History of Morocco

The history of Morocco in the sense of a history of the genus Homo ("man") goes back about a million years. The Homo erectus can be demonstrated for the period 700,000 years ago, the anatomically modern humans before 145,000 years at the latest. While in the Rif land development for the 6th millennium BC It could be proven that the producing economy advanced slowly against the appropriating ones of the hunters, gatherers and fishermen. The Berbers (Imazighen) possibly go back to the culture of the Capsien (from 8000 BC ).

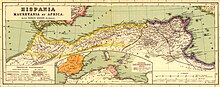

The Phoenicians coined from the early 1st millennium BC. The Berber cultures became increasingly popular, with Carthage asserting itself as the leading city in the eastern Maghreb . Cadiz maintained from the 7th century BC A trading post on Mogador . From the middle of the 5th century, Carthage expanded westward to the Atlantic , where bases were established. During the conflict between Carthage and Rome , the empires of the Massylers, the Masaesylers and the kingdom of Mauritania , which Rome annexed from AD 40 , emerged in the Maghreb . The southern border of the Roman province was secured by a chain of fortifications, the Limes Mauretaniae . Except for a few coastal cities, the province of Mauretania Tingitana was already lost at the end of the 3rd century.

The Christianization began in the 2nd century. Some Berber groups also adopted many aspects of Roman culture, including religions. In addition to the Christian religion , the Jewish religion also spread . In 429/435 vandals occupied the provinces of Numidia . As Arians , they fought the previously dominant church, while the Berbers were able to occupy large areas and develop their own tribal culture. In 533, Ostrom began to recapture the Vandal Empire, with the Berbers building up independent domains in changing coalitions. In the province of Tingitana, Ostrom could only gain a foothold in the far north.

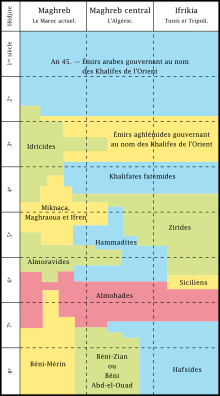

The Arab conquest of the Maghreb began in 664 . The Berbers initially resisted vehemently, but eventually found a home in an Islamic law school, which guaranteed them equality with the Arabs. On the other hand, these Kharijites demanded greater independence and so uprisings began around 740, which were initially suppressed by the armies of the Umayyads and the Abbasids . By 800 there were already three great empires in the Maghreb.

The overarching tribal groups of the Berbers were initially the sedentary Masmuda , then the Zanāta , who were later driven to Morocco, and the Ṣanhāǧa in the Middle Atlas and further south, but also in eastern Algeria . They formed an important pillar for the rise of the Fatimids . These were Shiites , but in 972 they moved their empire to Egypt . Now the Zirids and Hammadids made themselves independent. In return, the Fatimids sent the Banū Hilāl Arab Bedouins west. Arabic, previously spoken only by the urban elites and at court, now increasingly influenced the Berber languages. The Islamization was intensified, the Christianity disappeared.

The Almoravids restored the broken tribal alliance of the Ṣanhāǧa in the western Sahara and conquered the western Maghreb and with it Morocco, but also large parts of West Africa and the Iberian Peninsula (until 1147). They were replaced by the Almohads , who had their origins in a sect, conquered the entire Maghreb and also advanced to Andalusia . The up until then influential, viewed by the now predominant Sunnis as heretical but dominating among the Berbers, largely disappeared in the 12th and 13th centuries.

With the collapse of the Almohad Empire in 1235, the Moroccan Merinids temporarily conquered Algeria's north and Tunisia . Iberian powers, both Muslim and Christian, increasingly interfered. From 1465 to 1549, the Wattassid dynasty ( Banu Watassi ) ruled . With the fall of Granada and the unification of Spain (1492), one of the two great powers that dominated the western Mediterranean in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries came into play . The second great power was the Ottoman Empire , which initially opposed the Spanish with pirate fleets and tried to subjugate Morocco. The Spaniards conquered bases on the coast from Ceuta via Oran and Tunis to Djerba , the Portuguese mainly on the Atlantic coast.

In the fight against the Portuguese, the Saadians , who also relied on immigrants from Yemen , wrested power from the weakened Wattassids in 1549. In 1578 a violent advance by Portugal failed in the battle of the three kings at al-Qaṣr al-Kabīr . Under the Saadians, Morocco became an independent power, which - partly with Spanish help - was the only Arab state to successfully assert itself against the Ottomans. These could only occupy Fez for a short time. At times the militarily strengthened Morocco expanded under the Saadians to the Niger . On the religious level, the precedence of the Saadian caliphate to Chad was recognized by the king of Kanem and Bornu . However, the country split after 1603 after the death of the last Saadian ruler Ahmad Al-Mansur .

From 1492 onwards , Jews expelled from Spain came to Morocco as a result of the Alhambra Edict , which had a strong cultural influence on the north of the country. At times they exerted considerable influence on the economic and political external contacts of the Alaouites (Alawids) who ruled from 1664 onwards , who are still the kings and who trace their dynasty back to Ali , Muhammad's son-in-law . Morocco's rulers resided in different cities, which are now called the four royal cities . These are Fez , Marrakech , Meknes and Rabat .

However, the unitary state disintegrated again in the 18th century. The attempt to support the Algerian war for freedom against France further weakened Morocco. In 1912 the country became a French protectorate.

Spain also attacked Morocco several times since 1859 . The colonization of the north and the extreme south by Spain led to the use of poison gas in three wars in 1893 , 1909 and 1921 in the Rif . France also exerted influence, which culminated in the division of the country in 1912: a small part of the country in the north became a Spanish protectorate , a large part of the country French . France also encountered resistance that lasted until the late 1930s. The rule of the Governor General Marshal Hubert Lyautey and his ideas that European and indigenous populations should not mix, shape the image of many Moroccan cities to this day. With the Vichy regime , in addition to the racist colonial legislation, the anti-Jewish legislation of the National Socialists temporarily moved into the Maghreb. Its representatives and laws were tolerated by the US government for a while after the landing of Allied troops as part of Operation Torch in November 1942, until Resistance forces under Charles de Gaulle achieved a detachment in June 1943. At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, the Allies decided the "unconditional surrender" of the German Reich as a target of the Second World War .

In 1956 Morocco gained independence from France and Spain, and the majority of the approximately 250,000 Jews left the country. From 1975 Morocco occupied the Western Sahara . With the gradual democratization, parliamentary elections were decided for November 1997, which the left opposition won. A center-right coalition ruled from 2002 . An Islamist party won 107 of 395 seats in 2011, making it the strongest party.

Prehistory and early history

Old Paleolithic (from about one million years)

At the Casablanca sequence , the oldest finds in Morocco have been dated to around one million years. The oldest human remains come from the Grotte des Littorines and the Grottes des carrières Thomas 1 and Thomas 3. They have been dated between 400,000 and 600,000 years ago.

In addition to the sites near Casablanca, Tighenif in northwestern Algeria is the most important Acheuléen site in the African northwest. The lower jaw of Ternifine (today: Tighénif) was discovered east of Muaskar and initially referred to as Atlanthropus mauritanicus , today more as Homo erectus mauritanicus or Homo mauritanicus . It has been dated to be approximately 700,000 years old. This makes it the oldest human remains in Northwest Africa. In Salé , the neighboring city of Rabat, was found a skull has been dated to 450,000 years.

Finds from the Rhinoceros Cave and the Thomas Cave, both of which are located near Casablanca, have been dated to between about 735,000 and 435,000 years ago. The Sidi Al Kadir-Hélaoui sites were assigned to this phase, as well as Cap Chatelier, the Littorines and the Bear Caves. In this area around Casablanca, a large plain, the Acheuléen ends about 200,000 years ago. Cleavers , a special form of rectangular hand ax, are numerous as early as the 1,000,000 to 600,000 year phase, and the levallois technique came into use.

Hundreds of artifacts were found in the area of the mouth of the Oued Kert near the Mediterranean coast, west of Melilla . Most of them seem to belong to a very archaic facies of the Acheuleans. Ammorene I, located a little south of a spring, can be dated to the end of the Acheuléen, as demonstrated by the finely crafted hand axes with a thin cross-section. In the southwest, in the Tarfaya region, there were also indications of this technique.

Atérien: anatomically modern man (more than 145,000 years ago)

The carrier of the North African Atérien culture was anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ), who - in terms of their genes - are largely identical with today's humans. The culture may not have developed until the Maghreb. According to Moroccan finds, this happened 171,000 to 145,000 years ago.

