Erich von Drygalski

Erich Dagobert von Drygalski (born February 9, 1865 in Königsberg , † January 10, 1949 in Munich ) was a German geographer , geophysicist , geodesist and polar researcher . He led the Greenland Expedition of the Society for Geography in Berlin (1891-1893) and the Gauss Expedition (1901-1903), the first German expedition to the Antarctic.

Life

Erich von Drygalski was born as the son of the director of the Kneiphöfisches Gymnasium in Königsberg, Fridolin von Drygalski (1829–1904), and his wife Lydia (née Siegfried, 1838–1913). He attended the Kneiphöfische Gymnasium. At the age of 17 he began studying mathematics and physics at the Albertus University in Königsberg in 1882 . After just one semester, he switched to geography at the University of Bonn to hear Ferdinand von Richthofen's lectures . He followed his teacher to the universities of Leipzig and Berlin . He completed his studies in 1887 with the dissertation "The Geoid Deformation of the Ice Age" , a study of the ice cover of Nordic regions. Between 1887 and 1891 he was an assistant at the Geodetic Institute and the central office for international geodetic surveying in Berlin.

From 1891 and 1892/1893 Drygalski led two expeditions to West Greenland , equipped by the Berlin Geography Society , which attracted a great deal of attention. With the results of his research he qualified as a professor in geography and geophysics in 1898, and in the same year he was appointed head of the first German Antarctic expedition by the “German Commission for South Polar Research” . In 1898 he became a lecturer and in 1899 associate professor for geography and geophysics in Berlin. From 1901 to 1903 Drygalski led the first German south polar expedition, the Gauss expedition . In 1906 he followed a call to Munich, where he accepted a professorship for geography and geophysics and held it until his retirement ; in the same year he was elected a member of the Leopoldina . There he was also a member of the Geographical Society . He founded the Institute of Geography and was its director until his death.

Drygalski married in 1907 and had four daughters. In 1910 von Drygalski took part in a study trip to Spitzbergen under the direction of Graf Zeppelin , the aim of which was to examine the suitability of airships in the Arctic. From 1909 Erich von Drygalski was an extraordinary member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences , in 1912 he was elected a full member. In 1935 he retired. Erich von Drygalski died on January 10, 1949 in Munich . His grave is in the Partenkirchen cemetery .

Today a street in the south of Munich, Drygalski-Allee, and an archive in Munich's Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität are a reminder of his academic achievements. Drygalskistraße in Berlin-Dahlem in the Steglitz-Zehlendorf district has had his name since around 1910.

First German Antarctic expedition

From 1901 to 1903 the Gauss expedition took place under the leadership of Drygalski , the first German research trip to the Antarctic. The 32 participants, including five scientists (in addition to Drygalski: Friedrich Bidlingmaier (1875–1914, geomagnetics and meteorology), Hans Gazert (1870–1961, medical and bacteriological work), Emil Philippi (1871–1910, geological and chemical studies), Ernst Vanhöffen (1858–1918, botany and zoology), went on board the Gauß , a research ship that was built especially for this expedition. Contrary to common usage, the ship was called the Gauss .

On August 11, 1901, the expedition set sail from Kiel and reached Cape Town on November 22, at the southern tip of Africa. The journey continued on December 7th, and unknown land was sighted for the first time on February 21st, 1902. It was named Kaiser-Wilhelm-II.-Land after the German Kaiser . The very next day the ship hit solid ice, which made further progress very difficult. A little later, on March 1st, the ship was finally locked in by the ice and held about 50 miles offshore for almost a year. Due to the rounded shape of the hull (similar to that of the Norwegian polar research ship Fram ), the ship was not crushed by the ice, but lifted.

The period of forced immobility was used for intensive research activities. Much meteorological and zoological data and observations were collected, which later filled a 22-volume expedition report. Seven journeys into the area were made with sledges, and with the help of a hydrogen- filled balloon , the wider area could also be observed. In three ascents on March 29th with Drygalski on board, the balloon reached a height of about 500 meters. A dark elevation was sighted near the coast and was the destination of an exploration trip. The scientists discovered an extinct volcano about 80 kilometers away , which they named " Gaußberg ", and measured its height at 371 meters.

Since the ice did not release the enclosed ship in the Antarctic spring of the following year, the crew scattered ash several times in the area between the Gauss and the ice edge. The dark ash layer, absorbing the sunlight, melted a fairway two meters deep into the ice. The Gauss was released on February 8, 1903 and reached the open water again on March 16. A second hibernation was not possible and therefore no further advance south. So Drygalski ordered a north course, and on June 9 the Gauss returned to Cape Town. Since the German government did not approve the funds for a further winter, the expedition started the journey home and reached Kiel on November 23, 1903.

