International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement includes the International Committee of the Red Cross ( ICRC ) (Engl. Officially International Committee of the Red Cross ( ICRC )), the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (Engl. Official International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies ( IFRC )) and the national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. All of these organizations are legally independent of one another and are linked within the movement by common principles, goals, symbols, statutes and organs. The movement's mission, which is equally valid worldwide - independent of state institutions and on the basis of voluntary aid - is the protection of life, health and dignity as well as the reduction of the suffering of people in need regardless of nationality and origin or religious, ideological or political views of those affected and those providing aid.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), founded at the suggestion of Henry Dunant in 1863, consists of up to 25 Swiss citizens, is the oldest international medical aid organization and the only organization that is covered by international humanitarian law and named as its controlling body. It is the oldest organization of the movement and, alongside the Holy See and the Sovereign Order of Malta, one of the few original non-governmental subjects of international law . Its exclusively humanitarian mission, based on the principles of impartiality, neutrality and independence, is to protect the life and dignity of the victims of war and internal conflict .

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies , the successor organization to the League of Red Cross Societies established in 1919 , coordinates the cooperation between the national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies within the movement and provides support in the establishment of new national societies. At the international level, it leads and organizes, in cooperation with the national societies, relief missions after non-war-related emergencies such as natural disasters and epidemics .

The national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies are organizations in almost every country in the world, which are active in their home country in accordance with international humanitarian law and the statutes of the international movement and support the work of the ICRC and the Federation. Her most important tasks in her home countries are disaster relief and the dissemination of the Geneva Conventions . Within the scope of their possibilities, they can also perform other social and humanitarian tasks that are not directly prescribed by international law or the principles of the movement. In many countries this includes, for example, the blood donation system and the ambulance service as well as care for the elderly and other areas of social work .

From its founding in 1928 as an umbrella organization of the ICRC and the Federation to its renaming in 1986, the official name of the movement was the International Red Cross . However, this term, which is still widely used today, and the abbreviation IRK resulting from it, should no longer be used if possible, as they can lead to problems in differentiating between the ICRC and the federation in the public perception.

story

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

Solferino, Henry Dunant and the founding of the ICRC

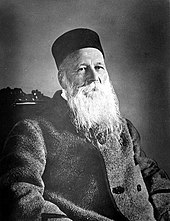

Up until the middle of the 19th century there was no even remotely systematic war nursing, no secure facilities for accommodating and treating the wounded, let alone preventive care through the provision of auxiliary workers in sufficient numbers and with appropriate equipment and training. In 1859 the Swiss businessman Henry Dunant traveled to Italy to meet with the French Emperor Napoléon III. to talk about his problems with obtaining land concessions in French-occupied Algeria . On June 24, 1859, near the small town of Solferino, he witnessed the battle of Solferino and San Martino , in the course of which around 6,000 soldiers were killed and around 25,000 wounded in a single day. The completely inadequate medical care and support as well as the suffering of the wounded soldiers horrified him so much that he completely forgot the original purpose of his trip and devoted himself to caring for the wounded and organizing relief measures for several days. Under the influence of these experiences he wrote a book which he published in 1862 under the title A Memory of Solferino at his own expense and sent to leading political and military personalities throughout Europe. In addition to a very haunting description of what he had experienced in 1859, in this book he encouraged the formation of voluntary aid organizations that were supposed to prepare in peacetime to help the wounded in war. Furthermore, he called for the conclusion of contracts in which the neutrality and protection of the war wounded and the people caring for them, as well as all facilities established for them, should be ensured.

In his hometown of Geneva , Henry Dunant and four other citizens - the lawyer Gustave Moynier , the doctors Louis Appia and Théodore Maunoir and the Army General Guillaume-Henri Dufour - founded a committee of five as a commission of the Geneva Public Benefit Society on February 9, 1863 to prepare one international conference to implement his ideas. Just eight days later, the five founding members decided to rename the commission to the International Committee of Aid Societies for the Care of Wounded . From October 26th to 29th of the same year, at the suggestion of the committee, an international conference was held in Geneva “to discuss the means by which one could remedy the inadequacy of the medical services in the field”. A total of 36 people took part in this conference: 18 official delegates from the governments of their respective countries, six delegates from various clubs and associations, seven unofficial foreign participants and the five members of the International Committee. The federal states represented by official delegates at this conference were Baden , Bavaria , France , Great Britain , Hanover , Hessen-Darmstadt , Italy , the Netherlands , Austria , Prussia , Russia , Saxony , Sweden and Spain . The resolutions and demands of this conference, which were adopted in the form of resolutions on October 29, 1863, included:

- the establishment of national aid societies for war wounded

- the neutrality of the wounded

- sending volunteer nurses to the battlefield to provide assistance

- the organization and implementation of further international conferences

- the introduction of an identification and protection symbol in the form of a white armband with a red cross

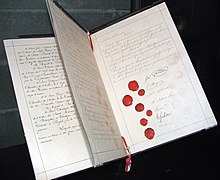

Just one year later, at the invitation of the Swiss government, a diplomatic conference was held in all European countries as well as the United States of America, Brazil and Mexico, attended by 26 delegates from 16 countries. On August 22, 1864, during this conference, the first Geneva Convention "Regarding the Alleviation of the Lot of Military Personnel Wounded in the Field Service" was signed by representatives of twelve states. In ten articles of this convention, the proposals for the protection and neutralization of the wounded, the auxiliary personnel and the corresponding facilities were bindingly laid down. Article 1 of this convention fundamentally stipulates that “all military personnel and other persons serving in the army who are wounded or sick, regardless of nationality, should be respected and cared for by the warring party in whose hands they are”.

At the end of 1863, the Württemberg Medical Association was founded in Stuttgart , followed shortly afterwards by the Association for the Care of Wounded Warriors in the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg and other companies founded in Belgium , Prussia , Denmark , France and Spain in 1864 .

1864 to 1914

The organization experienced its first practical test in the German-Danish War : On April 16, 1864, assistants and, with Louis Appia and the Dutch captain Charles van de Velde , also official delegates took part in a war under the sign of the Red Cross at the Düppeler Schanzen part. A good two months earlier, after the Battle of Oeversee, the first field hospital had been set up under the banner of the Red Cross. In 1866 the Red Cross became active on the battlefield near Langensalza .

In 1867 the first International Red Cross Conference took place with the participation of representatives from nine governments, 16 national Red Cross societies and the International Committee. In the same year, Henry Dunant had to declare his bankruptcy and leave Geneva due to the desperate course of his business in Algeria. After Gustave Moynier had taken over the chairmanship of the International Committee in 1864, Henry Dunant was now completely expelled from the committee. In the years that followed, national Red Cross societies were founded in almost all European countries.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 impressively demonstrated their necessity. Prussia had a Red Cross Society well equipped with personnel and material, which worked closely with the Prussian army in organizational terms. Because of this, the number of Prussian soldiers who died of illness or injury was below the number who died in the field. On the other hand, France only had an inadequately prepared Red Cross Society, with the result that on the French side the number of soldiers who died from illness or injury was three times higher than the number of soldiers who died.

The French Eastern Army , which had been pushed out in February 1871 , was interned by Switzerland. The internment, food and medical care of the 87,000 soldiers of the "Bourbaki Army" contributed to the self-confidence and identity of the young Swiss federal state. The war was also a test for the International Committee of Aid Societies for the Care of the Wound , founded in 1864 , which had few financial resources but could count on many volunteers.