This anatomically modern human appeared more than 200,000 years ago in East Africa and soon appeared in Morocco, as has been proven at several sites, including Témara on the Atlantic coast, Dar es Soltane 2 and El Harourader. The Atérien thus has a key position in the question of the spread of Homo sapiens in the Maghreb and (possibly) Europe. In any case, in the Maghreb the later hand ax complexes were followed by the teeing industries ; and blade tips that belong to the later Aterian tradition, were found. The people of Atérien were probably the first to use bows and arrows.

The Atérien, named after the site of Bi'r al-'Atir southeast of the Algerian Constantine , was long considered part of the Moustérien analogous to Western European development. However, it is now considered a specific archaeological culture of the Maghreb, which reached a very high level of processing of its stone tools. She developed a handle for tools, combining different materials to make composite tools . The main shape is the atérien tip equipped with a kind of mandrel, which is suitable for being fastened in a second tool part.

The oldest of this culture assigned archaeological site, Ifri n'Ammar, one in the Rif foothills on a connecting road to Moulouya located Abri , dates back 145,000 years. Mousteria artifacts there even go back 171,000 years. Other sites also reached an age of more than 100,000 years, so that settlement from the eastern Sahara is now considered unlikely. On the contrary, the eastern sites of the Atérien are considerably younger, as evidence sites in Libya show. However, caution is advised here too, because an Atérien blade was found in Egypt's Kharga oasis, which has been dated to over 120,000 years.

It is possible that the first anatomically modern humans did not come to the Maghreb with the Atérien culture, but developed it locally, perhaps in Morocco. The oldest human remains found there is around 300,000 years old ( Djebel Irhoud ). Moustérien artifacts were found there, but none of the Atérien. The typical shaft could have developed independently of one another in Europe and North Africa.

It is possible that a cultural loss can be established in the late Atérien, because so far there is no known evidence of (body) jewelry, such as was found in the Grotto des Pigeons in Taforalt in southeast Morocco. Thirteen pierced snail shells of the species Nassarius gibbosulus were discovered there, which were dated to an age of 82,000 years. The shells come from the Mediterranean, were transported 40 km, decorated with ocher and pierced so that they could be worn as a chain. They are considered the oldest symbolic object. Some archaeologists ascribe the emergence of a symbolic level to modern humans, as it were as a biologically determined genetic material , while others already see this pattern among the Neanderthals in Eurasia. In addition to biological approaches, cultural or climatic causes are also discussed.

Epipalaeolithic, Ibéromaurusia (17,000–8,000 BC): beginning to settle down

The period from around 25,000 to 6,000 BC In the Maghreb, BC includes both hunter-gatherer cultures as well as those of the beginning transition to the sedentary, then rural way of life. As in many regions of the Mediterranean, the transition to agriculture was preceded by a long phase of increasing locality. This long-term development was largely determined by climate changes.

The last maximum extent of the glaciation did not reach the North African coast, but colder northwest winds led to a drier climate. Pollen studies have shown the increase in steppe plants in the region. The Ifrah Lake in the Middle Atlas offers pollen finds from the period between 25,000 and 5,000 BP . They show that the temperature during the last glacial maximum (21,000 to 19,000 BP) was an average of 15 ° C lower and that precipitation was around 300 mm per year. From 13,000 BP, temperature and precipitation rose slowly, between 11,000 and 9,000 BP there was a further cooling.

The Ibéromaurus , a culture widespread on the North African coast and in the hinterland, can be traced back to between 15,000 and 10,000 BC. BC on the entire Maghreb coast. The most important site is the Moroccan Ifri n'Ammar. Their distinctive artifacts, microlithic back tips , were found between Morocco and the Cyrenaica , but not in parts of western Libya. It extended southward in Morocco to the Agadir (Cap Rhir) region. The back tips were made into composite devices, for example in pairs to make glued, double-edged arrowheads. The proportion of the tips of the back regularly makes up 40 to 80% of stone tools.

The oldest traces of painting in North Africa have been discovered in Ifri n'Ammar's Ibéromaurus. They were sealed by layers of culture between the 13th and 10th millennium.

In addition to the lithic industry, a highly developed bone technology emerged. The bones were made into small tips, but also decorated. In addition, mussel shells were processed, apparently not for jewelry, but rather as components of water containers. In Afalou there were formed from clay and fired at 500 to 800 ° C zoomorphic figures, but also scribbles were found, such as on impact stones (cobbles), such as the mane sheep of Taforalt. The mane sheep, which is a goat-like species , was an important source of food. At the Tamar Hat site, 94% of the ungulate bones were found, which led to considerations as to whether the animals could not have been herded. It is controversial whether this type of controlled keeping or hunting came into practice in times of greater drought, only to be given up again in favor of previously common forms of hunting when the humidity increased.

It is unclear whether the culture spread from east to west along the coast or on a more southerly route. The culture can be detected up to 11,000 BP, probably even up to 9500 BP. Genetic studies have shown a close relationship with populations from the Middle East.

The oldest burial sites come from the Algerian sites Afalou-bou-Rhummel and Columnata, as well as from the Moroccan Taforalt. Anatomically, the dead belonged to modern man, but were built robustly. They were classified as “ Mechta-Afalou ” by Marcellin Boule and Henri V. Valois in 1932 , and declared as a separate “breed” for around half a century. This is all the more unlikely as the sites referred to by the authors belonged to the Capsien on the one hand and to the Ibéromaurus on the other, and thus belonged to two very different cultures. In any case, the Guanches of the Canaries were assigned to this breed without further evidence . Such classifications still haunt popular scientific literature to this day . In 1955 the "Mechta-Afalou breed" was even differentiated into four sub-types by sorting on the basis of mere visual appearance. Around 1970 further "races" were defined in this way. Marie Claude Chamla differentiated between “Mechtoide” and “Mecht-Afalou” - the former being more delicate according to their definition. This type had been discovered in the Algerian Columnata. It was found in Medjez II in one and the same layer with the other type.

The removal of mostly healthy teeth is noticeable, especially the incisors. Since there are no other traces of violence in the facial area, this was probably due to cosmetic, ritual or social reasons, such as status reasons. Something similar is stated for the Italian Neolithic.

At around 13,000 BP, piles of rubbish were produced which were predominantly composed of the shells of molluscs . They appeared a little before the Capsien sites in Algeria and Tunisia, the escargotières . In Ifri n'Ammar, Moroccan, there seems to have been pre-forms of sedentarism, because the spatial division of the demolition into workshop, living and burial areas was preserved for a long period of time. The Ifri n'Ammar Ibéromaurus and two other sites, namely Ifri el-Baroud and Hassi Ouenzga Plein Air, date between 18,000 and 7500 BC. BC, a recently developed stratigraphy in the coastal area now seems to close the gap between late Ibéromaurus and early Neolithic, i.e. the period between the middle of the 7th and early 6th millennium BC. It is possible that the people of Capsia, eastern Algeria and southern Tunisia, belong to the ancestors of the Berbers.

Pre-Neolithic pottery was found in Morocco from around 6000 BC. Apparently the hunters, fishermen and gatherers adopted Neolithic innovations, but stuck to their previous lifestyle. In addition, there was a kind of long-distance trade or exchange, including by sea, technological innovations and the formation of food stocks.

Neolithic (before 5600 BC)

Early and Middle Neolithic

Excavations until 2012 showed that ancient Neolithic finds from the "Rif Oriental" project up to 5600 BC. Go back BC. The most recent data from the coastal stations are probably even older. The Ifri Ouzabor site shows an epipalaeolithic layer under the Early Neolithic. The finds of the upper layer are already here around 6500 BC. And are therefore hardly a thousand years younger than the previous end date of Ibéromaurusien in the hinterland of the coast (Ifri el-Baroud).

It is unclear whether there was continuity between the hunter-gatherer cultures and the Neolithic cultures, as the custom of removing incisors persisted. While it was now seldom found in the east of the Maghreb, it was present in 71% of individuals in the west and again affected men and women equally. This may speak for a continuity of the population.

The grain types barley and wheat ( Triticum monococcum and dicoccum , Triticum durum and Triticum aestivum ) can be found in the Ifri Oudadane cave. There were also legumes such as lentils ( Lens culinaris ) and peas ( Pisum sativum ). One lens could be dated to 7611 ± 37 cal BP, making it the oldest domesticated plant in all of North Africa.

