History of Libya

The history of Libya in terms of human settlement can only be traced back over a period of a little more than 100,000 years, even if traces of up to 2 million years old exist in North West Africa.

Libya is the Greek word for the area west of Egypt inhabited by "Libyans". Later the name extended to the whole of North Africa between Egypt, Aithiopia and the Atlantic.

Prehistory and early history

Paleolithic

Based on fossil and tool finds, it is considered proven that some representatives of Homo erectus left Africa for the first time around 2 million years ago for the Levant , Black Sea region and Georgia, and possibly via northwest Africa to southern Spain. About 600,000 years ago there was probably a second wave of propagation. In Africa about 200,000 years ago the early or archaic anatomically modern man emerged from Homo erectus and from this the anatomically modern man emerged. In contrast to the coastal fringes and the oases, the Sahara was only habitable in phases if sufficient rainfall allowed sufficient flora and fauna.

The Sahara was often drier, but also wetter for a long time than it is today, so it expanded or shrank. Phases of the “green Sahara” with their maxima were mainly concentrated around 315,000, 215,000 and 115,000 years ago, maxima of extremely dry phases can be found 270,000, 150,000 and 45,000 years ago. Accordingly, apart from a few refugia, the Sahara was probably a place that was hardly habitable for people from 325,000 to 290,000 years ago and 280,000 to 225,000 years ago. If people lived in today's desert at that time, they must have withdrawn to the south, to the Red Sea or the Mediterranean. Under these conditions modern man could have emerged who was repeatedly isolated for a long enough time and was constantly exposed to new conditions.

For example, 125,000 years ago there was an adequate network of waterways to allow numerous animal species to spread northward, followed by human hunters. Huge lakes such as the mega-Fezzan lake (over 76,000 km²) contributed to this, and in wet phases over the last 380,000 years they extended far north several times. In contrast, the Sahara extended northward to the Jabal Gharbi 70,000 to 58,000 years ago . This was followed by a wetter phase, which in turn was followed by a drier one 20,000 years ago.

,

The earliest traces of human settlement in what is now Libya do not only go back to the Atérien , when the more humid Sahara was crossed by hunters and gatherers . Remains from the Paleolithic were found in Tadrart Acacus in southwest Libya, in Jabal Uweinat in the southeast, but also 25 km northwest of it, in Jabal Gharbi 60 km south of the Mediterranean coast, as well as on the centrally located Shati Lake (100 to 110,000 years ago). Of the total of 56 sites (as of 2012), 25 are on the Jabal Gharbi (south of Tripoli) and 19 in the central Sahara on the Tadrart Acacus and in the Messak Settafet .

For a later wet phase, it is now assumed that Nilo-Saharan groups migrated from the east to the southern Sahara to stalk aquatic animals, while the northern Sahara was more likely to be visited by hunters of the steppe animals. So fishermen moved westward along rivers and lakes, some as far as northwest Africa, to hunt fish, crocodiles and hippos with their harpoons, while other hunters moved south to kill savannah dwellers such as elephants and giraffes with bows and arrows. The latter are probably assigned to the Epipalaeolithic and came around 8000 BC. From northwest Africa. Towards the end of the last Ice Age, Lake Shati became part of the much larger Lake Megafezzan , which, as recent studies show, were actually two lakes that were located 100,000 years ago over an area of 1350 and 1730 km², respectively stretched.

from Algeria

In North Africa, the late hand ax complexes were followed by the teeing technique , which is very similar to the southern European and Near Eastern. There are also leaf tips that belong to the later Atérien tradition. It is considered the culture of nomadic desert hunters and ended about 32,000 years ago. The Atérien was long considered part of the Moustérien, but now as a specific archaeological culture of the Maghreb. She had reached a very high level of processing of her stone tools. The hunters developed a handle for tools, thus combining different materials into composite tools for the first time. In Libya, 56 Atérien sites are known (as of 2012), 25 of which were found in Jabal Gharbi in the north-west of the country. The hunters and gatherers preferred higher regions further south as they came closer to their demands on the ecological environment. 70,000 to 58,000 years ago the Sahara extended northward into the area of the Jabal Gharbi, the next dry phase only followed around 20,000 years ago. The finds, whose reliable dating is still pending, must therefore be classified in time between these dry phases.

Usually, temporal parallels with Egyptian cultures can only be deduced typologically. The blades of Nazlet Khater are similar to those of Haua Fteah in Libyan Kyrenaica .

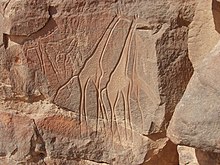

Some sites are known from the late Paleolithic in Libya. They go back between 21,000 and 12,000 years. The climate remained extremely dry, but many animal species withstood the increasingly extreme climate for a long time. North African ostriches ( Struthio camelus camelus ), which lived in the northern Sahara, were still known to the Greeks. However, the warming after the end of the last glacial period resulted in further massive changes. The floods were extraordinarily productive and reached areas that had hardly seen any water for a long time. The rock paintings and engravings come from the younger inhabitants, dating from 9000 BC. Insert.

At the western Egyptian site Nabta settled around 6700 BC. Shepherds with their cattle on a shallow lake barely 100 km from Wadi Kubbaniya, on the eastern edge of the Sahara. There were 12 round and oval huts there. Artifacts from the time between 7000 and 6700 BC were found near Elkab. The Elkabian industry was microlithic, millstones existed, but red pigments were found on many of them, so that they cannot be taken as evidence of agriculture. The inhabitants were more likely nomads who moved to the desert in the rainier summer and hunted and fished in the Nile valley in winter.

Neolithic

The living conditions remained extremely fragile and slight reductions in the already low rainfall drove the people away. In the western desert of Egypt a distinction is made between an early (8800–6800 BC), a middle (6500–6100 BC) and a late Neolithic (5100–4700 BC). The times between these phases were caused by the aforementioned return of the drought, which made the area uninhabitable. Ceramics were rare, and ostrich eggs were preferred for water transport . Pottery, the decoration of which refers to the symbolic level, is probably an independent invention of Africa. The tools of the western desert are closely related to the Fayyum culture, which existed between 5450 and 4400 BC. Existed. For the first time, agriculture became the basis of life there, which finally set the ways of life apart, albeit less drastically than long assumed. For example, domesticated forms of barley and durum wheat were found at the coastal site of Hagfet al-Gama (8900-4500 BP), which indicates a mixed culture of livestock, small-scale cultivation of some types of grain and collecting, because the finds were made together with remains of sheep and goats and land snails. After 4900 BC The amount of rain decreased again, even more after 4400 BC. Chr.

With the increasing dehydration since 3000 BC The Sahara developed into the desert we know today , in the last centuries before the turn of the times the last representations of animal species that have disappeared today were made, the nomads brought more and more goats and fewer and fewer cattle with them. Long-range migrations ensued, bringing into the desert groups that the neighboring Egyptians referred to as "Libyans", about whom the earliest news comes from the east.

"Libyans" and Egyptians

At least since about 4000 BC. Cultures can be identified that today are addressed as Libyans or their ancestors and that have long been referred to as Berbers . However, this is not considered certain, which is why many authors prefer the old term "Libyan". The "Berbers" call themselves Imazighen (singular: Amazigh). It was the Greeks who first extended the term “Libyan” to all inhabitants of the Sahara.

The first historical reports about “Lebu” or “Rebu” come from Egypt , which has existed since the 3rd millennium BC. Repeatedly reported of fighting with Libyans. Since around 2300 BC BC Libyans invaded the Nile valley and settled in the oases. Many of them were later accepted into the Egyptian army and eventually even become pharaohs themselves. The Libyans were only Egyptized to a certain extent. There are signs that religious forms have been adopted. In addition, the horse, which came from the Middle East, was now used as a riding horse and to pull chariots, came to Libya via Egypt. Around 1000 BC One of the Libyan tribes, the Garamanten , succeeded in establishing an empire around the Fessan. Perhaps they brought the horse and ironwork with them.

