Nansen's Fram Expedition

The Fram Expedition (1893-1896) , led by the Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen, was a research trip to the Arctic with the aim of reaching the geographic North Pole using the natural ice drift in the Arctic Ocean . The idea for this expedition arose after the remains of the US warship USS Jeannette, trapped in the ice in June 1881 off the north coast of Siberia , three years later on the south-west coast of Greenlandhad been discovered. The theory of a transpolar drift flow developed on the basis of this find formed the basis for Nansen's expedition plans, which he presented to the Norwegian Geographical Society in February 1890 . Nansen received the necessary funding from the Norwegian government and from public institutions and private sponsors.

The expedition ship Fram , built especially for this research trip , had technical features that enabled it to withstand the pressure of the ice during the three-year ice drift without any damage. Despite numerous concerns from other polar explorers, Nansen and twelve companions drove the Fram to the New Siberian Islands in the eastern Arctic Ocean and left them there to freeze in the pack ice . In view of the low drift speed and the unpredictability of the drift direction, Nansen left the ship after 18 months in March 1895 to reach the North Pole on skis and with sled dogs together with Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen . Although they did not succeed in this, they set a new northern record with a latitude of 86 ° 13.6 'N. After a dangerous return trip over ice and open water, Nansen and Johansen rescued themselves on the offshore islands of Franz-Josef-Land , from where they returned to Norway. The Fram, for its part, reached the North Atlantic with the other expedition participants after a long ice drift .

The scientific observations carried out during the expedition made significant contributions to the then still young research discipline of oceanography , which became the central content of Nansen's scientific work. The ice drift of the Fram and the march to the north provided the first proof that there are no large land masses between the Eurasian continent and the North Pole and that the northern polar region is essentially characterized by icy deep sea . In addition, methods of survival and transport in polar regions were developed during this expedition, which were exemplary for all subsequent research trips to both the Arctic and the Antarctic .

prehistory

In September 1879, the penetrated Jeannette, a converted specifically for research trips to the Arctic gunboat of the US Navy , the pack ice north of the Bering Strait before. Her captain George W. DeLong was looking for the then missing Vega expedition (1878–1880) of Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld , who succeeded in crossing the Northeast Passage for the first time during this research trip . The Jeannette remained trapped in the ice for almost two years and drifted in the direction of the New Siberian Islands during this time until she sank on June 13, 1881 as a result of severe ice pressure off the mouth of the Lena . The team was initially able to save themselves in dinghies, but numerous expedition members including DeLong went missing in the wasteland of the Lena Delta. Three years after her sinking, wreckage of the Jeannette appeared more than 4,000 kilometers further west in the Julianehåb fjord on the southwest coast of Greenland. The items enclosed in the drift ice contained items of clothing with the names of the expedition participants Wilhelm Nindemann and Louis Philippe Noros (1850–1927) as well as documents that could be assigned to DeLong. There was no doubt about the authenticity of the find.

The Danish governor of Julianehåb, Carl Lytzen (1839-1896), after viewing the finds, believed that an expedition ship trapped by the ice off the coast of Siberia could reach South Greenland through the polar sea. In doing so, Lytzen anticipated the considerations of the then 23-year-old Fridtjof Nansen, who was working on his doctoral thesis as curator of the Bergen Museum and learned about the discovery of the wreckage through a report in the Norwegian newspaper Morgenbladet in autumn 1884. Nansen did not refer to Lytzen, however, but to the Norwegian meteorologist Henrik Mohn , who in a lecture at the Norwegian Academy of Sciences in November 1884 put forward the theory of a transpolar drift current, according to which the wreckage of the Jeannette indicated an indication of a westerly ocean current through the throughout the Arctic Ocean.

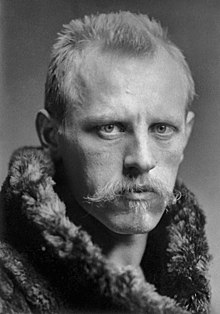

Nansen's previous knowledge of Arctic research was considerable. As early as 1882 he took part in a five-month voyage on the sealer Viking between Greenland , Jan Mayen and Spitzbergen , during which he researched the physical principles of the formation of sea ice in which the ship was trapped for three weeks. Finally, in 1888, according to plans that he had already developed during his student days, he succeeded in crossing Greenland for the first time across the inland ice . Soon after his return from this expedition, Nansen took up Mohn's theory again and published plans for a research trip based on it with the North Pole as a destination.

Preparations

Presentation of the expedition plans

In February 1890, Nansen revealed his plans at a meeting of the Norwegian Geographical Society in Christiania . In view of the failures of other expeditions to reach the North Pole from the west, Nansen made the discovery of the remains of the Jeannette the focus of his considerations: “If we summarize everything, it seems to us of necessity to draw the conclusion that somewhere between the Pole and Franz Josef Land a stream flows from the Siberian Arctic Ocean to the east coast of Greenland. ”Accordingly, according to Nansen, the task should be“ to pave our way into this current on the side of the pole, where it leads north to meet hers Help to advance into the regions that those tried in vain to reach who had worked against [the current] until then. "

Nansen's plans required a small, stable and agile ship that could be propelled by sail or motor power as required and that had enough space for fuel and provisions to feed twelve men over a period of five years. The ship was to follow the route of the Jeannette expedition and advance to the New Siberian Islands. As soon as the ice conditions allowed, "we should plow our way into the ice as much as possible." Security to arrive. Nansen noted: "If the Jeannette expedition had had enough provisions and had stayed on the ice in which their remains were finally found, the result would undoubtedly have been different from the one that finally occurred."

When Nansen's plans became public, the New York Times enthusiastically commented : "It is very likely that there is a comparatively short direct route through the Arctic Ocean across the North Pole and that nature itself provides a means of transport for this."