The oldest rock carvings in the Maghreb were found at Aïn Séfra and Tiout, both in the extreme west of Algeria, in the province of Naâma. On the mountain slopes of Mont Ksour up to El Bayadh there were pictures of ostriches, elephants and people. Apparently, hunter cultures persisted, as did cultures based on seafood. In Mogador on the Atlantic coast, a large number of waste piles, which consist of fragments of shell, snail shells, charcoal and other remains found. Forms of alpine farming were probably common, because in the mountain zone there were often buildings made of dry stone, but only rarely in connection with burial mounds that also contained additions. In the coastal area, the consumption of birds that are no longer found in Morocco today is detectable, such as the giant alkali , which was found in a cave southwest of Rabat, 300 m from today's coastline and dates back to 5000 to 3800 BC. Was dated.

In the cemetery of Skhirat-de Rouazi, at the mouth of the Oued Cherrat on the southern edge of Rabat, 101 burials and 132 ceramic vessels were found 6 m below today's ground level, which predate the bell-cup culture . The graves were dug on average 80 cm deep and sometimes sprinkled with ocher. 70 dead had received grave goods, including polished axes, mostly made of dolerite . In many cases the accompanying vases have broken and the shards scattered over the bodies of the dead. There were also ivory rings, thousands of discs made from ostrich eggs, and arrowheads. It is unusual that even the smallest children were given grave goods, and that two thirds of the children were buried. This is taken as an indication of an unusually high infant mortality rate. El Kiffen in the province of Casablanca is the second cemetery of this type, there were 43 vessels.

The only stone circle in Morocco is located about 11 km southeast of Asilah in the area of the place T'nine Sidi Lyamani. It is known as the tumulus or stone circle of M'zora and is about 5000 years old. It consists of 167 megaliths up to 5.34 m high, which were set up in a circle around a tumulus. The underlying, slightly elliptical hill has a diameter of more than 54 m in north-south direction and 58 m in west-east direction. Perhaps around 400 it was converted into a burial mound, which has since been surrounded by the much older stones.

Bell beaker culture in the north (around 2500 BC)

With the bell-beaker phenomenon , which in no way means a uniform culture created by migration or the spread of an ethnic group, copper metallurgy spread across Europe and thus laid one of the foundations for the early Bronze Age that followed. The archaeological culture spread between 2700 and 2200 BC. BC over a large part of the European mainland, the British Isles and partly also over the Mediterranean islands. A west-east spread from Portugal / Morocco to the Carpathian Basin and a north-south spread from Denmark to Sicily can be determined.

Around Tangier there are artifacts of the late Neolithic bell beaker culture, shards were found near N'Ghar, but only half a century later at Nador Klalcha about 2 km north of Mehdia in the Kénitra region . In total there are perhaps twelve vases, which raises the question of the importation of these vessels. A few years ago, further bell beaker artifacts were found in Sidi Cherkaoui in Gharb.

“Libyans”, rock carvings, burial mounds, Libyan script

Perhaps since the Capsien , cultures of considerable continuity can be detected, which were later addressed as Libyans and which were long referred to as Berbers . However, this is not considered certain, which is why many authors prefer the traditional term "Libyan", which was used quite divergent by the Greeks. Due to the adoption of the Latin word for those who did not speak Latin, namely barbari , which was later transferred to the non-Arabic-speaking population, the region was often referred to as "Berberei". The "Berbers" call themselves Imazighen (singular: Amazigh). The derivation of today's Berbers from Capsia, however, implies an origin from Eastern Algeria and Tunisia, which is neither archaeologically nor linguistically undisputed. Linguistically, the influence of the Punic was assessed much more strongly; but this, too, is limited to little more than a dozen words that can be considered certain. The adopted words are limited to minerals ("copper", "nickel"), cultural objects such as "lamp", or cultivated plants.

Early archaeological traces that can safely be assigned to the Berbers are rare and mostly of small format (up to about 30 cm). In Morocco, rock carvings were found mainly in the middle valley of the Oued Draa . The Jarf Elkhil site, 22 km west of Oulad Slimane, dates from the Libyan-Berber era with at least 109 incisions. However, the largest site from this period is Foum Chena, 7 km west of Tinzouline. The westernmost Libyan sites of this kind were found around Tiznit in the southwest. Among the 257 depictions, 63 riders were found up to 2009, who, however, unlike many Saharan depictions, do not carry lances or other offensive weapons. The first depictions of Tiznit became known through the tour of Rabbi Mardochée Aby Serour in 1875.

There are hundreds of burial mounds around Foum Larjam, which must have been built by a largely sedentary population. They originated between the 1st millennium BC. And the implementation of Islam in the 8th century. They were built using black dry stone walls . They have a length of 4 to 12 m and a height of 2 to 4 m and are equipped with a hatch. The head of the dead is generally oriented to the southeast and towards Luke. The five paintings that were discovered at the site show human beings, a battle scene and geometric patterns.

From around 2500 BC The Sahara, which existed between about 9000 and 3000 BC, became Was relatively densely populated, again so dry that numerous groups were forced to seek out cheaper areas. Around 5000 BC The slow dehydration began. It initially affected the Regs and Hammadas , with the lakes of the former landscape type drying up and forming the ergs with the sand freed from the water (like the small Erg Chebbi near Sidschilmassa ), sometimes huge areas of sand that cover about a tenth of the Sahara. For a long time the high mountains, rising to over 3000 m, received plenty of water and released their water into the rivers. In the oases, on the other hand, the underground water reservoirs that were created over thousands of years of rain are still being tapped. The Sahara became a difficult but often visited region, which also acted as a bridge between the landscapes north and south of the desert that had now been transformed by the Neolithic. Written sources only set in the 2nd century BC. Wider a. At that time, the Berber culture had not only become strongly regionalized, but it was in constant exchange with the cultures of the Sahel and across the Mediterranean with southern Europe and the Middle East.

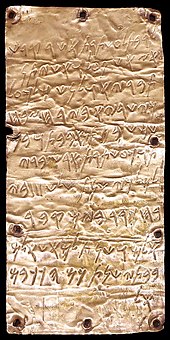

The Libyan script (also called Old Libyan or Numidian) is an alphabet script dating from around the 3rd century BC. Was used in much of North Africa until the 3rd century AD. Possibly it goes back to the Phoenician alphabet. The Tifinagh script emerged from the Libyan script . In Morocco, as in other Saharan countries, the use of writing was made a criminal offense until the 1990s. Today Tifinagh is taught in schools.

Phoenicians, Carthaginians

Around 800 BC Phoenicians, especially from Tire and Sidon , began to establish settlements in North Africa, such as Carthage. Cities such as Migdol, later called Mogador, now Essaouira , emerged in Morocco . They were looking for bases for their trade in Spanish silver and tin.

The Atlantic coast became from the 7th century BC. Visited regularly, especially by Phoenician traders on their way to Spain, who apparently had no contact with the actual Phenicia, but with Western Phenicia, especially Gadir ( Cádiz ). At the same time, the traders from Gades visited the Atlantic coast to the island of Mogador (Cerne), which served as a trading post for two centuries (but possibly also up to the Moorish-Roman period). Mogador belongs to the second wave of Phoenician expansion that started from centers in the west.

Recent excavations have shown that the Islas de Mogador (also Islas Purpurinas) located in the bay of Essaouira was used intensively by the Phoenicians to breed purple snails . With around 130 evidence, graffiti is more numerous in Mogador than in any other West Phoenician settlement. Among them is a dedication to Astarte .

Around 600 BC The trading metropolis Carthage dominated the development. A chain of bases reached as far as the Atlantic coast, some of them were founded by Carthage, perhaps also by Tingis ( Tangier ). In the 6th century, the city probably also dominated the Phoenician bases on the Atlantic. The hinterland was opened up, certainly with the consent of the regional Berber powers, from there via the Loukos and the Sebou . Carthage controlled Melilla , Emsa, Sidi Abdeslam del Bhar, Tangier, Kouass, Lixos , El-Djadida, Thamusida, Sala and Mogador . Inland, Tamuda ( Tetuan ), Banasa and Volubilis were added. In addition, the Carthaginians occupied Gibraltar and probably blocked the passage into the Atlantic in the course of the 4th century. Carthage also succeeded in 580 BC. To defend the Phoenician colonies in western Sicily against the Greek colonies on the island. This made the city the reference point for all colonies in the western Mediterranean. After Tire had also fallen into Persian hands, Carthage was the only Phoenician great power.

Trade routes led south to the areas beyond the Sahara, which, presumably through intermediaries, brought goods to the coast. Iron and copper were obtained from the Etruscans, and tin, gold and silver were offered. Presumably it happened before 540 BC. To corresponding contracts.

