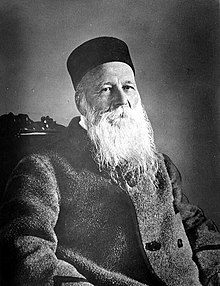

Henry Dunant

Henry Dunant [ ɑ̃ˈʁi dyˈnɑ̃ː ], actually Jean-Henri Dunant (born May 8, 1828 in Geneva , † October 30, 1910 in Heiden ), was a Swiss businessman and a humanist with a Christian background. During a business trip , he was in June 1859 in the vicinity of the Italian town of Solferino witnessed the appalling conditions among the wounded after a battle between the Austrian army and the troops of Sardinia-Piedmont andOf France . He wrote a book about his experiences with the title A Memory of Solferino , which he published in 1862 at his own expense and distributed in Europe.

As a result, a year later the International Committee of Aid Societies for the Care of the Wound was founded in Geneva , which has been known as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) since 1876 . The Geneva Convention , passed in 1864, is essentially based on suggestions from Dunant's book. Henry Dunant, who then lived in poverty and oblivion for around three decades due to business problems and his subsequent exclusion from Geneva society, is considered to be the founder of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement . In 1901 he and the French pacifist Frédéric Passy received the first Nobel Peace Prize for his life's work .

Life

1828–1859: youth and business

Parental home and education

Henry Dunant was born on May 8, 1828 in Geneva, the first son of Antoinette Dunant-Colladon and her husband, the merchant Jean-Jacques Dunant, into a very pious Calvinist family. His parents' house is in Geneva at Rue Verdaine 12. His parents had great influence in Geneva and were politically and socially involved. The father was a member of the Conseil Représentatif, the legislature of the city of Geneva at the time, and looked after orphans and convicts . Henry Dunant's mother was a daughter of Henri Colladon, director of the Geneva hospital and mayor of Avully near Geneva. In the charitable field, she was mainly active for the poor and the sick. One of Henry Dunant's maternal uncle was the physicist Jean-Daniel Colladon .

The charitable activities of the parents were reflected in the upbringing of their children: Henry Dunant, his two sisters and two brothers were encouraged to take on social responsibility at an early age. A trip to Toulon with his father was formative for Henry Dunant , where he had to watch the tortures of galley prisoners. Apart from that, little is known about his childhood in his own memoirs. Due to poor grades, Henry Dunant left the Collège de Genève prematurely and began a three-year apprenticeship with the money changers Lullin and Sautter in 1849 . After successfully completing his training, Dunant remained employed in the bank.

Christian commitment

Henry Dunant's Christian faith was shaped by the Geneva theologian Louis Gaussen , who founded the Société Evangélique de Genève in 1831 and attended Dunant's Sunday school as a teenager. The Société Evangélique was a parish that also included his mother, his father's sister, and his own sister Marie. With the desire to get socially involved, Henry Dunant, under the influence of the Réveil , a revival movement of the 19th century in Geneva and other French-speaking regions, joined the Geneva Société d'Aumônes (Society for Alms Giving ) at the age of 18 . In the following year, he and friends founded the so-called “Thursday Association”, a loose association of young people who met in the premises of the Société Evangélique for Bible studies and supported hungry and sick people together.

Henry Dunant spent most of his evenings and Sundays visiting prisoners and helping poor people. From an early age he was considered gifted at inspiring other people for a common goal and motivating them to follow him in his activities. Animated by a stay of the revival preacher Adolphe Monod in the Thursday Association, he founded a Geneva group of the Christian Association of Young Men (YMCA) on November 30, 1852 , in which he acted as secretary. Three years later he was instrumental in founding the Young Men's Christian Association in Paris. In the Evangelical Alliance , which spread out from England in 1846 and contributed to the formation of the YMCA groups in various countries, Dunant was one of the fifteen founders of the Swiss Evangelical Alliance in 1847 . He became her secretary in 1852 at the age of 24 and was in charge of her until 1859.

Business in Algeria

In 1853, Dunant visited Algeria , Tunisia and Sicily on behalf of the "Geneva Trading Company of the Swiss Colonies of Setif" (French Compagnie genevoise des Colonies Suisses de Sétif ) . Despite little experience, he carried out the business of his clients successfully. Inspired by his travels, Dunant wrote his first book, Notice sur la Régence de Tunis , which appeared in 1858. With the help of this book he was able to gain access to several scientific societies.

In 1856 he founded a colonial company and, after he had acquired a land concession in French-occupied Algeria, two years later under the name "Financial and Industrial Company of the Mills of Mons-Djémila" (French Société financière et industrial des Moulins des Mons- Djémila ) near the Roman ruins of Djémila a mill shop. The land and water rights were not clearly regulated, however, and the responsible colonial authorities did not behave cooperatively. In 1858, Dunant took on French citizenship in addition to his Swiss citizenship in order to facilitate access to land concessions from the colonial power France in Algeria.

A year later he decided to contact Emperor Napoléon III directly . when he was with his army in Lombardy . There France fought on the side of Sardinia-Piedmont against the Austrians, who had occupied large parts of what is now Italy. Napoleon's headquarters were in the small town of Solferino near Lake Garda. Dunant wrote under the title The Restored Empire of Charlemagne, or the Holy Roman Empire, Renewed by His Majesty the Emperor Napoleon III. a flattering eulogy for Napoleon III, in order to give him a positive attitude towards his concerns. He then went on a trip to Solferino to meet the emperor there personally.

