Carl Bosch

Carl Bosch (born August 27, 1874 in Cologne , † April 26, 1940 in Heidelberg ) was a German chemist , technician and industrialist . With the Haber-Bosch process he developed , a high-pressure process for ammonia production , he created the basis for the large-scale production of nitrogen fertilizers at BASF , which forms the basis for the food supply of a large part of the world's population.

Based on the experience with the high-pressure technology introduced by Bosch, BASF developed further high-pressure processes such as the production of methanol from carbon monoxide and hydrogen , the isobutyl oil synthesis , the urea synthesis from ammonia and carbon dioxide, and the Bergius Pier process for the production of synthetic motor gasoline from coal .

His diplomatic talent as a representative of the German chemical industry in the negotiations for the Versailles Peace Treaty in 1919 and his commitment to solving the food problems after the First World War made him one of the most influential personalities in the German chemical industry. Between 1919 and 1925, Bosch headed BASF as Chairman of the Board of Management and then for ten years the IG Farben Group , which was founded under his leadership and was the largest chemical company in the world at the time.

Numerous scientific societies have recognized Bosch for its work. Due to his engineering achievements in the field of high pressure chemistry in the development of the Haber-Bosch process, the Nobel Foundation awarded him the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1931 , together with Friedrich Bergius . Under pressure from the Nazi regime, Bosch gave up his position as chairman of the board in 1935 and, after Carl Duisberg's death, took over the chairmanship of the IG Farben supervisory board. As the successor to Max Planck , Bosch became President of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in 1937 . Not least because of the political developments in Germany, Bosch fell into deep depression and attempted suicide in 1939. He died a year later, on April 26, 1940 in Heidelberg.

life and work

Youth and studies from 1874 to 1899

Carl Bosch was the first of seven children of the couple Carl Friedrich Alexander Bosch (1843–1904), co-owners of the installation company Bosch & Haag in Cologne, and his wife Paula, née Liebst (1851–1930). His uncle was the industrialist Robert Bosch . Carl Bosch showed a talent for science and technology early on. He worked as a locksmith and precision mechanic in his father's company and received appropriate training. He was particularly interested in chemistry and had his own chemical laboratory in the backyard.

After graduating from the Oberrealschule in Cologne in March 1893, he began an apprenticeship in the Marienhütte in Kotzenau near Liegnitz in Silesia in order to improve his knowledge of metallurgy . He worked for a year in the molding shop, locksmith's shop and model carpentry, where he was trained as a craftsman. He then completed a degree in mechanical engineering and metallurgy at the Technical University of Charlottenburg after two years in 1896. The knowledge of metallurgy acquired during the course would later prove to be very useful for the development of the Haber-Bosch process. During his studies in Berlin, Bosch also attended lectures on chemistry from Friedrich Rüdorff , Carl Liebermann, and Otto Nikolaus Witt .

He began studying chemistry in the summer semester of 1896 at the University of Leipzig . Two years later, Bosch wrote his dissertation in organic chemistry on the condensation of disodium acetone dicarboxylic acid diethyl ester with bromoacetophenone in Johannes Wislicenus' group, where he received his doctorate summa cum laude in 1898 .

Wilhelm Ostwald , who was considered to be one of the founders of physical chemistry and whose application Bosch later made particular effort to apply , also taught in Leipzig . He recognized thermodynamics , such as the precise measurement of temperature, research into phase diagrams , and the processes of reaction kinetics as important foundations of industrial chemistry. He saw their status in these areas as underdeveloped.

In addition to studying chemistry, Bosch also devoted himself to other scientific disciplines and pursued a wide range of scientific interests in his free time. He pursued various of these interests as hobbies throughout his life. He dealt in particular with mineralogy , zoology , bacteriology and botany . In addition to entomology , where he collected and prepared butterflies and beetles himself, he dealt with the identification of plants.

First years at BASF from 1899 to 1908

After a short time as a research assistant at Wislicenus, Bosch joined BASF in 1899 on the recommendation of his doctoral supervisor . At first he worked as an employee of Rudolf Knietsch and Eugen Sapper as an operator in the phthalic acid plant , which he was commissioned to expand. Knietsch had been working on processes for producing ammonia for some time. In 1900 he entrusted Bosch with examining a patent from Wilhelm Ostwald for the preparation of ammonia from the elements nitrogen and hydrogen, which he had offered BASF. Bosch proved that the ammonia formed came from the iron nitride in the catalyst and that Ostwald's patent was based on a false assumption.

As early as 1903, the Rottweiler explosives manufacturer Max Duttenhofer had published Wilhelm Ostwald's warning of a saltpeter embargo in the event of war in "Swabian Merkur", aware of the limited stocks of Chile's nitrate ( sodium nitrate ), which was of great importance for the manufacture of fertilizers and explosives , the then chairman of the supervisory board of BASF Heinrich von Brunck commissioned Bosch in 1902 to deal with the issue of nitrogen fixation.

During this time he married Else Schilbach in May 1902. The marriage had their son Carl Jr. (1906–1995) and their daughter Ingeborg (1911–1972). First, the couple moved into a rented apartment in Ludwigshafen, which Bosch equipped with a workbench, an aquarium and a microscope so that they could pursue his passion for collecting and handicrafts. Bosch went on many excursions in the vicinity of Ludwigshafen, where he collected mussels, beetles, snails and other animals and plants. After moving to a factory apartment, he expanded his collections and created ponds in which he grew aquatic and marsh plants.

In 1904, Alwin Mittasch was assigned to him as an assistant for work on nitrogen fixation . Bosch initially focused on the indirect fixation of nitrogen through the formation of cyanides and nitrides . In his first experiments he represented nitrides of the elements barium , titanium , silicon and aluminum . The formation of barium cyanide from the elements and carbon monoxide according to

was already known.