In this war, other Red Cross societies such as those of Russia, Switzerland, Ireland and Luxembourg also participated for the first time by sending doctors and paramedics to a larger extent in the medical service. Clara Barton , who later became the founder of the American Red Cross, received the Iron Cross from Kaiser Wilhelm I for her work in this war . In the wake of the war, the International Red Cross Conference planned for Vienna in 1873 did not take place, and it was not until 1888 that such a conference was held in Geneva again.

In 1876 the International Committee was given the name International Committee of the Red Cross (French Comité international de la Croix-Rouge , CICR - English International Committee of the Red Cross , ICRC), which is still valid today . Two years later, the ICRC and a number of national Red Cross societies first started helping civilians when, at the end of the Balkan crisis in 1878 , the Turkish Red Crescent Society , which had only recently been founded , appealed to the committee for support in caring for refugees . Three years later, the American Red Cross was founded in the United States on the initiative of Clara Barton. During the Spanish-American War in 1898, the three ships Moynier , Red Cross and State of Texas were used for the first time in an armed conflict at sea under the flag of the Red Cross.

By the turn of the century, more and more states signed the Geneva Convention and largely respected it in armed conflicts. In 1901, Henry Dunant, together with the French pacifist Frédéric Passy , received the first ever Nobel Peace Prize . The congratulations that the committee sent on the occasion of the award ceremony meant for him, after 34 years, the late rehabilitation and explicit recognition of his services for the establishment of the Red Cross. Henry Dunant died nine years later, two months after Gustave Moynier.

In 1906 the First Geneva Convention of 1864 was revised for the first time. Just before the start of World War I in 1914, fifty years after the First Geneva Convention was adopted, there were 45 national societies. In addition to companies in almost all European countries and the USA, there were other companies in Central and South America (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Mexico, Peru, El Salvador, Uruguay, Venezuela), Asia (China, Japan, Korea, Siam) and Africa (Republic of South Africa).

The ICRC during the First World War

The First World War presented the ICRC with great challenges that it could only overcome in cooperation with the national Red Cross societies. Red Cross nurses from the USA and Japan were also deployed to support the medical services in the European countries concerned. On October 15, 1914, immediately after the start of the war, the ICRC set up its International Central Office for Prisoners of War , which by the end of 1914 employed around 1,200 mostly volunteer workers, including the French writer and pacifist Romain Rolland as one of the first . When he received the Nobel Prize in Literature for 1915, he donated half of the prize money to the central office. About two-thirds of the volunteers, however, were young women . Some of them - such as Marguerite van Berchem , Marguerite Cramer and Suzanne Ferrière - rose to leading positions and thus contributed to paving the way for equal rights for women in an organization whose executive bodies had previously been exclusively made up of men.

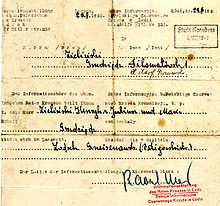

From 1916 to 1919 the central office was housed in the Musée Rath . In the course of the entire war, the central office sent around 20 million letters and messages, almost 1.9 million parcels and donations of around 18 million Swiss francs to prisoners of war from all countries involved. Furthermore, through the mediation of the central office, around 200,000 prisoners were exchanged. The index of the central office, which was created between 1914 and 1923, contains around seven million index cards. In around two million cases it led to the identification of prisoners and thus to contact between the prisoners and their relatives. The entire file can now be viewed on permanent loan from the ICRC in the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum in Geneva, although the ICRC still reserves the right to inspect it.

The ICRC monitored compliance with the Geneva Convention in the version of 1906 throughout the war and passed on complaints about violations to the participating states. The ICRC also protested against the use of chemical warfare agents , which were first used in the First World War. Without a mandate from the Geneva Convention, the ICRC also stood up for the civilian population affected by the war, especially in occupied territories, where the ICRC was able to fall back on the Hague Land Warfare Regulations as a legally binding agreement. The activities of the ICRC in relation to prisoners of war were also based on the Hague Land Warfare Regulations , including visits to prisoner-of-war camps in addition to the tracing service and exchange of information already described. A total of 524 camps across Europe were visited by 41 ICRC delegates during the war.

Between 1916 and 1918 the ICRC published several postcards depicting the camps visited by its delegates. For this purpose, pictures were selected which showed the prisoners doing everyday activities such as distributing mail. The aim of the publication of these cards was to give hope and reassurance to the relatives of the prisoners. After the end of the war, the ICRC organized the repatriation of around 420,000 prisoners of war to their home countries. For its activities during the First World War, the ICRC received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1917, the only one awarded in the war years from 1914 to 1918.

The further repatriation of the prisoners was taken over from 1920 by the newly founded League of Nations under the responsibility of its High Commissioner for the repatriation of the prisoners of war Fridtjof Nansen . His mandate was later expanded to support and care for war refugees and displaced persons. To support these activities, he elected two ICRC delegates to be his deputies.

In 1923 the committee, which had only allowed members of Geneva to be members since its inception, decided to lift this stipulation in favor of a restriction to Swiss nationals.

As a direct consequence of the First World War with regard to international humanitarian law, the Geneva Protocol of 1925 banned the use of asphyxiating and poisonous gases as well as bacterial warfare agents for warfare. Furthermore, the First Geneva Convention was revised again in 1929 and a new agreement on the treatment of prisoners of war was adopted. The events of the First World War and the corresponding activities of the ICRC resulted in a clear appreciation of the committee's reputation and authority over the international community and an expansion of its competencies.

At the International Red Cross Conference in 1934, a draft for a convention for the protection of the civilian population during a war was adopted for the first time. Most governments did not show enough interest in implementation that a diplomatic conference to adopt this convention did not take place before the start of World War II .

The ICRC and the Second World War

The activities of the ICRC during the Second World War were based on the Geneva Conventions in the version of 1929. As in the First World War, the ICRC's activities during the Second World War focused on monitoring the POW camps, helping the civilian population and exchanging information on prisoners and missing persons Persons. During the entire course of the war there were 12,750 visits to prisoner-of-war camps in 41 countries by 179 delegates. The Central Information Center for POWs employed around 3,000 people during this war. Your file consisted of approx. 45 million cards and approx. 120 million messages were sent. A major problem for the work of the ICRC was the DC circuit of the German Red Cross in the era of National Socialism and the associated severe restrictions in the cooperation with the DRC in relation to the deportation of Jews from Germany and the mass murder in the extermination and concentration camps . The fact that the Soviet Union and Japan, two main powers of the war, had not acceded to the 1929 Geneva Convention “On the Treatment of Prisoners of War” made matters even more difficult.

During the entire war, the ICRC did not succeed in achieving equality between the people interned in the concentration camps and prisoners of war among the National Socialist rulers. Due to the fear that by continuing to insist on corresponding demands, its activities for prisoners of war and thus its mission, which is legitimized under international law, would be jeopardized, the ICRC refrained from further efforts in this regard. For the same reason, and because of a possible threat to its neutrality, the ICRC took hesitant and inadequate steps with the Allies regarding its knowledge of the existence of the extermination camps and the deportation of the Jewish population. Another reason was the influence of the Swiss government on the committee at the time and the resulting subordination of the ICRC to government guidelines that corresponded to Switzerland's security interests. Such was Philipp Etter , the Swiss Federal Council in Department of the Interior from 1934 to 1959 and President in 1939, 1942, 1947 and 1953, at the time, also a member of the ICRC. An important goal of Swiss politics during the war was to preserve the neutrality and sovereignty of Switzerland under all circumstances, which was at times completely surrounded by the Axis powers. The resulting avoidance of all actions that Germany or its allies could have snubbed also affected the activities of the ICRC and was viewed by the victorious powers as illegitimate cooperation with the Nazis after the end of the war.

