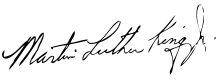

Martin Luther King

Martin Luther King Jr. (born January 15, 1929 in Atlanta , Georgia as Michael King Jr; † April 4, 1968 in Memphis , Tennessee ) was an American Baptist pastor and civil rights activist .

He is considered one of the most outstanding representatives in the non-violent struggle against oppression and social injustice and was the best-known spokesman for the Civil Rights Movement between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s , the American civil rights movement of African-Americans . He propagated civil disobedience as a means against the political practice of racial segregation in the southern states of the USA on religious grounds and took part in corresponding actions.

Essentially through King's commitment and effectiveness, the Civil Rights Movement has become a mass movement, which has finally achieved that racial segregation was legally abolished and unrestricted suffrage for the black population of the US southern states was introduced. Because of his commitment to social justice , he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 . On April 4, 1968, King was shot dead in an assassination attempt in Memphis .

Life

Family and childhood

King was born the son of Alberta teacher Christine Williams King (1904-1974) and her husband Martin Luther King (1897-1984, originally Michael King), the 2nd preacher of the Baptist Ebenezer Congregation Atlanta. Before he started working as a pastor, his father was, among other things, a mechanic in a car repair shop and a fire fighter at a railway company. King Senior had graduated from evening school and was chairman of the Atlanta National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) before King Junior was born .

King Jr.'s maternal grandfather, Adam McNeil Williams (* 1863), a son of slaves , joined the Ebenezer community in 1894. All subsequent generations also belonged to this parish. The paternal grandfather, James King, had worked on cotton plantations near Stockbridge , about 12 miles from Atlanta. For the father and later for the son, the name Martin Luther was an expression of deep religious sentiment. Originally King's father was called Michael King and he himself was called Michael King Jr. The father changed both names after a trip to Europe in 1934, which also took him to Germany in connection with the Baptist World Congress in Berlin, in honor of Martin Luther , for whom he felt great admiration. King Junior lived with his parents at 501 Auburn Avenue until 1941, a street almost exclusively inhabited by wealthy blacks.

Like all blacks , he was discriminated against by the racial segregation in the southern United States at the time. This separated all areas of daily life in black and white: schools, churches, public buildings, buses and trains, even toilets and sinks. King saw such segregation as a great injustice at an early age , and this attitude was shaped primarily by his father's upbringing. When he was 14, he drove from Atlanta to Dublin , Georgia , to take part in a speaker competition, which he won. Even then, he publicly campaigned for desegregation and also for the strengthening of the USA as a nation. Clayborne Carson quotes King in his "Autobiography" Kings as saying:

“We cannot have an enlightened democracy if a large group lives in ignorance. We cannot be a healthy nation if one tenth of the population is malnourished, sick, and carries germs that make no difference between skin colors, and does not obey Jim Crow laws . "

On June 18, 1953, King and Coretta married Scott Williams . The wedding took place at her parents' home in Marion , Alabama; the wedding was performed by King's father. The couple had four children:

- Yolanda Denise (born November 17, 1955 in Montgomery , Alabama - † May 15, 2007 in Santa Monica , California)

- Martin Luther III (born October 23, 1957 in Montgomery, Alabama)

- Dexter Scott (born January 30, 1961 in Atlanta, Georgia)

- Bernice Albertine (born March 28, 1963 in Atlanta, Georgia)

All four are committed or committed, like their father, to civil rights; their published texts and speeches differ thematically. King's widow, Coretta Scott King, died on January 30, 2006 at the age of 78 in Rosarito Beach, Mexico .

Education and Influences

King had his first negative racial segregation experience when he started primary school. His closest friend in preschool was a white boy from the immediate neighborhood. Then the two had to go to different schools, and his friend's parents told King that he could no longer play with their son because he was black. King went to Younge Street Elementary School with his sister Christine, which had only black students. Learning was relatively easy for him. In the sixth grade he switched to the "David T. Howard Colored Elementary School". At the age of 13 he finally attended "Booker T. Washington High School", where he skipped the ninth and twelfth grades.

On September 20, 1944, King began his studies at Morehouse College , the only college for blacks in the south; despite his age of not yet 16 years, it accepted him as an exception. With a major in sociology, Walter P. Chivers introduced him to the problem of racial segregation ; from George D. Kelsey, head of the School of Religion, he heard about Mahatma Gandhi's nonviolent resistance. Benjamin Mays , then president of the school and a civil rights activist, was an important mentor to King. In other ways too, King describes the atmosphere at the college as constructive and largely free of racism and intolerance towards blacks. In 1948 he graduated from college with a Bachelor of Arts degree in sociology .

While studying, King became his father's assistant minister at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta at the age of 17. Despite his deep faith, he didn't want to become a preacher at the time. In college, he finally discovered talking for himself and soon took top places in student competitions in political speech. Finally convinced of father and professors, he studied at the "Crozer Theological Seminary" in Chester , Pennsylvania, theology .

He read Plato , John Locke , Jean-Jacques Rousseau , Aristotle , Henry David Thoreau and Walter Rauschenbusch . Books by the latter prompted King to redefine the role and responsibility of a preacher for himself:

“For me, preaching is a dual process. On the one hand, I have to try to change the soul of every individual so that society can change. On the other hand, I have to try to change society so that every single soul can change. That's why I have to worry about unemployment, slums and economic insecurity. "

In addition, he dealt intensively with various theories of social forms and read, for example, Karl Marx , by whom he was influenced, although he largely rejected him:

“Reading Marx convinced me that the truth cannot be found in either Marxism or traditional capitalism. Both represent a partial truth. Historically, capitalism overlooked the truth of corporate corporations and Marxism failed to recognize the truth of individual corporations. Nineteenth century capitalism ignored the social aspects of life, and Marxism overlooked and overlooked the fact that life is individual and personal. The Kingdom of God is neither the thesis of individual undertakings nor the antithesis of collective undertakings, but represents a synthesis that unites the truths of both. "

He was also strongly influenced by Mahatma Gandhi, whose successful, charitable struggle with the means of nonviolence deeply impressed him. King once said of Gandhi:

"It was through Gandhi's focus on love and non-violence that I discovered the method of social reform I was looking for."

