Temple of Ptah (Memphis)

| Temple of Ptah in hieroglyphics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hut-ka-Ptah Ḥwt-k3-Ptḥ House of the Ka des Ptah |

||||||

| Ruins of the hypostyle hall and pylons of Ramses II. | ||||||

The temple of Ptah in Memphis ( Egyptian Hat-ka-Ptah ) is one of the oldest and most important temples of ancient Egypt . It is located west of the Nile in Memphis , the former capital of the country, near the modern village of Mit Rahina . The temple was dedicated to the creator god Ptah , the main god in Memphis, who together with Sachmet and Nefertem formed a divine triad .

The Egyptian sanctuary has long been the scene of historical events. Not only were coronation ceremonies and Sedfests celebrated, but also triumphal procession, seizures of power, conquests and looting took place here.

Today's temple area is a field overbuilt with modern settlements and littered with ruins, on which there are only individual ancient stone blocks and remains of statues. The poor state of preservation is mainly due to the nearby city of Cairo , as many temple stones were used to build the medieval city.

Archaeological excavations have so far proved difficult because much of the area due to the high water table is under water.

Name and location

Map of Egypt |

The Egyptian name of the temple ḥwt k3 Ptḥ (translated: "House of the Ka des Ptah"), pronounced Haut-ka-Pitah or He-ko-Ptah, probably gave the country its ancient Greek name Aigyptus .

The name ḥwt-nṯr nt Ptḥ rsj jnb = f ("Temple of Ptah, south of its wall"), which probably indicates its original location south of Memphis ( jnb (w) ḥḏ = "White Wall (s)"), has been handed down . This contradicts Herodotus' report that the temple was founded within the city. As excavations by the archaeologist Jaromír Málek have shown, the settlement jnb (w) ḥḏ was much further north, near the modern village of Abusir, in the early Dynastic and Old Kingdom times . An early Ptah sanctuary could be located a little to the west of the current enclosing walls in Kom el-Fachri - the city and temple were initially spatially separated from one another. Only towards the end of the Old Kingdom did the settlement shift further south and together with the sanctuary formed the capital "Men-nefer".

Building history

According to Herodotus , the founding of the temple goes back to Menes , who is said to have founded the city of Memphis. Little is known about the early construction phases; the first traces come from the Middle Kingdom . Individual blocks scattered throughout the temple area testify to building activities by Amenemhet I , Amenemhet II , and Sesostris III. and Amenemhet III.

Only a single Ptah temple is said to have existed from the Old Kingdom to the middle of the 18th Dynasty . It was not until Thutmose IV. Began to found another temple in Kom el-Fachri . Amenhotep III have to be in the range built another temple of Ptah, who as a million years house functioned and was later demolished.

The most important construction phase is Ramesside and ranges from Seti I to Ramses II to Ramses VI. Most of the new buildings and extensions come from Ramses II. Among other things, he built the west hall, the forecourt with pylon north of the main temple and renewed the sanctuary. He also put up several colossal statues. During this time, the facility must have been similar in size to today.

During the strings time it came to the construction of porticos and lobbies. According to Herodotus, Psammetich I. is said to have carried out extensive construction work. The southern forecourt supposedly came from him, which was confirmed by Malek. The Apis complex ascribed to Psammetich was not created until later. During the 26th dynasty , a first wall was probably built, which should have been very similar to the later one from the Greco-Roman period.

Nectanebo I and Nectanebo II added some gates and pylons during the 30th Dynasty .

The wall and the granite gate of Ptolemy IV on the east wall come from Greco-Roman times .

description

The temple area was enclosed by a trapezoidal brick wall, which had the dimensions 410 × 580 × 480 × 630 meters and was built in Ptolemaic or Roman times. Main gates were let in in all four directions, through which two intersecting main axes ran. The building of the main temple, from which only the western entrance could be proven, was aligned along the east-west axis.

West Hall of Ramses II.

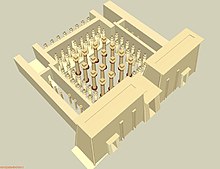

From the main temple, only a few remains of the western entrance hall of Ramses II are visible today, which were first excavated by Auguste Mariette in 1871 . The entrance was a 74-meter- wide stone pylon that was integrated into the surrounding wall. In front of it stood three or four colossi of the king. The pylon had three entrances, with the central entrance supported by quartzite posts . While the side entrances led into side corridors, the middle gate leads to a hypostyle with 4 × 4 papyrus columns, which are surrounded on all sides by a double row of lower columns and were 13 meters high .