Based on the research results from Bosch, BASF built a barium cyanide factory in 1907. The resulting cyanide could be converted into ammonia by hydrolysis . However, the yields achieved did not meet expectations and BASF closed the plant again in 1908. In 1908 Bosch began to research the formation of titanium nitride , silicon nitride and aluminum nitride . During the experiments it was found that the yield of nitrides could be improved by adding promoters , a discovery that would later play a major role in the search for an active catalyst. The nitrides should be converted into ammonia and the corresponding metal oxides in the Serpek process with water. The energy consumption of the indirect process, as well as the arc process for the direct oxidation of nitrogen developed at BASF at the time, turned out to be very high and made large-scale implementation difficult.

Development of the Haber-Bosch process from 1909 to 1913

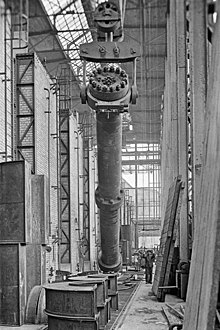

In 1909, BASF commissioned Bosch to bring the ammonia synthesis previously discovered in the laboratory by Fritz Haber , professor of technical chemistry at the Technical University of Karlsruhe, to the level of industrial production at high pressure and temperature. Based on the law of mass action it was already obvious that the use of high pressures was advantageous, but at that time there was still a lack of large-scale technical experience for working with high pressures and simultaneously high temperatures.

With the support of the Board of Management and the Supervisory Board and bypassing the competencies of the various departments, Bosch initially set up its own high-pressure workshop. At the same time, his assistant Alwin Mittasch began the systematic search for a catalyst suitable for industrial use. Initially, the search focused on catalysts for the rare and therefore expensive elements osmium and uranium . However, the experiences with promoters gained during the attempts to produce nitrides prompted Mittasch to investigate iron- based catalysts more closely. He checked various additives with regard to activation, stabilization or poisoning of the catalyst.

As early as 1910, Bosch and Mittasch filed a patent for the manufacture of catalysts based on iron. Due to the initial success in the technical implementation of the process, despite setbacks in the construction of the first reactors, the nitrogen department was founded in 1912 under Bosch's direction. Bosch had to overcome major technical problems and the development costs were very high. The department included nine chemists such as Johannes Fahrenhorst (later head of the nitrogen plant), the physicist Paul Ludwig Christoph Gmelin and 126 other employees, including many locksmiths. The then newly founded BASF ammonia laboratory was also subordinate to him.

One of the questions concerned the durability of the reactors at high hydrogen pressures and high temperatures. The steel reactors made of carbon steel could not withstand these. Bosch benefited from his experience in metallurgy and was mostly present in person during the practical trials in numerous tests. When he conducted a metallurgical examination of the steel of a burst reactor, he found that the carbon had been removed from the structure. He realized that the hydrogen had attacked the steel and the carbon had been hydrogenated. As a countermeasure, he had the carbon-containing steels lined with soft iron that contained no carbon and protected the pressure-absorbing outer jacket made of carbon-containing steel.

In addition to the diverse metallurgical and engineering issues that culminated in the development of the ammonia reactor with a double tube and the so-called Bosch holes, the question of how to provide the required hydrogen had to be solved. An annual production of 100,000 tons of ammonia per year required around half a billion cubic meters of hydrogen, which had to be compressed from 1 bar to an operating pressure of around 200 bar.

This was achieved through the development of the catalytic water gas shift reaction by Bosch and Wilhelm Wild . As a result, a higher hydrogen yield was achieved from the water gas formed during coal gasification by reacting with water. At the same time, the interfering carbon monoxide was converted into carbon dioxide, which was removed from the gas mixture by gas scrubbing.

After the various problems had been overcome, BASF began building an ammonia factory in Ludwigshafen in 1912. On September 19, 1913, this started production as the first Haber-Bosch system. The initial capacity was about 20 tons of ammonia per day, in 1914 an output of 40 tons per day was already achieved.

To study the fertilizers made from ammonia, Bosch founded the Limburgerhof Agricultural Research Institute in 1914 . There he had systematic studies carried out on the influence of various nitrogen and complete fertilizers such as ammonium nitrate , ammonium sulfate nitrate , urea , nitrophoska and calcium ammonium nitrate on plant growth. In order to convince skeptical farmers of the effectiveness of the fertilizers, Bosch had fertilized and unfertilized plants recorded over several months using time-lapse technology . The films caused a sensation and convinced many farmers of the effectiveness of the fertilizers. The cultural film “Das Blumenwunder” was later cut from the recordings and shown in cinemas across Germany.

First World War and the saltpeter promise 1914 to 1918

With the beginning of the World War in 1914, the demand for ammonia fertilizers collapsed due to the sea blockade and the resulting lack of access to the world market. The supply of nitrates for the production of explosives, on the other hand, was to be of great importance for the war economy. Despite warnings from Emil Fischer and Walter Rathenau , the General Staff did not initially recognize this connection. On the basis of the Schlieffen Plan , the basis of the German operations at the beginning of the First World War, a war of only a few weeks was planned. Only after the Battle of the Marne did the General Staff change their point of view and expect the war to last longer. Since the German nitrate reserves were almost exhausted by this time, the War Ministry turned to Carl Bosch in September 1914.

He signed a contract for the supply of nitrates, the so-called " saltpetre promise ", and switched the production of fertilizers to saltpetre . Although catalytic ammonia combustion had only been tested on a laboratory scale up to this point in time, it was possible to set up nitrate production in Ludwigshafen within a relatively short period of time. In April 1915, BASF was already producing 150 tons of nitrates per day.

As a result of the lack of Chile nitrate due to the British blockade and the inadequate capacity of the plant in Ludwigshafen-Oppau to produce ammonia for warfare in World War I, BASF began building the new ammonia plant in Merseburg on May 1, 1916 at Leuna at the suggestion of Bosch . The new plant was located near the central German lignite basin, which secured the supply of energy and raw materials. Under Bosch's direction, the Leuna works were completed in just nine months and became a member of the Board of Management of BASF in the same year. Sufficient quantities of ammonia were produced in Leuna for the military until the end of the war. By the end of 1917, production had increased to around 3,000 tons per month.