On the Kerguelen , parallel to the main expedition, a geomagnetic and meteorological observation station worked in the Baie de l'Observatoire ("observation bay"). This collected comparative data for the observations made on the Gauss . The group working there consisted of the scientists Josef Enzensperger (meteorologist), Karl Luyken (geomagnetic) and Emil Werth (botanist), as well as the sailors Urbansky and Wienke.

The Gauss expedition brought science numerous new discoveries about a previously almost unexplored region of the world and was therefore a great scientific success overall. Kaiser Wilhelm II was dissatisfied, however, because the German expedition only advanced to 66 ° 2 'south latitude, while the British expedition had reached 82 ° 17' south latitude. However, Drygalski did not want to take part in a “race to the pole” after his return. He is said to have said to his employees: "For polar research , it is irrelevant who is first at the pole". The Gauss was later sold to Québec , Canada and used for a North Pole trip .

Drygalski as namesake

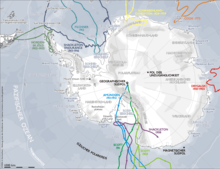

Several geographic objects and a lunar crater are named after Drygalski:

- the Drygalski ice tongue ( 75 ° 24 ′ S , 163 ° 30 ′ E ), named by the British polar explorer Robert Falcon Scott , leader of the Discovery Expedition , which was doing research in Antarctica at the same time as Drygalski

- the Drygalski Basin ( 74 ° 50 ′ S , 169 ° 25 ′ E ), named after the nearby Drygalski ice tongue

- the Drygalski Glacier ( 64 ° 43 ′ S , 60 ° 44 ′ W ) in Grahamland, named by Otto Nordenskjöld , head of the Swedish Antarctic Expedition , which took place at the same time as Drygalski's expedition

- the Drygalski glacier ( 3 ° 3 ′ S , 37 ° 21 ′ E ) on Kilimanjaro , named by the Africa explorer Hans Meyer

- the Drygalski Mountains in Queen Maud Land was created by participants in the (third) German Antarctic Expedition 1938/39 named

- the Drygalski Fjord ( 54 ° 48 ′ S , 36 ° 1 ′ W ) in the south of the island of South Georgia in the South Atlantic was named by participants in the Second German Antarctic Expedition (1911-1912)

- the Drygalski Island ( 65 ° 45 ' S , 92 ° 30' O ), 1912 discovered during the Australasian Antarctic expedition off the coast Ostantarktikas , named by the head of Douglas Mawson

- Drygalskikammen ( 79 ° 16 ′ N , 12 ° 34 ′ E ), a mountain ridge on the island of Svalbard

- of Mount Drygalski ( 53 ° 2 ' S , 73 ° 23' O ), a hill on the island Heard in the southern Indian Ocean, the surrounding area was explored in 1902 by Drygalski and other participants of the expedition

- the Drygalski crater in the south pole region of the moon

Furthermore, the Bras Enzensperger bay ( 49 ° 27 ′ S , 69 ° 48 ′ E ) on the Kerguelen is named after the meteorologist and mountaineer Josef Enzensperger , who died there during the 1903 expedition .

Awards (selection)

- In 1898 Drygalski received the silver Carl-Ritter-Medal and in 1904 the golden Gustav-Nachtigal-Medal of the Society for Geography in Berlin in recognition of his services as head of the 1st German Antarctic expedition.

- In 1905 he was made an honorary member of the Austrian Geographical Society .

- In 1933 he was awarded the golden Ferdinand von Richthofen Medal by the Society for Geography in Berlin - together with Alfred Philippson and Sven Hedin .

- The Royal Geographical Society awarded him their gold medal ( Patron's Medal ) in 1933 for his glaciological work in the Arctic and Antarctic.

Works (selection)

- Greenland's glaciers and ice sheet . In: Journal of the Society for Geography in Berlin . 27, 1892, pp. 1-62.

- Greenland expedition of the Society for Geography in Berlin 1891–1893 , 2 vols., Kühl, Berlin 1897 ( first volume , second volume )

- On the continent of the icy south , Verlag Georg Reimer, Berlin 1904 (online access in the Internet Archive )

- (Ed.): The German South Pole Expedition 1901–1903 on behalf of the Reich Office of the Interior. , 20 vols. And 2 atlases. Berlin 1905–1931.

- The German South Polar Expedition . 15 volumes and 3 atlases. Berlin 1915.

- The movement of glaciers and ice sheets. : Announcements of the Geographical Society in Vienna , year 1938, pp. 273–283 (online at ANNO ).

