Discovery expedition

The British National Antarctic Expedition from 1901 to 1904, better known as the Discovery Expedition , was the first official British expedition to Antarctica since James Clark Ross ' voyage 60 years earlier. It was planned by a committee made up of members of the Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society and was intended to carry out scientific research and geographical exploration in what was then an almost completely untouched continent. With this expedition began the careers of many men who would later become main characters in the "hero age" of Antarctic exploration, including the expedition leader Robert Falcon Scott , Ernest Shackleton , Edward Wilson , Frank Wild , Tom Crean and William Lashly .

The expedition was able to show significant pioneering work and important geographical discoveries, including the discovery of the Edward VII Peninsula as the eastern boundary of the Ross Ice Shelf , the first ascent of a manned balloon in the Antarctic, the wintering for two consecutive years, the first step on the polar plateau and a new record in the closest approach to the geographic South Pole. As a trailblazer for later ventures, the Discovery Expedition is an important event in the history of British Antarctic exploration.

After the men returned home, it was hailed as a success, although the ice-frozen Discovery required an extensive rescue operation and doubts later arose about the quality of some of the scientific records. It was alleged that the expedition failed primarily at mastering the means of transport such as skis and dog sledding, a reputation that would keep British expeditions for many years.

background

predecessor

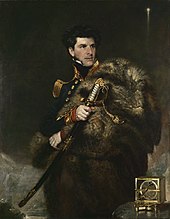

Between 1839 and 1843, Navy Captain James Clark Ross, who commanded the two ships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror , made three trips to Antarctica. During this time he discovered and explored a new area of Antarctica that would become the working area of many subsequent British expeditions, including the Discovery expedition. Ross determined the approximate geography of the region and named many geographic objects, including the Ross Sea , the Ross Ice Shelf later named after him and originally christened the "Great Ice Barrier" , Ross Island , Cape Adare , Victoria Land , McMurdo Sound , Cape Crozier and the twin volcanoes Mount Erebus and Mount Terror . He returned to the Ross Ice Shelf several times, hoping to penetrate deeper, but never succeeded. He reached the southernmost point in February 1842 in a small bay at 78 ° 10 ′ S. Ross suspected that land was to the east of the shelf table, but could not confirm it.

According to Ross, there were no known voyages in this area of Antarctica for fifty years until a Norwegian whaling ship briefly landed at Cape Adare, the northern tip of Victoria Land, in January 1895. Four years later, Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink , who had participated in this landing, undertook his own expedition to the region with the Southern Cross . He landed at Cape Adare in February 1899, built a small hut and spent the winter of 1899 there. The following summer, Borchgrevink sailed south and landed in Ross' bay in the ice shelf. A group of three men then sled to the south on the surface of the ice shelf and came to 78 ° 50 ′ S.

The Discovery Expedition was planned during an increasing international interest in Antarctica around the turn of the century. Four other expeditions were in Antarctica at the same time as the Discovery Expedition: the Gauss expedition under Erich von Drygalski , the Swedish Antarctic Expedition led by Otto Nordenskjöld , another from France under Jean-Baptiste Charcot and the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition under William Speirs Bruce .

Polar exploration was once a traditional Royal Navy activity in peacetime . This interest diminished after the complete loss of the Franklin expedition , which had left Great Britain in 1845 with Ross' ships Erebus and Terror in search of the Northwest Passage and which was never seen again. After the almost fatal north polar expedition from 1874 to 1876 under George Nares , the Admiralty decided that further ventures were dangerous and pointless.

However, the Secretary and later President of the Royal Geographical Society , Sir Clements Markham , a former Navy officer who had served on one of the 1851 expeditions to find Franklin and his men, championed the view that the Navy should resume its historic role. An opportunity to advance this endeavor arose in 1893 when the noted biologist Sir John Murray , who sailed Antarctic waters on the Challenger Expedition in the 1870s , requested a full-fledged Antarctic expedition for the benefit of British science. Both Markham and the Royal Society , the UK's premier scientific body, strongly supported this cause. A joint committee of the two companies was set up to discuss the form of the expedition. Markham's vision of a naval expedition along the lines of Ross or Franklin was critical of parts of the committee, but he was so persistent that the expedition was largely planned according to his ideas. His brother and biographer later wrote that the expedition was "the creation of his brain, the product of his constant energy."