We get the earliest information from Egyptian inscriptions from the Old Kingdom (approx. 2686–2160 BC). A campaign by the pharaoh Sneferu , who was the first pharaoh of the 4th dynasty, was directed against Libya and took place towards the end of his reign. 1,100 Libyans and 13,100 head of cattle were captured during this campaign. His successor Cheops had an expedition carried out to the Dachla oasis in the Libyan desert, which served to procure pigment . Inscriptions testify that his son Radjedef also sent an expedition to Dachla. The inscribed evidence for this comes from a camp site in the desert, about 60 km from Dachla. This lies at the foot of a sandstone rock and was apparently referred to as the “Radjedef water mountain”. Reliefs in the mortuary temple of the Sahure pyramid (5th dynasty) tell of a campaign against Libya . However, since an almost identical image was also found in the pyramid complex of Pepi II , it is unclear whether an event is really represented or rather a symbolic beating of the enemies of Egypt, which had to be repeated by every new king. There were not only routes between Egypt and Libya along the coast, but also through the Libyan desert. So from Kharga a route went west to Dachla, where at the time of Pepis II there was an important station near Ayn Asil. Finds from the extreme south-east of today's Libya at the triangle of Egypt / Libya / Sudan show that the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom also made their claim to power in the south of Libya. There, in the area of the over 1900 m high Jabal al-Awaynat , a cartridge of the Pharaoh Mentuhotep II was found.

In the Middle Kingdom we hear of further expeditions against Libya. Amenemhet I had walls built on the eastern edge of the delta to protect against Asian invasions. In the last year of Amenemhet I's reign, his son Senusret ( Sesostris I ) moved against the Libyans.

In the New Kingdom , the pharaohs resumed their aggressive foreign policy. Seti I led a campaign to Libya. He also deployed the army against the Libyans, who were advancing into the Nile Delta from the west, probably out of hunger. Ramses II made Avaris, which had long been the capital of the Hyksos coming from West Asia, into his great capital, which was named Piramesse, 'House of Ramses'. This gave Ramses the means to secure the western border against the Libyans through a chain of fortresses.

In his 5th year of reign, Pharaoh Merenptah was faced with an invasion by a coalition against Libyans and previously unknown peoples. The leader of the invaders was the Libyan king Mereye, who, in addition to Libyan Mešweš , Tjehenu and Tjemehu, also led "peoples from the north", namely Šardana , Turiša , Luka , Šekeleša and Ekweš or Akawaša, who are counted among the so-called sea peoples , who are the political and the ethnic situation in the entire Eastern Mediterranean. Their traces can be found in the Aegean, they destroyed the Hittite empire, attacked the Levantine empires. Between the Cyrenaica and Mersa Matruh they went ashore for the first time within the Egyptian sphere of influence in the west and allied themselves there with the Libyans, so that an army of 16,000 men was formed. Since they had brought their women and children, but also their property and cattle, they probably planned to settle in Egypt. Merenptah saw himself on behalf of Amun, who had given him the sword, with which he waged a kind of "holy war". Though thousands were killed in the battle that Pharaoh won, many were captured and resettled in the delta. Your offspring should become an important political factor.

Ramses III. (1184–1153 BC) was also confronted in his second and fifth year in office with incursions by the Libyans as far as the central Nile Delta, who had allied themselves with the Mešweš and Seped. They too were defeated, but a few years after defeating the Sea Peoples, Libyans attacked the Nile Delta again. Ramses III. She did strike back, but a serious crisis intensified under Ramses IX. by incursions from Libyans to Thebes.

Rule of the Libyans in Egypt (approx. 1075–727 BC)

Eventually, the Libyans managed to rule Egypt for more than three centuries. The 21st dynasty from Smendes I is considered the Libyan dynasty. Even if the 22nd dynasty is referred to as the "Libyan" in the older literature, both the lower Egyptian royal house and the high priests and military leaders in Thebes must have been (at least partially) of Libyan descent as early as the 21st dynasty.

In contrast to the Cushites , the Libyan rulers did not adapt to the Egyptian culture, which is why they are referred to as "foreign rulers" in Egyptology. Their ethnic basis was the Mešweš or Ma as well as the Libu, which probably had their focus in the Cyrenaica. As shepherds, they had already threatened the New Kingdom, but there are also indications of permanent settlements in their homeland. Their leaders wore a feather in their hair; long lines of ancestors, which can be interpreted as symbols of illiterate peoples, were of great importance to them. The contrast to the rural, literate, rural Egyptians could not be greater. Egyptian centralism also did not fit in with their family-oriented form of rule, which was stabilized by marriage alliances, in which one of them was recognized as the overlord, but was faced with a number of more or less independent local princes. The Mešweš, which probably infiltrated earlier, held the better land around Mendes , Bubastis and Tanis , the Libu areas around Imau, which came later, on the western edge of their core settlement area in the western Nile delta. The Mahasun, who were also Libyan, lived south of them. The opposition of the Egyptians in Thebes to the Libyans was so strong that they continued to date after them even after the expulsion of the Kushite monarchs. They held out until the time of Psammetich I (664-610).

The Libyans found the lordly recourse to ancient Egyptian traditions at least useful, but these traditions changed under their influence. So their idea that several kings could exist at the same time contradicted these traditions. In addition, non-royal persons now carried out actions that were previously reserved for the Pharaoh alone. A Libyan chief turns his gifts directly to a god. Even temple donations, until then only made by the Pharaoh, could now be handed over by any wealthy person. The pharaoh was now a kind of feudal overlord, in whose tomb complex even people who did not belong to the dynasty could receive a burial chamber, such as a general named Wendjebauendjed in the tomb complex Psusennes I.

The accession of Smendes I to the throne around 1069 BC BC can be seen as the beginning of the 21st dynasty. It is possible that he obtained his legitimacy by marrying one of the daughters of Ramses XI. attained. He moved his residence to Tanis. But the king resided (also) in Memphis.

In essence, a theocracy had now emerged, Amun himself gave instructions to the pharaohs via oracles. Under Smendes, who ruled in Tanis, Upper Egypt was politically and economically almost independent and was administered by the high priests of Amun. However, the pharaoh was recognized as the ruler, as evidenced by the inscription on a stele in the quarries of Dibabieh.

Pinudjem I became high priest of Amun in Thebes around the time of Semendes' accession to the throne and was perhaps his nephew. The relations between Tanis and Thebes remained friendly and they were probably closely related. These relationships were further strengthened through marriages. The most famous king of this dynasty is Psusennes I (1039–991 BC), whose gold mask is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The 22nd dynasty founded by Scheschonq I (945–924 BC) is often referred to as the Bubastid dynasty . Manetho gives the royal lineage with the city of Bubastis in the eastern Nile Delta. Its founder was a Libyan. Although the Libyans had been defeated again and again by the pharaohs, more and more of them ended up in the Nile Delta. They may even make up the majority of the army. He himself was a nephew of the Tanite Osorkon the Elder; He married his son Osorkon (I.) to Maatkara, a daughter of the last pharaoh of the 21st dynasty Psusennes II. Through clever family policy, he managed to unite the empire under his power. He put family members such as his sons and his brother in high offices, etc. a. to the priesthood in Thebes. He conquered in a campaign around 925 BC. Parts of the Kingdom of Judah that paid him tribute, but that ended his offensive. After all, traditional trade contacts with Byblos were resumed. In the first four years, however, Sheshonq was only recognized as a pharaoh in Lower Egypt. In Upper Egypt he still carried the title "Prince of Mešweš " before he was mentioned as Pharaoh in Thebes for the fifth year.

853 BC The Assyrians threatened under Shalmaneser III. the northeast, so that King Osorkon II felt compelled to enter into a brotherhood in arms with Byblos in order to repel the Assyrian army. This was achieved by the allies in the battle of Qarqar on the Orontes . Under Takelot II it came in 839 BC. To a revolt of the Theban priesthood, which was suppressed by him. But a few years later the uprising flared up again, and it lasted around ten years. After his death, the sons fought for the throne. The younger declared himself king. Scheschonq III. (825–773 BC) ruled for more than half a century. His older brother Osorkon IV was mentioned 20 years later as the high priest of Thebes.

Egypt now split up into several small states. The 24th Tefnachtes dynasty (727–720 BC) ruled simultaneously with the 22nd and 23rd dynasties in the Nile Delta. He ruled the western delta and Memphis. He succeeded in making an alliance with the other dynasties against the Nubians advancing in the south. However, he lost around 727 BC. At Herakleopolis of the armed forces of the Nubians under Pianchi . This ended Libyan rule on the Nile.

Phoenicians and Greeks

The homeland of the Mešweš and the other Libyan tribes took a completely different development, because settlers from Greece arrived in Cyrenaica and from Phenicia in Tripolitania.

Since the 7th century BC BC began the Greek colonization on the Libyan coast . The newcomers settled in the Cyrenaika (Cyrenaika), the eastern part of today's Libya, and founded u. a. Cyrene (631 BC), Taucheira , Ptolemais , Barke , Apollonia and Euhesperides ( Benghazi ). The later Berenike was originally founded in this phase as Euhesperides.