Carthage is believed to have around 400,000 inhabitants. Their chief god was Baal Hammon , during the 5th century BC. In BC the goddess Tanit became more and more respected. Melkart from Tire and Eschmun , who was identified with Asklepios , fell far from these two main gods .

Carthage closed in 508 BC. A first treaty with Rome, 348 and 279 others; there were no conflicts. However, when Messina died in 264 BC. Subordinate Rome to a war that lasted until 241 BC. Lasted. There were three wars in total . When it was 241 to 237 BC When there was a serious uprising, the so-called mercenary war, a Numid rebellion is said to have followed. The inscription Libyan appeared in Greek on the coins of the insurgents . Carthage began to conquer the south and east of the Iberian Peninsula after the first war against Rome and it expanded its influence on the Numidian coast.

Mauritania, Massyler and Masaesyler

Expansion of Carthage, tribes in what is now Morocco

Before the 2nd century BC Little is known about the Moorish tribes in the west. Ptolemy compiled a list of the tribes that inhabited the far west of Numidia in his day. This is what he calls the Salinsai around Sala and Volubilis , who appear as Salenses in the sources of the 2nd to 4th centuries. The Ouoloubilianoi lived in the Volubilis area. He also called Zegrenses and Banioubai which he situates but much further south than later sources indicate this. He names them and the Ouakouatai as the southern neighbors of the Nectibenen , who probably lived in the Marrakech plain . It is assumed that they lived in the area of the Banasa founded under Augustus . The localization of further tribes causes difficulties, whereby the Makanitai can probably be identified with those tribes to which the name of the city Meknes goes back.

Massinissa and Syphax (until 202 BC)

Again and again there were battles between the two eastern Numider empires. In the case of the Massylers in the east, the proportion of the permanent rural population was considerably higher than further to the west. Massinissa , whose father was the first king, allied herself in the fight against Syphax , the king of western Numidia, during the Second Punic War . He attacked Syphax together with a Punic army under Hasdrubal and forced the Roman allies to make peace with Carthage. 213 BC Chr. Syphax had changed the front and allied with the Romans, so that the Carthaginians had to quickly withdraw from Spain. Massinissa, in turn, changed in 206 BC. On the side of Rome. But he was driven out of Eastern Numidia by Syphax. Massinissa crossed from southern Spain to Numidia and King Baga of Mauritania asked him - he did not want to be drawn into the war between Rome and Carthage - 4000 men available to escort him through the kingdom of Syphax. Massinissa was defeated, however, and Syphax was now the master of both Numider realms.

Syphax allied itself in 204 BC. Finally with Carthage. When Scipio the Elder landed in Africa that year, Massinissa came to him as a nearly destitute refugee. Together with Laelius , Massinissa defeated Hasdrubal and Syphax. Hannibal, who had returned from Italy, was finally defeated by Zama and had to 193 BC. Flee from Carthage. For Numidia, in addition to Carthage's drastic power restriction, the most important contractual clause was that the city could no longer wage war without Roman consent.

Roman client kingdom Numidia (from 202 BC), Mauritania

Cirta became the capital of Numidia . First, Massinissa came across between 200 and 193 BC. BC to the west, while Baga remained neutral. Massinissa supported the Romans who ruled the city in 146 BC. Destroyed, reluctantly against Carthage.

His kingdom was divided between the king's sons Micipsa (until 118 BC), Gulussa and Mastanabal . Micipsa, who survived his two brothers, died in 118 BC. His nephew Jugurtha attacked the capital Cirta in the follow-up dispute in 112 and thus prevailed. The military operations that led to the Yugurthin War were conducted only half-heartedly. 111 BC BC Consul Lucius Calpurnius Bestia went to Numidia, but he concluded a peace that was advantageous for Jugurtha. Thereupon the tribune Gaius Memmius Jugurtha invited to Rome. He did travel there, but when Jugurtha had a possible rival murdered in Numidia from Rome, he had to flee. Gaius Marius was charged with suppressing the uprising. One of his sub-generals, named Sulla , negotiated the extradition of Jugurtha from his father-in-law Bocchus of Mauritania. Gauda , a half-brother of Jugurtha, and Bocchus of Mauritania inherited his empire .

Bocchus I, who lived until 108 BC. He had kept neutral afterwards Jugurtha, who had promised him a third of his empire, supported him, but 105 BC. He had handed it over to the Romans. They now recognized him as a "friend of the Roman people". After his death in 80 BC His sons Bocchus II and Bogudes followed him. After the death of the latter, the divided Mauritania, whose western part Bogudes had ruled, was reunited.

Roman client state (until 40/42)

After Caesar's victory over the Pompeians and thus over Juba I , the Massylian empire was divided up. Bocchu II of Mauritania, an ally of Caesar in the war against Juba, received Western Massylia and Eastern Massylia, i.e. the area around Sitifis .

The Kingdom of Mauritania was founded in 33 BC. Chr. Bequeathed to Rome in will by King Bocchus II. Augustus put Juba II in 25 BC. As ruler over this client state . In 23 AD his son Ptolemy followed him to the throne. He put down the Tacfarinas revolt against Rome . This uprising, led by a Moorish soldier trained in Roman service, lasted from 17 to 24. On the occasion of Ptolemy's visit to Rome, Emperor Caligula had him murdered in AD 40. He wanted to annex the leaderless empire. Resistance to the occupation under the freed Aedemon was soon put down.

After the region of 33 BC Came to the Romans, they founded colonies in Zilil, Babba (not localized) and Banasa , which arose as Iulia Valentia Banasa between Tingi and the Oued Sebou (Sububus flumen); the main centers in the south were Sala Colonia (Chellah on the outskirts of Rabat) and Volubilis .

Part of the Roman Empire (40/42 to about 285/429 AD)

Mauretania Tingitana Province, securing the southern border, Romanization

Suetonius Paulinus was the first governor of the new province to enforce Roman rule from 42. Emperor Claudius divided the territory of the kingdom into the provinces of Mauretania Caesariensis with the capital Caesarea (Cherchell) and Mauretania Tingitana with the capital Volubilis , in late antiquity ( Tingis ). The governor had 5 to 10,000 men at his disposal, who were distributed over at least 15 camps. A straight line of defense ran eastward from Sala, now known as Seguia Faraoun (Channel of the Pharaohs). On Sebou the camp Thamusida and Souk el-Arba were, after all, were to Volubilis garrisons in Sidi Moussa bou Fri, Aïn Schkour (north of Moulay Idris created) and Tocolosida (Bled Takourart).

With the Limes Mauretaniae an attempt was made to secure the southern border of Mauritania and Numidia in the long term. The Limes of the two Mauritanian provinces, however, was not conceivable as a continuous fortified border wall because of the enormous length of the border, which stretched from the Atlantic to the eastern border of the Caesariensis province. Instead, barriers (clausurae) were primarily built in the valleys of the Atlas, as well as trenches (fossata), ramparts, but also a number of watchtowers and forts. The facilities were connected by a road network designed according to strategic aspects. The Severians had a number of forts built in the western Caesariensis.

The Tingitana was additionally secured by forts in Thamusida, Banasa and Souk el Arba du Rharb along the Sububus (Sebou) leading into the interior of the country . The Roman troops concentrated on the forts on the coast and around the 42 hectare provincial metropolis of Volubilis, which was elevated to a municipium with the occupation . Inscriptions show that Jews, Syrians and Iberians lived here as well as the indigenous population. The main product of the region was olive oil . The protection of the city, which, as a Punic inscription shows, has been around since at least the 3rd century BC. In the second half of the 2nd century AD, a new city wall with eight gates as well as numerous camps and observation posts served in its vicinity. The Sala, located on the coast, was sealed off from the Atlantic to Bou-Regreg by an 11 km long ditch, which was reinforced with a wall, four small forts and around fifteen watchtowers . Additional forts were built in Tamuda ( Tétouan ), Souk el Arba du Rharb and Ksar el Kebir on the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts.

On the eastern edge of the province of Mauretania Tingitana there were mountainous regions that were dominated by Berbers. Only Septimius Severus made an attempt at the beginning of the 3rd century to occupy these areas as well. As an exception, the governors Haius Diadumenianus (202) and his successor Sallustius Macrinianus received command of both provinces of Mauritania at the same time. As a result of unknown battles, a victory monument was erected 90 km east of Volubilis near Bou Hellou.

Even at the time of its greatest expansion in the province of Mauretania Tingitana, the limits of the Roman exercise of power lay on the Oued Lau (Laud flumen) and extended from there on the Atlantic southward and to Sala and Volubilis. At the latest in 290 the entire southern part of the province up to the Oued Loukos (Lixus flumen) had to be given up, apart from Sala and the occasional use of Cerne.

