Robert Falcon Scott

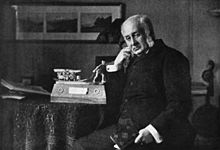

Robert Falcon Scott (born June 6, 1868 in Devonport near Plymouth , England , † March 29, 1912 on the Ross Ice Shelf , Antarctica ) was a British naval officer and polar explorer . He led the Discovery Expedition (1901–1904) and the Terra Nova Expedition (1910–1913), two research trips during the so-called Golden Age of Antarctic exploration . He is one of the first ten people to reach the geographic South Pole .

First, Scott went through an officer career in the Royal Navy . When his career stalled, he took the opportunity to take command of the research vessel Discovery . According to his own admission, this decision arose from his personal ambition and not from a particular predilection for polar research.

During the Discovery Expedition he led, he undertook an advance towards the South Pole with Edward Wilson and Ernest Shackleton between November 1902 and February 1903 , during which the three men set a new south record by reaching the latitude of 82 ° 17 ′ S. Scott's decision after his return to base camp to send Shackleton home against his will, who in his opinion was unfit for duty, gave rise to a discussion that is still going on today about a deep rivalry between the two polar explorers.

After Shackleton narrowly failed in his own attempt to reach the South Pole during the Nimrod Expedition (1907-1909), Scott made another attempt on the Terra Nova Expedition. This developed into a competition with the Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen . Scott reached the Pole on January 18, 1912, realizing that Amundsen and his crew of four had gotten ahead of him about a month. On the way back to base camp, Scott and his four companions died of malnutrition, illness and hypothermia.

In his homeland, Scott was stylized as a self-sacrificing national hero for decades because of his heroic death. It was not until the end of the 20th century that a more differentiated view and re-evaluation of his person began.

Youth and officer career

Origin and youth (1868–1883)

Robert Falcon Scott was on the family estate Outland House in Stoke Damerel, a parish near the naval base Devonport in southwest England Plymouth , the third of six children (according to another source, the fourth of seven children) of the brewery owner John Edward Scott (1830-1897) and its Ms. Hannah (née Cuming, 1841–1924) was born. His grandfather and his brothers already owned some breweries and grocery stores in Plymouth through profits from the Napoleonic Wars , which had helped the family to prosper.

At the beginning of his schooling, Scott was homeschooled; only at the age of eight he attended the local school in Stoke Damerel. The author Diana Preston describes him as a late developer , physically rather weak, and as a sensitive and shy daydreamer , "who [the sight of] blood was terrible and who loved solitude". Despite these perceived flaws, which he tried to hide throughout his life, his life, following the example of his uncles as officers in the British Indian Army, was destined for a military career. At the age of twelve, his parents sent him to the Stubbington House School , a renowned cramming school for aspiring cadets in the county of Hampshire . In 1881 Scott passed the entrance exams to the Royal Navy , which enabled him to train on the training ship HMS Britannia .

After two years of training Scott left in 1883, the HMS Britannia in the rank of midshipman as seventh Best of 26 midshipmen in his class. In October of the same year he went to South Africa to take up his service on board the flagship of the South African squadron, the Corvette Boadicea . This was the first of a series of ships on which he spent his time as an officer candidate. In 1887, Scott was stationed on the HMS Rover on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts . There they met Clements Markham for the first time on March 1st . Scott was noticed by the then Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society that day as a member of the winning team of a cutter regatta . Markham was on the lookout for young naval officers who were potential candidates for polar expeditions and, in his own words, was impressed by the "intelligence, dedication and [...] charisma" of 18-year-old Scott.

In March 1888 Scott passed the examination to lieutenant with four out of five possible top marks, and only a year later he was promoted to lieutenant . After a total of eight years of service in foreign waters, he returned to England in 1891 to begin the prestigious training to become a torpedo boat captain. Scott completed this training with top marks in theory and practice, although he had earned a rebuke in 1893 after his boat ran aground due to inattention .

Even beyond this incident, Scott's navy career did not go smoothly. When researching his book Scott and Amundsen (later republished under the title The Last Place On Earth ), the biographer and specialist in polar explorer Roland Huntford uncovered loopholes in Scott's personnel file at the Royal Navy between mid-August 1889 and March 26, 1890. Huntford attributes this to Scott's unauthorized departure from service in connection with a love affair with an unnamed American woman, which is said to have been tolerated and concealed by his superiors. Scott's biographer David Crane came to a similar conclusion in his research, but disliked Huntford's interpretation. Scott had neither the position nor the necessary connections in the Navy to cover up the matter. There is no further evidence in the British Admiralty's records that could clarify the matter.

From 1894 onwards, a series of blows of fate shook Scott's life. As an officer of the torpedo boat HMS Vulcan , he learned that his father had lost all of his family's fortune after the brewery was sold and the bad investments made with serious consequences. At the age of 63 and in poor health, John Edward Scott was forced to work as a simple brewery worker in Shepton Mallet, Somerset , to support his family. In 1897, while Robert was serving on the flagship of the Canal Squadron, HMS Majestic , the death of his father plunged the Scott family into an existential crisis. Robert's mother Hannah and his two unmarried sisters became dependent on his wages and the income of his younger brother Archibald. He had quit his service with the army in order to take a higher-paid post in the Colonial Service . When Archibald Scott died of typhus in the fall of 1898 , Robert was the only provider left.

The search for opportunities to advance his career and thereby earn better income became the mainspring in Scott's life. The Royal Navy offered him few opportunities for advancement during this time. At the beginning of June 1899 he happened to meet the now ennobled Sir Clements Markham while on home leave in London and learned from him about the upcoming Antarctic expedition led by the Royal Geographical Society , of which Markham had been president since May 1893. For Scott it was a welcome opportunity to get his own command early on and to distinguish himself as the captain of a well-known ship. Just a few days after that meeting, on June 11th, Scott appeared at Markham's estate to apply for the post of expedition leader.

Discovery Expedition (1901-1904)

The National Antarctic Expedition , as the Discovery Expedition was officially known, was a joint venture of the Royal Geographical Society and the Royal Society . The plans for the implementation of the first research trip to the Antarctic continent undertaken exclusively under British leadership since James Clark Ross around 60 years earlier were promoted by Markham from 1893. The objectives were general scientific and in particular geographical explorations in the Antarctic.

