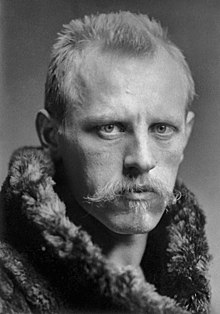

Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (born October 10, 1861 in Store Frøen near Christiania, today Oslo ; † May 13, 1930 in Lysaker ) was a Norwegian zoologist , neurohistologist , polar researcher , oceanographer , diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize laureate .

Nansen studied zoology at the University of Christiania and later worked as curator of the Bergen Museum , where he wrote a doctoral thesis on the central nervous system of marine invertebrates , which made significant contributions to the foundations of modern neurology . From 1897 he devoted himself to the then still young research discipline oceanography, undertook several research trips mainly to the North Atlantic and was involved in the development of equipment for marine research.

In his work as a polar explorer, he was the first to cross Greenland across the ice sheet in 1888 and set a new record with Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen on April 8, 1895 during his north polar expedition (1893–1896) with a latitude of 86 ° 13.6 'N the closest achieved approach to the geographic North Pole . He revolutionized the techniques of polar travel and thus influenced all subsequent expeditions in the Arctic and Antarctic .

As one of the most respected citizens of his country, Nansen played a key role in the efforts to achieve political independence in Norway. In 1905 he was a strong advocate of ending the Swedish-Norwegian personal union that had existed since 1814 and helped enthrone the then Prince of Denmark as King Haakon VII of Norway . Between 1906 and 1908, Nansen worked in the diplomatic service in London , where he worked on was involved in the negotiations on the recognition of Norway's sovereignty under international law .

In the last decade of his life, Nansen served as a delegate and high commissioner for refugee issues for the League of Nations founded after the First World War . During this time he initiated the Nansen Pass, named after him, for stateless refugees. For this and for his services to international refugee aid, he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922 .

Origin, childhood and youth

Nansen's ancestors came from Denmark . They include the businessman and future mayor of Copenhagen Hans Nansen (1598–1667), who took part in early exploratory trips to the White Sea region to develop new trade routes to Russia and is the author of the 1633 Compendium Cosmographicum geographical handbook . The first family member residing in Norway was Nansen's great-grandfather Ancher Antoni Nansen (1729–1765), who left Copenhagen for his new home in the 1750s. His son, Hans Leierdahl Nansen (1764-1821), was first a magistrate in the Trondheim district and later in Jæren . After Norway gained independence from Denmark through the Peace of Kiel on January 14, 1814, he became a member of the Storting . There he was one of the advocates of the Swedish-Norwegian personal union that emerged from the Swedish-Norwegian War in August 1814, and his grandson helped to dissolve it 91 years later.

Fridtjof Nansen was born in 1861 as the second child of the wealthy lawyer Baldur Nansen (1817–1885), the son of Hans Leierdahl Nansen, and his second wife Adelaide Johanne Thekla Isidore Wedel-Jarlsberg (1821–1877) on the Store Frøen estate (freely translated: The great fertile meadow ) north of Christiania. Their first son, whom they had also baptized Fridtjof, was born in 1859, but died in infancy. The third child was Fridtjof's younger brother Alexander (1862–1945). Nansen's mother was the niece of Hermann von Wedel-Jarlsberg , who is one of the fathers of the Norwegian constitution . Widowed Adelaide, whose first husband died of cholera in 1853 , brought five children (three sons and two daughters) into their marriage to Baldur Nansen in 1858. From Baldur Nansen's previous marriage came a son named Moltke (1854–1867). Baldur's first wife died of puerperal fever shortly after giving birth .

Nansen's childhood and adolescence were shaped by the rural surroundings of his parents' home. From 1868 he attended school in Christiania and was considered a hardworking student, but without developing any particular preferences for a subject. His pastimes included hunting and fishing. At times he undertook extensive expedition hikes through the neighboring forests of the Nordmarka, where he lived "like Robinson Crusoe " in his own words . The upbringing of his deeply religious father instilled in him a sense of duty and moral principles. Guided by his sporty mother, he was an avid swimmer , speed skater and skier from an early age . At the age of ten he started on the hills of Ullern with the ski jumping , making it nearly cost the life. Nansen survived a serious fall almost uninjured. Despite this incident, the passion for winter sports remained unbroken. At Christmas 1882 he skied a tour that was tantamount to a forced march , from Bergen to Christiania and back. Some sources also report that he won the national cross-country skiing championships twelve times and set a world record in speed skating over the distance of one mile at the age of 18 .

Nansen's life experienced a turning point in the summer of 1877 when his mother died unexpectedly. His father sold the family seat Store Frøen and moved to Christiania with his underage sons Fridtjof and Alexander.

Study time

After completing the Latin school in Christiania and passing the Abitur examination in 1880 , Nansen initially registered as a cadet at the war school . With the intention of studying medicine at the Kongelige Frederiks Universitet in Christiania, he withdrew his registration. In the end he decided to study zoology because, according to his own statement, he hoped that this would enable him to lead a life in the great outdoors, and he enrolled in 1880. His studies began in the spring of 1881. In the following year, Nansen decided “to a [ …] Momentous step that led me off the right path of a peaceful scientific life. ”His lecturer, the zoologist Robert Collett (1842–1913), suggested that he go on an expedition into arctic waters to carry out zoological studies on site . Nansen took up this suggestion enthusiastically and made preparations for a trip on board the sealer Viking under Captain Axel Krefting (1850–1886), whom he had met shortly before. The journey began on March 11, 1882 and lasted five months. In the weeks leading up to the seal hunt, Nansen conducted oceanographic studies. Using experimental approaches, he was able to prove that ice formation in seawater takes place on the surface and not, as previously assumed, in deeper layers. He also found out that the warm Gulf Stream runs beneath a layer of cold salt water. The Viking crossed in search of flocks of seals at the start of the trip in the waters between Greenland , Jan Mayen and Spitsbergen . When hunting, he proved to be a good shot. Nansen recalled that his hunting party hunted 200 seals in one day. In July, the Viking was trapped by pack ice within sight of a previously unmapped region of the Greenland coast . Nansen's wish to reach the coast on foot across the sea ice was not fulfilled. Captain Krefting refused his request to be allowed to attempt a landing, as he feared that when the ice broke, Nansen would not return to the ship in time for the onward voyage. During this time, Nansen developed the idea of examining the interior of Greenland or even crossing the island over the ice sheet . The Viking was released from the pack ice on July 17, 1882 and returned to Norway in August.

Nansen did not resume his formal studies at the university after his return. Instead, he became curator of the zoological department of the Bergen Museum on Collett's recommendation in the fall of 1882 . In total, Nansen held this position for six years. In Bergen he met such well-known researchers as Gerhard Armauer Hansen , the discoverer of the leprosy pathogen , and Daniel Cornelius Danielssen , who, as director of the Bergen Museum, had transformed it from a backward natural history collection into an important research and training facility. After Nansen first anatomical and histological studies of bristle worms from the family of Myzostomidae had made and for this purpose published an extensive work in 1885, he specialized in the field of until then virtually unedited neuroanatomy . He was particularly interested in the central nervous system of morphologically original marine chordates ( sea squirts and hagfish of the species Myxine glutinosa ). During a trip abroad as part of a sabbatical between February and August 1886, he visited Ernst Haeckel in Jena and learned from Camillo Golgi in Pavia the technique known as “reazione nera” (German: “black reaction”) for the preparative staining of nerve tissue using silver nitrate ( Golgi Staining ) and was the first to depict the entire neuroglia of the spinal cord in a vertebrate ( Myxine glutinosa ). In a first publication of his research work, he proposed that there were no reliable findings about the “ anastomosis or associations of the various ganglion cells ”. Nansen's work formed one of the foundations for the so-called "neuron theory" for the structure of the nervous system, according to which the nerve pathways consist of individual cells that communicate with each other. His results were confirmed by the simultaneous work of the embryologist Wilhelm His and the brain researcher Auguste Forel . In 1887 he published the structure and connection of the histological elements of the central nervous system , which he defended in 1888 as his dissertation .

