Egyptian chronology

The Ancient Egypt

|

|

|---|---|

| Timeline | |

| Prehistory : | before 4000 BC Chr. |

| Predynastic time : |

approx. 4000-3032 BC BC 0. Dynasty |

| Early Dynastic Period : |

approx. 3032-2707 BC Chr. 1st-2nd Dynasty |

| Old Empire : |

approx. 2707-2216 BC Chr. 3rd to 6th Dynasty |

| First intermediate time : |

approx. 2216-2137 BC Chr. 7th to 11th Dynasty |

| Middle Kingdom : |

approx. 2137–1781 BC Chr. 11 to 12th Dynasty |

| Second split time : |

approx. 1648–1550 BC BC 13th to 17th Dynasty |

| New Kingdom : |

approx. 1550-1070 BC Chr. 18 to 20 Dynasty |

| Third intermediate time : |

approx. 1070–664 BC BC 21st to 25th Dynasty |

| Late period : |

approx. 664-332 BC Chr. 26 to 31 Dynasty |

| Greco-Roman time : | 332 BC Chr. To 395 AD |

| Data based on Stan Hendrickx and Jürgen von Beckerath | |

| Summary | |

| History of Ancient Egypt | |

| Further information | |

| Portal Egyptology | |

The Egyptian chronology deals with the chronological classification of historical dates , events and developments of the material culture of ancient Egypt . The chronology differs clearly from the cultural history , which directs a certain, cultural-historical perspective on the objects. The focus is therefore on gaining a higher-level temporal framework for a reconstruction of history. In addition, as a fundamentally independent branch of science within the chronology, “the theory of how people deal with time” has emerged. Thomas Schneider, for example, states that it is not possible to determine the exact time of the sources for the chronology and thus “the yield of Egyptological sources for understanding how the Egyptians dealt with time is greater than for an absolutely modern positioning of the Egyptians at this time ".

Differentiation between absolute and relative chronology

A basic distinction is made between relative chronology and absolute chronology . The relative chronology deals with the temporal sequence and duration of historical processes, governments or archaeological artifacts and layers of finds ( stratigraphy ). It answers the question of whether an object is older or younger than another, or whether an event occurred before or after another. Accordingly, a distinction is made between historical chronology and archaeological chronology within the relative chronology .

The ancient Egyptians mainly dated to the years of reign of the respective ruling kings and also kept king lists, which are more or less complete for us. There are also historical works by ancient historians. In particular the historical work of Manetho , which is known under the Latin title Aegyptiaca , is (despite all falsifications) an important source for the historical-relative chronology. From this a (relative) basic structure can be constructed with the succession of kings and the definition of their government lengths (see list of pharaohs ).

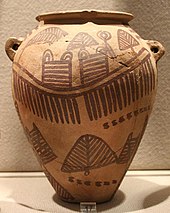

The archaeological-relative chronology deals with the internal order of sources as a methodological instrument. This includes in particular the ceramic seriation , but also the typological sequence of scarabs or the stratigraphy of archaeological layer sequences and, in general, the seriation of various artifacts . The method of seriation was invented by Flinders Petrie in 1899 . He introduced them to the Naqada culture in order to make a relative sequence of ceramics on the basis of decorative characteristics and shapes. By studying ceramics, other artifacts, environmental factors and agricultural changes, the basis for a holistic view of Egyptian history can be created, in which political developments are seen in the context of a long process of cultural change. However, there is still no comprehensive classification based on the development of material culture in dynastic Egypt.

The absolute chronology tries to transfer the events to our era, that is, to provide them with concrete dates. For this play astronomical and scientific methods an important role. The Sothis dating tried to determine the early rise ( heliacal rise ) of the Sothis in absolute terms . The early rise of the star Sirius (Greek Sothis) was at times understood as an announcement of the imminent flooding of the Nile and thus set the New Year in relatively good agreement with the tropical year (solar year). However, the point in time of this rise moves through the solar year over a period of time that was already calculated at 1460 years. In addition, the Egyptians introduced an "administrative calendar" which, with exactly 365 calendar days without a leap day, had the disadvantage that it was shifted by one day every four years from the tropical year. Since the Egyptian calendar dates can be converted into Julian (and Gregorian ), it is theoretically possible to determine in which year the Sothis Rise fell on a traditional date. However, certain uncertainty factors must be taken into account. Until the 1990s, the Sothis date from al-Lahun on the Berlin 10012 papyrus formed an important pillar for the absolute chronology of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom . Jürgen von Beckerath, for example, still believed in 1997 that this date could be precisely defined in relation to our time calculation and that it would be able to obtain secure data from it. The situation has changed a lot since then. With increasing refinement of the 14 C method , a match with the astronomical data became difficult to establish, and there were insurmountable difficulties with the synchronization with absolute data from other cultures. This is why 14 C dating (radiocarbon dating) is also increasingly used for ancient Egypt , a method for radiometric dating of carbon-containing , especially organic materials. But this method also offers a certain space for uncertainty. Since 2000, researchers such as Georges Bonani and Bronk Ramsey have tried to develop a new chronology of Egypt based on 14 C dates and statistical methods.

Historical-relative chronology

annals

The Egyptians kept lists in the archives of the residence and probably also in the larger temples, on which they recorded the names of the pharaohs since the beginning of the first dynasty with their lengths of reign. These annals recorded on papyrus rolls have been lost, but certain remains of copies have been preserved.

Annal stone of the 5th dynasty

The remains of a copy of such annals have been preserved, especially from the earliest times. This 5th Dynasty annal stone probably came from Memphis, the capital of the Old Kingdom. The two largest fragments are called " Palermostein " ( P ) and " Kairostein " ( C1 / K1 ) due to their current location . In addition, according to Wolfgang Helck, five smaller parts are listed under the names P1 and “Cairo Fragments” No. 2 to 5 ( C2 – C5 / K2 – K5 ).

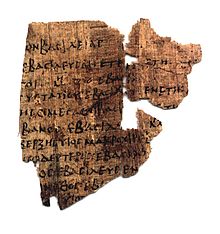

The Turin Royal Papyrus

There are also fragments of a somewhat negligent copy of a royal list from the archives, which an official or priest in the time of Ramses II wrote on the back of a list of duties, the so-called Turin royal papyrus. Certain errors have surely crept in due to the constant updating and repeated copying of the king lists. The papyrus was found in Luxor around 1820 , brought to Europe by Bernardino Drovetti and acquired by the Egyptian Museum in Turin in 1824 . On the transport to Turin it had disintegrated into innumerable small pieces.

Already Jean-François Champollion , the first decipherer of hieroglyphics , realized that they were a royal list. Gustav Seyffarth was the first to try, albeit without knowledge of the hieratic script , to arrange the fragments using the papyrus fibers, the form of writing and the color. Since then, small suggestions for improvements in the arrangement of the fragments have been made repeatedly.