Appointment as expedition leader

Scott's bid to host the expedition leader was, who had participated in the years 1875/1876 at an Arctic expedition by his superior, Captain George Egerton (1852-1940), the acting First Lord of the Admiralty George Goschen and the former First Sea Lord Walter Kerr supports . There was resistance to this from the Royal Society, which demanded a scientific expedition leader. Markham managed to play off the representatives of the Royal Society in the commission formed with the Royal Geographical Society against each other and to enforce his preferred candidate, so that Scott transferred command of the expedition ship Discovery on June 9, 1900 and he was promoted to the rank of June 30th Commanders was raised. Contrary to his own account, Markham had apparently considered other applicants than Scott.

Course of the expedition

Although none of the 50-strong crew, including Scott, had any significant knowledge and experience of survival in polar regions, little time was spent preparing the men for their upcoming duties or adequately testing the equipment. When the Discovery set off from Cardiff on July 31, 1901 for a trip south, no one knew about the practical handling of the sled dogs and skis that were carried along. This negligence cost the sailor George Vince (1879-1902) his life when he lost his footing on March 11, 1902 because of wearing treadless fur boots on an icy cliff not far from the base camp (now known as Danger Slopes ) and when he fell into the sea disappeared without a trace. Vince was already the second victim that Scott had to answer as leader of the expedition, after the cocky sailor Charles Bonner (1878-1901) fell to his death on December 21, 1901 in the port of Lyttelton from the main mast of the ship.

Aside from these two incidents, Scott and his men did significant pioneering work and made important geographical discoveries. After landing in a small bay in the eastern section of the Ross Ice Shelf , he himself took part in the first ascent of a balloon in Antarctica on February 4, 1902. In addition, with the Edward VII Peninsula, the eastern boundary of the ice shelf was discovered a few days earlier. The Discovery Expedition was the first research expedition in which members of the expedition wintered in Antarctica for two consecutive years. On October 16, 1903, Scott and eight other men were the first to set foot on the polar plateau in northern Victoria Land after climbing the Ferrar Glacier . The scientific investigations during the expedition provided new zoological and geological insights into the Antarctic. Some of the meteorological and magnetological work were later criticized as amateurish and imprecise. Scott himself described the work of his chief geographer Charles Royds as "terribly sloppy."

The most important undertaking of the expedition, however, turned out to be the march south across the Ross Ice Shelf. The South Pole was not the real goal, although it was of great importance to Scott to reach as high a southern latitude as possible. He chose Edward Wilson, a doctor, zoologist and illustrator, and the third officer Ernest Shackleton to accompany him . After setting out from base camp on the Hut Point Peninsula on November 2, 1902, the three men reached a latitude of 82 ° 17 ′ S on December 30, around 860 km from the Pole, thus surpassing the previous southern record Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink at 78 ° 50 ′ S on February 16, 1900 by about 385 km. Their progress was hampered by the lack of experience in handling the sled dogs and the fact that the animals fell ill from spoiled food and eventually all perished. The way back, on which Scott, Wilson and Shackleton suffered from snow blindness , frostbite and also from scurvy , became a race against hunger and cold. According to Scott's account, Shackleton suffered a "total [physical] collapse" in the meantime, due to which Scott forced his subordinates to return home on February 4, 1903 after returning to base camp.

At the end of the expedition, the Admiralty dispatched two ships to rescue Discovery, which was trapped in McMurdo Sound from the ice . It was only through the use of explosives that it was possible to maneuver the expedition ship into open waters on February 16, 1904. After the experiences during the march south, Scott came to the later momentous assessment that sled dogs and skis were not suitable means of transport for traveling in Antarctica. He preferred what is known as man-hauling. in which the entire payload is pulled on sledges by one's own physical strength on foot, since "no journey made with dogs could ever achieve the ideal value that men left on their own in the face of hardship, danger and difficulties [...] Scott's stoic adherence to military manners had led to tension between the civilian and the Royal Navy expedition members, so that at the end of the first season, many members of the merchant navy in particular left the expedition. Scott had also offered his deputy, Albert Armitage , to return home in March 1903. Armitage took this as a deliberate provocation to him and declined the offer. In later years he strongly argued that Scott Ernest Shackleton was fired prematurely not because of health problems, but because he felt Shackleton's leadership and popularity with other expedition members as a threat to his authority as an expedition leader.

Feedback after returning

The reception of the expedition members in England by the Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society was initially very subdued. When the Discovery arrived in London in September 1904, no representative of the learned societies involved appeared to greet them. The enthusiasm and interest in the British public, however, were enormous, so that Scott and his companions finally received official recognition for the achievements of the expedition. Scott has received a variety of awards and medals of honor from home and abroad. In an invitation to Balmoral Castle King named him Edward VII. To the Commander of the Royal Victorian Order , and in France, he was Officer's Cross of Merit of the Legion of Honor awarded. The Royal Geographical Society presented him with the Patron's Medal in gold, and the Admiralty donated the Polar Medal for Scott and his crew. Scott was promoted to sea captain by the Royal Navy .

Marriage and social advancement

His fame gained through the Discovery Expedition gave Scott access to higher levels of society. In this way he met Kathleen Bruce in the spring of 1907 . The ten years younger woman was a confident, cosmopolitan artist, who as a student of Auguste Rodin , the sculpture had learned and their circle of Picasso , Isadora Duncan and Aleister Crowley belonged. Scott, now deputy director of intelligence for the British Admiralty, was drawn to the independent woman and asked for her hand. Scott was not the only applicant, however, and his absence as captain of HMS Victorious , the Admiralty's flagship, made his request difficult. Eventually his wooing was successful and the wedding took place on September 2, 1908 in the Royal Chapel of Hampton Court Palace . The following year his only child, Peter Markham Scott, was born, whose godparents were Clements Markham and the author James Barrie , who was friends with Scott .

Conflict with Shackleton (1904-1910)

In the first time after returning from the Discovery expedition , Scott was a guest at numerous events at which he presented the results of the research trip. In November 1904 he gave a lecture in the crowded Royal Albert Hall . His travelogue, published in October 1905 under the title The Voyage of the Discovery , was a literary success, but also a source of continued differences of opinion between him and Ernest Shackleton. According to Scott's account, Shackleton had to be pulled over long distances on the transport sledge due to his poor health on the way back from the march south. However, comparisons with Edward Wilson's records show that this was not true. Scott also condescendingly referred to his third officer as "our invalid " in the book , giving the impression that the rather disappointing southern latitude reached was primarily due to Shackleton and his poor physical condition. Both adversaries chose a reserved and respectful tone in public and in their written correspondence, but according to some biographers Scott's behavior was a deliberate humiliation of Shackleton, whose attitude towards Scott has since been marked by contempt and dislike.

