Sheschonq I.

| Name of Sheschonq I. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horus name |

K3-nḫt-mrj-Rˁ sḫˁj = fm-nsw-r-sm3-t3wj Strong bull, lover of Re, when he goes out as king around the to unite both countries |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

Hḏ-ḫpr-Rˁ stp.n-Rˁ With a shining figure, a Re, chosen by Re |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

(Scheschonq meri Amun netjer heqa Iunu) Ššnq mrj Jmn nṯr hq3 Iwnw Scheschonq, loved by Amun , divine ruler of Heliopolis |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Greek for Manetho |

Sesonchis | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

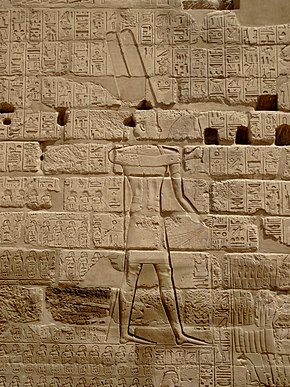

Scheschonq I as a conqueror (temple wall in Karnak) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Scheschonq I (also Shoshenk I ; Assyrian Šusanqu, Schusanqu , Susinqu ; Hebrew Šišak, Schischak, Šušak, Shuschak ) was the ancient Egyptian founder and 1st Pharaoh (King) of the 22nd Dynasty ( Third Intermediate Period ) and ruled around 946 to 924 v. After his uncle Osochor, he is the second Libyan ruler on the throne of the pharaohs.

Title

- Nebti name : The one in the double crown appears like Harsiese ("Horus, son of Isis"), who satisfies the gods with the mate

- Gold name : With mighty power that strikes the Nine Bows (the enemies of Egypt), great in victories in all countries

family

Scheschonq I was the son of Namilt (Lamitu) and Tanetsepeh. From his marriages with Karama (I.) and Penreschnes he had at least four children: his sons were Osorkon I. , Namilt (I.) (Lamitu), whom he made ruler of Herakleopolis , and Iupet , whom he was high priest of Amun installed. His daughter Taschepenbastet was married to Djedthotiuefanch, the third priest of Amun in the temple of Karnak .

Domination

For the first four years, Scheschonq I was only recognized as a pharaoh in Lower Egypt. In an inscription in the priestly annals of Karnak about the second year of his reign, Scheschonq I is only referred to as "Grand Chief of the Mā" (= Grand Chief of the Meshvesh ), even worse: Behind the title there is the hieroglyphic symbol for 'Throwing stick', the determinative sign for a stranger.

Only in the fifth year of his reign was he officially mentioned as a pharaoh in Thebes and thus also in Upper Egypt. The main focuses of the government of Scheschonq I are the internal consolidation of Egypt, the campaign to Palestine and the construction activity, especially in Karnak . Sheschonq I strengthened his power by handing over the office of high priest to his second son Jupet, and the offices of 2nd, 3rd and 4th high priests were also filled with confidants. The elder son Namilt (I.) becomes governor in Herakleopolis . In the 5th year of Sheschonq I, the son of a subordinate prince of the Meshvesh restored order in the Dachla oasis after unrest and settled land and water disputes (Dachla stele ).

In a stele inscription Scheschonqs son Prince Iupet to a quarry opening in the second month of the season Schemu (925 v. Chr. In January) settled down to write to Scheschonqs 21st year of reign, Sheshonq will I also explicitly mentioned "Sjsq". The pronunciation "Schischeq / Schascheq" is derived from this. The materials from the quarry were intended for construction work in Thebes, which in turn is related to Sheschonq's successful Palestine campaign. The Egyptian chronology refers to the campaign in which Sheshonq is mentioned as Shishak in the Old Testament in connection with Rehoboam's fifth year of reign.

Scheschonq's Palestine campaign

Chronological evaluation

Sheschonq led the campaign according to Egyptian chronology in the spring or summer of 926 BC. About two years before his death. Herbert Donner's chronological setting of the reign of Rehoboam (926–910 BC) contradicts this. The “unsolved chronological problem” postulated by Donner is based on Old Testament dating approaches. In this regard, Egyptology uses Edwin R. Thiele (926 BC).

In the Egyptian chronology only the two so-called "anchor dates" of the ascension to the throne of Ramses II exist in the year 1279 BC. And Psammetich I in 664 BC The chronological approaches of the third intermediate period are still considered uncertain. The “chronology problem” mentioned by Donner also applies to the appointment of Sheschonq's reign, at least until new and reliable synchronisms with the Assyrian chronology are found.