Had the papyrus been preserved in its entirety, it would contain the chronological order of all kings from the 1st to the 17th dynasty, with fairly reliable information on the length of their reigns. For Jürgen von Beckerath it can be seen from the remains "that the Egyptians had a tradition based on correct, not mythical-fantastic numbers back to the earliest times of their history - in contrast to the other peoples of antiquity." this tradition with the rule of gods and with dynasties of "spirits", but this only applies to the period before the first dynasty, about which there was no longer any written record.

Royal pedigrees

The royal lists in the archives also served as a template for royal pedigree charts that were attached to the walls of temples in the New Kingdom. The purpose of this list was to allow the ruling king's predecessors to participate in his sacrifices. If possible, all legitimate rulers since King Menes were listed, as they formed a direct line of ancestors according to the royal dogma.

There are four royal pedigrees in total:

- The oldest is the Karnak King List from the time of Thutmose III. On it the pharaoh stands sacrificing in front of a total of 61 seated kings. This representation only gives an apparently arbitrary and not chronologically ordered selection of rulers. It only has some significance because it also has recognized rulers of the 1st and 2nd intermediate periods in Thebes who are missing in other lists.

- The list of kings in the temple of Seti I in Abydos is very well preserved . She names 76 kings, starting with Menes . Only the rulers of the interim times and some rulers who were later regarded as illegitimate are missing.

- Also in Abydos is the destroyed list of Ramses II. Parts of it are now in the British Museum. It is basically a copy of the List of Set.

- Another list of kings was discovered in the grave of the Memphite priest Tjuneroy in Saqqara . It is probably a copy of an annals tablet that must have been in the Ptah Temple in Memphis. Starting with Ramses II, it ends backwards in the middle of the 1st dynasty . For reasons of space, the first kings are missing.

Ancient historians and scholars

The history of Manetho

An important source for the chronology is, despite all falsifications, the historical work of Manetho , which is known under the Latin title Aegyptiaca . Manetho was probably a priest from Sebennytos in Lower Egypt , who was probably under the pharaohs Ptolemy I , Ptolemy II and Ptolemy III. lived. Georgios Synkellos set Manethos work at the same time or a little later than Berossus in the reign of Ptolemy II (285–246 BC), under which he is said to have written the Egyptian Empire . Manetho's motives may be based on the one hand in the Ptolemaic ignorance of the ancient Egyptian language and on the other hand in the refutation of Herodotus accounts of ancient Egyptian history .

The key dates that form the basic structure of Egyptian chronology come from writings that were written between the 1st and 4th centuries AD and quote the Egyptian priest Manetho . These are:

- Flavius Josephus ( Antiquitates Judaicae [The Jewish Antiquities] and Contra Apionem ),

- Sextus Iulius Africanus ( Chronologies ) and

- Eusebius of Caesarea ( Chronicon ).

The latter two authors again served as a template for the world history of George the Monk (Syncellus) .

Due to the often written, altered and mutilated fragments that testify to the original work of Manetho, conclusions for the dating of Egyptian history can only be drawn with great caution. Some of the royal names have changed so much (e.g. in the 15th Dynasty) that they are difficult to assign. Nevertheless, the work can be used to supplement the existing lists, especially for the period after the New Kingdom, for which there are no ancient Egyptian lists.

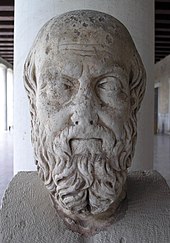

Greek historian

Hecataus of Miletus (560–490 BC) and Herodotus of Halicarnassus (approx. 484–425 BC ) are at the beginning of the still handed down history . As well-traveled men, they describe the countries and peoples of the world they know. Herodotus traveled to Egypt at the time of the Persian rule around 450 BC. And describes his impressions about it in the second book of his histories . First he describes the topography, customs and traditions and then a description of the history of the country. When describing the 26th Dynasty , which was not so long ago , he is relatively precise, but Herodotus did not really depend on an exact chronological order of the rulers, rather it was about telling interesting incidents that he took from popular popular literature. For example, he pushes the builders of the pyramids of Giza (Cheops, Chephren and Mykerinos) between Ramses III. and the late period. Even so, the later Greek authors relied mainly on Herodotus' account of history and ignored the more reliable work of Manethus.

Even before the conquest of Egypt by the Persians in 525 BC Hekataios had obviously visited Egypt, but his work has been lost except for fragments.

Eratosthenes is considered to be the first chronograph and founder of scientific chronography . On behalf of the Egyptian kings from the Ptolemy dynasty, he directed the library of Alexandria , the most important library of antiquity, for around half a century . His interest, however, was apparently directed more towards the gathering of culturally and historically interesting news than the determination of an absolute chronology. Therefore, its role in this area is not as prominent as it was often assumed in older research. Among other things, he is said to have translated a list of the Egyptian rulers of Thebes from Egyptian into Greek on a royal commission. Such a list has been preserved, but cannot come from him in the present version. To what extent it contains material that can be traced back to him is unclear.

The Almagest of Claudius Ptolemy

Almagest is one of the main works of ancient astronomy that goes back to the Hellenistic-Greek scholar Claudius Ptolemy . This textbook, which he created around the middle of the 2nd century with the original title Mathematike Syntaxis (Eng. "Mathematical Compilation"), comprised the most competent representation of the astronomical system of the Greeks. Later copies of the highly respected work were titled Megiste Syntaxis ("Greatest Compilation"), which was adopted as al-madschisti in the Arabic translations and from there passed into today's usage as Almagest . In contrast to other works of that time, the text of the Almagest has survived in its entirety.

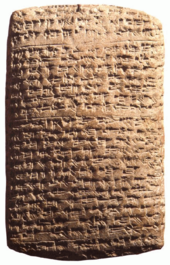

For the dating of the recorded celestial phenomena, Claudius Ptolemy created a canon of the ruling years of the late Egyptian period, which was used to determine the time between the 27th and 31st centuries. Egyptian dynasty matters. For the time before Alexander the Great , Ptolemy used the records of the Babylonian priests, then those of the Alexandrian scholars. Ptolemy converted the chronological information regarding astronomical records to the Egyptian change-year calendar . In order to avoid ambiguity, he names the beginning and ending ancient Egyptian day for nocturnal events . Due to the precise information, the respective occurrences in the Julian calendar can be precisely dated.

In addition to its importance for the Egyptian chronology, the canon of Ptolemy is also valuable for the chronology of Babylonia and Assyria, since it determines the governments of the last rulers of the two countries and thus the connection of their lists of kings to the absolutely dated Hellenistic period.