Crossing Greenland

Planning and preparation

The idea to cross Greenland came about during Nansen's trip on the Viking . Bound by his work at the Bergen Museum and a temporary stay at the Naples Zoological Station , he was only able to resume his plans after completing his doctoral thesis. Before him, Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (1883) and Robert Peary (1886) had already undertaken forays into the interior of the island from Disko Bay on the west coast over a maximum distance of around 160 km. In contrast to their approach, Nansen intended to cross Greenland from east to west. He thought it was less of a risk to drop a crew on the uninhabited east coast with the ship instead of having to pick them up there after a crossing. Since the voyage with the Viking , he had known the conditions encountered there, in which a ship ran the risk of being trapped by pack ice or being damaged by the towering ice masses caused by the prevailing ocean currents. In addition, so Nansen's consideration, the crew would be forced to continue on their way west in any case due to the lack of opportunities to retreat: “If they were to start from the west, [...] it would be almost certain that they would never get over . The meat pots of Egypt lay behind them and in front of them the unexplored ice desert [...]. "

Nansen rejected the practice of previous expeditions of proceeding with a large number of participants and high material costs. Instead, his crew consisted of only six men. He intended to transport equipment and supplies on specially prepared sleds. Much of the equipment, including clothing, sleeping bags and cooking utensils, was custom-made by Nansen according to his own designs. The press commented on his plans, which he had announced in January 1888 in the Norwegian magazine Naturen , with skeptical or negative comments . In an article in the Danish magazine Ny Jord , the author had no doubt, “Should Nansen's plan be implemented in its present form, […] there is a ten-to-one chance that he will […] his life and possibly that of others entirely throws away pointlessly [...]. ”The Norwegian Parliament refused to provide financial support in the opinion that such a risky project should not be upgraded. Nansen brought the necessary funds together through a donation from the Danish businessman Augustin Gamél (1839–1904) and through a collection that Norwegian students had carried out for him.

Despite the negative public response, Nansen received numerous applications to participate in his expedition. His hope of being able to recruit experienced skiers from Telemark , however, was not fulfilled. Nordenskiöld advised him to draw on the experience of the Sami from Finnmark in northern Norway , and so Nansen took two of them, Samuel Johannesen Balto (1861-1921) and Ole Nilsen Ravna (1841-1906), into his team. The other participants were the former ship's captain Otto Sverdrup , who last worked as a casual worker in wood and forestry, his friend, the farmer Kristian Kristiansen Trana (1865-1943), and the army officer Oluf Christian Dietrichson (1856-1942 ). All expedition members were familiar with dealing with extreme cold and mastered skiing. The expedition set out before Nansen had found out about the results of his disputation .

Expedition trip

On June 3, 1888, Nansen's crew went on board the sealer Jason under captain Johan Mauritz Jacobsen (1853-1945) in Iceland's Ísafjörður . On June 11th, the east coast of Greenland came into view for the first time. However, thick pack ice prevented a direct landing. When the ship had approached the coast within 20 km on July 17, Nansen and his men boarded two dinghies in the hope of using ice-free canals to reach Sermilik near Tasiilaq , which could be an ascent route to the Greenland ice sheet.

According to Captain Jacobsen, the crew left Jason "in a good mood and with the greatest hope of a happy ending", but the first few days were marked by failures and disappointments. The direct route to the coast was blocked by thick ice. Bad weather and a strong current also drove the men far south. Most of the time they spent on the ice, as they were in danger of overturning in the boats due to ice pressure. On July 29th, the six men were about 380 km south of the position where they left the Jason . They reached the coast on the same day, but too far south to begin the planned crossing. After a short rest, Nansen ordered the men to row north in the boats.

For the next twelve days they made their way along the coastline through floating ice. On the first day they met a larger Inuit settlement near Cape Bille ( 62 ° 0 ′ N , 42 ° 7 ′ W ), and on the following days they also met a few local people. On August 11, after 200 km to the north, they had reached the Umiivikfjord ( 64 ° 19 ′ N , 40 ° 36 ′ W ). Although they were still a long way from their planned starting point, Nansen decided to start the march from here, given the advanced time of the year. After a few days of preparation, the expedition members set out on the evening of August 15th. Their destination, the settlement of Christianshåb in Disko Bay, was 600 km to the northwest from them.

In the first days of their march, the men struggled with their sleds in tow in a continuous ascent on ice with hidden crevasses inland. The weather was mostly bad; in the meantime, the team was stopped by a violent storm and continuous rain. On August 26th, Nansen realized that their chances of getting to Christianshåb by mid-September were negligible, so that they could reach the last ship there in time for their return voyage. He decided to head straight west to Godthåb , which was 150 km away from them. Nansen representation "welcomed [the team] amending the plan with applause." The climb up the ice sheet continued until September 11, when night temperatures of -46 ° C at an altitude of 2719 meters above the sea reached. From then on, their way became easier with a slight incline, although the terrain remained unpredictable and the weather unpleasant. Fresh snow, which, according to Nansen's description, was so dull as if one were pulling the sledge over sand, made it difficult for them to advance. On September 26, the men reached the Ameralikfjord ( 64 ° 7 ′ N , 51 ° 0 ′ W ). Using willow rods, parts of their tents and a transport sledge, they made a makeshift boat in which Nansen and Sverdrup set off on the last leg of their journey on September 29th. After a further 100 km, both men finally reached Godthåb on October 3rd, where they were greeted by the Danish governor . From this Nansen learned that he had been awarded the doctorate (Norwegian: dr. Philos., English: Ph.D. ); a matter "which at that moment couldn't have been further from my thoughts." It had taken them 49 days to march through Greenland; a total of 78 days had passed since the crew left Jason . Two boats were sent out to fetch the rest of the expedition. On October 12th the men were reunited.

In the meantime autumn was so far advanced that no ship left Godthåb for Europe. Nansen commissioned an Inuk to kayak to Ivigtût, 300 km south, and to send news about the successful course of the expedition with the last transport ship to Denmark and Norway. For Nansen's and Sverdrup's later ventures, the forced stay turned out to be favorable. During the seven-month winter in Godthåb, they studied the Inuit way of life and learned techniques for survival in the Arctic and the use of dog sleds as a means of transport. Nansen later recorded his memories of the time together with the Inuit in the book Eskimoliv (German version: Eskimoleben ). On April 25, 1889, Nansen and his men on board the Hvidbjørnen from Godthåb first went to Denmark, "[...] not without regret [to leave] this place and these people, among whom we felt so comfortable." After a stopover in Copenhagen the expedition members met on board the post ship M. G. Melchior , which was accompanied by hundreds of boats on its journey through the Christianiafjord , on May 30, 1889 in Christiania.

With his expedition, Nansen was able to prove that the interior of Greenland is covered by snow and ice. Added to this were new findings and observations on geography and, above all, on the extent and movement of the Greenland glaciers. His measurements contributed to a better understanding of the meteorological conditions and the development of weather in Europe and in the northern Atlantic .

Time after the Greenland expedition and marriage

Nansen and his men were received in Christiania by around 40,000 onlookers , around a third of the city's residents. Nansen's news about the success of the Greenland expedition had already arrived in Denmark and Norway last October. The enthusiasm and interest in the successes of the expedition led to the founding of the Norwegian Geographical Society in the same year . In addition, skiing gained enormous popularity in Norway through Nansen's crossing of Greenland.

As a result, Nansen accepted a position as curator of the zoological collection of the University of Christiania, which did not oblige him and ensured a regular income. The university contented itself with adorning itself with Nansen's good name. His main self-imposed task was to publish the results of his Greenland expedition. In June 1889 he visited London, where there was a meeting with the English heir to the throne, Prince Albert Edward , and he attended a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society . Its president, Sir Mountstuart Grant Duff (1829–1906), declared that Nansen had assumed "the leading position among all travelers to the north" and awarded him the Society's Medal of Patronage in recognition of his services. This was just one of many awards Nansen received across Europe. These included the Knight's Cross of the St. Olav Order , the Dannebrogorden (knight 1st class), the Carl Ritter Medal from the Society for Geography in Berlin and the Vega Medal from the Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography . An offer to participate in an Antarctic expedition was made to him from Australia. However, he refused, convinced that he would better represent Norway's interests if his goal was to reach the North Pole.