In professional circles, Nansen's plans were viewed with far more skepticism. In particular, his plan to deliberately steer the expedition ship into the pack ice was considered irresponsible. Previous research trips to the Arctic, during which the respective ships were crushed by the pack ice, had, like the Jeannette expedition, mostly ended catastrophically with the loss of numerous human lives. In view of this, Nansen was accused of frivolously endangering his life and that of his subordinates. The American polar explorer Adolphus Greely therefore considered Nansen's plan to be “an unreasonable program of self-destruction”. David Brainard (1856–1946), who during Greely's Lady Franklin Bay Expedition (1881–1884) on May 13, 1882 together with James Booth Lockwood (1852–1884) and Frederick Christiansen (1846–1884) at 83 ° 24 ′ N, who set a new northern record, called it "one of the most ill-advised models ever set" and predicted that the expedition was doomed. Sir Allen Young (1827-1915), a veteran of the search expeditions for the missing Franklin expedition , did not believe that a ship could be constructed that could withstand ice pressure: "[...] the ice will penetrate through them, no matter what material it is made of. ”Sir Joseph Hooker , who had accompanied James Clark Ross on his Antarctic expedition (1839–1843), was of the same opinion and considered the associated risk to be intolerable. Sir Leopold McClintock saw Nansen's project as "the greatest adventure that the Royal Geographical Society has ever presented."

financing

The Swedish philanthropist Oscar Dickson , who in connection with the sinking of Jeannette standing Vega expedition Adolf Erik Nordenskiold for the first time Durchfahrung the Northeast Passage had financed (1878-1880), bot, impressed by Nansen's plans, which incurred for research travel costs to take over. In the wake of burgeoning nationalism and efforts in Norway to end the personal union with Sweden, which had existed since 1814, this gesture from the neighboring country led to hostile comments in the Norwegian press. Nansen decided to turn down Dickson's offer and initially only take financial support from Norway.

According to Nansen's initial calculation, the cost of the expedition was 300,000 Norwegian kroner (NOK), an amount that today (as of 2011) corresponds to around 1.58 million euros . After a passionate speech at Storting , the Norwegian government provided him with NOK 200,000. The remaining funds were raised by private sponsors, including NOK 20,000 from King Oskar II of Sweden . The Royal Geographical Society in London presented him with £ 300 (today: around £ 33,000).

As it soon turned out, Nansen had seriously underestimated the financial needs. In particular, the cost of building the expedition ship prompted him to turn to the Norwegian Parliament again. He received a further NOK 80,000 and an additional public appeal finally raised a total of NOK 445,000 (2011: around EUR 2.34 million). According to Nansen's account, he paid part of the shortfall from his own resources. According to another account, the remaining NOK 12,000 was raised by businessmen Axel Heiberg and Charles Dick (1836–1904).

Expedition ship

For the construction of his expedition ship, Nansen chose the then leading ship designer in Norway, the Scottish boat builder Colin Archer . Archer was known for its special hull design, which combined high stability with exceptional seaworthiness . By he developed a combination of a convex stem with a Spitzgatt was maneuverability of the actually inert, barrel-type hull increased. The plans for the construction of the Fram were initially very tough. Nansen noted: “Archer developed one plan after another for the [...] ship; one model after the other was prepared and discarded. ”Finally, the two men agreed on a design and signed a contract on June 9, 1891 to build the Fram . Nansen insisted that the ship be completed within a year, fearing that someone else might usurp his plans and get ahead of him.

The Fram was rigged as a three-masted schooner with a total sail area of 560 square meters . With a standard displacement of 400 tons , it far exceeded Nansen's original requirement of 170 tons. The auxiliary engine, a triple expansion steam engine with an output of 220 hp (162 kW), enabled speeds of up to seven knots . However, speed and sailing characteristics were of secondary interest. The actual task of the Fram was to provide the expedition participants with safe and warm quarters during their drift through the pack ice, which could possibly be several years. Therefore, special emphasis was placed on the thermal insulation of the cabins.

The most prominent feature of the ship was the hull construction with its oval cross-section, which robbed the ice of any possible target. The bow and stern were rounded and the planks smoothed so that, in the words of Nansen, the ship “can slip out of the grip of the ice like an eel.” The rudder and propeller could be retracted so that they could not be damaged by the pressure of the ice. In order to increase the strength of the hull, the planks of the ship were made from the particularly hard green heart wood. The three-layer fuselage had a wall thickness of 60 to 70 centimeters, which increased to up to 1.25 meters at the steel-reinforced bow. Additional stability was achieved through cross struts and ribs that were inserted over the entire length of the fuselage. The unusual 3: 1 ratio of the ship's length (39 meters) to the width (eleven meters) gave the Fram a squat appearance. Colin Archer explained: "[...] a ship that is built to meet the special needs of the project must necessarily deviate [from the usual shape]." It was launched on October 6, 1892, after Nansen's wife Eva ( 1858–1907) had carried out the christening of the ship as part of a brief ceremony .

team

Already during his Greenland expedition (1888–1889), Nansen deviated from the previously common practice on polar expeditions of using expedition members and material on a large scale. Even now he relied on a small, well-trained team. From the thousands of applications that he received from all over the world after his plans were announced, Nansen selected only twelve companions. One of the applicants was Roald Amundsen , who was just 20 years old , but his mother prevented participation in the expedition. The British polar explorer Frederick George Jackson also applied to participate, but Nansen wanted his team to be composed entirely of Norwegians. Jackson then organized his own expedition to Franz Josef Land , which went down in the history of polar research as the Jackson Harmsworth Expedition (1894-1897).

Nansen appointed the experienced sailor Otto Sverdrup to be the captain of the Fram and deputy expedition leader , who had already taken part in the crossing of Greenland with him and who later became an important polar explorer himself. The helmsman Theodor Jacobson (1855–1933) also had experience in polar waters as a skipper on board a sloop . Navy Lieutenant Sigurd Scott-Hansen (1868–1937), the youngest member of the expedition, was the first officer responsible for the meteorological and magnetic investigations. Henrik Blessing (1866–1918), who had just finished his medical studies shortly before the start of the expedition, acted as ship's doctor and botanist . The reserve lieutenant and sled dog expert Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen was so keen on taking part in the expedition that he hired the only vacant post as a stoker . Similarly, Adolf Juell (1860–1909), a seaman with 20 years of experience as a helmsman and captain, became the Fram's smut . Ivar Mogstad (1856–1928) actually worked as a civil servant at the Gaustad Psychiatric Hospital at Christiania, but Nansen was more impressed by his skills as a mechanic. The oldest participant in the expedition was the chief engineer Anton Amundsen (1853–1909). The assistant engineer Lars Pettersen (1860–1898) kept his Swedish citizenship hidden from Nansen. Although this was soon discovered by his comrades, he was allowed to remain on board the Fram as the only non-Norwegian member of the expedition. The remaining participants consisted of the harpooner Peter Henriksen (1859-1932), the electrician Bernhard Nordahl (1862-1922) and Bernt Bentzen (1860-1899), who was quickly accepted into the team before the ship left Tromsø .

