Aegyptiaca (Manetho)

" Aegyptiaca " ( ancient Greek Αἰγυπτιακά ) is the usual Latin title of a chronicle written by Manetho on ancient Egyptian politics, religion and history. The author Manetho was probably a priest from Sebennytos in Lower Egypt , who was probably under the pharaohs Ptolemy I , Ptolemy II and Ptolemy III. lived. Georgios Synkellos set Manethos work at the same time or a little later than Berossus in the reign of Ptolemy II (285–246 BC), under which he is said to have written the Egyptian . Manetho's motives may be based on the one hand in the Ptolemaic ignorance of the ancient Egyptian language and on the other hand in the refutation of Herodotus accounts of ancient Egyptian history .

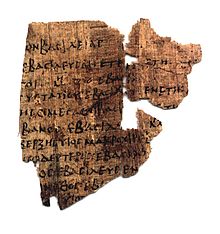

The Aegyptiaca originally consisted of three books that were partially copied and translated by late ancient scholars and historians . The lack of the original Manethos writings prompted Egyptology , among others, to critically examine the available copies, since without a precise analysis a wrong picture of the actual content emerges. With this due caution in mind, Manetho's reports are viewed as the cornerstone of ancient Egyptian history, as Manetho divided the continuous succession of rulers into 30 dynasty sections, which form the chronological framework in Egyptology.

backgrounds

The transcripts

Since Manetho's works have been lost at an early stage, the question arises as to which parts of the Manethonic registers that are based on the traditional version of an unknown author from the first century BC. Are based on historical data. The excerpts ( epitoms ), names of rulers and fragments taken over in this way were taken into account in the works of the historians Flavius Josephus , Iulius Africanus and Eusebius , although larger passages of the records are undoubtedly not from Manetho himself. In the eighth century AD, Georgios Synkellos translated some of the surviving “copies of the copies”. In addition to Eusebius' fragments, there is also an Armenian translation, which, however, also contains further freely invented statements. Epitoms of the history of Manetho were written at an earlier point in time - but not by Manetho himself, even if there are conceivable reasons for this assumption in the form of lists of the dynasties and the outstanding kings or special events.

The main concern of Jewish historians, such as Flavius Josephus, and Christian chroniclers was to harmonize the content of the Bible with ancient Egyptian history in order to obtain "historical evidence" regarding the authenticity of the Old Testament . The epitoms handed down in manethonically were therefore a welcome basis for adding or falsifying statements. For example, the Aegyptiaca report in great detail about the reign of terror of the Hyksos . Biblical attempts at comparison are particularly evident in the narration of the story of Moses . But other legendary tales seem to have the authors interested in, such as the legend of Pharaoh Bocchoris who by his successor or anti-king Shabaka said to have been burned alive. The omission of certain historical events, on the other hand, can actually only be proven in the Book of Sothis .

The founder of Christian chronology, Julius Africanus, whose work Historiae (Greek Κεστοί) was written shortly after AD 221, passed on the epitomes in a more accurate form, while Eusebius, whose work dates from around AD 325, is responsible for major unauthorized changes to the original template. Even from the conclusive explanation of the transmissions of Manetho's texts, it can be seen that many problems persist and that it is extremely difficult to be certain of what is truly Manethonic and what is spurious or incomplete.

So if Manetho (Josephus) , Manetho (Africanus) or Manetho (Eusebius) is used in Egyptology today , then the second name in brackets refers to the author of the actual statement made by the Egyptian priest Manetho.

Possible sources

In connection with Manetho's statements, which are of great interest to Egyptologists and historians, the question remains where Manetho got his information from. The deified and mystified prehistory, which he partly devised and wrote, can be traced back to political-religious worldviews typical of Manetho's epoch.

However, it becomes difficult in the case of the so-called king list. Manetho knows in his stories to tell of very special incidents with certain kings, which, if they are based on truths, it becomes clear that it is detailed knowledge to which simple scribes and officials had no access. Manetho obviously had invaluable advantages in writing an excellent history of Egypt. He must have had access to every imaginable record - papyri from the temple - archives , hieroglyphic tablets, wall sculptures and countless relief inscriptions . In ancient Egypt only high priests had access to these records and this fact therefore leads to the conclusion that Manetho was such a high priest . Overall, the work seems to be completely in the tradition of ancient Egyptian annals , which list events without analyzing them further critically. Several times the suspicion arises that popular narratives, without great historical value, have also flowed into the representations.