It was not until November 1943 that the ICRC was allowed to send parcels to those concentration camp inmates whose names and whereabouts were known to the committee and who were not subject to stricter detention conditions. Thanks to the acknowledgments of receipt, which were often signed by several other inmates in addition to the recipients, the ICRC succeeded in registering around 105,000 people in the camps and sending a total of 1.1 million parcels, mainly to the Dachau , Buchenwald and Ravensbrück camps and Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen . On March 12, 1945, the then ICRC President Carl Burckhardt received a promise from SS General Ernst Kaltenbrunner that ICRC delegates would be granted access to the concentration camps. However, this was subject to the condition that these delegates remained in the camps until the end of the war. Ten delegates, among them Louis Häfliger ( Mauthausen ), Paul Dunant ( Theresienstadt ) and Victor Maurer ( Dachau ) declared themselves ready for such a mission. Through his personal efforts, Louis Häfliger prevented the Mauthausen camp from being blown up and thus saved the lives of thousands of prisoners. He was condemned by the ICRC for his unauthorized actions and only rehabilitated in 1990 by the then President Cornelio Sommaruga . The activities of the ICRC delegate Friedrich Born for the Jewish population in Hungary are also outstanding from the time of the Second World War . Through his efforts, he saved the lives of around 11,000 to 15,000 people and was posthumously accepted into the Israeli Holocaust memorial at Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations on June 5, 1987 . Another well-known delegate of the ICRC in World War II was the Geneva doctor Marcel Junod , whose experiences can be read in his book Fighters on Both Sides of the Front .

In 1944 the ICRC again received the Nobel Peace Prize, which had not been awarded since the beginning of the war. After the end of the war, the ICRC, in cooperation with various national Red Cross societies, organized aid measures in the countries affected by the war. In Germany, this was mainly done by the Swedish Red Cross under the direction of Folke Bernadotte . Other extensive relief efforts by national societies were Operation Shamrock of the Irish Red Cross and the Children's Aid of the Swiss Red Cross . The Jewish escape aid company Beriha was also supported by the ICRC in rescuing around 5000 Jews from Poland to Romania in January 1945. In 1948 the ICRC published a “Report of the International Committee of the Red Cross on its work during the Second World War (September 1, 1939 - June 30, 1947)”. The ICRC archive has been open to the public since January 17, 1996 .

The ICRC after the Second World War

On August 12, 1949, fundamental revisions of the two existing conventions were adopted, which have since been referred to as the Geneva Conventions I and III. Two new agreements, the Geneva Agreement II "to improve the lot of the wounded, sick and shipwrecked by the armed forces at sea" and, as the most important consequence of the Second World War, the Geneva Agreement IV "on the protection of civilians in times of war", were also expanded the protection of international humanitarian law for other groups of people.

The two additional protocols dated June 8, 1977 brought further significant additions in several areas. On the one hand, both protocols for the first time also integrated rules for permissible means and methods of warfare and thus regulations for dealing with the people involved in the fighting, the so-called combatants the context of the Geneva Conventions. Secondly, Protocol II realized one of the longest pursued goals of the ICRC: the extension of the applicability of international humanitarian law to situations in non-international, armed conflicts such as civil wars. Today the four Geneva Conventions and their two additional protocols comprise over 600 articles.

To mark the centenary of its founding, the ICRC was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for the third time in 1963, this time together with the League. Despite this recognition and the success of the International Committee in the further development of international humanitarian law, its activities during the Cold War conflicts were severely restricted by the largely negative attitude of the communist states, which was based on fundamental doubts about the neutrality of the committee. The ICRC could not become active in either the Indochina War or the Vietnam War , as this was strictly rejected by the governments of the respective countries. Only the joint aid mission with UNICEF in Cambodia after the invasion of Vietnam in 1978/1979 improved relations between the ICRC and the communist community of states. In the conflicts between the Arab states and Israel and between India and Pakistan , however, the work of the committee was not affected by such problems. In the Biafra war from 1967 to 1970 for the independence of the Biafra area from Nigeria , difficulties emerged within the management level of the committee with regard to operational activities and cooperation with the national Red Cross societies on site. French doctors around Bernard Kouchner , who were dissatisfied with the restrictions that had resulted from the principle of neutrality for the work of the committee and the French Red Cross, also founded the aid organization Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) in 1971 . Within the ICRC, the events of the conflict in Biafra led to a fundamental reorganization of the distribution of roles between the members of the committee and the president on the one hand and the employees on the other. In the area of practical work in particular, the committee's employees were given significantly more skills and influence.

The Falklands War between Argentina and Great Britain in 1982 was characterized on the part of both conflicting parties by exemplary cooperation with the ICRC and almost complete compliance with the provisions of international humanitarian law. This enabled the committee to register the approximately 11,700 prisoners of war in this conflict in accordance with the Geneva Conventions and to care for them appropriately. With regard to the care of the wounded, the Falklands War represented by far the most extensive application of the corresponding Geneva Convention since its conclusion in 1949 due to the naval warfare. In addition, the committee succeeded in a written agreement between the two conflicting parties to establish a neutral medical and safety zone for civilians in the area to reach the church of the Falkland capital Stanley . Nine years after the end of the conflict, through mediation by the ICRC, around 300 relatives visited the graves of fallen Argentine soldiers in the Falkland Islands, organized by the committee.

The General Assembly of the United Nations (UN) decided on 16 October 1990 the ICRC as an observer (Engl. Observer ) to their meetings and the meetings of its committees to invite. The corresponding resolution (A / RES / 45/6) was tabled by 138 member countries and adopted without a vote at the 31st plenary session. For historical reasons - with reference to the Battle of Solferino - the resolution was presented by Vieri Traxler, the then UN ambassador of the Republic of Italy. With this decision, observer status in the UN General Assembly was granted to a private organization for the first time. An agreement signed on March 19, 1993 with the Swiss Federal Council guarantees the ICRC full independence and freedom of action in its activities in Switzerland; the inviolability of its premises, archives and other documents; extensive legal immunity for the committee and its members, delegates and other employees; exemption from all direct and indirect taxes and other fees at federal, cantonal or local level; free customs and payments; Benefits with regard to its communication that are comparable to those for international organizations and foreign diplomatic missions based in Switzerland; as well as extensive relief for its members, delegates and employees when entering and leaving the country.

Since 1993, people of other nationalities than Swiss have been able to work for the ICRC, both on site at the headquarters in Geneva and as delegates on missions abroad. The proportion of employees without Swiss citizenship has risen continuously since then and is currently around 35 percent. For the ICRC, however, the period since 1990 has also been marked by a series of tragic events. More delegates than ever before in the history of the committee lost their lives in their missions. This trend is primarily due to the increase in the number of local and often internal conflicts as well as a lack of respect on the part of the parties involved for the provisions of the Geneva Conventions and their symbols.

President of the ICRC

The current President of the ICRC since July 2012 has been Peter Maurer , who took over from Jakob Kellenberger . Christine Beerli has been the vice-president since January 2008 . Previous presidents of the ICRC were:

- from 1863 to 1864: Guillaume-Henri Dufour

- from 1864 to 1910: Gustave Moynier

- from 1910 to 1928: Gustave Ador

- from 1928 to 1944: Max Huber

- from 1945 to 1948: Carl Jacob Burckhardt

- from 1948 to 1955: Paul Ruegger

- from 1955 to 1964: Léopold Boissier

- from 1964 to 1969: Samuel Gonard

- from 1969 to 1973: Marcel Naville

- from 1973 to 1976: Eric Martin

- from 1976 to 1987: Alexandre Hay

- from 1987 to 1999: Cornelio Sommaruga

- from 2000 to 2012: Jakob Kellenberger

- since 2012: Peter Maurer

A detailed overview with life data, biographical information and important events during the respective term of office can be found in the list of presidents of the International Committee of the Red Cross .

