Salamis (Cyprus)

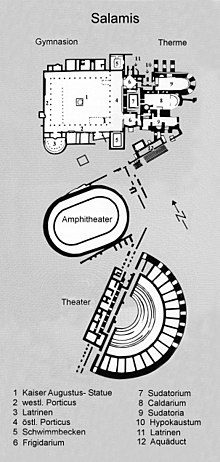

Salamis , Assyrian Ki- (i) -su , ancient Greek Σαλαμίς , Greek Salamina ( Σαλαμίνα ), Latin Constantia , is an Iron Age city kingdom and an ancient city at the mouth of the Pediaios in the east of the Mediterranean island of Cyprus on a wide bay about 6 km north of the today's Famagusta .

Excavation and finds

The ruins of the great ancient city were partially excavated until the war in 1974 under the direction of Vassos Karageorghis . Finds from Salamis and the inland neighboring Enkomi show that both settlements existed in parallel for a short time. Finds from Salamis are exhibited in the nearby museum of St. Barnabas Monastery .

Founding myth

The mythical founder of Salamis was Teukros , son of Telamon , king of the Greek island of Salamis of the same name . He is said to have landed on Cyprus after the destruction of Troy , where Zeus built a temple and married Eune , the daughter of Kinyras . His father-in-law was the father of Adonis , from an incest connection with Eune's sister Smyrna . Teukros founded a city in Cyprus, which he named after his home island Salamis.

history

Since the 11th century BC . BC Salamis had the lead role among the Cypriot city kingdoms held. The initially relatively small city with a necropolis on its western edge expanded from the 8th century BC. On three sides. The old necropolis was built over and a new one laid out in the south, which extends to the monastery of St. Barnabas . Trade relations show the influences of the high cultures of Asia Minor, the Middle East and Egypt.

In the 8th century BC A stronger Phoenician influence is recognizable. David W. Rupp even assumes that these intensive trade relations with the Levant led to the development of the kingdom of Salamis on the model of the Near East. He sees the additions in the royal tombs as a "conscious political statement". Anthony Snodgrass, on the other hand, sees the graves as self-portrayals of long-established established rulers.

The rule of the Assyrians at the end of the 8th century is reflected in the increased occurrence of Near Eastern elements. The leading role of Salamis at the time of Egyptian rule is documented by the coins of King Euelthon (560-525 BC), on which he describes himself as the ruler of the island. The history of Salamis was now more closely linked to that of the whole island than before. She played a role in the disputes with the Persian Empire , in the Ionian uprising and in the disputes over the succession of Alexander the Great .

King Euagoras I was allied with Athens and the pharaoh Hakor (393-380 BC), and he managed at short notice to bring Tire , Sidon and perhaps also Dor under his control. Inscriptions in archaic Cypriot script from Dor could date from this period. The last king of Salamis, Nikokreon , committed suicide with his family in 311/310. 306 BC A decisive naval battle of the Diadoch Wars took place near Salamis , in which Antigonus I, together with his son Demetrios I Poliorketes, defeated the Egyptian general Ptolemy I , who had controlled Cyprus until then.

As the first city in Cyprus, Salamis coined around 515 BC. BC coins.

Under the Ptolemies , Paphos replaced Salamis as the most important city on the island.

From 54 BC B.C. Cyprus becomes provisional, from 31 B.C. Finally Roman colony. Approx. 45–47 AD, Salamis was reached by Christianity during the first missionary journey of Paul and Barnabas, whereby the missionaries turned to the Jewish community there (Acts 13: 5). The city's water supply was ensured by an aqueduct from Chrytoi . Salamis was hit by earthquakes in 332 and 342 AD , the latter connected with a tsunami . According to Cassius Dio's report, Salamis is said to have been destroyed in 115 during the revolt of the Jews against Emperor Trajan , killing 240,000 residents. Under Constantius II it was rebuilt on a limited area and was called "Constantia". At the time of Bishop Epiphanios (368–403 AD), it replaced Paphos as an island metropolis.

In an inscription from the thermal baths of Salamis Justinian and Theodora are praised as innovators of the city. In their time, both the baths and the basilica of Epiphanius seem to have been renovated and embellished. Marble columns were erected in the thermal baths, and a column in the center of the palaestra presumably carried a statue of the imperial couple. The semicircular synthronon was built in the basilica and the floor was covered with white marble slabs. The Hagiasm of Nicodemus in Constantia contains inscriptions and wall paintings from the 6th century , including a Christ head.

Constantia only existed for 300 years. Raids by the Arabs and natural disasters put an end to it around the middle of the 7th century and led to the upswing of the neighboring Ammochostus, later Famagusta .

Kings of Salamis

- Teukros (mythical)

- Euelthon , 560-525 BC Chr.

- Gorgos (Salamis) after the Ionian rebellion (500 / 499–494 BC)

- Euagoras I , 411-374 / 3 BC. Chr.