On August 11, 1889, Nansen announced the engagement to Eva Sars (1858-1907), the youngest daughter of the Norwegian zoologist Michael Sars and sister of the zoologist Georg Ossian Sars . Her mother Maren Cathrine Sars (1811–1898) was the sister of the poet Johan Sebastian Welhaven . After training with Désirée Artôt, Eva was a successful mezzo-soprano . She and Nansen had met a few years earlier while skiing in Frognerseteren, not far from Holmenkollen . The engagement came as a surprise to many of his friends and acquaintances, as Nansen had previously shown himself to be an opponent of the institution of marriage . The wedding took place shortly after the engagement on September 6, 1889. The marriage produced five children: Liv (1893–1959), Kåre (1897–1964), Irmelin (1900–1977), Odd (1901–1973) and Asmund (1903–1913).

Fram expedition

Background and preparations

Even before his Greenland expedition, Nansen had the idea of another research trip. The background for this was provided by the theory of a transpolar drift flow developed by the Norwegian meteorologist Henrik Mohn . Nansen believed that the ice drift in the Arctic Ocean caused by ocean currents enabled a specially designed ship to get trapped in the pack ice near the North Pole. His plans, which he disclosed to the Norwegian Geographical Society in February 1890 and which met with skepticism and rejection in the professional world, provided for the expedition ship and a small, well-trained crew to advance to the New Siberian Islands and freeze the ship there and then expose it to the ice drift for the further journey north.

With the help of public and private sponsors, Nansen had the expedition ship Fram built between June 1891 and October 1892 according to plans by the Norwegian designer Colin Archer . The special hull construction with an oval cross-section and other technical features should ensure that the ship is not damaged in the pack ice, but can, in Nansen's words, "slide like an eel out of the embrace of the ice".

The team of thirteen included Nansen, the veteran of the Greenland expedition Otto Sverdrup as captain of the Fram and Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen . The latter later also took part in the successful South Pole expedition led by Roald Amundsen .

Expedition course

On July 21, 1893, the expedition team on board the Fram Vardø , the last Norwegian intermediate port , left for the eastern Barents Sea . Nansen and his men followed the course of Nordenskiöld's Northeast Passage . After driving along the north-west Russian and north Siberian coastlines, they reached the northern end of the Taimyr Peninsula in late August . After pack ice had prevented a further voyage in the meantime, the Fram circled Cape Chelyuskin on September 9, 1893 and entered the Laptev Sea . Finally, on October 5th, after being completely enclosed in the pack ice, the ship was "thoroughly and conscientiously moored for the winter at 79 ° N , 133 ° E west of Kotelny Island ."

The ice drift initially turned out to be a sobering undertaking, as neither the direction nor the speed of the drift corresponded to Nansen's calculations. On November 19, after six weeks of ice drift, the ship was further south than at the beginning, and only on February 2, 1894 did it cross 80 ° north latitude. Nansen calculated that it could take up to five years for the ship to reach the North Pole in this way. So he decided to leave the Fram at a convenient time to reach the North Pole with Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen with the help of skis and sled dogs. He chose Franz-Josef-Land as a retreat , where she was supposed to pick up the Fram for the journey home.

On March 14, 1895, when the Fram had reached a latitude of 84 ° 4 'N, Nansen and Johansen set out on foot for the North Pole with two kayaks , three transport sleds and 28 sled dogs. Nansen planned to cover the missing 660 km to the North Pole within 50 days, which corresponded to a daily workload of 13 km. After both men had covered the first 120 km at around 17 km per day, the terrain became increasingly uneven, which made it difficult to advance on skis and reduced their travel speed. In addition, position determinations showed that they were marching against a southern ice drift and that the daily distances traveled did not necessarily bring them closer to their destination. The cold with temperatures of −40 ° C also hit them. Johansen's diary reveals the increasing discouragement of both men at this point in time: “All my fingers have been destroyed. The gloves are frozen stiff… It's getting worse and worse… God knows what will become of us. ”After they set up camp on April 7th, Nansen set out on a scouting tour for their further journey north, but the only thing he saw was was "a real chaos of ice blocks that stretched to the horizon." The last position determination on April 8th showed a north latitude of 86 ° 13.6 ′, which they had exceeded the previous north record by almost three degrees of latitude. Nansen decided not to go any further and instead headed for Cape Fligely on Franz-Josef-Land.

For Nansen and Johansen, the way back was an arduous, dangerous and, above all, lengthy undertaking. On July 24, 1895, for the first time since leaving the Fram, the men sighted a land mass “after we had almost given up our belief in it!” On August 7, after reaching the ice edge, they crossed over there in the kayaks. At this point in time, Nansen was not sure whether they really were on an offshore island of Franz Josef Land. It was not until August 16 that he identified a headland as Cape Fields , which was to be found on the Julius von Payers map on the west coast of Franz Josef Land. The goal was now to reach the so-called Eira Harbor at the southwestern end of the archipelago and there a hut with supplies that had been built by the British Arctic Expedition (1881-1882) under Benjamin Leigh Smith . However, changing winds and drifting ice endangered the onward journey in the kayaks, which is why Nansen decided on August 28, due to the approaching polar winter, to set up winter camp on the southwest coast of the island later known as Jackson Island and wait there until the coming spring. Their stay in a makeshift quarter lasted eight months.

On May 19, 1896, Nansen and Johansen continued on their way. For more than two weeks they followed the coastline southwards. Again, none of the landmarks seemed to match your map of Franz Josef Land. Thanks to a change in the weather on June 4th, they were able to continue their way in the kayaks for the first time since leaving winter camp. On June 17, Nansen and Johansen met Frederick George Jackson , who was on his own expedition to Franz Josef Land and had set up his headquarters at Cape Flora on Northbrook Island , the southernmost land mass of the archipelago. There, Nansen and Johansen waited for the next few weeks for Jackson's supply ship Windward , which arrived at Cape Flora on July 26th . On August 7th, the Windward sailed for Norway with Nansen and Johansen on board. Vardø was reached on August 13, 1896, and Nansen sent numerous telegrams informing him of his safe return. In Tromsø on August 21, 1896 there was an exuberant reunion between Nansen, Johansen and the other expedition members who had arrived in Norway with the Fram .

After Nansen and Johansen started their march in March 1895, the rest of the crew, led by Otto Sverdrup, continued the drift with the Fram . This lasted until August 13, 1896, when the ship had entered the open water northwest of Spitsbergen. Nansen's original assumption about the direction of the ice drift was thus confirmed. The ship first called at Svalbard. Nothing was known about the whereabouts of Nansen and Johansen at the time. After a short stay in the country, the team returned to Norway with the Fram .

Results and aftermath of the expedition

Upon arrival in Christiania on September 9, 1896, a squadron of warships escorted the Fram into the harbor, where, according to Roland Huntford, the greatest crowd the city had ever seen cheered the crew frenetically. Congratulations came from all over the world. For example, the British mountaineer Edward Whymper wrote that Nansen's expedition "achieved almost the same progress as all other research expeditions of the 19th century put together."

Nansen's first task after the expedition returned was to publish a travel report. In November 1896 the Norwegian version of his book Fram over Polhavet was ready, which appeared in 1897 under the title In Nacht und Eis as a German-language edition and in English under the title Farthest North . He wasn't afraid to let critics have their say. The book contained a comment by Adolphus Greely , uncommented by Nansen and published in advance in Harper's Weekly magazine , who sharply criticized Nansen's alleged breach of duty for leaving the other expedition members hundreds of kilometers from safe land to their fate on their own when leaving the Fram . Despite this criticism, the book's publication was a great success and made Nansen financially independent. As after the Greenland expedition, Nansen received numerous awards from home and abroad after this trip. King Oscar II awarded him and Otto Sverdrup the Grand Cross of the Saint Olav Order in September 1896 . During a lecture tour through Europe in the spring of 1897, the Société de Géographie honored him with the Society's gold medal and the French President Félix Faure elevated him to the rank of Commander of the Legion of Honor . In Russia awarded him Tsar Nicholas II. With the Order of Saint Stanislaus (1st class) and in Germany awarded him the Geographical Society also a gold medal, the Alexander von Humboldt medal . The Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I presented him with the Grand Cross of the Franz Joseph Order and in England and in October 1897 at lectures in the United States , Nansen received awards and honors. He was also made an honorary member of numerous academies and societies, including the Norwegian Academy of Sciences , the Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and the Royal Geographical Society . From 1896 he was also a member of the Leopoldina Scholars' Academy .