In August 1916, the already existing since 1904 Triple Alliance concluded from Agfa , BASF and Bayer with the Triple Entente Hoechst , Cassella and Kalle chemical plant with the Dr. E. ter Meer & Cie to form a 50-year interest group of German tar paint factories. The so-called “Small IG” was joined by the Griesheim-Elektron chemical factory , with the companies involved remaining legally independent.

At that time, however, the chemical industry was not able to solve the supply problems in the rubber and oil sector. The entry of the United States into the war in April 1917 solved the problems of oil and gasoline supplies for the Allies. The Armistice of Compiègne finally ended on 11 November 1918, the fighting in the First World War .

Post-war period 1919 to 1924

Armistice negotiations

After the World War, Bosch took part in the Versailles armistice negotiations as an economic advisor in 1919 . Its mission was to save the German chemical industry. The Allies demanded the surrender of the German chemical industry and the destruction of the Oppau and Leuna plants. The Oppauer plant alone had produced 90,000 tons of synthetic nitrates in the last year of the war, about a fifth of the Chile nitrate that was available to the rest of the world.

Bosch, who was dissatisfied with the Allied terms regarding the confiscated German patents and plants, traveled to Ludwigshafen during the negotiations, where he was elected Chairman of the Board of Executive Directors of BASF. After his election, he returned to Versailles to continue his efforts to weaken the Allied position.

Through negotiations with the General Inspector of the French War Ministry, General Patard, Bosch succeeded in rejecting the demands. As compensation, BASF was supposed to help build nitrate plants and provide the necessary equipment to create a successful French nitrogen industry and to manage the French dye market in the cartel with the Paris government. In return, the French withdrew their demand for the destruction of the German dye and nitrate plants.

Bosch repeatedly pointed out the necessity of the plants for the production of nitrogen fertilizers, which should help to avoid a famine. His argument was indirectly supported by the Nobel Prize Committee, as Fritz Haber was awarded the 1918 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The committee argued against the international protests and regardless of Haber's role in the gas war, that it was known that the production of nitrogen fertilizers is of global importance for increasing food production.

During the negotiations, Bosch met Hermann Schmitz , who took part in the negotiations as an expert on nitrates and fertilizers. Bosch hired Schmitz as a financial advisor, who was appointed CFO of BASF in 1919, a position that he later also took for IG Farben.

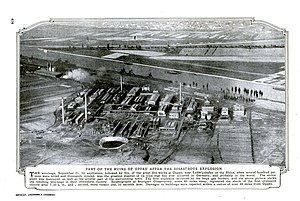

Explosion of the Oppau nitrogen works

Since 1919, BASF has been producing ammonium sulfate nitrate , a 50/50 mixture of ammonium sulfate and ammonium nitrate, as a fertilizer . This fertilizer was highly hygroscopic and agglomerated on storage. It was customary to loosen the product with small explosive charges. One of these explosions in September 1921 resulted in two huge explosions that destroyed a large part of the plant. As a result of the devastating explosion, 559 people died and more than 2000 were injured. In the neighboring village of Oppau, the homes of around 7,000 people were destroyed.

Bosch commissioned Carl Krauch to rebuild Oppau. Krauch recruited the necessary workforce in a very short time and Oppau was rebuilt in just three months. The day after Oppau was restarted, Krauch was promoted to the BASF Board of Management. Bosch himself fell ill for a long time and did not return to work until June 1922.

Ruhr occupation

After giving France an assurance that it would help set up a nitrogen industry, the American company Du Pont approached Bosch. Du Pont had recognized that, despite considerable investments, it was not possible to set up his own dye production solely on the basis of the confiscated patents. However, Bosch did not agree to a cooperation and referred to the non-consent of the other companies of the "small IG". By recruiting chemists from Bayer AG, Du Pont was able to implement the patents and compete on the world market for dyes with the companies in the interest group.

In 1922, the chemical industry had difficulties in delivering the reparations quotas required in the Versailles Treaty in the form of raw materials and finished goods, which led to the occupation of the Ruhr by French troops. The Reich government under Chancellor Wilhelm Cuno responded with a policy of passive resistance. Production in the BASF plants was shut down for about four months until May 1923. As a result, they also fell behind in delivering dyes and nitrate fertilizers for reparation payments. The inflation rate reached its highest level. Gustav Stresemann , the new Chancellor, introduced the Rentenmark and thus ended hyperinflation. He persuaded the French to withdraw from the Ruhr area against a promise to resume reparation payments. The closure of many chemical plants during the war in the Ruhr had given the American dye industry the opportunity to supply the US market on its own without German competition.

The French used the closure as a reason to terminate the contract between Patard and Bosch, as the chemicals required in the contract had not been delivered. The French now possessed the IG's technical knowledge for no further consideration. Due to the growing strength of foreign competitors since 1923, Duisberg demanded a fundamental reorganization of the international business of the IG companies.

CEO of IG Farben from 1925 to 1935

Founding of IG Farben

Carl Bosch also considered consolidating the IG companies. His goal was to use Germany's coal reserves with the help of high pressure hydrogenation as a source of motor gasoline . The fuels and lubricants made from coal appeared to Bosch to be a promising source of income due to the increasing degree of motorization , the seemingly rapidly depleted oil reserves and, in contrast, the considerable amount of brown and hard coal. He was convinced of the potential of high pressure technology. Due to the diverse scientific and technical challenges of catalyst and process development, as well as the commercial risks of carbohydrate hydrogenation, Bosch understood that the large-scale use of the process required a broader financial basis. Only a company with the financial strength of a merged IG Farben could finance the development of such a process.

Already at the beginning of the century and during the First World War, interest groups were formed in the chemical industry. Around 1904 to form the interest group of the German tar paint industry on the initiative of Carl Duisberg , the Chairman of the Board of Management of Bayer AG . The competition that grew in the 1920s convinced Duisberg of the need to reorganize the organization's activities. Bosch also supported a merger.