Expedition trip

Immediately before the start of the expedition, Nansen decided to deviate from his originally planned route. Instead of following the Jeannette's route over the Bering Strait to the New Siberian Islands , he decided to take the shorter and, in his opinion, safer route from Nordenskiöld's successful northeastern passage .

Drive into the pack ice

The Fram left Christiania on June 24, 1893 to the cheers of thousands of onlookers and accompanied by gun salutes fired from the cannons of Akershus Fortress . The ship reached Bergen on July 1st . On July 5th, the Fram called Trondheim , a week later she crossed the Arctic Circle . The last intermediate port in Norway was Vardø , which was reached on July 18th.

The first section of the journey into the eastern Arctic Ocean led the Fram through the Barents Sea to Novaya Zemlya and the northern Russian settlement of Chabarova (Russian: Хабарова; 69 ° 39 ′ N , 60 ° 24 ′ E ), where the crew led the first group of sled dogs Took board. On August 3, the Fram advanced to the icy Kara Sea , which it reached the following day. Only a few ships had previously sailed into the Kara Sea and the map material was incomplete. On August 18, Captain Sverdrup from the Fram 's crow's nest sighted a hitherto unknown island in the area of the mouth of the Yenisei , which Nansen named Sverdrup Island after its discoverer . It was the first of a series of hitherto unknown small islands that Nansen and his men discovered during the further voyage. The ship was now heading towards Cape Chelyuskin at the tip of the Taimyr Peninsula , the northernmost mainland point on the Eurasian continent . The expedition participants also experienced the flow phenomenon of dead water , in which the movement of a ship is hindered by the friction of a fresh water layer that settles on the denser salt water. Thick pack ice slowed progress and at the end of August the ship was trapped in the ice for four days, during which the crew repaired and cleaned the steam boiler. On September 9, 1893, a wide, ice-free channel opened and the Fram was the first ship to go to Nordenskiölds Vega in 1878 to circumnavigate Cape Chelyuskin to enter the Laptev Sea.

Since pack ice prevented a trip to the mouth of the Olenjok , where a second group of sled dogs should be taken on board, Nansen now set a north-easterly course in the direction of the New Siberian Islands. He hoped to find clear water up to 80 degrees north latitude. This hope was dashed when ice was sighted south of the 78th parallel on September 20. The Fram drove along the edge of the ice before finally anchoring in a small bay beyond 78 degrees north latitude. On September 28, Nansen realized that the ice was not going to break. In preparation for the ice drift, the team quartered the dogs from the cramped crates on board in dog houses specially built on the ice. On 5 October the rudder was hoisted on board and "moored thoroughly and conscientiously for the winter." The ship as shown Scott Hansen His position was 79 ° N , 133 ° O .

First phase of the ice drift

On October 9, 1893, the Fram was exposed to ice pressure for the first time. Archer's hull design has now proven itself, as the ship was raised when the ice pressure increased and sank when the ice pressure decreased, without the ice finding a point of attack on the hull. On the other hand, the first few weeks in the pack ice were disappointing, as the ice drift unpredictably moved the ship temporarily north and south. On November 19, after six weeks of ice drift, the ship was at a more southerly latitude than at the beginning.

After the polar night set in on October 25th, electric lights powered by electricity from a wind-powered generator illuminated the ship. At that time, everyday life on board was dominated by monotonous routine and boredom. The men were irritable and there were occasional violent arguments. To counteract this development, Nansen planned to jointly create an expedition magazine. However, this project met with little interest from the other expedition participants. Short explorations and some scientific measurements were the only diversions. Nansen expressed his frustration in his diary: “I feel that I have to break through this lifelessness, this indolence and find an outlet for my energy.” A few days later he wrote: “Can not something happen? Can't a hurricane come up and break up this ice? ”Only at the turn of the year 1893/1894 did the ice drift move the ship in a more constant northerly direction. On February 2, the Fram finally crossed 80 ° north latitude.

Due to the unpredictable drift direction and the low drift speed, Nansen calculated that it could take up to five years for the ship to reach the North Pole in this way. In January 1894, Nansen and Henriksen and Johansen discussed the possibility of a dog sled trip to the North Pole, but without taking any concrete action. Nansen's first attempts with the sled dog were unsuccessful, but he was not discouraged and got increasingly better results. He made the experience that he could reach the same speed on cross-country skis as dogs pulling a fully loaded sled. According to the polar historian Roland Huntford , this realization was a breakthrough in the development of polar means of transport. On May 19, two days after the Norwegian Constitution Day celebrations , the Fram reached latitude 81 degrees north. Although the drift speed had increased somewhat, it was still significantly less than two kilometers per day. More and more convinced that the North Pole could only be reached by dog sledding, Nansen had the men train two hours a day on skis in September. On November 16, 1894, he announced his intentions to the crew: he and a companion would leave the ship as soon as a north latitude of 83 ° was reached. After they had reached the North Pole, the two men would make their way back to Franz-Josef-Land and finally to Spitzbergen to be picked up by the Fram for the journey home. Three days later, Nansen asked the most experienced dog handler of his team, Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen , to accompany him on this trip.

In the following months, the team prepared for the planned march to the North Pole. The sledges have been prepared for rapid progress on uneven terrain. The expedition participants also built kayaks modeled on the Eskimos for trips in open water. Nansen had clothing and other equipment tried out countless times. On January 3, 1895, violent and prolonged shocks shook the ship. The crew disembarked two days later, expecting the Fram to be crushed by the ice. But the ice pressure decreased and the crew continued their preparations on board. On January 8, the Fram reached a latitude of 83 ° 34 'N, with which Nansen's expedition had broken the old northern record of May 13, 1882 through Brainard, Lockwood and Christiansen at 83 ° 23.8' N.

