Fritz Haber

Fritz Jakob Haber , also Fritz Jacob Haber (born December 9, 1868 in Breslau , † January 29, 1934 in Basel ) was a German chemist and Nobel Prize winner for chemistry . As founding director, he headed the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Berlin , which is now named after him, for 22 years . His scientific work includes contributions to thermochemistry , organic chemistry , electrochemistry and technical chemistry . Together with Max Born , Haber developed the Born-Haber cycle for the quantitative determination of the lattice energy in crystals .

Haber's attempts with phosgene and chlorine gas shortly after the beginning of the First World War made him the "father of the gas war ". Under his leadership, the German gas troops were formed and later, for the first time, poison gas was used as a weapon of mass destruction . He later explored the possibilities of extracting gold from seawater to finance German reparations payments after the First World War .

Together with Carl Bosch , he developed the Haber-Bosch process for the catalytic synthesis of ammonia from the elements nitrogen and hydrogen . This enables the mass production of nitrogen fertilizers and thus secures the nutrition of a large part of today's world population. For this he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918.

After the takeover of the Nazis Fritz Haber emigrated because of reprisals because of his Jewish ancestry in 1933 to England. A few months later he died in a hotel in Basel.

Life

Before the First World War

Fritz Haber was born as the son of the Jewish couple Paula (1844–1868) and Siegfried Haber (1841–1920) in Breslau . His father ran a business in fabrics , paints , varnishes and drugs . Serious complications occurred at birth and his mother, a distant relative of the father, died three weeks later. Fritz was brought up "lovingly" by his second wife, Siegfried Habers, his stepmother Hedwig Hamburger (1857–1912), together with the three half-sisters Else, Helene and Frieda. The contrast between the temperaments of the father, “a completely unimaginative businessman”, and the son “of a sparkling, carefree temperament” led to unbridled tensions between the two in later life.

Haber first attended the humanistic Johannesgymnasium Breslau and up to the Abitur the high school St. Elisabeth with an ancient language and mathematical orientation, chemistry was not planned as an independent subject. After completing a commercial apprenticeship , Fritz Haber studied with Robert Wilhelm Bunsen in Heidelberg from 1886 . In Heidelberg he joined a student union , the Natural Science Association of Students, which merged with the black club Karlsruhensia Heidelberg in Miltenberger Ring after the First World War . He then moved to Berlin to study with August Wilhelm von Hofmann at the Friedrich Wilhelms University . Here he was also active in the Academic and Scientific Association . He joined the working group Carl Liebermann , where he in organic chemistry on his dissertation Over some derivatives of piperonal Customized and in 1891 a doctorate was. He continued his studies first at the ETH Zurich in the working group of Georg Lunge , a friend of the Haber family, and in Jena with Ludwig Knorr . His attempts to be accepted as an assistant in Wilhelm Ostwald 's working group failed, however.

After brief activities in the chemical industry and at universities, Haber took up an assistant position at the Institute for Physical Chemistry at the Technical University of Karlsruhe in 1894 and completed his habilitation there in 1896. Two years later he published the textbook Grundriß der Praxis Elektrochemie and was in Appointed associate professor for technical chemistry in Karlsruhe in 1898 .

In 1901 Haber married Clara Immerwahr , the first female chemist to receive a doctorate in Germany, whom he had already met during his high school graduation. The following year the marriage gave birth to their son Hermann Haber. When Haber, as department head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, took on scientific responsibility for the entire war gas system during the First World War , his wife Clara Immerwahr publicly disapproved of his undertakings.

From 1904 Haber dealt with the catalytic formation of ammonia , which ultimately led to the development of the Haber-Bosch process . For this invention, Haber was subsequently awarded the 1918 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The award ceremony, announced in November 1919, met with criticism especially in France and Belgium, whose press considered the honor of the “inventor of the gas war” to be scandalous. In Sweden, it was highlighted that Haber's award-winning discovery of the synthesis of ammonia enabled Germany to wage war for so long. Scientists from the Allied and Associated States recalled Haber's signing of the Manifesto of 93 in 1914. Such considerations, however, did not play a role in the nomination of the Nobel Prize Committee. This process followed its own rules, and Haber had been nominated every year since 1912. Carl Bosch received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1931.