- Nicocles , 374-368 BC. Chr.

- Euagoras II. 368-351 BC Chr.

- Pnytagoras 351-332 BC BC, King of Salamis, submitted to Alexander of Macedon in 332

- Nikokreon in the time of Alexander

- Ptolemy 80-58 BC BC King of Cyprus, then incorporated into the Roman Empire

Salamis necropolis

Grave 1

With this grave, the detailed investigation of the Salamis necropolis began in 1957. The grave was laid out by making a deep cut from east to west in the clayey rock (all subsequent graves were laid out in the same way). At the western end, the rectangular burial chamber was incorporated (4.70 × 5 × 2 m), the rear side of which was bordered by boulders, while the side walls were plastered and inclined inward. This stabilized the roof, which consisted of long slates of slate. In the middle was the entrance door, which in its outer area possibly had a propylaeum (4.60 meters wide, 1 m deep), of which the remains of two pillars were still found that stood on the outside. The outside of the grave (9.45 m wide) was clad with white limestone blocks and decorated with a frieze on the upper edge (only remains). A long dromos was attached to this facade.

Inside, the grave was robbed, but evidence could be found that there were two different phases of occupation. The first includes a bronze cauldron in which the remains of a burned person (with clothing) were found, as well as a necklace with pearls made of rock crystal and gold. The remains of a pyre were also found on the dromos, on which the deceased was burned (due to the gold jewelry it is assumed that it was a female person) and where small gold disks were also found. Based on the very rich additions, one speculates that this may be the burial of a Cypriot lady of the upper class or even a member of the royal family (princess). In addition to the jewelry items, ceramic vessels of the geometric type were found, which date the grave to the middle of the 8th century BC. Suggest. It was also established that the pottery was possibly of the Euboan style and that accordingly Euboian immigrants had come to Cyprus and brought the pottery as well as the burial practices.

The second burial is a body burial that dates back to the early 7th century BC on the basis of the found pottery (also Euboic). Is dated. Due to the later looting of the grave, there is hardly anything left of this.

In addition to the additions in the grave, numerous items were repeatedly found in the Dromoi in Cyprus . Here, too, two layers containing additions could be identified. Two horse skeletons and traces of a wagon were found in the older shift, both of which had been badly damaged when they were moved aside to bring in the items for the second burial. The second burial consisted of four horse skeletons and the remains of two chariots (only the metal parts were found in situ , the wooden parts are gone).

Although this tomb is not the most outstanding or the best example of the great tombs in the Salamis necropolis, it was the starting point of the excavation activities and cleared the way for the discovery of a complete Cypriot culture, which was mainly characterized by funerary architecture.

Grave 2

Graves 2 and 3, which were discovered in 1962/63, are located at the driveway. In addition to valuable ceramic and silver finds, grave 2 also provides evidence of human sacrifice in the context of the cult of the late 8th and early 7th centuries BC Chr.

During the excavation of grave 2, it was found that nothing of the original tumulus had survived, as it had been removed by agriculture. The excavators had no hope of finding anything in the burial chamber, as it was known beforehand that the grave had been robbed, which turned out to be correct. The only remains that were found next to the penetrated earth were parts of a human skull, bone fragments, ceramic shards, a jug and a silver bowl. From the human bones, the excavator concluded that this was a body burial, not a cremation of the corpse. The burial chamber consisted of a small rectangular room (3.10 × 2.20 m), the walls and floor of which were built from large ashlar stones. The walls slope inwards slightly so that they can hold the ceiling, which is made up of two large blocks. Outside the tomb there is a long dromos and a limestone facade that frames the opening of the tomb. The entrance had been closed with a large limestone block.

In contrast to the burial chamber, the dromos of the tomb contained numerous finds. During the excavation, however, it was found that the finds in different layers could be assigned to different times, so that two different burials were concluded. The older burial probably contained the amphorae on the western side that had not been cleared away for the second burial, as well as some parts of horse bones, pieces of jewelry and parts of a wagon that were found in the backfill layer for the second burial. This first burial is dated (based on the pottery) to approx. 700 BC. Chr.

In contrast, the finds from the second burial are still in situ. Two horse skeletons and the remains of a wagon were found in the southwest corner. Horse A was lying with its head to the west, almost directly in front of the entrance and still had his complete bridle (i.e. all iron parts) - a ribbon that leads from the forehead to the nostrils, blinkers, rings, bridle - and was covered with the wagon. Horse B, on the other hand, was found in a rather unnatural position in the southwest corner and, according to the excavators, was buried alive and pelted with stones (which were found around it). Its bridle had probably thrown off beforehand, because it was found near horse A. In addition, numerous ceramic vessels were found on the southeastern side, which most likely had been filled with food. Using these vessels, the second burial was dated to the end of the 7th century BC Dated.

