Speedometers

| Names of speedometers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horus name |

ḫ3j-m-M3ˁt-sšm-t3wj Who appears as Maat , head of the two countries |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Mrj-M3ˁt-s3ḫ-prw-nṯrw The beloved of Maat, transfigured (through) the godhood |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

ḫwj-b3qt-w3f-ḫ3swt The ruling king who conquers the foreign lands |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

Jrj-m3ˁt-n-Rˁ Executor of justice , a Re

Jrj-m3ˁt-n-Rˁ Executor of justice, a Re |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

(Djed Hor setep en ini heret) Ḏd Ḥr stp n jnj ḥrt Horus says: [He wants to live], the chosen one of Onuris |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Greek Manetho - variants : |

Ταχὠς (speedometer), Ταὠς (Taos), Θάμῳ (Thamus) Africanus : Teos Eusebius : Teos Eusebius (arm. Version): Teos |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

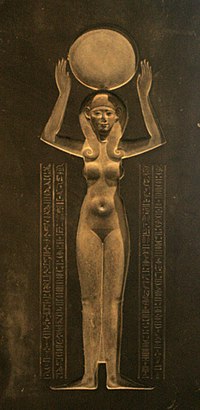

Sarcophagus cover with Tachos name ( Louvre ) (It is not the sarcophagus lid of the Pharaoh Tachos). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tachos ( ancient Egyptian Djedhor, Djedho ) was the Greek name of the second ancient Egyptian pharaoh (king) of the 30th dynasty . After his coronation as Pharaoh, his reign is probably from 360 to 359 BC. To apply. His father Nektanebo I appointed him during his reign probably in 363/362 BC. To co-regent . Some Egyptologists include the duration of dual rule in the reign of Tachos. The ancient Egyptian currency was introduced during this period .

He was the first pharaoh after Apries who, after a good two centuries , planned and began a campaign in the non-Egyptian region of Syria - Palestine . Tachos thus tied in with the old traditions of Thutmose III. who led his successful campaigns in the areas of Retjenu due to the foreign threat .

Shortly before the end of the advance to Phenicia and the associated prospect of a final defense against the Persian threat, Tachos was ousted by an uprising in his own country and replaced as Pharaoh by Nectanebos II . Tachos was the last native king to lead an offensive against the Persians outside Egypt.

Ancient name derivations

Djedhor

Tachos The ancient Egyptian proper name "Djedhor / Djedho" was reproduced in the Greek language among other things in the variants "Tachos", "Thamaus", "Thamus", "Taos" and "Teos". Plato referred in his reports to a "Thamus" who appeared twice as a personal name in ancient Egyptian history. Plutarch mentioned "Thamus" in connection with Tiberius .

The author of a collection of lists of wars, Polyainus , reports on the other hand about the Athenian strategist Chabrias , who gave advice to an ancient Egyptian king "Thamus" who was in financial difficulties. Chabrias, who lived around 357 BC. Died, was first general of the pharaoh Hakor and then contemporary Tachos. The "Thamus" mentioned by Polyainos always appears in other sources as Teos or Taos.

Tjaihepimu

Alfred Wiedemann refers to another derivation of the name. The name of the ancient Egyptian general " Tjaihepimu " (ancient Egyptian: Ṯ3j-Ḥp-jmw ), father of Nectanebos II and brother of the speedometer, was also read in the Greek translation as "Thamus" or "speedometer".

In the Greek version of the demotic papyrus Dream of Nectanebos , a "speedometer" in the form of the name "Samaus" is mentioned as the "father of Nectanebos II". The term "Samaus" is another variant of the name that refers to the literary terms "Thamaus, Thamus" and related to "Taos", "Teos" and "Tachos".

supporting documents

The evidence of contemporary evidence is poor due to the short period of government. The expansion of the Chons Temple in Karnak is documented as construction activity , on whose north wall Tachos built a chapel . In addition, there are restoration inscriptions from him in the Chons Temple . There are also fragments of a relief from Qantir and fragments of a naos .