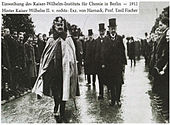

In 1905 his textbook Thermodynamics of Technical Gas Reactions was published, which contained the basis for later thermochemical work. In 1906 he was appointed to the chair of physical and electrochemistry in Karlsruhe as the successor to Max Le Blanc . In 1911 Haber was appointed founding director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Berlin-Dahlem and full honorary professor for physical chemistry at the University of Berlin . Under Haber's leadership, the institute achieved an international reputation in many areas of natural science, where important research results such as the discovery and the pure preparation of para-hydrogen by Karl Friedrich Bonhoeffer and Paul Harteck were achieved. Today this institute is named after him as the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society . From 1914 to 1915 Haber was also chairman of the German Physical Society , into which he was admitted in 1909.

Planner of the gas war in World War I.

Haber volunteered when war broke out in 1914 and worked as a scientific advisor in the War Ministry with research on the saving or manufacture of explosives and the development of new production processes for the synthesis of substitutes for raw materials essential to the war effort, the so-called "war chemicals" such as saltpeter, which was imported from Chile by the British The sea blockade had come to a standstill.

Haber's research made it possible to use the poison gases chlorine and phosgene as weapons of war in the First World War . If the original aim was to develop an irritant gas that was supposed to be a side effect of an otherwise fully functional explosive projectile, the chief of the general staff , Erich von Falkenhayn , had instructed the chemists in December 1914 to find a substance that would make people permanently incapacitated. Haber advised the Supreme Army Command of chlorine , which was to be blown off at the enemy from steel bottles. He apparently attached a tactical value to the gas weapon, which was supposed to bring movement to trench warfare, shorten the war and thus save human lives. However, poison as a weapon of war had been banned since 1899 by the Hague Land Warfare Regulations , which the German Reich had ratified in 1910. According to his plan and under his supervision, a special force for gas combat was formed in early 1915 , from which the pioneer regiments No. 35 and 36 emerged. James Franck , Otto Hahn , Gustav Hertz , Wilhelm Westphal , Erwin Madelung and Hans Geiger served in the guest groups .

From February 1915 onwards, Haber personally supervised the preparations for the first German gas attack near Ypres . He himself determined the places where the gas bottles should be buried. On April 22, 1915 at around 6 p.m. the attack took place at the start of the Second Battle of Flanders . A total of 150 tons of chlorine gas were used according to the so-called Haber's blowing process. Haber was apparently promoted to captain a few days later when the OHL decided to expand the gas weapon and entrusted Haber with it. According to historian Margit Szöllösi-Janze , chemical warfare took on a new quality with Haber's commitment. "With the first German chlorine gas attack [...] Haber [...] undoubtedly opened the history of modern chemical weapons. Gas became the first means of mass destruction in world history ”.

When he took on scientific responsibility for the entire war gas system as a department head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society during the First World War , his wife Clara Immerwahr publicly disapproved of his undertakings as a "perversion of science". On May 2, a few days after the first use of poison gas, his wife shot herself, probably in protest against her husband's activities, with Haber's service weapon on the morning after the victory ceremony in the garden of the shared house.

After the First World War, Haber was temporarily wanted by the Allies as a war criminal because he violated the Hague Land Warfare Regulations and temporarily fled to Switzerland . In 1917 Fritz Haber married his second wife, Charlotte Nathan, General Secretary of the German Society in 1914 . From this marriage a daughter, Eva Charlotte, and a son, Ludwig Fritz Haber , emerged. In 1927 the marriage was divorced again.