But while Duisberg advocated a holding structure , Bosch strove for a merger of the companies. A consolidation of production and financial strength through a merger of the large chemical industry would provide the newly formed company with the capital required to develop a coal hydrogenation process.

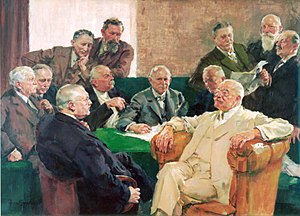

In December 1925, Bosch achieved its goal by founding the “Interest Group for the paint industry”, or IG Farben for short, by merging BASF with the companies Hoechst , Bayer, Agfa , Cassella Farbwerke Mainkur , the tar paint factories Dr. E. ter Meer & Cie and Griesheim-Elektron became the largest chemical company in the world at the time. Carl Bosch became chairman of the executive board of IGFarben and Carl Duisberg became chairman of the supervisory board.

Bergius Pier Procedure

Bosch had Hermann Schmitz covertly buy up the rights to the Bergius patents during the negotiations to form the interest group. In the 1920s, a coal liquefaction plant using the Bergius Pier method was built in Leuna . Between 1926 and 1932 IG Farben invested around 100 million marks in carbohydrate hydrogenation without being able to completely overcome the technical problems. The plant built in Leuna only delivered half of the planned output. The company needed another 400 million marks for the large-scale implementation.

Carl Bosch belonged to the German Democratic Party . Although Bosch hardly made any public statements about politics, before 1933 the IG Farben supported a number of newspapers that advocated Gustav Stresemann 's policies , as well as campaigns by the German People's Party , the German Democratic Party and the German Center Party . Wilhelm Ferdinand Kalle , board member of IG Farben, tried to unite these parties against Hitler and Alfred Hugenberg . Two IG Farben supervisory board members, Hermann Warmbold and Paul Moldenhauer from the German People's Party, were economic and finance ministers in the cabinets of Heinrich Brüning , Hermann Müller , Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher .

In the Great Depression of 1929, however, the price of gasoline fell to 5 pfennigs per liter, with production costs of around 40 pfennigs per liter. IG Farben had to drastically reduce expenses, and the number of employees was almost halved. Carl Bosch had to ask Brüning to secure the production of ammonia and fuel through protective tariffs , whereupon Brüning issued an emergency ordinance in 1931 to impose tariffs on nitrogen products and fuels.

time of the nationalsocialism

Bosch showed an ambivalent attitude towards National Socialism . At first he said of Hitler: “You only have to look at him to know” and thus expressed his rejection of Hitler. Later he again praised Hitler as "the man who was the first to clearly recognize unemployment as a cardinal problem of economic hardship and who was the only one to take measures to overcome it." In 1926 the problem prevailed in the Leuna works that the production of gasoline was more expensive than the introduction of normal gasoline. Adolf Hitler then granted protective tariffs in order to keep German gasoline competitive.

Hitler's statement that synthetic fuel is “absolutely necessary for a politically independent Germany,” commented Bosch with the words: “The man is more sensible than I thought.” In a statement titled Where there's a will, there's a way Bosch wrote in 1933 that "for the first time since the war a German government not only makes promises, but also acts". In particular, he advocated the measures to create jobs and the reduction of the tax burden.

His company profited from the self-sufficiency efforts of the German Reich. Bosch thus supported Hitler in order to secure his research financially and to advance his personal interests, and increasingly proclaimed that he valued the regime. On the other hand, no member of the IG Farben leadership was a party member of the NSDAP until 1933 . Bosch himself never joined the NSDAP.

Carl Bosch was one of the founding members of the Academy for German Law in 1933 . IG Farben, which Bosch headed as chairman of the board, supported the NSDAP in the 1933 election campaign with 400,000 Reichsmarks - the highest single donation by German industry for this party that year - in order to pave the way for the later contract for the delivery of 350,000 tons of hydrogen fuel prepare. The self-sufficiency efforts of the National Socialists for a Germany independent of raw materials and the beginning of the armaments industry promoted or saved Bosch's favorite projects, the production of synthetic rubber ( Buna ) and synthetic gasoline . IG Farben was at risk of losing 300 million Reichsmarks due to a lack of profitability.

On the other hand, Bosch was against Nazi anti-Semitism for personal and professional reasons. In 1933, several Jews were among his closest colleagues. Ernst Schwarz, Bosch's secretary since 1918, was the son of a rabbi. IG Farben's financial participation in an election fund for Hitler came about against his will. At the end of February 1933, Hermann Göring personally invited Bosch to a meeting, which he did not attend. A representative of IG Farben, who had gone to the meeting in his place, then reported to Bosch. Unexpectedly, Hitler showed up at the meeting and gave a long speech. Hjalmar Schacht then surprised the meeting by asking them to subscribe to an election fund of three million marks for Hitler. The representative of IG Farben could not be the only one to exclude himself. When Carl Bosch found out about it, he was silent and just shrugged, which was always a sign that something was displeasing to him. Afterwards, Bosch made no secret of how angry he was about this incident and how wrong he thought this support was. But he was faced with a fait accompli and couldn't change anything. In 1934, the press chief of IG Farben, Heinrich Gattineau , was arrested in the course of a “cleanup” on the occasion of the Röhm putsch . After his release from prison, Gattineau went to Bosch, who brushed off the possible termination of the employment relationship with the words “Of course you stay on your post!”.

In particular, Carl Bosch rejected anti-Semitic legislation and advocated the retention of Jewish scientists in Germany. As an industrialist with a national attitude towards Germany, Bosch did not reject the " seizure of power " at first, but made the experience that Hitler was not accessible to rational arguments. Because of this, his relationship with Hitler was not particularly good. He offered help to his colleague Fritz Haber when he was expelled in 1933 and many colleagues turned away from him. At a celebration organized by Max Planck to mark the anniversary of Haber's death in January 1935, Bosch appeared with all the available directors of IG Farben; The Reich Minister of Education Bernhard Rust forbade the academics employed at the universities to participate by decree.

