Biological weapon

Biological weapons are weapons of mass destruction , where pathogens or natural toxins ( toxins ) specifically as a weapon can be used. Biotic toxins, although not biological agents in the strict sense, are classified as biological weapons and not chemical weapons because of their origin from living organisms and are therefore not regulated by the Chemical Weapons Convention . About 200 possible pathogens are currently known that can be used as biological weapons so far. Since 1972 are through the Bioweapons Conventionthe development, manufacture and use of biological weapons are prohibited. There is also the theoretical approach for a biogenic or ethnic weapon , which is only directed against one ethnic group.

Biological warfare agents

Biological warfare agents can be directed against organisms (e.g. humans, animals or plants) as well as against materials. For example, the USA is researching bacteria, which decompose fuel, and fungi, which can break down the camouflage color of aircraft. Biological warfare agents differ from chemical weapons in that chemical weapons are ready for use, i.e. they can be used at any point in time and in any location. Biological warfare agents, on the other hand, must first be processed and appropriately disseminated. The research of Robert Koch , who was the first to discover the anthrax pathogen and a method for breeding bacteria, paved the way for the manufacture of larger quantities of biological weapons - although this was not intended by Koch.

- Some pathogenic bacteria are among the best-known B-warfare agents. Examples are the anthrax causing Bacillus anthracis , as well as Yersinia pestis (pathogen of the plague ), Vibrio cholerae (pathogen of cholera ), Coxiella burnetii (pathogen of Q fever ) or Francisella tularensis (pathogen of tularemia ). The B-warfare agents are more effective, the less effective antibiotics are available to the enemy.

Some bacteria, such as the anthrax bacillus, form very resistant forms of persistence ( endospores ) outside the host . Rickettsiae are intracellular parasites and also belong to the bacteria. However, due to their restricted metabolism, they are highly dependent on the host and can only be cultivated in organic tissue in the laboratory. They are mainly transmitted to humans by fleas , ticks , animal lice and mites . A typical disease caused by rickettsiae is typhus .

- Viruses are intracellular parasites without a metabolism of their own. The diagnosis of a virus is more time-consuming than with bacteria, since viral infections in the early stages are often accompanied by flu-like symptoms and therefore specific viruses are difficult to detect. The most effective fight against viruses is carried out with the help of immunizations through vaccination . A viral disease that has broken out can only be combated with antivirals . These make it more difficult for the virus to multiply in the body, but are not able to fight the viruses themselves. For biological weapons, viruses are particularly relevant, which trigger acute symptoms of illness and against which prophylactic vaccination protection is not sufficiently available in the population. Examples of such diseases are smallpox and diseases associated with hemorrhagic fever such as Ebola , Lassa fever or yellow fever . In addition, viruses can also cause animal diseases such as foot-and-mouth disease , cattle or swine fever .

- Fungi are not considered to be actual biological warfare agents, since they cannot normally cause acute diseases in humans. However, they play an important role as plant pathogens and can thus be used to damage agriculture. Many fungal diseases in plants are able to spread relatively quickly. For example, mushrooms, which specifically infect the coca bush , opium poppy and cannabis sativa , are being developed for the fight against drugs . The US developed Agent Green (a type of Fusarium ) for this purpose.

- Toxins are produced by many organisms (e.g. botulinum toxin by bacteria or ricin by plants). Many hundreds of toxins are known today. Toxins often serve their producers in the fight against other organisms (e.g. predators, hosts or competing microorganisms); they are thus quasi natural biological "warfare agents" of the organisms that produce them.

Categories

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put together a subdivision that divides the warfare agents into three categories depending on availability, lethality rate , risk of infection and treatment option.

- Category A: This includes diseases that pose a problem for the security of states, can be spread or transmitted easily and have a high mortality rate. These diseases include smallpox, plague and anthrax as well as poisoning with botulinum toxin , ricin & abrin , aflatoxin and hemorrhagic fever.

- Category B: Pathogens in this category are relatively easy to spread, have a medium lethality rate and can be easily contained or monitored. Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), Brucellen or Burkholderia mallei ( snot ) belong to this group.

- Category C: This includes either warfare agents that are very readily available or can be easily acquired, but have a low lethality rate, or pathogens that have a high lethality rate but are either difficult to transmit or are hardly available. But also pathogens that are dangerous but can be treated easily. This category includes, for example, the yellow fever virus or multi-resistant mycobacteria ( tuberculosis ).