Above these layers there was a complete human skeleton and parts of another skeleton in the backfill layer, which was probably placed there when the drom was filled.

Grave 3

In contrast to grave 2, this grave still had its original tumulus (although this is no longer preserved in its original height). Due to this very striking landscape feature, this grave was looted several times and examined by the "British Expedition" in 1896, which dug a tunnel into the burial chamber as well as into the dromos. Therefore, many of the finds that were made in 1964 have been disturbed and can only be partially reconstructed. Just like grave 2, grave 3 had a burial chamber (2.95 × 2.40 × 2.80 m), which was protected on the walls and floor with limestone and was covered by two stones. Here the entrance was closed with a large block, but this was first artfully cut into shape.

As a superstructure, the grave had the already mentioned tumulus, which was artfully placed on a round brick construction, which made it 6 m high and which was hollow inside. An unusual construction that the excavators compared to a beehive.

In the dromos , the burial had two horse-drawn teams, but they were badly damaged by the tunnel that was driven through the whole complex. This also included numerous weapons, such as a sword with an ivory pommel, scabbard and leather belt, information about the armament of the late 7th century BC. Give. An amphora placed on the side with the inscription "of olive oil" reminds of an Achaean custom of the dead. In the southern part of the drom there were imprints of wooden furniture (two chairs, bed rails), as well as remains of colored clothing and leather, which probably belonged to the furniture. In the eastern part of the dromos there was also a large heap of ashes that had served as a funeral pyre, but only pieces of charcoal could be found in it.

It is also unusual that a layer emerged under the finds on the Dromos, which must have been another tomb, which was destroyed with the construction of the new tomb and of which only two vessels are still present. However, this is dated to about the same time as grave 3, i.e. that is, they cannot have been far apart in time.

Based on the pottery, the grave is dated to about 600 BC. (End of Cypro-Archaic I / beginning of Cypro-Archaic II) dated.

Grave 31

About a hundred meters west of the large tumulus of grave 3 was another grave, which the excavators only came across through the testimony of a farmer who had excavated numerous stones from the earth in this area.

The grave has the same structure as grave 2 and was also built from the same limestone. The burial chamber consists of irregularly shaped limestone blocks and was covered by 4 panels, two of which were destroyed by looters. Remnants of a white plaster made from lime and earth to hide the irregular walls were found on the walls. The entrance was closed by 4 layers of stone and additionally protected by the surrounding stones.

When the grave was opened from above, it was found that it had already been opened and that soil and backfill material had penetrated as a result. A human skeleton was found underneath, which must have entered the grave through this opening. Some Hellenistic vessels were found in this layer, suggesting that this person was reburied in the tomb.

In the burial chamber, however, there were other burials that indicate at least two occupancy phases. Under the Hellenistic burial, three complete skeletons were found in the middle of the room, surrounded by numerous ceramic vessels. A little further away, three skulls were found, which were probably moved aside for the previous deceased. In addition, right next to the Hellenistic skeleton, another skull and remains of bones were found that had probably been put away with the skull. Below this layer was another one where an amphora with human remains was found. This burial probably also included sheets of gold that were found in the shape of a ball in a small pit below the skeletons. The last burial would have been a cremation, the remains of which were thrown into the amphora after the decision was made to re-use the grave.

In the dromos, the skeletons of two four-legged friends were found directly in front of the entrance. They were leaning towards each other and their back legs were missing (they were probably destroyed during the second occupation of the grave). In their vicinity there were only two iron nails and an iron knife (perhaps for the ritual slaughter of the animals).

In the top layer of the dromos, some human skeletons were found, all of which date from the Hellenistic period, when this area was also used as a cemetery. This dense occupation (6 skeletons inside the dromos) and the few additions made the excavator assume that it could possibly be a war death or an epidemic.

The entire dating of the grave was carried out on the basis of the found pottery and led to the conclusion that the various occupation phases were not particularly far apart and all date to the Cypro-Archaic I period (around the middle of the 7th century BC). .

Grave 19

A few meters away from grave 31, after examining large stones that could be seen on the surface, another grave was uncovered. It was slightly smaller than the previous examples, but had the same structure. The rectangular burial chamber (3.20 × 2.20 m) was clad with reddish limestone, whereby no ashlar stones were used, but irregularly cut stones, whose smooth side formed the inside of the chamber. The ground was not paved, just tamped earth. In the middle of the south wall was the entrance to the chamber, which was closed from the outside with several large blocks, but this did not bother the grave robbers, as they entered the grave from above. Therefore, there are hardly any residues left in situ . Based on the sequence of layers, however, it is assumed that the grave originally had at least two occupancy phases.