1859–1867: The Red Cross and the Geneva Convention

Battle of Solferino

→ Main article: Battle of Solferino

On the evening of June 24, 1859, Dunant came after the end of a battle between the troops of Sardinia-Piedmont and France under the leadership of Napoleon III. on the one hand and the army of Austria on the other past the battlefield near Solferino. There were still around 38,000 wounded, dying and dead on the battlefield without anyone to help them. Deeply shocked by what he saw, he spontaneously organized the makeshift care of the wounded and sick soldiers with volunteers from the local civilian population , mainly women and girls. In the small town of Castiglione delle Stiviere in the immediate vicinity of Solferino, he and other helpers set up a makeshift hospital in the Chiesa Maggiore, the largest church in town. About 500 of the 8,000 to 10,000 wounded who had been brought to Castiglione were cared for here.

As he quickly discovered, there was a lack of almost everything: helpers, specialist knowledge, medical material and food. Dunant and the helpers who responded to his call made no distinction between the soldiers in terms of their nationality in their assistance. The slogan “Tutti fratelli” (Italian: all are brothers ) of the women of Castiglione became famous for this attitude . Dunant also succeeded in getting Austrian army doctors captured by the French released to take care of the injured. He set up makeshift hospitals and had bandages and relief supplies brought in at his own expense. Despite the help, many wounded died.

Foundation of the Red Cross

Under the influence of these events, Dunant returned to Geneva in early July . On the advice of his mother, he initially spent a month in the mountain hut of a family friend in Montreux . He then traveled to Paris for several weeks. For his work in Solferino in January 1860, together with the Geneva doctor Louis Appia , he received the Order of Saint Mauritius and Lazarus from the Sardinian King Victor Emanuel II , later the second highest honor of the Kingdom of Italy .

At the beginning of 1860 he first tried to improve the financial situation of his ventures in Algeria, but did not succeed. Furthermore, since he could not forget what he had experienced in Solferino, he began to write a book entitled Un souvenir de Solferino (" A Memory of Solferino "). In it he described the battle, the suffering and the chaos in the days after the battle. In addition, in this book he developed the idea of how the suffering of the soldiers could be reduced in the future: on a basis of neutrality and voluntariness, aid organizations were to be founded in all countries that would take care of the wounded in the event of a battle. In September 1862 he had the book printed at his own expense by the Geneva printing company Fick in a print run of 1,600 copies and then distributed it to many leading figures from politics and the military throughout Europe.

Dunant then went on trips across Europe to promote his idea. His book was received almost unanimously positively and with great interest and enthusiasm, it received recognition and sympathy. A second edition was printed in December 1862, and at the beginning of the following year, translations into English, German, Italian and Swedish appeared alongside a third. One of the few negative reactions was the statement by the French Minister of War Jacques-Louis Randon that the book was directed "against France". On the other hand, Florence Nightingale was also surprisingly critical, as she was of the opinion that the aid societies proposed by Dunant would take on a task that was the responsibility of the governments.

The Geneva Public Benefit Society's president , lawyer Gustave Moynier , made the book and Dunant's ideas the subject of the Society's General Meeting on February 9, 1863. Dunant's suggestions were examined and judged by members to be useful and feasible. Dunant himself was appointed a member of a commission that also included Gustave Moynier, General Guillaume-Henri Dufour and the doctors Louis Appia and Théodore Maunoir . During the first session on February 17, 1863, the five members decided to convert the commission into a permanent body. This day is considered to be the founding date of the International Committee of Aid Societies for the Care of the Wound , which has been called the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) since 1876 . Dufour was named first president, Moynier became vice-president and Dunant became secretary of the committee.

Conflict with Moynier

Differences of opinion soon developed between Moynier and Dunant regarding various aspects of the joint venture. Moynier had repeatedly called Dunant's proposal to place the wounded, nurses and auxiliary workers as well as hospitals under the protection of neutrality as impracticable and urged Dunant not to insist on this idea. Dunant, however, repeatedly disregarded Moynier's opinion on the matter during his extensive travels through Europe and his discussions with high-ranking politicians and the military. This exacerbated the conflict between the pragmatist Moynier and the idealist Dunant and led to Moynier's efforts to dispute Dunant's idealist claim to leadership.

During his travels through Europe, Dunant took part in the International Statistical Congress in Berlin from September 6 to 12, 1863. There he met the military doctor Johan Hendrik Christiaan Basting , who had already translated Dunant's book into Dutch . Dunant's assignment was to distribute a memorandum and an invitation from the International Committee to an international conference to the participants in the Congress. Together with Basting, and without consulting the members of the committee in Geneva, he added the idea of neutralizing the auxiliaries to the proposals contained in the memorandum. This unauthorized decision by Dunant on a central issue from Moynier's point of view deepened the conflict between the two. Basting then presented Dunant's ideas to the delegates present as a participant in the congress. Shortly after the congress, Dunant traveled to Dresden for an audience with King John of Saxony . To Dunant's request for support, the king replied with a sentence that Dunant quoted several times in letters to other high-ranking personalities:

"I will do what I can, because certainly a people who did not take part in this philanthropic work would be dismissed by the public opinion of Europe."