Bosch did not allow all non- Aryan employees to be dismissed from IG Farben until 1937. This happened under pressure from Nazi laws, through denunciations from their own factories and out of fear of expropriation ; under Nazi race laws, a company with a single director of Jewish descent was considered a Jewish company. About a third of the supervisory board, including the brothers Carl and Arthur von Weinberg , Otto von Mendelssohn Bartholdy , Alfred Merton , Richard Merton , Ernst von Simson , Wilhelm Peltzer and Gustav Schlieper were relieved of their duties. Board members such as Carl Krauch , Fritz ter Meer , Georg von Schnitzler , Max Ilgner , Otto Ambros , Friedrich Jähne , Christian Schneider , Carl Wurster , Carl Lautenschläger and Ernst Bürgin joined the NSDAP in the same year.

In contrast to the arrangements with the National Socialists are Carl Bosch's numerous, ultimately futile attempts to counter the National Socialist Jewish policy and stand up for individual Jewish citizens. These included in particular Bosch colleagues, chemists and employees of IG Farben, including Nobel Prize winner Fritz Haber, who lost all his functions in German science in 1933 and died in exile in 1934. Bosch saw the repression and dismissal of Jewish scientists as a major problem and criticized Nazi politics, which were hostile to science.

He repeatedly called for the promotion of science and education by the state and industry, whereby his international reputation protected him from political sanctions. He was of the opinion that politically important positions in industry, business and science must be filled with experts from these areas and not with Nazi politicians who are unfamiliar with the subject. With this he connected the hope of being able to prevent the worst. He realized too late that this hope was wrong and that he was complicit in the crimes of the Nazi regime. Bosch told Richard Willstätter about a meeting with Hitler where he discussed his Jewish policy. According to Bosch, he warned Hitler that the expulsion of Jewish scientists would set German physics and chemistry back a hundred years. Then Hitler began to scream: “Then we will work for a hundred years without physics and chemistry!” Then he rang for his adjutant and explained with exaggerated politeness that the privy councilor (Carl Bosch) wanted to leave. Both patterns of behavior - support of the Nazi regime when it came to economic matters, on the other hand, rejection in particular of Jewish policy when personally affected - characterize Bosch's ambivalent attitude.

Last years 1936 to 1940

In 1935, under pressure from the Nazi regime, Bosch gave up his chief position on the IG Farben board of directors to his confidante Hermann Schmitz. Bosch already knew Schmitz from the time of the Versailles negotiations and had brought Schmitz, then a board member of the metal bank, to BASF as CFO. Until his appointment as Bosch's successor, Schmitz had managed IG Farben's international business. Schmitz was considered a competent economist, Heinrich Brüning wanted to bring him into his cabinet as Minister of Economics. Bosch himself took over the chairmanship of the supervisory board as the successor to the late Carl Duisberg, with which he also held the office of chairman of the IG group.

In 1937 he took over the presidency of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society from Max Planck . On the occasion of the annual meeting of the committee of the Deutsches Museum in Munich, Bosch gave a speech on May 7, 1939, in which, according to the memoir of one of the participants, he said that “science can only flourish freely and without paternalism and that the economy and the state must inevitably perish if science is forced into such strangling political, ideological and racist restrictions as under National Socialism ” . As a result, Rudolf Hess asked Bosch to be relieved of all offices and forbid him to appear in public. Bosch then lost various posts, but remained President of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. After Bosch's death, Carl Krauch became chairman of the IG Farben supervisory board, a close associate of Bosch and previously on the executive board.

He repeatedly took on the role of a sponsor and donor. From 1930 onwards, through Imprimatur GmbH, he supported the liberal Frankfurter Zeitung with considerable financial means and enabled the establishment of a zoo in Heidelberg. He enjoyed doing handicrafts in his own workshop, as a locksmith, carpenter, lathe operator, precision mechanic or glass blower. Bosch was severely depressed, not least due to the loss of his boss's post and the political developments in Germany, as well as from excessive alcohol consumption at times, and attempted suicide in 1939 . Physical illnesses also made themselves increasingly noticeable, and in the winter of 1939/40 he went on a recreational trip to Sicily. He died a year later, on April 26, 1940, in Heidelberg. The family's grave is located in the Heidelberg Bergfriedhof in forest section B, high above the city on a pulpit, with an unobstructed view of the Rhine plain.

Honors and memberships

The Institution of Chemical Engineers voted Carl Bosch, together with Fritz Haber, to be the world's most influential chemical engineer of all time . Bosch received numerous awards, including an honorary doctorate from the Technical University of Karlsruhe in 1918 , the Liebig medal from the Society of German Chemists, together with the Bunsen medal from the German Bunsen Society for Physical Chemistry , the Siemens Ring, and the Grashof medal from the Association of German Engineers .

In 1931 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his contribution to the invention of high pressure chemical processes. It was the first time in the history of the Nobel Prize that the invention of a technical process had received an award. In his speech on Bosch's award, chemist Knut Vilhelm Palmær explained this by stating that technical processes often involve many people and that an award is therefore difficult. In the case of Bosch, however, this is different:

"This year, however, the Academy of Science believes it has discovered a technical advance of extraordinary importance and in respect of which it is also quite clear to which persons the principal merit is to ascribed."

"This year, however, the Academy of Sciences believes it has discovered a technical advance of extraordinary importance, in which it is also clear to whom the main earnings can be attributed."

He received the Wilhelm Exner Medal from the Wilhelm Exner Foundation of the Austrian Trade Association and the Carl Lueg Medal . Bosch was a member of various German and foreign scientific associations, such as the Kaiser Wilhelm Society , of which he became president in 1937. Alongside Ludwig Prandtl, Bosch was chairman of the Lilienthal Society founded in 1936 . He was a member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina , the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and the Prussian Academy of Sciences . In 1939 he was awarded the Goethe Prize by the city of Frankfurt .

