French troops occupied Bamako , which only became the center of Mali through the colonial power, and Timbuktu followed in 1894. Behind this expansion was the plan to drive the other colonial powers out of the region, driven by merchants from Bordeaux who were interested in trade in West Africa. In addition to the administrative penetration, which left the local dignitaries in office or played off new ones against the established ones, forts ensured French rule as well as rail and ship connections. The population was induced through taxes, sometimes also through forced labor , to take part in public works and to manufacture products for the international market. However, the corresponding civil rights were withheld from the residents until shortly before independence in 1960.

The state of Mali, like most of the African states in its present form, only emerged as a result of colonial borders. From 1960 to 1991 an initially Marxist-oriented one-party regime ruled there, which was replaced from 1992 by elected governments and a party system. Conflicts with the Tuareg living in the north repeatedly led to uprisings, but it was only the breakup of Libya and the intervention of various terrorist organizations that led to the civil war, in the course of which there was considerable destruction of the world cultural heritage in Timbuktu . In 2013, France intervened on the side of the government, and German soldiers were later added. Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world.

Prehistory and early history

Paleolithic

The Sahara was often drier, but also more rainy for a long time than it is today. So it was a place uninhabitable for humans 325,000 to 290,000 years ago and 280,000 to 225,000 years ago, apart from favorable places such as the Tihodaïne lake on the water-storing Tassili n'Ajjer . In these and other dry phases, the desert expanded several times far north and south; its sand dunes can be found far beyond today's borders of the Sahara. Human traces can only be expected in the rainier green phases. It is possible that anatomically modern humans (also called archaic Homo sapiens ), who perhaps developed in the said isolated phase 300,000 to 200,000 years ago south of the Sahara, already crossed the area, which was rich in water at that time, in the long green phase over 200,000 years ago. Even around 125,000 to 110,000 years ago there was a sufficient network of waterways that allowed numerous animal species to spread northward, followed by human hunters. Huge lakes contributed to this, such as the mega-Lake Chad , which at times comprised over 360,000 km². On the other hand, 70,000 to 58,000 years ago the desert expanded again far to the north and south and thus represented a barrier that was difficult to overcome. Another green phase followed 50,000 to 45,000 years ago.

In Mali, the find situation is less favorable than in the northern neighbors. Excavations at the Ounjougou find complex on the Dogon Plateau near Bandiagara have shown that there has been evidence that hunters and gatherers lived in the region more than 150,000 years ago. Dating back to between 70,000 and 25,000 years ago is certain. The Paleolithic ended very early in Mali because after this section 25,000 to 20,000 years ago there was another extreme dry phase , the Ogolia . When, towards the end of the last glacial period, the tropics expanded 800 km northwards, the Sahara was once again transformed into a fertile savannah landscape .

Neolithic

After the end of the last maximum expansion of the northern ice masses towards the end of the last glacial period , the climate was characterized by much higher humidity than today. The Niger created a huge inland lake in the area around Timbuktu and Araouane, as well as a similarly large lake in Chad . At the same time, savannah landscapes were created and in northern Mali a landscape comparable to that which characterizes the south today. This around 9500 BC The humid phase that began after the Younger Dryas , a cold period after the last glacial period, was around 5000 BC. Chr. Increasingly replaced by an increasingly dry phase.

The Neolithic , the time when people increasingly produced their own food instead of hunting, fishing or collecting it as before, developed during this humid phase. This is usually divided into three sections, which are separated from each other by distinct dry phases. Sorghum and millet were planted and around 8000 BC. Large herds of cattle that were close to the zebus grazed in what is now the Sahara; Sheep and goats were not added until much later from West Asia , while cattle were first domesticated in Africa.

Here appears Ceramics , which was long thought to be a side effect of Neolithization in the earliest Neolithic, ie 9500-7000 v. BC, in the Aïr according to Marianne Cornevin as early as 10,000 BC. Thus, the earliest Neolithic is assigned to the phase of the productive way of life, although no plants were cultivated and no cattle were kept. In Mali, the Ravin de la Mouche site, which belongs here , was dated to an age of 11,400–10,200 years. This site is part of the Ounjougou complex on the Yamé , where all eras since the Upper Paleolithic have left traces and the oldest ceramics in Mali date back to 9400 BC. Was dated. In Ravin de la Mouche , artifacts could date between 9500 and 8500 BC. The site Ravin du Hibou 2 can be dated to 8000 to 7000 BC. After that, where the said oldest ceramic remains were found in the course of a research program that has been running since 1997 in the two gorges, a hiatus between 7000 and 3500 BC occurred . BC because the climate was too unfavorable - even for hunters and gatherers.

The middle Neolithic of the Dogon Plateau can be recognized by gray, bifacial stone tools made from quartzite . The first traces of nomadic cattle breeders can be found (again) around 4000 BC. BC, whereby it was around 3500 BC. The relatively humid climate came to an end. Excavations in Karkarichinkat (2500–1600 BC) and possibly in Village de la Frontière (3590 cal BC) prove this, as well as studies on Lake Fati . The latter existed continuously between 10,430 and 4660 BP as evidenced by layers of mud on its eastern edge. A 16 cm thick layer of sand was dated around 4500 BP, proving that the region dried up around 1000 years later than on the Mauritanian coast. A thousand years later, the dry phase, which apparently had driven nomads from the east to Mali, reached its climax. The northern lakes dried up and the population mostly moved south. The transition from the Neolithic to the Pre-Dogon is still unclear. In Karkarichinkat it became apparent that sheep, cattle and goats were kept, but hunting, gathering and fishing continued to play an important role. It may even be the case that successful pastoralism prevented agriculture from establishing itself for a long time.

The late Neolithic was marked by renewed immigration from the Sahara around 2500 BC. Chr., Which had grown into an enormously spacious desert. This aridization continued and forced further migrations to the south, the approximate course of which can also be archaeologically ascertained. On the basis of ethno-archaeological studies of ceramics, three groups were found that lived around Méma , the Canal de Sonni Ali and Windé Koroji on the border with Mauritania in the period around 2000 BC. Lived. This was proven by ceramic investigations at the Kobadi site (1700 to 1400 BC), the MN25 site near Hassi el Abiod and Kirkissoy near Niamey in Niger (1500 to 1000 BC). Apparently the two groups hiked towards Kirkissoy last. At the latest in the 2nd half of the 2nd millennium BC In BC millet cultivation reached the region at the Varves Ouest site, more precisely the cultivation of pearl millet ( Pennisetum glaucum ), but also wheat and emmer, which were established much earlier in the east of the Sahara, now (again?) Reached Mali. Ecological changes indicate that tillage must have already started in the 3rd millennium. But this phase of agriculture ended around 400 BC. In turn by an extreme drought.

The use of ocher for funerals was common until the 1st millennium, even with animals, as the spectacular find of a horse in the west of the inland delta, in Tell Natamatao (6 km from Thial in the Cercle Tenenkou ) shows, whose bones are with it Ocher had been sprinkled. There are also rock carvings typical of the entire Sahara, in which symbols and animal representations also appear as depictions of people. From the 1st millennium BC Paintings in the Boucle-du-Baoulé National Park (Fanfannyégèné), on the Dogon Plateau and in the Niger River Delta (Aire Soroba).

In Karkarichikat Nord (KN05) and Karkarichinkat Sud (KS05) in the lower Tilemsi Valley, a fossil river valley 70 km north of Gao , it was possible to prove for the first time in eleven women in West Africa south of the Sahara that the teeth were modified there for ritual reasons was in use around 4500-4200 BP, similar to the Maghreb . In contrast to the men, the women show modifications ranging from extractions to filings, so that the teeth are given a pointed shape. A custom that lasted until the 19th century.

It was also found there that the inhabitants of the valley already obtained 85% of their carbon intake from grass seeds, mainly from C4 plants ; this happened either through the consumption of wild plants, such as the wild millet, or through domesticated lamp-cleaning grasses . This was the earliest evidence of agricultural activity and cattle breeding in West Africa (around 2200 cal BP).