Conclusion of the Geneva Convention

In October 1863 the conference planned by the International Committee took place in Geneva. Representatives from 16 countries took part and discussed measures to improve aid for soldiers wounded in the field. At Moynier's instigation, Dunant himself was only the secretary of the conference. A year later, a diplomatic conference was held in August at the invitation of the Swiss Federal Council , during which the first Geneva Convention was signed on August 22, 1864 by twelve states . Here they also agreed on a uniform symbol to protect the wounded and the auxiliary personnel: the easily and widely recognizable Red Cross on a white background, the inversion of the Swiss flag.

Dunant had only been assigned the task of entertaining the guests for this conference. Nevertheless, he was the center of public attention for the next two years and received numerous honors and invitations. So he was in the spring of 1865 by Napoléon III. inducted into the French Legion of Honor la Légion d'honneur . In May of the same year he met personally with the French emperor in Algiers and received a non-binding promise from him that his operations in Algeria would be under the protection of the French government. In 1866 he was after the Prussian-Austrian war of Augusta , wife of the Prussian king, later to become German I. Kaiser Wilhelm invited to the victory celebrations in Berlin and received there with honor. Here he was able to experience how flags with the Red Cross next to the national flag were shown during the victory parade of the Prussian army .

1867–1895: Social decline and oblivion

Bankrupt

The year 1865 was marked by a series of catastrophic events in Algeria: After armed conflicts, a cholera epidemic, a locust plague , earthquakes, a drought and finally an exceptionally hard winter followed. As a result, Dunant's business situation deteriorated noticeably, to a not insignificant extent, however, also because he had neglected it because of his commitment to his ideas. In April 1867, the financing company Crédit Genevois, which was involved in his ventures, was dissolved . His membership on the board of directors of this company caused a scandal. He was forced to file for bankruptcy , which also seriously affected his family and friends because of their investments in his businesses. On August 17, 1868, he was convicted of fraudulent bankruptcy by the Geneva Commercial Court. Because of the social pressures at the time, this economic crash also led to demands to resign from the International Committee. On August 25, 1867 Dunant resigned as secretary of the committee, on September 8, he was completely expelled from the committee. Moynier, who had assumed the presidency of the committee in 1864, played a major role in this exclusion.

Dunant's mother died on February 2, 1868. Later that year he was also expelled from the YMCA. He had already left Geneva in March 1867 and was not to see his hometown again until his death after he was finally expelled from Geneva society following his conviction. Moynier likely used his relationships and influence several times in the ensuing period to prevent Dunant from receiving financial aid from friends and supporters in different countries. For example, due to Moynier's efforts, the Sciences Morales gold medal at the Paris World's Fair in 1867 was not awarded to Dunant as originally planned, but in equal parts to Moynier, Dufour and Dunant, so that the prize money was transferred to the International Committee. An offer by the French Emperor Napoléon III to take over half of Dunant's debts if his friends would pay for the other half also failed due to Moynier's influence.

After leaving Geneva, Dunant moved to Paris , where he lived in poor conditions. However, here too he tried to operate according to his ideas and ideas. In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/1871 he founded a general welfare society and shortly thereafter a general alliance for order and civilization . Its aims were to reduce the number of armed conflicts and the extent of violence and oppression by improving the moral and cultural standards of ordinary citizens in society through education. In addition, the alliance stood up for the protection of workers from unlimited exploitation by their employers, as well as against the atheistic and corrupting influence of the International Workers' Association, founded in London in 1864, from the perspective of the alliance . During his campaign for the goals of the General Alliance, Dunant called for, among other things, disarmament negotiations and the establishment of an International Court of Justice to mediate interstate conflicts in order to resolve them peacefully without the use of force.

Use in favor of prisoners of war

During the first congress of the General Alliance for Order and Civilization in Paris in 1872, an article by Dunant on the treatment of prisoners of war was read. He had already written this article in 1867 for the first Red Cross conference, at which this contribution was not discussed. After his suggestions were received with enthusiasm by those present, Dunant tried on a trip to England to win support for an international conference on the question of prisoners of war. He gave speeches to members of the English Social Science Association , an association comparable in its aims to the General Alliance, including on August 6, 1872 in London and on September 11 of the same year in Plymouth . During his performance in Plymouth, he collapsed from a faint attack.

Once again, his suggestions met with great approval and enthusiasm. Shortly after Napoléon III. had again pledged his support, he died on January 9, 1873 during a gallstone operation . In February 1874, Dunant was appointed International Secretary at the first congress of the Society for the Improvement of the Conditions of Prisoners of War , which was newly founded in Paris . The society planned to hold a diplomatic conference in May of the same year and asked Dunant to help with the preparations in Paris. Instead, on the initiative of the Russian Tsar Alexander II , a corresponding conference was held in Brussels in July and August 1874 . Due to discussions about a draft of the Russian government for an extension of the Geneva Convention, Dunant's proposals for the benefit of prisoners of war did not receive enough attention from the participants. The Brussels conference ultimately ended without any change to the Geneva Convention or any concrete decisions on the issue of prisoners of war. While Moynier, as President of the International Committee, was satisfied with the outcome because he feared the Geneva Convention would fail, Dunant was disappointed with the outcome of the conference.

live in poverty

In the following years he continued to campaign for the goals of the General Alliance. He wrote articles and gave lectures, including on the liberation struggle of the slaves in North America . Together with the Italian Max Gracia , he also suggested the establishment of a world library - an idea that was taken up by UNESCO about 100 years later . Another of his ideas, some of which were visionary, was the establishment of a state of Israel. With the commitment to his ideas, he neglected his personal affairs and continued to borrow. Because of his debts, he was shunned by the environment. He was also almost forgotten by the Red Cross movement, which spread through the founding of national societies in many countries during this time, even if the national Red Cross societies of Austria, Holland, Sweden, Prussia and Spain made him an honorary member. The time in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War and the domestic political disputes after the founding of the Third French Republic was another turning point in Dunant's life. He withdrew even further from the public and developed a pronounced shyness, which shaped his behavior until the end of his life.