Later he read texts critical of pacifism by Reinhold Niebuhr . These could not dissuade him from nonviolent resistance, but changed his view of the world:

“While I still believed in the good in people, Niebuhr also showed me their potential for evil. He also helped me to see the complexity with which man is involved in the dazzling existence of collective evil. "

In May 1951 he finished his studies with a Bachelor of Divinity in theology. He had several offers for the time after his studies. King did not choose the easy way, but chose a pastor's position in the south of the country. In 1954 he was pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama .

At that time he was writing his doctoral thesis at Boston University in Massachusetts with the title A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman , for which he was awarded the title Doctor of Philosophy in 1955. In 1991 it became known that parts of the work contained plagiarism. While he was writing his dissertation, he continued to study Gandhi's theses on nonviolence.

First successes - Montgomery

On December 1, 1955, the black civil rights activist Rosa Parks in Montgomery refused to vacate her seat on a public bus for a white man. She was arrested and given a fine. This led to a great solidarity movement within the black population. Just under a third of Montgomery's population were black; most of them worked as farm laborers and domestic servants.

For December 5th, the day of the trial against Rosa Parks, the Women's Political Council organized a one-day boycott of public buses. It called on the black population to carpool, use taxis or walk. Almost 100 percent of blacks did this; it became clear that the black population was united behind the protest.

The boycott was intended to show how much white entrepreneurs were economically dependent on the black population and how little rights they were given in return. The boycott lasted about 385 days. The then newcomer 26-year-old King was appointed head of the Montgomery Improvement Association, which was established to coordinate the boycott. He was advised by civil rights activist and openly homosexual Bayard Rustin in the post-Gandhi nonviolent resistance. The boycott also caused a stir abroad. In addition to verbal approval, there was also financial support for the city's black residents, for example from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). On January 31, 1956, the parsonage where King lived with his family was partially destroyed by a bomb attack; nobody was harmed.

The nonviolent resistance eventually led to success. On 13 November 1956, told Supreme Court that racial segregation in public transport in the city Montgomery unconstitutional, saying a ban against. The Montgomery bus boycott was seen as a great victory, and King's contributions to it led him to be elected President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), newly formed on January 10, 1957 . Another bomb attack was carried out on the pastorate on January 27th. A few days later, the police arrested seven white men, two of whom confessed to the attack. Nevertheless, they were released again. King traveled thousands of miles across the southern United States over the next several years, advocating non-violent and unrelenting advocacy for civil rights. In 1957, King gave 208 speeches and wrote his first book - “Steps to Freedom: The Montgomery Story” (Original: Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story ). The successful boycott increased the importance of the nonviolent civil rights movement enormously; In the years that followed, more and more whites joined her.

In 1960, King left his pastor in Montgomery to share a pastorate with his father at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. This gave him more time to participate in the civil rights movement. On October 19, 1960, King was arrested after a sit-in . He refused to leave bail; therefore he was kept in prison. When authorities in neighboring DeKalb County learned he was in jail, they requested his extradition. For failing to re-register his driver's license when he moved from Montgomery to Atlanta, he had been fined and given a year probation. King assumed the probation only related to the driver's license; the authorities in DeKalb said he shouldn't come into conflict with the law for a year.

A judge sentenced Martin Luther King to four months of forced labor on October 25, 1960. King was then transferred to a maximum security prison in Reidsville, Georgia . He got bad food there and caught a bad cold. On October 28, his fate turned: John F. Kennedy , then Democratic presidential candidate in the November 1960 presidential election , called King's wife Coretta King and offered to help. A short time later, King was released on $ 2,000 bail. In total, King was arrested 29 times during his career.

1960 election

On November 8, 1960, Kennedy won the presidential election ahead of Richard Nixon (303 to 219 electors). King's wife later wrote in her autobiography that the votes of most black voters helped Kennedy win the election.

First defeats - Albany

On December 15, 1961, King flew to Albany , Georgia. The so-called Freedom Rides had recently started there : non-violent and little organized protest of small groups against the public racial segregation. One day after his arrival, King and 600 people illegally demonstrated in Albany. The group was surrounded by the police and arrested without the use of force. Thereafter, until 1962, there were repeated unauthorized protests and unrest in Albany, which were not very successful. King's great influence contributed to the fact that non-violence was initially seen as the only realistic possibility for change. From around 1963 We Shall Overcome , sung by Joan Baez , who worked politically with King, became the anthem of the civil rights movement.

Birmingham: "The metropolis of racial segregation" (King)

King looked for reasons for the unsuccessful actions in Albany and found them mainly in the lack of preparation and organization. Together with his colleagues - including his "right hand man", Ralph Abernathy - he was looking for new goals and decided on Birmingham (Alabama) . King's group drew up a concrete plan to push those in power to legally guaranteed equality between blacks and whites. First, the local Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights around Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth ("You have to be ready to die before you can really start living") merged with the organization around King. All forces should be directed towards one goal; the activists only blocked the lunch counters (small, white-only snack bars in department stores) with peaceful seated protests. A boycott of department stores run by white businessmen was also planned. 250 volunteers were trained in methods of nonviolent resistance. Musician Harry Belafonte helped by raising money for these protests from wealthy blacks.

On April 3, 1963, 30 volunteers started sit-in strikes . These took place day after day; In the evening there were meetings of the protesters with King in various churches. He made speeches there and tried to motivate the demonstrators. The protest became more and more popular; there were also some dissenting votes among blacks. It has been argued that the protests came at the wrong time or that they disturb the peace. On April 10, Circuit Judge W. A. Jenkins issued a general injunction against “parading, demonstrating, boycotting, trespassing and picketing” (parading, demonstrating, boycotting, unauthorized entry into property and setting up pickets). Campaign leaders said they would not obey this order. On April 12th, King, Ralph Abernathy , Fred Shuttlesworth and other activists were rudely arrested in front of thousands of demonstrators.

King was treated unusually harshly in Birmingham prison. He was forbidden to make contact with the outside world . Someone smuggled an April 12 newspaper into prison that contained an open letter entitled " A Call for Unity " (written by eight white Alabama ministers). The letter criticized King and his methods. King wrote a response to this call ( Why We Can't Wait ; known in German as the Letter from Birmingham Jail ). The April 16 letter boosted King's popularity again; King was released from prison after eight days.

