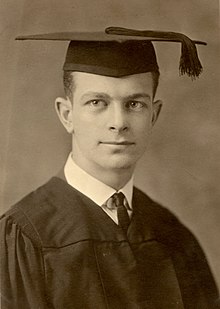

Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (born February 28, 1901 in Portland , Oregon , † August 19, 1994 in Big Sur , California ) was an American chemist . He received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1954 for his research on the nature of chemical bonds and their application in elucidating the structure of complex substances. In 1963 he received the Nobel Peace Prize for his great commitment retrospectively for 1962 as a special award for his work against nuclear weapon tests . Along with the physicist and chemist Marie Curie, Pauling is the only winner of two different Nobel Prizes to date.

Life

The first years

Pauling was born in Portland , Oregon in 1901 . His father, Hermann Heinrich Wilhelm Pauling, a pharmacist whose parents immigrated from Freiburg im Breisgau , moved with his family from one city to the other between 1903 and 1909 and returned with her to Portland last year. Even as a child, Pauling was an insatiable reader . At one point his father even wrote a letter to a local newspaper asking for suggestions for other books to study. In 1910 his father died of a ruptured stomach ulcer and left a woman with livelihood problems and now three half-orphans .

While in high school , his school friend, Lloyd Jeffress, had a small chemistry lab in his bedroom. The experiments with Jeffress inspired Pauling to later become a chemist . Even during the high school Pauling went on chemical experiments and borrowed most of the equipment and materials from an abandoned steel factory near his grandfather worked as a night watchman at.

Pauling was a member of the Lutheran Church at a young age , but joined the Church of the Unitarian-Universalist Church at a mature age . As a member, he publicly confessed to being an atheist two years before his death.

College years

At the age of 16, Pauling enrolled at the Oregon Agricultural College (OAC), now Oregon State University , in 1917 . He took mathematics, physics, and chemistry and worked to finance his studies while attending a variety of lectures at the same time.

In his final two years in college, Pauling learned the work of Gilbert N. Lewis and Irving Langmuir , who studied the electronic structure of atoms and the chemical bonds that enable them to form molecules . He decided to focus his research on how the physical and chemical properties of substances are related to their atomic structure. So he became a co-founder of a new science, quantum chemistry .

In his senior year of college, he met a fellow student Ava Helen Miller, and married her on June 17, 1923. The couple had three sons and a daughter.

In 1922 Pauling graduated from the OAC with a bachelor's degree in chemical engineering and began postgraduate studies in chemistry at Caltech in Pasadena, California . He used in his final research X-ray diffraction to crystal structures to determine. During his time at Caltech, he published seven papers on the crystal structures of minerals and received his doctorate in chemistry summa cum laude in 1925 .

Early scientific career

With the help of a Guggenheim grant , Pauling traveled to Europe in 1926 to study with Arnold Sommerfeld in Munich , Niels Bohr in Copenhagen and Erwin Schrödinger in Zurich . All three worked in the new field of quantum mechanics . Pauling had already dealt with quantum mechanics during his time at the OAC and now wanted to see whether they could help him understand his subject - the electronic structure of atoms and molecules.

He devoted the two years in Europe entirely to his work and decided that this should be the future focus of his research. This made him one of the first scientists in the field of quantum chemistry. In 1927 he took over an assistant professorship at Caltech for theoretical chemistry .

Pauling's career at Caltech began with five very productive years, during which he continued his X-ray studies on crystals and occupied himself with quantum mechanical calculations on atoms and molecules. During this time he published an estimated 50 articles. In 1929 he was appointed associate professor and in 1930 he was given a full professorship . In 1931 he received the Langmuir Prize from the American Society for Chemistry for the most significant work in the field of pure science by a person under the age of 30.

In the summer of 1930, Pauling traveled back to Europe to learn more about the use of electrons in diffraction studies, which were similar to his X-ray diffraction studies. Together with one of his students, LO Brockway , he built an electron diffraction instrument at Caltech and used it to study the molecular structure of a large number of chemical substances.

