Andrée's polar expedition of 1897

Salomon August Andrée's expedition with a gas balloon to the North Pole started on July 11, 1897 and ended in October of the same year with the deaths of three participants: Salomon August Andrée , the engineer Knut Frænkel and the photographer Nils Strindberg . The fate of the men remained a mystery for 33 years until their last camp was discovered in 1930.

The second half of the 19th century is often referred to as the heroic time of the polar journeys. The inhospitable zones around the North and South Poles presented a challenge to courage and technical achievements. Andrée's plans for a balloon trip to the North Pole therefore fit the spirit of his time. He wanted to take off from Svalbard in his balloon and then travel across the Arctic Ocean to the Bering Strait to land in either Alaska , Canada or Russia . He wanted to cross the North Pole or drive past it as close as possible.

planning

In 1893 Andrée bought a hydrogen balloon , christened it Svea and made nine journeys through Sweden starting in Gothenburg or Stockholm , covering a total of 1500 kilometers. The longest journey was from Gothenburg over the Swedish mainland and the Baltic Sea to the island of Gotland . On some of the trips he tested the tow lines he had invented himself and which he wanted to use to steer the balloon in the future. As long as a balloon has the same speed as the wind, it is not possible to steer it with sails. The task of the tow lines was to reduce the speed of the balloon to make it maneuverable. After his test drives, Andrée claimed that the Svea had become a steerable airship with tow lines and sails. A statement that today's balloonists consider impossible. Many of his critics believe that Andrée's belief was a result of his wishful thinking. He also traveled great distances through clouds and had little chance of determining where he was or where he was going. In addition, already in this phase there were problems with the tow ropes, which either tore, knotted themselves or got stuck to objects on the ground. The securing arrangement, which was supposed to eliminate the latter problem, then ensured at the beginning of the actual expedition that many lines simply fell off at the start.

Advertising and fundraising

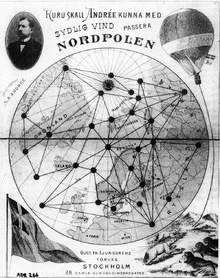

In contrast to Norway , which had made great strides in the competition to reach the North Pole, mainly thanks to Fridtjof Nansen's achievements, Sweden was not able to show any similar successes. The Swedish political and scientific elite were therefore interested in their country catching up with its western neighbor. Andrée was a convincing speaker and had little trouble finding support for his plans. He lectured at the Royal Academy of Sciences and the Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography and received wide approval. During these lectures, Andrée explained in 1895 that a balloon with the following four properties was required for a north polar flight: First, it had to be buoyant enough to carry three people and the scientific equipment, whose weight he calculated at three tons, over the planned route. Second, the envelope of the balloon must be sufficiently strong and tight to withstand a thirty day journey. Third, it should be able to be filled with hydrogen at the launch site and, finally, it should be controllable. Andrée counted modern cameras for aerial photographs , provisions for four months and ballast as the required equipment . He was very optimistic that the four requirements could easily be met. Andrée stated that the balloon, which was larger and stronger than necessary, should be made in France . In addition, some French balloons should have retained their hydrogen filling for more than a year without noticeably losing their buoyancy. Andrée wanted to get mobile hydrogen generators to fill up the balloon at the launch site. With regard to the controls, he referred to his experiments with the Svea and noted that a direction could be obtained that deviated from the wind direction by up to 27 degrees.

Andrée assured his audience that the arctic summer would offer excellent conditions for a balloon ride. Because of the midnight sun, there is no need to land at night, and observations can take place around the clock. A trip without a stop would also shorten the travel time considerably. The tow lines could not get caught on the ground so easily, because there was no vegetation. The low amount of precipitation would minimize the risk of snowfall, which would make the balloon heavier. But even if it will snow, the problem is to be assessed as minor. Andrée explained that the snow thaws at temperatures above zero and is blown away at temperatures below zero because the balloon with tow lines moves slower than the wind. The audience and probably also Andrée were just as ignorant of the frequent storms of the arctic summer as the high humidity of the area with a lot of fog, which increases the risk of ice formation. The academy supported Andrée's project and also his cost calculation, which amounted to 130,800 kroner; this included 36,000 crowns for the purchase of the balloon. Then Andrée received financial support from associations and private individuals, including King Oskar II and Alfred Nobel .