Other finds are parts of inscriptions from Athribis , Tanis and Tura as well as a stone block from Matarije and a bowl from Memphis . There was also mention of the name of speedometers on a pot lid and its coins.

In epitoms of Manethos Aegyptiaca , speedometers are listed in the form of the name “Teos” with a reign of two years. Manetho counted him among the three kings who came from Sebennytos . In the pharaonic lists of the Demotic Chronicle , Tachos is named as the sixth legitimate pharaoh and eighth ruler after the Persians with a one-year reign after the first Persian rule .

family

Tachos, son of Nectanebos I, came from an immigrant Libyan family from Sebennytos. His grandfather , who had the same name, was responsible for military matters as a general under Nepherites II at the latest . He was certainly not uninvolved in the overthrow of the Mendesian pharaoh Nepherites II (379 BC), since his son Nectanebos I took over the throne with the help of Chabrias and deposed Nepherites II. Chabrias was already under Pharaoh Hakor (ruled 391 to 379 BC) in an advisory capacity responsible for diplomatic relations between Egypt and Athens .

The Egyptologists disagree about the mother of Tachos. Udjaschu is seen on the one hand as a possible mother of Nectanebo I, on the other hand as his wife. Another named wife of Nectanebo I is Ptolemais, who is in part assumed to be the daughter of Chabrias. It is not yet clear whether there were other siblings besides his brother Tjaihepimu. A wife of the speedometer is not occupied.

Domination

Co-regent and Pharaoh

Nectanebos I made preparations for military action against the Persians during his reign. Due to his old age, he made his son Tachos co-regent at the end of his reign. In 360 BC BC Nectanebos I died. The exact date of the end of his reign could be determined indirectly from the demotic papyrus Dream of Nectanebos . Only the night from July 5th to 6th in the year 343 BC. Chr. Corresponds in the Julian calendar with the information given in the papyrus regarding the full moon night of the 16th year of the reign of Nectanebos II. In the demotic chronicle , Nectanebos I received an overall very poor assessment as a "greedy pharaoh" because of the reduction of temple treasures he was responsible for :

“ IV.4 To him who is ruler on (today) day, namely Nechetnebef , one says: He is the one who has given up the possessions of Egypt and all temples, IV.5 in order to produce money ( pieces of silver). It is as if one were to say "He did not act as a man in his time", that is, as if one were to use the name " Vulva ", which is an insult for a woman, to Nechetnebef . "

The negative evaluation of Nectanebo I includes, among other things, the co-reign of Tachos, who in the demotic chronicle is the only ruler to have both the titles “King” and “Pharaoh”. In particular, the statement that Nektanebos I. did not act as a "man" refers very clearly to Tachos, who as co-regent was already responsible for financial matters. After his official coronation as Pharaoh, which fell in the year of a lunar eclipse that was also observed in Egypt , he continued the previous policy on his own, which was jointly adopted in advance by Nectanebo I and Tachos regarding the support of rebellions by satraps of Asia Minor against the Persian great king Artaxerxes II was applied. For example, Rheomithres , envoy of the renegade satraps, received 500 talents silver and 50 warships to engage the Persians in combat. As security for the valuable donations, Rheomithres is said to have left his wife, children and the children of his friends at Tachos. Rheomithres nevertheless broke his oath and allied himself with Orontes in order to defer to Artaxerxes II and then to hand over the 500 talents of silver together with the warships.

Preparations for War

Around 360 BC Tachos introduced the gold stater as the first ancient Egyptian coin and thus laid the foundation for the coinage in ancient Egypt. The reason for the introduction of the gold stater was the remuneration of the numerous employed mercenaries who recruited Tachos for the planned campaign against the Persians.

A short time later, on the advice of his Greek adviser Chabrias , Tachos equipped the army for the campaign against the Persian Empire. Tachos had raised the financial means for this military operation on the one hand by selling further temple treasures, on the other hand he followed the advice of Chabrias to reduce the income of the temple and priesthood to a tenth. The naukratis decree issued by Nektanebos I. expanded speedometers to include all shipping and all goods manufactured in Egypt. The changed financial conditions meant that the royalties awarded by Nektanebo I to the Neith temple in Sais also went to the royal budget.