Behind it follows a temple part with a column front. The main part of the temple has completely disappeared. A gate made of red granite from Ptolemy IV can only be found in the eastern enclosure wall. Ramses II had a forecourt with a pylon added to the north of the main temple.

It is noteworthy that many older spoils were built into the walls and foundations . The posts and lintels of Niuserre ’s solar sanctuary were found near Abusir. A lintel of Teti II from Saqqara and reliefs from a mastaba could also be recovered. In addition, steles from the time of Thutmose I to the 19th dynasty , over 160 fragments of Ramessid relief stones, columns and colossal statues as well as a Talatat block were discovered.

According to Gerhard Haeny , the design of the west hall is a basilica complex of the late 18th dynasty.

Apis temple and embalming house

Herodotus reports from an Apis temple ("Palace of the living Apis", ancient Greek Άπιείον ), which was built in the 26th dynasty and was located in the southwest district of the temple area. The exact location and date are unknown. The temple was the site of the Apis cult and housed a living sacred Apis bull. After his death, the high priests of Ptah replaced him with a newly chosen animal. It is said by ancient writers that the bulls gave oracles here and that Apis's birthday was regularly celebrated.

The center of the temple was occupied by a courtyard in which the bull could run freely. The courtyard was surrounded by halls and six meter high statue pillars . A cult building for the Isis cow was added to the sanctuary , as Isis was considered the mother of Apis. Strabon reports:

“In front of the sanctuary is a courtyard in which there is still a sanctuary that belongs to the mother of Apis. In this courtyard, Apis is released at a set hour, especially to show him to strangers; because although you can watch him through a window in the temple, people want to see him outside too. But when he has made a short round of jumps in the yard, they bring him back to the familiar stable. "

The temple house was endowed with rich foundations in the Ptolemaic period.

A little to the south, during an Egyptian excavation between 1940 and 1942, an embalming house for the Apis bull was uncovered. It was a simple brick building with parallel, elongated rooms that are reminiscent of warehouse buildings. The building dates from the time of Nectanebo II, but an earlier building must have existed. An embalming table was donated by Scheschonq I. Shabaka and Amasis built small chapels.

The embalming tables, which are over five meters long, are made of calcite . On the long sides there are lion beds worked as a relief. Containers at the foot end were used to collect fluids (body fluids) from the dead bulls.

A processional street lined with sphinxes , chapels and monuments led from the embalming house to the Serapeum in Saqqara, where the bull mummies were transferred. The road and the bull's tombs were uncovered by Mariette in 1850.

Remaining temple district

At the north gate, fragments of statues and a reused quartzite architrave of Amenemhet III. found. The interior of the area housed other statues, including a group statue of Ramses II with Ptah, which is now in Copenhagen . Furthermore, a sphinx of the king (now in Philadelphia ) and a seated statue of Amenophis, son of Hapu ( Oxford ) were recovered. An inscription on the statue tells of the construction of another Ptah temple by Amenhotep III. west of the main temple. The building was named "Nebmaatre, united with Ptah" and was a million year house in which the king was worshiped as a living manifestation of Ptah. The temple was demolished by Ramses II and replaced by a new building.

Several colossal statues of Ramses II were once placed in front of the south entrance. One of the statues stood for a while on the station square in Cairo and will in future guard the entrance of the Grand Egyptian Museum . Another colossus is housed in a specially built museum hall in Mit Rahina and is the main attraction of Memphis. The limestone statue measures 12.88 meters from head to knees and was discovered in 1820 by Giovanni Battista Caviglia . A third statue is a reworked statue of Sesostris I. It was assembled from granite fragments and caused quite a stir on an exhibition trip to the USA in 1989.

From the atrium behind the south gate comes a 8.7 × 4.7 meters wide Alabaster Sphinx that may Amenhotep III. and can now be seen in the open-air museum . In addition, a small sanctuary of the same king was found in the lower layers in the eastern district.

Archaeologists discovered a small temple of Ramses II in the southwest corner outside the surrounding wall. The sanctuary area is still preserved , which consists of a four-pillar room ( sacrificial table room ) and three parallel sanctuaries. A hypostyle serving as a hall of apparitions , of which a column can still be seen , may have been attached to the pillar space. In the temple there are numerous reused limestone blocks from the time of Amenhotep III. The blocks come from a small barge station for Ptah- Sokar , which probably stood at the demolished million year house. The local deities Ptah, Ptah- Tatenen , Sokaris and Sachmet were worshiped in the temple . The focus of the depicted scenes was the king himself. According to Rudolf Anthes , Ramses had the building erected on the occasion of his second Sedfest.