King had the idea of including children and young people in the protest. On May 2, 1963, 959 children were arrested who demonstrated for equality and for integrated schools, where black and white should be taught together. A day later, the police used massive violence against the demonstrators. On May 4th, pictures were published nationwide showing the brutality of the police action. This brutality did not detract from the protests; State violence also continued. President Kennedy sent an advisor from the Justice Department to Birmingham, who was supposed to secretly initiate negotiations between the leadership of the demonstration on the one hand and influential white businessmen and the Senior Citizens Committee in parallel to the protests . Due to the pressure of the ongoing demonstrations, an agreement was reached on May 10th. Agreements were made to lift the racial barriers in all restaurants in the city, to remove the ban on blacks from becoming employees or sales representatives, to set up a mixed commission to develop new foundations for the relationship between blacks and whites, and to release the 2,500 blacks arrested during the May Days clash.

A day later, two bombs detonated in front of the motel where King and his younger brother Alfred Daniel lived; nobody was injured. The perpetrators probably came from the environment of the Ku Klux Klan ; they were never caught. There was also further unrest in which 50 people were injured. Kennedy sent 3,000 federal soldiers to pacify the crisis area, after which the situation eased. Murders of black and white civil rights activists in the southern United States repeatedly shook the public. The perpetrators always came from circles of militant white racists . Mention should be made of the murder of the black civil rights activist Medgar Evers in June 1963, a bomb attack on the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham in September 1963 in which four girls were killed, and the kidnapping and murder of three civil rights activists in Mississippi in June 1964. In the first case, the killer was a member of the White Citizens' Council , which openly defended racial segregation. In the other murders, the perpetrators belonged to the secret society Ku Klux Klan, in which police officers from the southern states were also involved.

March on Washington, Nobel Peace Prize

initial situation

During this time, many black people developed a strong sense of self. They confessed to their African descent and the culture of their continent of origin and increasingly defended themselves against insults as stupid " Jim Crow " and against other everyday humiliations. But this self-image also led to black nationalism in a minority, which was in contrast to King's idea of a peaceful coexistence of all Americans.

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

President Kennedy put in response to the ongoing demonstrations on June 19, 1963 the US Congress a bill ( Civil Rights Act ) for the extensive nationwide equality before. In the summer of 1963, 841 demonstrations were held in 196 cities within four months. On July 22nd, leaders of several black movements met the President at the White House , where Kennedy tried to convince King and the others that the proposed March on Washington for Work and Freedom in Washington, DC came at an inopportune time given the bill . But King wanted the demonstration to go as planned. The march was supposed to once again, this time in the state capital, sensitize the masses to problems of blacks and induce conservative politicians to give in.

More than 250,000 people took part in the peaceful demonstration on August 28, 1963, including 60,000 whites and, in addition to King, six other black leaders, also to support President Kennedy's civil rights legislation. Here King gave his most famous speech, which went down in history under the title I Have a Dream . After the March on Washington began FBI boss Hoover , King and other civil rights activists to let spy intensively.

July 1964: Proclamation of the desegregation law

The Kennedy assassination November 22, 1963 shocked the civil rights movement. But his successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson , also supported the demand for equal rights for African Americans. On July 2, 1964, in the presence of King, the new president signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , which desegregated the race, in a ceremony . Before the resolution was passed, 19 senators tried to postpone the decision by holding speeches over 57 days and yet still prevent a majority for the law. After his announcement, the governor of Alabama refused George Wallace and the governor of Mississippi , Paul Johnson to recognize it.

September 1964: World Baptist Congress in Amsterdam, trip to Germany

In September 1964, King attended the Amsterdam Baptist World Congress . On September 13th he preached in front of 20,000 people in the West Berlin Waldbühne and in two East Berlin churches, the Marienkirche on Alexanderplatz and the Sophienkirche .

King had traveled unannounced from West to East Berlin, even against the will of the American authorities who had confiscated his ID . The credit card presented by King instead was accepted as identification at the Checkpoint Charlie border crossing ; The trigger was that 14 hours earlier, GDR border guards had shot at and seriously injured jockey Michael Meyer, who was then known in the GDR and who was fleeing over the Berlin Wall : an American sergeant saved his life by pulling the seriously injured man from the death strip to the West . In East Berlin's crowded churches in front of thousands of people, King criticized "dividing walls of hostility" and brought them greetings from all over the world:

“Here are God's children on both sides of the wall. And no man-made limit can erase that fact. Regardless of the barrier of race, creed, ideology or nationality, there is an inseparable determination: There is a common humanity that makes us sensitive to the suffering of one another. With this belief we can carve a stone of hope out of the mountain of despair. In this faith we will work with one another, pray with one another, fight with one another, suffer with one another, stand up together for freedom, knowing that one day we will be free. ... Hallelujah! "

December 1964: Nobel Peace Prize

On December 11, 1964, King received the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo . He donated the US $ 54,000 prize money to a fund of his movement. The US news magazine Time named the civil rights activist " Man of the Year 1963 ".

Selma

In 1965 in the small town of Selma near Montgomery, King attempted demonstrations to get blacks to be included in the electoral roll without reservation. Back then, a black man had to answer questions about American history or the constitution correctly before he could exercise his right to vote.

First, King organized several marches to the Selma courthouse. But day after day the police, under Sheriff Jim Clark, dispersed the demonstrators, many of them were arrested. After a police officer shot and killed the black woodcutter Jimmy Jackson, King decided to organize a large demonstration in nearby Montgomery , capital of Alabama. But in two attempts, the demonstrators were dispersed by the police behind Selma's city limits. Only a third march reached - under the protection of soldiers of the US Army and the National Guard , which President Johnson had sent - in March 1965 his goal. Johnson had supported King's call for a new law to strengthen the voting rights of blacks and other minorities, but was initially skeptical about the possibilities of getting it implemented in Congress.

After the March of Selma, the president changed his assessment and in March 1965 spoke out in favor of a new electoral law. That summer, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act , which Johnson signed on August 6, 1965 in the presence of King and other civil rights representatives. The law ruled discriminatory election tests inadmissible and provides for election observers to be sent to regions where discrimination is particularly likely.