The project also met with great interest in other countries. Both European and American newspapers wrote about the expedition plans, and for the readers the project was painted out in the popular scientific spirit of Jules Verne . Assumptions about the course of the expedition ranged from predicting certain death to assuring that the trip would go off without a hitch, since experts from Paris and Swedish scientists were involved.

In the wake of these discussions, the first well-founded criticism arrived in Sweden. Since Andrée was the first Swedish balloonist, there was no one in the country who had enough knowledge to check Andrée's statements about tow lines and buoyancy. In France and Germany , on the other hand, there had been a balloon tradition for some time, and so the first skeptical comments about Andrée's methods and inventions came from these countries. But even these could not dampen the optimism of the expedition leader. He initiated negotiations with the well-known hydrogen balloon manufacturer Henri Lachambre from Paris and ordered a balloon made of three-layer Chinese silk, which should have a diameter of 20.5 meters. The balloon was originally named Le Pôle Nord (French for North Pole), but shortly before take-off it was renamed Örnen (Swedish for eagle).

One of the scientific goals of the trip was the cartographic evaluation of the overflown area with the help of aerial photographs, and so Andrée, who was also an experienced amateur photographer, developed various new cameras.

First attempt from 1896

Many volunteers had volunteered for the expedition. Andrée's choice fell on the meteorologist Nils Gustaf Ekholm , who had been Andrée's superior on the geophysical expedition as part of the First International Polar Year in 1882 and thus had a good insight into the conditions in the Arctic. The third man selected was the student Nils Strindberg , who dealt with physics and chemistry and was a nephew of August Strindberg . The participants were not selected based on their physical characteristics, nor were they trained to survive in extreme conditions: all three usually worked indoors before the trip, and only Strindberg was relatively young.

On June 7, 1896, the expedition started in Gothenburg with the steamer Virgo , and on June 21 they reached the Danish island ( Norwegian Danskøya ) in the north-west of Svalbard . After two days of exploring the area, they found a suitable place to climb and began building a hangar to house the balloon. The further preparations took several weeks, so that the balloon was only ready to take off on August 1st. However, the wind blew continuously from the north, and after the situation had not changed by August 16, the company was abandoned for the time being. The hydrogen was released again and the journey home started on August 20.

Today it is known that mostly northerly winds prevail on Danskøya, but at that time statements about wind directions and precipitation amounts in the Arctic were purely hypothetical. Even Ekholm, who had been researching the polar climate for some time, was convinced by Andrée. As long as the balloon was still filled, Ekholm took measurements of its ability to hold hydrogen, as he was skeptical in this regard. After these measurements, Ekholm was convinced that the balloon had too many leaks to make a safe journey to the North Pole impossible, let alone continue to Russia or North America. The greatest loss of gas occurred at the seams of the balloon with its innumerable tiny puncture holes, and neither adhesive tape nor special putty could master them. The balloon lost buoyancy, which corresponded to about 68 kilograms, every day. Taking into account the heavy transport load, Ekholm calculated that the balloon would stay in the air for a maximum of 17 days. When the expedition was on its way home for this time, he informed Andrée that he would not take part in the next year's attempt until a stronger and denser balloon was purchased. Andrée ignored his colleague's criticism.

On the return trip Ekholm learned from the chief engineer for hydrogen production that some strange deviations in his series of measurements were due to Andrée's occasional secret refills. The reasons for this self-destructive behavior are still unknown. Some modern commentators on the expedition, such as the author of the semi-documentary book Ingenijör Andrées luftfärd (engineer Andrées Luftfahrt), Per Olof Sundman , suspected that Andrée had become a victim of his successful propaganda and funding campaign. The sponsors and media followed every delay and setback and demanded results. The members of the expedition had been bid farewell by cheering crowds, and now they returned home with no more than a long wait in their luggage. Nansen returned from his Fram expedition around the same time , and the contrast couldn't have been greater. Since the Fram made a stopover on Danskøya on her return voyage without Nansen on board, her captain Otto Sverdrup and Andrée met there. On his own drive home, Andrée met Nansen in Tromsø . In his novel, Sundman put forward the theory that Andrée could not tell the public in this situation that the wind conditions in the Arctic were different than he had hoped and that he had misjudged his balloon and therefore needed a new one.