Absolute chronology

Astronomical dating

Sothis dating

As the embodiment of the star Sirius , the goddess Sothis announced the imminent flooding of the Nile in ancient Egypt with her early rise ( heliacal rise). This event was an important signal generator for agriculture, because with the Nile flood the irrigation and supply of the Nile mud, which is important for cultivation and sowing, began. The New Year festival ( Sothis festival ) was also associated with this . In addition to this natural calendar, the Egyptians also introduced an administrative calendar, which , as a changing year calendar, had the disadvantage that it had no leap day and thus deviated from the solar year by one day every four years. The calendar thus “wandered” through the seasons. The duration of the period after which the changing year calendar again coincides with the actual seasons can be calculated through the respective temporal deviation of the change year from the solar year. In relation to Ancient Egypt, it is the Sothis cycle , the period of time that Sirius needs with his heliacal rise to go through the Egyptian 365-day calendar.

Since the Egyptian calendar dates can be converted into Julian dates, it is theoretically possible to determine in which year the Sothis Rise fell on a traditional date. However, one cannot determine the data of the Sothis rising simply by back-calculating, but must consider factors such as the precession of the earth's axis and the proper movement of Sirius. So you have to use astronomical calculations; otherwise one receives dates on which the Sothis rise could not be seen at all.

In addition, you have to take into account various factors that lead to a certain uncertainty in the calculated data:

- The arc of vision of Sirius : In order for the star Sirius to be visible on the horizon during its heliacal rise, the distance to the sun still below the horizon must be large enough so that it is not outshone by the sun's scattered light. This minimum distance for the visibility of the star in the heliacal rising between the star and the sun is called the arc of vision . The size of the visual arc depends on certain variable factors, such as atmospheric conditions (e.g. increasing light and air pollution). The astronomer Bradley Schaefer calculated with full use of modern astronomy a visual arc of about 11 °, but still gives a possible deviation of +/- 20 years for the Sothis cycle.

- Observation site: The calculation result depends on the geographical latitude of the observation site. Knowledge of the observation location is particularly important for Egypt, as it extends from north to south over more than seven degrees of latitude, because every deviation by one degree of latitude changes the result four years earlier or later.

- Tetraëteris: Since the heliacal rise of the Sothis is shifted by one day every four years compared to the administrative calendar, it falls on the same day in the administrative calendar for four years. This means that four consecutive years (Tetraëteris) are possible for dating from the outset.

The most important Sothis date for the absolute dating of the Middle Kingdom comes from Papyrus Berlin 10012 from al-Lahun . The papyrus consists of the two fragments 10012A VS and 10012B , which were acquired by Ludwig Borchardt in al-Lahun in 1899 and then published for the first time. In the meantime, the papyrus could be given to King Sesostris III. assign. The papyrus provides the oldest and most valuable Sothis date. The text passage reads: Know that the coming out of Sothis will happen on August 16 th. May you [notify] the priests of the hours of the temple of the place Sechem-Senwosret (Lahun), of Anubis on his mountain and of Suchos. The other fragment provides the year 7 of an unnamed king, in which generally Sesostris III. is assumed, but theoretically it is also Amenemhet III. could act. The location of the observation is largely based on the height of Memphis , which deviates only slightly from Lahun. Rolf Krauss and Erik Hornung, on the other hand, started with Elephantine , assuming that this place was the zero point of Egypt (similar to today's Greenwich ). This assumption led to a lowering of the chronological approaches, since the early rise in Elephantine can be observed six days earlier than in Memphis and accordingly the calculated date is 24 years later than in Memphis. The choice of Elephantine was not made on the basis of textual information, but arose as a consequence of the need to "reconcile the Sothis date with a deep chronology."

Until the 1990s, the Sothis date from al-Lahun formed an important pillar for the absolute chronology of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom. Jürgen von Beckerath, for example, still believed in 1997 that this date could be precisely defined in relation to our time calculation and that it would be able to obtain secure data from it. In contrast, other methods, such as C14 dating, were of little value. The situation has changed a lot since then. With the increasing refinement of the C14 method, a correlation with the astronomical data became difficult to establish, and there were insurmountable difficulties with the synchronization with absolute data from other cultures. Accordingly, the value of astronomical data has been questioned more and more. Within the method of Sothis dating, Egyptologists were faced with insurmountable astronomical difficulties, particularly with regard to determining the sighting conditions for the event. In addition, there was no consensus on establishing a reference point for observing astronomical phenomena.

Rolf Krauss gave up Sothis dating as the primary dating method and only sees a certain relevance for it in connection with moon dating. Thomas Schneider also agreed with this judgment: “The Sothis date from Illahun is no longer an absolute fixed point for the chronology of the Middle Kingdom and can at most in the sense of a rough positioning - with Illahun as a point of reference, approx . - be used."

Lunar dating

The Egyptians kept a lunar calendar to establish religious festivals . In contrast to the solar year or the civil year, the sum of the twelve lunar months is only 354 days. A few double dates have survived, especially from al-Lahun, in addition to the indication of the heliacal rise of Sirius, entries of fixed dates in connection with lunar month entries from temple diaries have been preserved. In contrast to the other ancient oriental countries , the lunar month did not begin a short time after the new moon with the new light , but with the first day of not seeing the moon at dawn . The second day of the new month was the one with the first visibility of the crescent moon. This already gives rise to certain uncertainties: observations of the old moon and new moon are inaccurate. It is not clear whether the Egyptians used a schematic calendar for forecasting and whether there were certain restrictions in the observation (e.g. haze, clouds or visual impairment).

The same moon phase is repeated after 25 Egyptian years (= 309 lunar months). Each century therefore offers several hits for a specific lunar date. A suitable lunar date is therefore statistically less relevant than a Sothis date. This fact of the repetition of the phases of the moon prompted research to a large extent to use moon data only in addition to the Sothis data.

In 1985, Rolf Krauss calculated the correspondence of the lunar dates for three intervals specified by him for the Sothis date. The approach 1818/17 BC According to his calculations, BC gave the best agreement. He subjected the results to a statistical significance test and considerations about the cyclicity of the moon phases. In order to get a better match, he then corrected those dates for which there were at least one day of incorrect moon data: "After the correction, 18 out of 20 dates are correct for the calculation." With this he sees a low chronology and Elephantine as a reference point for the Sothis -Date proven on.

In a first step, Ulrich Luft published all relevant sources from al-Lahun. Next, he determined the distance from all lunar festivals to the 1st lunar month day (new moon), so that all fixed dates can be related to the new moon. In his data catalog, he also differentiates between the significance of the individual data. He rates four dates as “basic”, 15 as “certain”, 14 as “likely” and nine as “still usable”. In the higher chronology (year 7 = -1865), air receives 25 matches of observation and calculation and 14 deviations by one day, while the lower chronology with Elephantine as the reference location provides only 5 hits, the correct lunar date, however, 24 times by one and Is missed 10 times by two days.

LE Rose subjected the approaches of Krauss and Luft to a critical evaluation and found numerous calculation errors. So he came to a negative judgment on both approaches. Even so, Luft's results stood up to scrutiny better than those of Krauss.