In 1932 he introduced the concept of electronegativity . Using the numerous properties of molecules, such as the energy it takes to break chemical bonds or the dipole moments of molecules, he determined numerical values for most elements. He arranged these values on a scale, the Pauling scale for electronegativity, with which the nature of bonds between atoms and molecules can be determined. (Another unit of measure for electronegativity was defined by Robert S. Mulliken and is broadly the same as Paulings. However, the Pauling scale is more widely cited scientifically.)

Working on chemical bonds

In the 1930s, Pauling began with the publication of essays on the nature of chemical bonds in 1939 in his famous book The Nature of the Chemical Bond (Original title: The Nature of the Chemical Bond ) have been published. He received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1954 for his work in this area in particular, “for his research into the nature of chemical bonds and their application to elucidate the structures of complex substances”.

Building on his work, Pauling published the concept of hybridization . Usually, the electrons of an atom are described as being on different atomic orbitals (referred to as s , p , etc.). It turned out, however, that to describe bonds in molecules, it is better to construct functions in which both parts take on properties from one another. The 2s and the three 2p orbitals of a carbon atom can be combined to form four energetically equivalent orbitals (called sp 3 hybrid orbitals ). This allows the molecular bonds in carbon compounds such as methane to be represented in a suitable manner. Likewise, the 2s orbital can be combined with two 2p orbitals to obtain three equivalent orbitals (called sp 2 hybrid orbitals ) which, together with the remaining unhybridized 2p orbital, are suitable for describing the molecular bonds of some unsaturated carbon compounds such as ethene . The molecular bonds of other types of molecules can also be explained by other hybridization schemes.

Another area of his research was the relationship between an ionic bond , in which electrons are transferred between atoms, and a covalent bond , in which the electrons are evenly distributed between atoms. Pauling showed that both types of attachment are merely extremes between which most common attachments lie. Pauling's concept of electronegativity was particularly useful here, because the difference in electronegativity between two atoms is the most reliable indicator of the degree of ionization of the bond.

The third of his research topics, which Pauling investigated under the umbrella of the nature of chemical bonds , was the enumeration of the structures of aromatics , especially the prototype benzene . The most accurate description of benzene up to now as far as we know today was by the German chemist Friedrich Kekulé . He viewed the connection as a constant change between two structures, both with alternating single and double bonds , each with the double bond at the point where the single bond of the other structure is located. With a suitable description based on quantum mechanics, Pauling showed that there is an intermediate structure that contains aspects of both. The structure represented a superposition of both structures rather than a quick change between them. The term resonance or mesomerism was given to this phenomenon later. In a certain way, the phenomenon resembles that of hybridization described earlier in that it also involves more than one electronic structure to achieve an intermediate result.

Working on biological molecules

In the mid-1930s, Pauling decided to open up new areas of interest. In his early years he mentioned his lack of interest in the study of molecules with biological significance. But as Caltech began to focus more and more on biology, Pauling began to work with great biologists such as Thomas Hunt Morgan , Theodosius Dobzhansky , Calvin Bridges and Alfred H. Sturtevant , as he developed an interest in biological molecules.

His first work in this area was on the structure of hemoglobin . He was able to demonstrate that the hemoglobin molecule changes its structure when it binds or releases an oxygen atom . As a result of these investigations, he decided to make a thorough study of the structures of proteins in general. To do this, he returned to his old method of X-ray diffraction. Protein molecules are much less suitable for this technique than crystalline minerals. The best X-ray photographs of proteins were made by the British crystallographer William Astbury in the 1930s . But when Pauling tried in 1937 to take part in Astbury's investigations, he did not succeed.