In the following years Dunant led a lonely life in material misery, between 1874 and 1886 in Stuttgart , Rome , Corfu , Basel and Karlsruhe, among others . Few details about his life are known from this period. The financial support of friends as well as occasional activities with which acquaintances and patrons enabled him to earn a little saved him from a complete crash. These supporters included the American banker Charles Bowles , who had participated as a delegate at the diplomatic conference in 1864, Jean-Jacques Bourcart , a businessman from Alsace , and Max Gracia, who helped Dunant, among other things, in disputes with his creditors. Also Léonie Kastner-Boursault , the widow of the composer and music writer Jean-Georges Kastner , helped Dunant repeated in difficult situations. So she entrusted him with the task of marketing the pyrophone , a musical instrument invented by her son Frédéric Kastner . Even if Dunant was unsuccessful, this activity and a long trip to Italy together with Léonie Kastner-Boursault from 1875 to the beginning of the 1880s saved him from a life of complete poverty. In Stuttgart in 1877 he met the Tübingen student Rudolf Müller , with whom he later became a close friend.

Heathen

In 1881, accompanied by friends from Stuttgart, Dunant came to the small Swiss Biedermeier village of Heiden in the Appenzellerland for the first time . From 1887, while living in London, he received a small monthly financial support from his relatives. Since this enabled him to live a modest but safe lifestyle without poverty, in July of the same year he finally settled in Heiden in the Stähelin family's “Paradies” inn. After the family sold the guest house a few years later and moved to the nearby municipality of Trogen , he lived in the local hotel "Lindenbühl" from the end of 1890, although he did not feel at home. After just over a year he returned to Heiden and from April 30, 1892 lived in the local hospital, which was run by the doctor Hermann Altherr . Here he spent his retired old age, which in the following years was increasingly shaped by religious-mystical thoughts and prophetic ideas. The reasons for choosing Heiden include, in addition to the seclusion and good reputation as a health resort and recreation area, the view from the high altitude of Lake Constance , a view that reminded Dunant of his hometown and Lake Geneva and which he greatly appreciated during his walks .

Shortly after his arrival, he made friends with the young teacher Wilhelm Sonderegger and his wife Susanna. At Sonderegger's insistence, he also began to write down his memoirs. Sonderegger's wife suggested the establishment of a section of the Red Cross in Heiden, an idea that Dunant was extremely impressed with. In 1890 he became honorary president of the Heidener Red Cross Association founded on February 27 of the same year. With his friendship with Sonderegger and his wife, he had great hopes and expectations regarding the spread of his ideas, especially in the form of a new edition of his book. The friendship, however, later suffered greatly from unjustified accusations by Dunant that Sonderegger would make common cause with Moynier in Geneva. The early death of Sonderegger in 1904 at the age of only 42 weighed heavily on Dunant, despite the deep tensions between the two. The Sondereggers' admiration for Dunant, which they felt after Dunant's allegations, was later carried over to their children . In 1935, her son René published Dunant's letters from his father's estate.

1895–1901: rediscovery and recognition

Late remembering

In September 1895, Georg Baumberger , editor-in-chief of the newspaper Die Ostschweiz from St. Gallen , wrote an article about the founder of the Red Cross, with whom he happened to meet while walking in Heiden in August. This article, entitled Henri Dunant, the founder of the Red Cross , appeared in the German magazine Über Land und Meer , reprints were found throughout Europe within a few days. He was remembered and received sympathy and support from around the world. The general public was now aware of him again as the founder of the Red Cross movement, even though the International Committee in Geneva continued to avoid any contact with him. During this time, Dunant received the Binet-Fendt Prize from the Swiss Federal Council and from the then Pope Leo XIII. Recognition in the form of a picture with a personal dedication. Thanks to an annual pension from the Russian Tsar's widow and empress mother Maria Feodorovna and other monetary donations, Dunant's financial situation improved quickly.

In the history of the origins of the Red Cross and the Geneva Convention published in 1897 by Rudolf Müller, now a grammar school professor in Stuttgart, published by Greiner & Pfeiffer , Dunant's role as founder of the Red Cross was appropriately recognized for the first time since his retirement from the International Committee. The book also contained an abridged German-language new edition of A Memory of Solferino .

Publication of further publications

Dunant himself was in correspondence with the Austrian pacifist Bertha von Suttner at this time , after she had visited him personally in Heiden. At her suggestion, he wrote numerous articles and papers, including in the magazine she edited, Die Waffen Nieder! an essay entitled To the Press . In addition, he published excerpts from previously unpublished manuscripts under the titles Small Arsenal Against Militarism and Small Arsenal Against War .

Impressed by the work of Bertha von Suttner and Florence Nightingale , he came to believe that women would play a much greater role than men in the realization of lasting peace. In this context, he saw selfishness, militarism and brutality as typically male principles, while he attributed charity, empathy and the pursuit of non-violent conflict resolution to women. Based on this point of view, he also increasingly advocated equal rights for women. In 1897 he suggested the foundation of an international women's welfare association under the name “Green Cross”.

