First Gulf War

| date | September 22, 1980 to August 20, 1988 |

|---|---|

| place | Iraqi-Iranian border area |

| output | Armistice ( status quo ante bellum ) |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

|

Ruhollah Khomeini |

|

| losses | |

|

min. 105,000 dead |

min. 262,000 dead |

Iraqi Invasion (1980)

Entegham - Kaman 99 - Khorramshahr - Sultan 10 - Scorch Sword - Abadan - Kafka - Ashkan - Morwarid - Dezful

Standoff (1981) Tavakol - Susangerd - H-3

Iranian offensives for the liberation of Iranian territory (1981–82)

Sam-ol-A'emeh - Tariq al-Qods - Fath ol-Mobin - Beit ol-Moqaddas - liberation of Khorramshahr

Iranian offensives in Iraq (1982–84)

Ramadan - Muslim Ibn Aqil - Muharram ol-Harram - Dawn 1 - Dawn 2 - Dawn 3 - Dawn 4 - Dawn 5 - Kheibar - Kurdish Uprising - Dawn 6 - Dawn 7 - Hawizeh Marshland

Iranian offensives in Iraq (1985-87)

Badr - Dawn 8 - 1. al-Faw - Dawn 9 - Karbala 1 - Karbala 2 - Karbala 3 - Fath 1 - Karbala 4 - Karbala 5 - Karbala 6 - Karbala 7 - Karbala 8 - Karbala 9 - Karbala10 - Nasr 4

Last year of the war (1988)

Beit ol-Moqaddas 2 - Anfal - Halabdscha - Zafar 7 - Tawakalna ala Allah - 2nd al-Faw - Shining Sun - 40 stars - Mersad

Tanker War

Earnest Will - Prime Chance - Eager Glacier - Nimble Archer - Praying Mantis

International Incidents

USS Stark - Iran Air Flight 655

The First Gulf War was a war between Iraq and Iran that lasted from September 22, 1980 to August 20, 1988 (also the Iran-Iraq War or Iraq-Iran War ; in contrast to the Iraq-Kuwait War, the Second Gulf War ).

After high human and economic losses on both sides, it ended without a victor through an armistice .

prehistory

Although the First Gulf War was primarily a struggle for supremacy in the Persian Gulf , the roots of the conflict go back many centuries. They had their origins in the rivalry between Mesopotamia (area of today's Iraq) and Persia (Iran). Before the expansion of the Ottoman Empire , parts of Mesopotamia belonged to Persia, which was ruled by the Aq-Qoyunlu dynasty. The rising Ottoman Empire under Murad IV annexed what is now Iraq in 1638. The weak Safavid ruler of Persia, Safi I , could not prevent this. This created a long-lasting border conflict; Between 1555 and 1918 Persia and the Ottoman Empire signed a total of 18 agreements to reorganize the border. Modern Iraq came into being when large parts of the former Ottoman Empire were partitioned between the victorious powers Great Britain and France after the First World War (according to the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916). The newly formed Iraq also inherited the border conflicts on its eastern border. The Iraq , Transjordan and Palestine came under British, Syria and Lebanon under French mandate administration.

Dispute over Khuzestan

In historical times, Chusistan was an independent, non- Semitic kingdom with the capital Susa and the cradle of the Elam Empire .

An ideologically advanced reason for the start of the war was the struggle for rule over the resource-rich province of Khuzestan . The struggle between Arabs and Persians, the liberation of "Arabistan", the majority of the population of Arab origin, from foreign rule. This ideology was successful on the Iraqi side, as Shiite Iraqis against Shiite Iranians determined the battle.

After Abd al-Karim Qasim took control of Iraq through a coup d'état, he declared on December 18, 1959:

“We do not want to refer to the history of the Arab tribes in Al-Ahwaz and Mohammerah Khorramshahr . The Ottoman Empire handed Mohammerah, which was part of Iraqi territory, over to Iran. "

Iraq began to support breakaway movements in Khuzestan and advanced its territorial claims at a meeting of the Arab League . The hoped for success did not materialize, however. Iraq, especially after the death of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and the rise of the Ba'ath Party , failed to comply with the existing agreement with Iran and sought the role of leader of the Arab world .

In 1969 then-Vice President of Iraq, Saddam Hussein stated:

"Iraq's dispute with Iran relates to Arabistan [Khuzestan], which is part of Iraqi soil and was annexed by Iran during foreign rule."

Soon after, Iraqi radio stations targeted Khuzestan, encouraging Iranian Arabs and even Baluchi to rise up against the Iranian government. Basra TV stations showed Khuzestan Province as a new Iraqi province called Nasiriyyah and gave all Iranian cities Arabic names.

The border river Shatt al-Arab (Arvand Rud)

One of the factors that contributed to hostilities between the two parties was the dispute over navigation rights on what the Arabs called Shatt al-Arab and Iran called Arvand Rud . The Treaties of Erzurum (1823/1847) and the Protocol of Constantinople signed in 1913 established 75 percent of the general demarcation between Iraq and Iran.

For the Schatt al-Arab / Arvand Rud shipping lane, shipping law applied from 1847 to 1913: demarcation on the east bank and use of the valley route for both parties. In the Treaty of 1847, the Ottoman Empire insisted that the question of sovereignty be left open, which was later to be resolved by a four-power arbitration commission. In 1920, Iran questioned the demarcation of the eastern bank, as the additional protocol of 1913 stipulated the curiosity: Iraqi pilots and Iraqi law on Iranian ships. The expansion of the port of Khorramshahr and the oil refinery of Abadan intensified the conflict.

With the Treaty of Saadabad on July 4, 1937 the first border treaty between Iraq and Iran was signed. The joint use was thus ratified by both sides, regardless of the precise demarcation that was later to be resolved by a commission. This commission never came to a conclusion, so the additional protocol of Saadabad still applied: Iraq was to administer the river. Between 1941 and 1946, control of the Shatt al-Arab or Arvand Rud was entirely on the side of the Allies .

On April 19, 1969, the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi terminated the Saadabad Treaty. In 1975 the Shah agreed in the agreement of Algiers with Iraq on the valley route line as the border. In return for the territorial concessions, Iran stopped providing financial support to the Iraqi Kurds . The Iraqi authorities complied with the Shah's request for greater surveillance of Ayatollah Khomeini , who was in exile in Iraq .

On September 17, 1980 - Khomeini had overthrown the Shah - Saddam Hussein terminated the Algiers Agreement. In return for the cessation of the acts of war that began shortly afterwards, he demanded that Iran should not only return the Tunb Islands and Abu Musa to the UAE but also grant Iraq full sovereignty in the Shatt al-Arab.

Iraq growing in strength, Iran shattered

Iraqi perspective

The then President of Iraq, Saddam Hussein , strove to achieve regional supremacy for his country. A successful campaign against Iran would make Iraq the dominant power in the Persian Gulf and the controller of a lucrative oil market. This ambitious goal was considered realistic by the political and military leadership of Iraq at the time. Iraq, unlike revolutionary Iran, enjoyed substantial diplomatic, military, and economic support from the Soviet Union , France, and the United States . He also received financial aid from other Arab countries (mainly Kuwait and Saudi Arabia ).

Saddam Hussein often alluded to Islamic expansion and the Arab conquest of Iran, thereby propagating his "anti-Persian" stance. On April 2, 1980, six months before the outbreak of war, he drew parallels to the Persian defeat in the 7th century at the Battle of Kadesia during his visit to al-Mustansiriyyah University in Baghdad and declared:

“On your behalf, brothers, and on behalf of the Iraqis and all Arabs, we tell these [Iranian] cowards and dwarves who seek revenge for al-Qadisiyah that the spirit of al-Qadisiyah and the blood and honor of the people of Al-Qadisiyah, who carried their mission on their spearheads, is greater than their efforts. "

Aware that the two superpowers were prepared to tolerate a far-reaching border shift in favor of Iraq that violated the territorial integrity of Iran, the Iraqi Baath regime did not aim at a direct annexation of Khusistan. The official goal was primarily to enforce the territorial autonomy of Chusistan within the Iranian state through the use of military force or to establish a formally independent buffer state between Iraq and Iran under Iraqi protection.

In August 1980, Saddam Hussein discussed his war plan with politicians from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait . Accordingly, the liberated Khusistan and Iranian Kurdistan should together form a separate Free Republic of Iran . Shapur Bakhtiar , the last prime minister, and Gholam Ali Oveissi, the last chief of staff of the Shah regime, who both fled via Iraq into exile in France and the USA, were to take over political leadership of the planned republic. Ahwaz was planned as the capital of the free republic .

Iranian weakness

As a result of the Islamic Revolution and the subsequent flight of the Shah in January 1979, Iran was not only politically but also militarily weakened. Escape, desertions and executions of soldiers had greatly reduced the former ability to act and the effectiveness of the armed forces of Iran.