Transmission / routes of infection

In extreme cases, the transmission of bacteria, viruses and toxins to the human body can occur through any contact with an infected material. However, there are also pathogens that cannot be transmitted from person to person, such as anthrax bacilli. Pathogens can be ingested in practically every imaginable form, and many warfare agents take a different course of disease depending on the route of absorption. Possible routes of infection are:

- Aerosols : The most effective and likely route of infection for a biological weapon attack is via aerosols. The substances can be applied using spray devices or explosive devices. When using explosive bodies, a large part of the pathogens is often rendered harmless by the great heat and pressure that is generated. Any cooling devices only create a slight increase in effectiveness, which is why explosive bodies are hardly suitable for large-scale use of bio-attacks. Spray devices are much more effective, but also less controllable. These can be attached to an aircraft, as they are already used today for pest control in agriculture , but they can also be effective in smaller versions, for example as a spray can .

Other, more secondary routes of infection would be, for example:

- Droplet infection : Diseases that are transmitted by droplet infection are usually extremely contagious. So they have the military advantage that they infect many people with a few pathogens, but the disadvantage that they are difficult to contain once they have infected enough people. Such diseases spread very quickly into pandemics , examples of which are plague, smallpox, Ebola and other hemorrhagic fevers, but also diseases such as flu or herpes simplex .

- Contact with body fluids: Body fluids that transmit diseases are primarily blood , semen , vaginal secretions , tears , nasal secretions and saliva . All diseases that can be transmitted from person to person can be transmitted through body fluids, whereby the type of body fluid transmitted can differ depending on the pathogen.

- Oral infection: Such pathogens are ingested, for example, through ingestion of infected meat or water. In this case, the diseases often originate in the intestine. In this way, pathogens that only affect animals can be transmitted to humans. BSE is a well-known example of this.

- Animals: Many animals act as hosts or intermediate hosts as carriers of disease. Well-known vector animals are rats , mites or animal lice for the plague . The anopheles mosquito is known to be the carrier of malaria .

- Medical utensils: This transmission, usually via uncleaned needles, is basically nothing more than the transmission of body fluids, but can take a different course, depending on where the wound is.

story

Antiquity and the Middle Ages

As early as 3,000 years ago, the Hittites were deliberately using contaminated cattle in enemy territory in order to severely restrict their diet. 2,000 years ago Persians, Greeks and Romans contaminated the wells of their enemies with rotting corpses. From Scythian archers around 400 BC. It is known that they coated their arrows with excrement, body parts and blood of the sick, but this was not as effective as coating the arrowheads with plant or animal poison. 184 BC Chr. Ordered Hannibal of Carthage in the service of King Prusias I of Bithynia his men in a battle with poisonous snakes filled jars on the ships of his enemies, the Pergamonen led by Eumenes II. To throw. During the Third Crusade (1189-1192), the English king took Richard the Lionheart Acre one , but the residents had barricaded themselves in it. To force the surrender, Richard had his soldiers collect several hundred beehives and throw them over the walls, whereupon the residents surrendered immediately. In 1346 the population of the city of Kaffa (today: Feodossija ) was shot at by the Tatars after three years of siege with their plague deaths by catapulting them over the walls . Today it is assumed that the following great wave of plague in Europe (" Black Death ") began with the infected refugees from the city. The same is said to have happened in 1710 by Russian soldiers during the siege of the then Swedish city of Reval (today: Tallinn).

18th century

Both the British and the French used biological weapons in combating the North American indigenous peoples. Since the diseases brought in from Europe had never occurred in this area, i.e. the indigenous peoples were not infected , the course of the disease was much more difficult than in Europeans. In May 1763, Pontiac Uprising Indians reached Fort Pitt , which was overcrowded with refugees from the area. Due to the poor hygienic conditions, smallpox broke out in the camp. The sick were quarantined on the instructions of the camp commandant Colonel Henri Louis Bouquet . On June 23, two emissaries from the rebellious Indians arrived at the fort and offered the British safe conduct if they abandoned the camp. The British refused, but gave the Indians two smallpox-contaminated blankets from the smallpox hospital, which they ignorantly accepted. After the blankets were handed over, smallpox actually broke out among the Indians. However, it is not clear whether this epidemic was due to the attack. Until 1765, reports of smallpox epidemics among the Indians appeared again and again. It is unclear whether the Commander of the British Armed Forces, Jeffrey Amherst was privy to this endeavor. In a letter to Bouquet dated July 7th, he asked: "Couldn't we try to send smallpox to these unfaithful Indians?" However, since the said blankets had already been given to the Indians on June 23, it is unlikely that this order came from him. As the letter progressed, Amherst wrote: "We must use every method to extinguish this hideous race".

Reports of smallpox attacks surfaced several times in America, for example during the American Revolutionary War , in which the Americans accused the British of inoculating their soldiers against smallpox in order to then infect the American troops while their own troops would be immune. The inoculation was carried out at that time due to the lack of vaccination . Pathogens were brought into open wounds, which caused the disease to break out, but it was much milder. In 1781, American soldiers found the bodies of African slaves who had died of smallpox. The Americans suspected that the British intended to cause an epidemic. In fact, it appears from a letter from Alexander Leslie that the British intended to smuggle the slaves on American farms.