Already at the end of the 2nd millennium BC Chr. Were Phoenicians from Tire and Sidon in what is now Tunisia, middle of the 1st millennium dominated there Carthage , which according to tradition 814 v. Was founded. With the emergence of the Hellenistic states in the succession of Alexander the Great , Carthaginian trade expanded eastward, and the merchants there were located in every major Greek city. The Phoenicians probably brought with them the cultivation of olives , which still thrive in Tripolitania today, but also brought figs and wine . The Libyans there often adapted the Phoenician culture and language, and many of the nomads became farmers.

Long before that, the Phoenicians had founded three important cities. These were Sabrata (7th century, a permanent settlement may not have existed until the 5th century BC), which was also founded by the Phoenicians from Tire; then Ui'at, which later became Oea (now Tripoli) and finally Lpcy, which the Romans called Leptis Magna . It is unclear whether Sirte, about 300 km further east, was also a Phoenician foundation. Carthage judged in Sabrata in the 5th century BC. A trading base, the same was true for Lpcy. Trade routes led south to the areas beyond the Sahara , which probably brought goods to the coast through intermediaries. The Garamantenstrasse, the later Bornuweg, led from Oea and Lpcy via the Fessan oases to the Kaouar oasis chain to Lake Chad . A caravan route led from Oea to Ghadames , from where roads led to Sudan . Control of trade in the western and central Mediterranean was much more intense. Carthage banned all non-Carthaginian ships from entering the North African coast and heavily taxed the Tripolitan cities. They provided their own soldiers or mercenaries, whose costs they had to bear themselves.

With the Persian conquest of the mother cities, relations there became more complicated and they broke with the destruction of Tire by Alexander the Great in 332 BC. Chr. Finally from. After Carthage's defeat in the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), the country came in 161 BC. Under the rule of Numidia . 46 BC BC Tripolitania came to Rome.

Developments in Cyrene, which was much more under Egyptian influence, took a completely different course. Pharaoh Apries (589-570 BC) led border battles against the Greek Cyrene, which led to his overthrow, because after a heavy defeat against the Greek colony, local soldiers rebelled, who should be put down by the general Amasis . After the return of Pharaoh Apries to the Nile Delta, the revolt escalated into an uprising against Greek supremacy. The uprising was now directed by Amasis himself and ended with Apries' fall and his escape. The victorious general ascended the throne. Amasis made an alliance with Cyrene that his predecessor had fought. In addition, he married a Cyrenian princess.

Persians (from 525 BC)

This alliance was still intact when 525 BC. The Persians attacked Egypt. Half a year after Psammetich III ascended the throne . there was a battle of Pelusion against the Persian attackers . Psammetich's army was defeated. After conquering Lower Egypt, Cambyses and his army moved further west. King Arkesilaos III. of Cyrene had to recognize the Persian suzerainty. He had been unwilling to accept the restriction of royal power imposed by Demonax under his father. After an attempted coup in around 530 he went to Samos , where he gathered an army with the tyrant Polycrates . With his help he broke the power of the large landowners in Cyrene and had the land redistributed. Most of his opponents fled to Barke.

In 525 Arkesilaos sent tribute to the Persian king Cambyses II. Arkesilaos, however , found a violent death in Barke, the stronghold of the oligarchs . With the help of the Persian satrap Aryandes , his mother Pheretime took revenge on the barbeques, as Herodotus reports. Under Darius I there were also unrest in Egypt, which the satrap Aryandes also put down until 519/18.

The new King Battos IV. , Who lived until 465 BC. Ruled, it was possible to break away from Persian supremacy. His son and successor Arkesilaos IV tried to strengthen his position by enlarging the Euhesperides on the Great Syrte , which had existed since the end of the 6th century , where he called new colonists from the Greek motherland. Under the influence of Greek democracy, which gradually gained acceptance in the mother cities, it came around 440 BC. BC nevertheless to overthrow the king. Arkesilaos IV was driven out of Cyrene and fled to Euhesperides. Before he could arm himself from there to counterattack Cyrene, he was murdered.

This independence from the Persian great power is adequately explained by internal Persian conflicts, as a result of which Egypt tried to make itself independent. When during the Persian throne turmoil in 465 BC Chr. Xerxes I was assassinated, it came under the Libyan princes Inaros II. Of Heliopolis, a son of Psammetichus IV., And Amyrtaeus of Sais, again to an uprising. Achaimenes, satrap and prince of the Persian Achaemenid house , arrived with his entire army in Papremis near today's Port Said in a battle in 463 BC. Chr. Killed. Nevertheless, the Persian Empire initially retained the upper hand. Inaros was born in 454 BC. Executed after the suppression of the rebellion.

Relatively undisputed, the Achaemenids ruled Egypt for about half a century, until Amyrtaios settled in 404 BC. Chr. Renounced the Persian empire. At first he only ruled in Lower Egypt, in Upper Egypt he was only recognized four years later. Artaxerxes III. made no fewer than three attempts to conquer the country, because it played a dangerous role for Persia in the uprisings in the empire and in the fight with the Greeks. These, as well as Egyptian militias and Phoenicians, played an important role as kingmakers, as did Libyans, of whom Nectanebo II was able to muster 20,000. Egypt remained independent for more than 60 years.

Finally, Egypt was occupied for the last time by the Persians, which began in 341 BC. BC again subjugated Egypt, when the local rulers also offered fierce resistance. So there was an uprising under Chabbash , probably from 338 to 336 BC. He ruled as pharaoh and at times dominated considerable parts of the country. But the rule of the Persians ended only by the Macedonians under Alexander the Great .

Dareios III. was subject to 333 BC In the battle of Issus against Alexander. This could 332 BC. Take Egypt without a fight. The satrap Mazakes gave him the land and the treasury. 331 BC In BC, the Cyrenaica also came under the rule of Alexander. After the founding of the port city of Alexandria in the western Nile Delta in early 331 BC. BC Alexander moved east. He appointed Peukestas , his bodyguard, along with Balakros to command the troops left behind in Egypt.

Ptolemies, Jewish military settlements, phases of independence, Rome

After his death, the Ptolemies tore Egypt and the Cyrenaica in the course of the Diadoch fights . The satrap Ptolemaios seized Alexander's body and dragged him to the sanctuary in Siwa to have him buried there. Soon the proportion of the Egyptians and Libyans in the cavalry increased sharply, but soon they made up every second man in the infantry, the rest increasingly made up mercenaries. The proportion of the Macedonians fell sharply.

The early Ptolemies achieved a previously impossible integration with a view to the administration and the economy in the empire. At the same time, the Ptolemies built up a sea power that took part in the Diadoch battles in Syria, Asia Minor and Greece. Close trade relations existed with Athens and Cyprus, but the Ptolemies increasingly concentrated on Egypt. The closed currency system applied not only to Egypt, but also to Cyrene. This system of rule was by no means free from strong shocks. So there was an uprising of the soldiers in Lower Egypt from 217 to 197, and intra-dynastic disputes led to civil war-like conditions.

Ophellas (322-308 BC)

322 BC Ptolemy conquered Cyrene. Perdiccas , whom Alexander had installed, was defeated in a battle in the Nile Delta and was killed in 320 BC. Murdered by his own people. Ophellas , also a companion of Alexander the Great, was in the service of Ptolemy I. This commissioned Ophellas in 322 or 321 BC. To eliminate the mercenary leader Thibron, who had stolen the Babylonian tax revenue and established himself in the Cyrenaica. Thibron was defeated and executed in Cyrene. Now the city of Cyrene and the surrounding cities lost their independence after Ophellas smashed the democratic forces that had allied themselves with Thibron. Ptolemy appeared before the end of the conflict in Cyrene and made regulations on the status of the city. He made Ophellas his governor in Cyrenaica. 313/312 BC The Cyrenaica fell briefly from the Ptolemaic Empire, but was recaptured and then placed under its administration again. The uprising started by General Agis in 313 BC. Was suppressed, three more followed.

Apparently between 312 and 309, Ophellas finally made himself independent and sought the establishment of an independent rule. To this end, he allied himself with Agathocles , the tyrant of Syracuse , who was at war against Carthage. When the Carthaginians pressed him in Sicily, he had undertaken a relief offensive, but it had stalled. So he made an alliance with Ophellas. The two agreed to unite their forces against Carthage. After the destruction of the Carthaginian power, Agathocles was to return to Sicily, henceforth rule the island undisturbed and let Ophellas rule over the empire of the Carthaginians. The Carthaginians, on the other hand, not only had trade contacts and a rich hinterland, but they also controlled the Spanish silver deposits until the conquest by Rome in 202 BC. Chr.