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

From the foundation to 1945

On May 5, 1919, the National Red Cross Societies of Great Britain, France, Italy, Japan and the USA founded the League of Red Cross Societies in Paris at the suggestion of the then President of the American Red Cross, Henry P. Davison . The expansion of the Red Cross activities beyond the strict mission of the ICRC to include aid for victims of non-war-related emergencies (such as after technical accidents and natural disasters), which was to be the task of the league at the international level, also happened on the initiative of the American Red Cross . Since it was founded, it has been active with relief operations even in peacetime, an idea that went back to its founder Clara Barton.

The founding of the league, another internationally active Red Cross organization alongside the ICRC, was initially controversial for several reasons. On the one hand, the ICRC raised fears, in some cases justified, of competition between the two organizations. The creation of the League was seen as an attempt to challenge the Committee's leadership and to delegate most of its functions and powers to a multilateral institution. In the opinion of the leadership of the American Red Cross, the ICRC was too cautious in its action and not influential enough in terms of its international importance. On the other hand, only national societies from states of the Entente or with their allied or associated countries were involved in the founding of the league . The statutes of the league, originally adopted in May 1919, also granted the five companies involved in its founding a special status and, at the instigation of Henry P. Davison, the right to use the national Red Cross societies of the Central Powers Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria and the Permanently exclude Turkey and the Russian Red Cross. However, this passage contradicted the Red Cross principles of universality and equality between all national societies. The establishment of the League of Nations also played a role in the founding of the League. So find z. B. in Art. 25 of the League of Nations of 1919 as an obligation of states to promote and encourage the establishment and cooperation of recognized voluntary national organizations of the Red Cross for the improvement of health, the prevention of diseases and the alleviation of suffering in the world.

The first relief operation organized by the league immediately after it was founded was to take care of those affected by a typhus epidemic and famine in Poland. In the first five years after its founding, the league issued 47 appeals for donations for aid campaigns in 34 countries. In this way, aid worth around 685 million Swiss francs reached victims of famine in Russia, Germany and Albania, earthquakes in Chile, Persia, Japan, Colombia, Ecuador, Costa Rica and Turkey and refugees in Greece and Turkey. Another important concern of the league was the support of the national societies in the creation of youth sections. The league's first major disaster response was the 1923 earthquake in Japan, which killed around 200,000 people. Through the agency of the league, the Japanese Red Cross received aid from other national societies with a total value of approximately 100 million dollars.

With the use of the league together with the ICRC in the Russian Civil War (1917-1922), the movement became active for the first time in an internal conflict. While the league, with the support of more than 25 national societies, primarily took on the distribution of aid and supplies to the starving civilian population affected by epidemics, the ICRC, through its neutrality, supported the Russian and later the Soviet Red Cross in its activities with the conflicting parties. To coordinate the activities between the ICRC and the league and to settle the rivalries between the two organizations, the International Red Cross was founded in 1928 as the umbrella organization of both organizations. An International Council acted as the leading body of the IRK. The tasks of the council were later by the Permanent Commission (Engl. Standing Commission adopted). In the same year, joint statutes of the Red Cross movement were adopted for the first time, which described the respective tasks of the ICRC and the league. In terms of its claim to leadership within the movement, the ICRC prevailed against corresponding efforts by the league. A year later, with the Red Crescent and the Red Lion with the Red Sun, two further protective symbols, which have equal rights with the Red Cross, were included in the Geneva Conventions. While Iran was the only country that (until 1980) used the red lion with the red sun, the red crescent became the symbol of almost all national societies in Islamic countries.

During the war between Ethiopia and Italy (1935/1936), the league provided aid amounting to around 1.7 million Swiss francs, which came exclusively to the Ethiopian side due to Italy's refusal to cooperate with the International Red Cross. Mainly through attacks by the Italian army, 29 people who were working under the protection of the Red Cross lost their lives in this conflict. During the Spanish Civil War from 1936 to 1939, the league was again active together with the ICRC and was supported by 41 national societies. In 1937 and 1939 the league was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the then ICRC President Max Huber in his function as a member of the Institut de Droit international (Institute for International Law). In 1939, due to the beginning of the Second World War, the league relocated its headquarters from Paris to Geneva in order to be able to claim the protection resulting from Swiss neutrality for its activities.

The time after the Second World War

Shortly after the end of the Second World War, some governments as well as individual Red Cross societies called for the dissolution of the ICRC and the transfer of its powers to the League of Red Cross Societies. Alternatively, the then President of the Swedish Red Cross, Folke Bernadotte, suggested that the tasks of the committee and the league should be merged so that each national society should have a member of the international committee. The ICRC responded to these suggestions on the one hand through increased aid activities. On the other hand, at two conferences in 1946, it involved the national societies and in 1947 the governments of the international community in a revision of the Geneva Conventions, thereby emphasizing its special position in the field of international humanitarian law.

The adoption of the new versions of the Geneva Conventions in 1949 thus strengthened the position of the committee vis-à-vis the league and national societies. Three years later, the movement's statutes, adopted in 1928, were revised for the first time. From 1960 to 1970, the league saw a sharp increase in the number of recognized national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, of which there were more than 100 by the end of the decade. This trend was due in part to independence from previous colonies in Africa and Asia. On December 10, 1963, the League, together with the ICRC, received the Nobel Peace Prize.

On October 11, 1983, the league was renamed the League of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies . In 1986, the seven principles of the movement adopted in 1965 found their way into the statutes, which were revised again in the same year. In addition, as part of the revision of the statutes, the name International Red Cross was given up in favor of the new official name International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement . On 27 November 1991, the League was given the currently valid name International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (Engl. International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies , IFRC).

On October 19, 1994, during the 38th plenary session of the United Nations General Assembly, the Federation was also invited as an observer to the sessions of the UN and the meetings of its committees (resolution A / RES / 49/2). The 1997 Seville Agreement between the Federation and the ICRC defines the responsibilities of both organizations in international operations. The ICRC transferred some responsibilities to the federation, for example the care of refugees in countries without armed conflict.

In 1996 the ICRC was awarded the Balzan Prize for Humanity, Peace and Fraternity among the Nations.

The most extensive relief operation to date under the leadership of the Federation is the operation after the tsunami disaster in the Indian Ocean on December 26, 2004 with the participation of around 22,000 helpers from more than 40 national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies .

President of the Federation

The president of the federation has been the Italian Francesco Rocca since November 2017 . Vice-presidents are Brigitta Gadient by virtue of her office as representative of the Swiss Red Cross and as representative of the various world regions Kerem Kinik ( Turkey ), Miguel Villarroel ( Venezuela ), Abdoul Azize Diallo ( Senegal ) and Chen Zhu ( People's Republic of China ). Previous presidents, who were referred to as "Chairman" until 1977, were:

- 1919–1922: Henry P. Davison ( United States )

- 1922–1935: John Barton Payne ( United States )

- 1935–1938: Cary Travers Grayson ( United States )

- 1938–1944: Norman Davis ( United States )

- 1944–1945: Johannes von Muralt ( Switzerland )

- 1945–1950: Basil O'Connor ( United States )

- 1950–1959: Emil Sandström ( Sweden )

- 1959–1965: John A. MacAulay ( Canada )

- 1965–1977: José Barroso Chávez ( Mexico )

- 1977–1981: Joseph Adetunji Adefarasin ( Nigeria )

- 1981–1987: Enrique de la Mata ( Spain )

- 1987–1997: Mario Villarroel Lander ( Venezuela )

- 1997-2001: Astrid N. Heiberg ( Norway )

- 2001–2009: Juan Manuel Suárez Del Toro Rivero ( Spain )

- 2009–2017: Tadateru Konoé ( Japan )

activities

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement

Structure and organization

Members of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement are the International Committee of the Red Cross, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, and the national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. These organizations are linked within the movement through the International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, the Movement's Council of Delegates and the Standing Commission of the Red Cross and Red Crescent as common organs.