In May 1979 there was an uprising among Iranians of Arab origin in the province of Khusistan , which is of immense importance for Iran because of its oil reserves . The uprising was initially suppressed using military means, but there could be no question of pacifying the province. Because of the question of the status of the Arab minority in Chusistan and that of the Shiite minority in Iraq, the relationship between the two countries deteriorated rapidly. On June 6, 1979, the West German ambassador to Iraq, Fritz Menne , reported to the Foreign Office:

“As long as Kurds, Turkmens or Azerbaijanis were involved, the minority struggles in Iran in the wake of the coup were observed in Iraq with interest but without direct involvement. That has changed with the flare-up of the Arabs' aspirations for autonomy in Khuzestan […]. Iraq needs to clarify a number of questions: Which of the Arab interests have priority? The preservation of the current, at least potentially powerful and in the Middle East conflict favorably disposed Tehran regime or the help for the Arab brothers in Iran in their autonomy efforts and the risk involved of endangering Tehran's position in the Middle East conflict? Are the Arabs closer to the skirt of Arab interests in the Middle East than the shirt of their immediate Iraqi interests? "

The aftermath of the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran was decisive for the dispute. Ayatollah Khomeini threatened to export the Islamic revolution to the other countries of the Middle East despite Iran's military inability at the time. Most of the Shah's armed forces had already been disbanded.

Khomeini and his supporters particularly detested the secularism of the Iraqi Ba'ath Party and hoped that Shiites in Iraq, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia would follow the Iranian example and rebel against their governments. This hope was supported by targeted propaganda by Iran, which called on the Shiite majority in Iraq to carry out a coup . At the same time, the destabilization of the country due to the revolution in Iran and its turning away from the western world represented a worthwhile goal for Saddam Hussein's urge to expand. He was convinced that the people of the "liberated" province of Khuzestan would join Iraq.

At a meeting between Hans-Dietrich Genscher and the Iraqi Foreign Minister Saadun Hammadi on July 6, 1979 in Baghdad, Foreign Minister Hammadi saw the following three possibilities for the further development of the situation in Iran:

“A) a coup by the Shah, whose influence and activity should not be underestimated even today, with units of the army still intact.

b) a coalition of Shah opponents of all shades outside the communist camp. This is the most likely solution, and the one most sympathetic to the Iraqi side. [...] He does not consider Khomeini to be able to really govern Iran.

c) A seizure of power by communist forces. However, he believes that the Soviet Union is not doing anything actively in this regard because it considers the pro-communist forces to be far too weak. "

Pre-war

On April 8, 1980, Ruhollah Khomeini called for the overthrow of the regime in Iraq:

"Saddam Hussein, who like the deposed Shah has exposed his anti-Islamic and inhuman face, intends to destroy Islam. [...]

Rise up before this corrupt regime destroys you in any way, cut off its criminal hand from your Islamic land. "

As a result, there were more and more attacks against Iraqi politicians. Tariq Aziz barely survived an attack on April 1, 1980. In the same month, some violent border fights took place, provoked by both sides. On April 30, 1980, the Iranian embassy in London was occupied by Iraqi-backed terrorists. The event came to be known as the " Siege of the Iranian Embassy, " which was ended on May 5, 1980 by the intervention of the British SAS . One hostage died during the liberation, another, an Iranian embassy employee, was previously executed by the hostage takers.

On September 4, 1980, Iranian units attacked the Iraqi cities of Mandali and Chanaqin , the Iraqi units responded on September 10, 1980 by occupying an area near Musian on the Shatt al-Arab. This 120 km² area was assigned to Iraq in the Treaty of Algiers, but not surrendered. On September 15, 1980, the OPEC oil conference in Vienna began with a scandal. With its veto, the Iranian delegation prevented the Iraqi oil minister from taking the chair. It was only on September 22nd that OPEC agreed to cut oil production.

Course of war

Iraqi attack

1980

On September 22, 1980 at 2 p.m. local time, the war began with massive air strikes on airports in the Iranian cities of Tehran , Tabriz , Kermanshah , Ahvaz , Hamadan and Dezful . At the same time, the Iraqi army advanced with a total of 100,000 men in three places in the oil and gas-rich province of Chuzestan .

The Iraqi war plan was based on plans from a British staff exercise in 1941 for a division to march into Khuzestan. The plan provided for the invasion of nine divisions. Three armored and two mechanized divisions were to take the province and finally secure the passes over the Zagros Mountains. Three infantry and one armored divisions were supposed to intercept a possible Iranian counter-attack on the northern flank, similar to the approach of the Anglo-Soviet invasion of 1941. The war plan called for operations to be completed after two weeks.

Although massive land gains were recorded after six days, it was not until October 24th after the battle of Khorramshahr that the city directly on the Shatt al-Arab was taken. On the northern border of the fight was also opened, but the main thrust was aimed at the province of Khuzestan . The war was designed as a blitzkrieg , especially documents found among Iraqi officers show a planned fighting time of a maximum of fourteen days ( Henner Fürtig : Der Iraqi-Iranian War , p. 62). At the end of 1980 the Iraqi army had gained 14,000 km² of land.

For the failure of the offensive, Fürtig analyzes on the Iraqi side "the withholding of certain troops to protect Baghdad, the unexpected resistance of the Arab Iranians and hesitant Iraqi action" (Fürtig, p. 69). The Iranian side was able to deploy almost 110,000 men from its regular armed forces , which meant that only a quarter of the armed forces, a maximum of 120 armored vehicles and fifty percent of the combat aircraft were available. This shortage could be compensated for by increasing the regular armed forces with more than 200,000 pasdaran , who lacked the military training but did not lack the will to fight. It is possible that Saddam Hussein had already recognized the military situation by the end of 1980 and, with his declaration of December 25, 1980 of a neutral zone, indicated the anticipation of the futility of further acts of war. In the case of territorial gains over a length of 600 km, but only 20 to 80 km deep on Iranian territory, one could no longer speak of a blitzkrieg .

By the end of 1980, more than 20,000 Iraqi and Iranian soldiers were dead.

1981

Iran's first major counter-offensive with 400 tanks led to the tank battle of Susangerd on January 5-11 . 50 Iraqi and 140 Iranian tanks were destroyed. The night attack in Operation Nasr on March 19 involved 100,000 Iranian fighters, including 30,000 Pasdaran and volunteers. The Iraqi army lost 700 armored vehicles in these battles, 10,000 soldiers died, 25,000 were wounded and 15,000 were taken prisoner. The Iranian army command postponed attacks at night because the Iraqi air force did not fly night missions.

On September 29, 1981, a Lockheed C-130 of the Iranian Air Force crashed on the return flight from the front with the entire army command. General Walliollah Fallahi, Chief of Staff of the Iranian Armed Forces, Defense Minister Colonel Musa Namju and his predecessor Colonel Javad Fakuri were among the dead. Allegedly, the machine caught fire and crashed. The investigative commission did not come to a final report, so that the question of sabotage has not yet been resolved. Fallahi is said to have been the first to openly admit that the war could not be won without American arms deliveries. Fallahi's successor as Commander-in-Chief of the Army was Ali Seyyed Shirazi , who was to be responsible for the success of the 1982 spring offensive and the driving back of the Iraqis from Iranian territory. Nonetheless, the original war of movement has now turned into a positional war in which Iranian troops rushed en masse against Iraqi positions.

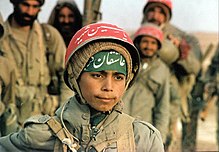

The tactics of the war resembled the First World War more and more in the course of the war , with high-casualty wave attacks on Iranian and rift systems on both sides (see trench warfare ). The extensive deployment of minors in Iranian voluntary associations ( Basitschi ), which, among other things, were used to fight tanks with detention mines , caused outrage and horror, especially in the western public .

Iranian offensive

1982

The offensive against Iraq began on March 27, and on April 29, fighting took place in the Howeiza area, and 12,000 to 15,000 Iraqi soldiers were taken prisoner. Up to this point in time, the Iraqi side counted between 60,000 and 100,000 soldiers killed and wounded, as well as 50,000 captured soldiers. On May 24, Khorramshahr was recaptured with the participation of around 70,000 Iranians , and on July 13, Iranian troops crossed the border into Iraq for the first time. On September 30th, the first wave attack with volunteers from the Basichi took place near Mandali , killing 4,000 Iranians.

On June 20, 1982, Saddam Hussein announced a unilateral armistice, which Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini rejected. According to this, information about Iranian troop movements, weak points and possible offensives are said to have been transmitted to Iraq by the US government via Saudi Arabia . Why Iran refused a ceasefire can be seen in the changed Iranian war goals. At the beginning of the war it was about the defense of the country, from mid-1982 it was about the conquest of Iraq and the export of revolution.

“There is no reason to end the war. [...] Iraq must be occupied, otherwise our revolution is doomed to failure. "

“If we cash Iraq, our two countries will be one country, the largest oil producer in the world. Together we would then be almost 60 million Muslims and have tremendous power over the world economy. Saudi Arabia and its American allies would be paralyzed, and the Gulf States would fall into our laps like ripe grapes. "

"I, spokesman for the nation, who has the trust of the people, say to you: the war will continue to the last drop of blood."

In September 1982, Saudi Arabia feared Iran would dominate Iraq and presented a peace plan that would have granted Iran reparations payments of US $ 70 billion. Iraq supported this plan, but the Iranian side called it blood money and rejected it. Rather, through its offensive successes, Iran had the goal of "liberating" the holy Shiite sites of Karbala and Najaf . The war escalated and the bombing of refineries and loading stations was intended to weaken the enemy economically on both sides.