Violent uprisings across the country - nonviolent attempts in Chicago

As racism and social injustice persisted in the United States despite all laws and court rulings, a radical wing formed within the civil rights movement. He was mainly represented by the Black Muslims with their charismatic leader Malcolm X and the Black Panther Party . These two violent groups were mainly represented in the big cities of the north and California, where the non-violent ideas of King had a difficult time. The reasons given are often the larger number of blacks in the ghettos of the big cities and the complete lack of prospects. Because while blacks in the south often hoped to flee to the "just" north, there were no such hopes for blacks in the north.

On August 11, 1965 , an unplanned, violent uprising by blacks broke out in Watts, a residential district in the south of Los Angeles , California, in which businesses of whites in particular were damaged. Other cities followed, albeit with less dramatic excesses. In view of this unrest, King wanted to force a nonviolent resistance in the north of the United States, which he first tried in Chicago . Here, however, he met resistance from leaders of local black organizations who did not accept his interference. In the metropolis in the north of the USA, the main problems were disproportionately high rents in the districts in which mainly blacks lived and the lack of equipment in schools. A rent boycott and demonstrations were intended to force the responsible politicians to act.

In the course of civil rights activities, Martin Luther King came up with the idea of imitating the symbolic action of his namesake Martin Luther, whose theses on Wittenberg from 1517, in Chicago. On the traditional “Freedom Sunday”, July 10, 1966, he gave a progammatic speech in front of “36,000 listeners” at the Soldier Field football and soccer stadium . Then he led the crowd to the town hall. He pinned 48 theses to the metal door amid cheers. […] While Martin Luther denounced the church's business-like indulgence trade in his 95 theses in 1517 in Wittenberg, King in Chicago in 1966 primarily denounced doing business with the underprivileged in the black ghetto of the big city. "King turned to those responsible in society and the economy and demanded Improvements in housing, education and employment.

“He called for public housing, kindergartens, a functioning garbage disposal, street cleaning and a building control service for the apartments in the ghetto that had been neglected by landlords and public toilets. He demanded apprenticeships and employment opportunities for blacks and Latinos not just at the lowest level, and a minimum wage of two dollars. He also called for a complaints office for police violence, police attacks and arbitrary arrests. Non-profit organizations should be co-financed by government funds. King also demanded that voting rights be enforced on the basis of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. "

At the rally, specific demands were made: double the budget for all schools, better transport connections for the ghettos and the construction of new districts with lower rents. There were many more demonstrations before a nine-point program was agreed, which, however, remained almost ineffective. On July 31, King was injured in the head by a brick during one of these demonstrations. The rent boycott had not led the apartment owners to give in either and rents remained unchanged. In 1966, King was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences .

March to Jackson

In 1966, a 350-kilometer march led by several black leaders, including King, took place from Memphis , Tennessee, to Jackson , the capital of the state of Mississippi. The first black graduate from the University of Mississippi , James Meredith , had been shot on the same march and plans to continue down the road in his honor. The demonstration, in which up to 15,000 people took part in the end, also wanted to protest for the consistent implementation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 .

During the march there was a strong propensity for violence and heated discussions between the leaders of the respective organizations on the issue of violence. Stokely Carmichael also announced the “ Black Power ” solution for the first time during a speech . In mid-April 1967, King led a demonstration of about 200,000 people through New York City, and in October 1967 he flew to Birmingham, where he was sentenced to a five-day sentence on an earlier sentence.

Vietnam War

From 1966, King turned more and more against the Vietnam War , which did not please all of his companions. Like many white Americans, large parts of the black population were on the side of the supporters of this war, and there was little support from the unions . Many civil rights activists feared that if the civil rights movement took sides against the war, it would harm itself because President Johnson would cut funds it needed. In addition, donations have decreased rapidly since the argument against the Vietnam War. But King did not back down, from then on he took the nonviolent path not only against racial segregation in the south, but also increasingly against poverty and war, a war whose American dead are buried in separate cemeteries for whites and blacks in the southern states of the USA had to be. In this context, he often argued that many billions of dollars would be invested in the war to solve major social problems. He tried to achieve better living conditions for all disadvantaged people, especially of course still for the black population.

King thus became a persona non grata in the White House and above all in the FBI under Chief Hoover . Cooperation with the anti-war movement and its white leaders as well as his plans, including in 1968 a Poor People's March (about: march of poor people ) to Washington to organize, found more and more critics. During this march, King wanted to stand up for the other minorities in the country.

attack

In view of the upcoming Poor People's March, a protest march in favor of striking garbage collectors, Martin Luther King decided to demonstrate first in Memphis , Tennessee, and to stand up again for (social) equality for all. Also, the Memphis visit could be seen as a kind of test of how strongly the masses would react to him.

On April 3, 1968, he said in his famous speech I've been to the mountaintop , that he the Promised Land (Original: Promised Land ) have seen and therefore nothing and no fear and therefore no worries about a long and fulfilling life more make. The formulation alludes to a passage in the book of Deuteronomy (34, 1–5) in which Moses, shortly before his death from Mount Nebo, sees the land of Canaan promised by God to the Israelites , but which he is unable to reach. Therefore the sentence was often interpreted as a prophetic premonition of death. King spoke to the protesters again to convince them of the non-violence and set April 8th as the new date for a demonstration.

On April 4, 1968 at 6:01 p.m. Martin Luther King was shot on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel by the racist James Earl Ray, who had several criminal records .

aftermath

After King's murder, riots broke out in over 110 cities in the United States, killing 39 people, injuring 2,000 and arresting 10,000 people. Washington DC in particular was hit by very serious unrest.

On April 8, 1968, Coretta Scott King led the protest march planned by her husband through Memphis. About 35,000 people took part in it peacefully. On the same day, President Johnson wanted to make a speech promising a major aid program for blacks. However, since the situation normalized soon after King's death and Congress protested, the speech was first postponed and then canceled entirely. On April 11, 1968, the United States Congress passed a law for equality in rental prices and home ownership ( Civil Rights Act of 1968 ; also known as the Fair Housing Act ).