Agathocles' son Herakleides remained hostage with Ophellas. As in numerous Diadoch Wars, the military leaders were able to fall back on enormous resources. Ophellas recruited mercenaries in Greece, especially in Athens , who intended to settle with their families in the empire to be conquered. He had a special relationship with Athens as he was married to a noble Athenian named Eurydice, who is said to be descended from Miltiades .

In the summer of 308 he set out with a force of more than 10,000 foot soldiers, 600 mounted soldiers, 100 chariots and 10,000 settlers. After two months they reached the Syracusan's army, but the latter soon accused Ophellas of treason. Ophellas died fighting the troops of Agathocles, his army, which had become leaderless, was integrated into his army. For his part, Agathocles had a good relationship with Ptolemy, whose stepdaughter he later married. The elimination of the ophellas was naturally in the interests of the Egyptian ruler. It is therefore possible that Agathocles, in agreement with Ptolemy, eliminated Ophellas.

Rebellions, expansion into Palestine, increased Jewish settlement

In 308, King Ptolemy easily ensured control of the Cyrenaica and was probably in the region himself. Maybe his son Magas had to put down another rebellion in 301. At the same time the empire expanded into Palestine. Ptolemy I attacked Judaea in 320, 312, 302 and 301 BC. Chr.

Related to this is the settlement of a strong Jewish community in both Egypt and Cyrene. The beginning of the Jewish communities in Libya cannot, however, be precisely defined. The oldest source is a seal, which, however, only roughly relates to the period between the 10th and 4th centuries BC. Can be dated BC. The settlement of Boreion on the border with Tripolitania even claimed to come from the Solomonic period. Even if this suggests Jewish settlers before the Ptolemies, they only came to the country in large numbers with the first rulers of this dynasty. Certainly in connection with the expansion into West Asia, especially after 302, considerable numbers of prisoners came to Egypt, but probably not yet to the likewise rebellious Libya. In addition, Jews came to Egypt because they had fled during the first Syrian war .

Flavius Josephus writes that the Jews were settled there under Ptolemy Lagos to secure the country. These settlers in turn came from Egypt, with Josephus claiming that 120,000 of them alone had been released from prisons there. Another 30,000, according to another source, came from Syrian prisons. So there were at least three waves of settlement, first before the Ptolemies, then around 300 and in the 2nd half of the 2nd century BC. When the first Ptolemaic settlement was analogous to that in Egypt, the Jews were settled as clergy , at least by the middle of the 3rd century at the latest there were Jewish villages of their own. In contrast to Judaea, where slavery was disappearing at that time, it apparently persisted in the diaspora .

As in the rest of the population, child mortality among the settlers was very high; It is striking that around 40% of those buried in cemeteries were under 20 years of age. The mortality rate was apparently particularly high between 16 and 20, with that of men being considerably higher. Getting married at the age of 15 was apparently nothing unusual. It seems that the Ptolemies subordinated the land of the previously free Greek cities to their purposes. In the course of time there was a clear assimilation of the Jews to the Greeks. There was also a Jewish community in Berenike.

Diadoch fights, King Magas of Cyrene (around 283 / 276–250 BC), intra-dynastic battles

The diadoch fights, especially the one with the Seleucids , had serious consequences for both Egypt and Cyrenaica. The Cyrenaica repeatedly achieved a status of independence from Alexandria. The Carthage march of 309/8 was related to the ambition of the tyrant of Syracuse, Agathokles, who took Theoxene, (perhaps) the sister of the governor of Cyrenaica, Magas , as his third wife around 308 . This move, like others by the tyrant, was unsuccessful for him.

Magas, the son of an otherwise unknown Macedonian named Philippos and von Berenike , who lived in 317 BC. In his second marriage Ptolemy I had married, was a half-brother of Ptolemy II. After he had succeeded in suppressing a five-year revolt in Cyrene, he became governor there through the strong intercession of his mother. After the death of his stepfather in 283 BC. He made himself largely independent and ventured around 276 BC. The open rift in which he made himself king of Cyrene.

Magas married Apame , the daughter of the Seleucid king Antiochus I, and used the marriage alliance to conclude an agreement to invade Egypt. He opened hostilities against his half-brother in 274 BC. BC, while Antiochus marched from Palestine . However, Magas had to abandon its activities due to an internal revolt by the Marmaridae, Libyan nomads. At least he managed to gain independence from Cyrene until his death around 250 BC. To maintain. 246 BC The kingdom became Egyptian again.

But the region continued to lead a political life of its own. Ptolemy VIII , the son of Ptolemy V and Cleopatra I , ruled from 170 BC. Together with his brother Ptolemy VI. and his sister Cleopatra II. When the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV , the uncle of the three kings, invaded Egypt, the Alexandrians proclaimed the young Ptolemy VIII together with Cleopatra II as king for a short time. After Antiochus in 169 BC After having withdrawn in the 3rd century BC, the Egyptian king agreed to a joint government with his older brother Philometor and his wife (and sister of both) Cleopatra II. In October 164 BC However, Philometor complained in Rome , threatening to leave Cyrenaica to the Romans, but the Roman Senate gave him no support.

A year later the brothers agreed on a division of power, with Ptolemy VIII receiving the Cyrenaica. But the brothers continued to fight in Cyprus, an attack was carried out on the ruler of Cyrenaica, who was finally captured. But his brother spared him, even offered him the hand of his daughter Cleopatra Thea and sent him back to the Cyrenaica. When Philometor 145 BC Died on a campaign, Cleopatra II proclaimed her son Ptolemy VII as his successor; Ptolemy VIII, however, returned to Egypt and proposed a joint government and marriage to his sister Cleopatra. He ascended the throne as Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II, a name that goes back to his ancestor Ptolemy III. should remember.

There were mass expulsions of Jews and intellectuals from Alexandria who had supported Philometor. Josephus mentions a failed massacre of Jews using fighting elephants. Polybios states that almost the entire Greek population is said to have been expelled from Alexandria. However, there is no evidence of a correspondingly brutal course of action against the Jews of Cyrenaica. From 146 BC. If one interprets the coins correctly, there were close trade contacts with Judaea, Libyan Jews can still be found in Jaffa in the 2nd century .

Further dynastic disputes led to 132/131 BC. To a civil war. Cleopatra II offered the Egyptian throne to Demetrios II to Nicator , who, however, only got as far as Pelusion with his army ; 127 BC Cleopatra fled to Syria, while Alexandria fought for another year.

Increasing dominance of Rome

But by this time Rome had already risen to guarantee the continued existence of the Ptolemaic Empire. After the Roman victory over Macedonia, Gaius Popillius Laenas went to Alexandria to deliver an ultimatum to the Seleucid Antiochus IV that demanded the immediate withdrawal from occupied Egypt. With his harsh manner, he induced the Seleucid king to accept the Roman demand (Polybios 29:27; day of Eleusis ).

The son of Ptolemy VIII, Ptolemy Apion could only be 105/101 BC. In his will, he left his kingdom of the Roman Republic as he died without an heir. 96 BC BC Rome acquired the Cyrenaica. 30 BC BC Egypt also became Roman.

Carthage and Tripolitania, Rome

In Tripolitania , the western part, the Phoenicians founded the cities of Sabratha , Oea ( Tripoli ) and Leptis Magna , but they were founded in the 6th century BC. Came under the control of Carthage and until 200 BC. Belonged to the Carthaginian province. Subsequently, this part of the country was incorporated into the Kingdom of Numidia , before it was 46 BC. Became a Roman province.

Guarantors

Herodotus names the Makers, Gindans and Lotophages in Tripolitania . The Garamanten described by him lived mainly around the city of Garama in Fezzan . According to him, they used chariots, with their predominance in the 1st century BC. In northern Sudan. They raised cattle and sheep, but also planted wheat. They buried their dead in extensive necropolises, the tombs were often small pyramids. Everyday objects were added to the dead.