When it was now clear that the originally planned ascent had not taken place, the enthusiasm in the population was no longer so great, but there were still enough volunteer candidates. Andrée selected the 27-year-old engineer Knut Frænkel as the third expedition member for Nils Ekholm and also hired the aeronaut Vilhelm Swedenborg , a son-in-law of the polar explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld , as a substitute. Frænkel came from Jämtland and was an accomplished sportsman and mountain hiker, who recommended himself strongly for the position of meteorologist, but did not have comparable knowledge as Ekholm. Due to his meteorological diary, it was possible to trace the route of the expedition and its last months very precisely.

The 1897 expedition

Ascent, ride and landing

The following year, the expedition with the two ships HMS Svensksund and SS Virgo set out from Gothenburg on May 18, 1897 for the Danish island. When she got there on May 30, she found the hangar in good condition. The winds seemed to have taken a more favorable direction, and Andrée felt strengthened in the position of expedition leader, especially since the critical Ekholm had been replaced. The balloon was prepared for four weeks and was ready for use from July 1st. On July 11th, there was a steady wind from the southwest, and so after a joint discussion, the start was decided. The top of the hangar was removed and the three explorers climbed into the basket. The expedition's helpers on the ground cut the last ropes and the balloon rose slowly. The lifting of the balloon was documented photographically by the German journalist and polar researcher Theodor Lerner . When the balloon was above water, it was pulled down by the friction of the tow ropes, so that the basket was temporarily submerged in the sea. The friction also twisted the ropes, causing them to fall out of their fittings. This was based on a security order to which Andrée had agreed only reluctantly. In the first minutes of the expedition, almost all tow lines were lost, which corresponded to a weight of 530 kilograms. At the same time, the expedition members threw 210 kilograms of sand to get out of the water. Shortly thereafter, the balloon rose to a height of 700 meters, which was never planned. It was no longer possible to control the vehicle and at the same time the balloon lost more hydrogen than desired at this altitude.

In order to stay in contact with the environment, the expedition had 12 buoys and 36 carrier pigeons on board. The buoys consisted of steel cylinders encased in cork and were intended to return to civilization with the help of the ocean currents after being dropped over water or sea ice. Two of these buoys were found years later with news (one on May 14, 1899 in Iceland , the other on August 27, 1900 in the Norwegian province of Finnmark ) and came from a time only a few hours after departure. The carrier pigeons came from northern Norway , where they had been bought for the expedition by the newspaper Aftonbladet . It was hoped that they would find their way back to their homeland, so they gave them a form in Norwegian requesting that the letter be forwarded to Stockholm. Andrée released several of these pigeons, none of which reached the mainland. However, one landed after a two-day flight on the Norwegian seal-catching ship Alken and was shot. The message was dated July 13th and, in addition to information about position and direction of travel, had the text “Have a good trip. Everything is fine on board ” . None of the messages found reported about the accident at take-off or mentioned a worried situation on board. However, from Andrée's diary it is clear how unbalanced the air journey was.

In the course of the voyage, the Örnen had become damp and heavy from drizzle and fog, and all the sand and some of the equipment were thrown overboard to keep it in the air. The wind turned several times during the journey and occasionally even died down completely. The balloon traveled for 10 hours and 20 minutes without contact with the ground. This was followed by a 55-hour, bumpy journey in different directions and with a lot of ground contact, until the increasingly icy balloon came to a complete stop and it was decided to abort the journey. The balloon took off on July 11 at 1:50 p.m. GMT and landed on July 14 at 7:30 a.m. GMT, which is 65:40 hours during which, according to Andrée's diary entries, the travelers barely got to sleep. Since the landing was carried out in a controlled manner, everyone on board was unharmed, including the pigeons in their wicker baskets. The equipment, including Strindberg's delicate optical instruments, was also not damaged. In total, the polar explorers had come to latitude 82 ° 56 ′ north, which was about a third of the distance to the North Pole.