It took Pauling eleven years to explain the problem: while his mathematical analysis was correct, Astbury's images were captured in such a way that they were tilted to their expected positions. Pauling formulated a model of the structure of hemoglobin, in which the atoms are arranged in a helix , and transferred this idea to proteins in general. He published the fundamental studies on the secondary structure of proteins ( alpha helix , beta leaflet ) with his colleague Robert B. Corey (whom he had brought to Caltech as an assistant in 1937 and who carried out the X-ray structure analyzes) and with the visiting scientist at Caltech Herman Branson around 1951. The double helix that James Watson and Francis Crick postulated for deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) can also be traced back to this helix structure . Pauling also came very close to this structure. Although his assumed structure of DNA was not entirely correct, many familiar with his work believe that Pauling would soon have come to the same conclusion as Watson and Crick if Rosalind Franklin , whose work was the basis of Watson and Crick's publication, gave him would not have come before.

Pauling also dealt with enzyme reactions and showed in 1949 with Seymour Jonathan Singer and Harvey Itano that sickle cell anemia can be traced back to a change in one molecule (hemoglobin), as was later shown in only one amino acid . As a result of this work he dealt with the structure of antibodies and was involved in the development of the first synthetic antibodies in 1942.

Engagement against nuclear weapons and nuclear weapon tests

The Second World War made a fundamental change in Pauling's life. Up until this point he was fairly apolitical, but as a result of his experience he became involved as a peace activist. Pauling was also an atheist . In 1946 he became a member of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists (Chairman was Albert Einstein ; the other seven members were Harold C. Urey (Vice-Chairman), Hans Bethe , TR Hogness , Philip M. Morse , Leó Szilárd , Victor Weisskopf and Pauling) . The committee wanted to educate the public about the dangers posed by nuclear weapons. In 1948 he received the Medal for Merit , at that time the highest civilian award in the USA. Just a few years later, however, the US State Department refused him a passport because of his political commitment when he was invited to speak at a scientific conference in London in May 1952. The aim of this conference was to deal with the helix structure of proteins. Had he been able to attend this conference, he might have discovered the true structure of DNA sooner. The denial of the pass led to protests from European and American scientists such as Robert Robinson and Albert Einstein . He received another passport for a conference in France in July 1952.

In 1957 Pauling began a petition campaign together with the biologist Barry Commoner (1917–2012). He had investigated the distribution of radioactive 90 Sr in the milk teeth of children across North America and had come to the conclusion that the above-ground nuclear tests pose major health risks from the radioactive fallout . In 1958, Pauling and his wife submitted a United Nations petition to the US government, signed by more than 11,000 scientists, calling for an end to nuclear testing. The public pressure that followed led to a moratorium and test ban, which John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev signed in 1963. On the day the treaty came into force, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Pauling the Nobel Peace Prize :

"Linus Carl Pauling, who ever since 1946 has campaigned ceaselessly, not only against nuclear weapons tests, not only against the spread of these armaments, not only against their very use, but against all warfare as a means of solving international conflicts."

"Linus Carl Pauling has always campaigned relentlessly since 1946, not only against nuclear weapons tests, not only against the spread of nuclear weapons, also not only against their use, but against all warfare as a measure to resolve international conflicts."

Many of Pauling's critics, including many scientists who acknowledge his contribution to chemistry, saw him as a naive advocate of Soviet communism . He was quoted by an internal Senate security committee which called him "the most important scientist in practically every activity of the communist peace offensive in this country". An extraordinary headline in Life Magazine characterized his 1962 Nobel Peace Prize as "Strange Denigration from Norway".

Establishment of orthomolecular medicine

In 1966, at the age of 65, he began to adopt the ideas of the biochemist Irwin Stone (1907–1984), who saw large doses of vitamin C as a remedy for colds . Pauling, however, went even further and believed that vitamin C could also prevent cancer and prevent the spread of the HIV virus . He himself consumed about 18 grams of vitamin C every day and counteracted almost every medical problem with bold formulations ("Vitamins! Vitamins!").