1983

The Iranian spring offensive led to the conquest of 250 km² of Iraqi territory. The Operation Dawn 1 began on April 10, Operation Dawn 2 in the central portion of the front lines on 22 July, Operation Dawn 3 on 30 July and Operation Dawn 4 on 20 October 1983. By the end of 1983 there were 350,000 deaths on both sides , 300,000 wounded and 90,000 prisoners.

1984

The Iranians' spring offensive began again near Basra with the voluntary Basichi . By February 15, the commander-in-chief had managed to pull together 500,000 armed forces in the middle section of the front between Mehrān and Dehloran under Operation Dawn 5 and Operation Dawn 6 . Iranian troops occupied the marshland around Howeiza and the oil island Majnun. The Iraqi army countered an Iranian attack on the Basra – Baghdad highway. These battles claimed the lives of 30,000 soldiers. Nevertheless, on October 18, there was a new Iranian offensive, Operation Dawn 7 .

1985

The Iranian spring offensive (Operation Badr) from March 11 to 23 near Basra cost the highest blood toll of the war during a battle with 30,000 dead and 100,000 wounded on the Iranian side and 12,000 dead on the Iraqi side. The offensive at Howeiza a month later resulted in 20,000 deaths, while 300 to 500 Iraqi armored vehicles were destroyed in the process.

1986

The Committee against the Iran-Iraqi War stated on January 18, 1986:

“The Iraqi regime started the war, but the regimes of both countries are now responsible for continuing the war. The Iranian regime is expanding the war on Iraqi soil, the Iraqi regime is escalating the war by attacking the civilian population and using chemical weapons. As a result, the war will never end [...] In the past five years since the war began, the leading states in East and West have not undertaken a single peace initiative to end this war. Arms exports make the continuation of the war possible [...]. "

On the 7th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution, Operation Dawn 8 started on February 9, 1986 , which led to the crossing of the Shatt al-Arab and the conquest of the Iraqi port city of Faw . Iranian troops reached the border with Kuwait on February 12, cut off Iraq from direct access to the Persian Gulf and trapped the Iraqi fleet in Umm Qasr .

On February 14, Operation Dawn 9 targeted the northern sector of the front and almost resulted in the capture of the Iraqi city of Sulaimaniyya . The Iraqi army countered in May by capturing the Iranian city of Mehran in the province of Ilam , before being repulsed by Iranian troops in July as part of the Iranian offensive Karbala 1 . The AWACS aircraft made available to Saudi Arabia from June 1986 onwards are said to have delivered data to Iraq, which used them to defend the city of Basra , with a high degree of probability .

The Karbala 2 offensive, which began on July 31 on the northern section of the front, and the Karbala 3 offensive, which began on September 1 on the southern section of the front, enabled the Iranian troops to expand their positions on conquered Iraqi territory. In September, however, the Iraqis succeeded in retaking some positions in the Iranian-occupied Majnun Islands. On December 24th, the Iranians launched another offensive south of Basra with Karbala 4 . Four islands (Umm al-Rassas, Umm Babi, Qate, Schoail) in the Shatt el-Arab were particularly fiercely contested. The Iranian successes remained limited, in a counterattack the Iraqis were able to inflict great losses on the Iranians and restore the connection to Umm Qasr and thus to the Persian Gulf. Of the 50,000 Iranian soldiers involved, up to 30,000 are said to have fallen by December 27, according to Iraqi information, in what Iraq described as the “greatest military debacle” of Iran since the war began. The Iraqi side lost 12,000 men.

1987

On January 9, 1987, the largest Iranian offensive of the war, Operation Karbala 5 , began north of Basra and was supposed to lead to the encirclement of the port city. The Iranians managed to overrun the Iraqi border town of Duayji (opposite Shalamcheh), but only partially to break through the Iraqis' deep defense lines. This was due on the one hand to strong Iraqi resistance and on the other to logistical problems on the Iranian side. The Iraqis were able to assert themselves behind Lake Asmak (fish lake or fish canal, an Iraqi fortification line) and the Jasim River. Iranians' bridgeheads were destroyed. The Iranian troops, reinforced by the Revolutionary Guards to more than 100,000 men, were able to occupy almost 100 square kilometers of Iraqi territory, but mainly only marshland. The Iranians were only stopped ten kilometers east of the port of Basra. During their counterattack, Iraqi troops briefly advanced as far as the Iranian-occupied east bank of the Shatt el-Arab without being able to stop there. By January 12, at least 12,000 Iranians and 7,000 Iraqis are said to have been killed. At the end of January Iraqi troops succeeded in retaking some islands in the Shatt el-Arab and the shores of Lake Asmak, but an Iraqi attempt to land on the Faw peninsula failed. After that, the fighting subsided , but Karbala 5 wasn't officially ended until the end of February. By then, 40,000 Iranians and 10,000 Iraqis are said to have fallen. Iraq even reported 70,000 Iranians dead, and Iran reported 30,000 Iraqis dead.

The Iranian offensive Karbala 6 , which began on January 14, targeted the threat to the Iraqi capital on the central section of the front between Sumar and Mandali, about 100 kilometers east of Baghdad. The Iranians managed to recapture four Iranian heights that had been occupied by Iraqi since the beginning of the war, but their advance on Baghdad was halted. In the three days of fighting a total of 20,000 men fell on both sides on this section of the front.

The Iranian offensive Karbala 7 was directed from March 4th against the city of Haji Omran in Iraqi Kurdistan on the northern sector of the front. The Iranians were able to advance four kilometers, inflict heavy losses on the Iraqis and occupy a small Iraqi area.

After reinforcement by 100,000 fresh troops, Iran began the Karbala 8 offensive east of Basra on April 6 . The al-Ghadeer Brigade of the Revolutionary Guards and the 21st Brigade of the Iranian Army succeeded in pushing the 1st and 4th Battalions of the 417th Iraqi Brigade back behind Lake Asmak. The Iranians lost 5,000 men by April 9, the Iraqis 2,600 men.

The Iranian offensive Karbala 9 was directed from April 9th against the central section of the front in the Qasr-e Shirin area . From April 26th to 29th, Iranian troops tried to come to the aid of allied pro-Iranian Kurdish militias against Iraqi attacks as part of their offensive Karbala 10 directed against Sulaimaniya . The Iraqi garrison town of Mawat near Sulaimaniya was enclosed and conquered again for the first time on June 22nd in early May. On the central sector of the front, Iraqi attacks on the Iranian border town of Mehran on June 24 and July 6 failed, as did an Iranian counterattack on September 14.

From August 23, Basra was attacked by Iranian rockets and artillery almost daily, and Baghdad and Mosul were also targeted by Iranian rocket attacks. The Iraqi oil production platform Mina al-Bakr and the Iraqi fleet in Umm Qasr have increasingly been the target of repeated Iranian speedboat attacks. In turn, the Iraqi Air Force and Iraqi missiles attacked numerous Iranian cities and oil islands in the Persian Gulf.

On September 18, Iranian and allied Kurdish troops captured the Iraqi garrison town of Kani Masi on the northern section of the front, and on October 5 they advanced on the Iraqi city of Kifri. However, on the central sector of the front, the Iraqis were able to stop an Iranian attack on November 17th.

On December 20, another Iranian offensive began on the southern section of the front near Subeidad (200 kilometers northeast of Basra), but the attack by 6000 Iranians on four Iraqi battalions did not lead to a decisive breakthrough despite the brief Iranian conquest of 30 km² Iraqi territory. In preparation for a new major offensive at the end of 1987, the Iranian side had drawn together almost 300,000 men on the southern sector of the front.

Iraqi Recapture 1988

In view of US arms deliveries ( Irangate ), Chinese arms deliveries ( Silkworm missiles) and their own armaments program (first Iranian submarine), the Iranian navy and the Iranian air force were able to operate increasingly successfully. On December 18, January 9 and January 22, attacks by Iranian speedboats on Iraqi oil loading terminals in the Persian Gulf (including al-Ameeq) failed. The Iranians lost 22 of 63 speedboats used, but attacked al-Ameeq again unsuccessfully on January 28, 30 and February 1. Iranian warplanes, missiles and far-reaching artillery bombed Iraqi cities close to the front. Iraqi counter-attacks repeatedly hit Tehran, and Turkish mediation to end the renewed city war failed.

An Iranian offensive began on January 15 on the northern sector of the front, but the Iranians were stopped in the Mawat area on January 18. However, when his helicopter was shot down, the commander of the 5th Iraqi Army Corps responsible for this section of the front was killed. The Iranian Operation Dawn 10 , which started on March 14 on the northern section of the front with the help of allied Kurdish militias , led to the occupation of 900 km² of Iraqi territory by March 22, the conquest of the Iraqi cities of Halabja and Churmal and the poison gas attack on Halabja . Counter-attacks by the Iranian NLA and pro-Iraqi Kurds in Iranian Kurdistan failed.

On the central sector of the front, an Iranian offensive was directed on March 18 against the Iraqi-occupied Iranian city of Nowsud.

Another Iranian offensive since March 24th on the northern sector of the front could only be stopped on April 2nd in front of Sayid Sadiq. In their counterattack, the Iraqi troops succeeded in inflicting heavy losses, especially on the Kurdish militias allied with Iran. Another Iranian offensive from Penjwin failed on April 13th.