Walking on the ice

Before the three men began their walk, they spent a week in a tent by the unusable balloon, preparing and discussing where the journey should go. The North Pole, which is about 800 kilometers away, was never considered as a possible target. The fact that the large pole buoy, which was originally supposed to be dropped over the North Pole, had already gone overboard as ballast during the voyage (it was found on September 11, 1899 on the north coast of the island of Kongsøya, which belongs to King Karl Land, in the east discovered by Spitzbergen), suggests that the actual project had already been abandoned. Two storage depots with food and ammunition that had been set up as security for the expedition were up for discussion. The first was at Cape Flora on Franz-Joseph-Land and the second on a small group of islands belonging to Svalbard ( Seven Islands , see map). Since the maps of the area were still very poor at that time, the travelers believed that they were about the same distance from the depots. So they decided on Cape Flora , where more supplies were stored. They had to travel about 350 kilometers to get there, Seven Islands was about 320 kilometers away.

Before setting off, the expedition participants debated what and how much they should take with them. A lot of emergency equipment had been stowed in a shed above the balloon basket. These included rifles, a tent, snowshoes , sledges and an assemblable boat frame that could be covered with the silk of the balloon. These items had not been carefully selected, nor had there been sufficient study of what the local population used in these extreme conditions. In this, Andrée differed not only from later explorers, but also from many earlier explorers. In his book “ Vår position är ej synnerligen god… ” (Our position is not particularly good…) Sven Lundström points out that the sledges designed by Andrée were extremely impractical for the difficult terrain with its gullies and countless ice floes that became barricades piled up or lined with frozen pools of water and muddy ice. As the Eskimos were not guided by the light sledges , the journey was considerably more difficult than necessary. The clothes were also unsuitable. It wasn't made of furs, but of woolen coats, cardigans, flannel shirts and trousers with rain protection. Despite this protection, the clothes were always wet or clammy due to the many pools of water and the typically foggy and humid arctic summer air. Drying things was also problematic, and the best method was to keep wearing them and using your own body heat to dry them.

Strindberg took more photos in the first week than on the rest of the trip. Among other things, he took twelve pictures that could be put together to form a closed panorama around the landing site. But even later, Strindberg recorded the daily life of the small company with the constant latent dangers and laborious progress. In the following three months on the ice, he took around 200 photos with his seven kilogram camera. Andrée and Frænkel carefully documented the experiences of the expedition and the geographical positions, Andrée very detailed and clear in his diary and Frænkel in his meteorological report. Strindberg kept a more personal diary in shorthand style, where he recorded his reflections on the trip and numerous communications to his fiancée Anna Charlier .

There was a large supply of food on board the Örnen , but it was more suitable for a balloon ride than a walk. Andrée had considered replacing part of the sand ballast with food that could also be thrown overboard if the balloon should become lighter. Otherwise food would be needed during wintering. There was a total of 767 kilograms of food on board, 200 kilograms of drinking water, a few boxes of sparkling wine, port wine, beer and similar drinks that had been given by sponsors and the manufacturers. There was also lemon juice to protect against scurvy , albeit in a smaller amount than other polar explorers considered necessary. Much of the food was canned, such as pemmican and other meat products or cheese and condensed milk .

Some of the food had already been discarded. The men took large quantities of what was left when they left the landing site on July 22nd. Each sled was loaded with about 200 kilograms. This weight was too great as the sleds threatened to break and the men who pulled them became too exhausted. After a week, the expedition members left behind a pile of food, kitchen equipment and other items that were not considered necessary, so that the sledges weighed only 130 kilograms. However, it now became necessary for travelers to hunt for food. In the further course of the march they mainly shot polar bears , but also walruses and other seals .