Pauling's beliefs have repeatedly caused controversy and have repeatedly been classified as pseudoscience . While most scientists do not believe Pauling's assumptions are correct, a few believe that this is one of the cases in which natural substances in the body could prevent disease. Orthomolecular medicine developed based on Pauling's theses .

1973 founded Pauling in Menlo Park , California, together with the biochemist Arthur B. Robinson and the chemist Keene Dimic the Institute of Orthomolecular Medicine (German: Institute of orthomolecular medicine ), which later in The Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine was renamed.

One of his students and former employees at the institute, Matthias Rath , attacked the thesis of the healing power of high-dose vitamins and extended it comprehensively controversial alternative medicine " Zellularmedizin ".

Pauling died of prostate cancer at the age of 93 on his farm in Big Sur , California .

Awards, honors, memberships

In addition to receiving the Nobel Prizes for Chemistry and Peace:

- 1931 Irving Langmuir Award , American Chemical Society (ACS)

- 1933 member of the National Academy of Sciences

- 1941 William H. Nichols Medal , ACS (New York Section)

- 1946 Willard Gibbs Medal

- 1947 Davy Medal

- 1947 TW Richards Medal

- 1948 Medal for Merit from the US President

- 1951 Gilbert Newton Lewis Medal

- 1952 Pasteur Medal , French Biochemical Society

- 1955 Addis Medal, National Nephrosis Foundation

- 1955 John Phillips Medal, American College of Physicians

- 1956 Amedeo Avogadro Medal

- 1957 Paul Sabatier Medal

- 1957 International Hugo Grotius Medal

- 1960 namesake for the Pauling Islands off the west coast of Graham Land, Antarctica

- 1965 Medal of the Romanian Academy of Sciences

- 1966 Linus Pauling Award , the ACS Prize is named after him and he is the first to be awarded

- 1966 silver medal Institut de France

- 1967 Roebling Medal

- 1968 International Lenin Peace Prize

- 1974 National Medal of Science

- 1977 Lomonosov gold medal

- 1979 NAS Award in Chemical Sciences (National Academy of Sciences)

- 1981 John K. Lattimer Medal, American Academy of Urology

- 1984 Priestley Medal , American Chemical Society

- 1984 Arthur M. Sackler Foundation chemistry prize

- 1986 Lavoisier Medal

- 1989 Vannevar Bush Award , National Science Board

- 1990 Richard C. Tolman Medal, American Chemical Society Southern California Section

- 1991 The asteroid (4674) Pauling was named after him on the occasion of his 90th birthday

- 1994 Benjamin Franklin Medal for Distinguished Public Service of the American Philosophical Society

Pauling received 47 honorary doctorates (including Oxford, Cambridge, Sorbonne, Princeton, Chicago), the first in 1933.

In 2008 it came on a 41-cent US postage stamp.

He was a member of numerous academies ( Norwegian Academy of Sciences , Soviet Academy of Sciences , Leopoldina , Royal Society (1948), Royal Society of Edinburgh , Royal Institution , Académie des sciences (1948)). He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences (1933), the American Philosophical Society , the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1944), and the American Association for the Advancement of Science .

In 1965 Pauling became honorary president of the International Society for Research on Nutrition and Vital Substances , of which he had been a member since 1958. He was also president of the “scientific advisory board” in the World Association for the Protection of Life .

Fonts (selection)

Articles in specialist publications

- with Alfred E. Mirsky: On The Structure of Native, Denatured, and Coagulated Proteins. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . (PNAS). Washington DC 22 (1936), No. 7 (July), ISSN 0027-8424 , pp. 439-447.

- with Carl Niemann: The Structure of Proteins. In: Journal of the American Chemical Society . Washington DC 61 (1939), ISSN 0002-7863 , pp. 1860-1867.