In January 1907, Scott turned to the Royal Geographical Society with plans for another Antarctic expedition. A little later he was surprised by Shackleton's announcement in the London Times of February 12, 1907 that he was going on a research trip to Antarctica that same year. Her aim was to advance to the South Pole for the first time, using the hut of the Discovery Expedition on the Hutpoint Peninsula as a base camp. Scott wrote several letters to Shackleton to assert his supposed prerogative over the McMurdo Sound region . Finally, with the help of Edward Wilson, he succeeded in wresting Shackleton's promise to stay away from McMurdo Sound and instead set up the base camp east of the 170th longitude.

When Scott learned that Shackleton had disregarded the agreement in the course of the Nimrod Expedition (1907-1909), the relationship between the two men was finally broken. Scott berated Shackleton as an "avowed liar" to a representative of the Royal Geographical Society. After Shackleton's return, Scott was reluctant to take part in the welcoming ceremony "as a slave to his sense of duty," as the Royal Geographical Society librarian Hugh Robert Mill (1861–1950) described. Scott used a dinner speech during a reception at the Savage Club in June 1909 for the rival who had narrowly failed on the march to the South Pole to underline his own ambitions. In any case, an Englishman had to be the first to arrive at the Pole and he was ready to “take on this subject.” He added ambiguously: “Now all that remains for me is to thank Mr. Shackleton for letting me know in such a decent manner showed the way. "

Terra Nova Expedition (1910-1913)

Preparations

Although his second Antarctic expedition also had a scientific focus, according to Scott himself the goal was primarily "to reach the South Pole and to secure the glory of this success for the British Empire ." In December 1909 he left his service on half pay leave the Royal Navy free so that they can fully devote themselves to the extensive preparations. Since neither the Royal Geographical Society nor the Royal Society participated in the venture, Scott was dependent on private donors. To raise the required £ 40,000 (about € 4.5 million, adjusted for inflation), Scott lectured and promoted his project nationwide, but with only moderate success. In January 1910 the British government gave him half of the estimated amount. This gave him sufficient funds to acquire the ship Terra Nova , which gave the expedition its name, and to equip it for the research trip.

In the opinion of historian Beau Riffenburgh, Scott's venture “smacked like a Shackleton copy.” During the later march to the South Pole, Scott chose exactly the same route as Shackleton three years earlier. There are countless allusions to Shackleton and comparisons of routes and times in his diary entries. Like his rival on the Nimrod expedition before, Scott opted for a strategy that consisted of dogs, Manchurian ponies, snowmobiles and man-hauling , which, in Fridtjof Nansen's opinion, was just pointless drudgery it was to be avoided at all costs. Even if Scott himself knew nothing about horses, Shackleton's success encouraged him to use animals. His experienced dog specialist Cecil Meares (1877–1937) traveled to Siberia to buy sled dogs. Although Meares had no experience with horses, Scott hired him to buy ponies for the expedition there as well. Meares returned with mostly ailing ponies that were unsuitable for a long stay in Antarctica. Meanwhile, Scott stayed to test the snowmobiles in France and Norway, where he recruited the mechanic Bernard Day (1884-1934), an expert in internal combustion engines, as another member of the expedition. Both Day and the geologist Raymond Priestley , whom Scott also recruited, had previously been participants in the Nimrod expedition under Ernest Shackleton. Shackleton considered neither Day nor Priestley in his later research trips, which is taken as a further indication of the rivalry between him and Scott.

First year in Antarctica

After the Terra Nova had left Cardiff on June 15, 1910, she reached Melbourne on October 12 after a stopover in Simon's Town, South Africa . There Scott left the ship in order to raise further financial support for the expedition, while the Terra-Nova continued her journey to New Zealand. That same evening Scott received a worrying telegram from Madeira . With the short message “ Beg leave to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctic. ”(Freely translated:“ I would like to inform you that the Fram is going on to Antarctica. ”) The Norwegian Roald Amundsen challenged him to the race to the South Pole, completely surprising . According to the author Diana Preston, Amundsen, who is "unscrupulously ambitious", changed his original plans for a North Pole expedition without further ado and without informing the public after the news had gone around the world in September 1909 that the North Pole was already there (supposedly by Frederick Cook or Robert Edwin Peary ). When the press asked him about a reaction to Amundsen's challenge, Scott reiterated that he would not change his original intentions. He will try to get to the South Pole, but not at the expense of the scientific goals of his expedition. On November 29, 1910 , he and his 64-strong team drove south from Port Chalmers in New Zealand with 19 ponies, 33 dogs and three snowmobiles on board the Terra Nova .

The expedition faced considerable difficulties. On the voyage to the Antarctic continent, the Terra Nova initially ran into heavy seas, numerous expedition members suffered from seasickness , the ship threatened to fill up with seawater, and the animals were also affected. On December 7, the first pack ice was encountered far north of the Arctic Circle near Scott Island , which finally held the ship captive for 20 days and damaged the steering gear. As a result, the arrival on Ross Island was delayed , so that there was little time for the preparatory work until the Antarctic winter. During the landing at Cape Evans in January 1911, Scott lost the first snowmobile after it broke through an ice sheet that was too thin and sank into the sea. Bad weather and the ponies that were not adequately adapted to these conditions ultimately also ensured that one of the most important material depots for the South Pole March was built around 59 km further north than originally planned. Scott had rejected the suggestion of Lawrence Oates , who was responsible for the ponies, to kill some of the animals as food and to move the so-called One Ton Depot to a more southern latitude of 80 ° S. Oates is reported to have said to Scott, "Sir, I'm afraid you will regret not taking my advice." Six horses died during the disastrous march back to base camp. After arriving on the Hutpoint Peninsula at the end of February 1911, Scott learned that Amundsen had set up his quarters about 680 km further east in the Bay of the Whales .

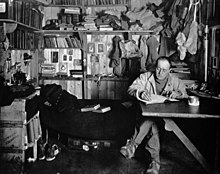

Scott nevertheless refused to change his schedule. “The better and at the same time smarter way for us is to carry on as if nothing had happened.” He was aware that Amundsen's camp was around 110 km closer to the South Pole and that the Norwegians were proven experts in handling sled dogs. However, in contrast to his opponent, he himself had the advantage of wanting to advance to the South Pole via a known route. And so Scott's confidence increased in the course of the winter of 1911. On August 2, after a three-man crew returned from the successful winter march to Cape Crozier , he noted : “I am sure that we are as close to perfection as experience allows. "

March to the South Pole

The march to the South Pole began on November 1, 1911. Scott's entourage consisted of 16 men with snowmobiles, dogs and ponies for the transport of equipment and supplies. Their task was to enable a group of four men to advance to the South Pole. Scott had submitted his plans to the entire landing crew, but without giving any specific assignments. Consequently, none of his companions knew who, besides Scott, would belong to the South Pole Group. In addition, following the descriptions of some expedition members and the description of the majority of Scott's biographers, Scott sent some contradicting instructions to the base camp during the march. Apparently, it remained unclear whether the returning sled dog teams should primarily be spared for later scientific exploratory marches or, in accordance with an order written in advance by Scott, should be used to support the returning South Pole group. In the end, the team at Cape Evans avoided making a targeted advance with the dogs to rescue the distressed South Pole group.