- (with Fritz Machatschek): Glacier science . Vienna, Deuticke , 1942.

literature

- Cornelia Lüdecke : German polar research since the turn of the century and the influence of Erich von Drygalski. (= Reports on Polar Research , Volume 158.) (also dissertation, University of Munich 1993) Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research , Kamloth, Bremen 1995. doi : 10.2312 / BzP_0158_1995

- Cornelia Lüdecke: Erich von Drygalski and the establishment of the Institute and Museum for Oceanography . In: Historisch-meereskundliches Jahrbuch , Vol. 4 (1997), pp. 19–36

- Cornelia Lüdecke (Ed.): Hidden Ice Worlds. Erich von Drygalski's report on his Greenland expeditions in 1891, 1892–1893. August Dreesbach Verlag, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-944334-38-7 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Erich von Drygalski in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Erich von Drygalski in the German Digital Library

- Biography from the TU Braunschweig

- Erich von Drygalski - expedition member in the Arctic and Antarctic Biography from the AWI

- Erich von Drygalski in memory of Martin Müller (PDF document; 698 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Edwin Fels: Drygalski, Erich Dagobert von. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3-428-00185-0 , p. 143 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Cornelia Lüdecke: Erich von Drygalski and the establishment of the institute and museum for oceanography . In: Historisch-meereskundliches Jahrbuch , Vol. 4 (1997), pp. 19–36, here p. 20.

- ↑ Member entry by Erich von Drygalski (with a link to an obituary) at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences , accessed on January 28, 2017.

- ↑ Gerd Otto-Rieke: Graves in Bavaria . Alabasta, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-938778-09-1 , p. 28.

- ↑ Berlin City Map Archive , as of December 20, 2008

- ↑ Carl Hanns Pollog: The motorization of Südpolarforschung. Results and Expectations. : Communications from the Imperial and Royal Geographical Society / Communications from the Imperial and Royal Geographical Society in Vienna / Communications from the KK Geographical Society in Vienna / Communications from the Geographical Society in Vienna / Communications from the Geographical Society Vienna in of the German Geographical Society. Organ of the German Geographical Society for the European Southeast , year 1939, p. 26 (online at ANNO ).

- ^ Drygalski-Eiszunge , entry on geographic.org (English, accessed on February 5, 2013).

- ↑ John Stewart: Antarctica - An Encyclopedia . Vol. 1, McFarland & Co., Jefferson and London 2011, ISBN 978-0-7864-3590-6 , p. 458 (English)

- ↑ Hans Meyer: The Kilimanjaro . Dietrich Reimer, Berlin 1900, p. 415 ( archive.org ).

- ↑ Karsten Brunk: Cartographic work and German naming in Neuschwabenland, Antarctica - previous work, reconstruction of the flight paths of the German Antarctic Expedition 1938/39 and revision of the German namesake in Neuschwabenland ( memento from June 26, 2011 in the Internet Archive ). German Geodetic Commission at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences, Series E: History and Development of Geodesy, Publishing House of the Institute for Applied Geodesy, Frankfurt am Main 1986, 24 / Part I, p. 24. (PDF; 391 kB)

- ↑ Drygalski Fjord , entry on geographic.org (English, accessed on February 5, 2013)

- ↑ Geographic Names of Antarctica , United States Board on Geographic Names 1956, p. 111 (accessed October 16, 2011)

- ↑ Drygalskikammen . In: The Place Names of Svalbard (first edition 1942). Norsk Polarinstitutt , Oslo 2001, ISBN 82-90307-82-9 (English, Norwegian).

- ↑ Bras Enzensperger , entry on geographic.org (English, accessed on February 5, 2013)

- ^ Festive meeting to celebrate the seventieth anniversary of the Society for Geography in Berlin . In: Negotiations of the Society for Geography in Berlin . tape 25 , 1898, pp. 244 ( online ).

- ^ The Geographical Society 1936–1942. : Communications from the Imperial and Royal Geographical Society / Communications from the Imperial and Royal Geographical Society in Vienna / Communications from the KK Geographical Society in Vienna / Communications from the Geographical Society in Vienna / Communications from the Geographical Society Vienna in of the German Geographical Society. Organ of the German Geographical Society for the European Southeast , year 1943, p. 184 (online at ANNO ).

- ↑ List of Gold Medal Winners from the Royal Geographic Society , accessed June 17, 2018.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Drygalski, Erich von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Drygalski, Erich Dagobert von |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German geographer, geophysicist, geodesist and polar researcher |

| BIRTH DATE | February 9, 1865 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Koenigsberg |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 10, 1949 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Munich |