In February 1899, in the run-up to the first Hague Peace Conference, the essay The Proposal of Sr. Majesty of Emperor Nicholas II appeared in the German Revue . This was Dunant's last noteworthy attempt to publicly influence the peace efforts of the time.

Nobel Peace Prize

In 1901, Dunant received the first ever Nobel Peace Prize for founding the Red Cross and initiating the Geneva Convention . The Nobel Committee in Oslo informed him of the decision in the following telegram, which he received on December 10th of this year:

“To Henry Dunant, Heiden. The Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Parliament is honored to announce that it has awarded half of the 1901 Nobel Peace Prize to you, Henry Dunant, and half to Frédéric Passy. The committee sends its homage and sincere wishes. "

The Norwegian military doctor Hans Daae, to whom Rudolf Müller had sent a copy of his book, acted as Dunant's advocate on the Nobel Committee. Together with Dunant, the French pacifist Frédéric Passy was awarded the prize, the founder of the first peace league in Paris in 1867 and worked with Dunant in the Alliance for Order and Civilization . The congratulations that were officially sent to him on the occasion of the award ceremony by the International Committee meant a late rehabilitation after 34 years and were more important to him than all other awards, prizes, honors and expressions of sympathy in recognition of his services to the creation of the Red Cross. For the Red Cross movement, the award was an important recognition of its work and the importance of the Geneva Convention in an atmosphere of steadily increasing danger of war due to intensification of international tensions and increasing military armament.

Both Moynier and the International Committee were also nominated for the award. Although Dunant had been proposed by an extremely wide range of supporters - including three professors from Brussels and seven professors from Amsterdam, 92 members of the Swedish and 64 members of the Württemberg parliament, two ministers from the Norwegian government and the International Peace Bureau - he was a candidate not without controversy for the price. Opinions were divided about the effect of the Red Cross and the Geneva Convention on war: didn't they make war more attractive and therefore more probable, because they took away some of the suffering and horror associated with war? In a long letter to the Nobel Committee, Rudolf Müller had spoken out in favor of awarding the award to Dunant and proposed that the award should be shared between Frédéric Passy, who was originally intended to be the sole winner, and Dunant. Since awarding the award to Dunant was discussed in later years, he also referred to Dunant's advanced age and state of health.

The joint award of the prize to Passy and Dunant also took place against the background of some differences that existed at the time despite many similarities between the peace movement and the Red Cross movement. With the decision to split the first Nobel Peace Prize between Passy, a traditional pacifist and the most famous representative of the peace movement of the time, and the humanist Dunant, the Nobel Committee created two main categories of reasons for the award, to which many of the later winners can be assigned . On the one hand, there is the award to people and later also to organizations that dedicated themselves to peace work in the direct sense and thus corresponded to the part of the Nobel Testament that provides for the prize for those “who are most or best for… abolition or reduction of the standing armies as well as for the formation and dissemination of peace congresses (worked) ”. On the other hand, in the tradition of awarding Dunant, the award was subsequently also awarded for outstanding achievements in the humanitarian field. This follows an argument that ultimately also regards humanitarian work as peacemaking and appeals to a broad interpretation of that part of the Nobel Testament which determines the price for “who has worked most or best for the fraternization of peoples”.

Hans Daae managed to keep Dunant's share of the prize money of 104,000 Swiss francs in a Norwegian bank, thus protecting it from being accessed by its creditors. Dunant himself never touched the money in his life.

End of life

Last years of life

In addition to a few other honors that were bestowed on him in the following years, Dunant received an honorary doctorate from the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University together with Gustave Moynier in 1903 . However, there was no reconciliation with Moynier. Dunant lived in the hospital in Heiden until his death . He spent the last years of his life increasingly depressed. Until the end of his life he felt burdened by the fact that he was unable to pay his debts in full. He suffered from fear of persecution from his believers and his adversary Moynier. There were days when the hospital cook had to try the dishes for Dunant in front of his eyes.

In the last years of his life, Dunant despised all religious institutions and renounced Calvinism as well as any other form of organized religion, but continued to see himself connected to the Christian faith.

death

According to the information provided by the nurses who looked after him, the last conscious act in Dunant's life was that he sent a copy of Rudolf Müller's book together with a personal dedication to Queen Elena of Italy . He died in the evening hours of October 30, 1910 around 10 p.m., surviving Moynier by about two months. His last words were addressed to Hermann Altherr: "Ah, que ça devient noir!" ("How dark it gets around me!")

“I wish to be buried like a dog, without a single one of your ceremonies that I do not recognize. I confidently count on your kindness to watch over my last earthly wish. I'm counting on your friendship to make it happen. I am a disciple of Christ like in the first century, and nothing else. "

According to these words, formulated in a letter to Wilhelm Sonderegger in 1890, for which his will is incorrectly cited as the source in many depictions of his life, he was buried three days later, inconspicuously and without a memorial service, in the Sihlfeld cemetery in the city of Zurich . The few mourners present included Hermann Altherr and Rudolf Müller, some delegates from Red Cross associations from Switzerland and Germany, as well as his nephews who had traveled from Geneva.

testament

On May 2 and July 27, 1910, Dunant wrote his will . With this, he donated the modest fortune that he had at the time of his death due to the Nobel Prize money and numerous donations, a free bed in the hospital in Heiden for the sick among the poor citizens of the place. In addition, he thanked some of his closest friends, including Rudolf Müller, Hermann Altherr and his wife, as well as employees of the Heiden hospital, with small sums of money. He donated half of the rest to charitable organizations in Norway and half in Switzerland and gave his executor the power to decide on the choice of recipients.