- with Dan H. Campbell and David Pressman: The Nature of the Forces Between Antigen and Antibody and of the Precipitation Reaction. In: Physiological Reviews . Bethesda Md 23 (1943), No. 3 (July), ISSN 0031-9333 , pp. 203-219.

- with Harvey A. Itano, SJ Singer and Ibert C. Wells: Sickle Cell Anemia, A Molecular Disease. In: Science . Washington DC 110 (1949), No. 2865 (November 25), ISSN 0036-8075 , pp. 543-548.

- with Robert B. Corey: The Polypeptide-Chain Configuration in Hemoglobin and Other Globular Proteins. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. (PNAS). Washington DC, 37 (1951) 5 (May), ISSN 0027-8424 , pp. 282-285.

- with Robert B. Corey: A Proposed Structure for the Nucleic Acids. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. (PNAS). Washington DC 39.1953, ISSN 0027-8424 , pp. 84-97.

- How my interest in proteins developed. In: Protein Science. (PS). Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor 2.1993, 6, ISSN 0961-8368 , pp. 1060-1063.

- My first five years in science. In: Nature . London 371 (1994), No. 6492, ISSN 0028-0836 , p. 10.

( A selection of publications about him as a reprint in PDF format can be found here )

Textbooks

- The nature of the chemical bond. Translated by H. Noller. Verlag Chemie, Weinheim 1968, 1976 (English original 1939 and 1960), ISBN 3-527-25217-7 .

- Basics of chemistry. Translated by Friedrich G. Helfferich. Verlag Chemie, Weinheim 1956, 1973, ISBN 3-527-25392-0 .

- General Chemistry. WH Freeman, San Francisco 1949, 1970; Dover Publications, New York 1988 (original, reprint ), ISBN 0-486-65622-5 .

- with E. Bright Wilson Jr .: Introduction to Quantum Mechanics with Applications to Chemistry. McGraw-Hill, New York 1935; Dover Publications, New York 1963, 1985, ISBN 0-486-64871-0 .

Books on Vitamin C

-

Vitamin C and the common cold . Translated by Friedrich G. Helfferich. Verlag Chemie, Weinheim 1972 (English original 1970), ISBN 3-527-25458-7 .

- Vitamin C, the Common Cold and the Flu. San Francisco 1976.

- The vitamin program. Goldmann Verlag, Munich 1990, 1992, ISBN 3-442-13648-2 .

Political Writings

- Linus Pauling: Life or Death in the Atomic Age . Illustrated by Roger Hayward, translated by Hildburg Braun. Sensen, Vienna 1960 ( DNB 453718329 ); Structure, Berlin 1964 ( DNB 453718337 ).

- Linus Pauling: New Morals and International Law. Two speeches. Union-Verlag VOB, Berlin 1970 (The lecture on the Nobel Prize: "The Nobel Lecture" and "The Leipzig Lecture", DNB 457776498 ).

literature

- Anthony Serafini: Linus Pauling - A Man and His Science . Paragon House, New York NY 1989, ISBN 0-913729-88-4 .

- Barbara Marinacci (Ed.): Linus Pauling in His Own Words. Selections from His Writings, Speeches, and Interviews . Touchstone Books, Simon & Schuster, New York 1995, ISBN 0-684-80749-1 .

- Bernhard Kupfer: Lexicon of Nobel Prize Winners . Patmos, Düsseldorf 2001, ISBN 3-491-72451-1 .

- The 100 of the century. Natural scientist. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-499-16451-5 , p. 150f.

- Clifford Mead, Thomas Hager (Ed.): Linus Pauling - scientist and peacemaker. Oregon State University Press, 2001.

- Tom Hager: Force of the nature: the life of Linus Pauling. New York 1995.

- Tom Hager: Linus Pauling and the chemistry of life. Oxford UP, 1998.

- Jack D. Dunitz : Linus Pauling. Biographical Memoirs National Academy, ( nasonline.org PDF).