First and Second World War

Until the 19th century, bio-attacks were only possible through the spread of diseases that were already rampant, but not through the artificial generation of the pathogens. That only changed when research began to grow bacteria. At the beginning of the First World War , Germany already had a large number of different B-weapons. The German army command initially considered using Pesterreger against the British, but the proposal was rejected in order to “prevent unnecessary suffering”, with Germany at the forefront of the warring states when it comes to chemical weapons .

During the First World War, only acts of sabotage were carried out that were directed against animals, since the cavalry was still of considerable importance at least at the beginning of the First World War and animals were often still used for the transport of material. Animals were often used for experimental purposes. However, there was never an open bio attack on the battlefield. In Germany these attacks were planned from 1915 onwards by a separate ministry, the “ Politics Section ”, which was headed by Rudolf Nadolny . The encrypted orders to the agents were mostly to poison horses, sheep or cattle as well as animal feed with pathogens that were produced in German laboratories and smuggled into the target country. Attacks took place in Romania, Spain, Argentina, the USA, Norway and Iraq; presumably in other countries as well. In Argentina, around 200 mules perished in anthrax attacks between 1917 and 1918 . However, it has not been proven whether the entire German army command was privy to these attacks.

In 1916 the Bucharest police confiscated several cultures of the pathogen causing snot disease from the German embassy .

In January 1917, a German saboteur, Baron Otto Karl von Rosen, and his companions were arrested by the Norwegian police because they could not identify themselves. The police found several kilograms of dynamite and several sugar cubes with anthrax germs embedded in their luggage. Although the baron testified that he and his group were from the Finnish independence movement and had planned actions against the Russian transport and communications system, his helpers confessed to having planned sabotage in Norway on behalf of Germany. The German orders regarding the anthrax spores were to infect reindeer carrying British weapons. After three weeks, the baron, who had German, Finnish and Swedish citizenship, was expelled from Sweden due to diplomatic pressure. Other well-known German secret agents were z. B. Anton Dilger and Frederick Hinsch.

At the end of 1917, the Germans largely stopped their bioweapons program.

The Entente powers were informed of the German B attacks from 1917 onwards. And since the German Reich was a leader in chemical and biological research on weapons, many other major states started their own bioweapons programs out of fear of the German bioweapons program. For example France in 1922, Soviet Union in 1926, Japan and Italy in 1932, Great Britain and Hungary in 1936, Canada in 1938 and the USA in 1941.

Empire of Japan

In 1932 in was Empire of Japan , the unit 731 established after the conquest of Manchuria and conducted from the beginning experiments on living people. The aim was to develop a biological weapon that could be used against the Chinese armed forces and the Red Army if the worst came to the worst. After the attack on China , research was massively intensified. Several other Japanese army units also researched biological weapons and carried out experiments on humans during World War II . Unit 731 alone killed around 3500 people, mostly during vivisection and full consciousness.

The first documented biological weapon attacks in China occurred in 1940 and were more experimental in nature. Mainly ceramic bombs full of plague- infected fleas were dropped over cities, such as on October 29, 1940 over Ningbo . At the end of 1941, Japanese troops released around 3,000 Chinese prisoners of war after they had previously been infected with typhus. This caused an epidemic among both Chinese troops and the population.

On May 5, 1942, a large-scale retaliation by Japanese troops began for the so-called Doolittle Raid , in which about 50 Japanese had been killed, which in turn was a retaliation for the attack on Pearl Harbor . Regular army units of the Japanese army withdrew from the areas designated for the action in the Chinese provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangxi , while troops from Unit 731 moved into these areas and began to contaminate all drinking water with anthrax. At the same time, the Japanese Air Force dropped the warfare agent over cities or sprayed it over residential areas. 250,000 people were murdered in the course of this action. In further acts of revenge, the Japanese army used cholera , typhus , plague and dysentery .

During the Battle of Changde , Japanese forces used massive biochemical weapons to break Chinese defenses. In November 1941, members of Unit 731 dropped plague-infested fleas from planes over Changde for the first time. In the epidemic that followed, 7,643 Chinese died. When Japanese troops attacked Changde in 1943 and encountered unexpectedly fierce resistance, they tried by all means to break this offensive, which lasted six weeks. Outbreaks of plague broke out during the battle, affecting both Chinese soldiers and civilians. According to several Japanese soldiers from Unit 731, including Shinozuka Yoshio , they had sprayed plague pathogens in the form of sprayable warfare agents from aircraft in and around Changde. At the same time, other army units, including unit 516 , began using chemical weapons on a massive scale . 50,000 Chinese soldiers and 300,000 civilians died in the course of the battle. How many of them were killed by the biological and chemical weapons cannot be determined. These missions and the experiments on people are counted among the Japanese war crimes .