Life after the First World War

In April 1917 Haber founded a technical committee for pest control , which Walter Heerdt took over as head. The employees of TASCH carried out fumigation of grain silos, military installations and border crossings with hydrogen cyanide. Before the dissolution of TASCH, Haber initiated the founding of the German Society for Pest Control (Degesch) in order to make the methods of pest control with hydrogen cyanide generally accessible. He made a significant contribution to the institutionalization of pest control as a separate branch of industry. For Degesch, which has now been taken over by Degussa , Haber's employees Ferdinand Flury and Albrecht Hase developed a preparation made of cyanogen and chlorine compounds, which was patented in 1920 under the name “Zyklon”. Heerdt, Bruno Tesch and other chemists developed the product into Zyklon B further. After Haber's death, from 1942 onwards, Zyklon B was used by the National Socialists for mass murder on an industrial scale of Jews and other victims.

From 1919 onwards Haber tried in vain for six years to extract gold from the sea in order to pay the German reparations . To this end, he took part in a Hapag ship expedition from Hamburg to New York in July 1923 . Although no economical process for gold extraction was found, the detection methods could be extremely improved. The detection limit has been improved to 1 ng gold per kilogram.

Fritz Haber had been on IG Farben's supervisory board since it was founded in 1925 . In 1926 he was elected a member of the Leopoldina . After traveling to Japan , Fritz Haber was instrumental in founding the Japan Institute in 1926. This should serve to build up and maintain relations between Germany and Japan in the scientific and cultural field. Between 1922 and 1933 he was a member of the Senate of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science .

After the National Socialists had enforced the Aryan paragraph at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes in 1933 and dismissed the Jewish employees, which he could not prevent, Haber retired in May 1933. In the late autumn of 1933 he emigrated to Cambridge after receiving a professorship at the university there. Soon afterwards he accepted an offer from Chaim Weizmann to take over the management of what is now the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot , in what was then Palestine, now Israel. On the journey there, Haber died of heart failure on January 29, 1934 at the age of 65 in a hotel in Basel. His urn was buried in the local Hörnli cemetery. In 1937 the urn of his first wife Clara was reburied in Fritz Haber's grave at the instigation of her son. When a memorial service for Haber was held in the Harnack House on January 29, 1935, the Minister of Education Bernhard Rust forbade the participation of state employees and civil servants and thus of many professorial colleagues. The Association of German Chemists also banned its members from participating. Many sent their wives instead, some defied the ban. ( Otto Hahn , Richard Willstätter , Lise Meitner , Max Delbrück , Fritz Straßmann and Hermann Franz Mark took part). Carl Bosch appeared with all available directors of IG Farben. Karl Friedrich Bonhoeffer was not allowed to take part and had his memorial speech read out by Otto Hahn.

plant

Fritz Haber worked in many areas of chemistry and as a science manager. In addition to his scientific research, he appeared as an inventor. So he gave Kaiser Wilhelm Wilhelm Institute Kaiser in 1912, shortly after the opening of a warning device for the occurrence of the job, firedamp to construct. Within a year Haber developed the so-called firedamp whistle and presented it to the emperor in a lecture on October 28, 1913.

Work on electrochemistry

Fritz Haber began his scientific career investigating electrochemical methods, for example the question of the oxidation and reduction of organic substances such as nitrobenzene to phenylhydroxylamine . In addition to the technical aspects such as the representation of chemicals, he investigated fundamental electrochemical processes such as the effect of polarization and electrode potential on chemical processes. Between 1902 and 1908 Haber published various electrochemical treatises, for example on electrochemical metal deposition or the carbon element.

In addition to the basic electrochemical investigations, he devoted himself to the investigation of technical problems such as the anodic corrosion of underground pipes. He developed so-called tactile electrodes for data collection and suggested passivation with protective oxide layers as a solution to the problem.

Ammonia synthesis

It has been known since the mid-19th century that nitrogen uptake is one of the foundations for the development of crops . It was known that the plant does not take up elemental nitrogen from the atmosphere, but from nitrate , for example . Speaking to the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1898, its president, Sir William Crookes , expressed concern that civilized nations were at risk of insufficient food production. At the same time, he showed a possible solution, the so-called fixation of nitrogen from the air at the time. He called this one of the great discoveries awaiting the ingenuity of chemists. It was foreseeable that the natural occurrences of Chile's nitrate would not be able to meet the constantly increasing demand for nitrogen fertilizers. Crookes' speech met with broad approval, and the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen into a compound that plants can absorb, easily defined as “bread made from air”, became one of the main research areas of the time.