You quickly noticed that the fight against the two meter high ice walls did not bring the group towards the goal, because the ice was drifting in the opposite direction. So on August 4th, after a long discussion, they decided to change direction to the Seven Islands to the southwest . With the current, they hoped to be there after about 6 to 7 weeks of hiking. The ground was particularly heavy in this direction at times, and they sometimes had to crawl on all fours or take longer detours. On the other hand, there were also easier passages with larger shallow floes or areas of open water where the group could use their boat as a safe means of transportation. “Paradise” , wrote Andrée on August 6th. “Big, smooth ice floes with fresh water puddles full of juicy water and now and then a young polar bear with tender meat .” Now they made significant progress, but soon afterwards the wind and ice drift turned and they drifted back again. In the weeks that followed, the wind was heading southwest or northwest, which they tried to compensate by moving directly westwards. Andrée noted the extremely arduous conditions in his diary more and more often, and slowly it became apparent that Seven Island could not be reached.

When the temperatures began to drop and the first snowstorms occurred, the participants realized on September 12th that wintering on the ice would be necessary. They set up camp on a large ice floe and let themselves drift with the current without affecting the course. They drifted south towards the White Island (Kvitøya) , which they sighted for the first time on September 15, and built a winter house designed by Strindberg out of snow, the walls of which were hardened with icy water, to protect against the cold. When Andrée saw how quickly they were drifting south, he wrote down his hope that they would get far enough to be able to feed themselves solely on the sea. On October 2nd, the ice floe that was being pressed against the White Island began to break right under the almost completed hut. The expedition members moved to the island with their belongings, which took three days. Shortly afterwards, Andrée wrote a remark in his main diary that can be considered the last part of the related notes in this booklet. “Nobody has lost heart. You can hold out with such comrades, whatever may come. "

After moving to the island, the expedition members made only a few recordings in the days that followed. A notebook with his latest reports was found in the left breast pocket of his coat on Andrée's body, although the five pages were badly damaged and largely illegible. At least there were indications that the construction of a new dwelling, which was apparently planned for October 6 or 7, could no longer be carried out due to the bad weather conditions. Frænkel's entries in the weather diary and Strindberg's notes also ended shortly before or soon after. It can therefore be assumed that the three died a few days after their arrival on the island. None of the men described the approaching end in more detail.

Possible causes of death

The exact cause of death could best have been clarified if the bodies had not only been examined superficially, but the bodies were, 33 years later, taken directly to Stockholm and cremated without an autopsy . The question of the cause of death aroused great interest among historians and medical professionals. The participants' diaries were read carefully to find clues in the description of the food or in the symptoms the travelers experienced. The descriptions of the place of death and the location were also examined. From this it was realized that Andrée, Frænkel and Strindberg usually only ate small portions of the canned food and dried goods that they had carried in the balloon. They lived mainly on semi-raw polar bear or seal meat. They often had sore feet, sores, and diarrhea, and were mostly tired, drenched, and cold. At their last camp on the White Island, they left some of their equipment on one of the sleds in front of the tent, suggesting that they were too exhausted, too sick, or too resigned to put these items in better protection. Strindberg probably died first because he was found buried in a crevice and covered with stones. Frænkel was lying on the ground and had apparently died in the tent. Andrée's remains were discovered on a small ledge just above the tent.

The best known and most widespread hypothesis is that of the doctor Ernst Tryde, which he put forward in his book De döda från Vitön (The Dead of the White Island) in 1952 , after the remains of meat from the expedition had been examined. He assumed that the men probably nematodes were attacked after having Trichinella had eaten infected polar bear meat. Larvae of the species Trichinella spiralis have been found in polar bear carcasses at the camp site , and several commentators believe this explanation. Critics of this thesis, in turn, attest that the symptom of diarrhea, the presence of which Tryde's theory relies on, may simply be a reaction to poor food and a battered physical condition, while other specific symptoms of roundworm infestation are absent. In addition, Fridtjof Nansen and his companion Hjalmar Johansen had been eating polar bear meat in the same area for 15 months without encountering any similar problems.