He left all books, notes, letters and other documents in his possession as well as his awards to his nephew Maurice Dunant, who lived in Geneva. His correspondence with Rudolf Müller, which was informative for research and, in over 500 letters, provided information about Dunant's life from 1877 onwards, was published in 1975.

Reception and aftermath

Life's work

The fact that almost all of Henry Dunant's ideas were realized over time and are largely still relevant today shows that many of his visions were ahead of his time. In addition to the establishment of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and the expansion of the activities of the International Committee to include prisoners of war, this also applies, among other things, to the World Federation of Christian Young Men , for the establishment of the State of Israel , for the creation of a care organization the cultural heritage of mankind in the form of UNESCO and for its commitment to the liberation of slaves in North America and for the legal equality of women . However, when assessing his services to founding the Red Cross, the role of his adversary Gustave Moynier must also be taken into account. Through his book, his charismatic demeanor and his activities in the run-up to the Geneva Conference of 1863, Dunant undoubtedly played a decisive role in bringing about the International Committee and the Geneva Convention. In the history of the origins of the Red Cross he was thus the idealist, without whose ideas the historical development after the Battle of Solferino would most likely have taken a different course. It was only his accidental presence at the site of a war like many others of the time, the processing of his experiences in a book and the suggestions he developed in it that gave the town of Solferino and the year 1859 their current place in history. On the other hand, this success would hardly have been possible without the pragmatic work of Moynier, who was also largely responsible for the further development of the committee after its establishment and the expansion of the Red Cross movement and its activities.

How much the combination of the work of both men had contributed to the success that the Red Cross and the Geneva Convention represent from a historical point of view was shown by the fate of Dunant's proposals on the question of prisoners of war . Around ten years after the founding of the International Committee and the adoption of the Geneva Convention, the development of its commitment to the prisoners of war initially showed some parallels to the events of 1863 and 1864. Even if the ultimate failure had several reasons, such as the competition from Alexander II and his Brussels Conference of 1874 , a renewed collaboration between Dunant and Moynier might have been more successful. A legal solution to the treatment of prisoners of war was only partially implemented 25 years later in the Hague Land Warfare Regulations of 1899 and 1907 and in full only decades after the deaths of Dunant and Moynier by the Geneva Convention on POWs of 1929 and 1949, respectively. The point of view that Dunant and Moynier equally attributed their own share in the emergence of the Red Cross movement and sees both Dunant and Moynier's work as a prerequisite for success is also questioned by some authors. According to their opinion, both were so different in terms of their ideals and character traits that substantial cooperation for a common goal with mutually complementary activities was practically impossible. According to this view, a corresponding representation of the history of the Red Cross is based on attempts to gloss over Moynier's role.

Awards and recognition

Henry Dunant's achievements have been and are honored in many ways up to the present day. Outstanding from the large number of honors that have been bestowed on him, particularly in the last 15 years of his life, is the Nobel Peace Prize. His birthday, May 8th, is celebrated annually by the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement in his honor as World Red Cross and Red Crescent Day . On October 29th, the day before his death, the Evangelical Church in Germany will remember him with a memorial day in the Evangelical Name Calendar . The Henry Dunant Medal , awarded every two years by the Standing Commission of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, is the movement's highest honor.

The Dunant monument on Dunantplatz in Heiden was created by Charlotte Germann-Jahn . It was inaugurated on October 28, 1962, the Sunday before the 52nd anniversary of Henry Dunant's death. To mark the centenary of the founding of the International Committee in 1963, a monument was erected in his honor in Dunant's hometown of Geneva. The inauguration of the monument created by Jakob Probst in the Parc des Bastions took place on Dunant's birthday on May 8th.

In 1969 the Henry Dunant Museum Heiden opened in the former hospital where Dunant had last lived. In October 1988, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum was opened in Geneva , in which two rooms are dedicated to the Battle of Solferino and the founding of the Red Cross.

In Geneva and several cities in other countries streets, squares, schools and other institutions are named after Dunant. The asteroid discovered in 1973 (1962) Dunant was named after him; also in 2014 the Dunantspitze , a peak in the summit ridge of Monte Rosa , which is only two meters lower than its main summit.

Literary representations

In 1938 Martin Gumpert's book became Dunant. The Red Cross novel published, a literary adaptation of Dunant's biography. The book J. Henry Dunant , published in several editions between 1962 and 1985, is one of the most important documentary works in German . Founder of the Red Cross, originator of the Geneva Convention by Willy Heudtlass and Walter Gruber . At the beginning of the 1960s, among other things, the author Willy Heudtlass was able to evaluate two previously unknown letter archives that were in the possession of the descendants of Rudolf Müller and Hans Daaes.

In Eveline Hasler's biographical novel The Time Traveler. The Visions of Henry Dunant (1994) depicts Dunant's life from the narrative perspective of an anonymous observer, alternating memories and current descriptions of the last years of his life.