It had long been Markham's practice to look out for promising young naval officers who might later be given prominent roles on a polar expedition, should the opportunity arise. He had first observed midshipman Robert Falcon Scott in 1887 while he was serving with the HMS Rover at St. Kitts , and he remembered him. Thirteen years later, Scott, now a torpedo lieutenant on HMS Majestic , was looking for a way to take the next step in his career, and a chance meeting with Markham in London led him to apply to lead the expedition. Markham had long thought of Scott, even if Scott was by no means always his first choice, but other candidates were either aged or no longer available. With Markham's firm approval, Scott's appointment was resolved until May 25, 1900, soon followed by his promotion to frigate captain .

Science versus adventure

The essence of Scott's area of responsibility still had to be determined. The Royal Society committee members believed that he should only be the captain of the ship that would transport the expedition to Antarctica. They secured the appointment of Dr. JW Gregory, Professor of Geology at the University of Melbourne and former Assistant Geologist at the British Museum , as the scientific leader of the expedition and its leader after the landing. Markham and the faction of the Royal Geographic Society saw things differently. They argued that Scott's command of the expedition must be whole and undivided, and Scott himself insisted on this so much that he threatened to resign. Markham and Scott's view prevailed, and Gregory stepped back, noting that scientific work should not be "subordinate to a naval adventure."

This controversy clouded the relationship between the two societies and lasted beyond the end of the expedition and until the scientific results were published. Markham's insistence on naval command was primarily a matter of tradition and style, rather than an expression of disrespect for science. He himself had expressed his opinion that simply reaching a point further south than anyone before was “not worth the support”.

staff

Though the company was not officially a Navy project, Scott suggested the expedition be conducted the naval fashion and secured the crew's voluntary consent to operate under the Naval Discipline Act . The Admiralty agreed to equip him with three Royal Navy officers and 23 seamen. The remaining members of the expedition should be made up of sailors from the merchant navy or civilians. Two merchant marine officers signed on: Albert Armitage , the first officer, who had gained experience on the Jackson-Harmsworth Arctic expedition from 1894 to 1897, and Ernest Shackleton , who later led expeditions and, together with Scott, became the most important figure in Antarctic exploration in the early 20th century Century should be.

The scientific team was inexperienced. Dr. George Murray, Gregory's successor as chief scientist, was only to travel as far as Australia (in fact, he already left the ship in Cape Town ) and use the voyage to train the scientists, but not take part in the expedition itself. The only scientist with previous Antarctic experience was Louis Bernacchi , who had accompanied Borchgrevink as a magnetologist and meteorologist. The geologist, Hartley Ferrar , was a twenty-two year old graduate from Cambridge University. The marine biologist Thomas Hodgson from the Museum of Plymouth was a little older and more mature, as was Reginald Koettlitz , the elder of two doctors and, at 40, the oldest participant in the expedition. Like Armitage, he had taken part in the Jackson-Harmsworth expedition. The zoologist and younger doctor was Edward Wilson , in whom Scott found a devoted follower. He possessed the calm, the patience, and the distance that Scott allegedly lacked.

Scott was lucky that among the non-officers there were reliable men like Frank Wild and William Lashly , or Thomas Crean , who stepped in after the desertion of the seaman Harry Baker at Lyttelton harbor . Boatswain Edgar Evans and Able Seaman Thomas Williamson would later accompany Scott on his Terra Nova expedition with Lashly and Crean . Another newcomer to Antarctica, later best known in connection with Shackleton, was Ernest Joyce .