The international conference is the supreme organ of the movement. This is where the representatives of the national societies, the ICRC and the Federation, as well as the representatives of the states party to the Geneva Conventions, meet approximately every four years. It “contributes to the unity of the movement and to the further development of international humanitarian law and other international agreements of particular interest to the movement” and adopts its decisions, recommendations and declarations in the form of resolutions. The participants of the conference also elect the members of the standing commission and can delegate mandates to the ICRC or the federation within the framework of the statutes. Participants must respect the principles of the movement and refrain from speaking in any controversial political, racist, religious or ideological position.

The representatives of the National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, the ICRC and the Federation form the Council of Delegates. Within the framework of the statutes “the council expresses itself on every question concerning the movement and, if necessary, takes appropriate decisions” in a consensus procedure. The Council usually meets before an international conference. Representatives of new national societies in the recognition process have the opportunity to attend the meetings.

Between the international conferences, the Standing Commission is the administrator of the conference. It works to ensure that the Movement's organizations work together in harmony, seeks to implement the resolutions of the Conference and deals with matters that affect the Movement as a whole. It has nine members, including five members of the national societies, two representatives of the ICRC and two representatives of the Federation. The commission is responsible for determining the conference venue, the date, the program and the provisional agenda. In addition, it has the task of resolving disagreements that arise from the interpretation or application of the movement's statutes.

Summarized under the name “International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement”, the ICRC, the federation and the national societies currently have around 97 million active members around the world, around 300,000 of them full-time.

Principles

The on October 8, 1965 on the XX. International Conference from October 2 to 9, 1965, seven principles of the movement were promulgated by the XXV. International conference from 23 to 31 October 1986 adapted and read:

- Humanity (Engl. Humanity )

- Impartiality (Engl. Impartiality )

- Neutrality (Engl. Neutrality )

- Independence (Engl. Independence )

- Voluntary (Engl. Voluntary Service )

- Unit (engl. Unity )

- Universality (Engl. Universality ).

All members and organizations of the Red Cross or Red Crescent are committed to these principles.

Motto, Memorial Day and Landmarks

The first motto of the International Committee of the Red Cross was “ Inter Arma Caritas ” (German: “In the midst of weapons, humanity”). It was first used in 1888 by Gustave Moynier to mark the 25th anniversary of the Red Cross movement. He described a picture that showed a Red Cross helper in the midst of the war and was depicted in the ICRC's anniversary publication. The motto was spread on the respective issues of Bulletin International from 1889 onwards . It was supplemented in 1961 for the entire Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement with the slogan “ Per Humanitatem ad Pacem ” (German: “Through humanity to peace”). In these slogans, the historically determined orientation of both organizations to their priority tasks is expressed.

The Mission Statement of the "Strategy 2010" adopted by the Federation, based on the experience of the nineties, reads:

"To improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity"

"Improving the lives of people in need and the socially disadvantaged through the power of humanity."

From 1999 to 2004 all activities of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement were therefore under the slogan “ The power of Humanity ”. During the 28th International Conference in Geneva in December 2003, the conference motto “ Protecting human Dignity ” was chosen as the new slogan for the activities of the movement.

At the 16th International Red Cross Conference in London in 1938 it was decided to celebrate Henry Dunant's birthday on May 8th as a commemorative and public holiday of the International Movement. Since 1984 this day has been called " World Red Cross and Red Crescent Day ".

In Solferino, next to a small museum mainly dedicated to the Battle of Solferino and the history of the Italian Wars of Liberation, there is the Ossario di Solferino bone chapel, in which the skulls of 1,413 people killed in the battle and bones of around 7,000 other victims are kept. as well as the Red Cross memorial, inaugurated in 1959. In the same year, the International Museum of the Red Cross was opened in neighboring Castiglione delle Stiviere. The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum can be found right next to the headquarters of the ICRC in Geneva. The Henry Dunant Museum in Heiden on Lake Constance, which deals with the life and work of Henry Dunant, was set up in the hospital where he spent the last 18 years of his life.

Activities and organization of the ICRC

Mission and tasks

The mission of the ICRC as an impartial, neutral and independent organization is to protect the life and dignity of victims of war and internal conflict, and to support them. It directs and coordinates the international relief activities of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement in armed conflicts and thus after the agreement of Seville , the responsible body (Engl. Lead Agency ) of the Movement for appropriate situations. The original tasks of the ICRC as defined by the Geneva Conventions and the Statute of the Committee include the organization and implementation of the following measures in war and crisis situations:

- Monitoring compliance with international humanitarian law, in particular the Geneva Conventions

- Care and care for the wounded

- Monitoring the treatment of prisoners of war and their care

- Family reunification and the search for missing persons (tracing service)

- Protection and care for the civilian population

- Mediation between the conflicting parties

In 2006 ICRC delegates visited around 478,000 prisoners at around 2,600 locations in 71 countries, of which almost 25,400 prisoners were visited and registered for the first time. About 300,000 Red Cross messages were exchanged between separated family members. The whereabouts of around 11,600 people could be determined for the first time, and almost 1,100 children were reunited with their families. Around 2.6 million people received help from the ICRC in the form of food, around four million in the form of tents, blankets, hygiene articles and similar materials, 15.9 million in the form of water and sanitary facilities and around 2.4 million in form from health stations and similar facilities. Around 18,000 members of military, security and police units in more than 100 countries received instruction on international humanitarian law through the ICRC in more than 300 courses.

Structure and organization

The ICRC has its headquarters in Geneva and branches in around 80 other countries. In 2006, around 12,500 people were deployed around the world for the international activities of the committee, around 800 of them at the headquarters in Geneva, around 1,500 so-called expatriates , half of whom were delegates to lead international missions, as well as specialists such as doctors, engineers, logisticians, translators and others , and around 10,200 members of national local societies. Contrary to popular belief, the ICRC is neither a non-governmental organization nor, as the name suggests, an international organization in terms of its structure and organizational form. The word “international” in the name refers to the mandate given by the worldwide community of states in the Geneva Agreement and comes from the term “inter nationes” (between the states). The Geneva Conventions are thus the basis of international law and, together with the statutes of the committee, the legal basis for its activities. In addition, through contracts with individual states and international organizations as well as through national laws in individual countries, it has further rights, privileges and immunity protection to carry out its tasks. With regard to the legal basis for its existence and organization, the ICRC is a private association under Swiss association law. According to its statutes, it consists of 15 to 25 Swiss citizens who are co-opted by the committee itself for a period of four years each . A multiple re-election is possible, after three terms a three-quarters majority of all committee members is necessary for each future re-election.