Although the priesthood expressed their displeasure at this practice, the temples were usually generous in the spoils of war after battles were won. In the demotic chronicle, Tachos received a similarly negative description as his father:

“ IV.16 The master builder's yardstick, that is: He who is on the way, who builds for his father / who his father built. It is one year that he will be allowed to spend in power, IV.17 namely Pharaoh Teos, who will march according to the standard of his father. "

Attack against the Persian Empire

Tachos, who at first patiently observed the events in Phenicia and only supported them with financial aid, seized in 359 BC. Due to the lack of success in the context of the satrap revolts against Artaxerxes II. In his 46th year of reign now the initiative himself to use the still existing weakening with an attack of his troops together with Agesilaos and Chabrias. Athens, which had alliance-like relations with the Persians, had not complied with the request for military support, but allowed Chabrias to participate on his own. The Babylonian sources indicate that the attack on the Persian Empire fell in a leap year on the Babylonian calendar ; the leap month Addaru II had on 23 March and the subsequent first month Nisannu on 22 April started.

The negotiations between Tachos and Maussolos , which had been in existence since around 362 BC, were more successful . Supported the satrap revolts. Due to his efforts and extensive financial concessions by the Egyptian Pharaoh, the Spartan king Agesilaus was persuaded to form an alliance. According to Diodorus, Tachos had raised an army of around 100,000 soldiers made up of 20,000 Greeks and 80,000 Egyptians. Among the 20,000 Greeks there were 10,000 mercenaries who were to fight in the Egyptian infantry , 1,000 of which were hoplites from Agesilaus, who the Spartan king brought with him from his homeland two years after the second battle of Mantineia . Thus the size and composition of the army corresponded to the army that Nectanebo I used during his battle in 373 BC. BC mobilized. Tachos, who, as was customary in the past, wanted to lead the high command of all troops, did not react diplomatically to Agesilaos, since Agesilaos had expected the high command, but was now only awarded the supreme command of his Greek units.

Chabrias agreed to take command of some 200 well-equipped Egyptian ships. The fleet was probably divided into units of larger triremes and fast galleys with a crew of 30 rowers, who, according to Diodorus, were also employed in this number under Nectanebo I in 373 BC. Were used. The Egyptians also had an excellent level of education thanks to the skills they had acquired in the Persian fleet during the first Persian rule . Chabrias traveled to Egypt before the planned attack and from there set out by sea in the direction of Phenicia to assist Tachos in his activities. Nektanebos (II.) Was given the task of advancing overland with the Machimoi to the Chor region , in order to later unite with the troops of Tachos.

The end of the rule

Tachos 'brother Tjaihepimu, who had been installed as governor in Egypt, took advantage of Tachos' absence to allow his son Nectanebos II to succeed the throne as the new pharaoh with the consent of the priests. Agesilaos accepted Nectanebos II's offer to switch to his side and use him to take action against speedometers. Chabrias, however, as agreed, kept his promise to Tachos until he escaped.

The sources of ancient historians unanimously confirm a successful rebellion against speedometers. The triggering reasons for the inner-Egyptian unrest, however, are in the dark. It is by no means certain that Tachos was deposed due to the possibly dissatisfied priesthood. The range of possible causes is complex. It has not been established whether the priesthood actually acted against the tax policy. Not to be underestimated are the effects of tax policy with regard to the lower income brackets, where a further potential risk can be seen. Likewise, Tachos could have come into the focus of criticism because of excessive losses in his military advance.