In order to avoid the difficulties that arose from the more recent discussions about the Sothis date from al-Lahun, Rolf Krauss tried in a new approach to establish an Egyptian chronology based on the lunar dates without reference to the traditional Sirius dates . In doing so, he gave up the Sothis date as a support for absolute chronology. He replaced the earlier significance test with a calculation of the probability of the lunar data. However, this approach was also heavily criticized. For example, his hit rate is only possible through the corrections he has made to the data. Schneider, on the other hand, comes to the conclusion that the approach is incorrect with a probability of 9: 1. Accordingly, the lunar data can only be used in the sense of a rough limitation.

The C14 method

The 14 C-dating ( radiocarbon dating ) is a method for radiometric dating of carbon-containing , in particular organic materials. The process is based on the fact that the amount of bound radioactive 14 C atoms in dead organisms decreases in accordance with the law of decay . With increasing refinement, the method is also used for determining time in Egyptian chronology. Nevertheless, this method also offers a certain amount of room for uncertainty. In order to achieve usable results, a good selection of samples (as short-lived samples as possible from a reliable and well-defined archaeological context), the correct pre-treatment (avoidance of contamination ) and careful and precise measurement in the laboratory are required.

As with any physical measurement, the measurement error is divided into a statistical error and a systematic error. In the case of the counter tube method, for example, the statistical nature of the radioactive decay contributes to the statistical error. The simple standard error of the measured value, which is calculated from the standard deviation , is usually given as a measure of the measurement accuracy . Roughly speaking, this means that if the same sample is measured very often, about two out of three results will be within this range, the confidence interval , and one will be outside. By definition, a 68% probability is given for which the sample lies within the measured interval in the normal distribution . In addition, an interval is given with a 95 percent probability in which the sample lies. However, this has a range that is twice as high as the date searched for (e.g. a range of 60 years instead of 30 years with a 68 percent standard deviation).

This error, which is given by the laboratory in the easily readable form ± n years, actually only describes the uncertainty in the determination of the isotope ratio. Additional sources of error must be taken into account for the uncertainty in determining the age. In particular, these are:

- All falsifications during the cleaning and preparation of the sample (rather negligible)

- All falsifications from the creation of the sample to the discovery today: The 14 C method measures the time of death of an organism, which is not necessarily the time at which an archaeological layer was deposited. So if an old beam was reused in a prehistoric house, the dating of that beam will correctly date the beam itself, but not the start of construction on the house.

- All deviations in the carbon age of the sample from the age of the layer to be determined.

- All purely statistical fluctuations between apparently identical samples from the same find context.

- All deviations of the 14 C concentration of the sample material from the ambient air during the lifetime.

The 14 C data tend to provide results for the Early Dynastic Period and the Old Kingdom that are older than the historical-archaeological age data:

“For the period between (conventionally) 3000 and 2250 BC The 14 C dating provides ages that are several centuries above the historical archaeological ages. The same trend, however, with smaller discrepancies of 100 to a maximum of 150 years, occurs for the period between (conventionally) 1600 and 1400 BC. For the time around (conventionally) 1200 BC. BC no discrepancy seems to be detectable, although some measurements point in the direction of higher and others in the direction of lower 14C ages. For the subsequent period and especially for the period around (conventionally) 1000 to 900 BC BC indicate 14C ages, which could be 60 to 100 years lower than the historical-archaeological age. However, it is difficult to make definitive statements due to the comparatively high margin of error. "

As a consequence, natural scientists are calling for the conventional chronology of the early periods to be corrected to higher values. In doing so, they point to methodological uncertainties in the historical-archaeological dating, although the error can potentially also be on the part of the 14 C dating. So far, most archaeologists have been reluctant to replace the historical-archaeological data in favor of the 14 C data.

So far, researchers have tried to develop a new chronology of Egypt based on 211 14 C dates. The samples were short-lived materials from baskets, textiles, plants, grains and fruits from the holdings of European and American museums, which could be clearly assigned to the year of the reign of a pharaoh or the year of the foundation of a temple. They also used a statistical method to identify patterns in the radiocarbon and historical data to find the most likely relationships between the two. Bronk Ramsey and others developed three separate, multi-phase models for each of the main epochs ( Old Kingdom , Middle Kingdom, and New Kingdom ) to get a precise C14 chronology. The modeled C14 results have an average calendar accuracy of 76 years for the Old Kingdom and agree well with the historical chronology of Ian Shaw. The results for the Middle Kingdom have an average calendar accuracy of 53 years. The results for the New Kingdom, based on 128 C14 dates with an average accuracy of 24 years, do not support the more recent (low) historical chronology, but agree well with the chronology used by the New Kingdom around 1550 BC. Begins. The model prefers a somewhat older beginning of the New Kingdom around 1560 BC. Chr.

Using the radiocarbon method, newly determined data now lead researchers to the view that the chronology of the predynastic up to and including the 1st dynasty of the early dynastic period should be specified and corrected with regard to the timeline.

Synchronisms

Synchronisms are historically documented connections to simultaneous data from other cultures. Where the Egyptian sources are insufficient because of their gaps and there are synchronisms with more reliably datable events, they can offer chronological support.

Ancient Greece

For the Egyptian chronology usable dates from ancient Greece only exist from a relatively later period, before that the Egyptian dates are more certain and serve more as a support for the chronology in the Aegean area. For the later period of the 27th to 31st dynasty, Greek writers provide usable dates for ancient Egypt:

- Herodotus reports in his histories that four years after the Battle of Marathon , the 490 BC. Took place, a revolt against the Persian rule in Egypt (27th Dynasty) has given.

- The reign of Inaros II put the Greek historians during the Persian rule to about 460 BC. Chr. Thus Inaros was the son of Psammetichus IV. And anti-king of Artaxerxes I . He encountered 463/2 BC. From the fortress Marea into the Nile Delta and defeated the satrap Achaimenes near Papremis . 460 BC He brought the Egyptians to a revolt against the Persians and ruled, apart from Memphis , all of Lower Egypt . As a support he won 459 BC. The Athenians . The uprising only collapsed in the spring of 454. It should have broken out shortly after the murder of Xerxes I (Aug. 465).

- Euagoras I , a king of the ancient city-state of Salamis on Cyprus , waged a ten-year war with the Persian Empire (from 390 to 380 BC). He entered into an alliance with Athens and Nepherites I of Egypt . His successor Hakor continued this alliance.

- In 383 Hakor was able to repel an advance by the Persians.

- In 373, Nectanebo I was also able to repel a Persian attack.

- One year after the satrap revolts against Artaxerxes II in 360 BC In his 46th year of reign , the Egyptian pharaoh Tachos undertook a campaign to Asia himself.

- The reconquest of Egypt by Artaxerxes III. , with which the 30th dynasty ends, can be set to winter 343/42.

- After Alexander the Great Tire in August 332 BC. He marched into Egypt about three months later, but surely after November 14th, the Egyptian New Year's Day. The city of Alexandria was founded in 331.