The number of expedition members marching south, who made slow progress due to adverse weather conditions and the early failure of snowmobiles and ponies, gradually decreased because individual support groups returned to base camp as planned. On January 3, 1912, the last two groups of four finally reached a latitude of 87 ° 32 ′ S. Here Scott announced his decision to make five instead of four, along with Edward Wilson , Lawrence Oates , Edgar Evans and Henry Bowers the way to the South Pole to complete while Thomas Crean , William Lashly and Scott's deputy Edward Evans had to give up their hopes and return to Cape Evans.

Scott and his men finally reached the South Pole on January 18th. At the destination they found that Roald Amundsen and four companions had already arrived there five weeks earlier. Scott recorded his desperate disappointment at the defeat in his diary: “The worst has happened […] All [my] dreams are gone […] Great God! this is a terrible place [...]. "

Death on the way back

The emaciated and frostbitten men of the South Pole group set out on January 19, 1912 on the more than 1300 km long return trip to the base camp at Cape Evans. Two days earlier, Scott - already aware of his defeat, but still unaware of Amundsen's lead - had expressed the hope of still being able to dispute the victory for the Norwegians when he noted in his diary: “Now the way home and a desperate fight to get the news [of reaching the South Pole] through first [before Amundsen]. I wonder if we can do it. ”At first, despite the bad weather, they made good progress with freezing temperatures (according to Scott's records these were as low as -30 ° F and -34 ° C ). By February 7, they had already covered 500 km to the upper edge of the Beardmore Glacier in the Transantarctic Mountains and began the 160 km long descent over the glacier to the Ross Ice Shelf . However, Edgar Evans' health had deteriorated rapidly since January 23, according to Scott's notes. After falling into a fissure in the ice on February 4, Evans was "quite numb and incapable." On February 17, Evans fell into a coma after another fall at the foot of the glacier and died that same day, believed to be of a brain injury. Regarding Evans' death, Scott noted: "It is a terrible thing to lose a comrade this way, but on sober consideration, given the terrible worries of the past few weeks, there could have been no better ending."

The remaining four men had more than 660 km to travel across the Ross Ice Shelf, but the prospects continued to deteriorate. Plagued by stormy weather with falling temperatures, severe frostbite, snow blindness, hunger and exhaustion, they only struggled slowly. On March 17th, Lawrence Oates , who was barely able to walk after breaking open an old leg injury and frozen feet, put an end to his life. During a blizzard , he left the tent saying, "I'm just going to go outside and stay there for a while." Scott was already aware at this point that he, Wilson and Bowers would also not survive when he wrote in his diary : “[...] it was the act of a courageous man and an English gentleman . We all hope to face the end with the same attitude, and the end is certainly not far off. "

Scott, Wilson and Bowers struggled another 20 km north until they made their last camp on March 19. This was only 21 km south of the important One Ton Depot , whose originally planned position further south the men had already exceeded by 38 km. However, a persistent blizzard kept them trapped in the tent. During the remaining days, when the remaining food and fuel supplies were running low, Scott made the final entries in his diary. The records end on March 29, 1912 with the words: “Last entry. For God's sake, take care of our people. "

Scott left a series of suicide notes for Edward Wilson's wife, Henry Bowers' mother, some of his friends and superiors in the Royal Navy, and his mother, Hannah, and his wife, Kathleen. He also wrote the "Message to the Public", which was primarily a justification for organizing and leading the expedition and in which Scott blamed the weather conditions and other unfortunate circumstances for the catastrophic failure of his South Pole March. The text ends with a pathetic note typical of Scott :

“We took risks [and] we knew we were taking them; things have turned against us, and so there is no cause for complaint for us to instead submit to fate and fulfill our duty to do our best to the end. […] If we had lived [survived] I would have a story to tell about the boldness, perseverance and courage of my comrades, which would touch the heart of every Englishman. These few lines and our dead bodies [now] have to tell the story, but surely, surely our great and rich fatherland will see to it that those who depend on us are adequately provided for. "

It is believed that Scott was the last of the three men to die on the day of his last journal entry or shortly thereafter. On November 12, 1912, a search party came across the last camp of the South Pole Group. Scott's body was found with an arm wrapped around Wilson. The three dead men were covered with the outer tarpaulin and a high snow hill was built over them, which was flanked by two erected transport sleds and on the top of which stood a wooden cross made of ski boards.

The grave of Scott, Wilson, and Bowers is now under ice and the location is only roughly known. According to calculations by the geophysicist Charles Bentley , the three dead will reach the northern edge of the Ross Ice Shelf around the year 2275 due to the glacier drift and there may be released into the Ross Sea in an iceberg .

aftermath

Immediately before departure from Ross Island, eight members of the expedition, led by Edward Atkinson , erected a wooden memorial cross made by the ship's carpenter on Observation Hill at Hut-Point , in which the names of the five dead and a were placed, between January 20 and 22, 1913 Engraved quote from Alfred Tennyson's poem Ulysses : "Strive, seek, find and do not give up."

Hero worship

When the Terra Nova arrived in Oamaru , New Zealand on February 10, 1913 , news of the death of Scott and his four companions went around the world. Aided by a glorifying nationalism that sprouted in the United Kingdom through the increasing loss of power of the British Empire in the years before the First World War , Scott achieved the status of a national hero within a few days. At a memorial service in St. Paul's Cathedral on February 14, London's Evening News called, under the headline “Let us tell the children how English people die”, that Scott's story should be shared in schools across the country. He was also given praise and obeisances in a large number of other British press organs. Herbert Beerbohm Tree , founder of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art , suggested the establishment of a pantheon for Scott and his companions.

The international press often adopted the British style . For example, on the occasion of the publication of the first excerpts from Scott's expedition diary, the New York Times wrote that it was a report "[...] which excites every heart that can be aroused by stories of heroism and suffering [...]."