Organization and goals

financing

The total cost of the expedition is estimated at £ 90,000 (approximately € 5.7 million in 2008), of which £ 45,000 was provided by the UK Government, provided the two companies were able to raise a sufficient amount. They achieved this largely thanks to a gift of £ 25,000 from Sir Llewellyn Longstaff, a wealthy member of the Royal Geographical Society. The RGS themselves contributed £ 8,000, their largest single contribution to an expedition to date. Another £ 5,000 came from Alfred Harmsworth , later Lord Northcliffe. The remaining amount was made up of smaller donations. The expedition also benefited from commercial sponsorship: Colman's provided mustard and flour free of charge, Cadbury’s gave over 1,600 kilograms of chocolate, Bird's donated pudding and baking powder, and Evans Lescher & Webb donated all of the lime juice needs. Jaeger's gave 40% off specialty clothing, Bovril supplied beef extract and others donated smaller amounts of goods.

ship

The expedition ship was built by the Dundee Shipbuilders' Company as a research vessel and was designed for work in Antarctic waters. The Discovery was one of the last wooden three-masters to be built in Britain. The cost of construction was £ 34,050 plus £ 10,322 for the machines, and the final cost after all the changes were £ 51,000. The name was chosen based on one of the ships of George Nares ' expedition, certain features of the older ship were also taken over into the design of the newer one. She was launched on March 21, 1901 by Lady Markham as the SS Discovery (she was named "Royal Research Ship" in the 1920s).

aims

The Discovery Expedition, like the Ross and Borchgrevink expeditions, was supposed to work in the Ross Sea. Other areas had been considered, but the principle followed that one should start with the known in order to get to the unknown. The main objectives of the expedition were summarized in the instructions of the committee to Commander Scott as follows: "To determine as much as possible the nature, condition and extent of the area of the south polar lands which falls within the scope of your expedition", "Magnetological research to undertake meteorological, oceanographic, geological, biological and physical studies and research in the southern regions in the south of the 40th parallel. The instructions also stipulated that "none of these goals may be sacrificed to the other."

The instructions on the geographic destination were further elaborated: “The main points of geographic interest are […] to explore Sir James Ross's ice barrier towards the east end; To discover the land flanking the barrier to the east, as Ross believed, or to make sure that it does not exist […] if you should decide to hibernate in the ice […], your geographic exploration efforts should be increased […] Direct an advance into the western mountains, an advance south and an exploration of the volcanic region ”.

expedition

The first year

The Discovery left British waters on August 6, 1901 and arrived in New Zealand via Cape Town on November 29, after making a detour to over 40 ° S for magnetological studies. After three weeks of final preparations, she was ready to start the journey south. On December 21st, as the ship left Lyttelton harbor to the cheers of the crowd, an unfortunate accident occurred that cast a shadow over the beginning of the expedition: the young fully qualified seaman Charles Bonner fell from the top of the main mast he was climbing had to return the applause from the crowd and died in the process. He was buried two days later in Port Chalmers .

After the funeral, the Discovery finally set out south and arrived at Cape Adare on January 9, 1902 . After a brief landing, she continued south, along the Victoria coast to McMurdo Bay, and then turned east to land again at Cape Crozier . As agreed, the expedition members left a news station here. The ship then followed the Ross Ice Shelf to its eastern foothills, where the Ross suspected land was confirmed on January 30 and named Edward VII Land .

On February 4, Scott landed on the ice shelf and had an observation balloon brought ashore that he had acquired for aerial exploration. Scott quickly reached a height of over 184 meters with the carefully moored balloon, Shackleton later followed with a second ascent. All they could see was the endless ice surface. Edward Wilson thought the balloon ascents were "sheer madness"; the experiment was not repeated.

The Discovery now turned west in search of a suitable place for winter storage . She entered McMurdo Bay on February 8 and was later anchored near its southern end, later named Winter Quarters Bay . The work on land began with the construction of the expedition hut on a rocky peninsula called Hut Point . Scott had decided that the expedition members should continue to live and work on board the ship, so he had the Discovery freeze in the pack ice and the men use the hut as a storage shed and shelter.

The process of getting used to the new environment was sobering for the Discovery men . Neither man was a skilled skier, and only Bernacchi and Armitage had some experience with dog sledding. The results of initial efforts to master these techniques were not encouraging, and confirmed Scott's prejudice in favor of male pulling the sledges. The dangers for inexperienced travelers in unpredictable and unknown conditions were confirmed when a group returning from a canceled trip to Cape Crozier was trapped on an icy slope during a snow storm on March 11. In an attempt to find safer ground, able seaman George Vince slipped over the edge of a cliff and was killed. His body was never found; a cross with a simple inscription, erected in his memory, still stands on the highest point of the Hut Point peninsula.