Another explanation was the poisoning with vitamin A from polar bear liver, but Andrée's diaries show that the expedition was aware of this danger and therefore abandoned the liver. The theory about carbon monoxide poisoning has few supporters because the group's primary stove was found switched off. Other explanations range from lead poisoning from canned food to scurvy, botulism , suicide with the help of the morphine carried along , freezing to death, attack by polar bears, to dehydration in combination with general fatigue and apathy . Rolf Kjellström believes in his book Andrée-expeditions och dess undergång: tolkning nu och då (The Andrée expedition and its downfall: interpretations today and in the past) more in the latter variant and points out the state in which the group must have been, when she was forced to vacate her winter quarters on the ice floe in order to move to the glaciated island. Kjellström stated that it is less surprising that they died, but rather that they lasted so long.

The Swedish doctor and author Bea Uusma , who spent more than a decade studying the details of the expedition and was also able to examine original pieces, considered trichinae as the cause of death in her book Expeditions: min kärlekshistoria (The Expedition: A Love Story) , published in 2013 unlikely, especially since the mortality rate in such cases is generally quite low. In their opinion, damage to Strindberg's clothing rather indicated that at least he might have died when a polar bear attacked. In the case of Andrée and Frænkel, she could not make a more precise delimitation at this time.

Public Speculation and Discovery

In the 33 years after the expedition disappeared, it was part of the cultural myth in Sweden and other countries. For several years there was an active search for her, among other things during the travels of the Swedish polar explorer Alfred Gabriel Nathorst . But even after these activities gradually stalled, there were constant rumors and suspicions with regular reports in international newspapers about possible traces of the missing persons. A larger collection of US newspaper clippings from 1896 to 1899, which was published under the title Mystery of Andree ("The Andrée Mysterium"), shows that the media interest was even greater after the disappearance of the expedition than before the departure. The assumptions about the fate of Andrée and his companions were manifold and were based on reports of discoveries of a structure that resembled a balloon basket, or allegedly emerged balloon silk. There were stories of people falling from the sky and fortune tellers claiming to have seen the stranded balloon far from where it had actually been. Lundström writes that some of the reports resembled modern sagas and reflected the lack of respect for the indigenous people of the Arctic. These were often portrayed as savages who should have murdered the three men or at least left them to their fate. In 1930 all speculation came to an end when the crew of the Norwegian sealer MS Bratvaag discovered the last camp of the missing.

The Bratvaag came from Ålesund and was hunting near Kvitøya on August 5, 1930 . The ship also had a scientific expedition on board, led by Gunnar Horn, to explore the glaciers and lakes of the Svalbard archipelago . The seal and whaling ships of this time did not normally reach the White Island, as it was mostly surrounded by a wide band of sea ice and was often hidden in fog. However, the summer of 1930 was unusually warm and the surrounding sea was virtually ice-free. Kvitøya was known as a good hunting ground for walruses, and as the fog was surprisingly thin, part of the crew of the Bratvaag took the opportunity to go ashore on the so-called “inaccessible island”. Two of the sealers, Olav Salen and Karl Tusvik, who were looking for drinking water, came across Andrée's boat. This was frozen on one of the sleds under a snow mountain and full of equipment, including a boat hook with the inscription "Andrées polar expedition, 1896". When the ship's captain, Peder Eliassen, was shown this hook, he ordered the crew and scientists on board to search the place. In addition to countless items of equipment and clothing, some of the diaries and two skeletons were found, which were identified as those of Andrée and Strindberg by means of monograms on the clothing. The ship left the island to continue hunting and exploring the ice. They wanted to come back later because they hoped the ice would continue to melt and more finds would come to light. In addition, reports of the discoveries on Kvitøya were reported to the press and the Norwegian authorities. However, when they returned to the island on August 26, the sea was too rough to go ashore.

Further finds were made by the Norwegian seal-catching ship MS Isbjørn , which came from Tromsø and had been hired by journalists who wanted to haul in the Bratvaag . After they did not succeed in having the first interview with the crew of the Bratvaag , they decided to try to go ashore on Kvitøya. They reached the island on September 5th and found that the ice had continued to decline and further discoveries were possible. Among the discoveries was Frænkel's almost completely preserved upper body and remains of the abdomen, as well as other documents and a lead box with Strindberg's films and cards.

