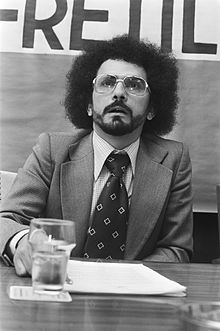

José Ramos-Horta

José Manuel Ramos-Horta (born December 26, 1949 in Dili , Portuguese Timor ) is an East Timorese politician. For his efforts to find a peaceful solution to the East Timor conflict, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1996 together with Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo . From 2006 to 2007 Ramos-Horta was Prime Minister of East Timor and from May 20, 2007 to May 20, 2012 he was the President . He was seriously injured in an attack on February 11, 2008 . On January 1, 2013, Ramos-Horta was appointed UN special envoy for Guinea-Bissau . From 2017 to 2018 Ramos-Horta was Minister of State and advisor on national security issues.

biography

Early years

José Ramos-Horta was born in Dili, the capital of East Timor, to the Timorese Natalina Ramos Filipe Horta from Holarua and the Portuguese Francisco Horta . Francisco Horta had been banished from his homeland by the dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar . Ramos-Horta's father was a non-commissioned officer in the Portuguese Navy in 1936 and participated in the mutiny of the Tagus warships . Together with other sailors, he took over two warships (the Aviso Afonso de Albuquerque and the destroyer Dao ) and set course for Spain to fight Francisco Franco on the side of the Republic in the Spanish Civil War . At the mouth of the Tejo, the mutineers were fired from land by Portuguese forces and had to surrender. Francisco Horta was exiled to Portuguese Timor. During the Second World War, he fought against the Japanese occupiers together with Australian commandos . He died in 1970. Ramos-Horta's grandfather António Luís Horta was also in political exile in the Azores , later on Cape Verde and in Portuguese Guinea , until he finally came to Portuguese Timor. José Ramos-Horta went to the Catholic Mission Missão do Sagrado Coração de Jesus in Soibada and the Liceu Dr. Francisco Machado to school in Dili . In his final year of school, Ramos-Horta was already working for the newspaper A Voz de Timor . Ramos-Horta also wrote political articles for the Seara magazine of the Diocese of Dili .

From 1970 to 1971 he had to go into exile in Portuguese East Africa (today's Mozambique ). The Direção-Geral de Segurança (DGS), the Portuguese secret police, had reported that Ramos-Horta had told an American tourist that Portugal was unable to develop Timor and that it would be better if the US took over the colony. Other sources indicate that an anti-colonial comment in the A Voz de Timor led to the banishment. Even in exile, Ramos-Horta was under surveillance by the DGS. Back in Timor, he wrote the article The Myth and Reality , which brought him back into the crosshairs of the police. The Carnation Revolution in Portugal in 1975 preceded another exile.

On August 23, 1973, the Australian journalist Bill Nicol first reported on an underground political movement called the "Timor Liberation Front" . According to a “young radical” from Dili, this movement is “insignificant, disorganized and unarmed”, but ready to take action against the Portuguese. Nicol is certain that the “young radical” was José Ramos-Horta. A few months later, Ramos-Horta also appears by name in the Australian press for the first time when he attacked Portuguese colonialism and the policy of the Australian Labor government in an interview. Instead of Australia's abstention on colonial issues in the United Nations , Ramos-Horta called for support for Timor in the form of development aid and training. In his homeland, Ramos-Horta got into trouble because of the interview, which is why he tried to distance himself a little from the interview with articles in the Voz de Timor.

The Timorese nationalists tried to find support for independence from Portugal in Indonesia, among other places. Ramos-Horta served as a liaison with Indonesia's consul in Dili, EM Tomodok . This encouraged Ramos-Horta to look for sympathizers with the Indonesian military.

In 1974 Ramos-Horta threatened to be exiled again because of his interview for the Australian Northern Territory News , but only two days before his planned departure, the news of the Carnation Revolution arrived in Portugal. After the end of the dictatorship, Ramos-Horta was able to stay in East Timor.