Although Nansen missed the main goal of reaching the geographic North Pole for the first time, the expedition provided significant geographic and general scientific discoveries. The meteorological and oceanographic observations carried out during the ice drift of the Fram contributed in particular to this . Nansen's observations made it clear for the first time that there are many more animal species in the ice deserts than originally assumed. Henrik Mohn's theory of transpolar drift flow had been confirmed. In addition, the data collected provided evidence for the first time that the North Pole is neither on land nor on a permanent ice sheet, but in the middle of a zone of moving pack ice. The Arctic Ocean has been shown to be a deep-sea basin with no significant land masses north of the Eurasian continent, as these would otherwise have hindered the observed ice drift. A century after that expedition, the British polar explorer Wally Herbert described the Fram's voyage as "one of the most inspiring examples of daring cleverness in the history of exploration."

Academic career

Professorship and further research trips

During the following 20 years, Nansen devoted himself primarily to his work as a scientist. In 1897 he was appointed professor of zoology at the University of Christiania. This gave him sufficient opportunity to analyze and publish the scientific data of the Fram expedition. This became a far more arduous task for him than writing his book. The results comprised six volumes and, according to the later description of the polar explorer Robert Neal Rudmose-Brown (1879–1957) meant "for the oceanography of the Arctic what the results of the Challenger expedition mean for the oceanography of the other seas." In 1900 Nansen took part in a research trip to the waters around Iceland and Jan Mayen , which was led by Johan Hjort (1869-1948), the director of the Norwegian Marine Research Institute in Bergen. The research ship Michael Sars used for the expedition was named after Nansen's father-in-law. Shortly after his return from this trip, Nansen learned that his northern record was set at 86 ° 13.6 ′ N on April 8, 1895 by a group of three around the Italian polar explorer Umberto Cagni on April 24, 1900 in an attempt to find the North Pole by Franz-Josef - Land from reach, at 86 ° 34 ′ N had been broken. His reaction was sober: “What use are achieved goals just for their own sake? They're all disappearing ... it's just a matter of time. ”In 1902, Nansen helped found the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), based in Copenhagen, and took over the management of the ICES oceanographic laboratory, the International Central Laboratory in Christiania.

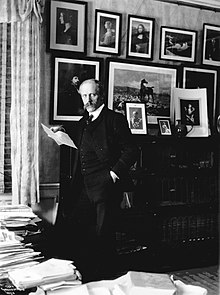

After the birth of their daughters Liv and Irmelin and their two sons Kåre and Odd between 1893 and 1901, the house that Nansen built in 1891 from the proceeds of his book on the Greenland expedition became too small for his family. He bought a plot of land in the west of Christiania and had an imposing mansion built there based on his own designs with elements of the Renaissance style, in the basement of which he set up a mechanical workshop for building scientific instruments. In April 1902, the Polhøgda estate (German: The polar heights ) was ready for occupancy and it remained Nansen's home until his death. Nansen's youngest son Asmund was born there in 1903.

Nansen's research focus had meanwhile shifted to the field of oceanography. In 1905 he made the oceanographic data collected during the Fram expedition available to the Swedish physicist Vagn Walfrid Ekman . Ekman recognized from the drift direction of the Fram that the ocean current deviated from the prevailing wind direction in a characteristic way, which he called " corkscrew current" and which is related to the Coriolis force caused by the rotation of the earth . Through his own experiments, Ekman also deepened Nansen's findings on dead water , a form of internal waves that occur at the horizontal boundary between water layers of different densities.

On May 1, 1908, Nansen gave up teaching zoology and became professor of oceanography. In 1909, together with Bjørn Helland-Hansen, he published a paper in which, among other things, he evaluated the results of the research trip with Michael Sars nine years earlier. Between 1910 and 1914 he took part in some oceanographic expeditions. In 1910 he took a trip with the gunboat Frithjof to the North Atlantic. In 1912 he went on board his own yacht Veslemøy to Bear Island and to Svalbard to carry out investigations into the currents and salinity of the sea water at various depths. For this purpose, Nansen had already developed a special sampling container around 1910, which later became known as the Nansen bottle and was generally used as a standard instrument until the 1980s - from 1966 in a variant modified by the American Shale Niskin (1926–1988). Immediately before the outbreak of the First World War , he accompanied Helland-Hansen on a trip to the north-eastern Atlantic.

The year 1913 was marked by two strokes of fate for Nansen: in January his old companion Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen committed suicide and in March his youngest son Asmund died after a long illness. In the summer, Nansen took part in a trip to the Kara Sea as a member of a delegation to explore new trade routes from Western Europe to Siberia . This led him along the Yenisei to Krasnoyarsk , in order to then advance with the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok . Incidentally, he provided evidence that the West Siberian lowlands were previously glaciated. During this trip, Nansen's sympathy for the Russian people developed, which had a lasting impact on his later political life.

Leading figure in polar research

Nansen was stylized into a living legend. All prospective explorers to the Arctic and Antarctic sought his advice in the years following the Fram expedition. Among them were Adrien de Gerlache de Gomery in June 1897 , who survived the first winter in Antarctica during his Belgica expedition (1897–1899), and in January 1899 the Duke of Abruzzo and his colleague Umberto Cagni a little more than a year later, Nansens The northern record broke, as did the German polar explorer Erich von Drygalski in September 1899, who explored and mapped the Kaiser Wilhelm II land in Antarctica as part of the Gauss expedition (1901–1903) . On the other hand, Nansen refused to give his compatriot Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink any support because he considered him a fraud. Even Ernest Shackleton and Robert Falcon Scott was Nansen advice. Nansen's vigorous efforts to get both expedition leaders to use sled dogs as the main draft animals, however, were unsuccessful. According to some historians, this negative attitude prevented Shackleton from being the first person to reach the South Pole during the Nimrod Expedition (1907–1909) and cost Scott his life on the Terra Nova Expedition (1910–1913).

Nansen had considered a South Pole expedition and had already commissioned Colin Archer to draw up plans for two new expedition ships. Ultimately, none of this was actually put into practice for a variety of reasons. So he left Roald Amundsen the Fram for his research trip, originally planned as a North Pole expedition. However, Amundsen secretly changed his plans after Frederick Cook had asserted his claim to the conquest of the North Pole, and undertook with his Antarctic expedition (1910-1912) in the competition against Robert Falcon Scott the "attack" on the South Pole. Nansen defended this controversial decision, but was not privy to it.

Commissioned by the Royal Geographical Society, he wrote a two-volume work on the history of the northern expeditions, which appeared in 1911 under the title In Northern Mists . During this time, the now widowed Nansen was said to have had a brief affair with Kathleen Scott . His last connection to polar research was the International Study Society for Exploring the Arctic with Aircraft ( Aeroarctic ), founded on the initiative of Walther Bruns , which Nansen elected on October 7, 1924 as president for life and scientific director of a planned polar expedition by airship. The Arctic voyage of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin , for which he was emphatically committed, did not take place until 1931, a year after Nansen's death.

Political career

Norwegian independence advocate

The Swedish-Norwegian personal union, which has existed since 1814, has been hotly contested in Norway since the 1890s at the latest, despite the peaceful coexistence of both countries in the wake of burgeoning nationalist currents and the desire for political independence. Although Nansen was not aiming for a career in politics at the time, he was still aggressively advocating Norwegian interests at every opportunity that presented himself. After an agreement between the two countries had initially emerged, all negotiations on Norway's future status were broken off in February 1905. The incumbent Norwegian government under Prime Minister Francis Hagerup then resigned. The policy of his successor Christian Michelsen was aimed at the complete separation of Norway from Sweden. Nansen had openly acknowledged the separation movement of the new government in a few newspaper articles, but turned down Michelsen's offer to take up a ministerial office in his cabinet. At Michelsen's request, Nansen went to London, where he affirmed in an article in the Times that his country should be represented internationally by its own consulates in the future. In addition, the publication of his book Norway and the Union with Sweden (in the original: Norge og foreningen med Sverige ) should promote the discussion about Norway's political independence, especially abroad. On May 17, 1905, the Norwegian national holiday, Nansen said during a passionate speech to a large crowd in Christiania: “Now all routes of retreat are blocked. Now there is only one way, the way forward, possibly associated with difficulties and hardships, but forward for our country, for a free Norway. "

The political situation came to a head in the early summer of 1905. Oscar II refused to consent to the entry into force of a law passed by Storting on the independent diplomatic representation of Norway abroad. Nor did he accept the subsequent resignation of the Norwegian government. Thereupon the Norwegian parliament declared the personal union over on June 7th. The Swedish side was ready to have the Norwegian question answered in the form of a referendum . In the vote held on August 13, 99.5% of Norwegians were in favor of separating from Sweden. Oscar II then abdicated as the Norwegian king. In a second referendum in November 1905, the Norwegians voted to keep the monarchy . Shortly afterwards, Nansen traveled on a secret mission to Copenhagen and was able to persuade Carl von Glücksburg, Prince of Denmark , to accept the Norwegian crown. After the joint coronation with his wife Maud on June 22, 1906 in Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim , he became the first king of independent Norway as Haakon VII.