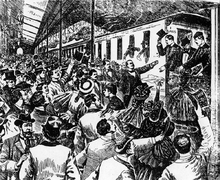

The Bratvaag entered the port of Tromsø on September 2nd, the Isbjørn on September 16th. There the finds were handed over to a scientific commission that was subordinate to the governments of Sweden and Norway. The three bodies were brought aboard the Svensksund on September 19 and transferred to Stockholm, where they arrived on October 5. On the same day, with great sympathy, the coffins were taken through the city to Stockholm Cathedral Storkyrkan , where the funeral service took place. On October 9, Andrée, Frænkel and Strindberg were cremated and buried in a common grave on Norra begravningsplatsen .

The expedition in the eyes of posterity

At the time the expedition was on its way, the daring Andrées project fueled the national pride of Sweden. It was dreamed that the country could take a leading position in the exploration of the Arctic. Andrée was generally referred to as "Engineer Andrée", which reflected the high status of engineers, who were portrayed as representatives for social improvement through scientific success. The explorers were honored by the nation when they left and mourned again when they disappeared. After their bodies were found, they were honored as selfless victims of scientific progress and for their heroism in the three-month struggle for survival. The historian Sverker Sörlin believed that the homecoming of the body must have been one of the most solemn and grandest expressions for national mourning in Sweden. According to Sörlin, this can only be compared with the mourning for the victims of the Estonia disaster of 1994.

In recent times, Andrée's heroic motives have been questioned more and more. Per Olof Sundman made a first summary in 1967 in his semi-documentary novel Ingenjör Andrées luftfärd , where he portrayed Andrée as a victim of the high demands of the media and the scientific and political establishment of Sweden, who was driven more by his fear than his courage. Sundman's portrayal of the characters in this drama as blind spots in Swedish national culture and the role of the press were later followed by Jan Troell in his 1982 film The Eagle's Flight , which received an Oscar nomination for best foreign language film , and its documentary Ballonfahrt in den Tod (1997) continued. Sundman and Troell referred in their works to an entry in the diary of Andrée, which they considered to be an important key point in assessing his own motivation and convictions. Both of them questioned whether his own personal assessment, which was written in the we-form, was shared equally by his two companions. Andrée wrote on the evening of July 12, 1897, on the second day of the balloon flight: “It is really strange to float here over the polar sea. We are now the first to fly around here in a balloon. When will someone do the same? Will people think we're crazy or follow our example? I cannot deny that all three of us have a sense of pride. We find that we can safely die after doing this. "

With regard to Nils Strindberg's role in the expedition, the opinion of many commentators has improved. Above all, the bravery with which the physically untrained student continued to photograph under conditions that were permanently close to collapse due to the exhaustion from the cold, is shown appreciatively. The artistic quality of the photos was also noted. Of the approximately 200 negatives that were found in water-filled containers on Kvitøya, John Hertzberg from the Royal Technical University in Stockholm was able to restore 93 with great scientific effort. In his 2004 article, Recovering the visual history of the Andrée expedition: A case study in photographic research , Tyrone Martinsson complained that previous researchers placed too much traditional focus on written sources such as diaries, whereas photographs are particularly important.

Modern authors judge Andrée, who sacrificed not only his own life but also the life of his fellow campaigners, with varying degrees of severity, depending on the extent to which they see him more as an accomplice or a victim of the national hysteria of the time.

Exhibitions

Some of Andrée's expedition equipment is exhibited today in the Nanoq Museum in Jakobstad , Finland. There are also items from other famous polar journeys, for example by Fridtjof Nansen and Roald Amundsen . Other items are in the Andrée Museum in Gränna , Sweden.

Artistic reception

- The Swedish-Dutch composer Klas Torstensson (born 1951) dealt with the subject several times.

- Barstend Ijs (1986), multimedia piece using ice sounds. In an interview he described: "When you hear this cracking in the ice that comes from very far away and wanders across the ice surface - that's just a fantastic sound that creates a mixture of emotions and pure audio interest."