The oldest burial consisted of a pit on the northwest side of the grave, in which the remains of a deceased person and some fragments were found. In addition, there are some vessels in the entrance area that could also be part of it. In the dromos, the skeletons of a four-legged friend are definitely included, the hind legs of which were probably lost during the backfilling for the second burial. From this second burial we only have the sequence of layers, which suggests that the grave was opened again, with the first burial being transported into the pit and the second being brought in. The very careful closure of the entrance with several large stones also dates from this time. When dating, one again assumes burials that are very close together. But since not many finds were made, the whole thing is limited to the period between the beginning of the 7th century BC. BC and the beginning of the 6th century BC Chr. A.

Grave 47

Clearly the standard of living of the occupants is discovered in 1964 richly endowed grave 47 , long in the 20 meters and 13 meters wide Dromos four stages in the upstream of the grave chamber Propylaion lead. The chamber (4 × 2.30 m) consists of huge worked stone blocks and was heavily robbed, so that no finds were made inside. They even blasted the ceiling with dynamite to get to the finds.

For this purpose, two horses were found near the Propylaion, connected by a yoke (G + H). One horse was in a normal position while the other was twisted a little so the excavators assumed it was kicking as it saw the first one killed. The iron bridle, as well as the headbands and blinkers (both originally made of leather and covered with gold) were preserved on both horses. Only a drawbar imprint (L: 1.85 m, W: 0.06 m) was preserved from the car. This layer also included four amphorae, which were located on the north and south sides, as well as some ceramic remains that were found along the north side of the drom and in the middle. With the help of ceramics, the grave could be built in the late 8th century BC. To be dated.

The remains of a secondary burial were found about one meter above the dromos floor. Directly on the Propylaeum were six horse skeletons with blinkers and headbands made of ivory and bridles made of bronze . Horses A + B were intended for the first wagon, of which the imprints of the yoke and the drawbar have still been found. Horses C - F were for the second chariot, which probably had two horses on each side of the yoke. Six iron rings were found, probably attached to the top of the yoke (three for each pair). From the position of the horses it could be determined that horses A + B were buried later than the other four because they were lying on their wagons. This burial also includes a vessel with scorch marks and a bone that may have been part of a whip. In addition, a fastening was found that was possibly attached to stones and served as a kind of door protection. The second burial is now in the middle of the 7th century BC. Set.

Grave 50

Near the monastery of St. Barnabas is the grave 50, which is called the prison or grave of St. Catherine (probably a local saint). During the excavations in 1965 by the Department of Antiquities / Cyprus, it was found that this complex had four different construction phases.

Construction phase 1

When the tomb was erected, it looked very much like the other royal tombs. It had a rectangular burial chamber (4 × 2.40 × 2.40 m) and a long drom (28 × max. 13 m). The chamber was built from two large limestone blocks, which were connected in the spaces with plaster and had a gable roof. An elaborate facade was built in front of it, which was twice as thick as the walls of the burial chamber. Some remains of a frieze were found on the facade, which indicated that the upper area had a frieze running around it, which extended into the corners. The courtyard that stretched from the entrance to the corners of the dromos was paved, while the dromos was covered with cement. To compensate for the difference in height between the dromos and the courtyard, there was a large staircase with five steps over the entire width. Nothing is left of the original burial, as the grave was reused several times. But there are two horse burials in the Dromos at this time. They were buried there together with a wagon (of which only impressions of the drawbar and yoke remain). In the horses, too, only iron snaffles were found on metal parts. A group of vases on the north side is also part of it, based on which this phase is dated to the Cypriot-Archaic II period (beginning of the 6th century BC).

Construction phase 2

During this time, the system was completely redesigned. The stairs have been removed, for this purpose two cheek walls will be installed 5.40 m away from the entrance to the right and left to create an additional space instead of the courtyard. This room was then covered with a barrel vault. In order to make the facade even more impressive, a surrounding frieze was attached to the upper end and equipped with a propylaeum, of which the remains of 4 columns were found. In this phase of monumentalization, the grave was probably no longer used in the actual sense, but a sanctuary or a heroon was set up . A pit that was found in front of the new facade and which was filled with stones, ceramic shards and a clay pipe and was probably intended for collecting rainwater also dates from this time. The whole complex is dated to Roman times based on the small finds and the technique of the barrel vault. It is assumed here that it was erected between the end of the 3rd century AD and the first half of the 4th century AD. The hypostyle hall may have collapsed in a major earthquake in the middle of the 4th century AD.

Construction phase 3

After removing the pillars in front of the entrance, a two-step staircase was built instead, flanked on both sides by ashlar blocks. This no longer ended at a threshold, instead a portcullis was built in instead of a door. Several burials were found on top of this layer. Once a pit that was built against the facade of the vaulted chamber, in which the remains of eleven adult skulls as well as countless bones and three children's skeletons were found. Three clay lamps and an unguentarium were found in this chamber made of rectangular blocks . In addition, eight pits were found distributed over the entire dromos, in which there were vessels that probably contained all child and newborn burials. An adult burial with seven clay lamps, which was probably completely destroyed by the renovation work of construction phase 4, was found in the northeast. Based on the small finds, this construction phase is dated to the 4th to 7th centuries AD.