In April 1906 Nansen took over the post of Ambassador of Norway in London. His main task was to negotiate an agreement with the other European representatives to guarantee the continued existence of Norway's sovereignty . Nansen enjoyed great popularity in England and was on friendly terms with King Edward VII , who on November 13, 1906, honored him as the Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order at St James's Palace . On the other hand, the customs at the English court and his official duties were repugnant to him. He himself called it "shameless and boring". However, his position allowed him to pursue his scientific interests through contacts with the Royal Geographical Society and other scholars. After the treaty was signed on November 2, 1907, Nansen resigned from the office of ambassador on November 15, contrary to the requests of King Edward and other notables . A short time later, Nansen, as the king's guest at Sandringham Castle, received news that his wife Eva had developed severe pneumonia . On December 8th, Nansen returned to Norway, but learned of her death before arriving at Polhøgda .

Humanitarian achievements as a diplomat

When the First World War broke out, Norway, along with Sweden and Denmark, declared neutrality. Nansen was appointed president of the largely insignificant Nordic Defense Union, which brought few obligations with it, so that he could devote himself mainly to his scientific activities. In the further course of the war the situation in Norway became threatening due to the blockade of important international trade routes. The situation worsened after the USA entered the war in 1917. As a special envoy, after months of negotiations in Washington , Nansen managed to get the USA to deliver grain and other supplies to Norway, thus averting an impending famine. In doing so, he ignored his government, which hesitated when signing the contract in view of the required consideration in the form of rationing measures.

A few months after the end of the war, during the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, based on the 14-point program of US President Woodrow Wilson, a provisional agreement was reached to establish the League of Nations in order to be able to settle future international disputes by peaceful means. Through Nansen's initiative, Norway became a full member and one of thirteen permanent members of the Executive Committee in 1920. He himself headed the Norwegian delegation. In the same year he took care of the return of war refugees and prisoners worldwide on behalf of the League of Nations. As Nansen the League of Nations was able to announce the successful return shipments of 200,000 returning soldiers in November 1920 he wrote: "Never in my life before I came across such a powerful suffering." By the year 1922 saw Nansen in particular by the introduction of the Nansen passport for the homecoming of a total of 427,886 people from around 30 countries. Well-known holders of this pass included Marc Chagall , Igor Stravinsky , Aristotle Onassis , Rudolf Nureyev and Anna Pavlova . In recognition of his work, the responsible committee of the League of Nations wrote that Nansen's achievements "contain stories of heroic endeavors worthy of those of his crossing of Greenland or the great Arctic voyage."

Before the end of his engagement, he was appointed the League of Nations' first high commissioner for refugee issues through the mediation of Philip Noel-Baker . In this role, Nansen tried to resettle about two million refugees from the Russian Revolution (1917) and the subsequent civil war (1917–1920) . His work was made more difficult by the famine that hit the country in 1921 after a series of mistakes. Since the League of Nations mistrusted the government of Soviet Russia despite Nansen's plea for hunger relief, it was primarily dependent on donations from private organizations. At the request of the International Red Cross , he opened an office in Moscow for relief operations, which, however, were only able to contain the famine to a limited extent. In bitterness, he noted:

“In many countries on both sides of the Atlantic there was such an abundance of corn that the farmers were forced to burn it in the cauldrons of the railways. At the same time ships were lying idle in Europe because there was no cargo, [and] thousands, no millions, were unemployed. All of this while 30 million people in the Volga region, not far away and easily accessible by our ships, were left to starve and die. "

After the end of the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) Nansen traveled to Constantinople to negotiate the return of the mostly Greek refugees. These negotiations led to the forced relocation of hundreds of thousands of Turks and Greeks to their respective home countries, which is still controversial today and which lasted for several years. In November 1922, during a conference in Lausanne , Nansen learned that he had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, which he received on December 10, 1922 “[for] his work on the return of prisoners of war, his work for the Russian refugees, his efforts to help millions from hunger threatened Russians and finally his current work for refugees in Asia Minor and Thrace ”. He donated the entire prize money to refugee aid.

From 1925 Nansen became involved in the Armenian people who were affected by the genocide by the Ottoman Empire during the First World War , and who were de facto stateless due to the incorporation of their territory into the Soviet Union. Nansen, supported by the later Nazi collaborator Vidkun Quisling , strove for the statehood of the Armenians on the territory of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic . 15,000 Armenians were to be settled here on 360 km². The plan, which is conceptually considered to pave the way for the Marshall Plan after World War II , failed because insufficient funds were raised. Regardless of this, Nansen is still highly regarded by the Armenians today.

Aside from the refugee issues, Nansen took a stand on various issues in the League of Nations. He believed that the international organization, especially for the smaller states like Norway, "is a unique opportunity to speak in the councils of the world," and that the credibility of the League of Nations was measured by the extent of disarmament . Nansen was one of the signatories of the slavery agreement of September 25, 1926. In addition, he campaigned for the suspension of German reparations payments and for Germany's admission to the League of Nations.

Late years of life and death

On January 17, 1919, Nansen married Sigrun Munthe (1869–1957), with whom he is said to have had an affair as early as 1905 when he was married to his first wife Eva. This marriage was resented by his children and was also unhappy. As is apparent from the publication of love letters in 2011, Nansen had a relationship with the much younger American author Brenda Ueland (1891-1985) during his second marriage.

He largely avoided meddling in Norwegian domestic politics. In 1924, however, the former Prime Minister Christian Michelsen won him over to put his good name in the service of founding the anti-communist organization Fedrelandslaget in order to counter the increasing influence of the then Marxist- oriented workers' party. At a Fedrelandslaget event in the Norwegian capital, Nansen said: "To speak about the right to revolution in a society of civil liberty, unrestricted suffrage and equal treatment for everyone [...] really sounds like idiotic nonsense."

In 1925, as the successor to Rudyard Kipling and the first foreigner , Nansen was given the honor of being elected Lord Rector of the University of St Andrews for three years . He used his inaugural speech for a philosophical review of his life and a pathetic appeal to future generations: “We are all looking for the land of promise in our lives - [...] It is up to us to find the way there. A long, possibly hard way. [...] depth in addition rooted in our being the spirit of adventure, the call of the wilderness that resonates in all our actions and our lives deeper, richer and makes noble. "In the same year he was awarded King Haakon VII. Borgerdådsmedalje time highest civil honor in Norway, the Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Olav with an order chain . He later bequeathed these and all other awards that Nansen had received in the course of his life in the form of orders and medals to the Coin Cabinet of the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo.

His obligations for the League of Nations hardly allowed him to stay in Norway. Although his scientific activities suffered, he occasionally presented the results of his work to the public. He toyed with the idea of a flight to the North Pole, but couldn't find enough money for it. Finally, Roald Amundsen got ahead of him , who reached the North Pole on May 12, 1926 in the airship Norge together with Umberto Nobile and other expedition members . Two years later, Nansen gave a commemorative address on the radio for his compatriot, who had died on a rescue flight for the distressed Nobile, in which he said: “He has found an unknown grave under the clear sky of the icy world, with the Wings of eternity [...]. "

As long as his numerous obligations allowed, Nansen went on a skiing holiday in winter. In February 1930 two of his friends noticed during a joint stay in the mountains near Geilo that the now 68-year-old was suffering from early signs of fatigue . Upon returning to Lysaker, the doctors diagnosed the flu , which was later accompanied by phlebitis , which confined him to bed for the last few weeks of his life. Finally, Nansen died of a heart attack on May 13, 1930, sitting in a deck chair on the balcony above the south terrace of his Polhøgda house with a view of the Oslofjord .