The sites of the Dhar-Tichitt tradition in the Méma region, a former river delta west of today's inland delta, also known as the "Dead Delta", belong to the period between 1800 and 800/400 BC. Chr. Their settlements measured between one and eight hectares , but the settlement was not continuous, which may be related to the fact that this region was not suitable for cattle farming during the rainy season. The reason for this was the tsetse fly , which prevented this way of life from expanding southwards for a long time.

In contrast to these cattle breeders, who then drove their herds northwards again, the members of the simultaneous Kobadi tradition, who had lived exclusively from fishing, collecting wild grasses and hunting since the middle of the 2nd millennium at the latest, remained relatively stationary. Both cultures had copper that they brought from Mauritania . At the same time, the different cultures cultivated a lively exchange.

Metal processing

The hunters as well as the cattle breeders and early arable farmers show a local processing of copper for the 1st millennium.

The famous rock paintings, which can be found in large parts of West Africa, were also discovered in Mali in the Ifora Mountains ( Adrar des Ifoghas ). Around the year 2000, more than 50 sites with pictographs and petroglyphs were known there. These rock paintings led to the assumption that metal processing in southern Morocco was brought with them by a population coming from the south, probably from Mali and Mauritania. This happened earlier than previously assumed, i.e. before the 2nd millennium BC. When this technology was adopted by the Iberian Peninsula.

Copper was first brought from Mauritania by the cultures in the Méma region, around in the 1st millennium BC. To be processed into first axes, daggers, arrowheads, but also into bars and jewelry. This happened on site, as found by slag finds. The effects on society, which were very pronounced in the Mediterranean area, are still unclear at the current state of research.

Arable farming has probably been around since 2000 BC at the latest. B.C. in the entire area, such as finds in Dia , Djenne-Djeno , Toguéré Galia, which are all in the Niger Inland Delta, Tellem ( Falaise de Bandiagara ), Tongo Maaré Diabel (Gourna), Windé Koroji West I (Gourna) and Gao Gadei prove. It is believed that the man of Asselar , who was discovered in 1927/28 and of whom the sex is not even considered certain, lived in the Neolithic.

Rice culture in the inland delta, urban culture from its own roots (800/300 BC – 1400 AD)

Around 800 to 400 BC In Dia, agriculture was based on domesticated rice ( Oryza glaberrima ), a plant that was more important than other species such as millet for the cultivation of the humid Niger region during this period . At the same time, this area was probably the first in which rice was cultivated in West Africa. The first confirmed finds come from Djenne-Djeno (300 BC - 300 AD). In addition, wild grass was still harvested, especially millet .

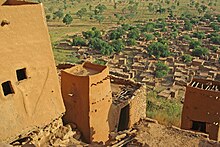

The first cities appeared in the inland delta of the Niger from around 300 BC. In addition to Djenne-Djeno, Dia stands out, lying northwest of it, across the river. Around this early city, which actually consisted of two settlements and a tell, there were more than 100 villages that were located on former and still existing tributaries of the Niger. Similar structures emerged around Timbuktu and Gourma-Rharous further downstream. In Wadi El-Ahmar north of Timbuktu, for example, a paleo canal that was regularly fed by the floods of the Niger was found, a 24-hectare site that was surrounded by nine such “satellites”.

The north of the country has been drying since around 1000 BC. And the nomads were forced to retreat to the mountainous areas, which still offered water, or to move south. Between 200 and 100 BC The north of Mali became extremely dry. The groups living in the north were not replaced by Berber and Tuareg groups until the 11th and 12th centuries AD .

The oldest finds in the Djenne-Djeno (also Jenné-Jeno) excavated from 1974 to 1998 in the inland delta were dated to around 250 BC. BC and thus prove the existence of a differentiated urban culture from its own roots. In Djenne-Djeno, as in the entire inland delta, iron and copper were already being used from the first millennium BC. Processed. The next iron ore deposit was near Bénédougou, around 75 km southwest of Djenne-Djeno. Two Roman or Hellenistic pearls indicate trans-Saharan trade, but otherwise no influences from the Mediterranean are recognizable, so that you have to reckon with numerous middlemen when trading and barter. By 450 the city had already reached an area of 25 hectares and grew by 850 to 33 hectares. It was surrounded by a 3.6 km long wall. The houses were mostly made of cylindrical, sun-burned bricks that were in use until the 1930s. At the same time, rectangular bricks were already being used, albeit to a lesser extent.

But around 500 the structure of society changed, because now there were organized cemeteries with burials in large vessels - mostly ceramics previously used as storage vessels - inside, and simple burials in pits on the edge or outside of the city. Around 800 there were their own blacksmiths at fixed locations, so that one reckons with a box-like organization of this craft. In the meantime the city had merged with the neighboring Hambarketolo to form a complex that covered 41 hectares.

In the 9th century there was a drastic change, because the previous round houses were replaced by cylindrical brick architecture - first recognizable by the 3.7 m thick city wall at the base - and the painted ceramics were replaced by stamped and engraved ones. About 60 archaeological sites within a radius of only four kilometers are known around Djenné , many of which flourished around 800 to 1000. However, while the area of the villages was up to 2.9 and 5.8 hectares before the 8th century, afterwards they only reached an area of 1.2 hectares. In the early phase, the distance between the metropolises such as Djenné- Djeno or the Dia complex was particularly large, because the former comprised 33 hectares, the latter even 100 hectares.

The previously dominant city shrank in favor of Djenné around 1200 and was even given up around 1400. This was perhaps related to the predominance of Islam, but at the same time areas in the north were abandoned due to increasing drought, so that many people moved south. This may have caused severe political shocks.

It was not until the 11th and 12th centuries that Islam increased its influence, initially through the reviving Trans-Saharan trade. Archaeologically, these changes are reflected in the form of brass instruments, spindle whorls and rectangular instead of round houses. Traditionally it is believed that King (or Koi) Konboro of Djenné converted to Islam around 1180. The clearest sign, however, are the foundations of three mosques, especially at site 99.

Trans-Saharan trade between Berbers and Jews

In the time of the Romans , it is said again and again that Berber merchants operated a stage trade on the Trans-Sahara routes south of Morocco via the area of what later became Mauritania to the middle Niger and Lake Chad , taking the culture of the local population noticeably influenced. John T. Swanson traced the origin of this “myth” in 1975, who on the one hand used the similarity of the trade route from the Nile to Timbuktu as an argument for such a trade from the 5th century BC onwards. . Based AD that Herodotus in his description Libyas called in Book IV. On the other hand, the growing volume of gold coinage in the Roman Empire between around 100 and 700 AD was cited in favor of a trans-Saharan gold trade, as well as the sheer size of the Mediterranean cities of North Africa, which could not seem to be explained without such intensive trade into the Sahel. This trade was therefore diminished by the invasion of the Vandals in North Africa and recovered after the reconquest by Eastern Current. But the few finds are insufficient to prove such intensive trade. The increasing drought and thus the length of the distances to be overcome could nevertheless have favored the introduction of a new riding and carrying animal, the camel , in the centuries before the turn of the century. Horses and donkeys were no longer able to cope with the extreme climate.

A deep split in Islam - in addition to the one between Sunnis and Shiites - which was connected with the prominent position of the Arabs, since they had produced the Prophet Mohammed , proved to be particularly beneficial . Because the peoples who soon became Islamic as well, such as the Berbers, in some cases vehemently rejected this priority. Therefore, the Berbers in the Maghreb supporters of egalitarian overlooking the successor as caliph flow of were Kharijites , all Muslims regarded as equal. The Kharijites had segregated themselves in 657 because they did not recognize the process of determining the successor to the founder of the religion, Mohammed. Anyone could lead the Muslim community, the umma , for them. When the Orthodox Abbasids tried to suppress this movement with massive violence, this brought many refugees to the Kharijite ruled areas in the Maghreb, which in turn soon promoted trade to the south. In the Maghreb, uprisings began around 740, and in 757 the Kharijites found refuge in Sidschilmasa , which until the middle of the 11th century dominated the Trans-Saharan trade towards Niger and Senegal, perhaps even only established it.