During the southern winter from May to August, scientists were busy in their laboratories, while equipment and goods for the next season's work were being prepared elsewhere. For relaxation, there were amateur theater performances and educational events in the form of readings. A newspaper, the South Polar Times , was printed. Outdoor activities have not ceased entirely; the men played soccer on the ice and the planned magnetological and meteorological observations were all carried out.

As winter ended, sleigh rides resumed to test equipment and rations for the proposed trip south that Scott, Wilson and Shackleton would take. In the meantime, a group led by Lieutenant Charles Royds traveled to Cape Crozier to leave a message at the station and discovered the emperor penguin colony, while another team led by Armitage advanced into the mountains to the west for reconnaissance purposes. This team returned in October with symptoms of scurvy . The diet of the expedition members was quickly changed; Canned meat was replaced by fresh meat and the problem was reduced. It is not clear to what extent this change in diet was carried over to the rations carried on the sleigh rides, but it was obviously not enough to prevent the recurrence of scurvy on the southern trip.

Scott, Wilson, and Shackleton left on November 2, 1902 with the dogs and supportive men. Their goal was "to go as far south as we can on the ice of the barrier in a straight line, to reach the Pole if possible, or to find new land". Her lack of control of the dogs soon became apparent, however, and progress was slow. After the support groups turned back, the men switched to moving the equipment on in multiple journeys, and had to travel three kilometers south for every kilometer of effective advance. Mistakes had been made with dog food, and a mixture of poor diet and incompetent treatment further weakened the dogs until Wilson was forced to kill the weakest for food for the rest. The men also had problems, snow blindness, frostbite and possibly scurvy in the early stages afflicted them, but until December 30th they drove further south parallel to the mountains in the west than they did at 82 ° 17 without leaving the ice ′ S reached the southernmost point of their journey, setting a new southern record. On the return trip the difficulties increased as the remaining dogs died and Shackleton collapsed, weakened by scurvy. Scott and Wilson fought on while Shackleton couldn't pull a sled and walked alongside the others or was pulled on the sled. The group finally reached the ship on February 3, 1903 after a journey of 93 days at a disappointingly low speed averaging less than 14 kilometers per day. Yet despite their hardships, they had never stopped mapping the mountain range to the west, identifying and naming numerous geographic objects and landmarks.

Arrival of the supply ship

While the southern group was away, the supply ship Morning had arrived and brought fresh supplies. The organizers of the expedition suspected that the Discovery would clear the ice in early 1903. Scott could then do more research from the sea, move out of the pack ice before winter, and return to New Zealand in March or April. It was planned that the Discovery would sail back to Great Britain through the Pacific Ocean and continue magnetological research en route. The morning should provide whatever assistance Scott could ask for during this time.

This plan was thwarted when the Discovery was frozen solid in the ice. Markham had feared this for himself, and the Morning's captain , William Colbeck, had a secret letter for Scott with him that allowed him another year on the ice. Since the Discovery could not be released, this option became inevitable. The morning was also an opportunity for some of the crew to return to the UK, including, against his will, the convalescent Shackleton, who, according to Scott, "shouldn't risk any further effort in his current health." Some Antarctic historians attribute the antipathy between Scott and Shackleton to this point, while others see it as a by-product of the southern voyage. Still, there is ample evidence that their relationship remained cordial for several years. The Morning left for New Zealand on March 2, 1903, and the men remaining in Antarctica were preparing for another winter.