Fritz Haber began experiments on ammonia synthesis in 1904 (later named the Haber-Bosch process after him ). The equilibrium constant found for the synthesis from the elements nitrogen and hydrogen corresponded to a yield of less than 0.01% at a temperature of 1000 ° C. and normal pressure and was therefore too low for a technical process. Only at temperatures below 300 ° C and a suitable catalyst did he consider the transfer to technology possible. Due to the expected difficulties, he temporarily stopped work in this area.

On October 13, 1908, the researcher applied to the Imperial Patent Office in Berlin for patent protection for a “method for the synthetic preparation of ammonia from the elements”, which was granted on June 8, 1911 with patent no. 235,421. In the meantime, Haber had signed an employee contract with BASF and gave it the patent for commercial exploitation. Subsequently, in 1909, together with Carl Bosch at BASF, he developed the Haber-Bosch process , for which a patent was applied for in 1910. This process enabled the synthetic production of ammonia as a raw material for the production of saltpetre for the production of fertilizers and explosives . In 1913, BASF commissioned a plant based on the Haber-Bosch process at the Ludwigshafen-Oppau plant for the first time.

Born-Haber cycle

After the war, Haber devoted himself to pure research, especially the development of new models for the structure of solids . The physicist and later Nobel laureate in physics, Max Born , who often visited James Franck at the institute, was initially skeptical about Haber because of his involvement in the gas war. Haber won his trust and they agreed on a collaboration that ultimately led to the development of the Born-Haber cycle . Born had already researched crystal lattice energy with Alfred Landé . At this time Haber had made his first attempts to calculate the macroscopic properties of crystals.

In the course of their collaboration, Born and Haber developed a cycle to analyze the overall enthalpy of formation of an ion crystal from the sum of the energies of the necessary sub-steps such as the ionization energy and the enthalpy of vaporization . With the help of the Born-Haber cycle it is possible to calculate the lattice energy that can not be directly determined . The cycle in its original form is suitable for calculating the lattice energy of predominantly ionic substances such as many alkali halides , in which a covalent bond component can be neglected.

Gold from sea water

In 1920, Haber announced to a small group of employees that he wanted to do extensive research in the field of gold extraction from seawater . After the First World War, Haber saw the reparations claims of the victorious powers of over 200 billion gold marks threatened both Germany and the continuation of constructive scientific activities at his institute. Haber knew of some literature on gold extraction processes. He discussed the subject with Svante Arrhenius , whom he visited for the Nobel Prize in Stockholm. Based on the then assumed gold concentrations of three to ten milligrams per cubic meter of seawater, Arrhenius calculated a total content of up to eight billion tons of gold in seawater. In contrast, the total world gold production in 1920 was only 507 tons. The extraction of a very small part of this gold supply would have been enough to pay the German reparation costs.

After extensive preparatory work in the laboratory, Haber decided to use the cupellation process for gold extraction. To finance his project, he won Degussa and Frankfurter Metallbank. Since the precious metal was already in dissolved form, the prerequisites for a separation from the sea water seemed to be favorable, because the digestion of the gold was the most expensive step in conventional processes.

Around 5,000 samples of seawater were examined in the course of the project. The concentrations found were always 100 to 1000 times below the expected concentration. An economic extraction of gold was not possible at these low concentrations. In 1926, Haber therefore ended the search “for the dubious needle in the haystack”.

Japan Institute

Fritz Haber traveled to Japan in 1924 on the official order of Reich President Friedrich Ebert to establish contacts in the scientific and cultural fields. He was supported by Wilhelm Solf , the German ambassador in Tokyo from 1920 to 1928. This promoted together with the Japanese politicians Gotō Shinpei , among other things in Berlin with Robert Koch and at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich with Max von Pettenkofer studied had, the cultural, political and scientific rapprochement between Japan and Germany.