March north

On February 17, 1895, Nansen wrote a farewell letter to his wife Eva in case the expedition failed. In the following weeks he also read the available literature on Franz Josef Land, the planned retreat area after the march to the Pole. The archipelago was discovered during the Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition (1872–1874) and has not yet been fully mapped. However, Nansen knew from Julius von Payer's descriptions that there were numerous polar bears and large seal populations there that were possible sources of food for the return journey to civilization.

On March 14th, when the Fram had reached a latitude of 84 ° 4 'N, Nansen and Johansen started their march. It was the third attempt. On February 26 and 28, after having covered short distances on both occasions, the two men returned to the ship due to damage to their sleds. Before the new departure, Nansen had all the equipment overhauled and minimized the luggage. The latter measure and a recalculation of the payload made it possible to distribute the entire cargo to three instead of the four sledges as before. Nansen and Johansen were supported by an escort team on the first stage of the day. The following day they continued their journey alone.

The terrain that both men traversed on their way north consisted mainly of flat snow fields. Nansen had determined to cover the remaining 660 kilometers to the North Pole within 50 days, which corresponded to a daily workload of the equivalent of 13 kilometers. A position determination by means of a sextant on March 22nd showed that despite icy temperatures of down to −40 ° C and some setbacks, which also included the loss of the distance meter, by then they had covered 120 kilometers with a daily workload of 17 kilometers . However, the terrain became increasingly uneven, which made it difficult and slower to advance on skis. A position determination on March 29th showed that they had come only 87 kilometers closer to the pole within a week and thus the initially high daily workload could no longer be met. In addition, the position determination carried out on the same day using theodolite (85 ° 15 ′ N) deviated from that using the sextant (85 ° 56 ′ N) in an inexplicable way and the two men did not know which of the two measurements was the correct one. They realized that they were marching against a southern ice drift and that with the daily distances they had covered, they were shortening the rest of the way to the pole far less than they had hoped. Johansen's diary reveals the increasing discouragement of the two men: “All my fingers have been destroyed. The gloves are frozen stiff ... It's getting worse and worse ... God knows what will become of us. "

On April 3rd, after days of arduous advancement, Nansen realized that despite their best efforts, the North Pole might be out of their reach. Even if they moved through simpler terrain, their food supplies would not be sufficient to get to the pole and then to Franz-Josef-Land. A position fix the next day gave a disappointing result of 86 ° 3 ′ N. Nansen wrote, "I am more and more convinced that we should turn back prematurely." After they camped on April 7th, Nansen set out on a scouting tour for their further way north, but the only thing he saw was "a real mess of ice blocks that stretched to the horizon." He decided not to go any further and instead headed for Cape Fligely on Franz Josef Land. The last position determination on April 8th showed a north latitude of 86 ° 13.6 ′, with which Nansen and Johansen exceeded the previous north record by almost three degrees of latitude.

Retreat to Franz-Josef-Land

By changing direction to the southwest, Nansen and Johansen encountered significantly better marching conditions, probably because they were now traveling parallel to the faults in the ice instead of running towards them directly. They made rapid progress and on April 13, 1895, Nansen noted: "If things continue like this, the way back will be finished sooner than I thought." Nevertheless, there were also setbacks. On the same day, both men found that their chronometers had stopped. While Nansen downplayed the process, it was a serious incident. Due to the failure of the chronometer, they could not determine the longitude exactly in order to follow the correct route to Franz-Josef-Land. If they moved further west than Nansen believed, they risked missing the archipelago and headed for the open Atlantic instead.

The ice drift was given a north-westerly direction, which hindered its progress. On April 18, eleven days after leaving the northernmost point of their march, they had only traveled 74 kilometers south. The two men now traversed a fragile area with extensive areas of open water. On April 21st, to their delight, they encountered a large piece of driftwood in an ice floe as the first sign of animate nature beyond the supposedly inanimate ice desert since they had left the Fram . Johansen scratched his and Nansen's initials as well as the date and longitude. On April 26th, they discovered the trail of an arctic fox in the snow . They later found more leads, and Nansen assumed they were near land . The latitude of 84 ° 3 'N, determined on May 9, was disappointing, however, because Nansen had hoped to be much further south in the meantime.

A few days later they spotted polar bear tracks and in late May they encountered large groups of seals, sea birds and whales . According to Nansen's calculations, they had reached 82 ° 21 ′ north on May 31. Cape Fligely was only 93 kilometers away from them, as long as Nansen's longitude determination was correct. As the weather got warmer, the ice began to break up, which made it difficult for the two men to move forward. Since April 24, they had killed some of their sled dogs at regular intervals and fed them to the others. At the beginning of June, only seven of the original 28 animals were left. On June 21, they left much of their equipment and supplies behind to travel light and feed on seals and seabirds that they hunted along the way. The next day they set up their quarters on an ice floe. For the next four weeks, the men were busy repairing defective parts of the remaining equipment, drying damp ammunition and checking the seaworthiness of their kayaks. The long stay, however, served in particular to recuperate for the rest of the way.

On July 24th, the day after they set out again, Nansen saw land for the first time after two years of drifting and wandering through the icy desert of the Arctic Ocean . He wrote: “At last the miracle has occurred - land, land, after we had almost lost faith in it!” In the days that followed, they headed for this land mass and at the end of July they heard the sound of the surf landing in the distance . On August 5th, they survived an attack by a polar bear that appeared to have followed their trail. Two days later they reached the edge of the ice; an open expanse of water separated them from direct access to the land. On the same day they killed their last two dogs, converted their kayaks into a catamaran using sleds and skis, and set off for the crossing.

Nansen named the first island he visited, the current name of which is Eva Liv Island , after his wife Eva's Island . After setting up camp on the coast, they climbed a hill to get an overview. They were in the middle of a group of islands, which, however, could not be brought into agreement with their incomplete map of Franz Josef Land. Nansen named it "Hvidtenland" (Norwegian for "White Land"). Their hope was to find a landmark on the way south that could be clearly identified. On August 16, Nansen identified a headland as Cape Fields , which, according to Payer's map, was to be found on the west coast of Franz Josef Land. The goal was now to reach the so-called Eira Harbor at the south-western end of the archipelago and there a hut with supplies that had been built by the British Arctic Expedition (1881-1882) under Benjamin Leigh Smith . However, changing winds and drifting ice endangered the continued journey in the kayaks, so that Nansen decided on August 28, due to the approaching polar winter, to set up a winter camp on the southwest coast of the island later known as Jackson Island and wait there until the coming spring.