Construction phase 4

In the final phase, the trap door was removed and a wooden door was inserted. Five steps were added to the staircase. A bench was built along the north and east walls, which could only be entered from inside the dome, so that a new entrance was created at this point. The drain, which ended in a pit in construction phase 2, was now directed into the interior of the dome with the help of drainage pipes, where a storage vessel was placed under the floor. The actual burial chamber in the background was given a new entrance and a wooden door. This phase could be dated to the Middle Ages through a coin find by Alexios I (1081–1118) .

Grave 79

In 1966, grave 79 was found northeast of grave 47 . It contains the richest grave equipment. The architecture of the tomb consists of a superstructure in which the burial chamber is located and a long access (dromos). The burial chamber was reused in Roman times and burial niches were added to the architecture. Therefore, only the remains of the original grave goods are probably left, which are in the anteroom. The finds in the dromos suggest two burials; one from the end of the 8th and one from the beginning of the 7th century. Both burials were placed in the middle of the drom on two chariots (a hearse and a chariot) with accompanying horse skeletons. For the secondary burial, the wagons placed in the dromos were cleared to the side (the chariot could still be pushed, the wheels of the hearse were no longer functional). The associated horse skeletons were severely damaged. In contrast, the horses of the second burial were found in situ .

First burial

It is believed that the first burial originally had six horses, two for the hearse and four for the chariot. Because although only minimal skeletal remains were found, the animals' decorations were found in the north corner of the facade, which was probably placed there when the drom was cleared for the second burial. The chariot that goes with it can still be identified very well, as it has been preserved very well.

dare

Although only the impressions in the floor of the wooden pieces have been preserved, it was still possible to reconstruct the very splendid furnishings. It consisted of an axle to which the two wheels were attached. At the end, the axis was equipped with a small bronze sphinx head (including a headscarf and inlaid eyes), above which a small warrior figure (H: 37 cm) was sitting on the axis split pin. This had a rattle inside so that it could make noises every time the wheel turned, and was completely clothed with armor, chiton , spring helmet and a sword under the right arm. The wheels had ten spokes that were attached to the wheel (no metal tires) by two iron nails. The drawbar was then attached to the axle, the rear ends of which were closed off by oval bronze disks. On these was the representation of a winged lion trampling an enemy. Between the axle and the drawbar was the car body (W: 68 × D: 85 × H: 44 cm), which had a wooden railing and otherwise probably consisted of wicker (no longer preserved, only marks in the ground). It was separated in the middle to have space for the driver and warrior. At the end of the two drawbars was the large yoke, which had four bronze rings to attach the reins, as well as four bronze disks that tapered upwards in a fan shape and indicated a floral decoration. The accompanying horses were also magnificently decorated. They are assigned the following pieces from the north corner:

Breastplates - (4 pieces) semicircular bronze disks decorated with various figures. These consist of 2 rows, arranged one below the other, which show human and animal figures as well as hybrid creatures from oriental mythology. In the middle there is a winged sun , under which there is a tree of life under which a winged man with a fawn is in his arms.

Lateral plates - (2 pieces, were only carried by the outer horses) round bronze plates with a long rectangular bronze holder. The round piece had a depiction of the naked, winged goddess Ishtar , who holds a lion on each hand, which are attacked by griffins and stands on two lions with a calf in their mouth. The whole is crowned by a winged solar disk with a Hathor head in the middle. The representation is surrounded by an animal frieze (which is also on the bracket).

Headbands - (4 pieces) elongated bronze plates. They were decorated with five rows of three figures each. First came lions, then Uraea, then came a large winged sun under which there were a number of male figures with headscarves. The last row consisted of three naked female figures with hathor braids. They all had an eyelet for attachment at the top.

Blinders - (8 pieces) elongated bronze plates. The pieces had the representation of a lion attacking a bull. There is only one exception, and a winged sphinx attacks an African lying on the ground.

All pieces were carried out by driving work and have a very high level of creative ability. Of course, they previously had all the leather strips that made it easier to attach them to the horse's body and also protected the horse from abrasions. In addition to the pieces mentioned above, bronze bells were also found, which were probably attached to the horses, but details are not known.

Hearse Γ

The second vehicle from this first burial was in a very poor condition. It consisted of a wooden support frame with a platform on which the deceased's coffin lay. The frame was decorated with lion heads on both sides, which could indicate that it was only used for ceremonial occasions. Of the horses belonging to it, not as much equipment was found as in the first wagon. But there were two headbands too many that also had a different image.