Haber's visit gave rise to the idea of setting up a cultural institute in Berlin and Tokyo . This was in the year after his visit on May 18, 1925 in Berlin as "Institute of mutual knowledge of the spiritual life and public institutions in Germany and Japan ( Japan Institute ) e. V. ”and opened in December 1926 with the support of Adolf von Harnack in the rooms of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in the Berlin Palace. In return, the German cultural institute was opened in Tokyo in June 1927. The aim of the institutes was to promote cooperation between Germany and Japan in the fields of business, culture and science, for example through lectures and publications.

Representation of Haber in films and literature

The life story of Fritz Haber in the field of tension between the blessing of research for the well-being of mankind and the invention of chemical weapons, the friendship of the Nobel Prize winner with Albert Einstein , the suicide of his wife, the conversion from Jewish to Christian faith and his ardent German-national patriotism and the expulsion by the Nazi regime because of his Jewish descent have been described many times.

In 1969 the writer Hermann Heinz Wille published the novel Der Januskopf about the life of Fritz Haber. In 2003 the Canadian playwright Vern Thiessen wrote a fictional life story of Haber under the title Einstein's Gift . Haber is portrayed as a tragic figure who tries unsuccessfully to evade both her Jewish ancestry and the moral consequences of her scientific contributions. The BBC radio broadcast two episodes from Haber's life. The first episode, Bread from the Air, Gold from the Sea, aired the station in 2001. It dealt with Haber's services to his fatherland and the later expulsion by the Nazis due to his Jewish descent. A second episode, The Greater Good, broadcast in 2008, focused on his work during World War I and the suicide of his wife. In 2005, a French publisher published a four-volume comic series on the life of Fritz Haber.

The director Daniel Ragussis shot the short film Haber in 2008 with Christian Berkel and Juliane Köhler in the leading roles, which won several awards. In the same year the film Einstein and Eddington appeared, in which Haber was played by Anton Lesser . In 2013 the play Fritz Haber German or Is Chemistry Right? At the Darmstadt State Theater . premiered by Peter Schanz . In 2014 the TV drama Clara Immerwahr by director Harald SICHERITZ appeared with Katharina Schüttler in the title role and Maximilian Brückner as Fritz Haber. The film describes the life of Clara Immerwahrs from high school to her suicide due to the development of the world war and her rejection of the poison gas development of her husband and work colleague Haber.

honors and awards

Designations

In his honor, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry was renamed the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society. The library of the Weizmann Institute is named after Haber, and the Fritz Haber Center for Molecular Dynamics was founded at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1981.

The Haber moon crater is named after him.

Awards

- Foreign member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1914)

- Liebig commemorative coin of the Association of German Chemists (1914)

- Corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences (1917)

- Member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences (corresponding member since 1918, foreign since 1927)

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1918)

- Bunsen Medal of the German Bunsen Society for Physical Chemistry , together with Carl Bosch (1918)

- President of the Society of German Chemists (1923)

- Harnack Medal of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (1926)

- Wilhelm Exner Medal (1929)

- Honorary member of the Société Chimique de France (1931).

- Honorary member of the Chemical Society of England (1931).

- Honorary member of the Society of Chemical Industry, London, (1931).

- Rumford Medal , American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1932)

- Foreign member of the National Academy of Sciences , USA (1932)

- Honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1932)

- Chairman of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry , 1929-1933; Vice President, 1931

- Goethe Medal for Art and Science

The German Bunsen Society for Physical Chemistry has been awarding the “Nernst-Haber-Bodenstein Prize” since 1959 for outstanding scientific achievements by young researchers in the field of physical chemistry .

Works

- Ground plan of technical electrochemistry on a theoretical basis. R. Oldenburg, Munich 1898.

- Thermodynamics of technical gas reactions. R. Oldenburg, Munich 1905.

- with E. Ramm, N. Caro: From air through coal to nitrogen fertilizer, bread and plenty of food. R. Oldenburg, Munich 1920.

- Five lectures from the years 1920–1923. J. Springer, Berlin 1924. New edition under the title: The Chemistry in War - Five Lectures (1920–1923) on poison gas, explosives and artificial fertilizers in the First World War. Comino, Berlin 2020, ISBN 978-3-945831-26-7 .

- From life and work. Essays, speeches, lectures. J. Springer, Berlin 1927.

literature

- Jörg Albrecht : Bread and wars from the air. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung . 41/2008, p. 77.