Movie

In 1948, a 96-minute film by director Christian-Jaque with the title D'homme à hommes was released as a Franco-Swiss co-production . Performer Dunants was the French actor Jean-Louis Barrault . A German-language version with the title Von Mensch zu Mensch was shown in 1964 in the cinemas of the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

1966 followed the documentary Honored by Everyone: Henry Dunant , directed by Gaudenz Meili . In 1998 the Henry Dunant Museum Heiden produced an approximately 30-minute documentary film entitled Henry Dunant (1828–1910) .

The first television film about Dunant premiered in 2006: Henry Dunant - Red on the Cross (French original title Henry Dunant: Du Rouge Sur La Croix ) with Thomas Jouannet in the role of Henry Dunant. The feature film with a running time of around 100 minutes was directed by Dominique Othenin-Girard in cooperation between broadcasters and producers from Austria, Switzerland, France, Algeria and Greece.

theatre

Dunant's life story was implemented as a theater play by Dieter Forte under the title Jean Henry Dunant or The Introduction of Civilization , first performed on March 30, 1978 in the Darmstadt State Theater .

Works (selection)

- Notice on the Régence de Tunis. Geneva 1858.

- L'Empire de Charlemagne rétabli ou Le Saint-Empire romain reconstitué par sa Majesté L'Empereur Napoléon III. Geneva 1859.

- Mémorandum au sujet de la société financière et industrial des Moulins de Mons-Djémila en Algérie. Paris, undated (ca.1859)

- Un Souvenir de Solférino . Geneva 1862

- L'Esclavage chez les musulmans et aux États-Unis d'Amérique. Geneva 1863.

- La charité sur les champs de bataille. Geneva 1864.

- The prisonniers de guerre. Paris 1867.

- Bibliothèque internationale universal. Paris 1867.

- To the press. In: Lower your arms! Vienna 1896, No. 9, pp. 327–331.

- Small arsenal against militarism. In: Lower your arms! Vienna 1897, No. 5, pp. 161–166; No. 6, pp. 208-210; No. 8-9, pp. 310-314.

- Small arsenal against the war. In: Lower your arms! Vienna 1897, No. 10, pp. 366-370.

literature

- Willy Heudtlass, Walter Gruber: J. Henry Dunant. Founder of the Red Cross, originator of the Geneva Convention. A biography in documents and pictures. Fourth edition. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-17-008670-7 .

- Franco Giampiccoli, Elena Ascheri-Dechering (transl.): Henry Dunant: The founder of the Red Cross. Sowing, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2009, ISBN 978-3-7615-5722-8 .

- Pierre Boissier : History of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Volume I: From Solferino to Tsushima. Henry Dunant Institute, Geneva 1985, ISBN 2-88044-012-2 .

- Caroline Moorehead : Dunant's Dream: War, Switzerland and the History of the Red Cross. HarperCollins, London 1999, ISBN 0-00-638883-3 .

- Angela Bennett: The Geneva Convention: The Hidden Origins of the Red Cross. Sutton Publishing, Gloucestershire 2005, ISBN 0-7509-4147-2 .

- Hans Amann: Henri Dunant: The Appenzellerland as his second home. (= The Land of Appenzell. Issue 23). Appenzeller Verlag, Herisau 2008, ISBN 978-3-85882-118-8 .

- André Durand : The First Nobel Prize (1901): Henry Dunant, Gustave Moynier and the International Committee of the Red Cross as Candidates. In: International Review of the Red Cross. 842/2001. ICRC, pp. 275-285, ISSN 1560-7755 .

- Raimonda Ottaviani, Duccio Vanni, M. Grazia Baccolo, Elizabeth Guerin, Paolo Vanni: Rewriting the Biography of Henry Dunant, the Founder of the International Red Cross. In: Vesalius - Acta Internationalia Historiae Medicinae. 11 (1 )/2005. International Society for the History of Medicine, pp. 21-25.

Further publications

- Lisette Bors: Who is Henry Dunant? Two children discover the story of Henry Dunant and the Red Cross. Children's and young people's book. Zeit -fragen , Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-909234-08-0 .

- Felix Christ: Henry Dunant. Life and Faith of the Red Cross Founder. Friedrich Wittig Verlag, Hamburg 1983, ISBN 3-85740-092-7 .

- Marc Descombes: Henry Dunant: Financier - Phantast - Founder of the Red Cross. Schweizer Verlagshaus, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-7263-6554-0 .

- Emanuel Dejung: The second turning point in the life of Henry Dunant 1892–1897: His correspondence with the Winterthur section of the Red Cross. (= Neujahrsblatt der Stadtbibliothek Winterthur. Volume 294). Winterthur 1963.

- Elke Endraß: The benefactor. Why Henry Dunant founded the Red Cross. Wichern Verlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-88981-288-9 .

- Eveline Hasler : The time traveler. Henry Dunant's visions. Verlag Nagel & Kimche, Zurich 1994, ISBN 3-312-00199-4 .

- Martin Gumpert : Dunant. The Red Cross novel. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt 1987, ISBN 3-596-25261-X .

- Werner Legère : The reputation of Castiglione. Henri Dunant, a life in the service of humanity. Eighth edition. Evangelical Publishing House, Berlin 1978.

- Gabriel Mützenberg: Henry Dunant, le prédestiné. You nouveau sur la famille, la jeunesse, la destinée spirituelle du fondateur de la Croix-Rouge. Robert-Estienne, Genève-Acacias 1984.

- Daniel Regli: The Henry Dunant Apocalypse. The historical picture of the Red Cross founder in the tradition of eschatological expectation. Peter Lang, Bern 1984, ISBN 3-906752-72-0 .