The two main bodies of the ICRC Directorate (engl. Directorate ) and the assembly (engl. Assembly ). The directorate is the executive body of the committee and consists of a director general and five directors responsible for operations, personnel, resources and operational support, communications, and international law and cooperation within the movement. The members of the directorate are appointed by the assembly for a four-year term. The assembly, made up of all members of the committee, meets regularly and is responsible for setting goals, guidelines and strategies, monitoring the activities of the committee and controlling the budget. Its president is the president of the committee, who is elected for a four-year term. He has two vice-presidents at his side. While one of the two vice-presidents also serves for four years, the term of the second is not limited, but ends with the resignation from office or the departure from the committee. The assembly also elects an Assembly Council consisting of five members . The assembly delegates decision-making powers in certain matters to him. In addition, the Assembly Council prepares the meetings of the Assembly and acts as a liaison between the Assembly and the Directorate.

Due to Geneva's location in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, the ICRC usually operates under its French name Comité international de la Croix-Rouge or the resulting abbreviation CICR. The ICRC uses the red cross on a white background with the inscription “COMITE INTERNATIONAL GENEVE” in a circle as a symbol.

financing

The ICRC's budget is largely raised by Switzerland as the depositary state of the Geneva Conventions and their signatory states as well as the national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, and to a lesser extent by international organizations such as the European Union and through donations from companies, associations and private individuals . All these payments are made voluntarily on the basis of donation appeals separately for the areas of internal operating costs and relief operations ( Headquarters Appeal and Emergency Appeals ). These calls are handed out annually by the ICRC to representatives of possible supporters. The financial planning of the ICRC is seen in diplomatic circles as an early warning system for humanitarian crises due to its thoroughness.

The planned total budget for 2011 is around 1.23 billion Swiss francs, the highest level in the history of the committee. It is divided into 1.05 billion Swiss francs (85.1 percent) for aid missions and 183.5 million Swiss francs (14.9 percent) for internal costs. The increase compared to the previous year is approx. 11.6 percent in the planned expenditure for aid missions and 6.1 percent in the expected internal costs. With a forecast total requirement of 385.5 million Swiss francs, around 37 percent of the planned expenditure for relief missions, the focus of operations is, as in previous years, in Africa . The ICRC's mission in Afghanistan is its most extensive mission, with an estimated cost of CHF 89.4 million, followed by operations in Iraq (CHF 85.8 million) and Sudan (CHF 82.8 million).

Federation activities and organization

Mission and tasks

The federation coordinates the cooperation between the national societies within the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and supports the founding and development of new national societies in countries in which no corresponding society exists. At the international level, the Federation organizes and leads in particular relief operations in non-armed emergency situations, such as after natural disasters, technical accidents, epidemics, mass exodus and after the end of an armed conflict. According to the Seville Agreement , the federation is the responsible body of the movement (English Lead Agency ) for such operations. It works with the national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies of the countries concerned (English Operating National Societies , ONS) as well as national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies of other countries (English Participating National Societies , PNS). Of the current 192 national societies, either as members or as observers (Engl. Observer ) of the General Assembly of the Federation members are between 25 and 30 regularly as PNS in other countries. The most active national societies at international level include the American Red Cross , the British Red Cross , the German Red Cross and the national Red Cross societies of Sweden and Norway. The Federation also supports the ICRC in its missions. A current focus of the work of the federation is the commitment to a ban on landmines and the medical, psychological and social care of mine victims.

The tasks of the federation can therefore be summarized in the following areas:

- Spreading humanitarian principles and values

- Responding to disasters and other emergencies through relief efforts

- Disaster preparedness through training and further education of aid workers as well as the provision and distribution of relief supplies

- Health care and social medical care at the local level

Structure and organization

The federation is also headquartered in Geneva and has 14 regional offices in different regions and around 350 delegates in more than 60 countries. The binding legal basis of the federation with regard to its goals, its structure, its financing and its cooperation with other organizations including the ICRC is its constitution. The executive body of the Federation is the Secretariat under the direction of the Secretary General . The Secretariat are four departments (Engl. Divisions ) for "supporting services" (English. Support Services ), "support the national societies and the work on the ground" (Engl. National Society and Field Support ), "Strategy and contacts" ( English Policy and Relations ) and "Cooperation within the Movement" (English Movement Cooperation ). The latter department is responsible for working with the ICRC.

The highest organ of the Federation is the General Assembly , which meets every two years and consists of delegates from all national societies. It also appoints the Secretary General. Between the meetings of the General Assembly, the Governing Board is the governing body and as such also has decision-making powers in certain matters. The Board of Directors consists of the President and Vice-Presidents of the Federation, the Chairman of the Finance Commission and elected representatives of national companies. It reports to four other commissions for “Health and Community Services”, “Youth Work”, “Disaster Relief” and “Development”.

For its activities, the federation uses the combination of a red cross (left) and a red “crescent” (right) on a white background (usually surrounded by a red border) and without any further lettering as a mark.

financing

The federation finances the regular costs of its activities through contributions from the national societies of which it is a member, as well as through income from investments and financial transactions. The amount of the contribution payments is determined by the finance commission and confirmed by the general assembly. Additional income, especially for unforeseen special expenses, comes primarily from voluntary payments by national companies, governments, other organizations, private companies and individuals. For this purpose, the federation publishes appeals for donations depending on specific needs, especially for aid missions that arise at short notice.

In 2009 the federation generated income of 36.0 million Swiss francs from contribution payments, 4.6 million Swiss francs from non-earmarked donations, 14.2 million Swiss francs from investments and financial transactions, and around 17.6 million Swiss francs from others Payments. In addition, there were earmarked donations based on appeals totaling 282.6 million Swiss francs and 33.0 million Swiss francs in the form of other earmarked services. In contrast, there were expenditures totaling 475.6 million Swiss francs. The resulting shortfall was financed entirely from reserves, which in 2009 were CHF 442.6 million, including CHF 249.4 million in cash.

Activities and organization of the national societies

Mission and tasks

The original tasks of a national society arising from the Geneva Conventions and the statutes of the movement include providing humanitarian aid in the event of armed conflicts and other major emergency situations such as natural disasters, as well as disseminating knowledge of international humanitarian law. Both the ICRC and the Federation cooperate with the national societies in their respective activities, particularly with regard to the personnel, material and financial resources of aid missions.

Most of the national societies also carry out other humanitarian tasks in their home countries, within the framework of their respective personnel, financial and organizational possibilities. In their home country, for example, many societies play an important role in the blood donation system , in civil rescue services or in social services such as care for the elderly and the sick . In these countries, the national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies thus also act as service providers in the health sector and as charities .

Structure and organization

National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies exist in almost every country in the world. In principle, in their home country they exercise the tasks, rights and obligations of a national society resulting from the Geneva Conventions. The recognition of an aid organization as a national society within the meaning of the conventions is carried out by the ICRC on the basis of the movement's statutes and by the government of the home country. Article 4 of these statutes contains ten requirements for recognition by the ICRC:

- The organization operates on the territory of an independent state that must have signed the Geneva Conventions.

- The organization is managed by a central body that acts as the sole decision-making body of the organization and the point of contact for the movement, and is the only national Red Cross or Red Crescent Society in its home country.

- The respective government has recognized the organization as a voluntary aid society within the meaning of the Geneva Conventions.

- The organization is legally independent and able to act in full compliance with the principles of the movement at all times.

- The organization uses a name and symbol in accordance with the Geneva Conventions and their additional protocols.

- The organization is organized in such a way that it can at any time fulfill the tasks set out in its own statutes, including the obligation under the Geneva Conventions to prepare in peacetime for humanitarian aid in the event of an armed conflict.

- The organization is active on the entire national territory of its home country.