From 1943, the susceptibility of European descent people to American prisoners of war was tested in order to prepare for the later use of biological weapons in the USA, for the transport of which balloon bombs had been developed by 1945 , which were supposed to reach North America via the jet stream .

Great Britain

After the discovery of bacteria and viruses as the cause of diseases, more targeted research was possible in the 20th century. During the Second World War , targeted experiments with pathogens were made in Great Britain, on the direct instructions of Winston Churchill , in order to further develop them as weapons. According to intelligence information, the allies assumed that Germany had anthrax and botulinum toxin , which is why Great Britain produced 1,000,000 vaccinations against botulinum toxin. However, this information later turned out to be incorrect. Germany also had little information about the Allied bioweapons program. Mainly the military and secret services received false reports. For example, the German secret services thought that Great Britain was planning to drop Colorado beetles over Germany.

In the course of British bioweapons trials, Gruinard Island , an uninhabited island in northwest Scotland, was contaminated with anthrax spores. In response to rumors that biological weapons were being developed in Japan / Germany , the pathogens had been tested for combat purposes and scattered over the exclusively animal-inhabited island to which an additional 60 sheep had previously been brought. Almost all of the fauna was completely destroyed within one day. This experiment was carried out in collaboration with the United States and Canada. Britain produced anthrax in large quantities as a biological weapon during World War II. The intention was to incorporate anthrax spores into animal feed as part of Operation Vegetarian and to throw this into agricultural areas in Germany. The USA decided to produce bioweapons for Great Britain because Great Britain would have been too vulnerable as a production location due to its proximity to Germany. In 1944 the US Army commissioned a million two-kilogram anthrax bombs to be dropped on Berlin, Hamburg, Stuttgart, Frankfurt, Aachen and Wilhelmshaven. However, due to a production delay, the war was won before it could come to that. Experts had estimated that around half of the population would die of anthrax in these bombings.

Germany

Germany itself was only marginally concerned with biological weapons during World War II. At the beginning of the war, the Wehrmacht was not interested in biological warfare because it considered it inefficient and unpredictable. In 1940, however, when the Germans marched into Paris, they discovered a research laboratory for biological warfare, which had been researching biological weapons since 1922 and a German research unit headed by the bacteriologist Heinrich Kliewe was now in operation. It was called " Department Kliewe " and dealt with, among other things, anthrax and plague pathogens . However, the experiment was discontinued when Hitler banned all German offensive biological research in 1942. This made the German Reich one of the few major powers participating in the war that complied with the Geneva Protocol on biological warfare.

Simultaneously with the ban on offensive bioweapons research, however, Hitler ordered that defensive bioweapons research be stepped up. In 1943 , for example, the “ Arbeitsgemeinschaft Blitzableiter ” was founded in order to develop defensive measures against biological weapons under the direction of Kurt Blome . In addition, from 1942 Blome was also responsible for setting up the Central Institute for Cancer Research in Nesselstedt near Posen , which, in addition to cancer research , was also intended for work on biological weapons from the start. The often immature vaccines intended for defense against biological weapons were often tested on concentration camp inmates. Research into offensive B warfare was also carried out behind Hitler's back, because the pathogens also had to be generated and tested for any defensive measures that might be required. Heinrich Himmler in particular was a great advocate of biological weapons. For example, he supported a proposal by Kliewe to contaminate food that is eaten uncooked with bacteria. It was not until February 1945 that Hitler had the consequences of Germany's withdrawal from the Geneva Conventions examined. Since in this case Germany might have fallen victim to a bio-attack by the Allies, Hitler decided not to leave.

After the end of the Second World War, Colorado beetles multiplied by leaps and bounds in Germany's Soviet occupation zone until almost half of the agricultural area was infested by 1950. The GDR leadership was unable to cope with the catastrophe, but used the plague for propaganda purposes during the Cold War by claiming that American planes were using American planes to use beetles as a biological weapon to sabotage socialist agriculture would be thrown off. From 1950 a campaign against the Amikäfer or Colorado beetle, called saboteurs in American services, was launched on posters and in numerous media reports. The same argument had already been used by the Nazi regime in World War II and claimed that the Colorado beetles had been dropped from American planes.

As a result, the US government demanded countermeasures from the Federal Republic of Germany. It was decided to send the mail to all the councils of the GDR municipalities and to release the balloon of potato beetle dummies made of cardboard with an "F" printed on it for "freedom".