The London Times was the only British newspaper in those days to find any disproportionate public perception. In an article dated February 13, 1913, in response to the glorifying accounts, it was suggested that both Amundsen and Scott would have been astonished to "hear that such a disaster is capable of overtaking a well-organized expedition . "

Amundsen's achievements took a back seat in the face of posthumous hero worship for Scott. The story of first reaching the South Pole, in the eyes of the public, was primarily the story of Scott, whose emotional rhetoric resonated more than Amundsen's sober account of events in The South Pole . The book Scott's Last Expedition , which is largely based on Scott's expedition diary, became an international bestseller ; Amundsen's victory in the race to the South Pole, on the other hand, was viewed as insidious "unsporting behavior", especially in Scott's homeland. In view of the resentment shown towards him and the enormous popularity of his late British adversary, Amundsen felt compelled to say: "I would be happy to forego fame and money if I could have saved Scott from his terrible death." the President of the Royal Geographical Society, Lord Curzon , showed his disdain for Amundsen, who had returned from the successful South Pole expedition . At a reception in London on November 15, 1912, Curzon exclaimed in a toast : “I almost wished we could include in our appreciative admiration those wonderfully good-natured dogs [...] without which Captain Amundsen could never have reached the Pole . […] Therefore […] three cheers for the dogs. ”This, according to Amundsen's view,“ sparsely veiled insult ”is said to have induced the Norwegian polar explorer to resign from his honorary membership of the Royal Geographical Society.

The surviving members of the expedition were honored on their return with awards, such as the polar medal, and with members of the Royal Navy in the form of promotions. Instead of a planned for Scott knighting his wife were Kathleen rank and privileges of the widow of a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath awarded. In 1922 she married the future Baron Kennet Edward Hilton Young (1879-1960), but was committed to the reputation of her first husband until her death in 1947.

Scott's appeal in the "Message to the Public" to care for the bereaved was well received. A foundation set up under his name raised a total of £ 75,000 in donations. Of that, £ 18,000 went to the Scott family. Among the donors known by name were Masonic lodges , of which the polar explorer had been a member since 1901.

In Great Britain alone, more than 30 memorials, statues and a church window were made for Scott in the following decades. The latter was created at the instigation of Scott's brother-in-law, Pastor Lloyd Harvey Bruce (1868-1924), in St Peter's Church in Binton, Warwickshire . The founding of the Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge University was also a reminder of him. Numerous other monuments have been erected in other parts of the world, including the famous statue in Christchurch , New Zealand , created by his wife Kathleen. In 1948, he was also a cinematic monument in the film Scott's Last Ride with John Mills in the lead role. The Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station , built in 1957, bears his name, as does the New Zealand Scott Base station on Ross Island. The lunar crater Scott , located not far from the southern lunar pole, and one of NASA's two Deep Space 2 probes were named after him. In 1963, Wolfgang Weyrauch processed the fate of Scott and his comrades in the radio play The Green Tent .

Revaluations

Scott's reputation as a national hero who embodied British virtues remained for over 50 years. This changed from 1966 when the Scott biographer Reginald Pound, who was granted insight into Scott's original notes, first uncovered personal misconduct in the polar explorer in his book Scott of the Antarctic . However, Pound also held on to hero worship by attesting Scott "a brilliant mind that could not be subjugated by anything". Over the next ten years, more books appeared, each of which questioned Scott's previous reputation to some extent. The hitherto sharpest criticism was given by David Thomson in his book Scott's Men from 1977. Scott was "at least until shortly before his death" by no means the outstanding personality to whom the press and public had made him. Thomson described Scott's expedition preparations as "haphazard" and "flawed"; his management style lacked the necessary foresight. According to author Max Jones, "Scott's multilayered character was revealed and his methods challenged."

The criticism culminated in the 1979 published double biography Scott and Amundsen , in which Roland Huntford settled with the "heroic bungler". Scott's "message to the public" was only the deceptive self-justification of a man who led himself and his comrades to death. From then on, almost exclusively negative revelations about Scott were published. British writer Francis Spufford, in the face of "crushing evidence of botch-up," concluded that Scott had "doomed his companions and covered his tracks with thrashing phrases." Paul Theroux summarized him as "confused and discouraged [...] a mystery to his men, unprepared." and a non-expert [...] in constant self-presentation. "

The judgments of Scott were largely based on the events of the Terra Nova expedition. The following points of criticism were mainly mentioned:

- Failure to Organize an Effective Transportation Strategy: Scott turned down any advice recommending dogs as irreplaceable draft animals. Instead, he used inadequately tested means of transport such as snowmobiles and ponies, as well as the fact that the men pulled the loads as a fixed part of the calculation, which was extremely exhausting and slowed down the speed of movement.

- Lack of judgment and poor knowledge of human nature: Scott was accused of a certain form of nepotism in the selection of his companions , in which personal preferences were more important than practical skills or physical aptitude.

- Logistics breakdown during the advance to the South Pole: Scott's decision to choose Henry Bowers as an additional companion weakened the South Pole group in terms of the supply of sufficient food and fuel from the start.

- Communication deficits: Scott had issued ambiguous and contradicting orders for the use of the sled dogs, which prevented a rescue of the distressed South Pole group.

- Mismanagement in the expedition leadership: This concerns the construction of the One Ton Depot at a lower latitude than the originally planned southern latitude, the careless endangerment of individual expedition members (namely Wilson and Bowers) through their participation in the risky winter march to Cape Crozier and Scott's insistence on collecting geological samples despite the life-threatening location of the south pole group.

- General character weaknesses: Scott was said to be aloof, egocentric, sentimentality, stubbornness and ignorance.

Scott's loss of popularity was accompanied by an increasing enthusiasm for Ernest Shackleton , which began in the United States and then spread to the UK. Within a few years Scott was overtaken in public by Shackleton. In the BBC- produced show 100 Greatest Britons (in German: The 100 Greatest Britons ) in 2002 Shackleton took 11th place. Scott, on the other hand, only ended up in 54th place.

A renewed evaluation in favor of Scott, which the cultural historian Stephanie Barczewski , who works at Clemson University , described as a "revision of the revisionists ", began with the investigations carried out by climate researcher Susan Solomon in 2001 on the weather conditions on the Ross Ice Shelf from February to March 1912 In her book The Coldest March she attributes the sinking of the South Pole group primarily to the unusually low temperatures for the season, without denying the validity of any part of the criticism of Scott. The Scott biography, published in 2004 by polar explorer Ranulph Fiennes , is an almost unreserved defense that Fiennes dedicated to "the families of the slandered dead." Fiennes was later criticized for the personal attacks on Roland Huntford contained in the biography and the assumption that his experiences as a polar explorer would give him special authority to judge Scotts.