Before the cremation, Nansen's coffin was laid out in the pillar portal of the University of Oslo as part of a state act on May 17, 1930. Only in the spring of 1937, the Ministry of Church and Education gave the family permission to the testamentary comply possessed desire Fridtjof Nansen, the urn in the garden of his estate Polhøgda bury. His daughter Liv remembered that there were no funeral orations at the ceremony, only Schubert's string quartet Death and the Maiden , which had been part of the repertoire of Nansen's wife Eva. Among the numerous expressions of honor was that of the British League of Nations President Lord Robert Cecil , who particularly recalled Nansen's tireless work for the international organization: “Every good cause found support. He was a fearless peacemaker, a friend of justice, a constant advocate for the weak and the suffering. "

Aftermath and honors

Nansen's achievements were pioneering in a wide variety of disciplines. At a young age, he was directly involved in modernizing skiing into a widespread sport. He used the knowledge he gained for his expeditions, thereby revolutionizing the techniques of polar travel. To him the development of the eponymous goes Nansen carriage and later by the company Primus advanced cooker back. In addition, Nansen is considered to be the inventor of multi-layered functional clothing based on the onion skin principle , which replaced the cumbersome woolen clothing traditionally used on polar journeys. In the natural sciences he is regarded as one of the fathers of modern neurology and as a pioneer of the then still young oceanography.

During his time as the League of Nations High Commissioner for Refugee Issues, he laid the foundations for an internationally recognized legal status for refugees. Immediately after his death, the International Bureau for Refugees named after him was founded to continue his work. Significant achievements of this organization were the ratification of a refugee agreement recognized by 14 states in 1933, the resettlement of 10,000 Armenians in the city of Yerevan and the admission of a further 40,000 people of this ethnic group through Syria and Lebanon . Although the office failed miserably in the accommodation of refugees from Nazi Germany and the Spanish Civil War due to questions of jurisdiction and resistance from potential host countries, it was also awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1938, 16 years after Nansen, but it was not prevented the dissolution of the organization a short time later. The United Nations, which was founded in 1945 as the successor organization to the League of Nations, has awarded the Nansen Refugee Prize, initially known as the Nansen Medal , every year since 1954 . The endowed award is given by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to individuals or groups “in order to honor their extraordinary dedication to refugee protection”.

Nansen's portrait is shown in the fourth and fifth series of banknotes issued by the Norwegian Central Bank on the front of the 5-kroner (1955 to 1963) or 10-kroner note (1972 to 1984), valid until July 13, 1999.

The German Chancellor Willy Brandt quoted Nansen in his acceptance speech on the occasion of the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to him on December 10, 1971:

“We are here in Fridtjof Nansen's country. His warning also applies in a figurative sense: "Fort dere - før det he for sent å angre": Hurry up to act before it is too late to repent. "

Streets, squares, schools, sports clubs and other organizations at home and abroad bear Nansen's name. The Polhøgda estate has been the seat of the Fridtjof Nansen Institute since 1958 , which deals with global environmental issues and those relating to energy and resource consumption. In addition, a number of geographical objects were named after him. They include:

- Mount Nansen ( 62 ° 6 ′ N , 137 ° 18 ′ W ) in the Yukon Territory of Canada ,

- Mount Nansen ( 74 ° 33 ′ S , 162 ° 36 ′ E ) and the Nansen ice table ( 74 ° 53 ′ S , 163 ° 10 ′ E ) in the Antarctic Victoria Land ,

- Mount Fridtjof Nansen ( 85 ° 21 ′ S , 167 ° 33 ′ W ) in the Queen Maud Mountains of Antarctica,

- the Nansen mountain ( Russian Гора Нансена , transkr .: Gora Nansena; 74 ° 40 ′ N , 56 ° 21 ′ E ) on Novaya Zemlya ,

- Pik Nansen ( 42 ° 9 ′ N , 79 ° 38 ′ E ) in the Tian Shan Mountains in eastern Kyrgyzstan

- the Nansen Island ( 64 ° 35 ' S , 62 ° 6' W ) on the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula ,

- which the Taimyr peninsula upstream Nansen Island ( Russian Остров Нансена , transk .: Ostrow Nansena; 76 ° 12 ' N , 94 ° 45' O ),

- to Franz Josef Land associated Nansen Island ( Russian Остров Нансена , transk .: Ostrow Nansena; 80 ° 30 ' N , 54 ° 13' O ),

- the chapter Nansen ( 72 ° 9 ' N , 104 ° 57' W ) on the east coast of North Canadian Victoria Island ,

- the chapter Nansen ( 68 ° 13 ' N , 29 ° 25' W ) on the east coast of Greenland

- the chapter Nansen ( 79 ° 11 ' N , 17 ° 46' W ), the largest of the North Cape Norske Øer in the Northeast Greenland National Park ,

- the chapter Nansen ( Russian Мыс Нансена , transk .: Mys Nansena; 80 ° 28 ' N , 47 ° 26' O ) to the east coast of Prince George's country in the archipelago Franz Josef Land,

- the Nansen Nunataks ( 81 ° 23 ′ N , 33 ° 45 ′ W ) in North Greenland,

- the Nansen Sound ( 81 ° 0 ′ N , 90 ° 35 ′ W ), a waterway between Ellesmere Island and Axel Heiberg Island ,

- the Nansen Basin ( 84 ° 30 ′ N , 75 ° 0 ′ E ) in the Greenland Sea ,

- the Nansen-Gakkel Ridge ( 84 ° 30 ′ N , 5 ° 0 ′ E ) in the Arctic Ocean ,

- the Nansen Glacier ( Norwegian Nansenbreen ; 78 ° 23 ' N , 13 ° 54' O ) and the Nansen pass ( Norwegian Nansenpasset ; 78 ° 26 ' N , 13 ° 40' O ) on the island of Spitsbergen ,

- the Fridtjof-Nansen-Land , the 1932/33 Norwegian-occupied area in south-east Greenland

- and probably also the Fridtjof Island ( 64 ° 35 ′ S , 63 ° 21 ′ W ) in the Antarctic Palmer Archipelago .

The name of the asteroid (853) Nansenia is also derived from Fridtjof Nansen.

Several ships are or were named after him, including the Norwegian coast guard and fisheries protection ship Fridtjof Nansen , the Norwegian research ship Dr. Fridtjof Nansen , the German mainsail schooner Fridtjof Nansen and the first of five Norwegian frigates of the Fridtjof Nansen class , the KNM Fridtjof Nansen (F310) .

The Norwegian government under Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg officially declared 2011, which marked the 150th anniversary of Nansen's birthday and the 100th anniversary of Roald Amundsen's first reaching of the South Pole, the “Nansen Amundsen Year”. The life and work of both polar explorers were remembered with numerous events and exhibitions.

Literature cited

Nansen biographies

- WC Brögger, Nordahl Rolfson: Fridtjof Nansen 1861–1893 . Longmans, Green & Co., London, New York & Bombay 1896 ( online at Internet Archive [accessed October 5, 2011]).

- Eugen von Enzberg: Nansen's successes . Fußinger's bookstore, Berlin 1897.

- Roland Huntford : Nansen . Abacus, London 2001, ISBN 0-349-11492-7 .

- Ernest Edwin Reynolds: Nansen . Geoffrey Bles, London 1932.

- JM Scott: Fridtjof Nansen . Heron Books, Sheridan 1971.

- Jon Sørensen: Fridtjof Nansen's saga . Jacob Dybward Forlag, Oslo 1931.

- Stefan Wack: Fridtjof Nansen as a neurohistologist. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 9, 1991, pp. 363-376.

Expedition reports

- Roald Amundsen : The South Pole . Vol. II. John Murray, London 1912 ( Online in Internet Archive [accessed November 15, 2010]).

- Pierre Berton : The Arctic Grail . Viking Penguin, New York 1988, ISBN 0-670-82491-7 .

- Wally Herbert : The Noose of Laurels . Hodder & Stoughton, London 1989, ISBN 0-340-41276-3 .