United States

The United States was the last of the great powers to start its bioweapons program in World War II. It was not until 1941 that Henry L. Stimson , then Secretary of War, commissioned the National Academy of Sciences to conduct research on biological weapons defense. But this company was too small for serious biological weapons research, and after the attack on Pearl Harbor , the Department of War was hired to develop bi-weapons. In 1943 America produced botulinum toxin , anthrax and Brucella for the first time , and several other pathogens were tested for their suitability as a B-weapon. While only about 3.5 million US dollars were available at the beginning of the program, by the end of the war it was already 60 million.

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union began offensive research on biological weapons as early as 1926. The Soviet Union established one of the first research centers for biological weapons on Solovetsky Island in the White Sea. Allegedly, human experiments on prisoners are also said to have been carried out here. However, this information is controversial. There is evidence that the Soviet Union infected German troops with tularemia during World War II shortly before the Battle of Stalingrad . Within a week, thousands of people in the affected area contracted tularemia. The Soviets reported that this phenomenon was due to natural circumstances, such as poor hygiene. But while 10,000 tularemia cases occurred in the Soviet Union in 1941, there were already 100,000 in 1942. In 1943 the number of tularemia sufferers was back to 10,000. Another indication of a possible use of the pathogen is that the epidemic initially only broke out among the Germans and only later - probably due to a change in the wind direction or small animals that came through the fronts - among the Soviets. In addition, almost 70 percent of the victims contracted pulmonary entularemia, which is only caused by the spread of aerosols . Furthermore, the Soviet Union carried out research on the tularemia pathogen in 1941. Except for this incident, which was probably intended only as an experiment, there is no known use of biological weapons in World War II.

Cold War

It was not until 1946 that the American War Department issued a report that it was researching the development of biological weapons. The military had come across the records of the head of Unit 731 , Shirō Ishii , and some of them were used as a basis for research. Fort Detrick , the US bioweapons research center, was expanded in 1950 and another research facility was built at Pine Bluff . Bioweapons research was also intensified when the Korean War broke out in 1950 . Research was carried out, among other things, on infected mosquitoes, which were planned for a possible release in enemy areas . In September 1950, two U.S. submarines sprayed Serratia marcescens off the coast of San Francisco to find out how many residents would become infected. The bacterium is harmless to healthy people, but attacks immunocompromised people. There were deaths in hospitals that could be attributed to infection with the sprayed pathogens. During this time, Americans often did experiments by spreading pseudo-pathogens and measuring how far they spread. In the 1960s, for example, pathogens were tested in the New York subway system, infected birds were sent on journeys in the South Pacific, and pathogens were carried from towers and airplanes. In addition, weapons and projectiles were developed for the use of pathogens. They also found out how to spray dry agents, which are easier to disperse than wet agents in a kind of cloud of dust. Bioweapons have also been tried on people, mostly prisoners or minorities. In the 1970s, for example, there were biological weapons tests on 2,200 Adventists who refused to use weapons for reasons of conviction. A significant part of the tests carried out should still be in the dark. Only 2-3 CIA officers were initiated into the events in Fort Detrick, the work was hardly ever documented. There have been dangerous accidents at Fort Detrick, some of which are detectable. In 1981, for example, two liters of the Chikungunya virus were stolen - enough to kill the world's population several times. The fact came to light through indiscretion by a former employee.

During the Vietnam War in 1965, the Americans discussed the use of smallpox virus because their own troops were protected. But for fear of a counter-attack, this proposal was rejected. During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, too , the Americans planned to drop a mixture of different pathogens from airplanes over Cuban cities. However, the plan was never implemented. In 1965, the budget for bi-weapon research was constantly reduced until then-President Richard Nixon dissolved the bi-weapon program in 1969 . On the basis of this declaration, all bi-weapons were, at least officially, destroyed by the military. The research centers were either repurposed or closed. The destruction of the stocks lasted three years, until 1972. Shortly afterwards, the Biological Weapons Convention came into force. Contradicting this is a paper from a 1969 congress that showed the Pentagon's obvious interest in the development of new biological weapons. The need is justified with the rapid advances in the field of molecular biology and genetic engineering. For example, US $ 10 million was estimated to use genetic engineering to produce a pathogen that does not exist in nature and against which immunity cannot be acquired.

In 1950 there was a report that the potato beetle plague, which was rampant in the GDR at the time, was caused by the massive dropping of specially bred "Colorado beetles" by the Americans. This later turned out to be propaganda . Similar reports of crop damage or crop pests come from Cuba. However, these incidents could never be fully resolved.

According to official information, there was no research on biological weapons in the territory of the GDR . However, there was a section of military medicine at the Ernst Moritz Arndt University of Greifswald with L2 laboratories, to which funds from the Ministry of Defense also flowed. Intelligence information suggests that military research had also been carried out on the nearby island of Riems .