Individual finds such as IAM 2, as well as archaeological finds, which are quite numerous due to comparatively intensive investigations, gave a more compact idea of the Roman era. The easternmost finds were made around Bou Hellou, works on the main streets were made. However, in the absence of larger finds, it is also evident here that the Tingitana was a border region in which the streets were primarily used to connect camps, small forts and watchtowers.

Part of the Berber upper class sought integration into the Roman system of rule. For example, Aurelius Iulianus, head (princeps gentium) of the Zegrenses in the southwestern Rif, along with his wife and four children, received Roman citizenship in 177 . Already in 168/69 a Julianus, a prominent member of the tribe, received citizenship in recognition of his loyalty. The two appropriations are known as Tabula Banasitana . In contrast to the Zegrenses, who were regarded as provincials, the neighboring baquates were treated like foederati , i.e. they were outside the immediate Roman sphere of influence. Apuleius of Madauros, a city in northeast Algeria, was a representative of these groups, which were largely integrated into Roman society - he described himself as "half-numider and half- Gaetulians ", which means that he half counted himself among the Gaetulers , those peoples who lived south of the Atlas and the province of Mauritania as well as the Sahara west of the Garamanten to the coast. Men like these, whose works are part of world literature, show that these Berbers did not "catch up with history" through Islamization, as was assumed until a few decades ago. This is even more evident in the early 2nd century BC. Terence , born in Libya in BC , was the most important poet of the ancient Latin tongue along with Plautus and at the same time one of the most famous comedy poets of Roman antiquity.

Rome concluded 277 and 280 contracts with the above-mentioned Baquates. According to an inscription, Clementius Valerius Marcellinus, the governor of the province of Mauretania Tingitana, signed a treaty on October 24, 277 with Julius Nuffuzius, son of Julius Matif, king of the Baquats. An inscription a good two and a half years younger shows that the two contracting parties continued to regard the agreements as valid. In the meantime, however, the old king had died and his son Julius Nuffuzius had become king himself. The title “rex” was given to the leader of the Baquats, who incidentally had Roman citizenship, only in this context.

The peace was apparently not lasting, because a few years later Volubilis, a relatively large city of perhaps 40,000 inhabitants, had to be abandoned. Even under Marc Aurel , it had received a 2.6 km long city wall with seven gates and forty towers. However, the city was not evacuated because Romanized residents lived here in the 7th century. At least between 599 and 655 there was a Christian community with municipal institutions. Around 800 many of the residents moved to Moulay ldris , which was founded after 791.

Attacks by the local tribes caused Diocletian to take back the border in the Tingitana on the Frigidae – Thamusida line. Volubilis was now abandoned at the latest, while Sala probably remained Roman until the early 4th century.

Roman religion, society and state of late antiquity

The Roman religion came to North Africa mainly in the form of the triad Jupiter , Juno and Minerva . Even Mars played an important role as a god of war, it came up since Augustus the emperor cult. In addition to the official religion, old gods persisted and only received the new names. The Roman gods, for their part, were modified in the new environment. Saturn and Baal, Caelestis and Tanit could thus merge.

By today's standards, the Roman state was extremely "slim", downright minimalist. With the exception of the army and the highest jurisdiction, he delegated all state tasks to the approximately 2,500 cities scattered across the entire empire. Police tasks, road maintenance, fortifications, but above all collecting taxes, were the responsibility of the city assemblies. In addition, there were only trade associations, the collegia and corpora . In each city, perhaps 30 to 100 men, curiales , decided how the burdens were distributed among the citizens, and what share they themselves received of the rights and funds. Money was not the basis of power and influence, but the urban influence with its rights and privileges was the basis for becoming wealthy.

The total number of curials in the western empire may have been 65,000; in the east, which was much more urbanized, their number may have been higher. Accordingly, this curial class was concentrated where most cities existed, that is, around Rome and in central Italy, in southern Spain, on Sicily, around Carthage. The urban network on the Mediterranean coast of Gaul was a little less dense, then the north and south of Italy, Dalmatia, large areas of Iberia, as well as Numidia's north, in an area of perhaps up to 100 km from the coast.

Not only did the vast majority of the population live in these areas, but also the early Christians. Almost all of the authors who played a role in the clashes between pagans and Christians came from curial families. A rural Christianity appears in the sources only in the 4th and 5th centuries. This fixation on the city and the curial class brought to light debates about poverty and wealth that did not affect 90% of the population, because they had no share in the power or wealth of the curial. The corresponding writings were accordingly aimed at their own, politically closed class.

North Africa was largely spared from civil wars and invasions for a long time, so that the unusual prosperity of the 2nd century continued well into the 4th century. While in the endangered areas including Rome the construction of theaters, baths and arenas had to be withdrawn in favor of city walls and other defensive systems, this was much less pronounced in North Africa and occurred much later. In the 3rd century the tax burden was extended to all provinces and with increasing consistency and severity the taxes were collected.

The crisis of the 4th and 5th centuries, which Westrom did not survive, was of a different nature. 80% of the population worked in agriculture and contributed perhaps 60% to the total product of the empire, as much as these figures may be approximations. The harvest time ranged from spring in the south to late summer in the north. In the Mediterranean region, olive oil and wine were added from late autumn . Except in Egypt, the harvest volumes fluctuated so strongly that one can speak of shock-like jumps. Accordingly, the gods were inclined to an emperor when the harvest was good. Maximinus Daia believed that the gods consented to his persecution of the Christians in Tire because the all-important weather was extremely favorable. In the south of Spain, Christians who wanted to vote their God in favor by means of rituals demanded that the Jews not be allowed into the fields, because they spoil the effect of the rituals.

After all taxes had been deducted, the farmers had perhaps a third of the harvest, and what was even more serious, they had practically no buffer against the rigors of the weather and the poor harvests. The landowners themselves, the domini , rarely collected their own taxes. They had their land managers on site, who, like the curials in the cities, were collectors who, however, also had to endure the local conflicts. They sealed off the domini from it until they hardly intervened, especially since they were inaccessible to the country people.

At the same time, the economic area of the empire offered the wealthy completely different opportunities. They were able to stock up extensively and thus wait for more favorable sales times, i.e. higher prices, as they occurred before the new harvest, and above all they could cover greater distances to supply cities and armies. The farmers, on the other hand, were dependent on the local markets with their extreme price fluctuations. The wealthy benefited from regional and temporal price fluctuations every year. The largest grain traders were the emperors themselves. With the gold solidus , the borderline between the economy of the wealthy and the rest of society, which was dependent on bronze and silver coins, became constantly visible. The isolation of the social strata was also very clearly noticeable here, even by Roman standards, and thus fraught with conflict. In addition, this wealth had to be displayed in order to make the affiliation credible. The richest Roman senators had more income than entire provinces. Around 405, the young heiress Melania the Younger had an income of 120,000 gold solidi per year, which corresponds to 1660 pounds of gold.

Below this small group, there was a group of local landowners in the provinces who owned villas . Since Constantine, the emperors paved the way for them to enter the Roman Senate . This gave them more power and thus, according to the Roman principle, much greater wealth. They formed a kind of mediating layer, the members of which were entitled vir clarissimus or femina clarissima , and who often came from established provincial families .

With that senatorial rank, perhaps 2,000 men returned to their provinces. But some families had missed this “post-Constantinian gold rush” and feared their decline. It was mainly decurions or curials who feared social decline, falling into the large group of those who were also not safe from torture and the whip. In contrast, the system of patronage , of advancement through the mediation of influential people, helped above all .

Municipium and Colonate

Classical Roman society was subject to major changes as early as the 2nd century, but even more so during the imperial crisis. In 212 all cities of the empire received at least the rank of municipium , which brought the aforementioned financial burdens with it. Every male resident between 14 and 60 years old had to pay an annual tax. The small group of Roman citizens was exempt from this, however, the upper classes (metropolites) paid a reduced tax.

Imperial laws, presumably on the initiative of the large landowners, created the prerequisites for transferring almost unlimited power of disposition and police power to local masters, whose growing economic units were thereby increasingly isolated from state influence. The rural population was initially forced to cultivate the land and taxes (tributum) to be paid. Until the 5th century, the people who worked the land were often tied to their land while their property belonged to their master, but after three decades in this legal status others could take their mobile property or their property into their own possession. Under Emperor Justinian I there was no longer any distinction between free and unfree colonies. Colons and unfree were now used identically to describe arable farmers who were tied to the clod and no longer owned free property.