- Their voluntary members are accepted without any consideration of race, gender, class, religion or political views.

- The organization follows the movement's statutes and is ready to cooperate with all members of the movement.

- The organization respects the fundamental principles of the movement and works according to the principles of international law.

After recognition by the ICRC, you are accepted into the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. As of November 2016, 190 national societies are recognized as full members of the movement. The national society of Eritrea currently has observer status in the General Assembly of the Federation. The Tuvalu Red Cross Societies were the last national societies to join the federation.

Despite its formal independence, every national society is bound by the legal situation in its home country with regard to its organization and activities. In many countries the national societies enjoy special status on certain points based on agreements with their governments or corresponding laws in order to guarantee the full independence required by the movement. However, in the course of history there have repeatedly been examples of national societies that have been institutionalized by the state and, in particular, instrumentalized for military purposes. Such involvement in state structures and activities is, however, in contradiction to the principles of independence and neutrality.

financing

The national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies finance their activities primarily through state grants from the governments and authorities of their respective home countries, through donations from private individuals, companies and other institutions, and through income from economic activities, in particular the provision of services in the health and social sectors . Depending on the legal situation, they are usually recognized as a non-profit organization.

Symbols

Differentiation between protective symbols and symbols

The symbols described below have a dual function. On the one hand, they serve in certain situations as a symbol of protection within the meaning of the Geneva Conventions (Red Cross, Red Crescent, Red Lion with Red Sun, Red Crystal), and on the other hand, as a mark of organizations that belong to the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

As a protective symbol, they are used to mark people and objects (buildings, vehicles, etc.) who are deployed in the event of an armed conflict to implement the protective regulations and aid measures agreed in the Geneva Agreement. This use is called "protective use ". These symbols may also be used as protective symbols by corresponding organizations and institutions that are not part of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, such as the military medical services or civil hospitals. When used as a protective measure, they are visible as far as possible, for example by means of flags, and must be used without additives.

When used as a badge, these symbols indicate that the person or entity concerned is part of a particular Red Cross or Red Crescent organization such as the ICRC, federation or national society. Such use is referred to as " indicative use ". In this case, the symbols should be smaller and with a corresponding addition such as "German Red Cross".

The improper use of the Red Cross symbol is prohibited by national regulations in many countries, for example in Germany by Section 125 of the Law on Administrative Offenses and the DRK Act , in Switzerland by the Federal Law on the Protection of the Mark and the Name of the Red Cross ( SR 232.22 ) or in Austria by the Red Cross Act .

Red cross on a white background

The red cross on a white background was designated as the original protection and identification symbol. It is the color reversal of the Swiss flag , a definition that was adopted in honor of the Red Cross founder Henry Dunant and his home country. The idea for a uniform trademark and for its design goes back to the founding members of the International Committee Louis Appia and General Guillaume-Henri Dufour . For the white base color, Dufour resorted to military tradition, according to which the wearing or hoisting of a white flag indicated that the porters were not part of the fighting force . It is sometimes assumed that Henry Dunant himself could observe the use of members of the Nursing Order of the Camillians at the Battle of Solferino or elsewhere in Italy and that their conspicuous order emblem (a sewn red fabric cross on the black priest's robe ) could be the choice of the protective symbol of the international Red Cross - have influenced movement. The founder of the order, Kamillus von Lellis , deliberately chose this emblem in the 16th century in order to be recognized by a striking symbol as a helper for those suffering from the plague.

As a protective symbol, the Red Cross is described in Article 7 of the Geneva Convention of 1864 and Article 38 of the 1st Geneva Convention (of August 12, 1949) “for the improvement of the lot of the wounded and sick in the armed forces in the field”. When designing the cross as a mark, a cross composed of five squares is usually used for practical reasons. However, this is only an internal Red Cross agreement, officially - for use as a protective symbol - every red cross on a white background is to be recognized, regardless of formal requirements. Of the 190 recognized national societies, 152 currently use the red cross as a mark, in addition to the national society of Tuvalu , which has applied for their recognition.

Red crescent

In the Russo-Ottoman War (1876–1878), the Ottoman Empire used the Red Crescent instead of the Red Cross because the Ottoman government was of the opinion that the Red Cross would offend the religious sentiments of its soldiers. In 1877, at the request of the ICRC, Russia undertook to recognize the inviolability of all persons and institutions marked with the Red Crescent, whereupon the Ottoman government announced the full recognition of the Red Cross in the same year. After this de facto equality of the Red Crescent with the Red Cross, the International Committee declared in 1878 that in principle there was the possibility of including a further protective symbol in the provisions of the Geneva Convention for non-Christian states, since principles of humanity must take precedence religious beliefs. The Red Crescent was formally recognized in 1929 by a diplomatic conference of the signatory states to the Geneva Conventions (Article 19 of the First Geneva Convention in the version of 1929) and was used as such by Egypt and the newly founded Republic of Turkey. Since the official recognition, the national societies of almost all Islamic countries have been using the red crescent as a symbol of protection and protection since their respective founding. The national societies of some countries, such as Pakistan (1974), Malaysia (1975) and Bangladesh (1989), changed their names and symbols from the Red Cross to the Red Crescent. The Red Crescent is currently used as a designation by 33 of the 186 recognized national societies.

Red lion with red sun

Iran and its corresponding aid society , the Iranian Society of the Red Lion with the Red Sun , used a red lion with a red sun based on the old flag and coat of arms of Iran from 1924 to 1980. Formal recognition as a protective symbol took place in 1929 together with the red crescent through the revision of the Geneva Conventions. Despite the change to the red crescent in 1980, Iran continues to expressly reserve the right to use the red lion with the red sun , which therefore continues to have the status of an officially recognized trademark.

Red crystal: the sign of the Third Additional Protocol

As early as 2000, after a discussion that had been going on for several years, an attempt was made for the first time to introduce a further symbol next to the Red Cross and the Red Crescent. The background to this was the debate about the recognition of the Israeli society Magen David Adom (MDA) with its Red Star of David, which numerous Islamic states had blocked for decades. Further attempts to introduce new protective symbols or separate regulations were, for example, applications by the national societies of Thailand (1899 and 1906) for a combination of a red cross and a red flame (based on Buddhist symbolism), Afghanistan (1935) after recognition of a red archway ( Mehrab-e-Ahmar) based on his national flag at the time, as well as Sri Lankas (1957) and India (1977) after using a red swastika . The national societies of Kazakhstan (currently the Red Crescent) and Eritrea (currently the Red Cross) are also striving to use a combination of the Red Cross and the Red Crescent, similar to the combination of the two symbols used by the Alliance of Red Cross and Red Crescent Soviet Union societies until their dissolution was used. The national society of Eritrea currently only has observer status in the General Assembly of the Federation.

A diplomatic conference with the participation of all 192 signatory states is necessary for changes and additions to the protective symbols and thus to the Geneva Conventions. However, the conference planned for 2000 was canceled due to the start of the Second Intifada in the Palestinian territories. Five years later, the Swiss government again invited to such a conference. This was originally supposed to take place on December 5th and 6th, 2005, but was then extended to December 7th. After Magen David Adom had signed an agreement with the Palestinian Red Crescent in the run-up to the conference that regulated responsibilities and cooperation in operations in the Palestinian territories, Syria demanded a similar agreement for its Red Crescent Society's access to the Golan Heights . Corresponding negotiations with MDA, however, did not lead to an amicable result despite compromise offers made by the ICRC to Syria. As a result, the third additional protocol to the Geneva Conventions, which regulates the introduction of the new trademark, was not adopted by consensus, as has been the case up to now. In a vote, 98 of the states present approved the protocol, 27 rejected it and ten abstained. Since the necessary two-thirds majority was thus achieved, the minutes have been adopted.