The three books of Manethos

The structure of the “ king lists ” is always the same in terms of structure and syntax: Each dynasty is introduced with the name of the new royal house, followed by the name and period of reign of each ruler. This is followed by an anecdote for some rulers, for example Necherophes , about a special event that is said to have taken place under the respective king. Some dynasties did not list their names and instead summarized the entire dynasty in one sentence. The names of the kings are reproduced in a strongly Graecized manner and are therefore often difficult to assign.

Book 1 (era of gods and spirits of the dead as well as kings up to the 11th dynasty)

In the first book, Manetho first describes the time of the gods and spirits of the dead. To do this, he used the Greek equivalents of the ancient Egyptian gods. In particular, Manetho made use of ancient Egyptian mythology that only emerged in the course of ancient Egyptian history. Manetho showed particular interest, on the one hand, in the mystical- divine early history and, on the other hand, in the “ heroic adventures” of Osiris and Horus .

“The first (God) in Egypt was Hephaestus ( Ptah ), who revealed fire to the Egyptians. His was Helios ( Re ). After him was Agathodaimon ( Shu ). After him was Kronos ( Geb ). After him was Osiris and then Typhon ( Seth ), brother of Osiris. After him was Orus (Horus), son of Osiris and Isis . They first ruled over the Egyptians. After them the monarchy continued to Bidis (Wadjnadj) for 13,900 years. According to these gods, the descendants of the gods ruled for 1,255 years, and so did other kings for 1,817 years. After them 30 kings followed from Memphis for 1,790 years . After these then other (kings) of This for 350 years . And then the reign of the spirits of the dead and their descendants (followed) for 5,813 years. "

This is followed by the much-cited list of kings, which is so important and much-cited for Egyptologists and historians, which unanimously begins with a king named " Menes " in the copied versions of all ancient authors . In the first book, Manetho reports on the period from the royal 1st to the 11th dynasty and tries to include all rulers of Egypt. Manetho dated the “ Souphis pyramid ” as the “great pyramid ” 4,300 years before Cambyses (529-522 BC) in the reign of Cheops ( 4th dynasty ).

The kings were assigned very well for the Old Kingdom . What is striking, however, are the sometimes serious differences in the respective copies of the information about the reigns of certain kings. Eusebius, for example, attributes 42 years to King “Uenephes”, while the version by Africanus speaks of 23 years. With the first interim period , a time of turmoil began which made Manetho difficult and confronted him with great chronological problems. So he owes a clear assignment of the rulers due to the only fragmentary sources available to him. The Middle Kingdom finally showed a calming and new stability that led Manetho to assume a coherence of the royal line.

The version by Africanus names "130 kings with a total reign of 2,261 years" for the first eleven dynasties; an additional 70 kings were given for the 7th dynasty , but the associated total length of government of 70 days is only to be understood symbolically as an interregnum , which makes the uncertainties with regard to the king assignments recognizable. Also striking are those details from Africanus that deviate from the individual dynasty dates actually mentioned. For example, for the 5th dynasty, “the eight kings from Elephantine of this dynasty” are mentioned in the introductory remark ; the list of the 5th dynasty, on the other hand, lists nine kings who have a total reign of 218 years. The total 248 years reported in the final remark for the 5th dynasty include the 30 years of reign of King “ Othoes ” of the 6th dynasty , which are then counted again with him as the “founder of the 6th dynasty from Memphis ”.

Book 2 (Kings from the 12th to the 19th Dynasty)

In the second book, Manetho reports on the kings of the 12th to 19th dynasties . He describes the phase following the 11th dynasty as "strengthening stability". King Amenemhet III ("Lamares / Lampares") is said to have built his grave as a " labyrinth in the arsenoitic district " on Lake Moeris . Whether Manetho relied on the mentions of Herodotus remains unclear, since Herodotus made a connection to a king "Moeris" as the founder of the labyrinth in this context.