Struggle for independence

Ramos-Horta was one of the co-founders of the Associação Social Democrática Timorense ( ASDT , German Timorese Social Democratic Association , today's ASDT is a later foundation), from which FRETILIN later emerged. As a moderate politician in the nationalist leadership, he was intended as Foreign Minister of the government of the Democratic Republic of East Timor , which was proclaimed by FRETILIN in November 1975. Ramos-Horta held office in this capacity only a few days before Indonesia occupied East Timor. Ramos-Horta had left East Timor three days before the invasion to appeal to the UN Security Council for recognition of the country. Now he tried to urge him to take measures against the occupation and later against the mass murder of the Indonesian military in New York . In 1977 Ramos-Horta officially handed over his post as Foreign Minister to Marí Alkatiri to act as spokesman for the government in exile.

From 1976 to 1986 José Ramos-Horta was the permanent representative of FRETILIN at the United Nations and fought for the independence of East Timor. He was also the official spokesman for Xanana Gusmão , who led the armed struggle against the Indonesian troops and who was elected the first president of East Timor after the country's independence in 2002. Through his work, José Ramos-Horta became the best-known international advocate for the freedom of East Timor. In his homeland, he lost his sister Maria , who was killed in an air raid, and his two brothers Nuno and Guilherme , one of whom died during a police interrogation and the other disappeared without a trace at the age of 14, António died in November 1992 due to poor medical care.

Ramos-Horta studied international law in 1983 at the Hague Academy for International Law and Human Rights at the International Institute of Human Rights in Strasbourg. In the same year he took courses in American Foreign Policy at Columbia University in New York . Ramos-Horta graduated from Antioch University in 1984 with a Master of Arts degree in Peace Studies . He is a senior associate member of St Antony's College of Oxford University (1987). In 1988 Ramos-Horta left FRETILIN in order to be able to act impartially in the newly established umbrella organization of the East Timorese resistance CNRT .

Ramos-Horta worked for a time as a lecturer at the University of New South Wales in Sydney . In December 1996, José Ramos-Horta shared the Nobel Peace Prize with fellow countryman Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo . The committee recognized the two for their "constant efforts to stop the oppression of the common people" and hoped that this award would "spur efforts to find a diplomatic solution to the East Timor conflict based on the right to self-determination".

Political career in independent East Timor

When the United Nations took over administration in East Timor in 1999, Ramos-Horta returned to his homeland on December 1 and became Foreign Minister of the transitional government on July 12, 2000 . After independence, Ramos-Horta remained the country's foreign minister. After the defense minister's resignation on June 3, 2006 in the course of the unrest in East Timor 2006 , Ramos-Horta also took over his duties, but resigned from all his offices on June 25, 2006 as a result of conflicts with the controversial Prime Minister Marí Alkatiri, after FRETILIN Alkatiris had refused a dismissal. Alkatiri gave up a day later and also resigned. José Ramos-Horta continued to run the government. He was traded as the preferred candidate of the West for the successor to Alkatiris. Parts of FRETILIN favored Ramos-Horta's ex-wife and Minister of State Ana Pessoa Pinto, who was a close confidante of Alkatiris. Finally, on July 8, 2006, President Xanana Gusmão declared that he had agreed with FRETILIN to make Ramos-Horta Prime Minister. On July 10th he took his oath of office as the new head of government. Ramos-Horta's deputy became Minister of Agriculture Estanislau da Silva and Minister of Health Rui Maria de Araújo . Ramos-Horta also served as Minister of Defense.

In the presidential elections on May 9, 2007 , Ramos-Horta was elected president with 69% after a runoff against the FRETILIN candidate Francisco Guterres . Predecessor Xanana Gusmão had already announced in advance that he no longer wanted to run, but would run for the new head of government in the following parliamentary elections. Ramos-Horta was supported during his candidacy by the new parties CNRT (the Gusmãos party), PMD , UNDERTIM and the Marine youth organization .