Assyrian Empire

The Assyrian Empire existed for about 1000 years, from the 18th century BC. Until its annihilation around 609 BC. The Assyrian King List (AKL) lists the names of the Assyrian kings from the beginning to 722. Between 722 and 911, the AKL can be compared with the eponym list, which is completely available between 649 and 911. For the older time there are few points of contact with Egypt, only at the end of the 8th and 7th centuries there were direct connections and there was even a temporary occupation of Egypt by the Assyrians. Assyrian-Babylonian synchronisms also determine the Babylonian chronology, which in turn shows important synchronisms with Egypt and the outcome of which can be determined in time using the Almagest of Claudius Ptolemy.

- For the older Assyrian kings it is only documented (in the Amarna letters numbers 15 and 16) that Aššur-uballit I wrote to Pharaoh Akhenaten soon after his accession to the throne . The correspondence of Aššur-nadin-ahhe II. With Amenophis III. mentioned.

- In the annals of Šarrum-ken II from 712 it is reported that Egypt now belongs to Nubia: With this it is certain that the conquest of Lower Egypt by the Nubian (Cushitic) pharaoh Shabako , the end of the Bokchoris (24th dynasty) and the beginning the 25th Dynasty, in the year 712 or shortly before.

- In February 673 BC Chr. Took Asarhaddon a first attack on Egypt, that of Taharqa was repulsed.

- In 671 BC Asarhaddon first besieged Tire , whose king Baal defected to Taharqa, and then leads on 16./29. June and July 1, three victorious open field battles against the Egyptian army. After the third battle, Memphis is captured on July 5th.

- After Asarhaddon withdrew, Taharqa regained power. Azarhaddon drew in 669 BC. Again against Egypt, but died on the way. 667/666 BC The successor of Asarhaddon Ashurbanipal defeats the Egyptian army and subdues Egypt as far as Thebes.

Archaeological-relative chronology

The archaeological-relative chronology deals with the internal order of sources as a methodological instrument. This includes in particular the ceramic seriation, but also the typological sequence of scarabs or the stratigraphy of archaeological layer sequences and, in general, the seriation of various artifacts .

The method of seriation was invented by Flinders Petrie in 1899. In the late 20th century there was a tremendous increase in the study of Egyptian ceramics, both in terms of the amount of sherds that are analyzed (from a variety of different archaeological sites) and in the range of scientific techniques that have been used since then, to gain more information from ceramics. So one began to classify the changes in the vessel types more and more precisely over time. For example, the shape of bread baking molds was subject to major changes at the end of the Old Kingdom. However, it is not yet entirely clear whether these processes have social, economic and technological causes or whether they are just a “fad”. Seen in this light, there have been many reasons for the changes in material culture and only some can be linked to the political changes that dominate conventional views of Egyptian history.

Nevertheless, connections can be made, for example, between the political and cultural change and centralized production of ceramics in the Old Kingdom and the resurgence of local types of pottery during the politically decentralized First Intermediate Period, and a renewed unification during the reunified 12th Dynasty. By studying ceramics, other artifacts, environmental factors and agricultural changes, the basis for a holistic view of Egyptian history can be created, in which political developments are seen in the context of a long process of cultural change.

Ceramic dating using the example of the Naqada culture

Petries "Sequence Dating"

WM Flinders Petrie was the first to attempt a ceramic seriation (his so-called “sequence dating”) using ceramics from the Naqada culture . He published the first study on the relative chronology of the Naqada culture in 1899. His first "predynastic" corpus is based on the grave goods from the cemeteries of Naqada , Ballas and Diospolis Parva . Originally he distinguished between nine classes and over 700 types of ceramics. For the classification he selected 900 intact graves of five or more types from the more than 4000 excavated graves. To do this, he created index cards and tried to organize them. He made two main observations:

- “White Cross-lined” ceramics on the one hand and “Decorated” and “Wavy Handled” ceramics

- The development of the shape of the "Wavy-Handled" types ranges from spherical to cylindrical and from functional handles to decorative lines

After Petrie had sorted all the index cards, he divided them into 50 groups, each of which contained 18 graves. He defined SD 30 as a starting point in order to leave room for possible earlier cultures that had not yet been discovered. He further subdivided the 50 “Sequence Dates” into three groups, which he classified as archaeologically, culturally and chronologically different and named them after important sites: Amratian (SD 30-37), Gerzean (SD 38-60) and Semainean (SD 60 -75).

Petrie created a second corpus for the “protodynastic” ceramics based primarily on the finds in the Tarchan cemetery . Here he distinguished 885 types, but no classes, which makes it difficult to use. This partially overlaps with the “predynastic” body. It starts with SD 76 and goes up to SD 86, whereby SD 83-86 remain fairly theoretical due to the lack of material from the 2nd dynasty. This time the transition to the new “Sequence Dates” was mainly based on typological breaks, which Petrie defined based on the development of the Wavy-Handled types. He also linked the "Sequence Dates" with the historically dated ceramic types and other objects in the royal tombs of the early dynasties in Abydos.

Some methodological problems arose in Petrie's classification:

- There is no distinction between typology and chronology.

- The classes are very heterogeneously defined.

- The definitions are not bound by strict rules.

- Only graves with five or more objects were used, which means that the early periods are underrepresented.

- Regional differences were not taken into account.

- The horizontal distribution of the ceramics within a cemetery was not considered as a further criterion.

- A systematic problem with “Sequence Dates” is that when new graves are added, new types have to be defined.

- Typology of Wavy Handled ceramics according to Petrie

Emperor's step chronology

The first to re-examine the relative chronology of the predynastic period was Werner Kaiser . He largely accepted Petrie's typology. The cemetery 1400–1500 in Armant served as a starting point for Kaiser . In addition, Kaiser also used the horizontal distribution of the pottery and if a period in Armant was not documented, the pottery from other cemeteries as well. He distinguished three spatial zones within the cemetery according to their relative frequency, each of which was dominated by a specific group: Black-Topped, Rough Wares and Late and Wavy Handled Wares. Within these periods he made subdivisions which he called stages. In total, he identified eleven stages. These do not entirely, but largely agree, with Petrie's classification.

According to Kaiser, the following main levels result:

- Level I: This level covers all sites in Upper Egypt, from the Badarian regions to south of Aswan . The cemeteries are dominated by the "Black Topped" pottery, which makes up more than 50% of the pottery. The second most important types are "Red-Polished" and "White Cross Linded" ceramics.

- Stage II: According to Werner Kaiser’s definition, this stage should be dominated by the “rough” ceramic. However, in level IIa, the "Black Topped" still dominated over the "Rough" ceramic. With the transition from level IIb to IIc, "Wavy Handled" ceramics were introduced. In addition, some new "Decorated" types were added.