Following the Islamic-Arab expansion in North Africa until the end of the 7th century and a period of relative peace around 800, the previous stage trade was transformed into a continuous caravan trade of the Berbers and Jews from the northern to the southern edge of the Sahara. The overriding Berber group in the north were the lamtuna , in turn, the large group of Sanhaja dominated, so that the main trade route between Sidschilmassa and NUL in the Anti Atlas at one and Aoudaghost in Mali at the other end as "Lamtuni Route" (Tariq Lamtũnī) referred to was . At the same time, the Kharijite Sidjilmassa was at the end of the trade route across the Touat , which ran further to the east.

The boom in trans-Saharan trade in this form, however, presupposed the existence of structured empires south of the Sahara that would guarantee the political order.

Great empires (around 600–1591) and their Islamization (11th – 13th centuries), Dogon

Ghana Empire of the Soninke (4th century (?) To around 1200)

From the Soninke groups in the upper Niger and Senegal regions , the kingdom of Ghana may have emerged as early as the 4th century , known locally as Wagadu , but known to Arab authors as Aoukar . However, hardly anything can be considered certain over the first centuries of this empire. It was first mentioned around 773/774 by the astronomer and mathematician Muhammad al-Fazari , who lived in Baghdad , the capital of the Abbasids , and who called it the "land of gold". For Ibn Hauqal (977) the "King of Ghana was the richest king on earth", his dogs wore golden bells. A more detailed description of the country can only be found from the 11th century in El Bekri , who, however, did not get there himself, but had interviewed travelers. At that time, Ghana controlled the Aoudaghost trade . His power ranged from upper Senegal in the west to upper Niger in the east. It probably reached its zenith in the 11th century.

The kingdom of Ghana is believed to have been based almost exclusively on the exercise of rule by the king and his followers. There was no administrative system and central facilities such as would appear in the later empires of Mali and Songhai . Like all other empires in the region, this one based its wealth essentially on the trade in gold and ivory from West Africa to the Mediterranean and the Middle East. Also, copper , cotton , tools and swords (first from Arabia , and later also from Germany), horses from Morocco and Egypt Kola nuts and slaves from the southern West Africa passed this area, as well as salt. The gold came first from Bambouk , later from Bouré .

The downfall of Ghana is not clear. It coincides with the expansion of the Almoravids , who conquered the trading hub Aoudaghost in 1054. With their herds they also caused an ecological catastrophe in the vulnerable area, which was possibly the cause of the breakup of Ghana. In any case, the Almoravids now controlled the Trans-Saharan trade and ensured a surge in Islamization in the sense of a more fundamentalist doctrine.

A long and widely accepted hypothesis was that the Almoravids conquered the capital of the Ghana Empire in 1076, forced the pagan population to convert to Islam, and ruled the country for two decades. This news is based on the much later information from Al-Zuhari († between 1154 and 1162) and Ibn Chaldūn († 1406) and is now in doubt. According to Pekka Masonen and Humphrey Fisher, the news of the conquest by the Almoravids goes back to Leo Africanus . Although this by no means asserts an Almoravid conquest, such an assumption gradually came together. The starting point was the Spanish chronicler Luis del Mármol Carvajal , who in 1573/99 took over the descriptions, including Leo's contempt for black culture. He was the only one to add that the Lamtuna Berbers had conquered Timbuktu. After him, the Almoravids ruled over already Islamized inhabitants. Possibly this Almoravid southern expansion should provide the historical model for the campaign of the Moroccan ruler of 1591, in which he actually had Timbuktu conquered. Contemporaries of Mármol from Touat in Northern Sahara , who were concerned about having enslaved blacks who had voluntarily converted to Islam - which was strictly forbidden - asked a local lawyer in Timbuktu whether these blacks had been subjugated militarily by Muslim rulers, and only afterwards be converted. In this forced case, even adopting the new religion would never again have protected from slavery. The interviewee, Ahmad Baba from Timbuktu, replied that while infidel blacks were lawfully enslaved, the Muslim blacks of Sudan were never subjected before conversion. So they had converted to Islam voluntarily. The motives on both sides remain unclear. It is possible that Ahmad Baba wanted to protect Muslim blacks from enslavement by their co-religionists, but the counter-argument can also be interpreted in such a way that it had to be in the interests of the slave traders to have free rein. In any case, the version of the slave traders prevailed in Europe, as Francis Moore, an English slave trader wrote in Gambia in 1738. In the middle of the 19th century, the Almoravid subjugation of pagan blacks was considered certain, some of whom it was even assumed that they had previously been Christians. In contrast to the British, German historiography did not yet know this version. Neither Johann Eduard Wappäus nor Friedrich Kunstmann mention a conquest in 1076.

Another argument against the alleged conquest of 1076 is that the capital of the Ghana Empire was not conquered by the army of Soso until shortly after 1200 . But this message, also passed down by Ibn Chaldūn, led to the assumption that the Susu Guineas had destroyed the city. But this error is based only on the aural similarity of the two names. In fact, the name of the conquering empire goes back to the place Soso between Goumba and Bamako, which made itself independent of the Ghana Empire at the end of the 11th century. Around 1180 a family belonging to the armory caste succeeded in usurping power. Under the magician and general Sumanguru Kannt, the residence of the former overlord was finally conquered. Finally, in 1240 Sundiata Keïta , the first mansa (king) of the Mali Empire, destroyed the city and occupied Ghana after he was defeated by Sumanguru in 1235.

In particular, very little is known about this capital city. A city called Ghana near today's Koumbi Saleh , 200 km north of Bamako, was considered the residence of the lord of the Ghana Empire . But Abū ʿUbaid al-Bakrī narrates in 1067/68 that this city actually consisted of two cities, between which dense settlements developed. The king resided in El-Ghaba . In the other city, the name of which has not been passed down, Muslim Arabs and Berbers are said to have lived.

The question of the conversion to Islam by the kings of Ghana has not yet been finally clarified. In any case, around 1009 the Songhai king Dia Kossoi converted to Islam when his capital was moved from Kukiya to Gao . Takrur on Senegal followed around 1040, and finally Kanem around 1085. The conversion was comparatively peaceful in the early phase, while at the same time the military power of the Almoravids in 1071 violently enforced Sunniism against the Kharijites. It was only with the connection to the Islamized world, which was deeply characterized by the use of writing, that there was a growing need for books in Mali, which rose to become an extremely important commodity. After the conquest by the Almoravids, the previous sacred kingship gradually lost its rulership function in the course of the Islamization process.

Dogon culture

The Dogon culture developed quite differently from the great empires . If one follows the oral tradition, their culture originated on the up to 500 m high and 150 km long Bandiagara cliffs , which were declared a World Heritage Site in 1989 , between the 8th and 15th centuries. According to Christopher D. Roy, the Dogon lived in northwest Burkina Faso until 1480 . Their culture was borne by the Mandinka , various groups of the Gur languages and Songhai , but repeatedly suffered from raids by the Fulbe , Bambara and Mossi . This was due to the fact that according to Islamic principles they could be enslaved as non-believers. Today more than 400,000 of them live in the cercles Koro , Bankass , Bandiagara and Douentza . Some of them have converted to Islam.

Mali Empire of the Malinke, Islamization (around 1230)

The Mali Empire emerged from the Kangaba Empire on the upper Niger, east of Fouta Djallon in Guinea. The local Mandinka or Malinke , who operated the trans- Saharan gold trade, rebelled against the Susu chief Sumanguru under Sundiata Keïtas around 1230 . Sundiata Keita, the brother of the expelled ruler of Kangaba, became mansa (king) and converted to Islam. At that time the name Kangaba was replaced by the name Mali. The conversion to Islam represented on the one hand a gesture of friendship towards the trading partners in the north, on the other hand it also used the advantages of efficiency and organization that an alliance with this religion brought with it. Nevertheless, Sundiata owed its political success just as much to the exploitation of traditional beliefs as that of Islam, but also to the fact that the Mandinka were the most successful cultivators of the Gambia and Casamance rivers . Sundiata succeeded in subjugating the gold mines in Bondu and Bambouk in the south, from Jarra in the Gambia, and penetrated along the Niger to Lake Débo in the center of present-day Mali.