The lunar crater Bosch and the main belt asteroid (7414) Bosch were named after Carl Bosch . The Carl-Bosch-Strasse at the BASF headquarters in Ludwigshafen am Rhein and the street of the same name and the Carl-Bosch-Haus in the Maxdorfer BASF-Siedlung, the Carl-Bosch-Haus in Frankfurt, among other things the headquarters of the Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker , the Carl-Bosch-Gymnasium in Ludwigshafen am Rhein, the Carl-Bosch-Schule in Heidelberg and Limburgerhof , a vocational school and the Carl-Bosch-Saal in the cCe Kulturhaus Leuna were also named after him.

In 1998 the Carl Bosch Museum Heidelberg opened on Schloss Wolfsbrunnenweg in Heidelberg . The former residence of Carl Bosch, the Villa Bosch, now houses the Klaus Tschira Foundation .

Bosch owned an extensive botanical collection, his herbarium , which he mainly gathered from purchase and barter deals. It comprises 17,000 documents. The collection came into the possession of the Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Frankfurt am Main in 1950 , where it has been processed and digitized ever since. The Bosch collection mainly includes deciduous mosses from Germany and Europe from the years 1817 to 1921, as well as liverworts and lichens , as well as a special collection of the moss genus Sphagnum .

Fonts (selection)

- The nitrogen in business and technology. In: Negotiations of the Society of German Natural Scientists and Doctors. 86/87, 1921, pp. 27-46.

- Socialization and chemical industry. In: The chemical industry. 28, 1921, pp. 44-62 (lecture at the general meeting of the Association of German Chemists, May 1921).

- Trade policy necessities. Association to protect the interests of the chemical industry. V., 1932.

- About the development of high pressure chemical technology in the construction of the new ammonia industry. Nobel Lecture given in Stockholm on May 21, 1932; also in: Chemische Fabrik. Volume 6, 1933, pp. 127-142.

- Problems of large-scale hydrogenation processes. Dybwad Publishing House, Oslo 1933.

- Problems of large-scale hydrogenation processes. In: The chemical factory. Volume 7, 1934, pp. 1-10.

literature

- Joseph Borkin : The unholy alliance of the IG colors. A community of interests in the Third Reich . Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-593-34251-0 .

- Günther Kerstein: Bosch, Carl . In: Charles Coulston Gillispie (Ed.): Dictionary of Scientific Biography . tape 2 : Hans Berger - Christoph Buys Ballot . Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1970, p. 323-324 .

- Karl Holdermann, Walter Greiling: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work . Econ, Düsseldorf 1953.

- Anonymous: Carl Bosch on his 60th birthday, a contribution to the history of large-scale chemical industry . In: Angewandte Chemie . tape 47 , no. 34 , 1934, pp. 593-594 , doi : 10.1002 / anie.19340473402 .

- Carl Krauch: Carl Bosch in memory . In: Angewandte Chemie . tape 53 , no. 27-28 , July 6, 1940, pp. 285-288 , doi : 10.1002 / anie.19400532702 .

- Richard Kuhn : Carl Bosch . In: The natural sciences . tape 28 , no. 31 , 1940, p. 481-483 , doi : 10.1007 / BF01482109 .

- Friedrich Klemm : Bosch, Carl. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 2, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1955, ISBN 3-428-00183-4 , p. 478 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Hans-Erhard Lessing : Bread for the World, Death to the Enemy. in: Stephan Leibfried et al. (Hg): Berlin's Wilde Energies - portraits from the history of the Leibniz Science Academy. de Gruyter, Berlin, 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-037598-5

- Alwin Mittasch : History of the ammonia synthesis . Verlag Chemie, Berlin-Weinheim 1951.

- Reiner F. Oelsner: Comments on the life and work of Carl Bosch. From industrial mechanic to head of the IG paint industry (= LTA research. H. 28). State Museum for Technology and Work, Mannheim 1998.

- Vaclav Smil : Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production . MIT University Press, Cambridge 2001, ISBN 0-262-19449-X .

- Ulrike Kohl: The presidents of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society under National Socialism: Max Planck, Carl Bosch and Albert Vögler between science and power (= Pallas Athene. Contributions to the history of universities and science. Volume 5). Steiner, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-515-08049-X (Zugl .: Berlin, Humboldt-Univ., Diss., 2001).

- Peter Hayes: Industry and Ideology: IG Farben in the Nazi Era. Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-78638-X .

Web links

- Literature by and about Carl Bosch in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Carl Bosch in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Ulrike Triebs, Lutz Walther: Carl Bosch. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1931 award to Carl Bosch

- Entry about Carl Bosch in the database of the Wilhelm Exner Medal Foundation .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hans-Erhard Lessing: Robert Bosch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2007, ISBN 978-3-499-50594-2 , p. 22.

- ^ Karl Holdermann: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work. Econ, Düsseldorf 1953, p. 21.

- ^ Max Planck Society: Carl Bosch 1937–1940. In: mpg.de. May 29, 1937. Retrieved November 10, 2018 .

- ^ Rudolf Jäckel, Marienhütte Kotzenau

- ^ Karl Holdermann: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work. Econ, Düsseldorf 1953, p. 91.

- ^ Albert Gieseler: Technical University of Berlin. Company history. In: albert-gieseler.de. Retrieved November 10, 2018 .

- ↑ biographical data, publications and Academic pedigree of Carl Bosch at academictree.org, accessed on 7 January 2018th

- ↑ Carl Krauch : Carl Bosch to the memory. In: Angewandte Chemie. Volume 53, 1940, p. 286, doi: 10.1002 / ange.19400532702 . Bosch commented on this on the occasion of the award of the Carl Lueg commemorative coin in 1935, In: Stahl und Eisen. Volume 55, 1935, p. 1506.