Another biography, written by the historian David Crane of Oxford University , appeared in 2005. According to Barczewski, it is "unencumbered by previous interpretations". According to Crane, the decline in Scott's public image was due to the change in cultural values at the end of the 20th century: “It's not that we perceive him differently from those [his contemporaries]. But we see him the way we involuntarily dislike him. ”According to Barczewski, Crane managed to restore Scott's humanity“ far more than with Fiennes' sharpness or Solomon's data. ”Jasper Rees of the Daily Telegraph chose one in his review of the book metaphorical representation: “According to the current weather report for the Antarctic, Scott has enjoyed the first rays of sunshine in 25 years.” Jonathan Dore, author of the New York Times , disliked this positive assessment: “Despite all the attraction of his book, David Crane delivers none Answers that convincingly relieve Scott of any responsibility for his downfall. "

Another attempt to rehabilitate Scott was made by historian Karen May of the Scott Polar Research Institute in 2012. According to her account, there was only one authoritative instruction from Scott on the use of the sled dogs after returning to base camp, which he wrote before leaving for the South Pole March deposited. May relied on a passage in the book South with Scott by Edward Evans . Scott stated in these instructions to meet the group returning home with the dog teams "around March 1st [1912] at a latitude of 82 ° or 82 ° 30 'south." It was the unwillingness, wrong decisions and insufficient competence to blame some expedition participants (namely Edward Evans, Edward Atkinson , George Simpson (1878-1965) and Apsley Cherry-Garrard ) for not implementing this instruction and thereby preventing the South Pole group from being rescued.

literature

Literature cited

- Roald Amundsen : The South Pole . tape I . John Murray, London 1912 ( Text Archive - Internet Archive ).

- Stephanie Barczewski: Antarctic Destinies . Hambledon Continuum, London 2007, ISBN 978-1-84725-192-3 .

- Apsley Cherry-Garrard : The Worst Journey in the World . tape I . Constable & Co., London 1922 ( Text Archive - Internet Archive ). - Volume II. ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive )

- David Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. A Life of Courage, and Tragedy in the Extreme South . HarperCollins, London 2005, ISBN 0-00-715068-7 .

- Edward RGR Evans : South with Scott . The Echo Library, Teddington 2006, ISBN 1-4068-0123-2 ( books.google.de ).

- Ranulph Fiennes : Captain Scott . Hodder & Stoughton, London 2003, ISBN 0-340-82697-5 .

- Roland Huntford : The Last Place on Earth . Pan Books, London 1985, ISBN 0-330-28816-4 .

- Roland Huntford: Shackleton . Hodder & Stoughton, London 1985, ISBN 0-340-25007-0 .

- Leonard Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition . tape I. . Smith, Elder & Co., London 1914 ( Text Archive - Internet Archive ). - Volume II. ( Text archive - Internet Archive ).

- Max Jones: The Last Great Quest . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2003, ISBN 0-19-280483-9 ( books.google.de ).

- Edward J. Larson : An Empire of Ice . Yale University Press, London 2011, ISBN 0-300-15408-9 ( books.google.de ).

- Clements Markham : The Lands of Silence . University Press, Cambridge 1921 ( Text Archive - Internet Archive ).

- David McGonigal: Antarctica - Secrets of the Southern Continent . Frances Lincoln, London 2009, ISBN 978-0-7112-2980-8 ( books.google.de ).

- Hugh Robert Mill: The Life of Sir Ernest Shackleton . William Heinemann, London 1923 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- Hugh Robert Mill: An Autobiography . Longman, Green & Co., London 1951.

- Reginald Pound: Scott of the Antarctic . Cassell & Company, London 1966.

- Diana Preston: A First Rate Tragedy . Constable & Co., London 1997, ISBN 0-09-479530-4 ( books.google.de ).

- Beau Riffenburgh: Nimrod . Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-8270-0530-2 .

- Robert Falcon Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery . tape I. . Macmillan, London 1905 ( Text Archive - Internet Archive ). - Volume II. ( Text archive - Internet Archive ).

- Robert Falcon Scott: Diaries of Robert Falcon Scott. A Record of the Second Antarctic Expedition 1910–1912 . tape 1 . British Library, London ( bl.uk ).

- Susan Solomon : The Coldest March . Yale University Press, London 2001, ISBN 0-300-08967-8 .

- Francis Spufford: I May Be Some Time: Ice and the English Imagination . Picador, New York 1997, ISBN 0-312-22081-2 ( books.google.de ).

- Paul Theroux : Fresh Air Friend . Mariner Books, New York 2000, ISBN 0-618-03406-4 ( books.google.de ).

- David Thomson: Scott's Men . Allen Lane, London 1977, ISBN 0-7139-1034-8 .

- David M. Wilson: Nimrod Illustrated . Reardon Publishing, Cheltenham 2009, ISBN 1-873877-90-0 .

Supplementary German-language literature

- Ernst Bartsch: Last Voyage: Captain Scott's Diary - Tragedy at the South Pole. 1910-1912 . Edition Erdmann, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-86539-824-6 .

- Sylvia Höfer: Into the icy death. Robert F. Scott's expedition to the South Pole . DVA, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-421-04454-9 .

- Christian Jostmann: The ice and death: Scott, Amundsen and the drama at the South Pole . CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62094-2 .

- Rainer-K. Langner: Duel in the Eternal Ice: Scott and Amundsen or The Conquest of the South Pole . Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-596-19256-4 (first edition: 2001).

- Andreas Venzke: Scott, Amundsen and the price of fame - The conquest of the South Pole . Arena, Würzburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-401-06539-7 .

- Stefan Zweig : The fight for the South Pole . In: Great moments of mankind . 12 historical miniatures . Fischer library, Frankfurt am Main / Hamburg 1964 ( projekt-gutenberg.org ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Robert Falcon Scott in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Robert Falcon Scott in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Robert Falcon Scott , information on coolantarctica.com

- Antarctic Explorers - Robert Falcon Scott , information on southpole.com

- Scott 100 ( June 10, 2011 memento on the Internet Archive ) Plymouth City Council information site.

- “Death cannot be far away.” In: one day , January 17, 2012

Individual evidence

- ^ Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery. Volume I. 1905, p. 24 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ a b Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, pp. 214-215. Recalculations based on Shackleton's photographs and Wilson's drawings indicated that they may have only reached 82 ° 11 ′ S.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 20.

- ^ Robert Falcon Scott , genealogical information on sharedtree.com (accessed October 18, 2011).