- Stage III: In this stage, the "late" ceramic is numerically predominant over the "rough". It should be noted, however, that a large number of the late types were produced in the manner of the rough goods. This stage is particularly important for the relative chronology of the predynastic time and the early period, as it contains the final phase of state formation and can be partially linked to the historical chronology of the 1st and 2nd dynasties.

There were also some problems with this chronology:

- Almost only one cemetery was used, which makes regional differentiation impossible.

- Levels Ia, Ib and IIIb are rather hypothetical, especially the development of the Wavy-Handled class.

- Kaiser only published an abridged version as an article in which only the characteristic types for each level are shown.

Stan Hendrickx

Since the mid-1980s, Stan Hendrickx continued and improved Werner Kaiser's model. He proceeds according to the same principle by differentiating groups of graves that belong together (i.e. taking into account the spatial distribution within a cemetery) and not only differentiating the graves on the basis of their content. This results in a conflict of interest between the search for a narrower chronological arrangement for all ceramic types on the one hand and the definition of spatially well-defined groups on the other. Neither of these two criteria can be accepted as predominating over the other.

Computer seriation

BJ Kemp made a multi-dimensional scaling of the graves in cemetery B in el-Amrah and in the cemetery of el-Mahasna. This seriation was not used to evaluate Kaiser's step chronology, but only Petries “Sequence Dating”.

TAH Wilkinson carried out a seriation of 8 pre- and early dynastic cemeteries on the basis of 1420 (out of a total of 1542) types from Petrie's corpus, which were combined into 141 groups. There were big problems with the newly defined groups, as they are very heterogeneous. For example, the cylindrical vessels with and without incised decorations were put in the same group, which according to Kaiser was an important chronological indicator.

Dating in Wikipedia

The first attempt at an Egyptian chronology in the early modern period was probably made by Joseph Scaliger around 1600, who used the information provided by the chronicler Eusebius and the Ptolemaic canon ( Thesaurus Temporum and Emendatio Temporum ).

The earliest attempts at a chronology come from the 20th century in 1904 and 1907 by Eduard Meyer , who in turn is based on Flinders Petrie ; a later one by R. Weill from 1928 and the last comprehensive chronology by Ludwig Borchardt from 1935.

It was not until 1997 that the Egyptologist Jürgen von Beckerath revised this chronology with the MÄS 46 ( Münchner Ägyptologische Studien , Volume 46), which today is the standard work in international specialist circles. In individual epochs there are of course different data due to recent research or other interpretations of the scientific evidence. A guaranteed, solid framework does not exist due to advancing knowledge, but the chronology is further narrowed down by more recent studies.

In the articles of the German-language Wikipedia, von Beckeraths use dates, unless otherwise stated. They have largely established themselves in the more recent scientific literature. If there is no dating of the aforementioned author, information from Thomas Schneider is used.

literature

General overview

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Chronology of the pharaonic Egypt. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 .

- Wolfgang Helck : weak points in the chronology discussion. In: Göttinger Miszellen No. 67 , 1983, pp. 43-49.

- Erik Hornung , Rolf Krauss , David A. Warburton (eds.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology (= Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1: The Near and Middle East. Vol. 83). Brill, Leiden / Boston 2006, ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5 .

- Kenneth Anderson Kitchen : The Chronology of Ancient Egypt. In: World Archeology. Volume 23, No. 2, 1991, pp. 201-208; phys.msu.ru (PDF; 965 kB).

- Thomas Schneider: The end of the short chronology: A critical balance sheet of the debate on the absolute dating of the Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period. In: Egypt and Levant. No. 18, 2008, pp. 275-313.

- Thomas Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs . Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-7608-1102-7 .

- Thomas Schneider: A special kind of puzzle . In: Spectrum of Science - Archeology, History, Culture . Special 1.17. Holtzbrinck, 2017, ISSN 0170-2971 , p. 38–43 ( partial view [accessed May 2, 2017]).

- Ian Shaw (Ed.): Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2000, ISBN 0-19-815034-2 .

- Hana Vymazalová , Miroslav Bárta (Ed.): Chronology and archeology in ancient Egypt: (the third millennium BC). Czech Institute of Egyptology - Faculty of Arts - Charles University, Prague 2008, ISBN 978-80-7308-245-1 .

- William A. Ward : dating, pharaonic. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 229-32.

Annals and Ancient Historians

- Georges Daressy : La Pierre de Palerme et la chronologie de l'ancien empire. In: Le Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale. (BIFAO) 12, 1916, pp. 161-214.

- Alan H. Gardiner : The Royal Canon of Turin. University Press, Oxford 1959 (Reprinted. Griffith Institute, Warminster 1987, ISBN 0-900416-48-3 ).

- Wolfgang Helck : Investigations into Manetho and the Egyptian King Lists (= Investigations into the history and antiquity of Egypt. Vol. 18 ). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1956.

- Jaromir Malek: The Original Version of the Royal Canon of Turin. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology. 68, 1982, pp. 93-106.

- Donald B. Redford : Pharaonic King-Lists, Annals and Day-Books. A Contribution to the Study of the Egyptian Sense of History (= Publications Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities Publications. [SSEA] Volume 4). Benben Publications, Mississauga 1986, ISBN 978-0-920168-08-0 .

- Heinrich Schäfer : A fragment of ancient Egyptian annals (= treatises of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences. Appendix: treatises not belonging to the academy of scholars. Philosophical and historical treatises. 1902, 1, ZDB -ID 221471-4 ). Publishing house of the Royal Academy of Sciences, Berlin 1902, online .

- William Gillian Waddell: Manetho (= The Loeb classical Library. Vol. 350 ). Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.) 2004 (Reprint), ISBN 0-674-99385-3 .

- Toby AH Wilkinson: Royal Annals of Ancient Egypt. The Palermo Stone and its associated fragments (= Studies in Egyptology. ). Kegan Paul International, London / New York 2000, ISBN 978-0-7103-0667-8 .

Astronomical dating

- Rolf Krauss: Sothis and moon dates. Studies on the astronomical and technical chronology of ancient Egypt (= Hildesheimer Egyptological contributions. Volume 20). Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1985.

- Ulrich Luft: The chronological fixation of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom according to the temple archive of Illahun (= meeting reports (Austrian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class). Volume 598). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1992, ISBN 978-3-7001-1988-3 .

- Bradley E. Schaefer: The Heliacal Rise of Sirius and Ancient Egyptian Chronology. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy (JHA). Volume 31, Part 2, May 2000, No. 103, pp. 149–155, ( bibcode : 2000JHA .... 31..149S ).

- Rita Gautschy, Michael E. Habicht , Francesco M. Galassi, Daniela Rutica, Frank J. Rühli, Rainer Hannig: A New Astronomically Based Chronological Model for the Egyptian Old Kingdom . In: Journal of Egyptian History , 10 (2), pp. 69-118, booksandjournals.brillonline.com

Synchronisms

- Manfred Bietak (Ed.): The Synchronization of Civilizations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium BC III: Proceedings of the SCIEM 2000 / 2nd EuroConference, Vienna, 28th of May - 1st of June 2003. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-7001-3527-2 .