The large-scale Iraqi counter-offensive on the southern sector of the front led on April 17 to the recapture of the Iraqi city of Faw and the territories lost the previous year. Whereas the Iranian conquest of Faw in 1986 took three months, the Iraqis managed to recapture it within 34 hours. During the reconquest, the Iraqi troops had advanced through the Kuwaiti islands of Warba and Bubiyan to the Faw peninsula. On May 25, the 3rd Iraqi Army Corps, east of Basra, liberated the areas occupied by the Iranians in January 1987 and captured the Iranian border town of Shalamcha. An Iranian counter-offensive undertaken on June 11 east of Lake Asmak against Shalamcha failed on June 13, while the Iraqi counter-attack on June 14 pushed the Iranians back across the border.

Also on the northern section of the front, where Iraqi troops had already recaptured some mountain ranges on June 10, an Iraqi counter-offensive began on June 15 under the name Mohammed Rasul-ul-Allah , which led to the recapture of 32 mountain ranges by June 19. At the same time, the NLA took action from June 18 to June 21 as part of its “Forty Stars” offensive on a 50-kilometer-wide front against two Iranian divisions. Together, Iraqi troops and the NLA were able to recapture the Iranian city of Mehran on the central section of the front on June 19.

On June 25, Iraqi troops also recaptured the Majnun Islands, which had been under Iranian occupation since 1984, and the Huwaisa swamps north of Basra, whereupon thousands of Iranians were taken prisoner and the most important part of the Iranian front gradually collapsed.

Air war

The strike planned by the Iraqi Air Force, similar to the six-day war of the Israeli Air Force to destroy the Iranian aircraft on the ground on the first day of the fight, failed. On the one hand, the predominantly deployed MiG-23 fighter aircraft failed to approach the target at Iranian airports. Furthermore, many bomb hits were inaccurate, since the Iraqis had only practiced attacks on large targets such as cities and settlements in peacetime. The Iranian Air Force also had hardened hangars in some cases . In addition, the Iraqi Air Force got its information about the Iranian locations mainly from deserters. The military had refrained from previous reconnaissance flights, as well as reconnaissance missions after attacks in order to identify possibly insufficiently hit targets. On the first day, three Iranian warplanes and a transport plane were destroyed, while the Iraqis themselves lost three planes to anti-aircraft fire. The attack left all Iranian military airfields operational. During the first few weeks of the war, the Iraqi Air Force was unable to achieve air sovereignty against the few but highly effective F-14 fighter jets of the Iranian Air Force. The failure of the attempt to destroy the Iranian air force right from the start turned out to be a disadvantage for the Iraqis in the first years of the war.

The consequent arming of the Iraqi Air Force u. a. with fighter aircraft of the type Mirage F1 ultimately led to an air superiority from the war year 1984, because Iran lacked the spare parts. However, the training of the Iranian pilots was superior to that of the Iraqi pilots. The Iranian pilots had been trained in the United States with flexible combat tactics, while the Iraqis had been trained according to Soviet combat doctrine. This led to the fact that the Iranians, despite being numerically inferior, often held the air dominion on sections of the front that were important to the war effort. This fact was particularly devastating in the case of the Iranian counter-attacks that led to the withdrawal of Iraqis from Iranian territory. In the battle for Khorramshahr , which marked the end of Iraqi offensive movements in Iran, 58 Iraqi planes were shot down, while only four fighter planes were lost on the Iranian side. This balance only changed towards the end of the Eight Years' War, when the Iraqi pilots learned drastic improvements in their air tactics from French instructors.

City war

Air strikes

On February 10, 1983, the Iraqi air force bombed Iranian cities for the first time (Riyahi, p. 120), and on May 30, 1983, Iran also threatened to bomb Iraqi cities. 1985 saw the expansion of the so-called city war . The Iraqi air force flew attacks with Tu-22 bombers and the freshly delivered MiG 25 against Tehran.

Helge Timmerberg remarked laconically:

"Iraqis don't drop more than a dozen bombs per attack, and the chance of being hit in this huge city is less than dying in a taxi."

During the Iranian Operation Karbala 5 in 1987, 65 Iranian cities were attacked by the Iraqi side as a countermeasure over 42 days. By the end of the war, 2,695 Iraqi air strikes on Iranian cities died, according to Iranian sources, 8,848 people and 38,883 were injured. In the air strikes on Iraqi cities, 300 people died and 1,000 were injured by the end of 1987.

Missile attacks

Already on 20 November 1980, the first Iraqi attack with 53 carried out ballistic missiles of the type R-17 . Iraq fired 516 ballistic missiles at Iran in the course of the war, the target areas were predominantly cities. A rocket hit on January 10, 1987 in a primary school in Borudscherd killed 67 children.

Iran, which received 54 R-17s from Libya at the beginning of 1985 , responded to the rocket attacks by Iraq immediately after the delivery by launching at least 14 R-17 rockets on Baghdad and Kirkuk. 8 R-17s were shot down in 1986, 18 in 1987 and 77 in 1988. The target areas were Baghdad (66), Mosul (9), Kirkuk (5), Takrit (1) and Kuwait (1). Iraq responded to the Iranian missile attacks in 1987 with a newly developed, extended-range R-17 under the name Al Hussein and the expansion of the attacks to Iranian cities previously outside the range of the R-17, such as Tehran , Qom and Isfahan . The rocket attacks from February 29 to April 20, 1988, with 189 R-17 and Al-Hussein rockets on Iranian cities, were the culmination of the urban war. Over 2,200 people were killed and more than 10,000 injured in the Iraqi missile attacks during the war.

Use of children and young people on the Iranian side

The Basij-e Mostaz'afin volunteer militia also recruited children and young people during the First Gulf War, some of whom were used as human "mine clearers". The parents of the children were promised bonuses if they died as “ martyrs ”. The children had plastic keys hung around their necks that were supposed to unlock the gate to paradise. Half a million plastic keys have been imported from Taiwan. 95,000 Iranian child soldiers died in the First Gulf War. Donkeys and mules are said to have been used before children were used. However, they fled in a panic as soon as the first animals were torn apart by the explosions.

Mohsen Rezai , the then commander of the Pasdaran and thus also the Basij, was accused by the "Association of Mothers of Child Soldiers " of being responsible for the deaths of thousands. One indictment in court was dismissed; the current revolutionary leader Ali Khamene'i was then commander in chief of the armed forces.

Bahman Nirumand quotes a 1984 edition of the Ettelā'āt newspaper :

- You used to see volunteer children, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen and twenty year olds like buds in fields that had blossomed at dawn. They went over minefields. Her eyes saw nothing, her ears heard nothing. And a few moments later you could see clouds of dust rising. When the dust settled again, nothing of them could be seen. According to Ettelaat, this situation has improved, because before entering the minefields, the children wrap themselves in blankets and roll on the floor so that their body parts do not fall apart after the mines detonated ...

Use of chemical warfare agents

The war was marked by extreme brutality and on the Iraqi side also included the large-scale and ruthless use of chemical weapons . Iraq has been importing technical equipment since 1975 and purchasing the associated technology on a large scale from 150 multinational arms companies, including 24 from the United States.

As UNMOVIC found in its 2006 report, Iraq had already produced ten tons of mustard gas (lost) in 1981 . Over the years, Tabun , Sarin and VX were added. Iraq had produced 3850 tons of chemical warfare agents by 1991, of which 3300 tons were ammunitioned. The chemical weapons program of Iraq thus produced over 100,000 explosive devices by 1988, which were classified as

- Air bombs (250, 400 and 500 kg): 19,500 pieces

- Artillery ammunition (155 mm shells): 54,000 pieces

- Missile warheads (122 mm missile launchers): 27,000 units

were used on Iranian positions and against the civilian populations of Iran and Iraq.

In its declaration of November 18, 1980, the Iranian Foreign Ministry already stated that the Iraqi army had used chemical weapons on a large scale and that these were apparently dropped in canisters over Iranian positions.

On August 9, 1983, there was a poison gas attack on the Rawanduz – Piranschahr trunk road (Fürtig, p. 81). The next known use of poison gas took place on January 26, 1984, then on February 29, 1984. The victims were shown to the international press in Tehran. On February 16, 1984, the Iranian Foreign Minister published 49 cases of chemical weapons use on the Iraqi side on a total of forty sectors of the front, killing 109 soldiers. The Iranians injured by poison gas on March 2, 1984 were flown to Austria, Sweden and Switzerland for treatment, the Iranians injured on March 15, 1984 to Germany for treatment (Riyahi, p. 128).

List of chemical attacks in Iraq:

| year | Attacks | dead | Injured |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | 20th | 19th | 2,515 |

| 1984 | 47 | 34 | 2,343 |

| 1985 | 90 | 51 | 10,546 |

| 1986 | 47 | 11 | 6,537 |

| 1987 | 33 | 5390 | 16,670 |

| 1988 | 47 | 260 | 4,284 |

| total | 284 | 5,765 | 42,931 |

Saddam Hussein also used poison gas against the ethnically Kurdish civilian population of Iraq during the Anfal operation . The poison gas attack on Halabja and the poison gas attack on Sardasht became known to the world public .

The United Nations Security Council had solid evidence of the use of poison gas on the Iraqi side on March 26, 1984, and on Iraqi soil, according to Iraqi reports. The UN resolution 582 of February 24, 1986 first established the use of poison gas and warned both parties to the conflict (Iran and Iraq) to adhere to the Geneva Protocol. UN resolution 612 of May 9, 1988 expected both parties to forego the use of chemical weapons in the future.