- The Last Diary (1994) for voice and ensemble

- The Expedition (1998), opera, premiered on June 11, 1999 at the Holland Festival in Amsterdam.

- The German writer Kurd Laßwitz took the expedition as a template for the beginning of the plot of his science fiction novel Auf Zweiplanet (1897). Here, however, the influence of Martians leads to the failure of the balloon flight expedition directly at the pole.

Receipts used

- Article Andrées polar expedition in the version of June 6, 2006 on the Swedish language Wikipedia (mostly translation of the corresponding English article) with the following evidence:

- Andrée, SA, Nils Strindberg, Knut Frænkel (1930). Med Örnen mot polen: Andrées polar expedition in 1897. Stockholm: Bonnier.

- “Andrées färder” ( Memento of February 11, 2006 in the Internet Archive ), Swedish Balloon Association.

- Kjellström, Rolf (1999). "Andrée expeditions och dess undergång: tolkning nu och då", i The Centennial of SA Andrée's North Pole Expedition: Proceedings of a Conference on SA Andrée and the Agenda for Social Science research of the Polar Regions , red. Urban Wråkberg. Stockholm: Centrum för vetenskapshistoria, Swedish Academy of Sciences . ISBN 91-7190-031-4

- Lautz, Thomas: With the balloon to the North Pole. 100 years ago: Start of the fateful Andrée expedition. In: Münzen & Papiergeld Nov. 1997, pp. 7–13 (history and complete listing of the medals minted in honor of Andrée).

- Lundström, Sven (1997). “Vår position är ej synnerligen god…” André expeditions i svart och vitt. Borås: Carlssons förlag. ISBN 91-7203-264-2

- Martinsson, Tyrone (2004). "Recovering the visual history of the Andrée expedition: A case study in photographic research" ( Memento of April 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). Research Issues in Art Design and Media , ISSN 1474-2365 , issue 6.

- “The Mystery of Andree” , Large Archive of American Newspapers 1896–99.

- Personne, Mark (2000). Andrée expeditionens men dog troligen av botulism (PDF; 88 kB) . Doctors newspaper, Vol. 97, Issue 12, pp. 1427-1432.

- Sörlin, Sverker (1999). The burial of an era: the home-coming of Andrée as a national event. In: Urban Wråkberg (Red.): The Centennial of SA Andrée's North Pole Expedition: Proceedings of a Conference on SA Andrée and the Agenda for Social Science Research of the Polar Regions. Stockholm: Centrum för vetenskapshistoria, Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien, ISBN 91-7190-031-4 .

- Sundman, Per Olof (1967). Ingenjör Andrées Luftfärd. Stockholm: Norstedt. Engineer Andrées Luftfahrt (from the Swedish by Udo Birckholz). People and World, Berlin 1971.

- Tryde, Ernst Adam (1952). De döda på Vitön: singing om Andrée . Stockholm: Bonnier.

- Sörlin, Sverker. Article Andrée expeditions. In: Swedish National Encyclopedia . *

literature

- Detlef Brennecke (Ed.): With the balloon towards the pole: 1897 , Ed. Erdmann, Stuttgart, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-522-60043-6 .

- Heinz Straub: Lost in the Arctic. The fateful balloon flight of the Andrée expedition , Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-7973-0461-7 .

- Theodor Lerner: polar driver. Under the spell of the Arctic, experiences of a German polar explorer , Oesch, Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-0350-2014-0 .

- SA Andrée: Towards the Pole (original reprint of the volume published in Leipzig in 1930), König, Greiz 2008, ISBN 978-3-934673-73-1 .

- Bea Uusma: The expedition. A love story: How I solved the puzzle of a polar tragedy . btb Verlag, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-442-75497-7 .

- Swedish original version: Expeditions: min kärlekshistoria. Norstedts, Stockholm 2013, ISBN 978-91-1-305115-4 .

Remarks

- ↑ See the article Klas Torstensson in the English Wikipedia

- ↑ See the article Expeditions on Swedish Wikipedia

Web links

- Andrée Museum in Gränna on the expedition (Swedish)

- Detailed report on the expedition with further links

- Kvitøya - White Island Map (English)