- Jo Angerer: Chemical weapons in Germany. Abuse of science. Luchterhand, Darmstadt 1985, ISBN 3-472-88021-X .

- Ute Deichmann : To the fatherland - as long as it wishes. Fritz Haber's resignation in 1933, death in 1934 and the Fritz Haber commemoration ceremony in 1935. In: Chemistry in our time . Vol. 30, No. 3, 1996, pp. 141-149, doi: 10.1002 / ciuz.19960300306 .

- Magda Dunikowska, Ludwik Turko: Fritz Haber: The Damned Scientist. In: Angewandte Chemie. International Edition. 50, 2011, pp. 10050-10062. German edition in: Angewandte Chemie. 123, 2011, pp. 10226-10240, doi: 10.1002 / anie.201105425 .

- Adolf-Henning Frucht , Joachim Zepelin: The tragedy of spurned love. In: Mannheimer Forum 1994/95. Piper, Munich 1995.

- Adolf-Henning Frucht: Fritz Haber and pest control during the 1st World War and in the inflationary period. In: Dahlem Archive Talks. Volume 11, 2005, pp. 141-158.

- Ralf Hahn: Gold from the Sea - The research of Nobel Prize winner Fritz Haber in the years 1922–1927. GNT-Verlag, Diepholz 1999, ISBN 3-928186-46-9 .

- Erna and Johannes Jaenicke: Haber, Fritz Jacob. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1966, ISBN 3-428-00188-5 , pp. 386-389 ( digitized version ).

- Gerhard Kaiser : How culture collapsed. Poison gas and the ethos of science in the First World War. In: Mercury . 56, 2002, issue 635, pp. 210–220, urn : nbn: de: bsz: 25-freidok-5065 .

- Hans-Erhard Lessing : Bread for the World, Death to the Enemy. in: Stephan Leibfried et al. (Ed.): Berlin's wild energies - portraits from the history of the Leibniz Science Academy. de Gruyter, Berlin, 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-037598-5

- Christof Rieber: Albert Einstein. Biography of a nonconformist. Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2018, ISBN 978-3-7995-1281-7

- Fritz Stern : Five Germanys and one life: memories. Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-55811-5 .

- Dietrich Stoltzenberg: Fritz Haber: Chemist, Nobel Prize Winner, German, Jew. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 1998, ISBN 3-527-29573-9 .

- Margit Szöllösi-Janze : Fritz Haber. 1868-1934. A biography. Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 .

- Stefan L. Wolff: As a chemist among physicists. The chemist Fritz Haber (1868–1934) also played an important role in physics. In: Physics Journal . Vol. 17, 2018, pp. 30–34 ( article in Researchgate, with download option )

- Stefan L. Wolff: Fritz Haber's last official act. In: Culture and Technology. Vol. 43, 2019, issue 3, ISSN 0344-5690 , pp. 56-59.

Web links

- Literature by and about Fritz Haber in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Fritz Haber in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- A short biography of Fritz Haber, by Bretislav Friedrich (English; PDF; 3.12 MB)

- Reich Chancellery files Fritz Haber at the Federal Archives

- Hans-Volkmar Findeisen: Audio feature about the life and work of Fritz Haber. (mp3) (No longer available online.) In: podster.de. Media library on SWR2 Knowledge Department, archived from the original on July 15, 2014 (focus: poison gas research).

- Irene Meichsner : Fritz Haber - "Father of the Gas War". (mp3; 4:58 min.) Born 150 years ago. In: deutschlandfunk.de. Deutschlandfunk , December 10, 2018 ( calendar sheet series ).

- Sven Preger: December 9th, 1868 - birthday of the chemist Fritz Haber. WDR ZeitZeichen from December 9, 2018 (Podcast)

Individual evidence

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 26.

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 26 f. The immediate departure from Wroclaw after the age of majority and the conversion to the Protestant faith, according to Szöllösi-Janze, can be interpreted as a sign of the distancing of the son from the father.

- ^ List of famous corporates. In: frankfurter-verbindungen.de. Retrieved July 5, 2014 .