With the decline of the Middle Kingdom, the confusing Second Intermediate Period followed , which again presented Manetho with the problem of assigning the kings to the respective dynasties. For these reasons, the names of rulers of dynasties 13 , 14 , 16 and 17 , to whom he assigns a total of only a total of reigning years , is probably not mentioned . The 15th dynasty of the “great Hyksos ” is listed in the Manethonic versions either as 15th or 17th dynasty, evidence of the confusing sources of that era. In particular, the accompanying explanations on the Hyksos show an increase in Greek , Jewish and Christian post-processing of the Manethonic versions, which is why historians have great difficulty in filtering out the actual statements of Manethos.

The 18th Dynasty marks the beginning of the New Kingdom era . Due to the end of the Hyksos occupation of Egypt, Manetho returns to a clear and stable structure of the king list. For the period from the 12th to the 19th dynasty, the three Manethonic versions with “2,121 years” show another correspondence, whereby Africanus with “96 kings” has four rulers more than the stated “92 kings” by Eusebius or the Armenian Version.

Book 3

Kings from the 20th to the 31st dynasty

The third book reports from the 20th to the 31st dynasty . The third interim period beginning with the 21st dynasty (1070–664 BC) apparently presented Manetho with new assignment problems , since he confused Petubastis I ("Petoubates") as the " founder of the Tanitic 23rd dynasty " with Petubastis II : " During the reign of" Petoubates "the first Olympiad took place " (776-773 BC). Petubastis II is not mentioned in any king list.

According to Manetho, “Petoubates” was followed by the pharaoh “ Osochor / Osorthon, (whom) the Egyptians called Heracles ”. This sentence led to controversial discussions in Egyptology regarding the king behind it. Jürgen von Beckerath suspects Osorkon IV to be behind "Herakles", but this contradicts the dating of Petubastis I. Scheschonq IV. Is being considered as another possible king , since in the Manethonian version Osorkon III as the third king of the 23rd dynasty . ("Psammous / Phramus") followed.

The end of the 25th dynasty , which included Nubian rulers from Napata , ushered in the transition to the late period (664–332 BC). With the String Dynasty following the 25th Dynasty , Egypt experienced a renaissance of ancient Egyptian traditions, which came to a sudden end with the Persian conquest ( 27th Dynasty ). The pharaohs of Dynasties 28 , 29 and 30 were able to free themselves from Persian rule for about 60 years (404–342 BC), before the 31st dynasty briefly from 342–332 BC. BC Egypt ruled for ten years after another successful Persian invasion.

Completion of the third book

It is not completely clear whether Manetho or an anonymous author wrote the 31st dynasty in the third book, since the Armenian historian Moses von Chorene reports that " Manetho called Nechtanebos the last king of the Egyptians ". Hieronymus reports similarly the historian Eusebius, whose third book closes after “Nectanebos”. In the Manethonic Africanus version and the Armenian version, however, Manetho's notes end with the death of Darius III. : “ Dareios, whom Alexander of Macedonia killed. End of the third book by Manetho ”. Georgios Synkellos commented on the third book by Africanus: " Manetho wrote a list of 31 dynasties up to the time of Nektanebo and Ochus ". The identical structure of the three books suggests a division into 31 dynasties by Manetho.

The Macedonian- Ptolemaic 32nd dynasty, founded by Alexander, also followed the 31st dynasty and continued to exist until Manetho's death. A year for the period in the third book is missing in Eusebius and in the Armenian version. The duration of 1,050 years mentioned by Africanus is wrong; if you add up his years of government, the result is only 850 years. Since a year is only available in the Africanus version, the corresponding information was probably added by Greek scribes.