This set the global political response. In the First Gulf War, both warring parties were accused of using poison gas.

Military confrontations with other states

Osirak

On June 7, 1981, there was an Israeli air strike with eight F-16 fighter planes on the Iraqi nuclear reactor under construction in Osirak , in which a French technician was killed. Israel justified the blow against Iraq by stating that it was a preventive measure against the Iraqi nuclear weapons program, as Israel suspected the reactor was less used for civilian electricity generation than for the construction of an Iraqi nuclear weapon. To this day it has remained unclear whether the reactor was to be used for civil or military purposes. The Israeli air strike against the construction site of the Iraqi nuclear reactor Osirak was seen as an attack that was clearly prohibited under international law.

Tanker war

On May 21, 1981, a tanker sailing under the Panamanian flag was sunk. After an Exocet missile hit the Iranian offshore field Nowruz on March 2, 1983 in order to internationalize the conflict and prevent Iran from exporting oil, the so-called tank war began .

It involved ninety percent Iranian oil and at least 250 tankers were damaged or destroyed in the course of the tank war. On May 14, 1988, the largest oil tanker in the world at the time , the Seawise Giant , was badly damaged by the Iraqi Air Force. In detail, there were attacks on 45 ships by the end of 1983, 67 attacks in 1984, 105 ships in 1986 and 34 ships by May 1987.

The attacks against Iranian oil loading stations (including Bandar-e Chomeini and Bandar-e Maschur) and tankers were carried out by the Iraqi Air Force mainly with the Super-Étendard aircraft equipped with Exocet cruise missiles from France in mid-1983 . The Iranian attacks on ships supposedly carrying Iraqi oil were carried out with sea mines , guided weapons and ship fire by the Iranian frigates . The dangerous stretch between the island of Charg, used as an oil terminal, and the island of Larak off Bandar Abbas was nicknamed "Exocet Alley" by seafarers.

As a result of the tanker war , Iranian exports fell to 700,000 barrels a day in early 1984 , only to rise again to 1.6 million barrels in the middle of the year. In 1985 the tanker war resulted in a drop to 750,000 barrels, with a peak load of 3.2 million barrels in 1982 and an average production of 1.2 million in 1980.

Iraq, whose production facilities were attacked and destroyed by Iranian fighter planes as early as the end of 1980, especially those near Basra , Kirkuk and Mosul , had to record a drop from the original 5.2 million barrels of total production per day to 1.9 million barrels. After Syria, one of Iran's few allies, banned the flow of Iraqi oil through its territory on April 10, 1982, Iraq's exports were reduced to 600,000 barrels a day. The Gulf Cooperation Council , which was hastily founded due to the Gulf War , stood by Iraq's side in the event of its oil revenues failing and supported Iraq with 50 billion dollars in loans and donations. Iraq spent 60 percent and Iran 43 percent of its budget on warfare (Fürtig, pp. 68/90).

US intervention

The ongoing attacks on international tanker traffic resulted in a strong US presence. After Kuwait asked for protection for its tankers in 1986, the United States re-flagged eleven tankers and now escorted the now US ships in Operation Earnest Will . Iranian ships had already attacked Kuwaiti tankers beforehand, and Iran threatened a sea blockade in the Strait of Hormuz , which, however, was regarded as implausible as it would also have affected Iranian exports to a considerable extent. 37 US sailors died in an Iraqi missile attack on the frigate USS Stark (FFG-31) on May 17, 1987 . After the USS Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58) ran into an Iranian sea mine on April 14, 1988 and 10 sailors were injured, the United States started Operation Praying Mantis on April 18, 1988 , which involved the destruction of two Iranian oil platforms and of several ships. At the same time, Iraq recaptured the Faw Peninsula .

Shot down of a passenger plane

An incident occurred on July 15, 1987. Two Iranian passenger planes, Iran Air Flight 1251 and 1253, which were en route to Mecca , were sighted by American warships at 11:00 and 11:04 a.m. local time and received several kill warnings. Iran rated this as a “blatant violation of international law”.

The shooting down of the Iranian passenger plane with flight no. IR655 by the cruiser USS Vincennes (CG-49) on July 3, 1988, in which all 290 passengers and the crew were killed, also contributed to the adoption of UN Resolution 598 on the Iranian side.

UN Resolution 598 and the Armistice

On July 18, 1988, Ruhollah Khomeini finally agreed to recognize UN Security Council Resolution 598 of July 20, 1987 and UN Security Council Resolution 582 of February 24, 1986 and thus a ceasefire , Saddam Hussein did so beforehand. The armistice came into effect on August 20, 1988 at 3:00 a.m. A peace treaty does not exist to this day.

The report by UN Secretary General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar of December 9, 1991 (S / 23273) explicitly stated the " aggression of Iraq against Iran" by triggering war and disrupting international security and peace.

weapons shipments

The arms deliveries from various countries ensured that the war was prolonged, as both warring parties were in fact lacking weapons and equipment as early as 1982. While Iran was able to use up the shah's accumulated arsenal, Iraq was systematically upgraded for armed conflict and provided with information ( AWACS ) and toleration.

The Economist published a table in 1987 of the increasing "imbalance" of the warring factions in heavy equipment:

| Iraq | Iran | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1987 | 1980 | 1987 | |

| Armored vehicles | 2700 | 1740 | 4500 | 1000 |

| Warplanes | 332 | 445 | 500+ | 65 * |

| helicopter | 40 | 500 | 150 | 60 |

| artillery | 1000 | 1000+ | 4000+ | 1000+ |

The material superiority of the Iraqis in terms of military equipment was 3: 1 in 1986, in some areas even 8: 1 (Fürtig, p. 144), which Iran, however, compensated for through superior personnel.

In 1984 Iraq became the world's largest arms importer, with arms valued at $ 7.7 billion. From 1981 to 1985 arms were shipped to Iraq for $ 23.9 billion, and to Iran in the same period for $ 6.4 billion.

- Weapons and material support provided to both warring parties: Ethiopia, Brazil, Chile, PR China, GDR, France, Italy, North Korea, Austria ( Noricum scandal ), Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, USA, USSR and United Kingdom. In addition to the arms sales in the context of the Iran-Contra affair , the USA supplied Iran covertly via South Korea with spare parts for the F-4 Phantom II and ammunition via Taiwan, Argentina and South Africa.

- Delivered to Iraq only: Egypt, Belgium, Federal Republic of Germany, Jordan, Yugoslavia, Kuwait, Morocco, Pakistan, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the United Arab Emirates.

- Delivered to Iran only: Algeria, Argentina, Greece, Israel, Libya, Mexico, South Korea, South Yemen, Syria, Taiwan, Turkey and Vietnam.

Israeli arms deliveries to the Islamic Republic of Iran were particularly significant at the start of the war when they made up over 80 percent of Iran's arms imports. Between 1980 and 1983, Israel delivered arms worth the equivalent of 500 million euros, most of which were paid for in oil and transacted via Larnaca Airport in Cyprus . The Israeli arms deliveries lasted until 1988.

List of arms sales to Iraq

| country | specification | description | delivery | number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | D-30 122mm | Pipe artillery | 1985-1989 | 210 |

| Egypt | M-46 130mm | Pipe artillery | 1981-1983 | 96 |

| Egypt | RL-21 122mm | Rocket launcher | 1987-1989 | 300 |

| Egypt | T-55 | tank | 1981-1983 | 300 |

| Egypt | Walid | Personnel carriers | 1980 | 100 |

| Brazil | Astros II MLRS | Rocket launcher | 1984-1988 | 67 |

| Brazil | EE-11 Urutu | Personnel carriers | 1983-1984 | 350 |

| Brazil | EE-3 Jararaca | armored vehicle | 1984-1985 | 280 |

| Brazil | EE-9 Cascavel | armored vehicle | 1980-1989 | 1026 |

| Brazil | EMB-312 Tucano | Training aircraft | 1985-1988 | 80 |

| Brazil | Astros AV-UCF | Fire control radar | 1984-1988 | 13 |

| Federal Republic of Germany | MBB / Kawasaki BK 117 | helicopter | 1984-1989 | 22nd |