Headbands - (2 pieces) elongated bronze plates. On them the winged god El could be seen twice one below the other, only separated in the middle by a winged sun. A large lotus flower was found in the lower area.

The assumption that it belongs to a warrior's grave would have fitted very well with this very rich equipment of the wagons and horses, but unfortunately only a bronze spearhead and the remains of a silver shield hump were found among the additions. The explanation for the lack of this equipment could be the subsequent burial, in which these things were lost. There are several other finds that make this first burial the richest burial in all of Cyprus. Because in addition to the bronze accessories of the horses already mentioned, there were other items.

Bronze kettle with an iron tripod

One of the most extraordinary pieces is this bronze kettle (diameter: 65 cm, H: 51 cm), which stood on a tripod. At its upper edge he had twelve namely protomes, eight grasping protomes and two bearded bird men and two sphinxes with tufts on the head. They were attached from the outside and a sphinx and a birdman each look into the cauldron, the other two look away. The kettle was completely filled with sixty ceramic vessels, v. a. Pitchers. They were all plain-ware vessels, some of which were thinly coated so that they might imitate metal. The tripod consisted of a double ring and three legs, each of which consisted of three rods. The bars are decorated in the middle with a lotus blossom and their surface imitates an animal's hoof.

Bronze kettle

Directly next to the first boiler was a second, smaller one, which was also much worse preserved. It had a tall, conical base and two handles. The handles were specially decorated. At the top were three bull protomes each facing inwards. The handles are attached by small plates, on the outside of which a hathor head with a winged sun is attached.

There were also a pair of fire rams in this area, shaped like a ship, and twelve skewers that were tied together with rings and had two handles.

In addition to the many metal objects, there was also a lot of furniture in the dromos that might have been needed for life in the afterlife. We are not aware of such rich gifts from any other Cypriot grave.

Throne Γ

This chair (H: 90 × L: 50 cm × W: 59) was made of wood, but that has largely passed. It was adorned with ivory plates showing plaited ribbon motifs. The backrest was very thinly covered with gold. Nothing has been found of the seat, but it is assumed that it consisted of strips of leather. In the vicinity of the chair there were two ivory plates, which show a winged sphinx with the crown of Upper and Lower Egypt and must have once had blue inlays. Due to the circumstances of the find, one would like to assign them to the throne.

Throne A and chair B

This chair (H: 75 × L: 58 × W: 40 cm) was also made of wood that had passed away. But it was completely covered with silver, which is oxidized, but remains could still be found. He too had inlays made of ivory and blue glass paste. A small stool (H: 21 × L: 24 × W: 19 cm), which was also made of wood and was covered with thin silver plates, belonged to this chair.

bed

In front of the chairs were pieces of ivory that could be reconstructed into a bed (W: 1.11 × L: 1.89 × H: 31 cm). The wooden parts that make up the frame are gone. Some ivory plates were found in the area. Three were attached to the back of the bed. The first showed six seated figures of the god Heh , who holds the tree of life in his hand. The second frieze showed stylized plants. The third frieze has three pairs of sphinxes facing each other.

A few other ivory pieces were also found. One is an S-shaped leg that ends in a cat's paw. The cat's paw has cavities in which the claws were, but they are no longer preserved. They also found an incense holder that looks like a stylized plant.

In the north of the Dromos numerous ceramic vessels were found at both burials, mainly small, flat bowls, some of which still contained leftovers (eggshells, fish bones, chicken bones).

Second burial

The second burial was much better preserved than the first because it was brought up later and not disturbed. Here too, two wagons and accompanying horses were found.

The chariot Δ is a biga , a two-wheeled chariot pulled by two horses. Here, too, the car body (W: 90 × L: 72 × H: 25 cm) was divided into two parts for warriors and drivers. At the far end there was a wooden hatch. The car had ten-spoke wheels. As with car B, four floral decorative elements were attached to the yoke. The construction of hearse A is similar to that of Grave 2 and is much worse preserved. The horses belonging to the wagon were found in situ, with complete accessories. They had bronze blinders, headbands, breast plates, and side plates. They were all made by driving, but were not as splendidly designed as at the first burial. Only the side panels could have a huge scarab beetle, while the other pieces only had ornamental decorations.

With this rich decoration of the grave, the necropolis of Salamis and above all grave 79 are among the most outstanding examples of an early Iron Age burial in the Mediterranean area.

Comparative examples

In order to be able to put the pieces found in a historical context, it is helpful to compare the individual pieces / find circumstances with finds / burials at the same time.

Grave Shape - The Salamis Necropolis has various shapes of graves, the main feature of all graves being a small rectangular burial chamber lined with limestone blocks and provided with a facade. In the entrance area they all have a more or less long dromos. In the individual cases they are designed differently, which could indicate a different time or social position. Grave 3, with its tumulus, has a shape typical of the time, as we can also find it in the Gordion cemetery . The systems there are much larger, but have a very similar structure. Whereas the graves in Eleuthera / Crete are more reminiscent of the architecture of the other graves. Also the Etruscan tombs of the 8th and 7th centuries BC BC have a lot in common with the present structures.