It cannot be ruled out, therefore, that the Persian Prince Ochos , who took military action against the satrap revolts and Tachos while his father was still alive, brought the Egyptian Pharaoh into a threatening situation with a successful counter-offensive, which may have caused the Egyptian General Tjaihepimu to do his Son of Nectanebo II to hand over high command. Chabrias returned to his homeland after the pharaoh's flight, probably through the intervention of Artaxerxes II in Athens. Since different versions of the ancient historians are available about the events, the actual processes remain unclear. The main sources on Tachos 'Persia campaign and disempowerment are Xenophons , Plutarch and Cornelius Nepos ' biographies of Agesilaos as well as information in the 15th book of Diodor's world history.

Xenophon (426 to 355 BC)

In Xenophon's story, Tachos was planning a war against the Persians four years before the death of Agesilaus (359/358 BC). Agesilaos was delighted to be called by Tachos, as the latter promised him supreme command over the troops. Upon his arrival, Agesilaos discovered that Tachos had taken charge of the attack, which is why Agesilaos felt deceived, but accepted the rank assigned to him. Then it happened that parts of the Egyptian army stayed away from their king. The insecurity that arose in the troops of the Egyptian army led to numerous other deserters .

Tachos, now without a functioning army, fled to Sidon in the Phoenician exile . The army, split into two camps, had to decide which king to follow. Agesilaus decided in favor of the Egyptian king who, in his opinion, would be a faithful follower of Sparta in the future. With this king, Agesilaus went against the enemy of the Hellenes and defeated him. He helped the (Egyptian) rival, who raised large sums of money for the Lacedaemonians , to the throne. After that, Agesilaus set sail despite the winter in order to confront the enemy in the coming summer.

Cornelius Nepos (about 100 to 25 BC)

The records of Cornelius Nepos only indirectly testify that the speedometer was set. The campaign is not discussed. Agesilaus moved to Tachos at the age of 80 to support the Pharaoh. Upon his arrival, Egyptian emissaries brought gifts, but Agesilaus largely refused to accept them; except for the food and ointments, he let the rest go back. Without further details, Nepos describes that "King Nectanabis gave Agesilaos 220 talents". With these gifts Agesilaus set out from Egypt to bring them to his people. In the Menelaus port, between Cyrene and Egypt, Agesilaus died of an illness. His body was taken to Sparta.

Diodorus (1st century BC)

According to Diodor's remarks, Tachos had set out with an army made up of 10,000 selected Greek mercenaries and an infantry consisting of 80,000 Egyptian soldiers. With this measure, the Pharaoh acted against the advice of Agesilaus, who had recommended Tachos to stay in Egypt and let his generals conduct the fighting. While the battle-ready army camped near Phenicia, a general left in Egypt rebelled (according to other sources, this was Tjaihepimu). His son Nektanebos II was able to win over the troops from Tachos, who had orders to besiege the cities in Syria. From these actions a major war developed. After bribes and gifts, Nectanebos II gained supreme command of the entire Egyptian army, with which he retreated to his homeland to conquer Egypt. In the meantime, Tachos traveled to Artaxerxes II via Arabia and apologized for his attacks against the Persians. Artaxerxes II forgave him and used Tachos as a general so that he could retake Egypt.

Shortly afterwards Artaxerxes II died and Nectanebos II collected under the successor Artaxerxes III. an army of "more than a hundred thousand men" in Syria to crack down on speedometers. He therefore called on Tachos to “fight a battle for royal dignity” with him. Agesilaos, noticing Tacho's hesitation, advised him to take up the fight: "Not the one with the larger army wins, but the one who has more bravery". Tachos withdrew to a fortified city against the advice of Agesilaos. Nectanebo II lost many men in his first attack, which is why he built a wall and a moat around the city for tactical reasons. Tachos now feared for his safety. Agesilaos led a successful nightly sortie and defeated the following troops of Nectanebo II. Tachos, who kept the kingship, gave Agesilaos valuable gifts out of gratitude. Agesilaos died shortly afterwards on the way back home.