Soviet B-weapon research benefited from captured German researchers and engineers as well as captured records of research and experiments from Unit 731 after World War II . A new research center was built near Moscow, where research was carried out on tularemia, anthrax and botulinum, among other things. In 1973 the Soviet Union started a project called Biopreparat , which was carried out in several research centers and had around 50,000 employees; and that although the USSR had signed the biological weapons convention. After smallpox was declared to be eradicated in 1980, Russia conducted intensive research into the pathogens of this disease, since after the end of the mass vaccinations, people would be susceptible to the disease again after a few years. Like the USA, the Soviet Union continued to work on its biological weapons program under the guise of researching infectious germs, despite the signing of the Biological Weapons Convention and, in addition to some of the pathogens mentioned above, also researched hemorrhagic viruses such as Ebola and Marburg and some South American representatives such as Machupo (Bolivian hemorrhagic fever ) and Junin (Argentine hemorrhagic fever). In addition, they are said to have worked on an Ebola smallpox chimera . The center of Soviet research was the now abandoned city of Kantubek on the former island of rebirth in the Aral Sea . Several genetic engineering research facilities have been funded by the Department of Defense. These include the Research Institute for Military Medicine of the Ministry of Defense of the USSR in what was then Leningrad . Among other things, rabbit plague, typhoid fever and tetanus pathogens were worked on in L3 laboratories. Other research laboratories in question were located in Kirov , Moscow , Sverdlovsk and Ksyl-Orda (field test laboratory). On April 2, 1979 there was an anthrax accident in Sverdlovsk , in which anthrax spores were released into the area due to a defective ventilation system. On April 12, the Sverdlovsk area was quarantined. The KGB covered up this accident in a large-scale operation. He claimed the epidemic broke out through contaminated meat. It was not until 1992 that the Russian government under Boris Yeltsin confessed to the accident and its cover-up. At the end of the Cold War, two Soviet bioweapons researchers, Vladimir Passechnik and Ken Alibek , defected to the West and provided information about the Soviet bioweapons program . Alibek, who had been researching biological weapons since 1974, reported attempts to modify it with anthrax . These are said to have been successful in that the disease could be made resistant to antibiotics. The Soviet Union immediately developed a new antibiotic against it so that it could protect its troops. Alibek also reported on Soviet aircraft that were specially developed to spray germs.

Today the production and possession of biological weapons are prohibited worldwide by the Biological Weapons Convention (adopted in 1972, ratified by 183 states and entered into force in 1975). Research into countermeasures is permitted, however, and offers a loophole, as pathogens must also be bred for this purpose.

After the cold war

In 1983, the South African apartheid government started a bioweapons program called Project Coast , which was headed by Wouter Basson . Project Coast was officially a defensive program, but unofficially, methods were developed to murder people in secret, for example with bullets containing pathogens. Among other things, they worked on so-called ethnic weapons , which, for example, only made black Africans sick. It is not known how many people fell victim to the Project Coast bio-attacks.

Before the start of the Second Gulf War , the American army command feared that Iraq could use biological weapons, since it had already started a biological weapons program at the end of the First Gulf War . The Iraqi institutes received most of the pathogens from American or German companies. It later emerged that Iraq had actually produced over 19,000 weapons-grade liters of botulinum toxin, 8500 liters of anthrax and 2400 liters of aflatoxin , which were never used. The Iraqis did not master the processes to produce agents with which the pathogens could have been transmitted through the air. After the war, Iraq officially destroyed its bioweapons, but unofficially, individual institutes were able to carry out covert research and manufacture.

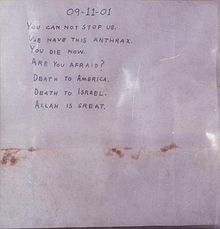

In 2001 there were several cases of illness and death from the release of anthrax and ricin from letters or parcels in Florida, New York, New Jersey and Washington. The main victims and targets were postal workers, journalists and politicians. The assassin was believed to be one of Fort Detrick's laboratory staff . No further public investigation results have been made known so far. Main article: 2001 anthrax attacks .

Situation today

The US research since 2002 in the field of "non-lethal" weapons, among other things, material destroying microbes, which does not explicitly against the BTWC (Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, the Biological Weapons Convention ) in violation because it biochemical the problem of "non-lethal" Weapons not dealt with so far.

Today, biological weapons are mainly considered to be potential weapons of mass destruction by terrorists (see: Bioterrorism ), as they are available everywhere (from nature) and are theoretically easy to manufacture, apart from the fact that the pathogens first have to be optimized for the use of weapons. Today, biological weapons are generally considered to be too unpredictable for military use. With the help of genetic engineering , bacteria have already been made antibiotic-resistant and, at the same time, a new antibiotic or a new vaccine has been developed to theoretically make it possible to use these pathogens in war and still protect one's own troops.