In West Berlin, on April 12, 1968 at 3 p.m., a solidarity demonstration for “Black Power” was to take place on Lehniner Platz under the motto “Our patience too is over!”. However, the assassination attempt on Rudi Dutschke , which took place the day before only a few meters away, overshadowed this event and played a key role in determining the content of the demonstration.

burial

Martin Luther King Jr. was buried on April 9, 1968 in South View Cemetery, an Atlanta black cemetery. 50,000 people followed his coffin. In 1977 his relatives had him reburied near the King Center, where he is now buried with his wife. On his tombstone are the words of an old Negro Spiritual , with which he concluded his speech I have a dream - an “I” replaces the “we”: “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, I'm free at last! " ("Finally free! Finally free! Thanks be to God Almighty, I am finally free!") .

Many celebrities attended a funeral service in the church where he had served as pastor, such as then Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey , Senator Robert F. Kennedy , Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon, and New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller .

Legal processing and conspiracy theories

In front of the entrance to the motel opposite, a Remington rifle with the fingerprints of James Earl Ray was found, which the authorities classified as a murder weapon and which Ray is said to have dropped on his escape. The FBI and experts could only confirm at the time that the fatal shot was fired from a weapon of this type. At that time, however, the ballistic investigation methods were not yet mature enough to be able to assign the projectile used to a specific firearm. Ray confessed and was sentenced to 99 years in prison based on his confession. A few days later, however, he retracted his confession.

Since the attack, however, the rumors of a conspiracy by the American government, the CIA, the FBI, the mafia or militant supporters of the Vietnam War have never stopped. Investigations by the US Department of Justice , House of Representatives and prosecutors always came to the conclusion that Ray had shot and it was not certain whether he had helpers.

Two further, independent ballistic studies claim to have shown that it could not be conclusively proven that the weapon found (a Remington Gamemaster, Model 760, caliber 30-06) was actually the murder weapon, nor that Ray had fired it.

In 1999, the jury in a civil case agreed that King was a conspiracy between members of the Mafia and the US government. Another 18-month investigation by the Justice Department in 2000 rejected the results of this civil case on the grounds that it was based on hearsay and biased witnesses. Although there is no evidence of a conspiracy, not all of the inconsistencies in the case have been completely cleared up.

In 1995 William F. Pepper, the alleged perpetrator's lawyer, published the book Orders to Kill: The Truth Behind the Murder of Martin Luther King after decades of research . In 2003 he published An Act of State. The execution of Martin Luther King. A German translation was published in the same year (The Execution of Martin Luther King - How American State Power Silenced Its Opponent) .

King and the FBI

King had a mutually hostile relationship with the FBI , the primary investigative agency of the US Department of Justice . In particular, the then FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover harbored strong antipathies against the civil rights activist. The FBI began monitoring King and other SCLC officials in 1961. The investigation was rather superficial until it was found in 1962 that one of King's closest advisers was New York attorney Stanley Levison. Levison was suspected by the FBI of collaborating with the Communist Party of the United States , which was a warning signal for the federal agency given the anti-communism that was widespread at the time .

The FBI then placed eavesdropping devices in Levison's and King's homes and on their office phones, and bugged King's hotel rooms on his travels across the United States. The then President Kennedy and the then Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy were also informed, both of whom tried unsuccessfully to convince King to part with Levison. The black leader always adamantly denied all allegations that he had contact with communists . King once said: “ There are as many communists in this freedom movement as there are Eskimos in Florida” (for example: “ There are as many communists in this freedom movement as Eskimos in Florida” ), whereupon Hoover King as “ the most notorious liar in the country ” (“ the most notorious liar in the country ” ).

To publicly brand King as a communist, one built on the feeling of many segregationists that blacks are actually happy with their lot in society, but that communists or other "agitators" encourage them to protest. Leaders of some black organizations replied that often a lack of education and jobs, discrimination and violence are the reasons for the strength of the civil rights movement and that blacks have the intelligence and motivation to organize themselves autonomously .

The FBI later focused on discrediting King through revelations regarding his personal life. FBI surveillance of King (some have since been released) shows that he engaged in numerous extramarital affairs. Reports of such incidents were also provided by King's companions (including his close friend Ralph Abernathy). The FBI circulated these investigation results to the executive branch , friendly journalists, potential coalition partners, sources of funds from the SCLC and King's family.

Anonymous letters were also sent to King threatening that private information would be released if he did not stop his civil rights work. These activities took place as part of the FBI's secret program COINTELPRO , the aim of which was to wear down people classified as politically dangerous through methods such as anonymous discrediting .

Finally, let Kings personal life, and focused on intelligence information and the work of counterintelligence in terms of SCLC and the rest of the civil rights movement. Most of the results of the FBI's wiretapping work will not be available to the public until 2027. However, parts of the documents had previously been made public because US President Donald Trump had ordered government documents relating to the assassination of John F. Kennedy to be published. The historian David Garrow, who also published a biography of Martin Luther King, evaluated this and summarized it in an article for the British magazine Standpoint . Accordingly, the FBI recorded that King had orgies, frequented prostitutes and watched a rape.

On March 28, 1968, eight days before his death, a demonstration in Memphis led by King ended for the first time in riots, looting and fires, and police used tear gas.

FBI officials also observed him during the fatal assassination attempt on King. After King was shot, the FBI officers under surveillance were the first to rush to King and attempt first aid .

Questionable authorship

In the early 1980s there were allegations of plagiarism regarding King's doctoral thesis. An official investigation by Boston University found that King had copied parts of his doctoral thesis from other authors without marking it, according to academic conventions. Boston University decided not to retrospectively cancel the doctorate, as his doctoral thesis, despite the transcribed passages, contains its own part that represents an intelligent contribution to science. His doctoral thesis itself was given an addition, which indicates that parts of the doctoral thesis do not have the correct identification of the authorship.

Such "textual appropriation," as King scholar Clayborn Carson called it, was apparently a habit that stemmed from King's early academic career. He borrowed large parts of his speeches from other pastors or white Protestants who preached on the radio. While some political opponents criticized him for these findings, most scholars who have dealt with King have tried to put this "textual appropriation" into a larger context. Keith Miller, for example, an expert on plagiarism kings, argues that "such practices are part of the tradition of African-American popular sermons" and should not necessarily be labeled plagiarism.