Plutarch (45 to 125 AD)

Plutarch reports that Tachos and Nectanebos II took part in the campaign together during the reign of Artaxerxes II. Agesilaus was disappointed that Tachos received the supreme command of the troops and is said to have characterized the Pharaoh overall as inflated and vain. Nectanebos II, whom Plutarch classified as the cousin of Tachos, fell away with his army because he had meanwhile been proclaimed the new pharaoh in Egypt. With the promise of valuable gifts, Nectanebo II was able to get Agesilaos to think about converting. Nectanebos II tried to win Chabrias on his side, but in vain. Agesilaus asked Sparta for further instructions. After Sparta gave Agesilaos a free hand, he united - allegedly in the interests of his hometown - with the troops of Nectanebo II.

Without the support of Nectanebo II's army, Tachos fled. Plutarch now also tells of an "army of one hundred thousand men", which however did not belong to Nectanebo II, but attacked him. The commander of this large force is said to have been a self-proclaimed Egyptian king from Mendes who rebelled against Nectanebo II. The latter - similar to Tachos with Diodorus - did not follow Agesilaus' advice to accept the challenge, but fled to a fortified city with the unwilling Spartan king. As with Diodorus, Agesilaus later made a successful sortie out of the city encircled by the enemy and won the day. So Nectanebo II was able to save his throne. He gave Agesilaos plenty of presents and rewarded him for participating in the war with an additional 230 talents in silver. Since winter had meanwhile arrived, Agesilaos drove his ships near land on the way home. He died near Libya at the age of 84 in the port of Menelaus.

Evaluation of the ancient sources

Xenophon's writing is the closest source to Tachos, but it is not a neutral vita of Agesilaos, but an enkomion . In his Hellenica , however, Xenophon devoted no space to the last years of Agesilaos. Diodorus based his statements presumably in a strongly abbreviated form on the 29-volume universal history of the 4th century BC. Living Greek historian Ephoros von Kyme , who incorporated his anti-Persian stance into his remarks. An analysis showed that Diodorus used the statements of Ephorus by Kyme repeatedly for his stories. Diodorus also seems to give the impression of giving objective and precise reports on the events of that time. Several examples show that this is not the case.

In the depictions of the dispute between Tachos and Nectanebos II, Diodorus deviates greatly from the parallel tradition, which reports in particular that Agesilaos switched from Tachos to Nectanebos II. Diodorus also apparently does not have a clearly defined definition of the term "Syria-Phenicia", since in other places he gives the cities of Joppa , Samaria and Gaza as "Syrian-Phoenician". Archaeological excavations exclude destruction due to military sieges in Phenicia for that period . It is therefore possible that Diodorus did not mean by “Syrian-Phoenician cities” the surrounding towns, but rather generally “Syrian-Phoenician fortresses” without any further localizations, which were the target of Egyptian attacks.

Diodor does not know anything about the chaos of the throne at the end of the reign of Artaxerxes II, as a result of which his son Ochos is said to have kept his father's death a secret for 10 months. He immediately lets Ochos follow Artaxerxes II. Since Diodorus announced the death of Artaxerxes II on 362/361 BC. Dated BC, there is an incorrect chronological classification of the campaign, which Diodorus with the subsequent "fight between Tachos and Nectanebos II." In the reigns of the two Persian great kings. In retrospect, Diodorus later reports in a confusing and contradicting manner, because on the one hand he had no knowledge of the military order against Tachos that Artaxerxes II gave his son Ochos and on the other hand the fighting of Ochos with events of the year 351 BC. Brought in connection.

Diodorus' claim that “Tachos went to Artaxerxes II via Arabia” to seek asylum there is incomprehensible and refers to sources of other historians who refer to Cambyses II who marched through “northern Arabia to Babylonia ". The normal route to the court of the Persian great king ran through the Phoenician territories of Straton. The flight of Tachos “via Arabia” does not seem logical, since the Pharaoh was near Sidon and would certainly have only chosen this detour if Straton had taken military action against Tachos with the Persian Prince Ochos. From a later source it is known that Straton broke the existing alliance with the Persians and rebelled together with Egypt against the Persian great king. The importance that Diodorus attached to the “route across Arabia” remains unclear. In the overall context of the other contradicting stories, however, his statement does not seem very convincing.