- Ralf-Dieter Hofheinz: Pauling, Linus. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 1115.

documentary

- Linus Pauling. (Additional title 2011: A look back at our century - On the International Year of Chemistry . ) Documentary film, Germany, 1994, script and direction: Andrea and Harald von Troschke, production: WDR , with archive material and interview recordings between 1991 and 1993, summary of the ARD .

Web links

- Linus Pauling Institute

- Literature by and about Linus Pauling in the catalog of the German National Library

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1954 award ceremony for Linus Carl Pauling (English)

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1962 award ceremony for Linus Carl Pauling (English)

- Linus Pauling - Appreciation

- Scans of 46 of Pauling's notebooks from 1922 to 1994

- Linus Pauling: The Nature of the Chemical Bond

- The Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers at the Oregon State University Libraries

- Creating The Pauling Catalog and The Pauling Catalog

- Pauling, Oral History Interview 1964, AIP , with John Heilbron

- Pauling, Oral History Interview 1984, Caltech

- Linus Pauling in the Theoretical Chemistry Genealogy Project

- Wolfgang Burgmer: August 19, 1994 - Anniversary of the death of the chemist Linus Pauling WDR ZeitZeichen on August 19, 2014. (Podcast)

supporting documents

- ↑ Linus Pauling, Daisaku Ikeda: A Lifelong Quest for Peace: A Dialogue. Jones & Bartlett, 1992, ISBN 0-86720-277-7 , p. 22.

- ↑ Lukas Mihr: Without God everything is allowed? - Atheist "heroes". In: Humanistic press service. August 5, 2011.

- ↑ Clifford Mead, Thomas Hager (Ed.): Linus Pauling - scientist and peacemaker. Oregon State University Press, 2001, p. 153.

- ↑ Clifford Mead, Thomas Hager (Ed.): Linus Pauling - scientist and peacemaker. Oregon State University Press, 2001, p. 159.

- ↑ Clifford Mead, Thomas Hager (Ed.): Linus Pauling - scientist and peacemaker. Oregon State University, Press 2001, p. 154.

- ↑ https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1962/ceremony-speech/

- ↑ Bas Kast: Linus Pauling: A lot of vitamin C for the noble spirit. Der Tagesspiegel , February 27, 2001, accessed on January 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Harald Martenstein: Linus Pauling: A lot of vitamin C for the noble spirit. Die Zeit , April 26, 2012, accessed on January 23, 2020 .

- ^ Paul A. Offit : The Vitamin Myth: Why We Think We Need Supplements . In: The Atlantic. (Online edition), July 19, 2013. (Excerpt from Paul A. Offit: Do You Believe in Magic ?: The Sense and Nonsense of Alternative Medicine? Harper, New York 2013)

- ↑ Vitamin C fed up . in the archive of time. In: The time . No. 28 , July 7, 1993, pp. 2 ( zeit.de [accessed on May 25, 2014]).

- ↑ Heather Rock Woods: BUSINESS: Linus Pauling Institute to leave town In: Palo Alto online , January 12, 1996.

- ↑ Linus Pauling Biographical Timeline In: Linus Pauling Institute

- ↑ Goertzel and Goertzel, p. 247.

- ^ Prices from Pauling, Oregon State Library .

- ↑ Member entry of Linus Pauling (with picture) at the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina , accessed on May 24, 2016.

- ^ Members of the American Academy. Listed by election year, 1900-1949 ( amacad.org PDF). Retrieved October 8, 2015

- ↑ Jörg Melzer: 4.3.2 International Society for Food and Vital Substance Research (IVG) In: Whole Foods : Dietetics, Naturopathy, National Socialism, Social Claims , Franz Steiner Verlag , Stuttgart 2003; P. 307. ISBN 3-515-08278-6 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pauling, Linus |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Pauling, Linus Carl (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American chemist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 28, 1901 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Portland , Oregon |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 19, 1994 |

| Place of death | Big Sur , California |