Afterlife

Since his death, King's reputation has grown to become one of the most revered names in US history. He is often compared to Abraham Lincoln : both men were leaders who stood up for human rights and equal opportunities for all - and were murdered for this, among other things. Even published facts about the plagiarism in parts of his doctoral thesis and the allegation of marital infidelity could not seriously damage his reputation in public, but rather reinforced the image of a very human hero and leader. For example, King came third in a “Greatest Americans of All Time” poll on the US cable television station Discovery Channel . Pupils from two Berlin schools researched King's visit to Berlin in September 1964 and presented it in the King Code project.

Honors after death

1977 King was posthumously awarded the Medal of Freedom awarded ( "The Presidential Medal of Freedom"), the highest civilian award in the United States.

In 1978 he received the United Nations Human Rights Award .

In 1980 King's birthplace and a few other buildings in the area were declared a National Historic Site (about: Place of National Historic Interest).

In 1981 the asteroid (2305) King was named after him.

In 1986, not least at the instigation of the musician Stevie Wonder, a national holiday in honor of King was established, Martin Luther King Day , which is celebrated on the third Monday in January every year. On January 18, 1993, all governments of the 50 US states officially celebrated the holiday for the first time .

In 1987 the "Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Foundation" bought the Lorraine Motel and converted it into the "National Civil Rights Museum".

Since King's death, his wife Coretta Scott King has also been involved in areas such as social justice and civil rights. In the same year that King was murdered, she started the King Center in Atlanta. The aim was to preserve King's legacy and to commemorate his commitment to peaceful conflict resolution and global tolerance. King's son Dexter is currently the center's president and chairman of the board.

Many cities in the United States named one of their streets after the civil rights activist, and in Harrisburg , Pennsylvania, City Hall bears King's name. Schools and churches were named after him in the USA and many other countries . In 1968, the Martin Luther King Park in Amsterdam was named after him.

In 2010 another attempt was made to have King's likeness pressed onto US coins after civil rights activists unsuccessfully campaigned in 2000 to have King depicted on 50-cent coins or 20-dollar bills.

The band U2 wrote the songs Pride (In the Name of Love) and MLK (on the album The Unforgettable Fire ) in 1984 in honor of King and his life's work. However, Pride contains a historical error, because King was not, as implied in the play, murdered in the morning, but in the evening. U2 singer Bono sings the song in a corrected version during live performances .

James Taylor dedicated the song Shed a Little Light to King in 1991 .

A lava flow of the Puʻu ʻŌʻō (Martin Luther King flow) that was active in January 2004 and formations derived therefrom are usually abbreviated as MLK .

On August 22, 2011, the " Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial " was opened to visitors in Washington's Tidal Basin on the National Mall . It was only inaugurated by President Obama on October 16, 2011, after the inauguration originally planned for August 2011 had to be postponed due to Hurricane Irene . After George Washington , Thomas Jefferson , Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt , King is the fifth American to be dedicated to a memorial in Washington, as well as the first African-American.

On January 8, 2018, President Donald Trump signed the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park Act, which upgrades the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Site to a National Historical Park. It's first National Historical Park in Georgia. As part of this upgrade, the Prince Hall Masonic Temple was added as a memorial.

Memorial days

- ecclesiastical:

- state:

- United States of America: third Monday in January ( Martin Luther King Day ), since 1986.

Kings role in the civil rights movement in the US

Before King was exclusively committed to civil rights, the NAACP in particular campaigned for the rights of the black minority.

With the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1956, King's influence on the civil rights movement and his person's impact on the black population increased sharply. Previously he was mainly active as a pastor, but in the following years he traveled with interruptions throughout the United States and gave countless speeches. The successes in Birmingham, the enforcement of the Civil Rights Act 1964 and the award of the Nobel Peace Prize made King the greatest leader of the nonviolent protest for black equality, which can also be measured against the 250,000 participants in the march on Washington that he led . In these years the NAACP also lost a lot of its importance.

But there was also criticism of King's leadership role and of his principle of protesting exclusively non-violently. In 1960, for example, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was founded, which constructively criticized the role of Kings in the nationwide movement. When Stokely Carmichael became chairman of the SNCC in 1965 , their political course became radicalized towards militant, black nationalism; Carmichael's successor eventually changed the association's name to Student National Coordinating Committee . In 1964 Malcolm X set up the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU). In his speech on the founding day, he openly called for the settlement of exclusively nonviolent strategies and thus clearly distanced himself from King. However, more than the small OAAU, which broke up after Malcolm X's death in 1965, the speeches of the noted founder influenced the black movement.

In 1966 the Black Panther Party was formed , which tried less through mass protests than through aid for black people in need to compensate for social injustices. In addition, she advocated “black nationalism” and the express right to defend oneself, and thus distinguished herself from King's pacifism and tolerance thinking. Then in 1966, on the initiative of Carmichael, the loosely separatist Black Power movement was brought into being, which aimed to unite all blacks and to preserve “black culture”. King also frequently clashed with Roy Wilkins , the then leader of the NAACP and well-known civil rights activist. Nonetheless, Wilkins took part in various demonstrations, such as the march to Washington, and was critical of militant organizations.

It was primarily because of such groups that King's ideals and protest actions had a difficult time in the north of the USA. In addition, he only began to organize demonstrations in a northern city, Chicago, in 1966. Nevertheless, he remained the undisputed leader of nonviolent resistance for many until his death.

Due to the assassination attempt, the increased pressure from the FBI (above all on the Black Panther movement) and the political concessions, the civil rights movement in the USA paralyzed after 1970. The SNCC disbanded in 1970, and the Black Panthers ceased to appear publicly from 1981. The NAACP and the SCLC still exist today.

Works

- A comparison of the conceptions of God in the thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman . Dissertation, 1955

- Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story . 1957 (German: "Steps to Freedom: The Montgomery Story"). English reprint (paperback) 2010, Beacon Press, ISBN 978-0-8070-0069-4 .

- The Trumpet of Conscience (1967). German translation: Call to civil disobedience. 1st edition. Econ, 1969 (1993, ISBN 3-612-26036-7 )

- Call to civil disobedience . Econ-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1993, ISBN 3-612-26036-7 .

- Freedom. On the practice of nonviolent resistance . Brockhaus, Wuppertal 1982, ISBN 3-417-20332-5 .

- Peace is not a gift. About the power of non-violence . Herder, Vienna 1984, ISBN 3-210-24776-5 .