The Garamanten lived in tents, simple huts or in troglodytes , as in Tripolitania. Herodotus ( Historien 4.138) referred to the latter as Trogodytai Aithiopes (Τρωγοδύται Αἰθίοπες), with which he referred to a reptile-eating tribe in southern Libya, possibly the Tubu . From the incorrect derivation trogle (τρώγλη "cave") and dynai (δῦναι "immerse") the name was later transferred to all types of cave-dwelling peoples (Strabon Geographika 1.42). According to Herodotus, polygamy prevailed and the line of ancestors ran through the mothers. Metals were introduced, metalworking was not practiced, and the potter's wheel was not yet used in Herodotus' time. Offerings were made to the sun and moon. In the 6th century, the cult of Amun-Re, which came from Egypt, grew stronger.

20 BC The proconsul Lucius Cornelius Balbus Minor initiated a military expedition against the Garamanten, probably under the pretext that they were threatening the Roman coastal cities (the only source for this is Pliny nat. Hist. 5. 35-37). However, there was no submission, but an alliance with "Phazania", which from then on supplied olive oil and wine. Balbus received a triumphal procession for this on March 27 of the following year . It also later became apparent that the Garamanten led an independent policy towards Rome. When the Gaetuler Tacfarinas led an uprising against the Roman occupation in North Africa from 17 to 24 AD , which was supported by numerous Libyan tribes, the Garamante king kept the booty for him. The last time in AD 70 there was fighting between Rome and the Garamanten in Fessan. These interfered in border disputes between Oea and Leptis (minor).

Around 150 AD Garama (now Garma) had about 4,000 inhabitants. This was only possible on the basis of a complicated irrigation system that used the limited water resources sparingly. The Garamanten obtained the manpower they needed through slave hunts. The warriors are depicted in rock paintings on horse-drawn chariots, armed with shields, bows and spears. It is unclear whether they had adopted this chariot fighting technique from the eastern Mediterranean, for example by Hyksos . In any case, their forays extended into northern Chad and the Air region in northern Niger. However, the wagons were not only used for combat, they were also used in agriculture and for transporting people. Herodotus reports that the Greeks took over the chariot with four horses from the Garamanten.

The language is likely to have been related to that of the Tuareg, the Garamanten also developed their own script, which, however, has not been deciphered. The underground water reservoirs were tapped using water tunnels, the Foggara system or Qanat . This system possibly got there with the Persian conquest of Egypt (525 BC) and spread further west. Qanatsysteme passed around in the oasis Kharga , but also in Morocco.

The decline began in the 4th century, possibly as a result of the drying up of the waterholes that were necessary to maintain the horse and ox-farmed economy and to maintain the corresponding trade. In the second half of the 6th century the Garamanten adopted Christianity, in the 7th century Islam.

The coastal fringe as part of the Roman Empire

In the 1st century BC BC the Roman Empire conquered Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. Only the Garamanten des Fezzan in the south could maintain their independence. The Roman rule intensified the exchange of goods, especially since piracy was fought by Rome. The cities in particular benefited from the flourishing agriculture, which was now part of a much larger market encompassing the entire Mediterranean region, and from the trans-Saharan trade with the Sahel . The high point of this development marked the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus (190-211), who expanded and adorned his native city Leptis Magna and the other cities in the region. This huge construction work brought lasting impulses to the local economy. Probably during his reign, a small military outpost, the Cidamus castle , was built to monitor the flow of goods beyond the borders of Rome. The fort can only be recorded in writing, however.

Division into provinces, Berber tribes, establishment and relocation of the Limes Tripolitanus

Under Augustus the double province of Creta et Cyrene was created, so that Cyrenaica was administered from the Cretan Gortyn . The province was headed by a proconsul who was chosen by the senate from among the former praetors .

During the provincial reform of Emperor Diocletian , Crete and Cyrene were divided into the three independent provinces Creta , Libya superior and Libya inferior . The Praefectus praetorio per Orientem were now subordinate to the dioceses of Oriens , which included Egypt, the Levant, Cilicia and Isauria , then Pontica (northern and eastern Anatolia) and Asiana (southern and western Anatolia). Around 380/395 Theodosius I divided the provinces Libya superior, Libya inferior, Thebais , Aegyptus , Arcadia and Augustamnica from the Dioecesis Orientis and established the Dioecesis Aegypti from these provinces . As vicarius of the new diocese, he installed his son Arcadius . The number of prefectures was increased to five.

The inhabitants of Marmarica in Libya inferior called the Romans Marmaridae . According to Pseudo-Skylax , their settlement area extended westward from Apis in Egypt. According to Florus , they were subjugated by the Romans at the turn of the time by Publius Sulpicius Quirinius in the course of the campaign against the Garamanten . The Historia Augusta reports of successful battles of the Probus, whereby Tenagino Probus , then Praefectus Aegypti , and not the later Roman emperor Probus , should be meant. In late antiquity the area was also known as Libya Sicca , in contrast to the Cyrenaica called Libya superior.

At the end of the 2nd century Rome felt compelled to secure its southern border with a chain of fortresses. The legate Quintus Anicius Faustus was commissioned to do this . The Limes Tripolitanus was built between 197 and 201 and was continuously expanded. Ghirza became an important trading center. While the economy of Cyrenaica was based on wine, oil and horses, in Tripolitania it was also based on olive oil, but here the cultivation of wheat and the slave trade played a greater role.

When an uprising began in Upper Egypt in 292 and Alexandria rose against the Romans two years later, Emperor Diocletian recaptured the country in 295. South of Leptis Magna, it was the Nasamones, a Berber pastoral people who lived between the Great Syrte and Audschila in the time of Herodotus , who threatened the city. According to Pliny the Elder , they had driven the psylli from the Great Syrte (Nat. Hist. 7.14), where they grazed their cattle while they used the date palms of the southern oases. Herodotus (2.32-33) reports that they visited the Amun shrine in Siwa and maintained contacts as far as Sudan . According to him, the dead were buried seated.

When the Roman collectors tried to collect taxes, they killed them. They first defeated the Legio III Augusta under the leadership of Gnaeus Suellius Flaccus in 285 or 286, but in return they were almost wiped out. This legion was dissolved in 238, but was re-established in 253 to repel attacks by the Quinquagentiani, the "five tribes", and the Fraxinenses, a federation of Berber tribes. The vexillations spread over the forts of the Limes Tripolitanus and various oases were concentrated until 290 and advanced outposts were given up as planned despite the victory. Ever since the Severans it was customary for recruitment to take place from the respective province and the “camp offspring”, so that about 95% of the III Augusta consisted of “Africans”. After 300 the legion was used against an insurgent governor, at which time it was moved from Lambaesis in what is now Algeria to an unknown camp in the region.

The last but also the most violent persecution of Christians took place during Diocletian's reign. According to Prokop, Audschila (Augila) remained true to the traditional beliefs until the 6th century. It was Christianized under Justinian I , after the reconquest of the Vandal Empire.

Legal relationships, municipality, colony

From 212 onwards, all cities in the empire had at least the rank of municipium , which, in addition to legal advantages, entailed considerable financial burdens. Every male resident between 14 and 60 had to pay an annual fee. The small group of Roman citizens was exempt from this, however, the upper classes (metropolites) paid a reduced tax.

The security of the residents, who were concentrated mainly in the cities, depended on the governors who were appropriately equipped. One of them, Romanus , who held the office of comes Africae from 364 to 373, was considered particularly corrupt. If one follows the late antique historian Ammianus Marcellinus , then he did not shy away from being paid by the population of the province of Africa Tripolitana, that is, above all from Leptis Magna, for taking action against tribes that attacked Roman cities from the hinterland. It was above all the Austoriani who raided the area around the city, which had around 80,000 inhabitants, as it is still often called today. However, the triggering process was different: under Jovian , one of their relatives named Stachao was executed, which the Austoriani viewed as injustice and therefore took revenge. Thereupon, at the request of the city Romanus, moved towards Leptis with an army, but he demanded 4,000 camels from the city, without which he could not advance. The city, which could not provide him with such a huge flock, had to endure his presence for 40 days before he left without a single blow of the sword. One complaint to the emperor led to nothing, as did another. A third delegation, which reached the emperor in Trier , had the consequence that the indignant emperor Valentinian sent a notary named Palladius, who should at least settle the arrears of the garrison. In the meantime the Austoriani besieged the metropolis, which had never been besieged before, in a third raid, albeit unsuccessfully, for eight days. Romanus gave Palladius larger sums of money, but when Palladius threatened to send a report on his corrupt and greedy behavior to the emperor, he in turn threatened to report him to court for bribery. So the notary was forced to write a positive report. Valentinian then had the complainants sentenced to death by the City of Leptis for making false accusations. Only years later did the discovery of a letter lead to the truth that Palladius had lied to the emperor. This committed suicide, Romanus had to appear in Milan . From this point on we don't hear from him anymore.