Second year in the ice

After the winter of 1903 was over, Scott prepared for the expedition's second main voyage, which would include an ascent into the western mountains and an exploration of central Victoria Land. Last year Armitage's reconnaissance team had paved a route to an altitude of 2,670 meters before reversing, but Scott wanted to go further west from there and, if possible, reach the southern pole of the Earth's magnetic field ( Antarctic magnetic pole ). After a false start due to a defective sled, a group of nine men left the Discovery on October 26, 1903 , including Scott, Lashly and Edgar Evans. After climbing a large glacier named after the geologist from the Ferrar Glaciers group , they reached an altitude of 2,100 meters before being held in tents by snowstorms for a week. They only reached the top of the glacier on November 13th. They left Armitage's turning point behind, discovered the polar plateau and were the first to travel through it. After the return of the geological and support crews, Scott, Lashly and Evans drove further west across the monotonous plain for eight more days, reaching the westernmost point of their journey on November 30, just after 148 degrees east longitude and about 112 kilometers southwest of the calculated position of the magnetic pole. Since they had lost their navigation tables in a storm during the ascent of the glacier, they did not know exactly where they were, and due to the monotonous landscape they had no landmarks to help them determine their position. The 240 kilometers return trip to the Ferrar Glacier was very dangerous, but they found the top of the glacier and made a short detour on the descent to discover the rare phenomenon of a snow-free area in Antarctica, the McMurdo dry valleys . Scott and Evans survived a fall into a crevasse that could have been fatal before the group reached Discovery on December 24th . Her average progress on this human-only journey was significantly better than what had been achieved on the previous season's southern journey with dogs, a fact that further reinforced Scott's prejudices against dogs.

Several more trips were made during Scott's absence. Royds and Bernacchi sailed the ice shelf in a southeasterly direction for 31 days, found that its surface was consistently flat, and made further magnetological measurements. Another group had explored the Koettlitz Glacier to the southwest, and Wilson had gone to Cape Crozier to see the emperor penguin colony up close.

Rescue expedition

Scott had hoped to find the Discovery ice-free on his return, but the ice never cracked. Rescue attempts with ice saws had begun, but after 12 days only two parallel cuts of 137 meters had been made while the ship was still 32 kilometers from open water. The work was stopped.

On January 5, 1904, the Morning returned with a second ship, the Terra Nova . It brought with it clear instructions from the Admiralty: If the Discovery could not be freed, it should be abandoned and its crew brought home on the two rescue ships. This ultimatum resulted from Markham's dependence on the Treasury Department to pay for the cost of the rescue expedition, which again had its own terms. The deadline on which the three masters agreed ended on February 25th. A race against time began for the rescue ships trying to catch the Discovery , which was still frozen off the Hut Point Peninsula. As a precaution, Scott began moving his scientific samples to the other ships. Explosives were used to break up the ice and the sawing crews resumed their work, but although the rescue ships were able to approach the Discovery , it remained stuck in the ice, two miles from the open fairway, until late January. On February 10, Scott accepted that he would soon have to begin preparations for the evacuation, but on February 14 the ice suddenly broke and the Morning and Terra Nova were able to navigate the fairway together. A final explosive charge removed the remaining ice on February 16, and the following day the Discovery began its return journey to New Zealand after a last moment of shock when it ran aground on a shoal.

Follow-up time and successes

On their return to Great Britain in September 1904, the expedition was welcomed benevolently. Scott was promoted to Captain of the Royal Navy and invited to Balmoral to meet the King who promoted him to Commander of the Royal Victorian Order . He also received several medals and awards from overseas, including the French Legion of Honor . Other officers and crew members were also promoted. Scott's published report, The Voyage of the Discovery , sold well and gained some notoriety before resuming his naval career, during which he initially served as Assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence and from August 1906 as Flag Captain to Rear Admiral George Egerton ( 1852–1940) served on HMS Victorious .

The most important geographical results of the expedition were the discovery of the Edward VII Peninsula and the ascent to the western mountains, the discovery of the polar plateau, the first sleigh ride on the plateau and the western record beyond the 148th degree of longitude and the journey on the Ross Ice Shelf except for 82 ° 17 ′ S, where a new southern record was set. The nature on Ross Island was described, the chain of the Transantarctic Mountains mapped up to 83 ° S and the position and height of over 200 mountains calculated. Many other geographic objects and landmarks have been identified and named, and extensive survey work has been done on the coast.