On May 19, 2007, Ramos-Horta resigned from his offices as Prime Minister and Minister of Defense and was sworn in as the new President of East Timor on May 20, 2007.

On February 11, 2008, rebels attacked the house of Ramos-Horta. Ramos-Horta was seriously wounded by two shots. The leader of the rebels, Alfredo Reinado , was killed in the attack.

After Ramos-Horta repeatedly criticized politics and possible corruption in the Gusmãos government, the latter refused to support him in the 2012 presidential election . Instead, Gusmão supported the independent candidate Taur Matan Ruak . Ramos-Horta was eliminated in the first round of the elections on March 17, 2012, clearly trailing in third place, with only 17.48%. On the night of May 19-20, Ramos-Horta gave up his position at midnight to his successor, Taur Matan Ruak.

On September 15, 2017, under the re-appointed Prime Minister Alkatiri, Ramos-Horta was appointed Minister of State and Adviser on National Security Issues in the Seventh Government of East Timor . Ramos-Horta remained in office until the eighth government of East Timor took office on June 22, 2018.

Ramos-Horta and the United Nations

In February 2006 it was announced that Ramos-Horta was being considered by the UN Security Council to succeed UN Secretary General Kofi Annan . “I'm not a candidate yet, but I'll think about it. I have considerable support, my possible candidacy would meet the expectations of millions of people around the world, ”said Ramos-Horta.

After Ramos-Horta was sworn in as Prime Minister of East Timor on July 10, 2006, he said in his inaugural address that he did not want to become UN Secretary General for the time being:

“In conclusion, until some weeks ago friends and supporters made me believe and wanted me to believe that I could occupy the 38th floor of United Nations Head Quarters. Some friendly governments believed in my eligibility. I have got another mission here. I would never be a good United Nations Secretary General if I was not a good Timorese first and a good Timorese must be in this country with his people in their moments of crisis. Perhaps then in 2012. Now the world has to wait as I have more pressing needs to attend to in Timor-Leste. "

“Finally, because a few weeks ago friends and supporters made me believe and let me understand that I could use the 38th floor of the United Nations Headquarters. Some governments friend of mine thought I was eligible. I have another job here. I would never be a good Secretary-General of the United Nations if I were not a good Timorese first, and a good Timorese must stay in this country and assist his people in the moment of crisis. Perhaps 2012. Now the world has to wait as I have more urgent duties to fulfill in Timor-Leste. "

Instead of Ramos-Horta, the South Korean Ban Ki-moon became the new UN Secretary General.

In June 2008 Ramos-Horta was traded as a promising candidate for the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights . He decided, however, not to accept the office, as he feared renewed unrest in East Timor through the early election of a new head of state that would then be necessary.

After the end of his presidency, Ramos-Horta was appointed by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on January 1, 2013 as the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Guinea-Bissau. He succeeded Joseph Mutaboba from Rwanda , who ended his term on January 31st. On August 21, 2015, the Nigerian Olusegun Obasanjo took over from Ramos-Horta.

Private life

Ramos-Horta is divorced. He has a son with his former wife, Attorney General Ana Pessoa Pinto . Loro Horta , who was born in 1977, studied at Sydney University and the People's Liberation Army National Defense University in Beijing . He has been East Timor’s Ambassador to Cuba since 2016. Ramos-Horta's sister Rosa was married to João Viegas Carrascalão , head of the União Democrática Timorense (UDT), until his death in 2012 .

Ramos-Horta has been President of the Boavista Futebol Clube Timor-Leste since 2018 .