370 or 372 to 375, the Mauritanian prince's son Firmus , against whom Romanus had intrigued, rebelled . Against Romanus and the rebelling Firmus, Emperor Valentinian sent his general Flavius Theodosius , the father of the later Emperor Theodosius I. He refused the submission offered by Firmus. After the military defeat, Firmus took his own life.

These cases show that it was not mere predatory greed of nomads that drove them into the uprisings and raids, but the existential threat posed by corrupt representatives of imperial power, who were heard much more easily at the distant imperial court than even the envoys from the largest cities , let alone the representatives of the Berber tribes.

This system, which was geared towards Roman needs and was dominated by the Greco-Roman culture, especially in the cities, from which the headquarters, however, increasingly distanced itself, was opposed to a Berber system, which only had the option of complete autonomy. The state development of the Berbers, which began in the 5th century BC. Had begun, the Romans had interrupted several wars earlier. However, there were repeated uprisings, such as around 45 AD, which ended mainly because Africans gained influence in the highest circles. Lucius Quitus, a Berber, was a member of the Senate, and Septimius Severus from Tripolitania even became emperor. But then a reversal of the trend, accompanied by strong militarization, set in. When the Donatists emerged, especially in the 4th century, they also supported insurgent Berbers, such as 372 to 376 Firmus or 396 his brother Gildon.

As in the rest of the empire, the situation of farmers and landowners changed drastically in rural areas. Imperial laws, presumably on the initiative of the large landowners, created the prerequisites for transferring almost unlimited power of disposition and police power to local masters, whose growing economic units were thereby increasingly isolated from state influence. The rural population was initially forced to cultivate the land and taxes (tributum) to be paid. Until the 5th century, the people who worked the land were often tied to their land while their property belonged to their master, but after three decades in this legal status others could take their mobile property or their property into their own possession. Under Emperor Justinian I there was no longer any distinction between free and unfree colonies . Colons and unfree were now used identically to describe arable farmers who were tied to the clod and had no free property.

However, this development began in the 3rd century at the latest. Since Constantine the Great , gentlemen have been allowed to chain fugitive colonies who had disappeared less than 30 years ago. Since 365 it has been forbidden for the colonists to dispose of their actual possessions, probably primarily tools. Since 371 the gentlemen were allowed to collect the taxes from the colonies themselves. Finally, in 396, the farmers lost the right to sue their master.

Jewish community, uprising (115–118)

The Jewish communities consisted primarily of farmers and soldiers, but there are also artisans, as well as limited trade. Parishes can be made probable in Berenike, Cyrene, Ptolemais, Apollonia, Teucheira and possibly Barka, but also outside the Pentapolis apparently parishes existed, which probably also included the surrounding area. Apparently there was a synagogue by the sea in Berenike . On special holidays the several hundred, perhaps even several thousand members of the community gathered in an “ amphitheater ” that probably belonged to it and that was built around 25 BC. Was built. You don't have to imagine an elliptical building, however, the 'ampho' means nothing other than 'on both sides'.

During the Roman campaign against the Garamanten in the years 20 to 2 BC. Apparently military settlers from Syria came to Cyrenaica, including some Jews; It should therefore come as no surprise that Flavius Josephus uses the military term syntagmata to describe the communities. These settlers sometimes transferred the name of their place of origin to the new settlement, such as in the case of Magdalis in the Martuba region, possibly also from Targhuna, which perhaps went back to Trachon in Auranitis , Syria . The largest community was probably in Cyrene, where in the year 73 AD alone 3,000 relatively wealthy and 2,000 residents were considered to be poor. According to Flavius Josephus, they had been striving for legal equality with the other townspeople since Augustus; the Alexandrians had already received this equality through Alexander the Great. However, the Jewish communities of Cyrenaica were separate bodies from the urban communities. But at least some Jews gained citizenship, around the turn of the century Jews obtained degrees from the Gymnasium of Cyrene. A few even got promoted to local administrations.

A separate internal organization of the communities goes back to Ptolemaic times, it is under the name politeuma for the years 8 BC. As well as 24/25 and 56 AD in Berenike. The Romans accepted such self-organization when it served no political ends. The Jewish communities ensured, for example, that collective contributions were collected for the Temple of Jerusalem and the cultivation of the faith, the establishment of their own cemeteries and the maintenance of an internal judiciary. When performing public duties, they neither had to appear in court on Jewish holidays, nor ritually honor the Roman gods or the emperor.

As early as the 3rd century BC Jews maintained contact with Libyans. So one of their kings took Arkesilaos III. , a man named Aladdeir, king of Barka, uses the Jewish name Eleazar. His descendants lived in Barka. In the Maghreb, entire tribes later confessed to the Jewish faith, but this has not been proven for the Libyan tribes. Arab traditions suggest that there were Jewish traditions in various villages, such as in Gubba , Negharnes or Messa, but also Ras e-Sabbat or Kaf e-Sabbat north of Barka.

During the civil war from 91 to 82 BC BC, which ended in Cyrene with an aristocratic government under Arataphila, there was a Jewish uprising or internal disputes (stasis), of which nothing is known. Perhaps there was a connection to the uprising of the lower social classes in the Egyptian Thebais from 88 BC. The wars of King Mithridates caused violent social uprisings in other places in the eastern Mediterranean as well, and civil wars in Rome. The piracy reached unprecedented proportions. At the same time, Roman rule brought an end to the control of the Ptolemaic Libyan Arch, so that a Libyan king named Anabus could ally himself with the Pentapolis. Perhaps as a result the Libyan nomads, who probably enjoyed greater freedom of movement with their herds, came into conflict with the Jewish farmers. The latter had already come under pressure from the Ptolemaic policy of expanding state goods at the expense of small and medium-sized peasants. With the Romans, the state became ager publicus , but possibly also just the personal property of the last Ptolemaic ruler. The Greek residents paid a levy, the Libyans a grazing levy.

The economic depression of the Cyrenaica took Rome as a pretext in 75/74 BC. To take full possession of the land and establish it as a province together with Crete. Apparently they wanted to put an end to conflicts that had led to the flight of peasants; to 2 v. BC Rome managed to break the alliance between the cities and the southern nomads for good. The land was redistributed, and publicani settled and collected taxes. A system of exploitation developed in an alliance with the Roman office holders in the cities, which Augustus 7/6 BC. Chr. To intervene. He allowed those concerned to go to court. The system of transhumance promoted by the publicani, who collected taxes on wool, for example, apparently destroyed the local economy, because the exploitation by the publicani was apparently no longer worthwhile from the middle of the 1st century. Lucius Acilius Strabo was used as a kind of mediator in 59, but in the end Emperor Nero personally decided on the question of whether the land belonged to Rome or to the inhabitants of Cyrenaica after the Senate was unable to decide. He left their land to the residents of the countryside as a concession, although the previous owners were probably turned away. This restoration of Roman state property can also be archaeologically proven by means of three boundary stones that expressly mention this. With this, the older settlers, including the Jews, had finally lost their protection from attacks by the Libyans, the protection of the Ptolemaic kings, and above all they were defenselessly exposed to the Roman conductores . This paved the way for the emergence of a landless proletariat. Perhaps under Emperor Trajan , Hyginus Gromaticus toured the country, a surveyor who did not miss the distribution of property.

In 115, while Trajan was waging his war of conquest in the east, a widespread Jewish rebellion broke out in the eastern diaspora countries . It soon developed into an open war that spread to Cyrenaica and Libya, Egypt, Mesopotamia and Cyprus. This war was preceded by skirmishes between Jews and Christians in Alexandria and Cyrene, but it was soon directed against Rome. The fighting was so intense that cities were devastated even after three decades. In addition, inscriptions from the time of Emperor Hadrian indicate that the road between Cyrene and Apollonia "was devastated and made unusable during the Jewish uprising". Even if Cassius Dio (Roman History, LXVIII, 32) 100 years later certainly tried to pile up every imaginable accusation of the inhumanity of the insurgents, as often happened between political-religious opponents, his description probably also reflects the memory of the brutality of the Disputes reflect: “In the meantime the Jews of Cyrenaica had made a certain Andrew their leader and destroyed both Romans and Greeks. They ate the flesh of their victims, made girdles of entrails, smeared themselves with blood, and clothed themselves in the skins; many saw them from top to bottom, others threw them before wild animals, and still others forced them to fight as gladiators. In total, two hundred and twenty thousand people died. ”In the end, the emperors saw themselves compelled to bring numerous colonists into the country to compensate for the human losses.