Georgios Synkellos and different information

The statements made in the Manethonic versions with regard to the number of kings and their reigns contradict each other just as often as the comments of Georgios Synkellos, who, for example, corrected Manetho's notes regarding the years:

“The 113 generations in these three books, divided into 30 dynasties, make a total of 3,555 years, starting with the year 1586 Annus Mundi (3924 BC) and ending with the year 5147 Annus Mundi (363 BC) , 15 years before Alexander conquered the world. "

Modern research and reception

As already noted, the Aegyptiaca , or their preserved fragments, are of great importance for the reconstruction and understanding of the past of Egypt, as they offer a certain guide with which the chronology of Egypt can be divided into dynasties. Although the understanding of dynasty may be different today, Manetho has created a cornerstone for a meaningful division of time with his work. Nevertheless, certain problems and contradictions remain:

Such a contradiction in the content of Manetho's history is the fact that it was actually not part of Egyptian traditions and customs to write history. It was a peculiarity of Greek culture. The Egyptians limited their "chronicles" to dedications and inscriptions that were addressed to the king (Pharaoh) or a deity. The creation of a time and action framework for the purpose of recording and shaping a history, as Manetho did, reveals that he was orienting himself on Greek instead of Egyptian models when he wrote the Egyptiaca , although he had certainly noticed the cultural and traditional contradiction. Therefore, the question rightly arises how much untruth had already flowed into Manetho's original work.

Another disadvantage, especially in the transcripts of later historians, is that they are shaped and influenced by post-Christian theologies and world views. Modern Egyptologists continue to divide Manethos into dynasties, but view the anecdotes about individual rulers with skepticism . Toby AH Wilkinson writes: The lists of Herodotus and Manethus were finally written down two and a half thousand years later after the events of the Early Dynasties. At such a distance, accuracy can no longer be expected. As with all “histories”, the material presented reflects the views of the chronicler's epoch. And further: However, the royal names given by Manetho are permanently difficult to equate with the recorded names of the early dynastic sources. Moreover, some of the more fantastic details about individual kings appear to have come from the realm of mythology and cannot be considered historically accurate.

The story about the early king "Kaiechos" (Latin Cechus ), who is identified with Nebre , is a vivid example . Manetho reports that under him certain animals were elevated to gods. Eberhard Otto notes on this: Manetho's message that Apis, Mnevis and the goat of Mendes were declared gods under King Kaiechos (2nd dynasty) can perhaps be explained by the fact that the name of this king in the late period was called “the bull of the Bulls ”(Kakau) was understood. That the cult is actually older is shown especially for Apis by the appearance of his picture on an ostracon with an artist's drawing from a grave of the 1st Dynasty in Saqqara , but also the consideration that at a time when the Egyptians already had the anthropomorphic idea of gods was common, an animal cult could not possibly have been newly introduced. Rather, all animal cults, whether we can trace them so far or not, provided they do not go back to later cult transmissions (such as the veneration of Apis in various serapes), belong to one and the same religious-historical development stage that we are no longer able to grasp historically. The tradition of Manethos, which others contradict by the way, can say for us nothing more than that the origin of the animal cult was postponed to the almost legendary rulers of the first historical period .

On the other hand, there are reports that might actually be based on true events. Manetho reports about King Hetepsechemui , whom he calls "Boethos", that under him a chasm opened up at Bubastis and many died . This description could indicate a severe earthquake , as the region around Tanis - today's Tell el-Farain - lies in a seismologically active zone. In general, the aegyptiaca will continue to be the subject of intensive research in the future.

historiography

|

Manetho Aegyptiaca (Three Books) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Text changes by pro and anti-Jewish writers as well as by Jewish historians |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Flavius Josephus " Contra Apionem " (1st century AD) |

Epitoms with dynasties, supplemented with additional information without reference to Manetho |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eusebius of Caesarea Chronicae (fourth century AD) Narrated by Hieronymus |

Book of Sothis (Third Century AD) |

Sextus Iulius Africanus Historiae (Third Century AD) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Armenian version of Eusebius (sixth to eighth centuries AD) |

Eratosthenes version | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chronicle of ancient Egyptian kings according to Josephus |

Papyrus Baden 4.59 (fifth century AD) |

||||||||||||||||||||

literature

- Wolfgang Helck : Investigations into Manetho and the Egyptian King Lists (= Investigations into the history and antiquity of Egypt. Vol. 18 ). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1956.

- Felix Jacoby : The fragments of the Greek historians (FGrHist): history of cities and peoples (horography and ethnography), C: authors about individual countries, No. 608a - 856 (1, Egypt - Geten, No. 608a - 708) . Brill, Leiden 1958, FGrHist no. 609, pp. 5-112.