Particularly noticeable are the Greek mercenary troops that are always in action in connection with Egypt. Diodorus' glorification of Greek generals and mercenaries is striking. In his stories, they are repeatedly called upon on the front line of war for particularly difficult tasks, and their tactical advice is also asked for. Diodorus denies these qualities to the Persians and Egyptians, because they are the ones in need of Greek help. The statements by Diodorus are therefore very questionable overall, which is why a reliable historical confirmation of the details described cannot be made.

Location of speedometers

An exegete added in the Demotic Chronicle retroactively as oracle statement formulated prophecy , which said that a Pharaoh of Egypt in the region Syria- Palestine draws. In his absence an “exchange of the pharaohs” follows: the one who goes to the land of choir will be given in exchange for the one who will be in Egypt . Whether this “prediction” actually referred to the removal of speedometers cannot be said with certainty, as Nectanebo II also fled from Egypt to another country at the end of his reign.

The whereabouts of speedometers and his death have not yet been clarified. Due to the usurpation supported by Agesilaus, the Pharaoh probably fled to the Phoenician prince Straton of Sidon . Possibly Tachos then asked Artaxerxes II for asylum . After the Persian great king died a little later, his son Ochos followed as Artaxerxes III. on the throne. An autobiography of the Egyptian priest Wennefer indicates that he was involved in the campaign against the Persians in Phenicia. Wennefer reports that he was initially suspected of treason and later rehabilitated on the false accusations . As the inscription has only survived in part, the connections cannot be interpreted with certainty by the Egyptologists.

For example, it remains unclear whether Wennefer together with Tachos to Artaxerxes II. Or only later to Artaxerxes III. got. After his visit Wennefer returned to Egypt from the Persian great king. The reasons why Wennefer traveled to the Persian royal court in his function as "head of the summoners of the serket " could also not be clearly identified. The mummy or the remains of Tacho's corpse have not yet been discovered, nor have his grave or sarcophagus .

literature

General

- Dieter Arnold: Temples of the Last Pharaoh . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1999, ISBN 0-19-512633-5 , pp. 122-124.

- Pierre Briant : Histoire de l'Empire Perse: De Cyrus á Alexandre . Fayard, Paris 1998, ISBN 2-213-59667-0 (English translation: Peter T. Daniels : From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire . Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake 2002, ISBN 1-57506-031-0 ).

- Leo Depuydt : Saite and Persian Egypt, 664 BC-332 BC (Dyns. 26-31, Psammetichus I to Alexander's Conquest of Egypt). In: Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, David A. Warburton (eds.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology (= Handbook of Oriental studies. Section One. The Near and Middle East. Volume 83). Brill, Leiden / Boston 2006, ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5 , pp. 265-283 ( online ).

- Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 0-500-05128-3 , pp. 256-257 ( PDF file; 67.9 MB ); retrieved from the Internet Archive .

- Werner Huss : Egypt in the Hellenistic Period: 332-30 BC Chr.Beck , Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-47154-4 .

- Friedrich Karl Kienitz : The political history of Egypt from the 7th to the 4th century before the turn of the times . Akademie, Berlin 1953, pp. 212-213.

- Alan B. Lloyd: The Late Period (664-332 BC) . In: Ian Shaw: The Oxford history of ancient Egypt . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-19-280293-3 , pp. 369-394.

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , p. 281.

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Handbook of the Egyptian king names . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-422-00832-2 .

Demotic Chronicle and Dating

- Heinz Felber : The demotic chronicle . In: Andreas Blasius: Apokalyptik und Egypt: A critical analysis of the relevant texts from Greco-Roman Egypt (series: Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta, No. 107) . Peeters, Leuven 2002, ISBN 90-429-1113-1 , pp. 65-112.

- Friedhelm Hoffmann , Joachim Friedrich Quack : Anthology of demotic literature (= introductions and source texts for Egyptology, Vol. 4 ). Lit, Berlin 2007, ISBN 3-8258-0762-2 .