Apparently the non-Greek peasants supported the Jews against Rome, because where they did not, they were showered with praise. The Jewish armies moved to Egypt, but were eventually subject to the legions of Emperor Hadrian in 118. The leader of the uprising was a Jew named Andrew or Luke; he probably had both a Hebrew and a Greek name. Since he is referred to as a king, he will be seen as a messianic pretender , comparable to Simon bar Kochba , the leader in the last great uprising of the Jews from 132 to 135. In Cyrene, the Greek temples in particular seem to have been the target of destruction. The temples of Apollo , Zeus , Dioscuri , Demeter , Artemis and Isis , but also the symbols of Roman rule such as the Caesareum , the basilica and the thermal baths were destroyed or badly damaged. Newly erected buildings and milestones give the Jewish uprising ( tumultus Iudaicus ) as the reason for the renovation . The Jewish community did not disappear after the fighting, but the time of its great influence was over after Roman rule brought it a long period of economic decline and the loss of its land rights.

Christianization, religious conflicts

With the relocation of the imperial capital from Rome to Byzantium, Christianity gradually became the dominant religion in the Roman Empire, and even the state religion in 380. It should have spread from Egypt, where the evangelist Mark was venerated with pilgrimages at the latest in the 4th century. According to Coptic tradition, Markus even came from Cyrene (or the Kairuan area in Tunisia), from where his Jewish parents fled to Palestine for fear of Berber attacks. Accordingly, he went from Palestine to Alexandria in AD 48. With the increasing privilege of the state, which included tax exemption, a steeper church hierarchy emerged. The bishops in the respective metropolis of the provinces became archbishops from 325, to whom the other bishops of the province owed obedience. Below the Bishop plane found deacons and deaconesses , elders and lecturers , were added gravedigger doorkeeper Protopresbyter and subdeacons. The clergy was the only class to which all social classes had access, even if not everyone could rise to the highest positions in the most important church centers and the higher classes probably did not strive for a diocese in less respected areas. The Clergy on the estates of the landlords put residents who are tenant farmers .

Synesius of Cyrene (around 370 to after 412), from 410 or 411 Bishop of Ptolemais , received his education in Alexandria. As a Neoplatonist, he worshiped Hypatia , the last pagan Neoplatonist. Synesios was made bishop of Theophilus, Patriarch of Alexandria in 411. Since 325 the ecclesiastical province belonged to the capital of Egypt. The ecclesiastical province is still subordinate to the Coptic Pope in legal matters. As a Platonist, Synesios held fast to his conviction of the eternity of the world and the pre-existence of the soul . He rejected the resurrection of the flesh, ecclesiastical dogmas which he found unacceptable as a philosopher, he considered myths that were only intended for the foolish, he remained married. Against the praeses Andronicus, whom he accused of serious crimes, he went with excommunication before, Andronicus was deposed. Synesios stood up for the overthrown governor of the Patriarch Theophilos.

After the division of the Roman Empire in 395, Tripolitania was annexed to the Western Roman Empire , Cyrenaica to the Eastern Roman Empire . Greek finally gained the upper hand over Latin as the official language in the east of the empire. Last pagan cult acts are documented under Justinian I.

The religious conflicts continued in the east of the empire, but now it was more a question of theological disputes within Christianity, revolving around Christological questions. Theophilus died in 412, his successor was Cyril , one of the most powerful churchmen of his time, who was able to enforce his theological positions bindingly for the imperial church at the ecumenical council of Ephesus in 431 and is still considered the most important founder figure of the Miaphysites . Cyrill's successor Dioskur , who took over the patriarchal office in 444, was initially able to assert himself with his Monophysite teaching at the so-called Synod of Robbers of Ephesus in 449 . But only two years later there was a split at the fourth ecumenical council in Chalcedon : Pope Leo the Great rejected the Monophysite doctrine, and the majority of the council and Emperor Markian endorsed this position. However, the majority of the Egyptians stuck to the rejection of the council resolutions, which repeatedly led to tensions between Egypt and Constantinople.

Monophysitism arose against the background of rivalries between the Patriarchate of Alexandria and that of Antioch . In addition to Egypt, monophysitism was also gaining ground in Syria. In the 480s, the emperors tried to implement a compromise solution formulated in the Henoticon , which ignored all disputes between “Orthodox” and “Monophysite” Christians and ignored the resolutions of Chalcedon; but this attempt failed and instead of an agreement with the Monophysites only led to the 30-year-long Akakian schism with the Roman church (until 519). The 2nd Council of Constantinople in 553 could not reach an agreement either. The same applied to the short-lived promotion of the Monophysitic special current of aphthartodocetism by Emperor Justinian I.

In the early 7th century, monotheleticism was developed as an attempt at a compromise solution . According to this, Jesus has a divine and a human nature. Divine and human nature, however, have only one common will in it. This attempt to bridge the gap between Monophysitism and the position of Chalcedon also failed. Monotheletism was rejected in the Reich Church after Maximus Confessor's objection . Already from around 640 AD he was polemic against monotheletism, which was often brought with them by refugees from the eastern Roman areas conquered by the Arabs. In 645 he was able to convince the former patriarch of Constantinople Pyrrhus of his dyotheletic teaching in a public disputation . The two doctrines agreed that Jesus Christ had two natures, namely a divine and a human, but in Constantinople at that time the belief in only one will or goal prevailed, while Carthage and Rome also believed in two separate wills represented.

While the religious conflicts alienated the Monophysites from Constantinople, the regional conflicts continued. Emperor Markian fought during his reign (450–457) Nubians and Blemmyes , from the west the (Arian) Vandals threatened Tripolitania and Cyrenaica with their fleet, in the first half of the 7th century it was Persians and Muslim Arabs.

Vandals in Tripolitania, reconquest by the East Current, expansion of the Berbers

In the course of the Great Migration , 429 maybe 50,000 (Prokop) or 80,000 Vandals and Alans from southern Spain to Africa. This corresponded to a force of about 10,000 to 15,000 men. Some Berber tribes supported them, as did supporters of Donatism , who hoped for protection from persecution by the Roman state church. In 439 the Vandals conquered Carthage , with the fleet stationed there falling into their hands. With it the Vandals succeeded in conquering Sardinia , Corsica and the Balearic Islands and, above all, they sacked Rome in 455. For the first time , King Geiseric resorted to Moors, i.e. Berbers, of whom some groups in turn gained increasing independence in the border area to the Sahara.

Vandals invaded Tripolitania in 450, but the balance of power there is unclear. In 456 Rome attempted a counterattack, but it got stuck. A large-scale attempt by western and eastern Roman troops to retake Africa failed in 468. Another was made in 470, possibly by land via Tripolitania. But this also failed.

The Vandals hung the Arianism to, a faith that in the first Council of Nicaea to heresy had been declared. Property of the Catholic Church was confiscated in its sphere of influence. The relatively small group of conquerors sealed themselves off from the provincial Roman subjects. At the same time, the Vandal and Alan warriors received estates, for which part of the property of the provincial Roman population was divided. The colonies tied to the ground may only have changed the masters; the imperial goods were probably simply transformed into royal goods and served the now ruling dynasty.

The successor of the founder of the empire, Geiserich, his eldest son Hunerich , had around 5000 Catholic clergy arrested at the beginning of 483 and deported to the south of the Byzacena , then further south to the Moorish area. In two edicts , Hunerich closed all Catholic churches and called for a conversion to Arianism, similar to what earlier imperial edicts against heretics had done. He forced the bishops to take an oath on his son Hilderich as heir to the throne, but then made them colonists for violating the biblical ban on oaths. Those who refused to take the oath were exiled to Corsica and subjected to heavy physical labor. Despite some successes, the Vandals lost their reputation, mainly because they found no means against the Berbers, who occupied Vandal territory piece by piece. King Hilderic also distanced himself from Arianism. Moors under the leadership of a certain Antala defeated a vandal army in eastern Tunisia. On June 15, 530, a conspiracy in which a great-grandson of Geiseric named Gelimer played a central role, the king , overthrew . At first he tried to put down revolts, including in Sardinia and Tripolitania.