- Felix Jacoby: The Fragments of the Greek Historians (FGrHist III C1, No. 609). Greek texts with German-English comments. CD version . Brill, Leiden 2005, ISBN 90-04-14137-5 .

- Josef Karst: The Chronicle. Translated from Armenian. With text-critical commentary (German translation) . Hinrichs, Leipzig 1911.

- Eberhard Otto : Contributions to the history of bull cults in Egypt (= studies on the history and antiquity of Egypt. Volume 13 ) Hinrichs, Leipzig 1938; Reprint: Olms, Hildesheim 1964.

- Dagmar Labow: Flavius Josephus “Contra Apionem”, Book I: Introduction, text, text-critical apparatus, translation and commentary. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-17-018791-0 .

- Folker Siegert: Flavius Josephus: About the originality of Judaism (Contra Apionem). With contributions by Jan Dochhorn and Manuel Vogel (= writings of the Institutum Judaicum Delitzschianum ). German translation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 3-525-54206-2 .

- Alden A. Mosshammer: Ecloga Chronographica: Georgius Syncellus. (= Bibliotheca Scriptorum Graecorum et Romanorum Teubneriana ). Teubner, Leipzig 1984

- Carolus Müller: Fragmenta historicorum Graecorum. 5 volumes (reprint of the Paris 1938 editions). Minerva, Frankfurt a. M. 1975.

- Gerald P. Verbrugghe, John M. Wickersham: Berossos and Manetho, introduced and translated. Native traditions in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor (Michigan) 2000, ISBN 0-472-08687-1 .

- William Gillian Waddell: Manetho (= The Loeb classical Library. Vol. 350 ). Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.) 2004 (Reprint), ISBN 0-674-99385-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Folker Siegert: Flavius Josephus: About the originality of Judaism (Contra Apionem) . P. 34.

- ^ Waddell flat share: Manetho. The Loeb classical library . S. xiv-xxi.

- ↑ Naguib Kanawati: Conspiracies in the Egyptian Palace: Unis to Pepy I . London 2002, ISBN 0-415-27107-X , pp. 11-12.

- ↑ a b Gerald P. Verbrugghe, John M. Wickersham: Berossos and Manetho . P. 99.

- ↑ Gerald P. Verbrugghe, John M. Wickersham: Berossos and Manetho. Pp. 130-131.

- ↑ Gerald P. Verbrugghe, John M. Wickersham: Berossos and Manetho . Pp. 101 and 134.

- ^ William Gillian Waddell: Manetho. Pp. 51, 53, 57, 63-65.

- ↑ In the Armenian version, the term "labyrinth" was not used, but rather: the cave spiral-shaped ; according to translation Karst.

- ↑ Gerald P. Verbrugghe, John M. Wickersham: Berossos and Manetho . P. 138.

- ↑ Folker Siegert: Flavius Josephus: About the originality of Judaism (Contra Apionem). P. 113.

- ↑ Gerald P. Verbrugghe, John M. Wickersham: Berossos and Manetho. P. 143.

- ↑ Jürgen von Beckerath: Osorkon IV. = Herakles. In: Göttinger Miszellen, No. 139. University of the City of Göttingen, Seminar for Egyptology and Coptic Studies, Göttingen 1994, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Gerald P. Verbrugghe, John M. Wickersham: Berossos and Manetho. P. 201.

- ^ A b c Gerald P. Verbrugghe, John M. Wickersham: Berossos and Manetho . P. 152.

- ^ Armenian version based on Gerald P. Verbrugghe, John M. Wickersham: Berossos and Manetho . P. 152.

- ^ A b William Gillian Waddell: Manetho (The Loeb classical Library 350) . Pp. 184-185.

- ↑ a b Gerald P. Verbrugghe, John M. Wickersham: Berossos and Manetho . P. 100.

- ↑ Folker Siegert: Flavius Josephus: About the originality of Judaism (Contra Apionem). Pp. 41-42.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt , p. 64.

- ↑ Eberhard Otto: Contributions to the history of the bull cults in Egypt (dissertation) . P. 5.

- ^ William Gillian Waddell: Manetho. (= The Loeb classical Library. Vol. 350). P. 35.