- ^ A b c d Karl Holdermann: Carl Bosch: 1874–1940; in memoriam. In: Chemical Reports. Volume 90 (1957), Issue 11, pp. 19-39.

- ^ Karl Holdermann: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work. Econ, Düsseldorf 1953, pp. 23-27.

- ↑ a b Alwin Mittasch: History of the ammonia synthesis. Verlag Chemie, Weinheim 1951, pp. 87-90.

- ↑ Hans-Erhard Lessing: Bread for the world, death to the enemy. in S. Leibfried (Hg): Berlins Wilde Energien de Gruyter, Berlin, 2015 p. 349

- ↑ Sir William Crookes: The Wheat Problem. Longmans, Green, and Co., London, New York, Bombay and Calcutta 1917.

- ^ Karl Holdermann: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work. Econ, Düsseldorf 1953, p. 50.

- ^ Karl Holdermann: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work. Econ, Düsseldorf 1953, pp. 51-61.

- ↑ Richard Abegg , Friedrich Auerbach : Handbook of inorganic chemistry. Volume 2, Hirzel, Leipzig 1908, p. 258. (full text)

- ↑ JDF Marsh, WBS Newling, J. Rich: The catalytic hydrolysis of hydrogen cyanide to ammonia. In: Journal of Applied Chemistry. 2, 1952, pp. 681-684, doi: 10.1002 / jctb.5010021202 .

- ^ Karl Holdermann: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work. Econ, Düsseldorf 1953, pp. 62-63.

- ↑ Bruno Waeser: The air nitrogen industry with consideration of the Chilean industry and the coke oven nitrogen . Springer-Verlag, 1932, ISBN 978-3-662-34599-3 , p. 135-136 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-662-34599-3 .

- ^ A b Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , pp. 180-181.

- ↑ Jürgen Hauschild, Sören Salomo: Innovation Management. 5th, revised, supplemented and updated edition. Vahlen, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8006-4353-0 , p. 98.

- ↑ a b Alwin Mittasch: History of the ammonia synthesis. Verlag Chemie, Weinheim 1951, pp. 90-115.

- ↑ Patent US1910599101 : Catalytic Agent for use in producing ammonia. Published on December 24, 1910 , inventors: Carl Bosch, Alwin Mittasch.

- ↑ Hans-Erhard Lessing: Bread for the world, death to the enemy. in S. Leibfried (Hg): Berlins Wilde Energien de Gruyter, Berlin, 2015 p. 357

- ↑ Carl Bosch: About the development of chemical high pressure technology in the construction of the new ammonia industry . Nobel Lecture given in Stockholm on May 21, 1932.

- ^ A b c Karl Holdermann: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work. Econ, Düsseldorf 1953, pp. 135-186.

- ^ Karl Holdermann: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work. Econ, Düsseldorf 1953, pp. 218-221.

- ↑ The flower miracle (video excerpt).

- ^ Niels Werber, Stefan Kaufmann, Lars Koch: First World War. Cultural studies manual . Verlag JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-476-02445-9 , p. 262.

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze: Fritz Haber 1868-1934: A biography. Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 285.

- ↑ Ulrike Kohl: The presidents of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in National Socialism: Max Planck, Carl Bosch and Albert Vögler between science and power. Steiner, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-515-08049-X , p. 114.

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser, Wolfgang von Hippel, Jeffrey Alan Johnson: The BASF. From 1865 to the present. History of a company. Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-49526-5 , pp. 179-181.

- ^ Karl Holdermann: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work. Econ, Düsseldorf 1953, pp. 146-186.

- ↑ Werner Abelshauser: The BASF. A company story. Verlag CH Beck, Munich, 2003, ISBN 3-406-49526-5 , pp. 181-182.

- ↑ Original text of the 1918 armistice in English on Wikisource .

- ↑ Joseph Borkin: The unholy alliance of the IG colors. A community of interests in the Third Reich. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-593-34251-0 , pp. 37-39.

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1918 was awarded to Fritz Haber "for the synthesis of ammonia from its elements.

- ↑ Tor E. Kristensen: A factual clarification and chemical-technical reassessment of the 1921 Oppau explosion disaster the unforeseen explosivity of porous ammonium sulfate nitrate fertilizer. Norwegian Defense Research Establishment / Forsvarets forskningsinstitutt, FFI-RAPPORT 16/01508, 2016.

- ^ Karl Holdermann: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work. Econ, Düsseldorf 1953, pp. 178-186.

- ↑ Franz Spausta: fuels for internal combustion engines. Springer Verlag, Vienna 1939, p. 54 (Reprint: ISBN 978-3-7091-5161-7 ).

- ↑ a b Joseph Borkin: The unholy alliance of the IG colors. A community of interests in the Third Reich. Campus, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1990, ISBN 3-593-34251-0 , p. 46.

- ↑ Joseph Borkin: The unholy alliance of the IG colors. A community of interests in the Third Reich. Campus, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1990, ISBN 3-593-34251-0 , p. 47.

- ↑ Joseph Borkin: The unholy alliance of the IG colors. A community of interests in the Third Reich. Campus, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1990, ISBN 3-593-34251-0 , p. 49.

- ^ A b Walther Jaenicke : 100 Years of the Bunsen Society 1894–1994. Verlag Steinkopff, Darmstadt 1994, ISBN 3-7985-0979-4 , pp. 87-88.

- ↑ Ulrike Kohl: The presidents of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in National Socialism: Max Planck, Carl Bosch and Albert Vögler between science and power. Steiner, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-515-08049-X , p. 116.

- ^ A b Peter Hayes: Carl Bosch and Carl Krauch: Chemistry and the Political Economy of Germany, 1925-1945. In: The Journal of Economic History. 47, 1987, pp. 353-363, doi: 10.1017 / S0022050700048117 .

- ↑ Otto Köhler : ... and today the whole world. The history of IG Farben and its fathers. Rasch and Röhrig, 1986, Papyrossa, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-89136-081-9 , p. 214.