- I've been to the top of the mountain. Talk . Edition Nautilus, Hamburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-96054-021-2 .

- I have a dream. Texts and speeches . Kiefel Verlag, Gütersloh 1996, ISBN 3-7811-5777-6 .

- I have a dream . Patmos-Verlag, Düsseldorf 2003, ISBN 3-491-45025-X .

- My dream of the end of hatred. Texts for today . Herder, Freiburg / B. 1994, ISBN 3-451-04318-1 .

- Creative resistance . Mohn, Gütersloh 1985, ISBN 3-579-00576-6 .

- Testament of Hope. Final speeches, essays and sermons . Mohn, Gütersloh 1989, ISBN 3-579-05079-6 .

- A dream lives on . Mohn, Gütersloh 1986, ISBN 3-451-08285-3 .

- Where does our way lead? Chaos or community . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1969.

literature

- Hans-Eckehard Bahr: Martin Luther King. For another America . Structure, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-7466-8123-5 .

- Clayborne Carson (Ed.): The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Abacus, London 2000.

- Richard Deats: Martin Luther King. Dream and deed. A picture of life . Neue Stadt, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-87996-763-6 .

- Tobias Dietrich: Martin Luther King . Fink, Paderborn 2008, ISBN 978-3-8252-3023-4 , (UTB 3023).

- Adam Fairclough: Martin Luther King, Jr. University of Georgia Press, Atlanta 1995, ISBN 978-0-8203-1653-6 .

- David Garrow: The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr. Penguin, New York 1981, ISBN 0-14-006486-9 .

- Frederik Hetmann : Martin Luther King . Maier, Ravensburg 1993, ISBN 3-473-54099-4 . (Youth book)

- Martin Luther King Sr.: Departure into a better world. The story of the King family . Union, Berlin 1984

- Coretta Scott King: My life with Martin Luther King . Gütersloher Verlagshaus Mohn, Gütersloh 1985, ISBN 3-579-03643-2 .

- Rolf Italiaander : Martin Luther King . Colloquium, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-7678-0674-6 .

- Stanislaw N. Kondrashov: Martin Luther King. Life and Struggle of an American Negro Leader . German Science Publishing House, Berlin 1973.

- Stephen B. Oates: Martin Luther King, Fighter for Nonviolence . Heyne, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-453-55140-0 .

- William F. Pepper: The Execution of Martin Luther King. How the American government silenced its opponents . Diederichs / Hugendubel, Munich a. a. 2003, ISBN 3-7205-2405-1 . (Review by Joachim Scholtyseck in the FAZ of September 15, 2003 under the title Without files, without facts .)

- Gerd Presler : Martin Luther King , rowohlt (rororo), Reinbek near Hamburg 1984 (18th edition 2017).

- Valerie Schloredt, Pam Brown: Martin Luther King. America's great nonviolent leader who was assassinated fighting for black rights. 2nd Edition. Arena, Würzburg 1990, ISBN 3-401-04278-5 . (Youth book)

- Hans Jürgen Schultz : “I tried to love.” Portraits. From people who thought peace and made peace: Martin Luther King, Dietrich Bonhoeffer , Reinhold Schneider , Albert Schweitzer . Quell, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-7918-2020-6 . (First edition Partisans of Humanity. )

Video and audio material

- Collection of video and audio files (English website)

- I've been to a mountaintop - speech as MP3 on americanrhetoric.com

- I Have a Dream - Speech as MP3 on americanrhetoric.com

- (Audio mp3) Pepper author describes the circumstances of the murder (English)

- Christian Blees: "I was on the top of the mountain." The assassination attempt on Martin Luther King. Radio feature , April 4, 2008, production: SWR , RBB , ORF , online file , (74.1 kB; RTF )

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in His Own Words on democracy.org on January 16, 2012 (video, 59 min., English)

Filmography

- Then my life wasn't in vain - Martin Luther King documentary, 1970, 135 min., Directors: Sidney Lumet and Joseph L. Mankiewicz

- Martin Luther King - Murder by State Order. Documentation, 2004, 52 min., Written and directed: Claus Bredenbrock and Pagonis Pagonakis , production: arte , ZDF , first broadcast: October 27, 2004, summary by arte

- Dr. King, civil rights activist. Part 1: "I Have a Dream", (OT: American Experience. Citizen King ), documentary, USA, 2004, 55 min., Script and director: Noland Walker, Orlando Bagwell, production: Roja Productions Inc. for PBS , Summary of arte, original movie site of PBS

- Dr. King, civil rights activist. Part 2: “I Have Seen the Promised Land”, documentary, USA, 2004, 58 min., Script and director: Noland Walker, Orlando Bagwell, summary by arte

- The documentary paints the political portrait of King from 1963 until his assassination in 1968.

- The 2001 racism drama Boycott takes up the events of Rosa Parks, ML King Jr. and the Montgomery Bus Boycott .

- Selma , 2014 feature film, covers King's role during the Selma to Montgomery Marches .

- Raoul Peck (Script, Director): I Am Not Your Negro . The documentary based on the unfinished manuscript by J. Baldwin sheds light on the controversy with Malcolm X (Black Muslims). USA, Fri, De, 2017; 94 min.

Web links

- Literature by and about Martin Luther King in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Martin Luther King in the German Digital Library

- Collection of articles with texts by and about King on the Lebenshaus website

- The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Educations Institute (many original texts)

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1964 award ceremony for Martin Luther King Jr.

- Martin Luther King Center Germany

- Martin Luther King at Discogs (English)

- The Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i rundfunk.evangelisch.de: A momentous journey (January 14, 2017)

- ↑ Peter J. Ling: Martin Luther King, Jr. Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0-415-21664-8 , pp. 11 . ( Excerpt (Google) )

- ^ Clayborne Carson: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. p. 9: “We cannot have an enlighted democracy with one great group living in ignorance. We cannot have a healthy nation with one-tenth of the people ill-nourished, sick, harboring germs of disease which recognize no color lines - obey no Jim Crow laws. "

- ↑ a b Stephen B. Oates: Martin Luther King, Fighter for Nonviolence . Heyne, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-453-55140-0 , pp. 24, 30-32.

- ^ Clayborne Carson: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. p. 13.