In addition to the mass of data from meteorological and magnetological observations that would take years to analyze, some discoveries of great scientific importance were made. These included the snow-free McMurdo dry valleys, the emperor penguin colony at Cape Crozier, scientific evidence that the Ross Ice Shelf is a floating shelf and the fossil leaf that Ferrar found that helped relate Antarctica to the supercontinent of Gondwana . Thousands of geological and biological samples had been collected, from which new marine species could be identified. In addition, the location of the south magnetic pole had been calculated with an acceptable accuracy. However, when the meteorological data were published, their accuracy was controversial among scientists, such as the President of the Physical Society of London, Charles Chree (1860-1928). Scott defended his people's work while privately admitting that Royds' records in the area were "horribly sloppy".

aftermath

The expedition generated considerable enthusiasm among some of its members for future exploration of Antarctica. Scott himself had further ambitions, and three of his officers - Armitage, Barne, and Shackleton - would later have their own agenda. From the members of the team, Frank Wild and Ernest Joyce came back several times to the Antarctic on later expeditions. With a total of five ventures, Wild participated in more expeditions than any other researcher.

The expedition was largely presented to the public as a national success, thanks in part to the enthusiasm of Markham. Scott, in particular, became a hero. However, this euphoria was anything but conducive to an objective analysis or a considered weighing of the strengths and weaknesses of the expedition. As a result, characteristics such as reliance on courage and imaginative improvisation were seen as the norm by later British expeditions rather than professionalism. In particular, Scott's glorification of men hauling sleds as something more classy in itself than other ways of getting around on the ice led to a general distrust of methods involving skis or dogs.

Scott applied some of the lessons learned on the Discovery Expedition to his next venture, the Terra Nova Expedition . He took a larger and more experienced scientific team with him, he avoided freezing his ship in the ice, he hired a ski expert and let his men gain experience in skiing. However, he repeated the general form of the earlier expedition - its size, multiple destinations, and formal naval character; and above all he retained his prejudices against dogs, at least until it was too late to influence the outcome of the expedition (see Terra Nova Expedition). Shackleton's 1907-1909 Nimrod Expedition , which was smaller, less formal and had a more well-defined destination, far surpassed Scott's exploration success and nearly reached the Pole. However, Shackleton's transport system was not based on dogs, but on Siberian ponies, so that Scott's bad opinion of the dogs was not influenced, and Shackleton's impressive results might even intensify it.

The fact that it was not possible to avoid the scurvy , which also became a problem on the following expeditions, is more likely to be attributed to medical ignorance regarding the reasons for the disease than to the expedition leader. At the time, it was known that a diet based on fresh meat could have healing effects. Fresh seal meat was taken with us on the southern voyage “in case we find ourselves attacked by scurvy”, a choice of words that suggests that the meat was intended for post-disease treatment rather than preventative use. It is not known how much fresh meat was taken, but the scurvy occurred during the trip. On his Nimrod expedition, Shackleton avoided the disease by carefully selecting foods that included additional penguin and seal meat. However, Lieutenant Edward Evans nearly died during the Terra Nova expedition, and scurvy also spread in the Ross Sea Party from 1915 to 1916. It remained a threat until its causes were finally revealed, some 25 years after the Discovery Expedition.

See also

Literature and Sources

- EC Coleman: The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration, from Frobisher to Ross . Tempus Publishing, 2006, ISBN 0-7524-3660-0 .

- David Crane: Scott of the Antarctic . HarperCollins, 2005, ISBN 0-00-715068-7 .

- Ranulph Fiennes : Captain Scott . Hodder & Stoughton, 2003, ISBN 0-340-82697-5 .

- Roland Huntford : The Last Place On Earth . Pan edition, 1985, ISBN 0-330-28816-4 .

- Max Jones: The Last Great Quest . OUP, 2003, ISBN 0-19-280483-9 .

- Diana Preston: A First-Rate Tragedy . Constable-Paperback, 1999, ISBN 0-09-479530-4 .

- Ann Savors: The Voyages of the Discovery: Illustrated History . Chatham Publishing, 2001, ISBN 1-86176-149-X .

- Robert Falcon Scott: The Voyage of the Discovery . Vol. 1, Smith, Elder & Co, 1905

- Michael Smith: To Unsung Hero: Tom Crean, Antarctic Survivor . Headline Book Publishing, 2000, ISBN 1-903464-09-9 .

- Edward Wilson: Diary of the Discovery Expedition . Ed. Ann Savors, Blandford Press-Edition, 1966, ISBN 0-7137-0431-4 .