The newly introduced symbol is a red square standing on a point, into which one of the other emblems or a combination of these can also be inserted when used as a mark of a national society. The official name is "Sign of the Third Additional Protocol". For the colloquial usage is from the ICRC and the Federation, in contrast to previous proposals like "Red Diamond" (English. Red Lozenge ) or "Red Diamond" (English. Red Diamond ) the term "Red Crystal" favored since the abbreviation "RC “For whose English translation Red Crystal is identical to the abbreviations for Red Cross (Red Cross) and Red Crescent (Red Crescent). The same applies to the abbreviation “CR” of the French terms Croix Rouge (Red Cross), Croissant Rouge (Red Crescent) and Cristal Rouge (Red Crystal).

During the 29th International Red Cross and Red Crescent Conference in Geneva on June 21, 2006, of the 178 delegations from national societies present and 148 delegations from contracting parties to the Geneva Conventions, a total of 237 approved an amendment to the statutes of the Movement for the Acceptance of the Red Crystal. 54 delegations voted against, 18 abstained. The two-thirds majority required for the change was thus clearly achieved. On the basis of this decision, the ICRC decided to recognize Magen David Adom and the Palestinian Red Crescent as national societies. As a result, both societies were accepted as full members of the federation.

Red Star of David

The National Society of Israel, Magen David Adom (MDA), has used the Red Star of David as an emblem since its inception in 1930 . After the establishment of the MDA, efforts on the part of the organization to equate the symbol with the recognized trademarks of the Geneva Conventions were rejected by the ICRC due to fears that the spread of new symbols would be impractical. A request by Israel to include the Red Star of David as an additional symbol of protection in the Geneva Conventions was rejected when the agreement was revised in 1949 with 21 votes against, 10 votes in favor and 8 abstentions. Consistently, Israel signed the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 while recognizing the previous protective symbols only with the proviso that it itself used the red Star of David as a protective symbol .

Since the statutes of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement contain the use of a recognized trademark as a condition for the recognition of a national society, Magen David Adom was denied full membership in the movement until the third additional protocol was passed. The organization has agreed to use the red crystal on missions abroad, with or without a Star of David inside the crystal, depending on the situation. The rules of the Third Additional Protocol allow Magen David Adom to continue using the Red Star of David within Israel's borders.

Despite the restrictions that existed in the past, Magen David Adom has enjoyed a high reputation within the movement for many years and is involved in a wide range of international activities through cooperation with the ICRC and the International Federation.

Unrecognized symbols of national societies

In addition to the symbols already mentioned, a large number of symbols for National Societies have been proposed in the course of the Red Cross history:

- Afghanistan: Aid Society Mahrab-e-Ahmar (Red Archway)

- Cyprus: Red Cross and Red Crescent Society

- India: red wagon wheel; analogous to the wheel in the national flag of India

- Japan: Aid society Hakuaisha , red dot and line one above the other

- Lebanon: red cedar; analogous to today's Lebanon cedar in the national flag of Lebanon

- Sudan: red rhinoceros

- Sri Lanka: Society of Shramadana : Red Swastika (proposed 1957); red lion carrying a sword (proposed in 1965)

- Syria: red palm leaf

- Thailand: Sabha Unalome Deng ; Applied for Society of the Red Flame (1899 and 1906)

- Soviet Union: Alliance of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

- Zaire: Society of the red lamb of central Congo .

All of the companies listed later submitted to the terms of recognition of the Red Cross and selected one of the trademarks recognized under international law as their mark.

Uniform symbol for the entire movement

In April 2016, the ICRC announced that a uniform logo had been developed for the entire Red Cross movement. These are the two protective symbols, the Red Cross and the Red Crescent, surrounded by a three-quarter circle with the inscription "INTERNATIONAL MOVEMENT". Additional labels in the movement's languages (Arabic, Chinese, French, Russian and Spanish) have also been adopted. This uniform logo should be used for joint calls or similar by the ICRC, federation and national societies, for example for calls for donations for humanitarian crises, campaigns or global interest.

literature

German-language books

- Jean-Claude Favez: The International Red Cross and the Third Reich: Could the Holocaust be Stopped? Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-85823-196-7 (and Bertelsmann, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-570-09324-7 ).

- Jean Pictet: The Principles of the Red Cross. A comment. Henry Dunant Institute, Geneva / Bonn 1990.

- Hans Haug, Hans-Peter Gasser, Francoise Perret, Jean-Pierre Robert-Tissot: Humanity for everyone. The world movement of the Red Cross and the Red Crescent. 3. Edition. Haupt Verlag, Bern 1995, ISBN 3-258-05038-4 .

- Henry Dunant: A Memory of Solferino. Self-published by the Austrian Red Cross, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-9500801-0-4 .

- Roger Mayou (Ed.): Cornelia Kerkhoff (German translation): Internationales Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum. Self-published by the museum, Geneva 2000, ISBN 2-88336-009-X .

- Hans Magnus Enzensberger : Warriors without weapons. The International Committee of the Red Cross. Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2001, Die Other Bibliothek series , ISBN 3-8218-4500-7 .

- Dieter Riesenberger : For humanity in war and peace. The International Red Cross 1863–1977. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-01348-5 .

- Gerald Steinacher: Swastika and Red Cross. A humanitarian organization between the Holocaust and the refugee problem. StudienVerlag, Innsbruck [u. a.] 2013, ISBN 978-3-7065-4762-8 .

- Robert Dempfer: The Red Cross: About heroes in the spotlight and discreet helpers. Deuticke, Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-552-06092-0 .

- Daniel-Erasmus Khan: The Red Cross: History of a World Humanitarian Movement. Verlag Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-64712-3 .

- Thomas Brückner: Give help. Relations between the ICRC and Switzerland 1919–1939. Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 2017, ISBN 978-3-03810-194-9 .

English language books

- David P. Forsythe: Humanitarian Politics: The International Committee of the Red Cross. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1978, ISBN 0-8018-1983-0 .

- Georges Willemin, Roger Heacock: International Organization and the Evolution of World Society. Volume 2: The International Committee of the Red Cross. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Boston 1984, ISBN 90-247-3064-3 .

- Pierre Boissier : History of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Volume I: From Solferino to Tsushima. Henry Dunant Institute, Geneva 1985, ISBN 2-88044-012-2 .

- André Durand : History of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Volume II: From Sarajevo to Hiroshima. Henry Dunant Institute, Geneva 1984, ISBN 2-88044-009-2 .

- International Committee of the Red Cross: Handbook of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. 13th edition. ICRC, Geneva 1994, ISBN 2-88145-074-1 .

- John F. Hutchinson: Champions of Charity: War and the Rise of the Red Cross. Westview Press, Boulder 1997, ISBN 0-8133-3367-9 .

- Caroline Moorehead : Dunant's dream: War, Switzerland and the history of the Red Cross. HarperCollins, London 1998, ISBN 0-00-255141-1 (hardcover); HarperCollins, London 1999, ISBN 0-00-638883-3 (paperback edition).

- François Bugnion: The International Committee of the Red Cross and the protection of war victims. ICRC & Macmillan (Ref. 0503), Geneva 2003, ISBN 0-333-74771-2 .

- Angela Bennett: The Geneva Convention: The Hidden Origins of the Red Cross. Sutton Publishing, Gloucestershire 2005, ISBN 0-7509-4147-2 .