Gelimer was viewed by Ostrom as a usurper , prepared for his fall. In 533 16,000 men landed in Africa under the leadership of the Eastern Roman general Belisarius . The realm of the Vandals went under after the Battle of Tricamarum . King Gelimer fled to Bulla Regia, about 160 km west of Carthage. His brother Tzazon, the governor of Sardinia, joined him at the beginning of December 533, but he was killed together with 3,000 vandals in the said battle, Gelimer fled to the Berbers, but was soon captured. Carthage fell to Belisarius on September 15, 533, but it was not until 546 that the conquest could finally be completed.

Tripolitania also became part of the Eastern Roman Empire again from 533. After the destruction by the vandals and after attacks by Laguatan (Lwatae) nomads, Olbia was re-founded as Polis Nea Theodorias by Emperor Justinian I in 539. The foundation was in honor of the imperial wife Theodora I , who was her youth in the near future Apollonia. The entire region belonged to the exarchate of Carthage at the end of the 6th century .

Carthage was initially the seat of an Eastern Roman governor, a Praetorian prefect who was responsible for civil affairs and to whom six governors were subordinate. For the military sector, a Magister militum was appointed for imperial North Africa, to which four generals were subordinate.

The North African Church achieved the renewal of its old privileges as early as 535 and at the same time resisted the increasing influence of the Church of Constantinople. The bishop of Carthage received the dignity of a metropolitan from the emperor in 535.

The binding of the peasants to the soil, which was already legal practice in the Eastern Roman Empire, was now transferred to the former Vandal Empire and therefore also to Tripolitania. For example, Emperor Justin II transferred a corresponding novella from Emperor Justinian from 540, which was valid for Illyricum , to Africa in 570 . 582 this transfer was confirmed. This amendment, which established the status of the children of colons and free, was transferred to the province on the initiative of the Bishop of Carthage Publianus and the landowners of the Proconsularis . The province was reorganized under Emperor Maurikios around 590 as the exarchate of Carthage, which, similar to Italy, combined military and civil powers, which was otherwise unusual in late antiquity .

Procopius reports that the residents of Ghadames were allies of Rome from ancient times and that they renewed their treaties during the reign of Emperor Justinian I. On the other hand, the Louata, nomads who came from Libya and repeatedly pushed far towards Carthage, presented a particular danger.

Brief Persian rule (618 / 619–630)

For centuries, the Romans and Persian Sassanids have repeatedly got into military conflicts, which mostly focused on border disputes. However, the Roman-Persian battles of the 7th century were ultimately characterized by the will to defeat the enemy completely, to conquer his country, no longer just to gain territories. Chosrau II (590–628) began between 603 and 627 to systematically occupy Eastern Roman territory. He proclaimed himself the avenger of Maurikios, murdered by Herakleios' predecessor Phocas, whose protégé he had become when he had stayed at the court in Constantinople for four years. He now opened a war of conquest against Ostrom, in which the Levant and parts of Asia Minor fell to him. 614 Jerusalem fell, 617 the Sassanids occupied Egypt, 618 Cyrenaica, 619 Tripolitania.

But after he had overthrown his predecessor from Carthage in Constantinople in 610, Emperor Herakleios went on the offensive. An embassy to Chosrau II received no answer; he was unwilling to give up the advantages he had already gained. In 617 Herakleios considered moving the capital of the empire from Constantinople to Carthage. However, he attacked the Persians in their heartland from 623 and was not distracted by attacks by the Avars and Slavs on the capital, which they besieged in 626. Herakleios gathered more troops in Lazika on the Black Sea and again made contact with the Turks, who in turn attacked the Persians. The Persian army was defeated at Niniveh, Herakleios approached the capital Ctesiphon. Ultimately, the great king in 629 or 630 was forced to sign a peace treaty and withdraw his troops from all conquered areas.

Arab conquest and Islamization (from 643), Berber resistance

A few years after the end of the war between Eastern Byzantium and the Persian Empire, the slow triumphant advance of the new religion of Islam , which was based on the sword mission, came from the Arabian Peninsula, began . However, the individuals were not forced to evangelize, but they had to accept social disadvantages if they did not want to convert. They followed on from the religiously motivated readiness to fight, which had been sparked for almost two decades by the propaganda apparatus of the two great empires and which had increasingly spread to almost the entire Mediterranean and the areas bordering it to the east. At the same time, Islam encountered a rugged, often irreconcilably hostile Christian world, so that the Arabs could definitely be seen as liberators.

Shortly after the Muslim conquest of Egypt (639-642), Cyrenaica was occupied between November / December 642 and March 643, and then, three months later at the earliest, Tripolitania was occupied. As Amr, the administrative director, wrote, his troops were only nine days' march from Ifrīqiya , what is now Tunisia. Oea withstood the siege for a month, and Sabrata was also stormed. Due to the forays of the Arabs into the Sahara, the empire of the Garamanten in Fezzan finally fell. The Berber resistance was broken in 670 and the country was Islamized. In contrast to Christians and Jews, the converts did not pay any additional levy as required by the Koran.

The Lawata paid their taxes to Misr (Egypt), apparently not needing a collector, as they did not pay their taxes personally but collectively. This took place in a form that was also controversial among Arab legal scholars, namely the sale of women and children to the conquerors. Such a case of collective taxes is only known in Armenia , so it could be a particularly brutal punishment, perhaps for an uprising. The most important sources on the phase of the subjugation of the Berbers and their conversion to Islam are the works of Ibn Lahi'a († 790) and Al-layth ibn Sa'd († 791). A few decades after the conquest, Greek was replaced by Arabic as the administrative language. Despite severe setbacks and internal disputes, the Maghreb was conquered from around 670 onwards , and until 705, like all areas of Islamic North Africa, it was under the governor of Egypt.

The ruling dynasty was initially that of the Umayyads , then (from 750) they were replaced by the Abbasids , while the Iberian peninsula split off from the empire that had emerged within a few decades under the only surviving Umayyad. But the conquest of the hinterland against the resistance of the Berbers made slow progress. Queen al-Kahina even managed to push the Arabs back as far as Tripolitania, and the governor there fled to Barka. It was not until 702 that she was defeated in a battle.

After stubborn resistance, most of the Berbers converted to Islam, mainly by joining the armed forces of the Arabs; culturally, however, they found no recognition, because the new masters viewed them with as much contempt as the Greeks and Romans once had of their neighbors, and they also adopted the Greek word barbaric for those who had not learned their language. Therefore the Imazighen (singular: Amazigh) are still called Berbers today . They were paid less in the army and their wives were sometimes enslaved, as with subjugated peoples. Only Umar II (717–720) forbade this practice and sent Muslim scholars to convert the Imazighen. In the Ribats Although religious schools have been set up, but there are numerous Berber joined the denomination of the Kharijites , which proclaimed the equality of all Muslims regardless of their race or social class.

Resentment against the Umayyad rule increased. As early as 740-742 there was a first uprising of the Kharijites near Tangier under the Berber Maysara . Some Berber groups made themselves independent, in 742 they controlled all of Algeria and threatened Kairuan in Tunisia. At the same time, a moderate branch of the Kharijites came to power in Tripolitania. The Lawata from the Kyrenaika migrated westward in 757/758 together with Nafusa and Nafzawa and joined the Ibāḍiyyah Tripolitania. Although the coastal cities were quickly subjugated, the resistance of the Berbers in Jabal Nafusa continued when the tribes under Abu l-Khattab al-Maafiri also joined the Kharijite Ibadis .

The end of the Umayyad rule in Tunisia had already begun in 747. The descendants of Uqbah ibn Nāfi, who had become a legendary hero and conqueror, the Fihrids , used the uprising of the Abbasids in the core kingdom to make Ifrīqiyyah independent. Although they now ruled the north of the country, the Warfajūma Berbers ruled the south in league with moderate Kharijites. They succeeded in conquering the north in 756. But another moderate Kharijite group, the Ibāḍiyyah from Tripolitania, proclaimed an imam who saw himself on the same level as the caliph and conquered Tunisia in 758. In the end, the Abbasids succeeded in conquering large parts of the rebellious territory in 761, if only in Tripolitania, Tunisia and Eastern Algeria. Once again in 771/772 the Berbers joined the rebellious Kharijites , their defeat in 772 led to the downfall of the Malzūza- Berbers. Ibrāhīm ibn al-Aghlab, who commanded the army in eastern Algeria and founded the Aghlabid dynasty , gradually made the country independent, but still formally recognized the rule of the Abbasids.

The Abbasids raised Oea to the new center of Tripolitania, which soon took the name of the Tripoli landscape . It was now the westernmost area still belonging to the great empire.

Dissolution of the Arab Empire, regional powers, Aghlabids in Tripolitania (740-800)