March to Cape Flora

Nansen and Johansen found a suitable location for their winter quarters in a sheltered bay with suitable building materials in the form of boulders and moss . They dug a cave about three feet deep in the snow, built walls of loose rubble and stones and stretched a roof made of walrus skin over the structure. They also made a fireplace from walrus bones . Their shelter, which they called "Das Loch" for short, was completed on September 28, 1895 and was their home for the next eight months. Her situation, while uncomfortable, was not life threatening. Jagbares Wild stood them in plenty. The main enemy was once again boredom. To pass the time, they read Nansen's sailing almanac and navigation tables several times in the light of a tran lamp .

The two men celebrated Christmas with chocolate and bread from their sleigh rations. On New Year's Eve , according to Johansen's description, Nansen offered him the "you" , after they had previously addressed each other formally as "Mr. Johansen" and "Professor Nansen". At the beginning of the new year, in preparation for the onward journey in warmer weather, they made simple jackets and pants from a discarded sleeping bag. After weeks of preparation, they finally resumed their march on May 19, 1896. Nansen left a message in the hut: "We are going to the southwest, following the land mass to get to Spitsbergen."

For more than two weeks they followed the coastline southwards. Again, none of the landmarks seemed to match their map of Franz-Josef-Land and Nansen wondered whether they were possibly in a previously unmapped area between Franz-Josef-Land and Svalbard. Due to a change in the weather on June 4th, they were able to continue their way in the kayaks for the first time since leaving winter camp. A week later, Nansen was only able to save both boats by jumping into the icy water after they had drifted away due to insufficient mooring. He reached her with the last of his strength and just managed to heave himself on board.

After walruses damaged both kayaks on June 13, the necessary repairs stopped Nansen and Johansen again. When they were about to leave on June 17th, Nansen thought he heard the barking of dogs. A little later he heard voices and finally saw a human figure. It was Frederick George Jackson , who, after Nansen's refusal, organized his own expedition to Franz Josef Land and set up his headquarters at Cape Flora on Northbrook Island , the southernmost land mass of the archipelago. According to Jackson's own account, he believed in a first reaction to the encounter with Nansen that he was possibly a shipwrecked sailor from his supply ship Windward , which he was expecting this summer. As they got closer, Jackson saw "a tall man who wore a soft felt hat, in loose, sweeping clothes and with long, shaggy hair and beard, all sooty with black goo." After a moment of embarrassed silence, Jackson recognized the person opposite : "You are Nansen, aren't you?", To which he replied: "Yes, I am Nansen."

Jackson took Nansen and Johansen to his base camp, where the two men initially posed for photos. In one of the photos, the encounter between Nansen and Jackson was recreated. Only then did they take a bath and have their hair cut. Despite the ordeal, both appeared to be in good physical shape. Nansen had put on nine and a half kilograms since the start of the expedition, while Johansen had put on almost six kilograms. In honor of their Savior, Nansen named the island where they camped for the winter "Frederick Jackson Island." In the next six weeks there was little for Nansen and Johansen to do other than wait for the Windward to arrive . Fearing that he would have to spend the coming winter at Cape Flora , Nansen regretted not having marched on to Spitsbergen with Johansen. Johansen noted in his diary that Nansen had changed from his arrogant manner at the beginning of the expedition to a more moderate and considerate mood, firmly convinced that he would never undertake such a journey again. On July 26th, the Windward finally arrived at Cape Flora . On August 7th, the ship sailed for Norway with Nansen and Johansen on board. They reached Vardø on August 13, 1896, and Nansen sent telegrams of his safe return.

Second phase of the ice drift

Before Nansen and Johansen left the Fram in March 1895, he had appointed Captain Otto Sverdrup to lead the rest of the expedition team. Sverdrup had received the order to continue with the ice drift until it reached the Atlantic, or to go to the nearest land with the other expedition members in the event of the expedition's sinking. Nansen had provided specific instructions for continuing the scientific work, in particular the depth measurement and the determination of the ice thickness . These ended with the sentence: "[...] and may we meet again in Norway, whether on board the ship or without it."

Sverdrup's main job was to keep the expedition crew busy. He let the ship from scratch cleaned and cut off the ice when the Fram threatened in through this list to fall. Even if there was no imminent danger that the ship overturned , Sverdrup nevertheless ordered the repair of the sledges and the inspection of the supplies in order to be able to abandon the ship and go ashore if necessary. When the weather improved in the summer of 1895, the captain prescribed daily ski training for the other participants in the expedition. In addition to these activities, a comprehensive meteorological, magnetological and oceanographic investigation program was completed under the direction of Scott-Hansen.

As the ice drift continued, depth measurements carried out several times showed that the ship was not in the immediate vicinity of a previously undiscovered land mass. On November 15, the Fram reached a latitude of 85 ° 55 'N and was thus only 35 kilometers further south than the northernmost latitude reached by Nansen and Johansen. From then on, the ice drift moved the ship in a constant south-westerly direction, although the drift was barely noticeable. Inactivity and boredom led to increased alcohol consumption among the expedition participants. Scott-Hansen wrote that Christmas and New Year passed them by "with the usual hot punch and the consequent hangover " and continued: "The binge disgusts me more and more."

In mid-March 1896 the Fram was at 84 ° N , 13 ° E and thus north of Spitsbergen. On June 13, a gully opened and the Fram escaped the ice for the first time after almost three years of drifting. But it was not until August 13, before the ship with a ceremonial gun salute of cannon came finally to the northwest of Spitsbergen into the open water, which Nansen's original assumption was confirmed about the direction of ice drift. Later that day, which attracted Fram on the sealers Søstrone from Tromso . When Sverdrup went on board, he learned that there was no news of the fate of Nansen and Johansen. The Fram then called at Svalbard, where the Swedish polar explorer Salomon August Andrée was preparing his trip to the North Pole in a hydrogen balloon . After a short stay on land, Sverdrup and the rest of the crew set off for Norway on board the Fram .