The new empire with the capital Niani reached its greatest area under Mansa Musa (1307 / 1312-1337) when it stretched from the Atlantic to the border of today's Nigeria . Mansa Musa ruled Timbuktu and Gao, extended his power to the southeast Mauritanian Walata and to Taghaza , which was 800 km north of Timbuktu. With this he gained control over the salt obtained there, but also over the trade with the southern Moroccan Sidschilmassa. In the east the Hausa there were subjugated, in the west his armies attacked Takrur and the lands of the Fulbe and Tukulor . At this time, the Trans-Saharan trade reached its peak, with Mali's traders becoming known as Dyula or Wangara . Mansa Mussa sent envoys to Morocco and Egypt. The empire under Mansa Musa was so prosperous that when this ruler came through Egypt on a pilgrimage to Mecca , the currency there - the gold-based Egyptian dinar - collapsed for years due to his lavish gold gifts. Musa brought perhaps ten tons of gold onto the market, so that in Venice, the hub of gold and silver trade, the value ratio of the two precious metals suddenly rose from 1 to 20 (1340) to 1 to 11 (1342), and finally to 1 by 1350 9.4 collapsed. The value of gold in relation to silver fell until, probably in the 1370s, a complete demolition of the gold caravans ended the influx. The death of Sulayman (Mansa Musa's brother and successor) and the following arguments led to the collapse of the empire and brought the complicated trans-Saharan (gold) trade network to a collapse.

Musa's reign represented a period of stability and prosperity, and it was during this period that Timbuktu and Djenné began to rise to become centers of education and cultural prosperity. Musa brought architects from Arabia to build new mosques in these cities, and he improved the administration by building them more methodically. The actual beginning of a state administration, however, only came with the rise of the Songhai . What was remarkable was the strong influence that slaves, as royal administrators, exerted on the government at times in the Mali Empire.

The area in which Mali and, to a lesser extent, Niger and Senegal are located today , formed one of the most important trading centers in the entire Islamic world. Some of its trading cities - Djenné, Timbuktu and Gao in particular - have become known as centers of wealth and cultural splendor, and are surrounded by a mysticism that has persisted over the centuries to this day. Others, such as Kumbi and Aoudaghost, which were no less famous at the time, are now only in ruins on the edge of the Sahara.

The rise of these cities is due in no small part to the spread of Islam, which in those days became the religion of commerce. Throughout this period, the respective traditional beliefs remained of crucial importance and have been preserved to this day among tribes such as the Dogon, Songhai and Mossi.

The wealth of the trading cities was primarily based on the taxes levied on gold shipments from West Africa to North Africa and the Middle East and on the caravan trade in salt from the Sahara oases to West Africa. The gold from West Africa was so important that the use of this metal as a means of payment in the Mediterranean area would have been inconceivable without this source. Even the monarchs in England had their coins made from gold, which came from West Africa.

The decline of the Mali Empire began soon after the middle of the 14th century and continued increasingly in the first half of the 15th century. In 1362 the Tuareg conquered Sidschilmassa, the king of Mali was forced to sell his most valuable gold reserves in 1373/74, including a huge nugget weighing 30 pounds. Gao rebelled around 1400, the Tuareg conquered Walata and Timbuktu, which was taken without a fight in 1433. Takrur and his neighbors, especially the Wolof , threw off Mali's supremacy and the Mossi in today's Burkina Faso massively disrupted trade. By 1550, Mali no longer played a political role.

Songhai Empire (1335–1591)

The Songhai maintained markets in Kukiya near today's village of Bentia and Gao around 600 and founded their own territory around 670. There were trade contacts with the Berbers of Tadmekka in the Iforas Mountains, so that the Songhai could benefit from the salt trade.

Although they were originally vassals of Mansa Musa , by 1375 they had built up a strong city-state with a center in Gao and were able to shake off Malian supremacy and themselves to continue the imperial tradition of Western Sudan. However, the fighting between the Tadmekka Berbers and Mali was so intense that the city had to be abandoned between 1374 and 1377. In the middle of the 15th century, the Songhai were strong enough to penetrate into the Niger Lake District and Djenné , and in 1464, under the leadership of Sunni Ali Ber, they finally set out to conquer the Sahel region to succeed the weakened Mali Empire to compete. In 1468 they conquered Timbuktu, which prospered economically and culturally.

The last century of the empire was dominated by the Askia dynasty, overthrowing the Za dynasty in 1492, which had ruled since the 7th century. After Askia Mohamed Toure , endowed with the right to act as the caliph of Islam in western Sudan , returned from his pilgrimage to Mecca, he sent his army in the west to the Atlantic coast and in the east to the borders of the Hausa states . Then the Songhai army conquered the oases of Aïr and settled there - in the fortress of the Tuareg - groups of Songhai whose descendants still live there today. Askia Daoud (1549–1583) is considered the most important Songhai ruler.

Like the Mali rulers, the Songhai rulers converted to Islam, but at the same time they were careful to maintain a balance between the local state tradition and Islam. Compared with the Mali empire, the center of the Songhai empire lay further to the northeast on the middle course of the Niger. From this core area, its expansion also took place over large parts of the Sahara, so that its expansion exceeded that of the Mali Empire.

The power of the early Songhai rulers was initially based on the rural peasants, but the Muslim-dominated urban elites gradually played an increasingly important role. Herein lay the decisive weakness of the empires of this region, because such an arrangement only worked as long as the rulers did not give up their original power base of the sacred pre-Islamic state in favor of Islamization and the Islamic state doctrine.

Muhammad al-Maghīlī († around 1505), who had already had the synagogue in Tlemcen , Algeria , destroyed and who had fought the Jewish Berbers in Touat, Algeria (probably 1492), went to Timbuktu because his undertakings were rejected by the Muslim rulers. But he also taught in Takidda, Kano, the Emirate of Katsina and in Gao with the Songhai, whose rulers on his initiative prohibited Jews from entering their empire.

Moroccan invasion (1591), role of Sufism, kingdoms (until 1893)

Ahmad al-Mansur , Sultan of Morocco from 1578, demanded a levy of one mithqal of gold on every single cargo of salt that left the Taghaza mines for the maintenance of the Islamic army (against the Portuguese) from Askia Daoud . Instead, he sent the Sultan a gift of 10,000 mithqal gold, which is likely to have been more than 22 kg. Askia Ishaq († 1549) had his riders plundered a village south of Marrakech without killing anyone to demonstrate his power. Al-Mansur conquered the salt mines in 1585, but the Songhai soon took them back.

But al-Mansur, who saw himself as harassed by the Portuguese, who had already contacted Timbuktu via Senegal in 1565 and who had tried to conquer Morocco in 1578, as he was by the Ottomans , who attacked his empire from Algiers , saw himself forced to pursue his ambitions. In addition, Moroccans occupied Touat and Gurara in 1582, and in 1583 the sultan managed to get Bornu recognition as caliph. The king there saw himself threatened by the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. With this the preparations for far-reaching conquests were completed, but a first attempt to advance to Senegal failed for unknown reasons. Al-Mansur's army, which finally set out from Marrakech on October 30, 1590, met an empire weakened by dynastic fighting after the death of Askia Daoud, which was also badly shaken by an epidemic in 1582 and by a famine in 1586. Askia Ishaq II., A son of Daoud, succeeded his brother Askia Mohammed Bani in 1588. This, in turn, died in a campaign to the west, because there Mohammed el-Sidiq had declared himself independent and proclaimed Askia.

