Brucellosis

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| A23 | Brucellosis |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The Brucellosis is an infectious disease caused by the gram-negative , aerobic rod-shaped bacteria of the genus Brucella (also called bacteria Bang ) is caused. Brucellosis, which is characterized by undulating (undulating) fever ( Febris undulans , undulating fever) occurs in both animals and humans.

Depending on the causing brucellosis species, brucellosis are referred to as

-

Mediterranean fever or Malta fever caused by Brucella melitensis

(mainly found in goats, camels, and sheep) -

Bang's disease , Bang's disease , Bang's disease or abortion Bang (by Bernhard Laurits Frederik Bang ) caused by Brucella abortus

(mainly occurring in cattle) -

Swine brucellosis , caused by Brucella suis , and canine brucellosis , caused by Brucella canis

(only rare in humans)

Brucellen

→ Main article Brucellen

The causative agents of brucellosis are bacteria of the genus Brucella . Brucelles are gram-negative , very small, cocoid , pleomorphic aerobes .

classification

Of all types of Brucella, four are of human pathogenic importance and occur worldwide:

- Brucella abortus causes bovine brucellosis , also known as Bang's disease

- Brucella canis causes canine brucellosis

- Brucella melitensis causes sheep and goat brucellosis and, in humans, Malta fever (also known as Mediterranean fever)

- Brucella suis causes swine brucellosis , reindeer brucellosis (biovar 4) and hare brucellosis

Non-human pathogenic species:

- Brucella ovis causes epididymitis in rams

Types of unknown pathogenicity:

- Brucella ceti has been detected in whales

- Brucella neotomae was at a species of rat in the western United States demonstrated

- Brucella microti was detected in one type of mouse ( Microtus arvalis )

- Brucella pinnipedialis has been detected in seals

- Brucella inopinata has never been detected in animals and so far only in one person

- Brucella papionis has been detected in baboons

- Brucella vulpis was detected in a red fox ( Vulpes vulpes )

Transmission and Pathogenesis

Brucellosis is one of the anthropozoonoses . Infected animals that come into close contact with humans (cattle, goats, sheep, pigs, horses and rarely dogs) are transmitted to humans. In the Middle East, in the area between Iran, Somalia and Tunisia, 2–15% of all camels have antibodies against brucellosis ( Brucella melitensis , mostly serovars 2 and 3), which indicates a previous or current infection. Unpasteurized camel milk has been described repeatedly as a mechanism of transmission.

Brucella can survive in unpasteurized milk and cheese made from it for several weeks; this survivability results in the main route of infection. For farmers and veterinarians , infected animals (faeces, urine) can be a source of infection. If an infection is detected, there is an immediate notification obligation according to the IfSG .

Human-to-human transmission is very rare, but it can occur while breastfeeding . Transmission through sexual intercourse or blood transfusions only occurred in isolated cases.

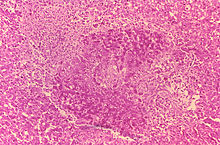

When the pathogen enters via the mucous membranes (e.g. upper digestive tract or respiratory tract ), an uncharacterized and unspecific inflammatory reaction occurs. After phagocytosis of the pathogen by granulocytes , in which they can survive, they are transported by the granulocytes to the local lymph nodes . From there, Brucella can spread via the blood ( hematogenous ) and spread in the organism. In the affected tissue, the infected organism tries to isolate the pathogen by forming typical, non-casing granulomas and to limit further infection.

Clinical course, diagnosis and symptoms

Up to 90% of the infections are subclinical and have only a slightly disturbed general condition. The infection can be caused by a direct cultivation of the pathogen z. B. detect in the blood culture , also Brucella-specific antibodies can be an indication of an acute infection (but also indicate a previous infection). However, direct pathogen detection on culture plates often only becomes positive late, so that an incubation of more than the usual five days is often necessary. Depending on the location of the infection process, blood, liquor , bone marrow , urine or tissue samples are taken. Cultures usually have to be repeated.

The incubation period is between two and three weeks for acute courses, up to several months for latent diseases.

The main symptom is fever, often with night sweats , chills, and nausea. In acute cases, the fever lasts for one to three weeks, but is interrupted by fever-free intervals. This has led to the name Febris undulans ("wavy fever"). In chronic illnesses, the fever can last for months. Liver and spleen swelling is found in a third of all patients .

The most common focal organ manifestations are bone and joint infections . The sacroiliac joint is most frequently affected in children , whereas in adults there is more likely to be bacterial inflammation of the intervertebral discs ( spondylodiscitis ), with the lumbar spine being affected in 60% and mostly the vertebrae LWK 4 and LWK 5 involved. In the X-ray image , changes often show only after two to eight weeks, which is the neighboring mainly to erosion of the cover and base plate vertebrae comes in the front area. The infection usually progresses slowly with local acute pain, neurological abnormalities are found in 43% and vertebral deformities occur in 7%. Due to the slow course, ossification (perilesional spondylophytes ) forms around the focus of the infection .