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 44.

- ↑ Fritz Haber's biography. In: Nobelprize.org. Retrieved July 5, 2014 .

- ↑ Fritz Haber: About some derivatives of the piperonal. In: Reports of the German Chemical Society. 24, 1891, pp. 617-626.

- ^ Bretislav Friedrich: Fritz Haber: Chemist, Nobel Laureate, German, Jew. By Dietrich Stoltzenberg. In: Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 44, 2005, pp. 3957-3961, doi: 10.1002 / anie.200485206 .

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , pp. 124–125: “According to Charlotte Haber, followed by Leitner, the high school graduate wanted to marry his former love of dancing lessons and then pursued this plan tenaciously, against the fierce resistance of the Father. "

- ↑ F. Haber, R. Le Rossignol: About the ammonia equilibrium. In: Reports of the German Chemical Society. 40, 1907, pp. 2144-2154, doi: 10.1002 / cber.190704002129 .

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. CH Beck, Munich 1998, pp. 430-435.

- ↑ The discovery of para-hydrogen. In: mpibpc.mpg.de. Retrieved November 16, 2014 .

- ↑ on this activity see Stefan L. Wolff: Als Chemiker unter Physikern. The chemist Fritz Haber (1868–1934) also played an important role in physics . In: Physics Journal. Vol. 17, 2018, pp. 30–34

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 257.

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , pp. 268-271.

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 324.

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 327.

- ↑ Art. 23 point a) i. d. Fassg. V. 1907

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 328.

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 329 f.

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , pp. 329-331.

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 317.

- ↑ Gerit von Leitner : The case of Clara Immerwahr. Living for a humane science. 2nd Edition. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-406-38256-8 .

- ↑ Peter Hayes: Degussa in the Third Reich. From cooperation to complicity. CH Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-52204-1 , p. 284 f.

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze : Fritz Haber. 1868-1934. A biography. Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 456.

- ↑ Peter Hayes: Degussa in the Third Reich. From cooperation to complicity. CH Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-52204-1 , p. 285 f.

- ↑ Michael Berenbaum: Holocaust. European history. In: Encyclopædia Britannica online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., January 14, 2020, accessed June 28, 2020, archived version .

- ↑ F. Haber: The gold in sea water. In: Journal for Applied Chemistry. 40, 1927, pp. 303-314, doi: 10.1002 / anie.19270401103 .

- ↑ Max von Laue: Fritz Haber. In: The natural sciences. 22, 1934, pp. 97-97, doi: 10.1007 / BF01495380 .

- ↑ a b Ulrike Kohl: The presidents of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in National Socialism: Max Planck, Carl Bosch and Albert Vögler between science and power. Steiner, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-515-08049-X , pp. 92-94.

- ^ Klaus Beneke: Hermann Franz Mark: co-founder of polymer science. University of Kiel, January 2005, p. 11 ( PDF; 2.6 MB ).

- ↑ Fritz Haber: About the electrolytic reduction of the nitro bodies. In: Angewandte Chemie. 13.18, 1900, pp. 433-439, doi: 10.1002 / ange.19000131802 .

- ^ Fritz Haber, Ludwik Bruner: The carbon element, an oxyhydrogen chain. In: Journal of Electrochemistry and Applied Physical Chemistry. 10.37, 1904, pp. 697-713, doi: 10.1002 / bbpc.19040103702 .

- ↑ Georg v. Hevesy, Otto Stern: Fritz Haber's work in the field of physical chemistry and electrochemistry. In: Natural Sciences. 16, 1928, pp. 1062-1068, doi: 10.1007 / BF01507091 .

- ↑ F. Haber, G. van Oordt: About the formation of ammonia the elements. In: Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 44, 1905, pp. 341-378, doi: 10.1002 / zaac.19050440122 .

- ^ William Crookes: The Report of the 68th Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. London / Bristol 1898.

- ↑ Gerhard Ertl: "Bread from Air" - On the mechanism of the Haber-Bosch process . In: Akademie-Journal . No. 1 , August 2003, p. 14-18 ( PDF ).