On March 1, 1591, in this situation, a Moroccan army led by Djouders encountered the Niger and reached Tondibi eleven days later, 50 km from Gao. Ishaq II, who with his 18,000 riders and 9,000 foot soldiers was defeated by the only 4,000 muskets armed Moroccans at Tondibi , Djouder made an offer of peace, which Djouder accepted. But the Moroccan sultan refused negotiations and instead sent Pascha Mahmoud b. Zarkun, who reached Timbuktu on August 17, 1591. He defeated the Songhai on October 14, 1591 at Zenzen near Bamba . Ishaq II was replaced by his brother Mohammed Gao, Ishaq fled to Burkina Faso, where he was murdered along with his supporters in March and April 1592. However, Askia Nouh, another son of Askia Daoud, fought the conquerors in a guerrilla war lasting several years. However, he first had to retreat to the province of Dendi southeast of Gao, where he held the remnants of his rule together until 1599. He was replaced that year by his brother Moustapha, who was followed by other rulers. In 1594 Mahmoud was killed in a battle and Djoudar should now again complete the conquest, which was not possible in view of the resistance of the Fulbe, Bambara and Manden under Askia Mahmoud. Ultimately, the Moroccans could only hold on to a few forts along the Niger between Djenné and Timbuktu. The Moroccan pashas did not interfere in the appointment of local imams, kadis or local rulers, even if the candidates had to be presented to them. From 1599 the Christian legionaries who served in the Moroccan army were sent back to Marrakech, while al-Mansur sent groups that he wanted to remove from Morocco anyway to the Niger. These included three Guish strains (these were artificially created by the first Saadians tribes, exempt from charges or had been provided with land) that haha (south of Essaouira ), the Ma'kil (Arabs, originally from the Yemen came ) and the equally Arabic Djusham.

The weakness of the Songhai and the distance of Morocco strengthened the position of the judges of Timbuktue and Djenné, where these kadis had already held an important position before the Askia rulers.

The success of the Moroccan army was mainly based on the technical superiority of the conquerors, who wanted above all to bring the salt and gold trade under their control, after the Sultan had no resounding successes against the Portuguese, who established themselves permanently on the Atlantic coast. While most of the ruling elite surrendered to the Moroccan invaders and obeyed a shadow king in Timbuktu, a number of successive rival kings resisted the Moroccans for decades. The intellectuals of Timbuktu such as Aḥmad Bābā (1556–1627) had to go into exile in Marrakech, as did entire libraries like the royal library of Gao. In the end, the Moroccan Sahara trade was so damaged that it shifted eastwards to Tripoli and Tunis , especially since the empire split into different domains from 1603 onwards. In 1604 the last Moroccan Pasha Mahmoud Longo appeared with 300 men.

In the meantime, gold and salt were no longer the dominant trade, but the slave trade. The Saadians of Morocco had already invested in this trade before 1591, as they needed the slaves for hydraulic engineering work to extract sugar. But at the beginning of the 17th century this attempt to build up a sugar industry in southern Morocco collapsed because the Portuguese in Brazil were considerably more successful in this.

But with the resurgence of Morocco from the 1660s onwards, Morocco shifted to an army of slaves, so that the Trans-Saharan trade saw this as its “main trade good” again. At first the sultan contented himself with the enslavement of the black Ḥarãtĩn living in Morocco , but after complaints by Muslim scholars he switched to the southern tribes, who went on raids as far as Senegal, and to the slave market of Timbuktu. But this system of a slave army collapsed with the death of Mulai Ismail after 1727.

Empire of the Bambara

The advance of the Moroccans, the shift of Saharan trade to the east and transatlantic trade led to a drastic loss of importance for Mali and the whole of West Africa, even if individual caravan routes continued to operate. The religious importance of the big cities as centers of state-supporting Islam also declined. In addition, the dependence of the economically and territorially growing European states on West African gold was severely broken through the exploitation of overseas mines. In addition, the barbarian states under the control of the Ottoman Empire increasingly formed a trade barrier. As a result, West Africa suffered from severe isolation from the Mediterranean world.

After 1660, the Bambara established a state in the Ségou region, which had its heyday under Biton Kulibali (1712–1755). He was not a Muslim himself, but his son Bakary was raised by Muslim scholars. As he succeeded his father, that influence increased.

Biton Kulibali handed over to the former slave Ngolo Diara the position of "guardian of the four cults of Ségou". He succeeded in seizing power in 1753 and establishing the independent Bambara empire of Kaarta in western Mali. Like his predecessors who did not convert to Islam, he tried to balance the religions. Although he followed Islamic rites, at the same time he remained a priest of protective idols, because the Bambara remained true to their traditions. Nevertheless, the rulers culturally distanced themselves more and more clearly from their subjects, so that Islam was increasingly used as an ideology of rule. Nioro du Sahel became the capital of the empire.

In contrast to ethnic groups and states, religious groups, such as the followers of Sufism , were able to participate in trade without any direct structures of rule. They founded schools and imported paper from Europe for their writing supplies, as did books. The al-Kunti sheiks of Timbuktu created numerous works between 1760 and 1870. The Sufi orders or brotherhoods, initially the Qādiriyya, gained a lot of influence, also in Timbuktu. This was especially true of the Kunti, who traced back to Arab roots. At the end of the 18th century, the Tijānīya emerged in Fez , which also increasingly controlled trade routes. The best known were the Sanusiya from the Cyrenaica, who ruled this region from 1843, but without interfering directly with the trade.

1861 Segou fell jihad of Umar Tall victim to a Sufi Tijaniyyah , who was defeated in 1857 by French troops, although -Ordens, but now the cost of the kingdom of Bambara extended his empire to the east. However, in 1864 he was beaten by the Bambara and murdered shortly afterwards. However, the Tijānīya and some branches of the Qādiriyya should rather support the colonial arrangements in the Sahel, while the Libyan and Algerian Sufi brotherhoods took the lead in the resistance.

Sufism and jihad empires between the colonial powers, "heretics"

Amadu Hammadi Bubu attempted to establish the Massina Empire at the beginning of the 19th century . To this end, he declared a jihad in 1818 and founded an empire around Mopti . He then conquered Timbuktu and Djenné in 1819, where he had the great mosque from the 13th century destroyed around 1830.

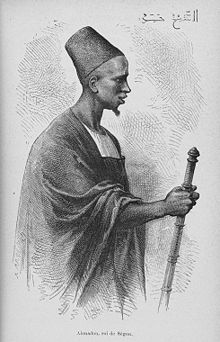

But a branch of a Sufi order that originated in Morocco turned against his kind of political and religious dominance. Its most important advocate, ʿUmar Tall , born around 1797 in southern Senegal, came from a family with an Arab education. In 1820 he went on pilgrimage to Mecca and returned with a mandate to found a caliphate for the Tijaniya Sufis. The ruler of Sokoto gave him two of his daughters as wives. In 1850 he founded his own state in Dingiraye , now called El Hajj Omar . In 1851 he started a jihad against non-Muslim and Muslim neighbors whom he considered "pagan". In the early 1850s he attacked the Kingdom of Kaarta , forced its conversion to Islam and had a large mosque built in the capital Nioro in 1854. In the 1920s, Nioro became the center of the Hamālīya, a branch of the Tijānīya that was quickly viewed as heretical. In 1936 the followers of the order changed their qibla and from then on prayed towards Nioro, which they called their Mecca. In 1854 ʿUmar Tall turned against the French Senegal colony, but in 1857 he failed at the Medina fortress. In 1861 ʿUmar Tall turned towards Ségou, where he moved in on March 10, 1861. In 1861 he conquered the Islamic Fouta Toro on the lower reaches of Senegal and on March 16, 1862 occupied Hamdullahi , the capital of the empire of Massina in the Niger inland delta, which was shaped by the Qādirīya order , which the conqueror accused of " apostasy ". Its Fulbe ruler had also proclaimed himself Amīr al-Mu'minīn ( ruler of the believers ).

However, ʿUmar Tall did not succeed in pacifying the Bambara and Fulbe who rejected his regiment. After his murder, his son and successor Amadou took over rule in 1863, but he came into conflict with France, which expanded its colonial empire to the region in 1891. In 1884 he had already left Ségou and handed the city over to his son Madani, but French troops occupied the city in 1888. Amadou fled to Sokoto in Nigeria in 1892 , where he died around 1898. France founded a colony on June 16, 1895, from its previously unrelated conquests.