But it could also be possible to develop pathogens that would only be dangerous for people with certain genes , especially genes that only or mainly occur in a certain region. This could protect own troops from the disease, which could make biological weapons interesting again for both the military and terrorists. This special type of biological weapon is called an ethnic weapon , colloquially it is also referred to as biogenic weapons (from biological-genetic ). However, there are some arguments against the possibility of realizing ethnic weapons: Genetic differences within populations are often greater than the differences between different populations; furthermore, the effects of targeted delivery systems , which are required for the targeted use of pathogenic characteristics, have not yet been satisfactorily researched.

There are also many plant pathogens ( rust diseases , etc.) that can be used specifically against crops and animals.

The "dirty dozen"

Although around 200 potentially weaponized pathogens, toxins and biological agents are known, the CDC has compiled a list of the 12 pathogens that are most likely to be used in a biological weapon attack. These warfare agents are characterized either by their easy distribution, their simple transmission or just by their high lethality rate . Among them are bacteria, viruses, and toxins. Also known under the name " Dirty Dozen " is a list of globally banned organic toxins.

| Surname | Transmission from person to person possible | Incubation period or latency period | Mortality rate (untreated) | Countermeasures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| smallpox | Yes | 1-2 weeks | up to 90% | Vaccination |

| anthrax | no | 1-6 days | Depending on the type up to 80% | Antibiotics |

| pest | Yes | 1-3 days | Depending on the type up to 90% | Antibiotics |

| Tularemia | no | 2-10 days | up to 60% | Antibiotics |

| Brucellosis | no | 2-3 weeks | less than 5% | Antibiotics |

| Queensland fever | Yes | 9-40 days | under 2% | Antibiotics |

| snot | Yes | 1-14 days | up to 100% | Antibiotics |

| Encephaliticidal viruses | Yes | up to 1 week | up to 50 % | z. T. vaccination, but not against all viruses |

| hemorrhagic viruses | Yes | 4-21 days | Depending on the type up to 90% | none |

| Ricin | no | 1 day | up to 100% | none |

| Botulinum | no | up to 5 days | up to 90% | Antitoxin (antidote) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | no | 3–12 hours | Depending on the type up to 25% | Antibiotics |

See also

literature

- Ken Alibek, Stephen Handelman: Directory 15. Russia's Secret Plans for Biological Warfare . Econ, Munich 1999.

- Wendy Barnaby: Bioweapons - The Invisible Danger . Goldmann, 2002, ISBN 3-442-15197-X (Original title: The Plague Makers . Vision Paperbacks, London).

- Erik de Clercq: Handbook of viral bioterrorism and biodefense . Elsevier, Amsterdam 2003, ISBN 0-444-51326-4 .

- Rüdiger RE Fock et al .: Management of bioterrorist attacks with dangerous infectious agents . In: Federal Health Gazette - Health Research - Health Protection . tape 48 , no. 9 , September 2005, p. 1436-9990 .

- Erhard Geissler, Editor: Biological and Toxin Weapons Today - SIPRI -publication . Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, USA 1986, ISBN 0-19-829108-6 .

- Vlad Georgescu: REPORT: Iraq's secret suppliers. In: LifeGen.de. Retrieved October 11, 2006 .

- Kendall Hoyt, Stephen G. Brooks: A Double-Edged Sword: Globalization and Biosecurity. In: International Security. Volume 28, Number 3, Winter 2003/2004, pp. 123-148.

- Gregory Koblentz: Pathogens as Weapons. The International Security Implications of Biological Warfare. In: International Security. Volume 28, Number 3, Winter 2003/2004, pp. 84-122.

- Kathryn Nixdorff, Dagmar Schilling, Mark Hotz: How advances in biotechnology can be misused: Bioweapons . In: Biology in Our Time . tape 32 , no. 1 , 2002, p. 58-63 .

- Alexander Kelle, Kathryn Nixdorff: Are states losing control of their means of war? On the problem of biological weapons . In: Peace Report 2002 . LIT Verlag, Münster / Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-8258-6007-8 , p. 71-79 .

- Joshua Lederberg : Biological weapons - limiting the threat . MIT, Cambridge, Mass. 1999, ISBN 0-262-12216-2 .

- Achim Th. Schäfer: Bioterrorism and biological weapons . Köster, Berlin 2002, ISBN 978-3-89574-465-5 .