Course of the campaign

The list of place names Scheschonq consists of three parts. In the first section the cities in Central Palestine are named in addition to the nine-arch peoples , whereby the places mentioned can be assigned to three regions. The second part includes numerous smaller towns in the Negev ; the third list focuses on the southern coastal area. The nature and extent of the first list section can Scheschonqs applications of Taanach up And Hapharaim and Mahanaim in Transjordan and from Gibeon to Aijalon recognize. Megiddo acted as a military base for the respective attacks.

| Jud-hamalek in hieroglyphics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Jud-hamalek Jwd-hmrk stele / monument of the king |

|||||||||

Old Testament research made attempts a long time ago to include the name of Jerusalem in the campaign, which was missing due to some illegible entries due to damage . In the first translations of the cities, Jean-François Champollion interpreted the 29th city sign as Joudahamalek and erroneously called this entry the Kingdom of Judah . The generally accepted translation was provided by W. Max Müller with "Jud-hamelek" ( hand of the king , in the figurative sense also monument of the king ), a city at that time in the coastal plain near Megiddo des Biblically around 1000 BC. Designated area of Israel .

After evaluating the archaeological results and the historical sources, the earlier assumptions regarding Jerusalem cannot be confirmed, especially since it was obviously not a political campaign. The southern Reich of Judah was also not the target of Scheschonq, as only peripheral areas were affected within a military action. In contrast, an extensive horizon of destruction can be seen in the northern locations of Pnuel , Tirza and Sukkot . Jeroboam's residence was in Pnuel . Possibly it was, among other things, a retaliatory strike by Scheschonq. However, the character of the campaign, which focused on trade routes and the associated localities, speaks against this. There is certain evidence that the places destroyed to the north were not an essential part of Scheschonq's campaign. Rather, it was one of numerous smaller military actions.

literature

- Kenneth Anderson Kitchen : The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt - 1100-650 BC . Reprint of the second edition with appendix from 1986 and the new introduction from 1996, Oxford 2015. ISBN 978-0-85668-298-8 .

- Karl Jansen-Winkeln : The Chronology of the Third Intermediate Period: Dyns 22-24. In: Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, David A. Warburton (eds.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology (= Handbook of Oriental studies. Section One. The Near and Middle East. Volume 83). Brill, Leiden / Boston 2006, ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5 , pp. 234-264 ( online ).

- Peter Jame, Peter G. van der Veen (Eds.): Solomon and Shishak: Current Perspectives from Archeology, Epigraphy, History and Chronology - Proceedings of the Third BICANE Colloquium held at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge March 26-27, 2011. (= BAR International Series. Volume 2732) Archaeopress, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-1-4073-1389-4 .

- Bill Manley: The 70 Great Secrets of Ancient Egypt. Frederking & Thaler, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-89405-625-8 .

- Susanne Martinssen-von Falck: The great pharaohs. From the New Kingdom to the Late Period. Marix, Wiesbaden 2018, ISBN 978-3-7374-1057-1 , pp. 178-184.

- Bernd Ulrich Schipper : Israel and Egypt in the royal era: The cultural contacts from Solomon to the fall of Jerusalem. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999, ISBN 3-525-53728-X .

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 249-250.

- Peter van der Veen: The name Shishak, an update. In: Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum. (JACF) Volume 10, 2005 , pp. 8, 42.

- Egyptian inscriptions. (= Texts from the environment of the Old Testament . Volume 1 / Old Series).

Web links

- Karl Jansen-Winkeln: Scheschonq / Schischak. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on May 26, 2012.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Document from the year 692 BC Chr.

- ↑ Annals of Ashurbanipal .

- ↑ a b c d e M. L. Bierbrier: Scheschonq IV . In: W. Helck; W. Westendorf: Lexicon of Egyptology, Volume V, Wiesbaden 1984, Sp. 585.

- ↑ a b c d K. A. Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt - 1100–650 BC, reprint of the second edition with appendix from 1986 and the new introduction from 1996, Oxford 2015, p. 288.

- ↑ For the translation and discussion of various interpretive approaches, cf. KA Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period, pp. 432-447.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Psusennes II. |

Pharaoh of Egypt 22nd Dynasty (beginning) |

Osorkon I. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sheschonq I. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Founder and 1st Pharaoh of the 22nd Dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 10th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 10th century BC Chr. |