The Tijānīya brotherhood in Mauritania and Niger had clashed with the influential Qadiriyya , especially with the ulama (Koran scholars) from the clan of al-Baqqā'ī in Timbuktu, who were considered to be the highest authorities in theological and legal questions among the Kunta . Before the French conquest, there were disputes over the interpretation of Koranic regulations for everyday life and disputes with other Sufi orders. Both orders, like the clans behind them, are of great importance to this day. The ʿUmarīya, founded by Umar Tall, is one of the two oldest branches of the Tijānīya order. It was headed from 1984 to 2001 by the reformist scholar Ahmad Tidschānī Bā. He came from Mali and was a descendant of ʿUmar Tall.

Sidi Ahmad al-Baqqai , a kunta from the Mabruk oasis in the Azawad region, north of Timbuktu, came from a clan that had been in constant conflict with the emirs, later caliphs of Massina , since the conquest of Timbuktu by the Fulbe in 1820 , who also claimed the rank of religious leader. When the Briton Alexander Gordon Laing arrived in Timbuktu in 1826 , Sidi Muhammad al-Mukhtar protected him from fundamentalists there. He died shortly after Laing's murder. In 1847 Ahmad al-Baqqai succeeded his brother as Lord of Timbuktu. Most of his extensive library was lost when his son fled to the Tuareg of the Ahaggar Mountains after the occupation of Timbuktu by the French (1895/96) . In the disputes between the Kunta and Tuareg, he appeared as a mediator. The Frenchman Henri Duveyrier , who visited the Tuareg in southern Libya around 1860, reports that al-Baqqai's reputation even extends to Tassili n'Ajjer . In many questions of religion and justice he was respected by the Koran scholars of the northern Tuareg.

Al-Baqqai also became known in Europe when he placed the German Heinrich Barth , who came to Timbuktu in September 1853, under his protection. This led to an open conflict with the overlord of the city. Al-Baqqai turned against his order to drive out or kill Barth, because in his eyes the order violated the principles of Islam. He also denied the ruler the rank of caliph; on the contrary, he and his councilors had to seek the judgment of the chief Koran scholar of Timbuktu on spiritual and legal questions. Barth and al-Baqqai, who had an extensive dialogue in Arabic about theological literature, signed a treaty in which Britain undertook to give the Tuareg and Timbuktus sovereignty to the French, who were advancing from Algeria and Senegal against the Niger knee protect.

Colonial period: 1883–1960

The transition to the colonial era was significantly influenced by climatic changes. The Sahel was also exposed to strong fluctuations in the amount of rain before and during the colonial period, which in this area, which is difficult for arable farming and cattle breeding, led to violent fluctuations in the number of people and to massive emigration and immigration. While from 1870 to 1880 comparatively rich rainfall of an estimated 500 mm per year favored good harvests, the rainfall fell from around 1895 and between 1910 and 1920 there was a severe drought. The submission to French colonial rule fell accordingly in a phase of increasing drought with correspondingly poorer harvests and problems for the cattle farmers. This drought eased after 1920 and somewhat richer rains marked the years up to 1950, even if they no longer reached the level of the 19th century. Another drought followed from the mid-1960s, although the average rainfall between 1961 and 1990 stabilized at around 371 mm per year. However, the drought did not affect the entire Sahel, because in a few years rainfall even increased in the north-west. In addition to the climatic fluctuations, there were military conflicts triggered by the expanding colonial power of France.

French conquest (1883–1898)

French troops occupied Bamako in 1883. Amadu Schechu stuck to his anti-French course for a long time, but in 1890 and 1891 the French commander Louis Archinard occupied Ségou and Nioro and drove the ʿUmarians who had immigrated from the Fouta Toro out of Kaarta. Bandiagara , the last fortress of Amadu Schechu, fell in 1893. While Archinard now enthroned Agibu as the new “King of Massina ”, Amadu and his followers performed the hijra in the areas near Niamey that were still under Muslim rule . Some returned to Bandiagara in 1894/95 and came to terms with the colonial power, others emigrated to Hausaland in 1897 .

In 1894 the French finally subjugated Timbuktu through General Joseph Joffre . In the south, the resistance to the occupation was mainly led by the Malinke Samory Touré . However, it mainly affected the southern neighboring areas. This resistance did not end until 1898.

The architect of the colonial empire in West Africa is Louis Léon César Faidherbe , who resided in Saint-Louis in Senegal from 1854 to 1861 and from 1863 to 1865. His plan was supported by a colony that stretched from the Atlantic to the Red Sea, merchants from Bordeaux, who worked as a lobby group in order to receive political and military support from the French state. After the ban on the slave trade, their trade concentrated on gum arabic , which was soon protected by coastal forts and sealed off from domestic competition. In 1863 Faidherbe sent Abdou-Eugène Mage to Amadou with the request to allow gunboats on the Niger, and to build forts as far as the Bamako area. Amadou held Mage in the country for two years and signed a trade treaty against arms deliveries.

Faidherbe's successor, Louis-Alexandre Brière de l'Isle, however, focused more on the connection between Senegal and Algeria between 1876 and 1881. To this end, a rail link was to be created between the navigable sections of Senegal and Niger. He also sent an emissary to Amadou who concluded protection treaties with local potentates on the way. Joseph Simon Gallieni stayed in Nango on the outskirts of Ségou from June 1880 to March 1881. But the French government never ratified the Treaty of Nango and Amadou Tall complained that its Arabic version of the text never provided for a protectorate of France. De l'Isle established a military district on Senegal, the commander of which, Gustave Borgnis-Debordes, moved eastward from his residence in Médine and occupied Bamako in February 1883. In the same year the gunboat Niger was brought overland from Médine to Koulikoro, from where it sailed across the river to Diafarabé east of Ségou.

The occupation of today's Mali was carried out by Gallieni and Louis Archinard. In 1887 Gallieni's troops attacked Mamadou Lamine Dramé, a nationalist Soninke leader who had established a state in western Mali and eastern Guinea and Senegal. Dramé called for jihad against both the French and Amadou Tall, which led the latter to form an alliance with the French. In May 1887 he signed the Treaty of Gouri, which provided for a French protectorate. In connection with a contract with Samory Touré in Senegal, France succeeded in cutting off the British of Sierra Leone the way to their own expansion. Following the example of a school in Senegal, which Faidherbe had founded in 1857, schools for the children of the local leadership groups were built in western Mali. Villages de liberté (freedom villages) were created for former slaves and refugees from local wars. In 1888 the railway had reached Bafoulabé .

Under Gallieni's successor Louis Archinard, who occupied the area between Kayes and Bandiagara, Ségou was occupied in 1890; Massina and Bandiagara followed in 1893. His successor Eugène Bonnier initiated a campaign against Timbuktu against the will of the governor of French Sudan.

The occupied territories were divided into administrative units, the cercles , which were headed by a comandant . This resulted in cantons that were run by local dignitaries, but who were required to report to the French commanders and who had to follow their instructions. Their task consisted in the administration of justice, the mediation between the colonial power and the population, the collection of taxes and the procurement of forced laborers for public construction work. As a result, loyal men who were powerful in French came into the ranks of the previously dominant clans. The colonial regiment was structured centrally, with the highest representative of France being the lieutenant governor in Dakar . The commanders had the right to impose prison sentences and camp detention even for minor offenses. The trigger was mostly backward tax payments, refusal to perform forced labor, but also an alleged lack of respect for the colonial authorities.

French Sudan (from 1904)

In 1904, France annexed what is now Mali to the French Sudan colony . As early as 1893 France installed a civilian governor, but it was not until 1937 that the lieutenant governor of French Sudan became a governor , who now had to report to the governor general in Dakar. Mali was part of French West Africa until independence . Since 1899, the huge colonial area had been distributed more strongly to several of the neighboring colonies such as Senegal or Guinea, Dahomé or Ivory Coast ; a colony was created called Haut-Sénégal or Moyen-Niger (Middle Ages). As early as 1902 it became Senegambia et Niger . At that time, three military districts shared what is now Mali. On October 18, 1904, Afrique Occidentale Française was created as a combination of several West African colonies. Now the colony was again called Haut-Sénégal et Niger until 1920 , the three aforementioned military districts were incorporated into the colony. The capital in Kayes , which had existed since 1881, was relocated to Bamako in 1908, which had been accessible by rail since 1904. In 1911 the area of today's Niger was split off, and in 1919 that of today's Burkina Faso under the name Upper Volta (Haute Volta). French Sudan was restored on December 4, 1920, Upper Volta abolished in 1932, to be restored in 1947. The governor was not replaced by a high commissioner until 1959. From 1899 to 1908 William Ponty , from 1924 to 1931 Jean Henri Terrasson de Fougère's highest deputy in France, and from 1946 to 1952 Edmond Jean Louveau . Ponty, whose full name was Amédée William Merlaud-Ponty, was Governor General of French West Africa from 1908 to 1915.