- Dieter and Gisela Riesenberger: Red Cross and White Flag: Henry Dunant 1828–1910. The person behind his work. Donat Verlag , Bremen 2010, ISBN 978-3-938275-83-2 .

- Yvonne Steiner: Henry Dunant. Biography. Appenzeller Verlag, Herisau 2010, ISBN 978-3-85882-537-7 .

- Philipp Osten : The Voice of Solferino - Telegraphy and Military Reporting. A press review. In: Wolfgang U. Eckart , Philipp Osten: The Red Cross and the invention of humanity in war. (= Modern history of medicine and science. Volume 20). Centaurus Verlag, Freiburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-86226-045-4 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Henry Dunant in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Henry Dunant in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Publications by and about Henry Dunant in the Helveticat catalog of the Swiss National Library

- Jean de Senarclens: Dunant, Henry. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Société Henry Dunant Website of the Swiss Henry Dunant Society (French)

- Henry Dunant on ICRC (English)

- Henry Dunant Museum Website of the Dunant Museum in Heiden AR , Switzerland

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1901 award ceremony for Henry Dunant (English)

Notes and individual references

- ↑ Dunant was called "Jean-Henri" when he was baptized . Later he himself used different spellings for his first name several times in his correspondence, including "Jean Henry", "Henri", and preferred "Henry". In his time, the spelling of proper names was handled more flexibly than it is today, so that in particular the name "Henry" can be found in many publications instead of his baptismal name and is also used, for example, by the Société Henry Dunant and the Henry Dunant Museum in Heiden. An explanation for the self-chosen change of his first name can be found in a letter to Rudolf Müller a few years before his death: “It was towards the end of 1854 when I came back from a Mediterranean trip lasting several months. For the first time I saw the new address book for the city of Geneva and discovered the following name in it: Henri Dunant, shoe embroiderer . ”To avoid confusion, he used the English spelling“ Henry ”almost exclusively from around 1857 and only in his will and a few others legal documents his baptismal name.

- ^ Wolfgang U. Eckart : Illustrated history of medicine , Springer Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 1. + 2. Edition 2011, here: Tutti Fratelli - Solferino and the> invention <of humanity in war. Pp. 244-249. Illustrated History of Medicine 2011

- ^ Hauke Brankamp, Anne Dieter, Manuela Ludewig: The founder of the Red Cross Henry Dunant on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his death. University of Potsdam, Potsdam 2010, p. 2 ( PDF , approx. 1.13 MB).

- ^ Marc van Wijnkoop Lüthi: Christian Association of Young Men (YMCA). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Hans Hauzenberger: Swiss Evangelical Alliance (SEA). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Swissinfo: Quand des Suisses créaient une colonie privée en Algérie

- ↑ The description, which can sometimes be found, that he did not arrive in Solferino on June 24, but only three days later on June 27, 1859, contradicts the description in his book. For example, he describes how, on the morning of the Sunday after the battle, he persuaded women to give aid. Since June 24th, 1859 was a Friday, it is June 26th. He also describes how he went on a trip with his carriage on the afternoon of June 27th to recover from the exertions of the previous days.

- ^ Friedrich Samuel Rothenberg: Dunant, Henri. In: Evangelisches Gemeindelexikon. R. Brockhaus, Wuppertal 1986, ISBN 3-417-24082-4 , p. 131.

- ↑ Although Louis Appia and Henry Dunant stayed for a short time in the war zone in northern Italy for a short time in 1859 and devoted themselves to helping the wounded, there is no evidence in their records or other memories that they met each other at that time or otherwise had knowledge of each other's work. Even if such an encounter cannot be completely ruled out, it seems unlikely in view of this.

- ↑ Despite the intense and detailed description of the battle in his book, Dunant was, unlike in some accounts of his life, not a direct eyewitness to the fighting. On June 24, 1859, he did not arrive in Solferino until the evening, after the conflict had ended. The description of the fighting in his book therefore does not contain any statements from the first-person perspective, unlike his remarks on the conditions after the battle.

- ↑ Dunant had written the letter to Wilhelm Sonderegger in autumn 1890 in a state of severe depression. See Hans Amann: Henri Dunant: The Appenzellerland as his second home. Herisau 2008, p. 22.

- ↑ a b For the full text of the will, see Willy Heudtlass: J. Henry Dunant. Founder of the Red Cross, originator of the Geneva Convention. Stuttgart 1985, pp. 247-250.

- ^ Raimonda Ottaviani, Duccio Vanni, M. Grazia Baccolo, Elizabeth Guerin, Paolo Vanni: Rewriting the Biography of Henry Dunant, the Founder of the International Red Cross. In: Vesalius - Acta Internationalia Historiae Medicinae. 11 (1 )/2005. International Society for the History of Medicine, pp. 21-25.

- ^ Henry Dunant in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- ↑ Half a century Dunant memorial tagblatt.ch, October 25, 2012.

- ^ On inaugure à Genève un monument à la mémoire de Henry Dunant , in: International Review of the Red Cross, edition of June 1, 1963, pp. 296-301.

- ↑ Henry Dunant - Red on the Cross Data on the film on imdb.com

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dunant, Henry |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Dunant, Jean Henri (maiden name); Dunant, Henri |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Initiator of the Red Cross movement and co-founder of the International Committee of the Red Cross |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 8, 1828 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Geneva , Switzerland |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 30, 1910 |

| Place of death | Heiden , Switzerland |