Web links

- Institute for Microbiology of the German Armed Forces

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Bioterrorism Agents / Diseases (English)

- Questionable bioweapons research in the US . Sunshine Project Germany, Dr. Jan van Aken

- Dr. Ken Alibek: Soviet B-weapon research

- Harvest-destroying biological weapons (PDF; 473 KiB)

- "Biological weapons became very attractive again" the GDR molecular biologist Erhard Geißler on the threat posed by biological weapons and the secret development of vaccines during the Cold War in: Berliner Zeitung , April 15, 2020

Individual evidence

- ↑ Harvest- destroying bio-weapons ( Memento from July 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 484 kB)

- ↑ Achim Schäfer: Bioterrorism and biological weapons . Hazard potential - hazard prevention. Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-89574-465-4 , p. 36.

- ^ Daniel Wortmann: From Hannibal to Bin Laden. Deutsche Welle, October 1, 2002, accessed November 19, 2008 .

- ↑ M. Wheelis: Biological warfare at the 1346 siege of Caffa . In: Emerging Infectious Diseases . tape 8 , no. 9 , 2002 ( cdc.gov ).

- ↑ Achim Schäfer: Bioterrorism and biological weapons, 2002, p. 20.

- ↑ sunshine-project.de: Biological weapons in the 21st century , conference on June 9, 2001 in Dresden.

- ↑ The secret history of anthrax - Declassified documents show widespread experimentation in '40s ( Memento from August 5, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ A b c d Kurt Langbein, Christian Skalnik, Inge Smolek: Bioterror. The most dangerous weapons in the world. Who owns them, what they do, how you can protect yourself . Stuttgart / Munich 2002, ISBN 3-421-05639-0 .

- ^ "Unmasking Horror" Nicholas D. Kristof (March 17, 1995) New York Times. A special report .; Japan Confronting Gruesome War Atrocity

- ↑ Unlocking a deadly secret ( Memento of November 24, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Photos of vivisection.

- ↑ Japan triggered bubonic plague outbreak, doctor claims ( Memento from December 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ A time-line of World War II , accessed May 2, 2008.

- ^ PBS Perilous Flight

- ^ Yuki Tanaka, Hidden Horrors , Westviewpres, 1996, p. 138.

- ↑ Vet refuses to take Unit 731 to his grave ( Memento of April 29, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), Japan Times , 2004.

- ↑ Japan prepared to use bio-weapons against the US , accessed June 25, 2010.

- ^ History of biological weapons - From well poisoners to World War II , On the history of biological weapons until 1945, Erhard Geißler , Dresden 2001.

- ↑ The secret of the killer bacteria . In: The mirror . No. 41 , 2000 ( online ).

- ↑ Jakob Segal / Lilli Segal: Aids - the trail leads into the Pentagon, together with Manuel Kiper, Biokrieg, Verlag Neuer Weg, 2nd supplemented edition October 1990, ISBN 3-88021-199-X , p. 140.

- ↑ Jakob Segal / Lilli Segal: Aids - the trail leads into the Pentagon, together with Manuel Kiper, Biokrieg, Verlag Neuer Weg, 2nd supplemented edition October 1990, ISBN 3-88021-199-X , p. 263.

- ↑ C. Piller, KR Yamamoto, Gene Wars, New York 1988.

- ↑ Hearings before the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respekt to Intelligence Activities of the United States Senate, Ninety-fourth Congress, Volume 1, Washington 1976, p. 6.

- ^ Dangerous viruses are gone, Frankfurter Rundschau , September 25, 1986.

- ↑ Achim Schäfer: Bioterrorism and biological weapons, 2002, p. 25.

- ^ Department of Defense Appropriations for 1970 Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations House of Representatives Ninety-first Congress, First Session 1969, Part 6, p. 129.

- ↑ Jakob Segal / Lilli Segal: Aids - the trail leads into the Pentagon, together with Manuel Kiper, Biokrieg, Verlag Neuer Weg, 2nd supplemented edition October 1990, ISBN 3-88021-199-X , pp. 283–284.

- ^ Smallpox, plague and Ebola as perfidious biological weapons

- ↑ Technology Review: Biowaffen I: Deadly Knowledge , December 27, 2006.

- ↑ crimelibrary.com: Apartheid: Biological and Chemical Warfare Program ( Memento of August 8, 2003 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ SPIEZ LABORATORY - Documentation - Background information - The B-weapons problem ( Memento from November 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Research on “non-lethal” weapons in the USA , Genetically Manipulated Microorganisms for the Destruction of Materials, The Sunshine Project, 2002.

- ↑ Ethnically Specific Biological Weapons , The Sunshine-Project, 2003.

- ↑ Science magazine " fu ndiert" of the Free University of Berlin : Possible dangers from bioterrorism , accessed on June 27, 2010.

- ↑ gifte.de: Staphylococcal enterotoxin B