As in other French colonies, the inhabitants were gradually forced to grow export-oriented products, primarily peanuts , cotton and gum arabic , initially through forced labor and later through the collection of taxes. As in the neighboring Upper Volta, the legacy of this policy, which focuses on export crops instead of food crops, is still an immense problem within the country's agriculture today to produce manufactured goods for the colonies that could have rivaled French goods. Accordingly, trade developed weakly and the caravans became smaller. Slavery only played a role for the oasis economy and the slave trade largely disappeared.

Even after submission, structures below the top level continued to exist, but France tended to gain access to every single one of its subjects. This established a modern, centralized administrative state. At the same time, traditional territories with their grazing rights, tribal relationships, Sufi brotherhoods and market communities were often cut up and combined into new units.

The constitution, which the French National Assembly adopted in October 1946 and which formed the basis for the Fourth Republic , gave the colonies greater say. The territorial assemblies could now elect delegates with advisory rights, as well as representatives known as senators. In addition, the residents were able to dispose of the resources of the respective colony much more. Above all, however, the category of sujet was abolished in all colonies, with which one had designated residents who had no civil rights and were subject to indigénat , the customary law. The inhabitants of the colonies became French citizens, a huge increase in the number of citizens, of whom there had been only 72,000 in all of West Africa in 1937.

Road to independence (from 1956)

The political doctrine of the French Republic was based on fundamental rights that every citizen now had in the colonies. Through education in schools and at the École normal William Ponty near Dakar, Africans were increasingly finding leadership positions, but initially worked exclusively as employees, teachers or technicians until around 1930. The educated elite thus created became involved in the sectors of social, cultural and sports policy. The resulting movement was given an organizational unit by the writer, school teacher and administrative clerk Mamby Sidibé in the Association des Lettrés (about: Association of the educated). Sidibé was removed from Bamako and had to live in Bandiagara, but those who remained became involved in newly formed associations in which the question of independence was soon debated. At the same time, close ties developed across ethnic and religious boundaries among the alumni of the university in Dakar. The French encouraged them to join a maison du peuple (House of the People) and move into a house of the same name; the Amis du Rassemblement Populaire du Soudan Français (ARP), a group of colonial officers who supported the Popular Front government in France, supported them, but the colonial government tried to control the independence movement through the ARP. In 1937, a teachers' union led by Mamadou Konaté was the first union in the country. This laid the foundations for a mass movement. Sissoko's supporters founded the Parti Progressiste Soudanais (PPS) in 1946 , which was supported by the colonial government because it aimed at greater participation, but in cooperation with France.

In August 1945 Africans were able to take part in national parliamentary elections for the first time. Among the candidates was the teacher and canton leader Fily Dabo Sissoko , who was an important representative of the traditional elite in western Mali. The colonial government saw in him a conservative representative and supported him. Modibo Keïta, on the other hand, was supported by the Groupes d'Études Communistes (GEC) and by the French Communists. But the first choice - mainly individual candidates - did not produce a clear result. This is why the first parties emerged, such as the short-lived Parti Démocratique Soudanais (PDS) in 1945 . After Sissoko's election, the Bloc Soudanais , founded by Modibo Keïta and Mamadou Konaté, was born. This was in turn supported as Union Soudanaise by the Communist Party of France until 1966.

According to the Loi Lamine Guèye of 1946, all citizens had the right to vote in elections to the French parliament and also in local elections. The right to stand as a candidate was not specifically mentioned in the law, but it was not excluded either. In the elections to the Paris Parliament, there was no two-tier suffrage in French West Africa as in other French colonies, but there was for all local elections. In 1956, under the French colonial administration, the loi-cadre Defferre was introduced, which guaranteed active and passive universal suffrage. This introduced women's suffrage .

In the 1956 elections, Modibo Keïta , who, like Mamadou Konaté, belonged to the Association des Lettrés , won a seat in the Malian Territorial Assembly and in the French National Assembly. Keita and his party, the US-RDA, then strove for independence, which brought them into strong opposition to the PPS. With the loi cadre of 1956, the rights of the governor general were already severely restricted. Sissoko changed the name of the PPS to PRS, Parti du Régroupement Soudanais , and later he and his supporters joined the US RDA. Konaté died of liver cancer in 1956, which paved the way for Keïta to power. On September 25, 1956, the French colonies decided in favor of autonomy in a referendum which gave them the choice between full integration in France, political autonomy within the French Community ( Communauté française ) or immediate independence. Only Guinea voted for independence. In October 1956 Keïta became head of government of the République Soudanaise.

On November 24, 1958, Sudan became an autonomous republic within the Communauté Française, but on March 25, 1959, only Mali and Senegal merged to form the Mali Federation .

Independent Republic of Mali (since 1960)

One-party regime (1960–1991)

After the French constitution of 1958 allowed the colonies full internal autonomy, the colonies of Senegal and French Sudan united on April 4, 1956 and declared themselves independent as the Mali Federation on June 20, 1960. The general right to vote and stand for election was confirmed. Keïta became prime minister. The demarcation between the states was arbitrarily determined by the colonial territory and did not adhere to traditions, peoples, grown relationships or hostilities. Accordingly, Senegal left the federation on August 20 of the same year, and the remaining part became formally independent as the Republic of Mali on September 22, 1960 . The army had previously been mobilized in the east and the police in the west. Keïta and his followers were removed from Senegal on August 22, 1960 in a sealed train and taken to Bamako. In contrast to many former colonies, the conflicts did not arise along ethnic lines, but along ideological lines. This is due to the fact that these conflicts were carried out between Bamako's ruling elites, i.e. they had a more urban character.

Modibo Keïta, the country's first president and secretary of the US RDA, put Mali on a socialist course. The French had to evacuate their military bases in the country, the administration was Africanized and in 1962 Mali left the franc association and introduced its own currency (however, the country returned to the association in 1967). State-owned companies were founded and industrialization was promoted.

However, about four years later, mismanagement and excessive bureaucracy forced the government to announce tough measures. This was accepted only reluctantly by the public because it did not hide the fact that profits were still being made. On May 5, 1967, the currency, which had not been convertible until then, had to be devalued by 50%. In 1967 a National Committee for the Defense of the Revolution (Comité National de Défence de la Révolution, CNDR) was established, which became active from August. It included Foreign Minister Ousmane Ba, Development Minister Seydou Badian Kouyaté and Defense Minister Madeira Keita, as well as the military Sékou Traoré . The President announced the takeover of power by the CNDR in a radio address. In January 1968, the National Assembly disbanded itself and authorized Keïta to appoint an assembly. The 3000-strong people's militia (Milice Populaire) was reactivated, and "purges" were carried out following the example of the Red Guards and the cultural revolution in China.

Moussa Traoré (1968–1991)

On November 19, 1968, Keïta was overthrown in a bloodless coup by a group of officers led by Colonel Moussa Traoré (see coup in Mali 1968 ). After the arrest of the president, the latter founded the Comité Militaire de la Liberation Nationale , initially consisting of 14 members, under the leadership of Moussa Traoré. US RDA and CNDR have been disbanded and banned. Until the end of the 1980s, the country was ruled by the leaders of this coup, who were initially unknown to the public and at the same time without any political or administrative experience. New laws were drafted that were valid until 1974. Moussa Traoré ousted the initially ruling Yoro Diakité from power, who had oriented itself more towards France and the West. Diakité died in prison in 1973 after being accused of plans for a coup in 1971, as did Malik Diallo . Mamadou Sissoko had previously died in a car accident in 1969 , so that now only eleven men ruled the country. In addition to Traoré, Filifing Sissoko , the theoretician of the regime, played a central role.