Since Constantine the Great, gentlemen have been allowed to chain fugitive colonies that had disappeared less than thirty years ago. Since 365 it has been forbidden for the colonists to dispose of their actual possessions, probably primarily tools. Since 371 the gentlemen were allowed to collect the taxes from the colonies themselves. Finally, in 396, the farmers lost the right to sue their master.

Christian churches in late antiquity

The church organization in the Tingitana was hardly developed. For example, not a single bishop from the province took part in the Synod of Elvira , which took place between 295 and 314, due to the lack of dioceses. Nevertheless, Tingis has a martyr, namely Publius Aelius Marcellus , who, according to legend, was a centurion who was stationed in Tingis and who refused to take part in the birthday celebrations of Emperor Maximian (286-305).

In contrast to the church of the years between 370 and 430, which was characterized by outstanding men like Ambrose of Milan , the situation between 312 and 370 was different. Although the clergy formed a separate class, which, like all priests of the various religions, was exempt from public service and personal taxation, the emperors denied churchmen access to the upper classes of society. In addition, this generated resistance among the curials, who were not exempt from taxes, because the more members of a community were exempt from taxes, the higher the burden on the others, because the city's taxes were passed on to all curials. Therefore one was constantly looking for wealthy relatives of the plebs , who could be called upon for tasks and duties by way of advancement.

In addition, the congregation of these clerics of the fourth century was by no means composed, as has long been believed, of the poor and marginalized of society. Recent research, such as that of Jean-Michel Carrié, shows that the members of the communities were artisans and civil servants, artists and traders. You sometimes referred to yourself as "mediocres".

Therefore, operatio , giving alms to the poor, was not only an important task, but also the life force (vigor) of the church, as Bishop Cyprian of Carthage wrote, as was the financing of church buildings. The former was especially important in times of persecution, for prisoners and refugees. However, this was only true for Christians, so that considerable amounts of money accumulated in the church. Therefore, Cyprian was able to raise 100,000 sesterces to free some parishioners who had fallen into Berber hands . It was this and the provision of the poor that earned the church state privileges. A privilege of 329 explicitly states that the clergy should be there for the poor while the wealthy, to whom the clergy did not belong, should go about their business. Ammianus Marcellinus expected verecundas from the clergy , the knowledge of the right place in society. But leading members of society who became Christians were soon able to move up in one train, displacing long-time comrades-in-arms, instead of long periods of training and experience. Ambrose of Milan was thus able to become bishop directly.

Vandal Empire (429 to 535)

In the course of the Great Migration , 429 perhaps 50,000 (Prokop) or 80,000 ( Victor von Vita ) vandals and Alans under the leadership of their war king Geiseric from Iberia to Africa. This corresponded to a force of about 10,000 to 15,000 men. Some Berber tribes supported them, as did Donatists , who hoped for protection from persecution by the Roman state church. In 435 Rome concluded a treaty with the Vandals, in which they received the two provinces of Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis, as well as Numidia.

In 439, however, they conquered Carthage, breaking the treaty, and the fleet stationed there fell into their hands. With their help, the Vandals managed to conquer Sardinia , Corsica and the Balearic Islands, and in 455 they even plundered Rome. But the Tingitana could not control them permanently.

The Vandals hung the Arianism to, a faith that in the First Council of Nicaea to heresy had been declared. Property of the Catholic Church was confiscated in its sphere of influence. The colonies tied to the ground may only have changed the masters; the imperial goods were probably simply converted into royal goods and served the ruling dynasty.

Geiserich's son Hunerich fought harder against the Catholic Church. Although it was also Cirta part of the Vandal kingdom, but at the same time were other Roman territories to own small states which were attacking the Vandals Empire in shifting coalitions. Hunerich's successor Thrasamund continued church politics. In the process, the vandals lost their reputation, on the one hand because they did not support the Ostrogoths , on the other hand because they could not find any means against the Berbers, who were occupying Vandal territory piece by piece. This was not only true for the west, but also for the heartland around the capital.

King Hilderich distanced himself from Arianism. The Moors, led by a certain Antalas, defeated a vandal army in eastern Tunisia. Masties made themselves independent and ruled the hinterland. He fought the Arians and possibly had himself proclaimed emperor.

When a conspiracy overthrew the king and brought Gelimer to the throne, Ostrom regarded him as a usurper . In 533 16,000 men landed under the command of the general Belisarius , won the battle of Tricamarum and occupied the Vandal Empire.

Eastern Byzantium on the coastline (from 533), Berber empires in the hinterland

Military and civil administration, diocese, exarchate

Carthage became the seat of an Eastern Roman governor, a Praetorian prefect who was responsible for civil affairs and to whom six governors were subordinate. For the military sector, a Magister militum was appointed for imperial North Africa, to which four generals were subordinate. The bishop of Carthage received the dignity of a metropolitan from the emperor in 535. There were a total of seven provinces, namely Proconsularis (also Zeugitana ) and Byzacium in what is now Tunisia, Tripolitania (northern Libya), Numidia (especially eastern Algeria), Mauretania Caesariensis (northwestern Algeria ) and Mauretania Tingitana (northern Morocco) and Sardinia. There were also five Duces in Tripolitania (based in Leptis Magna ), Byzacium ( Capsa and Thelepte ), Numidia ( Constantina ), Mauritania ( Caesarea ) and the Dux of Sardinia.

In 590, the Carthage Exarchate was created to pool military and civilian powers . Around 600 Herakleios became the Elder Exarch. In 610 his son of the same name, Herakleios , overthrew the Eastern Roman usurper Phocas while he was traveling to Constantinople with the Carthaginian fleet. When the Persians conquered large parts of the Eastern Roman Empire from 603, like Egypt in 619, Emperor Herakleios had plans to move the capital to Carthage. This did not happen, because he was able to defeat the Persians from 627 onwards.

Rising of the Stotzas, support in Mauretania

When 536 parts of the garrison troops in Africa rebelled against the Eastern Roman general Solomon, they elected Stotza's soldiers as their leader. The insurgents besieged Carthage. When Belisarius landed back in Africa, Stotzas fled to Numidia after a defeat. General Germanus , a relative of the Emperor Justinian , was able to defeat Stotzas, although behind his army there were some ten thousand Moors under Jabdas and Ortaias. But some tribes made alliances to Germanus even before the battle. Stotzas fled with a few faithful to Altava in Mauretania, where he married the daughter of a prince and is said to have assumed the title of king in 541. In 546 he was killed by an arrow in a battle, even if his army was victorious.

Striving for autonomy, Berber empires, Antalas and Cusina

Numidia played an increasingly independent role. The Berber's striving for autonomy had already intensified during the time of the Vandals, when large parts of the province of Tingitana in the west had become independent, possibly further encouraged by the religious policy of the Vandals. At least some Berber groups adapted the Roman legitimation model and called themselves rex gentis Ucutamani (CIL. VIII. 8379).

In 2003, Yves Modéran presented a fundamental study of the history of the Berbers during this period. In the time of the vandal, there was again an increased tribalization of the Berbers. It was even belonging to a tribe that actually made the Berber what it was, while the Roman language, Christianity or title in no way diminished this membership.

When the Vandals had been defeated but still offered resistance, Berber envoys from Mauretania, Numidia and Byzacena appeared at Belisarius and offered to place them under imperial rule. But they demanded an investiture, probably an installation in their offices secured by Roman titles. The princes Antalas, Cusina and Iaudas, who played a central role in the rest of the story, are likely to have subordinated themselves accordingly. Antalas, born around 499, son of the prince of the Frexes named Gunefan, had already started fighting the vandals in 529. As a result of his victory over their army in 530, the coup that had given Constantinople the legitimacy to intervene had come about.

One of the leaders of the uprising of 534/35 in the Byzacena was Cusina, whose mother was a "Roman". He was thus considered an Afrer , as the Roman-Berber population was called. After the defeat against Ostrom and Antalas, Cusina fled to Prince Iaudas in Numidia, who, after Modéran, was the worst known of the three Berber princes, but probably the most influential. He had risen against Ostrom in the eastern Algerian town of Aurès in 535, but Solomon was able to defeat him in 539. Nevertheless, Iaudas did not surrender, but fled to Mauretania. In 542 to 543 the region suffered the great plague , so that there was no further fighting. With the Berbers living in Libya on the Syrte, the Lawata, Antalas defeated the Romans under Solomon.