- Werner Huss: The Macedonian King and the Egyptian Priests: Studies on the History of Ptolemy Egypt . Steiner, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-515-06502-4 .

- Wilhelm Spiegelberg : The so-called demotic chronicle of Pap. 215 of the Bibliothèque nationale zu Paris along with texts on the back of the papyrus (= Demotic Studies, Vol. 7 ). Leipzig 1914.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Term of office: 2 years.

- ↑ In the demotic chronicle three years are indirectly mentioned as co-reign, since 16 years are mentioned for Nectanebo I , to which three years were added; Dating of the Egyptologists: Nectanebo I from 378 to 360 BC BC, Nectanebo II from 359 to 341 BC According to Madeleine DellaMonica: Les derniers pharaons: Les turbulents Ptolémées, d'Alexandre le Grand à Cléopâtre la Grande. Les temples ptolémaïques . Maisonneuve et Larose, Paris 1998, ISBN 2-7068-1272-9 , p. 6 and Miriam Lichtheim : Ancient Egyptian Literature: A book of readings. Vol. 3: The late period . University of California Press, Berkeley 2006, ISBN 0-520-24844-9 , p. 41; Speedometers from 361 to 359 BC According to Peter T. Daniels: From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire . P. 663; Speedometers from 361/360 to 359/358 BC B.C. by Dieter Arnold and Jona Lendering, among others . As a further indication, the dating of the 16th year of the reign of Nectanebo II for the year 343 BC. The first year of the reign of Nectanebo II began around 359/358 BC. Chr .; according to Friedhelm Hoffmann, Joachim Friedrich Quack: Anthology of demotic literature . 162 and John Ray: The Reflections of Osiris: Lives from ancient Egypt (The Magician Pharaoh Nectanebo II, reigned 359 / 358-343 / 342 BC) . University Press, Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-19-515871-7 , p. 127; Thomas Schneider, Werner Huss and Jürgen v. Beckerath, on the other hand, set tachometers for the reign of 362 to 360 BC. Chr.

- ↑ a b c Werner Huss: Egypt in the Hellenistic Period: 332-30 BC Chr. P. 48.

- ↑ a b Felix Scheidweiler : To the Platonic Phaedrus . In: Hermes 83, No. 1 . Franz-Steiner 1955, p. 120.

- ^ Alfred Wiedemann: Egyptian history . Friedrich Andreas Perthes, Gotha 1888, p. 291.

- ↑ Friedhelm Hoffmann, Joachim Friedrich Quack: Anthology of demotic literature . P. 164.

- ↑ a b Thomas Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs . P. 281.

- ↑ digitalegypt: speedometer fragment (shell from Memphis) .

- ^ William Gillian Waddell: Manetho (The Loeb classical Library 350) . Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.) 2004 (Reprint), ISBN 0-674-99385-3 , pp. 183-185.

- ↑ a b Friedhelm Hoffmann, Joachim Friedrich Quack: Anthology of demotic literature . P. 185.

- ↑ Werner Huss: The enigmatic Pharaoh Chababasch . In: Studi epigraphici e linguistici sul Vicino Oriente antico (SEL) 11 . 1994, p. 104.

- ↑ Werner Huss: Egypt in the Hellenistic Period: 332-30 BC Chr. P. 46.

- ↑ Aidan Dodson: Monarchs of the Nile . Rubicon, London 1995, ISBN 0-948695-20-X , p. 200.

- ^ Thomas Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs . P. 176.

- ^ Klaus Peter Kuhlmann: Ptolemais - Queen of Nectanebo I - Notes on the Inscription of an Unknown Princess of the XXXth Dynasty . In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute (MDAIK) 37 . Cairo 1981, p. 267.

- ↑ The full moon night from the 21st to the 22nd Pharmouthi , the fourth month of the Peret season according to Friedhelm Hoffmann, Joachim Friedrich Quack: Anthologie der demotischen Literatur . P. 162; Jean Meeus : Astronomical Algorithms (Applications for Ephemeris Tool 4,5) . Barth, Leipzig 2000 for: Ephemeris Tool, Version 4.5 (conversion program 2001) .