Publications

- Funu: the Unfinished Saga of East Timor . Red Sea Press, New Jersey 1987, ISBN 0-932415-15-6

- Funu. East Timor's struggle for freedom is not over! Ahriman, Freiburg im Breisgau 1997, ISBN 3-89484-556-2

- Mundu ne'ebe lakon ona , 2009, a book about the children of East Timor

Awards

- 2014 - Companion of the Order of Australia

- 2014 - Ordem Nacional Colinas do Boé - Guinea-Bissau

- 2013 - Honorary Companion of the Order of Australia

- 2010 - José Martí Order - Cuba

- 2008 - Great Order of the Collar of the Order of Infante Dom Henrique , Portugal

- 2004 - Grand Cross of the Order of Rio Branco, Brazil

- 2001 - Hollywood Film Festival Humanitarian Award, USA

- 2002 - Golden Plate Award, Academy of Achievements, USA

- 2000 - Gold Medal of the President of Italy

- 1999 - First Hague Peace Appeal Award, The Netherlands

- 1998 - Gold Medal from the University of Coimbra, Portugal

- 1998 - Grand Cross of the Order of Freedom, Portugal

- 1997 - Medal from the University of San Francisco, USA

- 1996 - Nobel Peace Prize , Norway

- 1996 - First UNPO Peace Prize, Netherlands

- 1995 - International Peace Activist Award, Gleitsman Foundation, USA

- 1993 - Thorolf Rafto Memorial Prize , Norway

See also

Web links

- Literature by and about José Ramos-Horta in the catalog of the German National Library

- Website of José Ramos-Horta (English)

- Biography of Ramos-Horta on the government website ( Memento of May 29, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1996 award to José Ramos-Horta (English)

- Lindsay Murdoch, Horta vows to rebuild Timor , article in the Australian newspaper The Age , July 10, 2006

- Frankfurter Rundschau: "I'm not a hero", March 10, 2012 - José Ramos-Horta on his life after the attack

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Official biography on the President's website. (PDF) (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; Retrieved April 26, 2014 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ^ John Pilger: Hidden Agendas , 2010, ISBN 1-4070-8641-3

- ↑ Sara Niner: Xanana Thesis Chapter 1: 1946-78 , p. 10, accessed June 9, 2017.

- ↑ a b "Part 3: The History of the Conflict" (PDF; 1.4 MB) from the "Chega!" Report of the CAVR (English)

- ^ Antero Bendito da Silva, Robert Boughton , Rebecca Spence: FRETILIN Popular Education 1973-1978 and its Relevance to Timor-Leste Today , University of New England, 2012, accessed June 5, 2019.

- ↑ a b José Ramos-Horta: Funu. East Timor's struggle for freedom is not over! Ahriman-Verlag, Freiburg 1997, ISBN 3-89484-556-2

- ^ Herald Sun, February 12, 2008, Australia to send East Timor rescue force

- ^ NASDAQ, February 13, 2008, E Timor President Could Be Home In 3 Weeks, Say Doctors -AFP

- ↑ SAPO: VII Governo constitucional de Timor-Leste toma hoje posse incompleto , September 15, 2017 , accessed on September 15, 2017.

- ↑ Address by Dr José Ramos-Horta at his swearing in ceremony as Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste. Cabinet Office of the Minister for Foreign Affairs and Cooperation, Timor-Leste, July 10, 2006, accessed January 28, 2016

- ↑ Tages-Anzeiger, June 27, 2008, Ramos-Horta but not UN commissioner ( Memento from June 27, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Reuters: UN chief names East Timor's Ramos-Horta envoy to Guinea-Bissau , January 1, 2013 , accessed on January 1, 2013

- ↑ PM News: Buhari appoints Obasanjo as Special Envoy to Guinea Bissau , accessed on September 15, 2017.

- ↑ O Jogo: Boavista anuncia filial em Timor Leste , March 20, 2018 , accessed on March 21, 2018.

- ↑ SBS: Australia honors former East Timor President Ramos-Horta , September 7, 2014 , accessed September 7, 2014.

- ↑ ramoshorta.com: Mais alta condecoração para Ramos-Horta. Archived from the original on June 20, 2014 ; Retrieved June 20, 2014 .

- ↑ Winner of the Rafto Prize , on the Rafto Foundation website, accessed on April 22, 2018.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ramos-Horta, José |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ramos Horta, José |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | East Timorese politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 26, 1949 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Dili , Portuguese Timor |