The Isheed tree was connected with the Sedfest , and according to contemporary inscriptions there was one in Memphis in Ramessid times. The reign of the king was carved into the leaves of the holy tree and his reign was thus placed under divine protection.

On the opposite side of the wall, Seti I built a small chapel that resembles the building of Ramses. It can be assumed that both served as station sanctuaries along the north-south axis due to their location .

The building activity of Ramses III. is attested in the Ptah district through individual statue fragments and inscriptions. In the Harris I papyrus , a granite temple is mentioned, which is said to have been clad with limestone, had gates made of gold and whose stone pylons "grew up to heaven". Two temples with the names "House of Ramses" and "Building of Ramses" are listed, although it is unclear exactly where the two buildings were and what purpose they served.

There was also a Sakhmet sanctuary on the site, of which a Ramesside temple gate has been preserved.

Herodotus reports of an allegedly 22-meter-long reclining colossus of Amasis , which , according to Strabo , was only erected later.

See also

literature

- Rudolf Anthes : With Rahineh 1955 . The University Museum, Philadelphia 1959.

- Rudolf Anthes: With Rahineh 1956 . The University Museum, Philadelphia 1965.

- David G. Jeffreys: The Survey of Memphis . tape 1 . Egypt Exploration Society, London 1985, ISBN 0-85698-099-4 .

- David G. Jeffreys, Jaromir Malek : Memphis 1986, 1987 . In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology. (JEA) Vol. 74 . 1988, ISSN 0307-5133 , pp. 25th ff .

- Dieter Arnold : The temples of Egypt . Artemis & Winkler, Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-7608-1073-X , p. 193-196 .

- Dieter Arnold: Lexicon of Egyptian architecture . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2000, ISBN 3-491-96001-0 , p. 197-198 .

- Julia Budka : Hut-ka-Ptah - The Temple of Ptah of Memphis . In: Kemet issue 2/2002 . Kemet-Verlag, 2002, ISSN 0943-5972 , p. 12-15 .

- Richard H. Wilkinson : The world of temples in ancient Egypt . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-18652-4 , pp. 114-115 .

Web links

- Hugues Perdriaud: Memphis: la préoccupante situation des ruines de Ramsès II dans le temple de Ptah. on thotweb.com. January 2000, accessed April 14, 2012 (French).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Dieter Arnold: The temples of Egypt. P. 193.

- ↑ a b c d Julia Budka: Hut-ka-Ptah. P. 12.

- ↑ Herodotus: Histories II. 99.

- ↑ Julia Budka: Hut-ka-Ptah. Pp. 12-13.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Julia Budka: Hut-ka-Ptah. P. 13.

- ↑ Herodotus: Histories II. 153.

- ↑ a b c d e f Dieter Arnold: The temples of Egypt. P. 194.

- ↑ a b Julia Budka: Hut-ka-Ptah. P. 14.

- ↑ Gerhard Haeny: Basilical systems in the Egyptian architecture of the New Kingdom. (= Contributions to Egyptian building research and antiquity. Issue 9), 1970.

- ↑ Eberhard Otto : Contributions to the history of the bull cults in Egypt. (= Hermann Kees (Hrsg.): Studies on the history and antiquity of Egypt. Vol. 13), Georg Olms Verlagsbuchhandlung, Hildesheim 1964, p. 16.

- ↑ a b c Julia Budka: Hut-ka-Ptah. P. 15.

- ↑ a b c Dieter Arnold: The temples of Egypt. P. 195.

- ^ Strabo: Geography, XVII. P. 31f.

- ^ Ramses to go to Grand Museum. Press release on Dr. Zahi Hawass . (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on January 23, 2012 ; accessed on April 15, 2012 .

- ↑ Mimi Mann: Research Hints That Ramses' Towering Colossus Is of Another King, Retouched. In: Los Angeles Times. December 3, 1989, accessed April 15, 2012 .

- ↑ Manfred Lurker: Lexicon of the gods and symbols of the ancient Egyptians (= Fischer. Bd. 16693.) 3rd edition, Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 2005, ISBN 978-3-596-16693-0 , p. 107.

- ↑ Julia Budka: Hut-ka-Ptah. Pp. 13-14.

Coordinates: 29 ° 51 ′ 8.4 " N , 31 ° 15 ′ 14.4" E