- ↑ Carl Bosch: Where there's a will, there's a way. In: Information Service. Official correspondence of the German Labor Front. 25, 1933.

- ↑ Ernst Bäumler: Die Rotfabriker - family history of a global company (Hoechst) (= Piper. Volume 669). Piper, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-492-10669-2 , pp. 277 f.

- ↑ Thorsten Giersch: The group that made the World War possible for Hitler. In: Handelsblatt.com .

- ^ Yearbook of the Academy for German Law, 1st year, 1933/34. Edited by Hans Frank, Schweitzer Verlag, p. 252.

- ^ A b c Peter Hayes: Industry and Ideology: IG Farben in the Nazi Era . Cambridge University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-521-78638-X , pp. 91-92.

- ^ Karl Holdermann: Under the spell of chemistry: Carl Bosch - life and work. Econ, Düsseldorf 1953, p. 277.

- ↑ a b Ulrike Kohl: The Presidents of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in National Socialism. Max Planck, Carl Bosch and Albert Vögler between science and power. Steiner, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-515-08049-X , pp. 92-94.

- ↑ Joseph Borkin: The unholy alliance of the IG colors. A community of interests in the Third Reich. Campus, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1990, ISBN 3-593-34251-0 , p. 149.

- ↑ a b Joseph Borkin: The unholy alliance of the IG colors. A community of interests in the Third Reich. Campus, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1990, ISBN 3-593-34251-0 , p. 72.

- ↑ a b Reiner F. Oelsner: Comments on the life and work of Carl Bosch. From industrial mechanic to head of the IG paint industry (= LTA research. H. 28). State Museum for Technology and Work, Mannheim 1998, p. 37.

- ^ Karl Holdermann: Carl Bosch: 1874–1940; in memoriam. In: Chemical Reports. Volume 90 (1957), Issue 11, pp. 272-273.

- ↑ Joseph Borkin: The unholy alliance of the IG colors. A community of interests in the Third Reich. Campus, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1990, ISBN 3-593-34251-0 , p. 58.

- ↑ Guido Knopp: The chemists of death. In: Back then. 7/1998, p. 9.

- ↑ David Nachmansohn: German-Jewish Pioneers in Science 1900-1933. Springer Verlag, 1979, ISBN 1-4612-9972-1 , p. 175.

- ↑ Hans-Erhard Lessing: Robert Bosch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2007, ISBN 978-3-499-50594-2 , p. 142.

- ↑ Joseph Borkin: The unholy alliance of the IG colors. A community of interests in the Third Reich. Campus, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1990, ISBN 3-593-34251-0 , p. 148.

- ↑ Franz-Josef Baumgärtner: I was there! A reminder of the C. Bosch speech of 1939. In: deutsches-museum.de , accessed on December 8, 2018 (PDF).

- ↑ Ulrike Kohl: The presidents of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in National Socialism: Max Planck, Carl Bosch and Albert Vögler between science and power. Steiner, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-515-08049-X , pp. 162-163.

- ^ Richard Kuhn : Carl Bosch. In: Natural Science. 1940, p. 482.

- ↑ Ulrike Kohl: The presidents of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in National Socialism: Max Planck, Carl Bosch and Albert Vögler between science and power. Steiner, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-515-08049-X , p. 120 and p. 123.

- ^ Hans R. Kricheldorf: People and their materials. From the Stone Age to today (= science experience ). Verlag Wiley-VCH, Weinheim 2012, ISBN 978-3-527-33082-9 , p. 112, urn : nbn: de: 101: 1-2014081611554 .

- ^ Haber and Bosch named top chemical engineers. (No longer available online.) In: icheme.org. February 21, 2011, archived from the original on July 19, 2011 ; accessed on November 10, 2018 .

- ^ A b c d Member entry of Carl Bosch at the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina , accessed on April 11, 2015.

- ^ Vaclav Smil: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production. MIT University Press, Cambridge 2000, ISBN 0-262-19449-X , p. 85.

- ↑ Katharina Trittel: Hermann Rein and the aviation medicine. Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh, 2018, ISBN 978-3-506-79219-8 , pp. 198–199.

- ^ Bosch in the Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature of the IAU (WGPSN) / USGS .

- ↑ The Carl Bosch Moos Collection is being digitized with funds from the Klaus Tschira Foundation.

- ^ Jan-Peter Frahm , Jens Eggers: Lexicon of German-speaking bryologists . Self-published, Norderstedt 2001, ISBN 3-8311-0986-9 .

- Remarks

-

↑ The caption reads:

“The wreckage, September 21, by explosions, followed by fire, of the great dye works at Oppau near Ludwigshafen in the Rhine, where several hundred persons were killed and thousands injured, was the greatest disaster of its kind that has ever occurred in Germany , and probably in the world. The entire plant was destroyed, as well as the greater part of the surrounding town. The first explosion occurred at the huge gas holders, and the above picture shows the resulting wreckage in their immediate vicinity. Seismographs at the Stuttgart Observatory, some 83 miles away, registered the shock of the first explosion after 7:30 am and a second, more violent one, 22 seconds later. Damage to buildings were reported within a radius of over 50 miles from Oppau. "

“The destruction of the large inking plants in Oppau near Ludwigshafen am Rhein on September 21st by explosions, followed by fires in which several hundred people were killed and thousands injured, was the greatest disaster of its kind ever in Germany and probably in the World has happened. The entire complex was destroyed, as was most of the surrounding city. The first explosion occurred near the huge gas containers, and the picture above shows the devastation in close proximity. Seismographs at the Stuttgart Observatory, about 83 miles away, registered the shock wave of the first explosion around 7:30 a.m. and a second, more violent one, 22 seconds later. Building damage was reported within 50 miles of Oppau. "

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bosch, Carl |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German chemist and Nobel Prize winner |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 27, 1874 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cologne |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 26, 1940 |

| Place of death | Heidelberg |