- Felix Höflmayer: The synchronization of the Minoan old and new palace times with the Egyptian chronology. Dissertation, University of Vienna, 2010 ( online ).

C14 method

- Georges Bonani, Herbert Haas, Zahi Hawass, Mark Lehner, Shawki Nakhla, John Nolan, Robert Wenke, Willy Wilfli: Radiocarbon dates of Old and Middle Kingdom monuments in Egypt . In: Radiocarbon . tape 43 , no. 3 , 2001, p. 1297-1320 ( PDF ).

- Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Andrew J. Shortland: Radiocarbon and the Chronologies of Ancient Egypt Oxbow Books, 2013.

- Hendrik J. Bruins: Dating Pharaonic Egypt . In: Science . tape 328 , no. 5985 , June 18, 2010, p. 1489–1490 , doi : 10.1126 / science.1191410 .

- Uwe Zerbst: Radiocarbon and historical-archaeological dating for the ancient Orient. New developments. In: Studium Integrale Journal. 12th year, issue 1, May 2005, pp. 19–26, ( online ).

- Michael Dee, David Wengrow, Andrew Shortland, Alice Stevenson, Fiona Brock, Linus Girdland Flink, Christopher Bronk Ramsey: An absolute chronology for early Egypt using radiocarbon dating and Bayesian statistical modeling . In: Proc. R. Soc. A . tape 469 , no. 2159 , November 8, 2013, doi : 10.1098 / rspa.2013.0395 ( royalsocietypublishing.org [PDF]).

Archaeological dating

- David O'Connor: Political Systems and Archeological Data in Egypt: 2600-1780 BC. In: World Archeology. 6, 1974, pp. 15-38. ( online )

- Fekri A. Hassan: dating techniques, prehistory. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 233-34.

- Stephan Seidlmayer: Economic and social development in the transition from the old to the middle empire. In: Jan Assmann , Günter Burkard , Vivian Davies (Eds.): Problems and Priorities in Egyptian Archeology . KPI, London 1987, ISBN 0-7103-0190-1 , pp. 175-217.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Thomas Schneider: The end of the short chronology: A critical balance of the debate on the absolute dating of the Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period. In: Egypt and Levante , 18, 2008, p. 276.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 13.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 13 f.

- ^ Francesco Raffaele: All fragments of the Annalenstein after Wolfgang Helck

- ↑ Catch Penny: All fragments of the Annals stone by Wolfgang Helck

- ↑ Cairo fragment (C1) with further sections C2 – C5 and reconstructions / transcriptions

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 19.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 20.

- ↑ a b Beckerath: Chronology of Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 23.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 24.

- ↑ Folker Siegert: Flavius Josephus: About the originality of Judaism (Contra Apionem) . P. 34.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 37f.

- ↑ a b Beckerath: Chronology of Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, pp. 32-33.

- ^ Paul Kunitzsch: The Almagest. The Syntax mathematica of Claudius Ptolemy in Arabic-Latin tradition. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1974.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, pp. 58-59.

- ↑ Chronology of Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 59.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 42f.

- ^ Bradley E. Schaefer: The Heliacal Rise of Sirius and Ancient Egyptian Chronology. In: JHA 31 , 2000, p. 151.

- ^ Bradley E. Schaefer: The Heliacal Rise of Sirius and Ancient Egyptian Chronology. In: JHA 31 , 2000, p. 153.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 43.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 43 and further: Erik Hornung: Investigations on the chronology and history of the New Kingdom. Wiesbaden 1964, p. 15 ff.

- ↑ a b Beckerath: Chronology of Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 44.

- ^ Schneider: The end of the short chronology. P. 283.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 4, p. 44 ff.

- ^ Rolf Krauss: Arguments in Favor of a Low Chronology for the Middle and New Kingdom in Egypt. In: Manfred Bietak (Ed.): The Synchronization of Civilizations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium BC Volume II, 2003, p. 175.

- ↑ Thomas Schneider: The end of the short chronology: A critical balance of the debate on the absolute dating of the Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period. In: Egypt and Levante 18, 2008, p. 287.

- ↑ a b Schneider: The end of the short chronology. P. 288f.

- ^ Rolf Krauss: Sothis and moon dates. Studies on the astronomical and technical chronology of ancient Egypt. 1985, p. 100.

- ^ Schneider: The end of the short chronology. P. 291; Krauss: Sothis and moon dates.

- ↑ Ulrich Luft: The chronological fixation of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom according to the temple archive of Illahun. Vienna, 1992.

- ^ Schneider: The end of the short chronology. P. 290; Air: the chronological fixation.

- ^ LE Rose: The Astronomical Evidence for Dating the End of the Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt to the Early Second Millennium: A Reassessment. In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies 53, 1994, pp. 259 ff .; Schneider: The end of the short chronology. P. 290 f.

- ^ Rolf Krauss: Lunar Dates. In: Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, David A. Warburton (eds.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology. 2006, pp. 395-431. Rolf Krauss: Arguments in Favor of a Low Chronology for the Middle and New Kingdom in Egypt. In: Manfred Bietak (Ed.): The synchronization of civilizations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the second millennium BC Volume II, 2003, pp. 175–197; Rolf Krauss: An Egyptian Chronology for Dynasties XIII to XXV. In: Manfred Bietak, Ernst Czerny (Ed.): The synchronization of civilizations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the second millennium BC Volume III, 2007, pp. 173-189.

- ^ C. Bennet: Review by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, David A. Warburton (eds.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology. 2006. In: Bibliotheca orientalis (BiOr) 65, 2008, pp. 114–122.

- ^ Schneider: The end of the short chronology. P. 292.

- ^ Sturt W. Manning: Radiocarbon Dating and Egyptian Chronology. In: Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, David A. Warburton: Ancient Egyptian Chronology. 2006, p. 333 f.

- ↑ Malcolm H. Wiener: Times Change: The Current State of the Debate in Old World Chronology. In: Manfred Bietak (Ed.): The synchronization of civilizations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the second millennium B. C. Volume III, 2007, p. 29 ff.

- ↑ a b Radiocarbon and historical-archaeological dating for the ancient Orient. New developments. Retrieved September 8, 2014 .

- ^ Radiocarbon-Based Chronology for Dynastic Egypt. Retrieved September 8, 2014 .

- ↑ Georges Bonani et alii: Radiocarbon dates of Old and Middle Kingdom monuments in Egypt. In: Radiocarbon No. 43 , 2001, pp. 1297-1320.

- ↑ Hendrik J. Bruins: Dating Pharaonic Egypt. In: Science 328, 2010, p. 1489 f.

- ↑ For the comparative data see Ian Shaw: The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. 2000, p. 480 ff.