- Fergus Fleming: Ninety Degrees North . Granta Publications, London 2002, ISBN 1-86207-535-2 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed November 24, 2011]).

- Fridtjof Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . Longmans, Green & Co., London, New York, Bombay, Calcutta & Madras 1919 ( online at Internet Archive [accessed October 5, 2011]).

- Fridtjof Nansen: In night and ice . Volumes I and II. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1897 ( Volumes I and II online in the Internet Archive [accessed on January 24, 2012]).

- Diana Preston: A First Rate Tragedy . Constable & Co., London 1997, ISBN 0-09-479530-4 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed November 24, 2011]).

- Beau Riffenburgh: Nimrod . Bloomsbury Publications, London 2005, ISBN 0-7475-7253-4 .

Others

- Otto Arnold Delphin Amundsen: The Kongelige norske Sankt Olavs Orden, 1847-1947 . Grøndahl & Søns, Oslo 1947.

- Kenneth J. Bertrand, Fred G. Alberts: Geographic Names of Antarctica . US Govt. Print. Off., Washington 1956 ( online at Internet Archive [accessed October 5, 2011]).

- Karen E. Cullen: Marine Science . Chelsea House, New York 2006, ISBN 0-8160-5465-7 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed February 9, 2012]).

- Heinz Duchhardt (Hrsg.): Yearbook for European history . tape 5 . Oldenbourg, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-486-56841-8 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed on January 21, 2012]).

- Roland Huntford: Two Planks and a Passion: The Dramatic History of Skiing . Continuum International Publishing, London 2008, ISBN 978-1-4411-3401-1 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed February 9, 2012]).

- Frederick Pollok: The League of Nations . Clark, New Jersey 2003, ISBN 978-1-58477-247-7 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Fridtjof Nansen in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Fridtjof Nansen in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Fridtjof Nansen in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Works by Fridtjof Nansen in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Fridtjof Nansen in the Internet Archive

- Literature list from the Fridtjof Nansen Institute

- Fridtjof Nansen , Norwegian National Library photo collection on flickr.com

- Sebastian Kirschner: Fridtjof Nansen - polar researcher, zoologist, diplomat Bavaria 2 radio knowledge . Broadcast on January 9, 2020 (podcast)

Individual evidence

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen - The Nobel Peace Prize 1922. Information on the website of the Norwegian Nobel Institute (English). Retrieved April 15, 2020

- ^ Brögger and Rolfsen: Fridtjof Nansen 1861–1893. 1896, p. 1.

- ^ Duchhardt: Yearbook for European History, Volume 5. 2004, p. 58.

- ^ Brögger and Rolfsen: Fridtjof Nansen 1861–1893. 1896, pp. 10-13.

- ↑ Baldur Nansen , photo (approx. 1884) on the website of the Norwegian National Library. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ Adelaide Nansen , photo (approx. 1873) on the website of the Norwegian National Library. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ↑ Store Frøen , Photo (ca. 1871) on the website of the Norwegian National Library. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen. P. 8.

- ↑ Alexander Nansen , photo (approx. 1895) on the website of the Norwegian National Library. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ Brögger and Rolfsen: Fridtjof Nansen 1861–1893 . 1896, pp. 8-9.

- ^ Family Nansen , photo (approx. 1866) on the website of the Norwegian National Library. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ↑ a b Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 11-14.

- ^ A b c Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 7-12.

- ↑ Scott: Fridtjof Nansen . 1971, pp. 9-10: “ like Robinson Crusoe ”

- ↑ Fridtjof Nansen , short biography on the website of the Committee for the Award of the Nobel Peace Prize. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Huntford: Two Planks and a Passion. 2008, p. 131.

- ^ Sørensen: Fridtjof Nansen's saga. 1931, p. 22.

- ^ Irwin Abrams: The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates: An Illustrated Biographical History, 1901-2001. Watson Publishing, Nantucket 2001, ISBN 978-0-88135-388-4 , p. 102. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ^ Cullen: Marine Science. 2006, p. 16.

- ↑ Egil Sakshaug, Geir Johnson, Kit Kovacs (ed.): Ecosystem Barents Sea. Tapir Academic Press, Trondheim 2009, ISBN 978-82-519-2461-0 , p. 28 . Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d e Linn Ryne: Fridtjof Nansen , Norwegian Foreign Ministry. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Von Enzberg: Nansen's successes . 1897, pp. 10-11.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ a b Scott: Fridtjof Nansen . 1971, p. 15: “ the first fatal step that led me astray from the quiet life of science. ”

- ^ A b c Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 21-27.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, p. 20.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen. 2001, p. 25.

- ↑ Fridtjof Nansen , short biography on Norwegian Language Blog. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, p. 25.

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen: Bidrag til Myzostomernes Anatomi og Histologi (German: contributions to the anatomy and histology of myzostomerns ). John Grieg, Bergen 1885. Online version from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 56.

- ↑ Michael von Lenhossék : The finer structure of the nervous system in the light of the latest research. Berlin 1895, p. 210 f.

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen: Preliminary Communication on some Investigations upon the Histological Structure of the Central Nervous System in the Ascidia and in Myxine glutinosa. In: The Annals and the Magazine of Natural History , Vol. XVIII (5th series). 1886, p. 225. Retrieved October 5, 2011: “ Anastomoses or unions between the different ganglion cells ”

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen: The structure and combination of the histological elements of the central nervous system . John Grieg, Bergen 1887. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 65-69.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 73-75.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 2001, pp. 44-45.

- ↑ Scott: Fridtjof Nansen . 1971, pp. 44-46.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. 3 : “ For if they were to start […] from the west side, they were practically certain never to get across. They would have all the flesh pots of Egypt behind them, and in front the unexplored desert of ice [...]. ”

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 79-81.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. 4

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. 8 : “ […] if Nansen's scheme be attempted in its present form, […] the chances are ten to one that he will either uselessly throw his own and perhaps others' lives away […]. ”

- ^ Peter Eberlin: Frithjof Nansen's plan at løbe paa Ski tværs over Grønland. In: Ny Jord 1, 1888, ( Memento from December 23, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) p. 186 ff.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. Vii.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. 9.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 78.

- ^ Samuel Johannesen Balto , short biography on the website of the Fram Museum. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ↑ Ole Nilsen Ravna ( Memento from December 12, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), short biography on the Fram Museum website.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, pp. 18-20.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. 14.

- ↑ Kristian Kristiansen ( Memento from December 12, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), short biography on the Fram Museum website.

- ↑ Oluf Dietrichson ( Memento from December 12, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), short biography on the Fram Museum website.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, pp. 12-18.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 87-92.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 97-99.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 97–99: “ in good spirits and with the highest hopes of a fortunate result ”

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 48-52.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 105-110.

- ↑ Scott: Fridtjof Nansen . 1971, p. 84.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 115-116.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. 447.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. 250.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. 270 : “ […] hailed my change of plan with acclamation. ”

- ↑ These values are only extrapolated, however, since the thermometers carried with them could not show any values below -37 ° C and the aneroid barometer could not show any heights above 2,400 m (Walter Ambach: 100 years ago: On snowshoes through Greenland, turning point in exploration of the Greenland Ice Sheet In: Polarforschung 58 (1), 1988, pp. 53-55; PDF file, 180 KB).

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 61-62.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 64-67.

- ↑ a b Barry Wyke: Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930). A note on his contribution to neurology on the occasion of the century of his birth. In: Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Volume 30, April 1962, pp. 243-252, PMID 14038096 , PMC 2414154 (free full text). Supplement: According Wyke Nansen later also the title of Doctor of Science were (Engl. Doctor of Sciences and a legal doctoral degree (Engl., D.Sc.) Doctor of Civil Law , DCL) awarded.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. 363 : “ could have been more remote from my thought at the moment. ”

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 69-70.

- ↑ Fridtjof Nansen: Eskimo life . Globus, Berlin 1920. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. 444 : “ It was not without sorrow that most of us left this place and these people, among whom we had enjoyed ourselves so well. ”

- ^ Nansen: The first crossing of Greenland . 1919, p. 446.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 157.

- ^ A b Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 156-163.

- ^ Huntford: Two Planks and a Passion. 2008, p. 141.

- ↑ a b Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 71-72.

- ↑ Brögger and Rolfson: Fridtiof Nansen, 1861-1893 . 1896, p. 292.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 156.