| Federal Republic of Germany | MBB Bo-105C | helicopter | 1979-1982 | 20th |

| Federal Republic of Germany | MBB Bo-105L | helicopter | 1988 | 6th |

| Federal Republic of Germany | Roland | Air defense system | 1981 | 100 |

| Denmark | Al-Zahraa | Ro-Ro ship | 1983 | 3 |

| GDR | T-55 | tank | 1981 | 50 |

| France | Mirage F-1BQ | Fighter plane | 1982-1990 | 15th |

| France | Mirage F-1EQ | Fighter plane | 1980-1982 | 105 |

| France | SA-312H Super Frelon | helicopter | 1981 | 6th |

| France | SA-330 Puma | helicopter | 1980-1981 | 20th |

| France | Aérospatiale SA 341 | helicopter | 1980-1988 | 38 |

| France | AMX-GCT / AU-F1 | Pipe artillery | 1983-1985 | 85 |

| France | AMX-10P | Armored personnel carriers | 1981-1982 | 100 |

| France | AMX-30 D | Armored recovery vehicles | 1981 | 5 |

| France | ERC-90 | armored vehicle | 1980-1984 | 200 |

| France | M-3 VTT | Personnel carriers | 1983-1984 | 115 |

| France | VCR-TH | Anti-tank weapon | 1979-1981 | 100 |

| France | Rasit | radar | 1985 | 2 |

| France | Roland | Air defense system | 1982-1985 | 113 |

| France | TRS-2100 Tiger | radar | 1988 | 1 |

| France | TRS-2105/6 Tiger-G | radar | 1986-1989 | 5 |

| France | TRS-2230/15 Tiger | radar | 1984-1985 | 6th |

| France | Volex | radar | 1981-1983 | 5 |

| France | AM-39 Exocet | Anti-ship missile | 1979-1988 | 352 |

| France | ARMAT | Radar missile | 1986-1990 | 450 |

| France | AS-30L | Air-to-surface guided missile | 1986-1990 | 240 |

| France | HOT | Anti-tank missile | 1981-1982 | 1000 |

| France | R-550 Magic-1 | Air-to-air missile | 1981-1985 | 534 |

| France | Roland-2 | Anti-aircraft missile | 1981-1990 | 2260 |

| France | Super 530 F | Air-to-air missile | 1981-1985 | 300 |

| Great Britain | Chieftain | tank | 1982 | 29 |

| Great Britain | Cymbeline | radar | 1986-1988 | 10 |

| Italy | Agusta A109 | helicopter | 1982 | 2 |

| Italy | Sikorsky S-61 | helicopter | 1982 | 6th |

| Italy | Stromboli class | ship | 1981 | 1 |

| Jordan | S-76 Spirit | helicopter | 1985 | 2 |

| Yugoslavia | M-87 hurricane 262 mm | Rocket launcher | 1988 | 2 |

| Canada | PT-6 | Aircraft engine | 1980-1990 | 152 |

| Austria | GHN-45 155mm | Pipe artillery | 1983 | 200 |

| Poland | Mi-2 / Hoplite | helicopter | 1984-1985 | 15th |

| Poland | MT-LB | Personnel carriers | 1983-1990 | 750 |

| Poland | T-55 | tank | 1981-1982 | 400 |

| Poland | T-72 | tank | 1982-1990 | 500 |

| Romania | T-55 | tank | 1982-1984 | 150 |

| Switzerland | Pilatus PC-7 | Training aircraft | 1980-1983 | 52 |

| Switzerland | Pilatus PC-9 | Training aircraft | 1987-1990 | 20th |

| Soviet Union | Il-76M / Candid-B | Transport plane | 1978-1984 | 33 |

| Soviet Union | Mi-24D / Mi-25 / Hind-D | Attack helicopter | 1978-1984 | 12 |

| Soviet Union | Mi-8 / Mi-17 / Hip-H | Transport helicopter | 1986-1987 | 37 |

| Soviet Union | Mi-8TV / Hip-F | Transport helicopter | 1984 | 30th |

| Soviet Union | Mig-21bis / Fishbed-N | Fighter plane | 1983-1984 | 61 |

| Soviet Union | Mig-23BN / Flogger-H | Fighter plane | 1984-1985 | 50 |

| Soviet Union | Mig-25P / Foxbat-A | Fighter plane | 1980-1985 | 55 |

| Soviet Union | Mig-25RB / Foxbat-B | Fighter plane | 1982 | 8th |

| Soviet Union | Mig-29 / Fulcrum-A | Fighter plane | 1986-1989 | 41 |

| Soviet Union | Su-22 / Fitter-H / J / K | Fighter plane | 1986-1987 | 61 |

| Soviet Union | Sukhoi Su-25 | Ground attack aircraft | 1986-1987 | 73 |

| Soviet Union | Tupolev Tu-22 | Bomb plane | 1975 | 14th |

| Soviet Union | 2A36 152 mm | Pipe artillery | 1986-1988 | 180 |

| Soviet Union | 2S1 122 mm | Pipe artillery | 1980-1989 | 150 |

| Soviet Union | 2S3 152 mm | Pipe artillery | 1980-1989 | 150 |

| Soviet Union | 2S4 240 mm | mortar | 1983 | 10 |

| Soviet Union | 9P117 / SS-1 Scud TEL | Missile launch pad | 1983-1984 | 10 |

| Soviet Union | BM-21 degrees 122 mm | Rocket launcher | 1983-1988 | 560 |

| Soviet Union | D-30 122mm | cannon | 1982-1988 | 576 |

| Soviet Union | M-240 240mm | mortar | 1981 | 25th |

| Soviet Union | M-46 130mm | Pipe artillery | 1982-1987 | 576 |

| Soviet Union | 9K35 Strela-10 | rocket | 1985 | 30th |

| Soviet Union | BMD-1 | Armored personnel carriers | 1981 | 10 |

| Soviet Union | PT-76 | light tank | 1984 | 200 |

| Soviet Union | 9P31 | rocket | 1982-1985 | 160 |

| Soviet Union | Long track | radar | 1980-1984 | 10 |

| Soviet Union | SA-8b / 9K33M Osa AK | Air defense system | 1982-1985 | 50 |

| Soviet Union | Thin skin | radar | 1980-1984 | 5 |

| Soviet Union | 9M111 | Anti-tank missile | 1986-1989 | 3000 |

| Soviet Union | 9K35 Strela-10 | Anti-aircraft missile | 1985-1986 | 960 |

| Soviet Union | KSR-5 | Anti-ship missile | 1984 | 36 |

| Soviet Union | Ch-28 | Radar missile | 1983-1988 | 250 |

| Soviet Union | R-13S / AA-2S atoll | Air-to-air missile | 1984-1987 | 1080 |

| Soviet Union | R-17 / SS-1c Scud-B | Surface-to-surface missile | 1974-1988 | 819 |

| Soviet Union | AA-10 Alamo | Air-to-air missile | 1986-1989 | 246 |

| Soviet Union | AA-6 Acrid | Air-to-air missile | 1980-1985 | 660 |

| Soviet Union | AA-8 aphid | Air-to-air missile | 1986-1989 | 582 |

| Soviet Union | SA-8 / 9M33M | Anti-aircraft missile | 1982-1985 | 1290 |

| Soviet Union | 9K31 Strela-1 / 9M31 | Anti-aircraft missile | 1982-1985 | 1920 |

| Soviet Union | 9K34 Strela-3 | Anti-aircraft missile | 1987-1988 | 500 |

| Czechoslovakia | L-39Z Albatros | Training aircraft | 1976-1985 | 59 |

| Czechoslovakia | BMP-1 | Armored personnel carriers | 1981-1987 | 750 |

| Czechoslovakia | BMP-2 | Armored personnel carriers | 1987-1989 | 250 |

| Czechoslovakia | OT-64C | Personnel carriers | 1981 | 200 |

| Czechoslovakia | T-55 | tank | 1982-1985 | 400 |

| South Africa | G5 155mm | Pipe artillery | 1985-1988 | 200 |

| Hungary | PSZH-D-994 | Personnel carriers | 1981 | 300 |

| United States | Bell 214ST | helicopter | 1987-1988 | 31 |

| United States | Hughes-300 / TH-55 | helicopter | 1984 | 30th |

| United States | MD-500MD Defender | helicopter | 1983 | 30th |

| United States | MD-530F | helicopter | 1985-1986 | 26th |

| People's Republic of China | Xian H-6 | Bomb plane | 1988 | 4th |

| People's Republic of China | F-6 | Fighter plane | 1982-1983 | 40 |

| People's Republic of China | F-7A | Fighter plane | 1983-1987 | 80 |

| People's Republic of China | Type-63 107mm | Rocket launcher | 1984-1988 | 100 |

| People's Republic of China | Type-83 152mm | Pipe artillery | 1988-1989 | 50 |

| People's Republic of China | W-653 / Type-653 | Armored recovery vehicles | 1986-1987 | 25th |

| People's Republic of China | WZ-120 / Type-59 | tank | 1982-1987 | 1000 |

| People's Republic of China | WZ-121 / Type 69 | tank | 1983-1987 | 1500 |

| People's Republic of China | YW 531 | Personnel carriers | 1982-1988 | 650 |

| People's Republic of China | CEIEC-408C | radar | 1986-1988 | 5 |

| People's Republic of China | HN-5A | Anti-aircraft missile | 1986-1987 | 1000 |

| People's Republic of China | HY-2 / SY1A / CSS-N-2 | Ship missile | 1987-1988 | 200 |