Chariot grave - This term describes a mostly monumental grave to which, in addition to numerous grave goods, chariots (some with horses) were added. We have the best contemporary examples of such a burial from the Northern European area of the Hallstatt period . The graves there are much more monumental, but they too had carriages, but without the associated horse burials.

Horse burials and harness - In every "royal grave" on Salamis there were skeletons of four-legged friends in the dromos. The tradition of horse burials can also be found in other regions at the same time. The (regional) closest example is the tumulus grave complex KY in Gordion . There the skeletons of two horses were discovered on the eastern wall of the burial chamber. These were burned together with their accessories and represent a singular exception in the area of the necropolis of Gordion, so that the excavators suspect that it is not a local Phrygian burial, but an immigrant. The burial dated to the early 7th century BC. Another, albeit older (late 10th century BC) burial in the so-called Heroon of Lefkandi contained four horse skeletons in a burial chamber, of which the snaffles were still preserved in the mouth. Another burial, which is known from the Greek area, is not archaeologically comprehensible, but only in writing. It is the burning of Patroclus in the Iliad . There the dead is cremated together with horses, numerous gifts and horses (Iliad, XXIII, 171–172). In contrast to full horse burials, there is also the tradition of loose burial of the horse harness, which is reflected in the examples mentioned, but has also been passed down from Etruscan graves.

Driving work of the bronze horse harness - The representations on the individual pieces are reminiscent of the oriental art of the Middle East, especially the northern Syrian art of that time. The Phoenicians resident there combined the elements of Assyrian art with Egyptian elements and sold them throughout the area. But you can also find some elements that are reminiscent of the art of Urartu . In both regions, of course, the predominant influence of the Assyrians, whose gods are depicted on some of the pieces. What is rather untypical for this region, however, is the killing or trampling of the enemy , which is only known from Egyptian iconography. Just as of course the representation of the Sphinx , which was known in the Oriental / Phoenician, but is still of Egyptian origin.

Ivory furniture - Just like the bronze pieces, the representations on the ivory plates are also heavily influenced by Assyrian / Phoenician / Egyptian art. Just the representation of various Egyptian gods with their matching attributes suggests that they must have been very knowledgeable craftsmen. Here, too, we have representations of sphinxes with the double crown , for which there are very nice comparative examples from Nimrud (Metropolitan Museum, Inv. Rogers Fund, 1954 (54.117.1); London, British Museum, Inv. ME 134322). Although the site is the capital of the Assyrian Empire, it is again assumed that the workshops are of Phoenician origin.

Bronze cauldrons and roasting utensils - In contrast to the bronze horse utensils , which can be easily placed in the Assyrian-Oriental area thanks to its iconography, the appearance of large bronze cauldrons with griffin protomes is rather unusual for this room. These cauldrons are more likely to be found in the tombs of the Aegean and Etruria. It is the same with the skewers and firebacks, which we mainly know from burials in the Hallstatt period, from Palaepaphos / Cyprus, Argos / Peloponnese and the Etruscan graves.

Human sacrifice - When the dromos from grave two was filled up, two people were probably buried with, from which one could conclude that this was human sacrifice, although this could not be determined with accuracy. The burial in Eleutherna on Creteoffers parallels to this finding, where a man may have been given as a sacrifice in a cremation grave. Here, too, the assignment is not 100% secure. The primary reason why archaeologists gladly accept human sacrifice at this time, is to describe the combustion of Patroclus in the Iliad of Homer . There, twelve Trojan youths were put on the stake with the dead, who had previously beenstabbedto death by Achilles (Iliad, XXIII, 175–177).

In summary, it can be said that the Salamis necropolis is so important because it has numerous finds from a time from which we otherwise have little material legacy. It also represents the peculiarity of Cyprus as a point of intersection between cultures, as you could see influences of different cultures from the entire Mediterranean area. One would like to bring these burials in line with the descriptions of Homer , who describes the burning of Patroclus . Here, too, numerous gifts were given to the deceased, as well as horses and people. That would make it easy to classify. In contrast to the described burial of the Iliad, the graves on Salamis are complete burials and not burns. But one could at least assume that the tradition of putting numerous things into the graves of the deceased was quite widespread.

Cellarka necropolis

About 400 m south of the necropolis of Enkomi / Salamis is the Cellarka necropolis, a complex of underground graves that was only partially opened up between 1890 and 1960. So far, more than 114 rooms carved into the sandstone have been uncovered. The entrances to the rectangular chambers, which are located close to one another and one below the other, lead via steep stairs, dromoi and shafts. Low platforms on which the dead could be placed were discovered in some rooms. It is believed that the burial chambers date from the beginning of the 7th to the end of the 4th century BC. BC, partly over generations, were occupied by the general population, probably also by the middle class of the city. Ceramic goods, jewelry, knives, mirrors and coins were found.