- ↑ King at Crozer Theological Seminary ( Memento of the original from April 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (1970 merger with Colgate Rochester Divinity School in Rochester, NY)

- ^ Clayborne Carson: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. p. 19: “I see preaching as a dual process. On the one hand I must attempt to change the souls of individuals so that their societies may be changed. On the other I must attempt to change the societies so that the individual soul will have a change. Therefore, I must be concerned about unemployment, slums and economic insecurity. "

- ↑ Clayborne Carson: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. p. 22: “My reading of Marx also convinced me that the truth is found neither in Marxism nor in traditional capitalism. Each represents a partial truth. Historically capitalism failed to see the truth in collective enterprise and Marxism failed to see the truth in individual enterprise. Nineteenth-century capitalism failed to see that life is social and Marxism failed and still fails to see that life is individual and personal. The Kingdom of God is neither the thesis of individual enterprise nor the antithesis of collective enterprise, but a synthesis which reconciles the truth of both ”

- ↑ Clayborne Carson: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. p. 24: "It was in this Gandhian emphasis on love and nonviolence that I discovered the method for social reform that I had been seeking."

- ^ Clayborne Carson: The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. p. 27: “While I still believed in man's potential for good, Niebuhr made me realize his potential for evil as well. Moreover, Niebuhr helped me to recognize the complexity of man's social involvement and the glaring reality of collective evil. "

- ^ Boston U. Panel Finds Plagiarism by Dr. King . New York Times , October 11, 1991. A college committee examined the dissertation (the dissertation still “makes an intelligent contribution to scholarship”).

- ^ Steven Levingston: John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Phone Call That Changed History. Time, June 20, 2017, accessed July 28, 2020 .

- ↑ Christopher Klein: 10 Things You May Not Know About Martin Luther King Jr.History.com, April 4, 2013, accessed July 28, 2020 .

- ↑ King biographer Stephen B. Oates writes (Biography. P. 203) that Kennedy received "almost three quarters of the Negro votes".

- ↑ after Joan Baez sang it in front of an audience of 300,000 on the March on Washington for Work and Freedom

- ^ "Negroes to Defy Ban," Tuscaloosa News , April 11, 1963.

- ↑ a b Rieder, Gospel of Freedom (2013), chapter Meet Me in Galilee

- ↑ Rieder: Gospel of Freedom (2013), chapter Meet Me in Galilee . “King was placed alone in a dark cell, with no mattress, and denied a phone call. What is Connor's aim, as some thought, to break him? "

- ↑ full text

- ↑ full text

- ↑ Jürgen Dittrich: Forever King - the myth of Martin Luther King lives on . Article in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung from November 11, 2002

- ^ Gerd Presler: Martin Luther King. With testimonials and photo documents . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2005, ISBN 3-499-50333-6 , p. 92.

- ↑ The story: Martin Luther King in East Berlin. In: Der Tagesspiegel. September 6, 2009.

- ↑ spiegel.de / one day: "Let my people go!"

- ↑ king-code.de

- ↑ Text of his speech when receiving the award ( memento of the original from March 15, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Robert Dallek: Lyndon B. Johnson: Portrait of a President . Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-515921-7 , pp. 234ff.

- ↑ American President: Lyndon B. Johnson - Domestic Affairs

- ^ Georg Meusel: The posting of theses in Chicago . evangelisch.de, July 10, 2016, accessed on July 11, 2016.

- ↑ a b Stephen B. Oates: Martin Luther King, Fighter for Nonviolence . Heyne, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-453-55140-0 , pp. 579-583.

- ↑ Gerd Presler: Martin Luther King Jr. With self-testimonies and picture documents. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2005, ISBN 3-499-50333-6 , p. 133.

- ↑ Jürgen Dittrich: Forever King - the myth of Martin Luther King lives on . In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. November 11, 2002.

- ↑ a b Jürgen Schönstein: Who Killed Martin Luther King? Die Welt, February 22, 1997, accessed July 23, 2020 .

- ^ Christian Blees: Death of a civil rights activist. Deutschlandfunk, April 3, 2008, accessed on July 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Michael Schwelien: The family of Martin Luther King want to reopen the murder case of 1968. Die Zeit, April 11, 1997, accessed on July 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Matthew B. Robinson: King, Martin Luther, Jr., Assassination of. In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . ABC Clio, Santa Barbara / Denver / London 2003, Volume 1, pp. 402-410.

- ^ ISBN 0-7867-0253-2 .

- ↑ English: Verso, New York 2003; German: Hugendubel, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-7205-2405-1 .

- ↑ Supplementary detailed Staff Reports on Intelligence Activities and the Rights of Americans , BOOK III (from the final report of the Church Committee )

- ↑ David J. Garrow: The troubling legacy of Martin Luther King. Standpoint, May 30, 2019, accessed on June 2, 2019 .

- ↑ APM report on King, https://features.apmreports.org/arw/king/c1.html , accessed on July 21, 2020 (English)

- ^ List of previous recipients. (PDF; 43 kB) United Nations Human Rights, April 2, 2008, accessed on December 29, 2008 (English).

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 6208

- ↑ MLK Flow from January 18 to 24, 2004, MLK breakout, MLK pit, MLK vent; see. Tim R. Orr: Studies of Recent Eruptive Phenomena at Kīlauea Volcano . Ph.D. - Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2015, http://hdl.handle.net/10125/51219 , pp. 9, 13, 15, 25.

- ^ Huffington Post, online October 16, 2011. ( January 17, 2014 memento on the Internet Archive ) Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Mark Pitzke: Monument to Martin Luther King. America honors its greatest dreamer on Spiegel Online on August 24, 2011.

- ↑ Mashaun D. Simon, NBC NEWS: Trump designates Martin Luther King Jr. birthplace a national historic park , accessed April 30, 2020.

- ↑ Martin Luther King in the ecumenical dictionary of saints

- ↑ https://www.perlentaucher.de/buch/william-f-pepper/die-hinrichtung-des-martin-luther-king.html

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | King, Martin Luther |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | King, Martin Luther Jr. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American theologian and civil rights activist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 15, 1929 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Atlanta , Georgia |

| DATE OF DEATH | 4th April 1968 |

| Place of death | Memphis , Tennessee |