- ↑ a b Heinz Felber: The demotic chronicle . P. 82.

- ↑ Heinz Felber: The demotic chronicle . P. 91.

- ↑ Werner Huss: Egypt in the Hellenistic Period: 332-30 BC Chr. P. 48 and Xenophon, Cyropaedia , book 8,8 .

- ↑ Ernst Gölitzer: formation and development of the Alexandrian coinage 30 v. Until the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty . Akademie, Berlin 2004, ISBN 978-3-05-004089-9 , p. 6.

- ↑ Eduard Meyer : History of antiquity: The Persian Empire and the Greeks. The battle of Mantinea and its consequences. Epaminondas' position in history . Cotta, Stuttgart 1969, p. 459 and footnote 835.

- ^ Jona Lendering: Teos In: Livius .

- ↑ Friedhelm Hoffmann, Joachim Friedrich Quack: Anthology of demotic literature . Pp. 184 and 189.

- ↑ Peter T. Daniels: From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire . P. 663.

- ↑ Date based on the Julian calendar.

- ↑ Peter T. Daniels: From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire . P. 669.

- ↑ Diodor, Bibliothéke historiké 15.92.2 .

- ↑ a b c Peter T. Daniels: From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire . Pp. 784-785.

- ^ Alan B. Lloyd: The Late Period (664-332 BC) . P. 389.

- ^ Alan B. Lloyd: The Late Period (664-332 BC) . P. 390.

- ↑ a b c Peter T. Daniels: From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire . P. 665.

- ^ Georgios Synkellos , Ekloge chronographias 1486, 20ff.

- ↑ Xenophon, Agesilaos 2, 28-31; Diodor, Bibliothéke historiké 15, 92f .; Plutarch, Agesilaus 36-40; Cornelius Nepos, Agesilaus 8.

- ↑ a b Xenophon, Agesilaos II .

- ↑ Cornelius Nepos: Agesilaus , 8.2–8.7 .

- ↑ Diodor, Bibliothéke historiké Chapter 15.92

- ↑ Artaxerxes III. can officially take the throne at the earliest December 359 BC based on the information in the Babylonian tablets. And no later than April 358 BC Have climbed. From the sixth year of reign of Artaxerxes III. is for November 22nd, 353 BC. A lunar eclipse , which is why his first year of reign was not before December 359 BC. May have started. Jona Lendering dates to February / March 358 BC. Chr.

- ↑ Diodor, Bibliothéke historiké Chapter 15.93

- ↑ Plutarch, Agesilaus, Chapter 37 .

- ↑ Plutarch, Agesilaus, Chapter 38 .

- ↑ Plutarch, Agesilaus, Chapter 39 and Chapter 40 .

- ↑ Julius Friedrich Wurm, editor of a German translation by Diodorus in the first half of the 19th century, suspects that Diodorus confused Tachos with Nectanebo II and the latter with the new Egyptian pretender from Mendes.

- ^ A b Peter T. Daniels: From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire . Pp. 665 and 674-675.

- ↑ Carsten Binder: Plutarch's Vita des Artaxerxes. A historical comment . de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-020269-4 . P. 359.

- ↑ Peter T. Daniels: From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire . P. 994.

- ^ John Ray: The Reflections of Osiris: Lives from Ancient Egypt (The Magician Pharaoh Nectanebo II, reigned 359 / 358-343 / 342 BC) . University Press, Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-19-515871-7 , p. 117.

- ↑ Werner Huss : Egyptian collaborators in Persian times. In: Tyche. Contributions to ancient history, papyrology and epigraphy . Volume 12, 1997, pp. 131-143, here p. 139.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Nectanebo I. |

Pharaoh of Egypt 360 to 359 BC Chr. |

Nectanebo II |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Speedometers |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Teos; Taos; Djedhor; Djedho |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Pharaoh of the 30th Dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 5th century BC BC or 4th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 360 BC Chr. |