Additional literature

- Roland Huntford : Shackleton . Hodder & Stoughton, 1985, ISBN 0-340-25007-0 .

- M. Landis: Antarctica: Exploring the Extreme: 400 Years of Adventure . Chicago Review Press, 2003, ISBN 1-55652-480-3 .

- George Seaver: Edward Wilson of the Antarctic . John Murray, 1933

- JV Skelton & DW Wilson: Discovery Illustrated: Pictures from Captain Scott's First Antarctic Expedition . Reardon Publishing, 2001, ISBN 1-873877-48-X .

- Judy Skelton (Ed.): The Antarctic Journals of Reginald Skelton: 'Another Little Job for the Tinker' . Reardon Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1-873877-68-4 .

Web links

Notes and individual references

- ^ Huntford, p. 188

- ↑ Coleman, pp. 329-335

- ^ Preston, pp. 12-14

- ↑ Scott's instructions as leader of the Discovery Expedition instructed him to "discover the land that the barrier is supposed to flank to the east as assumed by Ross". Savors, pp. 16-17

- ↑ This landing was claimed to be the first landing on the Antarctic continent. The American John Davis probably landed on the Antarctic Peninsula as early as 1821: see Beau Riffenbaugh: Nimrod , Bloomsbury 2005, p. 36

- ↑ This expedition was funded by a donation of £ 35,000 from British publishing magnate Sir George Newnes (1851-1910) - Preston, p. 14. A condition of this donation was that the company should be called the British Antarctic Expedition, too when it didn't get official recognition and only two of the ten men in the coastal group were British.

- ↑ Some historians give a slightly different width

- ↑ Crane, p. 67

- ^ Crane, p. 2

- ↑ Max Jones, p. 50

- ^ Preston, p. 15

- ↑ Murray had been the assistant to the Challenger's chief scientist , Charles Wyville Thomson , and after his death in 1882 took over responsibility for the production of the scientific reports

- ↑ Max Jones, pp. 56-57

- ↑ Max Jones, p. 58

- ↑ Crane, pp. 82-83

- ↑ Preston, pp. 28-29

- ↑ Crane, pp. 91-101

- ^ Crane, p. 91

- ↑ Max Jones, pp. 62-63

- ↑ Max Jones p. 63

- ↑ Fiennes, p. 35

- ↑ The list of expedition members as listed by Ann Savors, p. 19, lists 27 men from the Navy, two marines, five merchant navy seamen and three civilians, excluding officers and scientists. However, this list includes substitutes.

- ↑ As Scott's reputation deteriorated in the late 20th century, Shackleton's reputation rose. When the BBC called on viewers to vote for the greatest Britons of all time in 2002, Shackleton came in 11th, Scott just 54th - Max Jones, p. 289

- ↑ Fiennes, pp. 43-44

- ↑ Markham described Ferrar as "very immature and quite lazy" but "could be made into a man." Preston, p. 36

- ^ Preston, p. 222

- ^ Huntford, p. 160

- ↑ Michael Smith, p. 31

- ↑ Joyce was a major participant in Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition from 1907 to 1909 and also part of the Ross Sea Party , which supported Shackleton's Expedition Endurance from 1914 to 1917.

- ↑ Modern equivalents of 1901 costs are not easy to calculate. The lists used are those of Fiennes for 2003 with a slight surcharge. They were also converted into euros using the exchange rate of March 28, 2008. See Fiennes, pp. 33-34

- ↑ Harmsworth had previously financed the Jackson Harmsworth Expedition to the Arctic

- ^ Preston, p. 39

- ↑ Savors, pp. 11-18

- ↑ Savors, p. 15

- ↑ Savors, p. 18

- ↑ Fiennes, p. 31

- ↑ Savors, pp. 16-17

- ↑ Savors, p. 16

- ↑ Savors, p. 24

- ↑ Michael Smith, p. 37

- ↑ That McMurdo was more of a sound than a bay was only discovered later during the expedition

- ↑ News stations were set up at predetermined locations so that rescue ships could find the expedition if necessary

- ↑ The name "Edward VII Land", today "Edward VII Peninsula", today only refers to a small peninsula that borders the Ross Ice Shelf, but not the large land masses in the south and east

- ↑ Preston, pp. 45-46.