Arab expansion, Islamization

Split between Sunnis and Shiites

In 644, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān, a member of the Umayyads, was elected caliph. But in 656 he was murdered in Medina . ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib , the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet, was elected to succeed him. But as a supporter of the murdered Uthman, Muawiya was also proclaimed caliph in Damascus in 660 . The first civil war broke out within the great empire founded by Mohammed . Although Muawiya was able to assert his rule after Ali's murder by the Kharijites in 661, he was not recognized as the rightful ruler by Ali's supporters. The result was a schism between Sunnis and Shiites .

Resistance of the (Jewish) Berbers, Islamization

Under Muawiya I, the Arabs resumed their expansion , which had come to a standstill due to the above-mentioned conflicts. Africa was recaptured after the Eastern Roman exarch, together with the Berber prince Kusaila ibn Lemzem , had been crushed by Uqba ibn Nafi near Biskra in 683 .

Uqba's successor Abu al-Muhajir Dinar was able to win over the "Berber king" Kusaila (or Berber Aksil) in Tilimsān in northwest Algeria for Islam, who dominated the Awrāba clans in the Aurès up to the area around the later Fez . When Uqba returned to office, however, he insisted on direct Arab rule and rode to the Atlantic as far as Agadir . On the way back he was attacked on Kusaila's orders and with Eastern Roman support and killed in a battle. Against Kusaila, Damascus dispatched Zuhayr ibn Qays al-Balawī, who defeated Kusaila (before 688). A second Arab army under Ḥassān ibn al-Nuʿmān encountered heavy resistance from the Jawāra in the Aurès from 693 onwards. After the death of Kusaila, they were led by Damja, who was briefly called al-Kahina , the priestess. Their Berbers defeated the Arabs in a battle in 698, but in 701 the Arabs finally triumphed.

The Barānis were strongly influenced by Roman culture and were often Christian; they divided into two groups, namely the Maṣmṣda of central and southern Morocco and the Ṣanhāğa. This nomadic group living in the desert, to which the settled Kutāma of eastern Algeria belonged, later produced the Almoravids . The Zanāta failed to establish a permanent empire and they were forced to move to Morocco. Numerous Jews also lived in the Maghreb, which contributed to the legend that the Confederation of Kāhina was Jewish. Christianity disappeared over the following generations. For the Berbers it was crucial that you recognized some by their burnoos and others by their short tunics. The former supported the Arab-Islamic invasion, the latter were often Christians and were therefore subject to a tax that all non-Muslims had to pay.

If one follows Ibn Chaldūn (70–72), several Berber tribes were of Jewish faith. He calls the Nefoussaa around today's Tripoli , the Ghiata, the Medîouna (in western Algeria), the Fendelaoua, Behloula and Fazaz in Morocco Jews, as well as the Djerawa, who were subordinate to Queen Kahina and who lived in the Aurès. Jews may have turned to them before the Eastern Roman Christianization policy. Jews also lived in Sidschilmasa and Tafilalt, and oral tradition also suggests that Jewish states existed in the Draa Valley before the Islamic invasion. Until the 20th century, Berber Jewish communities existed in Ouarzazate , Tiznit , Ufran ((Anti-Atlas)), Illigh (southeast of Agadir) and Demnate .

Dynastic and religious battles, Berber empires

Kharijites, uprising of the Maysara, establishment of empires in the Maghreb

After stubborn resistance, most of the Berbers converted to Islam, mainly by joining the armed forces of the Arabs. Culturally, however, they did not find any recognition, because the new masters faced them with the same contempt as the Greeks and Romans. They also adopted the Greek word barbaric for those who had not learned their language or who had not learned it enough in their eyes. Therefore the Imazighen are still called Berbers today . They were paid less in the army and their wives were sometimes enslaved, as with subjugated peoples. Only Umar II (717–720) forbade this practice and sent Muslim scholars to convert the Imazighen. In the Ribats Although religious schools have been set up, but there are numerous Berber joined the denomination of the Kharijites , which proclaimed the equality of all Muslims.

As early as 739/40, a first uprising of the Kharijites began near Tangier under the Berber Maysara. In 742 they controlled all of Algeria and threatened Kairuan . The Warfajūma Berbers ruled the south in league with moderate Kharijites. They succeeded in conquering northern Tunisia in 756. Another moderate Kharijite group, the Ibāḍiyyah from Tripolitania, even proclaimed an imam who saw himself on the same level as the caliph. They conquered Tunisia in 758. The Abbasids , who overthrew the Umayyads in 750, only succeeded in retaking Tripolitania, Tunisia and eastern Algeria in 761.

Maysara al-Matghari, on the other hand, had succeeded in uniting the Miknasa , the Bargawata and the Magrawa . They defeated an army transferred from Andalusia. Maysara even assumed the title of caliph, but was murdered. Nevertheless, the rebels defeated an army in 740 in the Battle of Sabu ("Battle of the Nobles"), where they also defeated another army, which is said to be 70,000 strong.

The western Maghreb gradually gained independence, with the Berbers being supported by the fugitive Umayyads who had established themselves on the Iberian Peninsula. As early as 749 the Bargawata Empire was formed on the Atlantic coast and in 757 Miknasa founded the Emirate of Sidschilmasa . At the latest with the establishment of the Rustamids (772) and Idrisids (789) kingdoms , Damascus finally lost control of the western Maghreb.

The eclectic barghawata (from 749)

The founder of the small Barghawata empire was Salih ibn Tarif (749-795), who had participated in the Maysara uprising and rose to become a prophet. He proclaimed a religion with elements of Orthodox, Shiite and Harijite Islam, mixed with pagan traditions.

Under his successors al-Yasa (795-842), Yunus (842-885) and Abu Ghufail (885-913), the tribal principality was consolidated. The mission among the neighboring tribes was also started. After initially good relations with the Caliphate of Cordoba , it broke towards the end of the 10th century. Two Umayyad campaigns, but also attacks by the Fatimids , were repulsed by the Bargawata. From the 11th century onwards, there was a violent guerrilla war with the Banu Ifran . Even if this weakened the Bargawata considerably, they were still able to repel the attacks of the Almoravids . Thus died with Ibn Yasin , the spiritual leader of the Almoravids in the fight against barghawata in 1059. It was not until 1149 that barghawata by were Almohads as a political and religious group destroyed.

Kharijite Banu Midrar (Miknasa) around Sidschilmassa, Rustamiden in Algeria

The oasis settlement Sidschilmassa was founded in the middle of the 8th century and formed the center of the Banu Midrar from the Miknasa tribe . It is the second founding of Islam in the Maghreb after Kairuan in Tunisia, which was founded in 670. However, like the empires of the Rustamids and the Idrisids, it is not the foundation of an orthodox Islamic group, but also goes back to Kharijites, who were considered the first heretics of Islam by the other Muslims. The Kharijites had separated themselves from the Umayyads in 657 because they did not accept the procedure of determining the successor to the founder of the religion Mohammed. For them, in principle, anyone could lead the Muslim community ( umma ). Sidschilmassa managed to control the gold trade, which crossed the Sahara every two years by means of caravans, until the middle of the 11th century and at the same time to defend itself against the attacks of its neighbors who considered themselves to be orthodox.

To do this, the city needed strong defenses and in fact the citadel took up a significant part of the urban area. It was founded by Semgou Ibn Ouassoul, who is considered the founder of the Banu Midrar tribe. Until the 11th century, Sidschilmasa was the starting point for the western route of the Trans-Saharan trade . Through trade with the empire of Ghana , the city gained a prosperity that was highlighted by Arab travelers such as al-Bakri or al-Muqaddasi . Above all, luxury goods from the Mediterranean region were exchanged for gold, ivory and slaves. Their contacts reached as far as the Levant. Jews from Cairo lived in Sidschilmassa by the beginning of the 11th century at the latest. According to oral tradition, Sidschilmassa was not walled, but the oasis was surrounded by a 4 m high wall with four gates, as archaeological excavations have shown. On the other hand, Arab scholars report a wall, and it is also archaeologically tangible. It may have been abandoned at a later date in favor of the oasis wall.

After the Abbasid victory in 761, Ibn Rustam fled to the Zanata in western Algeria. After a renewed uprising of the Kharijites under Abu Quna and Ibn Rustam failed before Kairuan in 772, the latter withdrew to central Algeria and founded the emirate of the Rustamids in Tahert. In particular through the alliance with the Miknasa of Sidschilmasa and the Iberian Umayyads of the Emirate of Cordoba , the empire was able to assert itself against the Idrisids in the west and the Aghlabids in the east.