List of arms sales to Iran under the Shah

| country | specification | description | delivery | Number pieces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great Britain | Chieftain | tank | 1972-1988 | 800 |

| United States | M60 | tank | 1969-1988 | 460 |

| United States | M47 | tank | until 1978 | 400 |

| United States | M24 | tank | until 1978 | 100 |

| United States | M113 | Armored personnel carriers | until 1978 | 400 |

| United States | McDonnell F-4 | Fighter plane | 1968-1988 | 180 |

| United States | Northrop F-5 | Fighter plane | 1965-1978 | 221 |

| United States | Grumman F-14 | Fighter plane | 1975-1988 | 79 |

| United States | AIM-54 Phoenix | Air-to-air missile | until 1978 | 284 |

| United States | Lockheed C-130 | Transport plane | 1965-1978 | 56 |

| United States | Lockheed P-3 | Maritime patrol | 1973-1978 | 4th |

| United States | Boeing B707 | Tanker aircraft | 1973-1978 | 10 |

| United States | Sikorsky S-65 | Transport helicopter | 1973-1978 | 18th |

| United States | Boeing-Vertol CH-47 | Transport helicopter | 1971-1978 | 16 |

| United States | Bell UH-1 | helicopter | 1972-1988 | 287 |

| United States | Bell AH-1 | helicopter | 1972-1988 | 202 |

| United States | Bell 206 | helicopter | 1968-1988 | 140 |

| Soviet Union | BTR-50 | Armored personnel carriers | until 1978 | 300 |

| Soviet Union | BTR-60 | Armored personnel carriers | until 1978 | 400 |

List of arms sales to the Islamic Republic of Iran

| country | specification | description | delivery | number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Libya | R-17 / SS-1c Scud-B | Surface-to-surface missile | 1985-1986 | 54 |

| North Korea / Soviet Union | R-17 / SS-1c Scud-B | Surface-to-surface missile | from 1987 | > 200 |

| Austria | Gun Howitzer Noricum | gun | 1985-1988 | 140 |

| People's Republic of China | Silkworm | Anti-ship missile | 1987-1988 | ? |

| People's Republic of China | Type 59 | tank | 1982-1988 | 220? |

| United States / Israel | BGM-71 TOW | Anti-tank guided missile | 1985-1986 | 2,515 |

| United States / Israel | MIM-23 HAWK | Anti-aircraft missile | 1985-1986 | 258 |

Result

losses

The war was fateful for both countries, although the information on the number of casualties varies greatly depending on the author and ultimately does not allow an exact estimate. There are sources that speak of 300,000 (Iraq) to 500,000 deaths (Iran), others assume up to a million deaths in total, the most conservative estimate assumes at least 367,000 deaths, 262,000 Iranians and 105,000 Iraqis. However, it is certain that the First Gulf War, along with the Korean War , the Vietnam War , the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan , the civil war in Ethiopia and the civil war in Angola was one of the most costly military actions of the second half of the 20th century. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) registered nearly 40,000 Iranian and more than 67,000 Iraqi prisoners of war throughout the course of the war . The number of missing soldiers with an unknown fate was estimated by the ICRC in 2008, 20 years after the end of the war, at tens of thousands.

War damage and indebtedness

The considerable damage to infrastructure and industry was quantified as follows:

- Iran: $ 644 billion

- Iraq: $ 452 billion

The total oil revenues of both countries, Iran from 1919 to 1988 and Iraq from 1931 to 1988, amounted to 418.5 billion US dollars (Mofid, p. 53). Iraq had a significant debt burden to pay off its former Arab supporters, which also contributed to Saddam Hussein's attack on Kuwait on August 2, 1990. Mofid suspects that “Saddam Hussein assumed that Saudi Arabia and Kuwait would provide further aid” (Mofid, p. 13) and “would grant favorable repayment terms. The 41 states that would have earned from arms deliveries should also participate in the reconstruction. "(Mofid, p. 57)

At the end of the war the borders remained unchanged. Two years later, during the Second Gulf War with the USA, the British and other Western powers and immediately after the conquest of Kuwait, Saddam Hussein recognized Iranian rights over the eastern half of the Shatt al-Arab, which meant recognition of the status quo , to which he had refused approval ten years earlier.

The war was intended to weaken the Islamic Republic of Iran. In retrospect, however, it can be said that the war in particular strengthened the Islamic Republic in its sphere of influence. In the struggle with Iraq, the population stood behind the new rulers, who had previously been highly controversial. The imposition of martial law also made it possible to act more effectively against the internal Iranian opposition. The international isolation of Iran and the resulting lack of supplies and spare parts led to the establishment of its own arms industry , which today can mass-produce numerous, self-developed weapons systems.

Even today, almost 600,000 hectares of land with an estimated 16 million uncleaned mines are left behind from the First Gulf War, which, according to Shirin Ebadi, cost three lives a day.

Memorials

Iraqi President Saddam Hussein had a monument to the victors erected on Parade Street in the capital, Baghdad, in the form of two huge hands with two crossed swords. Steel helmets of Iranian soldiers were attached to the base of the monument. In Iran, the “ Martyrs Cemetery” at the Behescht-e Zahra central cemetery near Tehran is one of the most important memorial sites and is visited by relatives and believers every Friday, the holiday of the Islamic calendar. There is also a war museum at the cemetery, the building of which is covered with martial wall paintings depicting six young soldiers with Kalashnikov rifles in front of their chests and martyrs' headbands.

See also

- Second Gulf War

- Iraq war

- List of Iraqi fighter pilots in the First Gulf War

- List of Iranian fighter pilots in the First Gulf War

- History of Iran since 1979

- History of Iraq # Republic of Iraq

literature

- Henner Fürtig: The Iraqi-Iranian War 1980–1988. In: Bernd Greiner, Christian Th. Müller, Dierk Walter (eds.): Hot wars in the cold war . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-936096-61-9 , pp. 376-407 ( review by H. Hoff , review by I. Küpeli ).

- Dilip Hiro: The Longest War . The Iran-Iraq Military Conflict. New York: Routledge Chapman & Hall, Inc., 1991, ISBN 0-415-90407-2 .

- Peter Hünseler : Iraq and its conflict with Iran. Development, domestic political determinants and perspectives (= working papers on international politics . 22). Europa-Union-Verlag, Bonn 1982, ISBN 3-7713-0187-4 .

- Williamson Murray and Kevin M. Woods: The Iran-Iraq War. A Military and Strategic History. Cambridge University Press 2014, ISBN 978-1-107-06229-0 .

Web links

- First Gulf War in the War Archive of the University of Hamburg (Department of Social Sciences)

- The First Gulf War (school presentation)

- Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988) (English)

- Resolution 598 (1987)

Individual evidence

- ^ Dilip Hiro, p. 116

- ↑ Erhard Franz : Kurds and Kurdentum - Contemporary history of a people and its national movements , pages 50 and 56f. German Orient Institute, Hamburg 1986

- ^ The Working Group on Research into the Causes of War (AKUF) ( Memento of January 27, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) classifies the war as type C2 ( Memento of January 27, 2006 in the Internet Archive ), as an interstate war without outside participation.

- ↑ The Orient Pact (Treaty of Saadabad) from July 8, 1937 (in French. Language) (PDF)

- ^ Tariq Aziz : The Iraqi-Iranian Conflict - Questions and Discussions , pages 11, 14 and 85f. Dar Al-Ma'mun, Baghdad 1981

- ^ Dilip Hiro, p. 38

- ↑ Michael Ploetz, Tim Szatkowski: Files on the Foreign Policy of the Federal Republic of Germany 1979 Vol. I: January to June 30, 1979. R. Oldenbourg Verlag Munich, 2010, p. 898.

- ↑ Michael Ploetz, Tim Szatkowski: Files on the Foreign Policy of the Federal Republic of Germany 1979 Vol. II: July 1 to December 31, 1979. R. Oldenbourg Verlag Munich, 2010, p. 985.

- ↑ a b c Fariborz Riyahi: Ayatollah Khomeini . Ullstein, 1986, ISBN 3-548-27540-0 , p. 117.

- ↑ 1980: SAS rescue ends Iran embassy siege. BBC , accessed September 2, 2014 .

- ↑ Anja Malanowski & Beate Seel: Chronology of War . P. 81.

- ↑ Kenneth Pollack: Arabs at War , Lincoln, 2002, p. 184

- ↑ a b c d e Henner Fürtig: The Iraqi-Iranian War . Akademie Verlag GmbH, 1992, ISBN 3-05-001905-0 .

- ^ The New York Times, September 23, 1980.

- ↑ Shaul Bakhash: The Reign of the Ayatollahs: Iran and the Islamic Revolution. IB Tauris & Co Ltd, 1985, ISBN 1-85043-003-9 , p. 127.

- ↑ Staudenmaier: Iran – Iraq . 1984, p. 228.

- ↑ Stephen C. Pelletiere: The Iran-Iraq War (Chaos in a Vacuum), Greenwood 1992, ISBN 978-0-275-93843-7 , p. 41.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Drögemüller: Iranisches Tagebuch. 5 years of revolution . 1983, ISBN 3-922611-51-6 , p. 334.

- ↑ Christopher de Bellaigue: In the rose garden of the martyrs. A portrait of Iran. From the English by Sigrid Langhaeuser, Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2006 (English original edition: London 2004), p. 208 f.

- ^ Daniel Krüger: The USA and Saddam Hussein, Grin Verlag 2009, ISBN 978-3-640-49826-0 , p. 39.

- ^ A b Adel S. Elias, Hans Hielscher: Whoever does not fight will be shot . In: Der Spiegel . No. 23 , 1984, pp. 110 ( online - 4 June 1984 ).

- ^ Die ZEIT, March 23, 1985, No. 13 ( Memento of January 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Günther Kirchberger: Knaurs Weltspiegel '87 , pages 286f and 290.Droemer Knaur , Munich 1986

- ↑ boeing.com awacs ( memento of October 29, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) accessed on December 31, 2012

- ^ Daniel Krüger: The USA and Saddam Hussein, Grin Verlag 2009, ISBN 978-3-640-49826-0 , p. 40.