In view of the fact that most of the city's residents worked in the state economy and administration, the government had no choice but to hold on to it. Nevertheless, collectivized property was privatized again, the regular sessions on indoctrination ended and the associated organizational units dissolved. The taxes that had been used to finance the ruling party were also eliminated. In addition, the numerous paramilitary groups were dissolved and more personal freedoms were allowed. In addition to the economic problems, the government had to contend with a severe drought, as a result of which around 80,000 nomads migrated south.

On June 2, 1974, the government proposed a new constitution, which was approved by 99% of voters. A single party was now planned, plus a five-year election cycle for the president and a four-year election cycle for members of the National Assembly (shortened to three years in 1981). However, former members of the government and parliament were banned from any political activity for a period of ten years. But on September 22, 1975, Traoré announced the founding of a new party. The next year the Union Démocratique du Peuple Malien (UDPM) was created. In the course of 1975, 21 former comrades-in-arms had been released from prison; In February 1977 Keita returned to Bamako from Kidal in the northeast, but died unexpectedly on May 16. At his funeral there were demonstrations against the CMLN, which responded with mass arrests.

Democratization under Alpha Oumar Konaré (1992-2002)

On June 19, 1979, Traoré was democratically confirmed for the first time in the first elections to confirm his eleven-year presidency. The CMLN was formally dissolved on June 28, 1979. At the end of 1985 a dispute with the neighboring state of Burkina Faso escalated into war over the Agacher Strip , an area that only covered a few square kilometers. However, this conflict was settled after ten days and finally settled by a judgment of the International Court of Justice in The Hague, which was accepted by both states . In 1989, the external debt was $ 2.2 billion. In 1988, the Islamic city of Djenne and the historic townscape of Timbuktu have been UNESCO - World Heritage added list.

Unrest and demonstrations in Bamako and after a general strike on March 26, 1991 led to the overthrow of President Moussa Traoré by a "Council of National Reconciliation" led by General Amadou Toumani Touré , who became President of the Transitional State . On March 31, 1991, the Military Council transferred power to a civilian-dominated transitional committee that provided for free elections within nine months. The "Transitional Committee for Rescuing the People" consisted of 10 officers and 15 civilians, including representatives of the Malian human rights association, the trade unions and the student associations (see also Putsch in Mali 1991 ). On April 9, 1991, the former Finance Minister Soumana Sacko became Prime Minister of the transitional government. On July 14th, the interior minister responsible for internal security, Colonel Lamine Diabira, was arrested after a failed coup attempt.

Despite some concessions, internal pressure on the regime from the Alliance pour la Démocratie en Mali (ADEMA) and the Comité National d'Initiative Démocratique (CNID) had grown for a long time. In 1990 and 1991 there were violent clashes between police and demonstrators, on March 26, 1991 Traoré was overthrown in a military coup led by Amadou Toumani Touré , who was to become President of Mali from 2002 to 2012.

Under pressure from ADEMA and CNID, the Conseil de Reconciliation National (CRN) founded by Touré was dissolved and the Comité de Transition pour le Salut du Peuple was created. A new constitution was adopted on June 12, 1992, and elections were held on February 23 and March 8. The ADEMA received 48.4% of the vote, the CNID 5.5%, the US-RDA still got 17.6%. Alpha Oumar Konaré was able to unite 69% of the votes in the second ballot and was sworn in as President on June 8, 1992. His first five-year term was dominated by trials against Traoré and his followers, as well as the first Tuareg uprising. Added to this were economic problems and the ambivalent role of civil servants. In 1997 Konaré received 95.9% of the vote, but the constitution prohibited a third term.

In January 1992 a new constitution was passed, establishing the Third Republic . This was followed by the first democratic elections for the National Assembly in March and April. In June 1992, President Alpha Oumar Konaré , who emerged from direct elections, took office. On June 9, 1992, Younoussi Touré was appointed Prime Minister. Despite ongoing unrest, especially in the conflict with the Tuareg and an attempted coup at the end of 1993, Mali appeared to be a relatively stable republic after three successful ballots. After the end of Konaré's second and constitutionally last term of office, power passed peacefully to the former General Amadou Toumani Touré . He was re-elected on April 29, 2007 for a second and final term of office. Two free and democratic local elections were also held.

The country has been committed to strengthening African regional organizations since 1999. Ex-President Konaré was elected the first chairman of the African Union Commission in 2003 . In 2000 and 2001, Mali was the only black African member of the United Nations Security Council. Relations with the states of the European Union were shaped by the former colonial power France, but other countries had also intensified their relations with Mali in recent years. After the reference to the Eastern Bloc in the years 1960 to 1968, the USA now saw Mali as a stability factor in the region.

Catastrophic drought (1968–1985)

In the background, as is so often the case, there was a climatic change that led to considerable internal migration. As part of the Sahel zone , Mali was massively affected by the devastating consequences of the drought that lasted from 1968 to 1985 and "changed everything". The drought turned huge areas that were once used as pasture and arable land in desert, because the drought destroyed huge areas of the so-called bourgoutières , which served as pastures in the dry season until July / August and the rice farmers as protection against harmful fish, the fishermen in turn as Breeding area. At the same time, these areas were of high ecological value, because the plants, also known as hippopotamus, protected wild animals. The name of the plant goes on as Bourgou called Echinochloa stagnina back, a kind from the kind of chicken millet . This not only provided edible seeds, but also stabilized huge pastures as a buffer against the strongly fluctuating amounts of rain. Consequently, the disappearance of the bourgou meant the end of a centuries-old lifestyle for the desert nomads, at the end of which the trees were also destroyed to keep the cattle alive. The members of these nomadic tribes populate the Malian cities today as refugees. At the same time, the fish stocks collapsed. In 1982, under the leadership of the United Nations Sudano-Sahelian Office, a restoration program for the bourgoutières began on an area of 30,000 km².

Smaller Tuareg uprisings (1989–2008)

From 1989 to 1994 there were clashes with the Tuareg in the north of the country. 80,000 people had to flee their homes, 2000 died. The background was - in addition to the drought - the return of many migrant guest worker families from the oil industry in Algeria and Libya , which experienced a decline in these years. When the promised reintegration aid failed to materialize, protests broke out, which were answered with arrests and torture. The Tuareg took up arms, raided police stations and planned to found a resistance organization. The state military also fought back with brutal violence against uninvolved civilians. On August 15, 1990, Amnesty International called on the Malian government to immediately stop the murder of the Tuareg. In May 1991 numerous Tuareg shops in Timbuktu were vandalized, and leading Tuaregs in other cities were shot without trial. On January 6, 1991, the Malian government and the Tuareg, who were fighting for more autonomy, signed a peace agreement in Tamanrasset, Algeria . The agreement provided for the demilitarization of the conflict zones and greater decentralization of the administration. In addition, the government should make more state investments in the north of the country. Only after the peace was it possible for the victims of this policy to return and gradually also to be accepted into the administration and the army. However, they are still waiting for the guaranteed autonomy to this day.

In July 2006 the Tuareg group Alliance for Democracy and Freedom (ADC; French Alliance démocratique du 23 mai pour le changement ) under the leadership of Ibrahim Ag Bahanga and the government of Mali in Algeria signed a peace agreement. In May 2007, serious unrest broke out again in the Kidal region. In March 2008 the ceasefire was broken again and the Tuareg group around Ibrahim Ag Bahanga kidnapped numerous civilians and soldiers. After offensives by the Malian army, Ibrahim Ag Bahanga fled into exile in Libya .

In October 2009, the Malian government and the armed Tuareg groups from Niger and Mali signed a new peace agreement in which the government committed to better support the Kidal region , and the Tuareg said they would support the fight against al-Qaeda in the Maghreb to. In January 2010, the Tuareg leader Ibrahim Ag Bahanga returned to northern Mali from exile in Libya and intervened in the Libyan civil war on behalf of Muammar al-Gaddafi . Thereafter, the Tuareg groups returned to northern Mali with additional weapons at the end of 2011, and the fighting against the Malian army reached a new high in January 2012.

Amadou Tomani Touré (2002–2012)