Further organ manifestations are in 10% urogenital inflammations, e.g. B. an inflammation of the testicles . Heart valve inflammation develops in less than 2% . Meningitis or pneumonia are very rare . The local inflammation is usually granulomatous and can be similar to that of tuberculosis .

Many acute courses of the disease heal spontaneously, only 5% of patients suffer a relapse . These relapses can occur up to two years after the initial illness. In addition, there is also protracted chronic inflammation with often unspecific symptoms, including psychological changes such as affect lability, depression or insomnia.

therapy

The gold standard is antibiotic therapy with doxycycline for 6 weeks and streptomycin for 2–3 weeks, and for chronic courses for up to six months. An alternative is the combination of doxycycline with rifampicin . Co-trimoxazole and rifampicin can be used in pregnant women and children . However, even after antibiotic therapy has been carried out, a relapse or an organ manifestation is still possible. According to Abele-Horn, the first-line therapy consists of the administration of doxycycline and rifampicin (alternatively streptomycin or gentamicin), the second-line therapy consists of cotrimoxacol and doxycycline (alternatively rifampicin or streptomycin), the treatment of severe infection consists of the administration of doxycycline, rifampycin and streptomycin (alternatively, gentamicin) Cotrimoxacol) and long-term therapy could be done with doxycycline and ciprofloxacin.

vaccination

There are two live vaccines for use in veterinary medicine - but since Germany is considered brucellosis-free (although 36 cases in people in 2016, 41 cases in 2017, 37 cases in 2018 and 35 cases in 2019), they are not used there.

Reporting requirement

In Germany, the direct or indirect detection of Brucella sp. Specifically notifiable in accordance with Section 7 of the Infection Protection Act (IfSG), provided that the evidence indicates an acute infection. The obligation to notify exists primarily for laboratories ( § 8 IfSG).

In Austria, Bang`sch [e] disease is a notifiable disease in accordance with Section 1 (1) of the 1950 Epidemic Act . The obligation to notify relates to cases of illness and death. Doctors and laboratories, among others, are obliged to report this ( Section 3 Epidemics Act).

In Switzerland, reporting requirements for brucellosis in terms of a positive laboratory analytical finding by the attending physician. In addition, if the laboratory results are positive for the pathogen Brucella spp. by the testing laboratory. This results from the Epidemics Act (EpG) in conjunction with the Epidemics Ordinance and Annex 1 or Annex 3 of the Ordinance of the FDHA on the reporting of observations of communicable diseases in humans .

history

Mediterranean fever (Latin febris melitensis , also called Malta fever and wave fever, Latin febris undulans ) was possibly already known at the time of Hippocrates . The English military doctor David Bruce was able to isolate the pathogen causing the Maltese fever Brucella melitensis in 1887 from the spleen of a soldier who died of an undulating fever . The bacterium was named after him as the discoverer. In humans, Bang's disease, the causative agent of which the Danish veterinarian Bang discovered in 1896, and its etiological connection with the “epidemic calving” in cattle was first established in 1925.

literature

- Marianne Abele-Horn: Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich, 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , p. 187 f.

- Hans von Kress (ed.): Müller - Seifert . Pocket book of medical-clinical diagnostics. 69th edition. Published by JF Bergmann, Munich 1966, p. 1062.

- Karl Wurm, AM Walter: Infectious Diseases. In: Ludwig Heilmeyer (ed.): Textbook of internal medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955; 2nd edition ibid 1961, pp. 9-223, here: pp. 146-148 ( brucellosis ).

See also

Web links

- Brucellosis - information from the Robert Koch Institute

Individual evidence

- ↑ Other names: Gibraltar fever , Neapolitan fever and Febris undulans melitensis .

- ↑ Textbook of Sheep Diseases, p. 221, online

- ↑ Other names: Febris undulans abortus Bang and Brucellosis Bang .

- ^ Fertility disorders in female cattle, Georg-Thieme-Verlag, p. 269, online

- ↑ Short textbook medical microbiology and immunology, p. 60 online

- ^ A b Peter Reuter: Springer Lexicon Medicine. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2004, ISBN 3-540-20412-1 , p. 307.

- ↑ a b Mark S. Drapkin, Ravi S. Kamath, Ji Y. Kim: Case 26-2012: A 70-Year-Old Woman with Fever and Back Pain New England Journal of Medicine 2012; Volume 367, Issue 8 of 23 August 2012, pp. 754-762

- ↑ Marianne Abele-Horn (2009), p. 187 f.

- ↑ Georg Sticker : Hippokrates: The common diseases first and third book (around the year 434-430 BC). Translated, introduced and explained from the Greek. Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig 1923 (= Classics of Medicine. Volume 29); Unchanged reprint: Central antiquariat of the German Democratic Republic, Leipzig 1968, p. 107 f.

- ↑ Karl Wurm, AM Walter: Infectious Diseases. In: Ludwig Heilmeyer (ed.): Textbook of internal medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955; 2nd edition, ibid. 1961, pp. 9-223, here: pp. 146-148 ( Bang's disease ).