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 19: “ […] with a horror of blood and a love of solitude. ”

- ↑ Fiennes: Captain Scott. 2003, p. 17.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 23.

- ↑ Markham: The Lands of Silence. 1921, p. 447 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ intelligence, information, and the charm of his manner ”

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 50.

- ^ A b Huntford: The last place on Earth. 1985, pp. 121-23.

- ↑ a b Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Fiennes: Captain Scott. 2003, p. 21.

- ↑ Fiennes: Captain Scott. 2003, p. 22.

- ↑ Fiennes: Captain Scott. 2003, p. 23.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 59.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 82.

- ↑ Markham: The Land of Silence. 1921, p. 448 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 28.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 90.

- ^ Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery. Volume I. 1905, pp. 178-182 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery. Volume I. 1905, p. 84 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery. Volume I. 1905, p. 147 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery. Volume I. 1905, pp. 135-142 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery. Volume II. 1905, pp. 120–150 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive )

- ^ Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery. Volume II. 1905, p. 188 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Fiennes: Captain Scott. 2003, p. 148.

- ^ Huntford: The Last Place on Earth. 1985, pp. 229-230.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, pp. 392–393: “ dreadfully slipshod ”

- ^ Wilson: Nimrod Illustrated. 2009, p. 9. Scott had specified a latitude of at least 85 ° S as a target.

- ↑ Mill: The Life of Sir Ernest Shackleton. 1923, p. 153 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Riffenburgh: Nimrod. 2006, p. 110.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 205.

- ^ Scott, The Voyage of the Discovery. Volume II. 1905, p. 91 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ total collapse ”.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, pp. 60-67.

- ^ Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery. Volume II. 1905, pp. 260-261 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, pp. 78-79.

- ↑ Jones: The last Great Quest. 2003, p. 71.

- ^ Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery. Volume I. 1905, p. 343 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ no journey ever made with dogs can approach that height of fine conception which is realized when a party of men go forth to face hardship, dangers and difficulties […]. ”

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, pp. 67-68.

- ^ Riffenburgh: Nimrod. 2006, p. 105.

- ^ Huntford: Shackleton. 1985, pp. 114-118.

- ^ A b Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, pp. 80-84.

- ↑ a b Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 309.

- ↑ List of Gold Medal Winners from the Royal Geographic Society , accessed June 17, 2018.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 344.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 94.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 350.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, pp. 362-366.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, pp. 373-374.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 387.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 102.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 322.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, pp. 65-66.

- ↑ a b Riffenburgh: Nimrod. 2006, p. 156.

- ^ Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery. Volume II. 1905, p. 85 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) and p. 90 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ our invalid ”.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 310.

- ^ Huntford: Shackleton. 1985, pp. 143-144.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 87.

- ^ New British Expedition to the South Pole. In: The Times. February 12, 1907, p. 12.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 335.

- ^ Ernest H. Shackleton: A New British Antarctic Expedition . In: The Geographical Journal . tape 29 , no. 3 , January 1907, p. 329-332 , doi : 10.2307 / 1776716 , JSTOR : 1776716 .

- ^ Riffenburgh: Nimrod. 2006, p. 161.

- ^ Huntford: Shackleton. 1985, p. 304: “ professed liar ”., Quoted from a letter dated March 28, 1908, from Robert Falcon Scott to John Scott Keltie (1840-1927), chief geographer of the Royal Geographical Society.

- ↑ Mill: An Autobiography. 1951, p. 148: “ as a slave of his sense of duty ”.

- ^ Riffenburgh: 2006, Nimrod. P. 390.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, pp. 397-399: “ to reach the South Pole, and to secure for the British Empire the honor of this achievement. ”

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 116.

- ↑ Fiennes: Captain Scott. 2003, p. 161.

- ^ Riffenburgh: Nimrod. 2006, p. 394.

- ^ Huntford: The Last Place On Earth. 1985, p. 10.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 107.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 113.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 112.

- ^ Riffenburgh: Nimrod. 2006, p. 399.

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 409.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 127.

- ^ McGonigal: Antarctica - Secrets of the Southern Continent. 2009, p. 312 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 128: “ ruthlessly ambitious ”.

- ↑ Amundsen: The South Pole. Volume I. 1912, pp. 42-45 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 129.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, pp. Xxi – xxiii ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 3 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 4 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 6 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, pp. 7-16 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, pp. 19-76 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, pp. 106-107 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 466: “ Sir, I'm afraid you'll come to regret not taking my advice. ”

- ↑ Cherry-Garrard: The worst Journey in the World. Volume I. 1922, p. 127 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) and pp. 136–154 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 187 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 187 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ The proper, as well as the wiser, course for us is to proceed exactly as though this has not happened. ”

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 369 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ I feel sure we are as near perfection as experience can direct. ”

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 447 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 407 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Cherry-Gerard: The worst Journey in the World. Volume II. 1922, pp. 410-413 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ A b Evans: South with Scott. 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume II. 1914, pp. 298-306 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, pp. 528-529 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 545 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ Decided after summing up all observations that we are 3.5 miles away from the pole […]. "Or" [I] found after summarizing all the results that we are still 3.5 miles away from the Pole [...]. "Scott initially believed, however, that he had already reached the South Pole on January 17, 1912 (Huxley: Scotts Last Expedition, Volume I. 1914, p. 544 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) "The Pol. Yes, but under completely different circumstances than expected." Or " The Pole. Yes, but under very different circumstances than expected. ").

- ↑ National Library of Scotland: Scott's last expedition map , photo from the book Scott's Last Expedition in the 1923 edition on flickr.com (accessed December 13, 2012).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, pp. 543-544 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ The worst has happened […] All the day dreams must go […] Great God! this is an awful place [...]. ”

- ^ Scott: Diaries of Robert Falcon Scott. Volume 2, p. 37 ( bl.uk ), entry from January 17, 1912: “ Now for the run home and a desperate struggle to get the news through first. I wonder if we can do it. ”

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 550 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 562 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 560 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ rather dull and incapable ”

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, pp. 572-573 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 573 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ It is a terrible thing to lose a companion in this way, but calm reflection shows that there could not have been a better ending to the terrible anxiesties of the past weeks. ”

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, pp. 574-580 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 592 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ I am just going outside and may be some time. ”Note: Oates' body was not found by a later search party.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 592 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ […] it was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman. We all hope to meet the end with a similar spirit; and assuredly the end is not far. ”

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 595 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ Last entry. For God's sake look after our people. ”

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, pp. 597-604 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 607 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ We took risks, we knew we took them; things have come out against us, and therefore we have no cause for complaint, but bow to the will of Providence, determined still to do our best to the last. [...] Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions wich would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale, but surely, surely a great rich country like ours will see that those who are dependent on us are properly provided for. ”

- ^ A b Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume I. 1914, p. 596 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume II. 1914, pp. 346-347 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Jack Williams: The heroic Age still lives in Antarctica. In: USA Today . January 16, 2001.