Meeting and reception in Norway

Even during the expedition, rumors were circulating that Nansen had reached the North Pole. A first article appeared in April 1894 in the French newspaper Le Figaro . In September 1895, Nansen's wife Eva was informed that messages from her husband "sent from the North Pole" had been discovered. In February 1896, the New York Times published a report by a supposed agent Nansens from Irkutsk , which spoke of the "discovery of the North Pole [...] in the middle of a mountain range". The President of the American Geographical Society (AGS), Charles P. Daly (1816–1899), called this "startling news" and continued, "If it is true, this would be the most important discovery in ages."

Other experts were much more skeptical about this and when Nansen finally arrived in Vardø, they saw themselves confirmed. It was there by chance that Nansen and Johansen met Henrik Mohn, the founder of the theory of a transpolar drift flow. On August 18, both polar explorers reached Hammerfest on board a mail ship , where they were given an enthusiastic welcome. Two days later Nansen received the news that Sverdrup had arrived safely in Skjervøy with the Fram and that the voyage was continuing to Tromsø. There, on August 21, 1896, there was an exuberant reunion between Nansen, Johansen and the other members of the expedition.

After a few days of recovery, the crew on board the Fram left Tromsø on August 26th. On their return voyage, they were enthusiastically welcomed in every intermediate port. Upon arrival in Christiania on September 9th, a squadron of warships escorted the Fram into the town's harbor, where, according to Roland Huntford, the largest crowd the town had ever seen cheered the crew frenetically. While Nansen and his family resided in the king's castle as guests, Johansen was completely overlooked during the celebrations. He wrote: "After all that, reality is not as wonderful as it appeared [to me] in the midst of our harsh existence."

Evaluation and aftermath

The usual practice of previous polar expeditions was to proceed with a large number of participants and a high cost of materials. In addition, there were the traditional Anglo-Saxon shipbuilding techniques, which were traditionally influenced by British polar explorers, and the selection of clothing and food, draft animals and alternative means of transport prescribed by them. The latter included the “man-hauling” criticized by Nansen as “senseless drudgery”, in which the entire payload is pulled on sledges by one's own physical strength on foot. As can be seen in retrospect, these strategies and techniques were often unsuccessful, often leading to the loss of the expedition ships and killing numerous expedition members. In contrast, Nansen's strategy of relying on a small and well-trained crew and his willingness to draw on the experience of the Sami and Eskimos enabled the expedition to proceed safely without major technical failures or loss of life.

Although Nansen's expedition failed to achieve its primary goal of being the first to reach the geographic North Pole, it nonetheless yielded important geographic and scientific discoveries. The then President of the Royal Geographical Society Sir Clements Markham was of the opinion that the expedition had answered "the whole question of Arctic geography". For the first time, it provided evidence that the North Pole is neither on land nor on a permanent ice sheet, but in the middle of a zone of moving pack ice. The Arctic Ocean presented itself as a deep-sea basin with no significant land masses north of the Eurasian continent, since otherwise they would have hindered the observed ice drift. However, Nansen did not rule out the possibility that there could be land near the Poles north of the American continent. Henrik Mohn's theory of transpolar drift flow had been confirmed. Furthermore, the Swedish physicist recognized Vagn Walfrid Ekman using during the ice drift of the Fram data collected shows that the ocean current from the prevailing wind direction moved in a characteristic way, which he called " Ekman spiral called" and in connection with the by the Earth's rotation caused Coriolis force is . The expedition's scientific observation program provided detailed oceanographic information about the northern polar region for the first time. The results obtained here have been published in six volumes.

During the entire expedition, Nansen experimented with the equipment, changed the shape and structure of the skis and sledges and tested the suitability of clothing, tents and cooking utensils, thereby revolutionizing the techniques of polar travel. In the years following the Fram expedition, well-known polar explorers sought Nansen's advice on equipment and means of transport, although not all of them followed his advice - mostly to their detriment. According to Roland Huntford's account, Roald Amundsen , Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton , who are considered the most famous personalities of the Golden Age of Antarctic exploration, were all Nansen's apprentices .

Nansen's achievements were never seriously questioned, although he did not remain free of criticism. So put Robert Peary asked why Nansen and Johansen had not returned after the march north to the ship after this three weeks had crossed after the departure of their way "ashamed he [Nansen] to go back so soon, or was it was a quarrel ... or did he go to Franz-Josef-Land for sensational reasons or out of profit-seeking? ” Adolphus Greely admitted his initial mistake about the expedition's chances of success, but he particularly emphasized Nansen's alleged breach of duty when he did the other expedition participants Hundreds of kilometers from safe land left to her own fate: "It is incomprehensible why Nansen could deviate so much from the most sacred duty entrusted to a commander of an expedition at sea." Nansen's reputation remained unaffected. A century after this expedition, British polar explorer Wally Herbert described the Fram's voyage as "one of the most inspiring examples of daring cleverness in the history of exploration."

The Fram's first research trip was also Nansen's last major expedition. In 1897 he received a research professorship in the field of zoology at the University of Christiania, where he became professor of oceanography in 1908. The publication of his travel experiences made him financially independent. In later years he served the now independent Norwegian kingdom in various positions and received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922 in recognition of his work as the League of Nations High Commissioner for Refugee Issues . Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen , on the other hand, was unable to return to normal life. After years of aimless wandering, private indebtedness and alcohol addiction, Nansen's mediation enabled him to participate in Roald Amundsen's South Pole expedition in 1910 . As a result of a violent argument with Amundsen in the Framheim base camp , Johansen was excluded from the group that made the successful march to the South Pole. He fell into deep depression and committed suicide shortly after the return of Expedition suicide . Otto Sverdrup remained captain of the Fram and undertook a four-year research trip to the Canadian-Arctic archipelago with her and a new crew, which also included Peter Henriksen, from 1898 onwards . In later years he helped raise funds to repair the Fram and to build a museum specially built for the ship on the Bygdøy peninsula (see Framuseum ). Sverdrup died in November 1930, just seven months after Nansen's death.

The northern record of Nansen and Johansen lasted a little more than five years before a group of three around the Italian polar explorer Umberto Cagni reached 86 ° 34 ′ N on April 24, 1900 , after leaving Franz-Josef-Land on April 11 with dogs and the sledge had broken open. The three men barely managed to return, while a three-person support group disappeared without a trace.