Shiite Idrisids (789–974), implementation of orthodoxy by Sanhajah

The western Maghreb was now of decisive strategic importance for the Umayyads, because only a Maghreb that was independent of the Abbasids and later the Fatimids was a guarantee of security against an invasion threatening from there. Therefore, the Umayyads supported the state formation there, including that of the Idrisids of Fez .

The founder of the dynasty was the Sherif Idris ibn Abdallah (789–791), a great-grandson of the Imam Hasan ibn Ali ibn Abi Talib . As a Shiite he was persecuted by the Sunni Abbasids and fled to the outer Maghreb in 786. There he was accepted by the Zanata. He settled in Walila, the Roman Volubilis. With the founding of the empire by Idris I in 789, the second of the permanently independent Islamic states of the Maghreb was created after the Rustamids.

Idris II (791–828) had a new residential town built on the other side of the river in 806, opposite the Fez military camp that was laid out by his father. With the settlement of refugees from Kairuan and al-Andalus in 818, the city quickly developed into a center of learning and the starting point for Islamization. The empire was also expanded through campaigns in the High Atlas and against Tlemcen , so that the Idrisids rose to become the most important power in the region against the principalities of the Bargawata on the Atlantic coast, the Salihids in the north of the Rif and the Miknasa in eastern Morocco and western Algeria and the Magrawa of Sidschilmasa . Although intra-dynastic disputes led to a political decline, this did not detract from the religious effect.

After the Miknasa had taken action against the Salihids in the name of the likewise Shiite Fatimids in 917 and had conquered their capital, they attacked in 922 under the leadership of Maṣāla b. Ḥabūs also joined the Idrisids of Fès, whose ruling head Yahya IV. But on the one hand one of the Idrisids managed to regain Fez, on the other hand the Umayyads were able to pull one of the Berber groups on their side and greatly expand their fleet operating on the coast. In the end, even the Miknasa governor of Sidschilmassa sided with the Umayyads when they conquered Ceuta .

Abd ar-Rahman III. , who ruled al-Andalus from 912 to 961, rose to the position of Caliph of Córdoba and seized the opportunity to conquer Melilla in 927 and Ceuta in 931. He was now allied with Idrisiden, Miknasa and Magrawa; a kind of protectorate arose over the western Maghreb against the Shiite Fatimids. It was not until 985 that the Fatimids, who never entered into direct battles with the Umayyads but only waged proxy wars, gave up their plan to conquer Morocco. They concentrated their forces on Egypt. The century-long struggle between Sanhadscha and Zanata ultimately led to the expulsion of the Zanata to Morocco and the relocation of numerous clans to the Iberian Peninsula. At the same time, with the victory of the Sanhajah, Orthodoxy took over almost everywhere, even if this tribal group initially appeared as an advocate of the Shia.

This glacis to the east, which the Umayyads had built, was lost again, but an 'Amridian governor ruled Fez until around 1016. The Idrisids, who were hardly able to speak Arabic, were finally expelled from Morocco. With Ali ibn Hammud an-Nasir , a non-Umayyad and at the same time an Idrisid descendant came to the throne for the first time in 1014, who was followed by his brother after his assassination in 1016.

Sunni Salihids

The founder of the Salihid dynasty was possibly a South Arabian warrior named al-'Abd aṣ-Ṣāliḥ ibn Manṣūr al-Ḥimyarī, who converted the surrounding Berbers to Islam under the Umayyad caliph al-Walid (705-15). For this he received from the caliph al-Walid I after the conquest under Musa ibn Nusayr the area of the Gumara-Berbers ( Masmuda ) between Tetouan and Melilla transferred as a fief. This principality developed alongside the Idrisid empire into one of the most important in Morocco.

At the end of the 8th century, the Nakur (al-Mazimma in today's al-Hoceima ) , which has existed since about 750, was founded by Sa'īd ibn Idrīs b. Ṣāliḥ al-Ḥimyarī, grandson of the founder of the dynasty, built as a new residence. It developed through the trade with al-Andalus under his son 'Abd ar-Raḥmān ash-Shahīd to an important trading center. A ribat, in this case a rural mosque , was built on the model of Alexandria . This was in marked contrast to Ifriqiya and el-Andalus, where Ribats always had military functions. Morocco went its own way early on.

The Salihids maintained good contacts with Cordoba and strengthened their relations with the Banū Sulaymān of Tlemcen , who were considered the descendants of the Prophet. This means of legitimizing rule was recognized among the Berbers and Arabs, and Tlemcen and the Idrisids of Fez invoked such ancestry. 'Abd ar-Raḥmān ash-Shahīd, who suffered from legitimacy problems due to his lack of traceability to the Prophet, made four pilgrimages to Mecca to compensate, but nevertheless had to fend off several Berber uprisings. Eventually he died trying to support the Umayyads (before 917). The Salihids were one of the few dynasties in the western Maghreb under which the Sunnis were promoted and in whose small empire they also made up the majority of the population.

Nakur was sacked by Normans in 858 and occupied for eight years; Members of the court had to be ransomed for high ransom money. The conquerors, who had already destroyed Algeciras , also attacked the Balearic Islands and the coast of southern France. Only in 866 did they give up Nakur again, which was now strengthened by the Salihids.

But at the beginning of the 10th century these got caught up in the battle between the Umayyads and Fatimids. The Salihid emir Said was asked by the Fatimid caliph al-Mahdi to submit. Because he refused, Nakur was attacked by the Miknasa- Berber Masala ibn Habus, the Fatimid governor of Tahert , and conquered in 917. While Said perished, his three sons Idris, al-Mutasim and Salih were able to go to Málaga to the Umayyad Abd ar-Rahman III. flee. He helped them regain Nakur, whom Masala had entrusted to a governor named Dalul after six months and then left. After the Salihids had taken the occupation by surprise, Salih took control of the city and ruled it as a vassal of the Emir of Cordoba. As early as 921, however, Nakur was taken again by Masala and after that (928/29, 935) several Fatimid attacks took place.

Religious center Tahert, the role of the Ibādīya (until around 940)

Tahert in the Rustamid Empire developed into the religious and cultural center of the Kharijites in the Maghreb. Many of them went there from the Middle East, where they were persecuted. The realm of the rustamids participated increasingly in the caravan trade and grain exports to Andalusia. Politically, however, the Imamate was unstable due to its dependence on the allied Berber tribes and disputes over a suitable ruler. After Ibn Rustam's death in 788, the Nukkar , a main branch of the Ibdadites that has existed up to the present, split off .

Under Muhammad (828-836) the Idrisid kingdom was divided between the twelve sons of Idris II. This created several rival principalities, the most important in the Rif Mountains among the Ghumara Berbers.

Flight of the Kharijites (909), origin of the Ibadites, separation of the Nukkār

In 909 the Imamate of the Rustamids was conquered by the Shiite Fatimids. The surviving Kharijites withdrew to Sedrata near today's Ouargla (not to be confused with Sedrata in the north-east of the country) in the Sahara. As the burial place of the last imam of Tahert, Sedrata developed into an important trade and pilgrimage center for the Ibadites. The beginnings of the Ibadis are in Basra in southern Iraq, which was a center of the Kharijites from the 680s. Jabir ibn Zaid from Oman worked here from 679 . He was a student of ʿAbdallāh ibn ʿAbbās and issued legal opinions , in which he relied primarily on Ra'y , the independent legal system of the legal scholars. Jābir, who died in 712, is considered by the Ibādites to be one of their most important authorities to this day. They only granted the other Muslims the status of ahl al- qibla , people who pray in the right direction of prayer, but who do not belong to the actual community.

Abū ʿUbaida converted his community into a mission network and sent men to the provinces of the empire with the task of planting Ibaadite churches. Most of these advertisers were also active as dealers. With the money they generated, a fund was set up in Basra, with which the community gained financial independence. Like the other Kharijites, the Ibadis were of the opinion that the imamate was not limited to the tribe of the Prophet Mohammed, the Quraish , but was open to everyone whom the Muslims elected to lead their state. They preached the principle of friendship and solidarity with all who lived in the spirit of Islam and avoidance of those who did not keep the commandments. The latter was directed primarily against the Umayyads.

Around 748 the Ibādites established their own imamate in Tripolitania, and around 750 the Ibādites of Oman paid homage to al-Dschulandā ibn Masʿūd, a descendant of the former ruling family there, as the first “imam of emergence”. Although this Ibaadite imam of Oman was overthrown by an Abbasid military expedition in 752, i.e. by the successors of the Umayyads, a new empire with Ibaadite orientation emerged with the Rustamid imamate of Tāhart in 778.