- ^ Wilson's diary entry, February 4, 1902, p. 111

- ↑ Because of its location near the edge of the ice shelf, the hut was used as a shelter and storage hut on all subsequent expeditions in this sector

- ↑ See Scott's Voyage of the Discovery , Vol. I, p. 467, for Scott's much-quoted statement about the superiority of human sleigh pulling

- ↑ Michael Smith, p. 51

- ↑ Crane, pp. 175-185

- ^ Fiennes, p. 87

- ^ Preston, p. 59

- ↑ See Crane, pp. 194–196, for a report on the scurvy incident

- ^ Wilson's diary, January 14-18, 1903, pp. 238-239

- ^ Wilson, diary entry June 12, 1902

- ^ Crane, p. 205

- ↑ Although most instances, including Scott, Wilson and Shackleton, state 82 ° 17 ′ as the southern record, others such as Fiennes and Crane cite 82 ° 11 ′ as the turning point. In addition, Crane claims (pp. 214–215) that modern position calculations settled the location between 82 ° 05 'and 82 ° 06'

- ^ Crane, pp. 226-227. Wilson's diary evades the question of scurvy and only mentions (on January 14, 1903) that "we all have mild but obvious signs of scurvy."

- ↑ The extent to which Shackleton was drawn is portrayed differently in Scott and Shackleton's accounts, while Wilson tends to endorse Shackleton

- ^ Crane, p. 233

- ^ Crane, p. 273

- ↑ Colbeck had been on the Southern Cross with Borchgrevink and had taken part in the short trip over the barrier that set Borchgrevink's southern record of 1900. Cape Colbeck in Edward VII Land was named after him

- ^ Crane, p. 233

- ^ Preston, p. 68

- ↑ See Fiennes, p. 100

- ↑ The transferred words and deeds of Scott and Shackleton do not support the view that there was bad blood between them before Shackleton became a rival to Scott in the race for the South Pole. Albert Armitage, who fell out with Scott, was the main source of stories of a break between Scott and Shackleton. On the other hand, the tone of Shackleton's letter to Scott to welcome him home in September 1904, see Crane p. 310, indicates an unbroken mutual respect at the time.

- ^ Preston, p. 68

- ↑ Lashly's alleged comment on the dry valleys was "a good place to plant potatoes" - Crane, p. 270

- ↑ Crane, p. 270, calls the trip to the west "one of the great trips in polar history"

- ↑ Preston, pp. 76-77

- ^ Crane, p. 275

- ↑ Fiennes, pp. 129-130

- ↑ Michael Smith, p. 66

- ↑ Crane, pp. 277-287

- ↑ Scott had been made a member of the Royal Victorian Order in 1901 when the Discovery left Cowes .

- ^ Crane, p. 309

- ^ Crane, p. 322

- ↑ A flag captain is the captain of an admiral's flagship

- ^ Crane, p. 325

- ^ Preston, p. 47

- ^ Wilson's diary, December 30, 1902, p. 230

- ^ Preston, p. 77

- ↑ Crane, pp. 272-273

- ^ Crane, p. 272

- ↑ Huntford, pp. 229-230

- ^ Crane, p. 392

- ↑ Max Jones, p. 72

- ↑ Only Shackleton's plans were ultimately implemented.

- ^ Crane, p. 303

- ↑ Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition from 1907 to 1909, for example, had strong individual figures, but hardly more Antarctic or Arctic experience than the Discovery had.

- ↑ Max Jones, p. 71

- ↑ See Huntford, pp. 138-139 and Max Jones, p. 83

- ↑ Shackleton's idea convinced Scott to take ponies with him on the Terra Nova expedition and use them as the main element in his complex transport system. In fact, he only bought white ponies, as Shackleton had observed that the darker colored ponies had died before the lighter colored ones. - Preston, p. 113

- ^ Preston, p. 219

- ^ Wilson's diary entry from October 15, 1902

- ↑ See Beau Riffenburgh's History of the Nimrod Expedition, pp. 190–191 ( Nimrod , Bloomsbury Paperback Edition 2004, ISBN 0-7475-7253-4 .)

- ^ Huntford, p. 163