Almost all of the graves were looted in the 19th century. The discovery of five portrait busts of the dead and their personal belongings is reported from a grave. The only unopened grave room (grave 21) was closed with stone slabs and lined with large rectangular stones on the inside. Four dead had been laid in stone niches and on the floor of the room, the grave goods including a horse and rider figure, a lamp and an incense burner were at their feet. In an adjoining chamber, nine dead were found carefully piled up on two stone couches.

Famous residents

- Epiphanius of Salamis , 315–403 AD

literature

- Vassos Karageorghis: Salamis. The Cypriot metropolis of antiquity . Bergisch Gladbach 1970.

- North Cyprus Museum Friends: North Cyprus, Mosaic of Cultures , Nicosia; Publisher A Turizm Ltd. Sti., Istanbul; ISBN 975-7528-94-3 .

- Vassos Karageorghis: Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis 3, Salamis 5 , Nicosia 1973.

- Vassos Karageorghis: Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis 1, 3 Salamis 3 , Nicosia 1967.

- Vassos Karageorghis: Salamis - Pearl in the East . In: Katja Lembke : Cyprus Island of Aphrodite , 2010, pp. 44–51.

- Patrick Schollmeyer: Ancient Cyprus . Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2009.

- Vassos Karageorghis: Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus . McGraw-Hill, New York 1969.

- Vassos Karageorghis: Early Cyprus - Crossroad of the Mediterranean . The Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 2002. ISBN 0-89236-679-6

Web links

- Famagusta City Guide

- Salamis Famagusta

- Finds from Salamis in the British Museum

- Cyprus Web Project Enkomi-Salamis ( Memento from July 10, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (Version from archive.org)

Individual evidence

- ^ Velleius Paterculus . Historia Romana 1.1.1

- ^ Rupp, DW 1988 The "Royal Tombs" at Salamis (Cyprus): Ideological Messages of Power and Authority. Journal of Mediterranean Archeology 1/1, 1988, 111-39

- ^ David W. Rupp Vive le roi: The Emergence of the State in Iron Age Cyprus. In: DW Rupp (Ed.), Western Cyprus: Connections. Studies in Mediterranean Archeology 77. Göteborg, Paul Astrom's Forlag 1987, 156

- ^ Anthony Snodgrass, Cyprus and early Greek history (Fourth annual Lecture on History and Archeology). Nicosia: Cultural Foundation of the Bank of Cyprus 1988 .: 10-11

- ↑ Archived copy ( memento of the original dated August 8, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ AHS Megaw, Byzantine architecture and decoration in Cyprus: Metropolitan or provincial? Dumbarton Oaks Papers 28, 1974, 71

- ↑ On Constantia cf. in detail Eugen Oberhummer : Constantia 5 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume IV, 1, Stuttgart 1900, Col. 953-957.

- ↑ a b Vassos Karageorghis: Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, 1969, p. 26

- ↑ a b Vassos Karageorghis: Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, 1969, p. 27

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis (1967), Excavation in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), p. 8.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis (1967), Excavation in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), pp. 6-7.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis (1967), Excavation in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), p. 10.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis (1967), Excavation in the necropolis of Salamis, pp. 9-10.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis (1967), Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), p. 8.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavation in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1973, p. 25.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavation in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1973, pp. 28-29

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavation in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1973, p. 33.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavation in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1973, p. 53.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 54

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 55.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, pp. 56-57.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 57.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 58.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 69.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 70

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 71

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 73

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 74

- ↑ a b c Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 79

- ^ A b Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 88

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 78

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, pp. 94-95

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 96

- ^ A b Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 105

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 114

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, pp. 96-97

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 102

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 115

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 99

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, pp. 104-105

- ^ A b Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, p. 116.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis I (Text and Plates), 1967, pp. 100-101

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis: Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis , 1973, p. 11.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, p. 78

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, p. 79

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, p. 80

- ↑ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, pp. 87-88

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis: Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis III , 1973, p. 77.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, p. 87

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, p. 97

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, p. 91

- ↑ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, p. 96

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, p. 93

- ↑ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, pp. 95-96

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis: Excavations in the necropolis of Salamis III , 1973, p. 13.

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, p. 85

- ↑ Young, RS, The Campaign of 1955 at Gordion, Preliminary Report, AJA 60, 1956, p. 266

- ↑ Soi Agelidis, Tod und Jenseits, in: Etrusker in Berlin, 2010, p. 41

- ^ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, p. 89

- ↑ Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis: recent discoveries in Cyprus, pp. 90–91

Coordinates: 35 ° 10 ′ 51 ″ N , 33 ° 54 ′ 6 ″ E