- ↑ To “Kerbela 4” see also Christopher de Bellaigue: In the rose garden of the martyrs. A portrait of Iran. From the English by Sigrid Langhaeuser, Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2006 (English original edition: London 2004), pp. 241–247

- ↑ Munzinger Archive / Internationales Handbuch - Zeitarchiv 18/88, page 16 (Iraq Chronicle 1986). Ravensburg 1988

- ↑ Gustav Fochler-Hauke (Ed.): Der Fischer Weltalmanach 1988 , pages 301 and 303. Frankfurt / Main 1987

- ↑ Cameron R. Hume: The United Nations, Iran, and Iraq - How Peacemaking Changed , 87. Indiana University Press, Georgetown 1994

- ^ Efraim Karsh: The Iran-Iraq War , pages 9 and 55f. The Rosen Publishing Group, New York 2009

- ↑ Munzinger Archive / Internationales Handbuch - Zeitarchiv 18/88, page 17 (Irak Chronik 1987). Ravensburg 1988

- ↑ Iran Chamber Society: History of Iran, Iran-Iraq War 1980–1988

- ^ Bryan R. Gibson: Covert Relationship - American Foreign Policy, Intelligence, and the Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988 , pp. 180-185. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2010

- ↑ a b c Efraim Karsh: The Iran-Iraq War , page 9. The Rosen Publishing Group, New York 2009

- ↑ Munzinger Archive / Internationales Handbuch - Zeitarchiv 18/88, page 17 (Irak Chronik 1987). Ravensburg 1988

- ↑ Bryan R. Gibson: Covert Relationship - American Foreign Policy, Intelligence, and the Iran-Iraq War, 1980–1988 , 189. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2010

- ↑ a b c Bryan R. Gibson: Covert Relationship - American Foreign Policy, Intelligence, and the Iran-Iraq War, 1980–1988 , page 190. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2010

- ^ Efraim Karsh: The Iran-Iraq War , p.9. The Rosen Publishing Group, New York 2009

- ↑ Munzinger Archive / Internationales Handbuch - Zeitarchiv 18/88, page 17f (Iraq Chronicle 1987). Ravensburg 1988

- ↑ Iran Chamber Society: History of Iran, Iran-Iraq War 1980–1988

- ↑ Munzinger Archive / Internationales Handbuch - Zeitarchiv 18/88, page 21 (Irak Chronik 1987). Ravensburg 1988

- ^ Arabian Peninsula & Persian Gulf Database: I Persian Gulf War: Iraqi Invasion of Iran, September 1980

- ↑ Kenneth Pollack: Arabs at War , Lincoln, 2002, pp. 184-186

- ^ Helge Timmerberg: Bombs on Tehran. In: Orient Exquisite . Wieser, 2004, ISBN 3-85129-426-2 , p. 85.

- ↑ Farhang Rajaee: The Iran-Iraq War. University Press 1993, ISBN 978-0-8130-1176-9 , p. 38.

- ^ Dilip Hiro, page 183

- ↑ a b c umich.edu (PDF; 8.5 MB) Detailed list of all Iraqi R-17 missiles based on the serial number and their use, accessed on January 8, 2013

- ↑ Yearbook of the United Nations: 41, ISBN 978-0-7923-1613-8 , p. 221.

- ↑ a b From 1987 onwards, R-17s were supplied by North Korea under the designation Hwasong-5 .

- ↑ Center of Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Anthony H. Cordesman, October 2000, page 19 ( Memento of July 10, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 220 kB)

- ↑ Saddam Hussein was upset that Iran was able to hit Baghdad, but he was not able to hit Tehran.

- ↑ Guy Perrimond Guy: The Threat of Theater Ballistic Missiles, 2002 ( Memento of October 16, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 975 kB) accessed on January 3, 2013

- ^ Compare: Al Hussein missile , article on the English language Wikipedia

- ↑ The Iraqi attempt to acquire SS-12 Scaleboard was rejected.

- ↑ a b Farhang Rajaee: The Iran-Iraq War. University Press 1993, ISBN 978-0-8130-1176-9 , p. 37.

- ↑ a b Bahman Nirumand: War, war, until victory. In: Iran-Iraq. 1987. page 95

- ^ Child-Soldier Treaty Has Wide Support. The New York Times on December 19, 1988, accessed February 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Freedom of Information Center: US Corps In Iraq ( Memento January 19, 2003 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ UNMOVIC: Twenty-fifth quarterly report on the activities of the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission in accordance with paragraph 12 of Security Council resolution 1284 (1999) (PDF; 76 kB)

- ↑ globalsecurity.org Iraq Survey Group Final Report , accessed January 10, 2013

- ↑ Message d. Islamic Republic of Iran, press and Culture Department (Ed.): Iran and the Islamic Republic: On the Iraqi-Iranian War . Bonn 1981, p. 41.

- ↑ Stockholm International Peace Research Institute: CHEMICAL WARFARE IN THE IRAQ-IRAN WAR ( Memento of May 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ According to Iranian sources, see: Farhang Rajaee: The Iran-Iraq War. University Press 1993, ISBN 978-0-8130-1176-9 , p. 34.

- ↑ This coincides with Western statements that assume 50,000 wounded and 5,000 killed soldiers by Iraqi chemical weapons operations. See: Oliver Thränert: Iran and the spread of NBC weapons , Science and Politics Foundation, Berlin 2003, ISSN 1611-6372 .

- ↑ UN-SC S 16433, March 26, 1984 (PDF; 2.2 MB)

- ↑ gwu.edu (PDF; 70 kB) US State Department to the Iraqi State Secretary , March 1984

- ↑ RESOLUTION 582 (1986) (PDF; 157 kB)

- ↑ RESOLUTION 612 (1988)

- ↑ Nikki R. Keddie: Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution , Yale University 2006, ISBN 978-0-300-12105-6 , p. 369.

- ↑ a b Henner Fürtig: Brief history of Iraq. From the foundation in 1921 to the present . Beck, 2003, ISBN 3-406-49464-1 , p. 114.

- ↑ Manfred Schelzel: Maritime Economy . 1985. p. 122

- ^ J. Korschunow: Persian Gulf . 1987, p. 9.

- ↑ Five million keys to paradise . In: Der Spiegel . No. 1 , 1988 ( online ).

- ↑ Yearbook of the United Nations: 41 (1987), ISBN 978-0-7923-1613-8 , p. 223.

- ↑ http://unscr.com/files/1987/00598.pdf

- ↑ Resolution 582 of the UN Security Council of February 24, 1986

- ↑ Further Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 598. (PDF; 116 kB) United Nations, December 9, 1991, p. 1 , accessed on September 3, 2014 .

- ↑ Further Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 598. (PDF; 6 kB) United Nations, December 9, 1991, p. 2 , accessed on September 3, 2014 .

- ↑ Further Report of the Secretary-General on the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 598. (PDF; 3 kB) United Nations, December 9, 1991, p. 3 , accessed on September 3, 2014 .

- ↑ The Economist, April 19-25. September 1987

- ↑ http://www.country-data.com/cgi-bin/query/r-2549.html

- ↑ Michael Flitner: War as a business, arms exports in Iran and Iraq . P.56.

- ↑ Michael Lüders: Armageddon in the Orient: How the Saudi Connection targets Iran . 3. Edition. Verlag CHBeck, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-406-72791-7 , pp. 52 .

- ^ Trita Parsi, Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran, and the United States , Yale University, 2007, passim ; Thomas L. Friedman, Isreael Aide Traces US-Iran Dealings , in: New York Times , November 22, 1986 : “A senior Israeli official said today that the sale of American arms to Iran grew out of Israeli links with the Khomeini Government dating to 1979 "; Jane Hunter, Special Report: Israeli Arms Sales to Iran in: Washington's Report on Middle East Affairs , November 1986, p. 2 : Israel delivered weapons to Iran between 1980 and 1986.

- ^ Arms Transfers Database, TIV of arms imports to Iraq, 1980–1988 , Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

- ↑ Tom Cooper : airspacemag.com Persian Cats, accessed December 21, 2012

- ^ Ulrich Gehrke: Iran. Defense and Security . Ed. Erdmann, Stuttgart 1976, ISBN 3-522-64050-0 , p. 259 ff.

- ↑ fas.org missile / shahab-1.Retrieved December 31, 2012

- ↑ csis.org: Iran's Missiles and Possible Delivery Systems, 2006 (PDF; 633 kB) accessed on December 31, 2012

- ↑ Iran receives 200 Scud-B missiles . In: Der Spiegel . No. 17 , 1987 ( online - 20 April 1987 ).

- ↑ Noricum scandal. In: dasrotewien.at - Web dictionary of the Viennese social democracy. SPÖ Vienna (Ed.)

- ↑ a b See: Iran-Contra-Affair

- ^ Dilip Hiro, The Longest War: The Iran-Iraq Military Conflict. New York: Routledge Chapman & Hall, Inc., 1991. p. 250

- ^ Twenty years after the end of the Iran-Iraq war, tens of thousands of combatants still unaccounted for . Communication from the International Committee of the Red Cross, October 16, 2008 (accessed October 17, 2008)

- ↑ a b c Kamran Mofid: Economic Reconstruction of Iraq. In: Third World Quarterly . London, 1990.

- ↑ Shahram Rafizadeh: 16 Million Mines Still Awaiting Victims ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , November 22, 2006. (English)