- ^ Huxley: Scott's Last Expedition. Volume II. 1914, pp. 398-399 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) “ To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. ”

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, pp. 1-2.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 230.

- ↑ Jones: The Last Great Quest. 2003, p. 199: “ Let us tell the children how Englishmen can die. ”

- ↑ Jones: The Last Great Quest. 2003, p. 201.

- ↑ [Without name]: Scott's own story of his terrible march to death . (PDF) In: The New York Times . November 23, 1913 (accessed November 15, 2011): “ […] which will thrill every heart which can be thrilled by tales of heroism and suffering […]. ”

- ↑ [Without a name]: The Polar Disaster. Captain Scott's Career. Naval Officer and Explorer. In: The Times. February 13, 1913, p. 10: “ to hear that such a disaster could overtake a well-organized expedition. ”

- ↑ Jones: The Last Great Quest. 2003, pp. 91-92.

- ^ Huntford: The Last Place on Earth. 1985, p. 525: “ I would gladly forgo any honor or money if thereby I could have saved Scott his terrible death. ”

- ↑ Larson: An Empire of Ice. 2011, p. 24: “ I wished almost, that in our tribute of admiration we could include those wonderfully tempered […] dogs […] without whom Captain Amundsen would never have got to the Pole. [...] I therefore propose three cheers for the dogs. ”

- ↑ Larson: An Empire of Ice. 2011, p. 25: “ thinly veiled insult ”.

- ^ Huntford: The Last Place on Earth. 1985, p. 538.

- ↑ Jones: The Last Great Quest. 2003, p. 90.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 231.

- ^ Preston: A First Rate Tragedy. 1997, p. 232.

- ↑ Jones: The Last Great Quest. 2003, pp. 106-108.

- ↑ Jones: The Last Great Quest. 2003, p. 109.

- ^ Robert Falcon Scott ( memento of August 26, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), information on the website of Sir George Cathcart Lodge No. 617 of the Grand Lodge of Scotland (accessed November 16, 2011).

- ↑ Jones: The Last Great Quest. 2003, pp. 295-296.

-

↑ a b [Without a name]: Captain Robert Falcon Scott statue returns to public view. In: The Press , January 14, 2016 (accessed March 8, 2016): The statue fell from its base in the Christchurch earthquake in February 2011 and was badly damaged. Since January 2016 it has been featured in an exhibition at the Canterbury Museum specially dedicated to this earthquake .

Will Harvey: Christchurch's Robert Falcon Scott statue gets base isolation In: The Press , October 6, 2017 (accessed June 10, 2019): The statue was returned to its old location in October 2017 with earthquake security devices. - ↑ Jones: The Last Great Quest. 2003, pp. 287-289.

- ^ Pound: Scott of the Antarctic. 1966, pp. 285-286: “ a splendid sanity that would not be subdued ”.

- ↑ Thomson: Scott's Men. 1977, p. Xiii: “ at least, not until near the end ”.

- ↑ Thomson: Scott's Men. 1977, p. 153: “ haphazard ”.

- ↑ Thomson: Scott's Men. 1977, p. 218: “ flawed ”.

- ↑ Thomson: Scott's Men. 1977, p. 233.

- ↑ Jones: The Last Great Quest. 2003, p. 288 ( books.google.de ) “ Scott's complex personality had been revealed and his methods questioned. ”

- ^ Huntford: The Last Place on Earth. 1985, p. 527: “ heroic bungler ”.

- ^ Spufford: I May Be Some Time: Ice and the English Imagination. 1997, p. 4: “ devastating evidence of bungling ”.

- ^ Spufford: I May Be Some Time: Ice and the English Imagination. 1997, pp. 104-105: “ [Scott] doomed his companions, then covered his tracks with rhetoric. ”

- ^ Theroux: Fresh Air Friends. 2000, p. 379: “ confused and demoralized […] an enigma to his men, unprepared and a bungler […] always self-dramatizing. ”

- ^ Barczewski: Antarctic Destinies. 2007, p. 283.

- ^ Barczewski: Antarctic Destinies. 2007, p. 305: “ a revision of the revisionist view ”.

- ↑ Solomon: The Coldest March. 2001, pp. 309-327.

- ↑ Fiennes: Captain Scott. 2003, foreword: “ To the Families of the Defamed Dead ”.

- ↑ Jonathan Dore: Crucible of Ice. In: The New York Times . December 3, 2006 (accessed November 3, 2011).

- ^ Barczewski: Antarctic Destinies. 2007, p. 307: “ free from the baggage of earlier interpretations ”

- ^ Crane: Scott of the Antarctic. 2005, p. 11: “ It is not that we see him differently from the way they did, but that we see him the same, and instinctively do not like it. ”

- ^ Barczewski: Antarctic Destinies. 2007, p. 308: “ far more effectively than either Fiennes's stridency or Solomon's scientific data. ”

- ↑ Jasper Rees: Ice in our hearts. In: The Telegraph . December 19, 2004 (accessed November 3, 2011): “ In the current Antarctic weather report, Scott is enjoying his first spell in the sun for twenty-five years. ”

- ↑ Jonathan Dore: Crucible of Ice. In: The New York Times . December 3, 2006 (accessed November 3, 2011): “ For all the many attractions of his book, David Crane offers no answers that convincingly exonerate Scott from a significant share of responsibility for his own demise. ”

- ↑ Karen May: Could Captain Scott have been saved? Revisiting Scott's last expedition. In: Polar Record. Volume 49, No. 1, 2013, p. 79: “ meeting the returning party about March 1 in Latitude 82 or 82.30. ”

- ↑ Scott of the Antarctic could have been saved if his orders had been followed, say scientists. In: The Daily Telegraph. December 30, 2012 (accessed April 1, 2015).

Conversion data

- ↑ For this and all following amounts of money, the conversion is carried out using the template: inflation and template: exchange rate .

- ↑ Adjusted for inflation, around EUR 8.2 million.

- ↑ Adjusted for inflation, around 2 million euros.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Scott, Robert Falcon |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British naval officer and polar explorer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 6, 1868 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Devonport near Plymouth, England |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 29, 1912 |

| Place of death | on the Ross Ice Shelf , Antarctica |