- ^ Bretislav Friedrich: Fritz Haber: Chemist, Nobel Laureate, German, Jew. By Dietrich Stoltzenberg. In: Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 44, 2005, pp. 3957-3961, doi: 10.1002 / anie.200485206 .

- ↑ Patent DE235421 : Process for the synthesis of ammonia from the elements. Registered October 13, 1908 , published June 8, 1911 . Applicant: Baden Aniline and Soda Factory, inventor Baden Aniline and Soda Factory

- ^ Günther Luxbacher: bread and explosives. ( Memento from February 2, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) In: EXTRA Lexikon, Wiener Zeitung .

- ^ A b c Bretislav Friedrich, Dieter Hoffmann, Jeremiah James: One Hundred Years of the Fritz Haber Institute. In: Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 50, 2011, pp. 10022-10049, doi: 10.1002 / anie.201104792 .

- ↑ Erwin Riedel: Inorganic Chemistry. de Gruyter, 2004, ISBN 3-11-018168-1 , p. 91.

- ↑ a b c d Johannes Jaenicke: Haber's research on gold deposits in sea water. In: The natural sciences. 23, 1935, pp. 57-63, doi: 10.1007 / BF01497020 .

- ↑ United States Geological Survey: World Production (PDF; 38 kB).

- ↑ Fritz Haber: The gold in sea water. In: Journal for Applied Chemistry. 40, 1927, pp. 303-314, doi: 10.1002 / anie.19270401103 .

- ^ Rolf Brockschmidt: A bridge between Japan and Europe. In: Weltspiegel. November 8, 1987, accessed December 18, 2014 .

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. 1998, p. 575.

- ↑ See data set in the German National Library: DNB 458655910 .

- ^ Bread from the Air, Gold from the Sea. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on February 2, 2009 ; Retrieved December 19, 2014 .

- ^ Fritz Haber 1. L'Esprit du temps. In: editions-delcourt.fr. Retrieved December 27, 2014 .

- ↑ Haber (2008). In: The Internet Movie Database. 2008, accessed June 27, 2014 .

- ↑ Michal Meyer: Feeding the War. In: Chemical Heritage Foundation. Retrieved December 18, 2014 .

- ^ Einstein and Eddington (2008) (TV). In: The Internet Movie Database. 2008, accessed September 18, 2008 .

- ↑ Fritz Haber German or is the chemistry correct? (No longer available online.) Staatstheater Darmstadt , archived from the original on November 13, 2017 ; accessed on July 23, 2017 .

- ^ Bretislav Friedrich: Fritz Haber: Chemist, Nobel Laureate, German, Jew. By Dietrich Stoltzenberg. In: Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 44, 2005, pp. 3957-3961, doi: 10.1002 / anie.200485206 .

- ↑ Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter B. (PDF; 709 kB) (No longer available online.) In: amacad.org. American Academy of Arts and Sciences, archived from the original on October 20, 2018 ; accessed on November 15, 2014 .

- ↑ Holger Krahnke: The members of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen 1751-2001 (= Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, Vol. 246 = Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Mathematical-Physical Class. Episode 3, vol. 50). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-82516-1 , p. 100.

- ^ Nobelstiftelsen - The Nobel Foundation: Les Prix Nobel en 1919–1920. Norstedt, Stockholm 1922, p. 38: Chemical Nobel Prize 1918 (award speech; German translation) - Internet Archive ; (Appendix) pp. 1–16: Nobel Lecture, given on June 2, 1920 in Stockholm by Fritz Haber - Internet Archive ; (Appendix) p. 121: Fritz Haber's curriculum vitae - Internet Archive .

- ^ Frank Colby: The New International Year Book: A Compendium of the World's Progress for the year 1918. Dodd, Mead and Company, 1919.

- ^ Nernst Haber Bodenstein Prize. (No longer available online.) German Bunsen Society for Physical Chemistry, archived from the original on October 22, 2015 ; Retrieved December 18, 2014 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Haber, Fritz |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Haber, Fritz Jakob (full name); Haber, Fritz Jacob (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German chemist and Nobel Prize winner for chemistry |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 9, 1868 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Wroclaw |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 29, 1934 |

| Place of death | Basel |