- ↑ Michael Dee, David Wengrow, Andrew Shortland et al .: An absolute chronology for early Egypt using radiocarbon dating and Bayesian statistical modeling. In: Proceedings of the Royal Society A. Vol. 469, No. 2159, 2013 doi: 10.1098 / rspa.2013.0395 ; Full text .

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 4.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 57.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 57 with reference to Herodotus, VII, 1.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 57 with reference to Thucydides , The Peloponnesian War. I, p. 109–110 and Eduard Meyer : Geschichte des Altertums. Vol. IV, 3rd improved edition, Cotta, Stuttgart 1939, p. 568, note 3.

- ^ Theopompos , FGrH 115 F 103

- ↑ Chronology of Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 57 with reference to FK Kienitz: The political history of Egypt from the 7th to the 4th century Berlin 1953, pp. 82–88.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 57 with reference to Isokrates, IV, 140 f., Panegyrikos, chap. 39 and Eduard Meyer : History of Antiquity. Vol. V, 4th, improved edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1958, p. 306, note 1.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 57 with reference to Diodor, XV 29, 38, 41–44 and FK Kienitz: The political history of Egypt from the 7th to the 4th century, 1953, p. 96, note 2.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 57 with reference to FK Kienitz: The political history of Egypt from the 7th to the 4th century 1953, p. 96.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 57 with reference to FK Kienitz: The political history of Egypt from the 7th to the 4th century 1953, pp. 170–173.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 57 and note 238.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 59.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 61 and note 256.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 62.

- ↑ Beckerath: Chronology of the Pharaonic Egypt. Mainz 1997, p. 62 with reference: Based on a Babylonian Chronicle P, published by F. Delitzsch, Abh. Akad. Leipzig January 25, 1907

- ↑ According to the royal chronicle of Asarhaddon: The first battle was fought on the 3rd Du'zu . The beginning of the 3rd Du'zu fell in 671 BC. On the evening of June 23rd and the beginning of spring on March 29th in the proleptic Julian calendar. The time difference to the Gregorian calendar is 8 days, which must be deducted from June 23. Calculations according to Jean Meeus: Astronomical Algorithms - Applications for Ephemeris Tool 4,5 - , Barth, Leipzig 2000 and Ephemeris Tool 4,5 conversion program .

- ↑ 2 days after the second battle.

- ↑ 4 days after the third battle.

- ↑ Thomas Schneider: The end of the short chronology: A critical balance of the debate on the absolute dating of the Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period. In: Egypt and Levante 18, 2008, p. 276

- ^ Ian Shaw: Introduction: Chronologies and Cultural Change in Egypt. In: Ian Shaw: The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford, 2002, p. 13 f.

- ↑ WMF Petrie: Sequences in Prehistoric Remains. In: Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (JRAI) 29, 1899, pp. 295-301. ( JSTOR 2843012 )

- ^ WM Flinders Petrie, James Edward Quibell: Naqada and Ballas. London, 1895. ( archive.org )

- ^ WM Flinders Petrie, Arthur Cruttenden Mace: Diospolis Parva: The Cemeteries of Abadiyeh and Hu. London 1901 ( archive.org )

- ↑ WMF Petrie: Corpus of Prehistoric Pottery and Palettes. London, 1921; languesanciennes.ens-lyon.fr ( Memento of March 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Stan Hendrickx: Predynastic - Early Dynastic Chronology. In: Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, David A. Warburton (eds.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Brill / Leiden / Boston, 2006, p. 60 ff.

- ↑ WMF Petrie: Corpus of Proto-Dynastic Pottery. London, 1953.

- ↑ WMF Petrie: Tarkhan I and Memphis V. London 1913 ( archive.org )

- ↑ Hendrickx: Predynastic - Early Dynastic Chronology. In: Ancient Egyptian Chronology. P. 62 f.

- ↑ Hendrickx: Predynastic - Early Dynastic Chronology. In: Ancient Egyptian Chronology. P. 63; Stan Hendrickx: The Relative Chronology of the Naqada Culture. Problems and Possibilities. In: Jeffrey Spencer: Aspects of Early Egypt. London, 1996, p. 38.

- ^ RL Mond, OH Myers: Cemeteries of Armant I. London, 1937.

- ↑ Werner Kaiser: On the internal chronology of the Naqada culture. In: Archaeologia Geographica 6, 1957, pp. 69-77.

- ↑ Hendrickx: Predynastic - Early Dynastic Chronology. In: Ancient Egyptian Chronology. P. 71 ff.

- ↑ Hendrickx: Predynastic - Early Dynastic Chronology. In: Ancient Egyptian Chronology. P. 75 ff.

- ↑ Hendrickx: Predynastic - Early Dynastic Chronology. In: Ancient Egyptian Chronology. P. 81 ff.

- ↑ Hendrickx: Predynastic - Early Dynastic Chronology. In: Ancient Egyptian Chronology. P. 64 ff .; Hendrickx: The Relative Chronology of the Naqada Culture. In: Aspects of Early Egypt. P. 38 ff.

- ↑ Hendrickx: Predynastic - Early Dynastic Chronology. In: Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Pp. 55-93 .; Hendrickx: The Relative Chronology of the Naqada Culture. In: Aspects of Early Egypt. Pp. 36-69.

- ^ BJ Kemp: Automatic Analysis of Predynastic Cemeteries: A New Method for an Old Problem. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology 68, 1982, pp. 5-15.

- ^ TAH Wilkinson: A New Comparative Chronology for the Predynastic - Early Dynastic Transition. In: Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum (JACF) 7, 1994-1995, pp. 5-26.

Remarks

- ↑ The "White Cross-lined" ceramic mostly consists of sand-hardened Nile clay. The surface ranges from dark red to reddish brown and has a polish. A characteristic feature is the white to cream-colored painting (mainly geometric patterns, as well as animals, plants, people and boats)

- ↑ The "Decorated" pottery usually consists of marl clay that has been hardened with sand. The surface is well smoothed but not polished. The color ranges from light red to yellowish gray. A painting was applied to the surface with red-brown paint. Main motifs are ships, desert game, flamingos, people, spirals, wavy lines and z-lines

- ↑ The "Wavy Handled" ceramic appears from the Naqada IIc period. In terms of quality and processing, it is identical to the "decorated" goods. The surface color ranges from light red to yellowish gray. The wave handle is characteristic.

- ↑ The “Black Topped” ceramic, made of sand-hardened Nile clay, is typical of Naqada I and IIa-b. The main characteristic is the black border on dark red to reddish brown ceramic. The surface is almost always polished.

- ↑ The "Red Polished" ceramic is identical to the "Black Topped" ceramic, except that the black border is missing.

- ↑ The "Rough" ceramic consists of nile clay, which is heavily thickened with straw. The outsides are only roughly smoothed, with a red-brown surface, without polishing.

- ↑ The material of the "Late" ceramics is the same as that of the "Decorated" and "Wavy Handled" goods and includes different types of goods that only appeared in the late Naqada period. In addition, it is partly indistinguishable from the "rough" goods.