Nansen's Fram expedition was the model for 2019, led by the Alfred Wegener Institute launched Mosaic expedition .

literature

Literature cited

- Pierre Berton : The Arctic Grail . Viking Penguin, New York, NY 1988, ISBN 0-670-82491-7 .

- TC Fairley: Sverdrup's Arctic Adventures . Longmans, Green, London 1959.

- Fergus Fleming : Ninety Degrees North . Granta Publications, London 2002, ISBN 1-86207-535-2 .

- Wally Herbert: The Noose of Laurels . Hodder & Stoughton, London 1989, ISBN 0-340-41276-3 .

- Clive Holland (Ed.): Farthest North . Robinson Publishing, London 1994, ISBN 1-84119-099-3 .

- Roland Huntford : The Last Place on Earth . Pan Books, London 1985, ISBN 0-330-28816-4 .

- Roland Huntford: Nansen . Abacus, London 2001, ISBN 0-349-11492-7 .

- Frederick Jackson: The Lure of Unknown Lands . G. Bell and Sons, London 1935.

- Max Jones: The Last Great Quest . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2003, ISBN 0-19-280483-9 .

- Fridtjof Nansen: Farthest North . Harper & Bros., New York / London 1897 ( Vol. I - Internet Archive , Vol. II - Internet Archive ).

- Diana Preston: A First Rate Tragedy . Constable & Co., London 1997, ISBN 0-09-479530-4 .

- Beau Riffenburgh: Nimrod . Bloomsbury Publications, London 2005, ISBN 0-7475-7253-4 .

Supplementary German-language literature

- Fridtjof Nansen: In Nacht und Eis: Volumes I and II . FA Brockhaus, 1898.

- Bernhard Nordahl, Hjalmar Johansen: In Night and Ice: Volume III, Supplement . FA Brockhaus, 1898.

- Fridtjof Nansen: In Night and Ice: The Norwegian Polar Expedition. 1893-1896 . Edition Erdmann, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-86539-825-3 (original title: Fram over polhavet .).

Web links

- The first Fram Expedition (1893–1896) , website of the Fram Museum about the expedition

- Fram Expedition 1893–1896 , Photo Collection of the Norwegian National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Thomas O. Hiscott: http://www.geographicalsociety.org/images/gspaper00200155.pdf (link not available)

- ↑ Holland: Farthest North. 1994, pp. 89-95.

- ^ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North. 2002, pp. 218-29.

- ^ A b Carl Lytzen: Levninger fra Jeannette Expeditions paa Grønlands Vestkyst . In: Geografisk Tidsskrift. 8, 1885-1886, pp. 49-51. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North. Vol. I, 1897, pp. 17-18. - Internet Archive

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North. Vol. I, 1897, p. 14. - Internet Archive

- ^ Huntford: Nansen. 2001, pp. 21-27.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen. 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North. Vol. I, 1897, pp. 14-15. - Internet Archive

- ↑ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 24. - Internet Archive “ Putting all this together, we seem driven to the conclusion that a current flows at some point from the Siberian Arctic Sea to the east coast of Greenland. ”

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 29. - Internet Archive “ to make our way into the current on that side of the Pole where it flows northward, and by this help to penetrate into those regions which all who have hitherto worked against it have sought in vain to reach. ”

- ↑ a b Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, pp. 30-31. - Internet Archive

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, pp. 30-31. - Internet Archive “ we shall plow our way in amongst the ice as far as we can. ”

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 33. - Internet Archive

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 33. - Internet Archive “ If the Jeannette expedition had had sufficient provisions, and had remained on the ice-floe on which the relics were ultimately found, the result would doubtless have been very different from what it was. ”

- ↑ Has Nature Supplied a Route Around the North Pole? . In: The New York Times , November 13, 1892. Retrieved May 2, 2011. “ It is highly probable that there is a comparatively short and direct route across the Arctic Ocean by way of the North Pole, and that nature herself has supplied a means of communication across it. ”

- ^ Berton: The Arctic Grail , 1988, p. 489: “ an illogical scheme of self-destruction ”.

- ↑ Stein, Glenn M .: A Biographical Sketch of Gen. David L. Brainard, US Army (PDF; 72 kB) . FRGS 2007. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- ↑ Will Nansen Come Back? . In: The New York Times , March 3, 1895. Retrieved May 2, 2011. “ one of the most ill-advised schemes ever embarked on ”.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 45. - Internet Archive “ […] the ice must go through her, whatever material she is made of. ”

- ^ Berton: The Arctic Grail , 1988, p. 492.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 47. - Internet Archive

- ↑ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 241: “ the most adventurous program ever brought under the notice of the Royal Geographical Society. ”

- ↑ a b Calculations using Measuringworth and XE Currency Converter

- ↑ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 239: Nansen ended his speech with the words “May Norwegians show the way! May the Norwegian flag be the first to fly at the Pole! ”, According to the source:“ May Norwegians show the way! May it be the Norwegian flag that first flies over our Pole! ”

- ↑ Calculation using template: inflation .

- ↑ a b Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 240.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 56. - Internet Archive

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 214.

- ^ A b Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 183-84.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 59. - Internet Archive “ Plan after plan did Archer make of the projected ship; one model after another was prepared and abandoned. ”

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 186.

- ↑ a b Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, pp. 62-68. - Internet Archive

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, pp. 68-69. - Internet Archive

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 62. - Internet Archive “ should be able to slip like an eel out of the embraces of the ice. ”

- ^ A b Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 192-197.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 59. - Internet Archive “ […] a ship which is to be built with exclusive regard to its suitability for this object must differ essentially from any other previously known vessel. ”

- ^ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, pp. 237-238.

- ↑ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 241.

- ↑ Jacobsen, Theodor Claudius (1855–1933) , short biography on the website of the Fram Museum (English). Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ↑ Scott Hansen, Sigurd (1868–1937) , short biography on the website of the Fram Museum (English). Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ↑ Blessing, Henrik Greve (1866–1918) , short biography on the website of the Fram Museum (English). Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ↑ Juell, Adolf (1860–1909) , short biography on the website of the Fram Museum (English). Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ↑ a b Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, pp. 77-80. - Internet Archive

- ↑ Mogstad, Ivar Otto Irgens (1856-1928) , short biography on the website of the Fram museum park (English). Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 218.