- ↑ Meeting of June 1, 1889 . In: Negotiations of the Society for Geography in Berlin. 16, 1889, p. 254 .

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 179.

- ^ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North . 2002, p. 238.

- ^ A b Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 168-173.

- ↑ Tor Borch Sannes: The Fram. Adventure polar expedition , Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1987, ISBN 3-455-08252-1 , p. 37.

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen , genealogical information on Finn Holbek's website. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ↑ Thomas O. Hiscott: Henry G. Bryant and the Role of the Geographical Society In Tum-of-the-Century Arctic Exploration ( Memento of the original from July 5, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Haverford College May 2002, p. 31. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ↑ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume I. 1897, pp. 32–43.

- ^ Berton: The Arctic Grail . 1988, p. 489.

- ^ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume I. 1897, pp. 23-27.

- ^ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume I. 1897, pp. 44-47.

- ^ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume I. 1897, p. 50.

- ↑ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume I. 1897, pp. 65-67.

- ↑ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume I. 1897, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 234-237.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 238–239: “ Well and truly moored for the winter. ”

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 242.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 246.

- ^ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume I. 1897, p. 310.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 257-258.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 268-269.

- ^ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume II. 1897, p. 35.

- ^ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North . 2002, p. 248.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 320: “ My fingers are all destroyed. All mittens are frozen stiff… It is becoming worse and worse… God knows what will happen to us. ”

- ^ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume II. 1897, p. 62.

- ↑ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume II. 1897, p. 63.

- ^ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume II. 1897, p. 176.

- ^ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume II. 1897, pp. 187–191.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 373.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 375-379.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 403-404.

- ^ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North . 2002, pp. 261-262.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 433-434.

- ^ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North . 2002, pp. 264-265.

- ^ A b Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 423-428.

- ^ Berton: The Arctic Grail . 1988, p. 498.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 438.

- ^ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North . 2002, pp. 264–265: “ almost as great an advance as has been accomplished by all other voyages in the nineteenth century put together. ”

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I and Vol. II . Harper & Bros., New York & London 1897. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume I. 1897, p. 41.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 441-442.

- ↑ Huntford, Nansen . 2001, p. 445.

- ↑ Huntford, Nansen . 2001, pp. 449 and 480.

- ^ Société de Géographie: Reception du Dr Fridtjof Nansen . Comptes rendus des séances 1897, No. 8, p. 124 and p. 136. Norwegian National Library. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ↑ Huntford, Nansen . 2001, p. 461.

- ↑ Huntford, Nansen . 2001, p. 449.

- ↑ Meeting of January 8, 1898 . In: Negotiations of the Society for Geography in Berlin . 25, 1898, p. 55 .

- ↑ a b Amundsen: Den Kongelige norske Sankt Olavs Orden, 1847–1947. 1947, p. 13.

- ↑ Huntford, Nansen . 2001, p. 452.

- ^ Nansen, In Nacht und Eis , Volume II. 1897, pp. 485-490.

- ^ Herbert: The Noose of Laurels . 1989, p. 13: “ one of the most inspiring examples of courageous intelligence in the history of exploration. ”

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 452.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 159-160: “ were to Arctic oceanography what the Challenger expedition results had been to the oceanography of other oceans. ”

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 468: “ What is the value of having goals for their own sake? They all vanish ... it is merely a question of time. ”

- ↑ a b Cecilie Mauritzen: The science of the sea. In: Olav Christensen (editor): Nord! Fridtjof Nansen's legacy. Science in the Far North ( Memento from October 29, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) , PDF file (3.7 MB). Fram Museum / University of Oslo, 2011, ISBN 978-82-8235-054-9 , p. 60.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 177-178.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 477-478.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 555-556.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 476.

- ↑ Nansen: In Nacht und Eis , Volume I. 1897, pp. 147-148.

- ↑ John Grue: Underwater waves in the sea. In: Olav Christensen (editor): Nord! Fridtjof Nansen's legacy. Science in the far north. Fram Museum / University of Oslo, 2011, ISBN 978-82-8235-054-9 , p. 72 ff.

- ↑ Bjørn Helland-Hansen, Fridtjof Nansen: The Norwegian Sea, its physical oceanography based upon the Norwegian researches 1900-1904. ( Memento from April 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) In: Fiskeridir. Skr. Ser. Havunders. 2 (2). 1909, pp. 390 ff. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen: The waters of the north-eastern north atlantic: investigations made during the cruise of the Frithjof, of the norwegian royal navy, in july 1910. Werner Klikhardt, Leipzig 1913. Norwegian National Library. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ↑ a b Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 179-184.

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen: Spitsbergen waters: oceanographic observations during the cruise of the "Veslemøy" to Spitsbergen in 1912 . ( Memento of September 6, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) In Commission at Jacob Dybward, Christiania 1915. Norwegian National Library. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ↑ a b Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 184-189.

- ↑ Cecilie Mauritzen: The science of the sea. In: Olav Christensen (editor): Nord! Fridtjof Nansen's legacy. Science in the far north. Fram Museum / University of Oslo, 2011, ISBN 978-82-8235-054-9 , p. 62.

- ↑ a b Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, p. 204.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 190-203.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 451-452.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 465-466.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 464.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 463.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 561.

- ^ Riffenburgh: Nimrod . 2005, p. 109.

- ^ Riffenburgh: Nimrod . 2005, pp. 164-167.

- ^ Riffenburgh: Nimrod . 2005, p. 165.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy . 1997, p. 216.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 464-465.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 564.

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen: In Northern Mists , Vol. I and Vol. II. Frederick A. Stokes, New York 1911. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 566-568.

- ↑ Cornelia Lüdecke: German polar research since the turn of the century and the influence of Erich von Drygalski . (PDF file; 10.7 MB) Dissertation (= Reports on Polar Research 158, 1995), p. 163 and 219.

- ↑ a b c d e Norway, Sweden & Union.Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 481-484.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 489-490.

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen: Norway and the Union with Scheden . FH Brockhaus, Leipzig 1905. Accessed October 5, 2011.

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen: Norge og foreningen med Sverige. Jacob Dybwads, Oslo 1905. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, p. 147.

- ↑ Scott: Fridtjof Nansen . 1971, p. 285: “ Now have all ways of retreat been closed. Now remains only one path, the way forward, perhaps through difficulties and hardships, but forward for our country, to a free Norway. ”

- ↑ Polly Schmincke: Norway celebrates 100 years of independence . Report on the homepage of Deutschlandradio Kultur from August 13, 2005. Accessed April 12, 2013.

- ↑ Terje Leiren: A Century of Norwegian Independence ( Memento from December 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 6.8 MB). In: Scandinavian Review 5. 2005, pp. 6-16.

- ↑ Scott: Fridtjof Nansen . 1971, pp. 202-205.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 513-516.

- ^ The Edinburgh Gazette, No. 11.833, p. 1181 of November 20, 1906 (English). Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ↑ Scott: Fridtjof Nansen . 1971, pp. 202-205: “ frivolous and boring ”.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 551.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 552-554.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, p. 214.

- ^ Pollok: The League of Nations . 2003, pp. 88-89.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 583.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, p. 216.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, p. 221: “ Never in my life have I been brought into touch with so formidable an amount of suffering. ”

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, p. 638.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 222-223: “ contain tales of heroic endeavor worthy of those in the accounts of the crossing of Greenland and the great Arctic voyage. ”

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 599-603.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, pp. 224-229.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, p. 230: “ There was in various transatlantic countries such an abundance of maize, that the farmers had to burn it as fuel in their railway engines. At the same time the ships in Europe were idle, for there were no cargoes. Simultaneously there were thousands, nay millions of unemployed. All this, while thirty million people in the Volga region — not far away and easily reached by our ships — were allowed to starve and die. ”

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, p. 241.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 649–650: “ his work for the repatriation of the prisoners of war, his work for the Russian refugees, his work to bring succor to the millions of Russians afflicted by famine, and finally his present work for the refugees in Asia Minor and Thrace ”.

- ^ A b Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 659-660.

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, p. 262.

- ↑ Scott: Fridtjof Nansen . 1971, p. 230: “ an unique opportunity for speaking in the councils of the world. ”

- ↑ Reynolds: Nansen . 1932, p. 247.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen . 2001, pp. 598, 664.