- ↑ Amundsen, Anton (1853–1909) , short biography on the website of the Fram Museum (English). Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ↑ Petterson, Lars (1860–1898) , short biography on the website of the Fram Museum (English). Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 221-222.

- ↑ Hendriksen, Peder Leonard (1859–1932) , short biography on the website of the Fram Museum (English). Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ↑ Nordahl, Bernhard (1862–1922) , short biography on the website of the Fram Museum (English). Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ↑ Bentsen, Bernt (1860–1899) , short biography on the website of the Fram Museum (English). Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ↑ a b Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 243.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 206-207.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 222-223.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 103. - Internet Archive

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 225-233.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 157. - Internet Archive

- ^ A b c Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 234-237.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 238-239: “ Well and truly moored for the winter. ”

- ^ A b Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 242.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 246.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 245.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 247-252.

- ↑ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 244: “ I feel I must break through this deadness, this inertia, and find some outlet for my energies. ”,“ Can't something happen? Could not a hurricane come and tear up this ice? ”

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, p. 388. - Internet Archive

- ^ A b Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 257-258.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, pp. 287-290. - Internet Archive

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 260-261.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 262.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 268-269.

- ↑ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, pp. 246-247.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 275-278.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 288.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 599. - Internet Archive

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 285.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 132. - Internet Archive

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, pp. 90-105. - Internet Archive

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, pp. 132-139. - Internet Archive

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 302-307.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 308-313.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 322.

- ↑ a b Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 248.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 320: “ My fingers are all destroyed. All mittens are frozen stiff… It is becoming worse and worse… God knows what will happen to us. ”

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 166. - Internet Archive “ I begin to think more and more to turn back before the time we originally fixed. ”

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 169. - Internet Archive “ a veritable chaos of ice-blocks, stretching in as far as the horizon. ”

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 170. - Internet Archive

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 330.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 172. - Internet Archive “ If this goes on, the return journey will be quicker than I thought. ”

- ↑ a b Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 249.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 332.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 333-334.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, pp. 185-186. - Internet Archive .

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 334-336.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 339.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 343-346.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 346-351.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 318. - Internet Archive “ At last the marvel has come to pass - land, land! and after we had almost given up our belief in it! ”

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 364.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , 1897, pp. 329-331. - Internet Archive

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 365-368.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 370.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 344. - Internet Archive

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 373.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 375-379.

- ↑ Nansen: Farthest North , 1897, p. 451. - Internet Archive (See also: Photo of the remains of the camp from 2011 , photographed by Michael Martin , Spiegel Online, August 1, 2011. Retrieved August 1, 2011. )

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 378-383.

- ↑ a b Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 259.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 397-398.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 403-404: “ We are going south west, along the land, to cross over to Spitsbergen. ”

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 410-412.

- ^ A b Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, pp. 261-262.

- ↑ Jackson: The Lure of Unknown Lands , 1935, pp. 165–166: “ a tall man, wearing a soft felt hat, loosely made, voluminous clothes and long shaggy hair and beard, all reeking with black grease. ”

- ↑ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 530. - Internet Archive “ You are Nansen, aren't you? ”,“ Yes, I am Nansen. ”

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 540. - Internet Archive

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 550. - Internet Archive “ Frederick Jackson's Island ”.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 570. - Internet Archive

- ↑ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 263.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 433-434.

- ↑ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 98. - Internet Archive “ […] and may we meet again in Norway, whether it be on board of this vessel or without her. ”

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 315-319.

- ↑ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 245.

- ↑ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, p. 252.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 423-428: “ with the usual hot punch and consequent hangover ”, “ getting more and more disgusted with drunkenness ”.

- ^ A b Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 423-428.

- ^ Berton: The Arctic Grail , 1988, p. 498.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 393.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 393: “ sent from the North Pole ”.

- ^ Nansen's Arctic Travel; Siberian Report of His Discovery Confirmed or Reiterated . In: The New York Times , February 15, 1896. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ Nansen's North Pole Search . In: The New York Times , March 3, 1895. Retrieved May 2, 2011. “ startling news ”, “ if true, the most important discovery that has been made in ages. ”

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, pp. 583-585. - Internet Archive

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 435-436.

- ^ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, pp. 264-265.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 438.

- ↑ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, pp. 264-265: “ Reality, after all, is not so wonderful as it appeared to me in the midst of our hard life. ”

- ^ Huntford: The Last Place on Earth , 1985, p. 10.

- ↑ a b James A. Aber: History of Geology: Fridtjof Nansen 1861–1930 . Emporia State University. 2006. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ↑ Jones: The Last Great Quest , 2003, p. 63: “ the whole problem of Arctic geography ”.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, pp. 708-711.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, p. 708.

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. II, 1897, pp. 112-131. - Internet Archive

- ^ A b Huntford: Nansen , 2001, pp. 1-2.

- ^ Riffenburgh: Nimrod , 2005, p. 120.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy , 1997, p. 216.

- ↑ Herbert: The Noose of Laurels , 1989, p. 13: “ Was he ashamed to go back after so short an absence, or had there been a row… or did he go off for Franz Josef Land from sensational motives or business reasons? ”

- ^ Nansen: Farthest North , Vol. I, 1897, pp. 52-53 “ It passes comprehension how Nansen could have thus deviated from the most sacred duty devolving on the commander of a naval expedition. ”

- ^ Herbert: The Noose of Laurels , 1989, p. 13: “ one of the most inspiring examples of courageous intelligence in the history of exploration. ”

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 442.

- ↑ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 560 and p. 571.

- ^ Fairley: Sverdrup's Arctic Adventures , 1959, pp. 12-16.

- ↑ Fairley: Sverdrup's Arctic Adventures , 1959, pp. 293-295.

- ↑ Fairley: Sverdrup's Arctic Adventures , 1959, p. 296.

- ^ Huntford: Nansen , 2001, p. 666.

- ↑ Fleming: Ninety Degrees North , 2002, pp. 316-332.

- ↑ Antje Boetius : Farewell, MOSAiC team! In: Special edition of the Alfred Wegener Institute newspaper, September 2019 (PDF; 3.4 MB). Retrieved January 12, 2020.