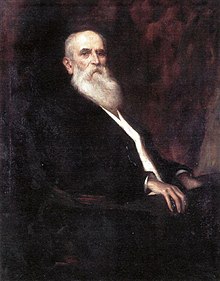

Friedrich Engelhorn

Friedrich Engelhorn (born July 17, 1821 in Mannheim ; † March 11, 1902 there ) was a German entrepreneur. In 1865 Engelhorn founded Badische Anilin- & Soda-Fabrik AG ( BASF ) in Mannheim , whose factory premises were located in Ludwigshafen am Rhein in the Palatinate on the other side of the Rhine .

youth

Friedrich Engelhorn was born on July 17, 1821 in Mannheim, where his father Johann Engelhorn ran the Gasthaus Stadt Augsburg on the Planken . His eldest brother Jean later became the founder of J. Engelhorn Verlag in Stuttgart . From 1830 Friedrich Engelhorn attended the Mannheim Lyceum . After four school years he left school and then completed a three-year training as a goldsmith. Then he went on a journey that took him to Mainz, Frankfurt, Munich, Vienna, Geneva, Lyon and Paris.

Goldsmith

On November 14, 1846 Friedrich Engelhorn put in Mannheim Master exam as a goldsmith and was admitted to the local goldsmiths' guild in March of the following year. At first he pursued the trade in his parents' house. He specialized in the manufacture of jewelry and was referred to in contemporary documents as a "jewelry maker " and "jeweler". Soon after opening his shop, Engelhorn employed several people. Finally, he acquired house C 4, 6 in Mannheim's city squares , which he moved into in the summer of 1848.

In the 1848 revolution

In the years 1848 and 1849 Friedrich Engelhorn was politically active in a variety of ways during the Baden Revolution . As a voter, he took part in the election of the Mannheim MP for the National Assembly, which met for the first time in May 1848 in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt. From autumn 1848 Friedrich Engelhorn was active as an officer in the Mannheim vigilante group.

When the Prussian Army threatened to include the city of Mannheim during its campaign against the revolutionary uprising in the Grand Duchy of Baden , Friedrich Engelhorn was finally given the command of the vigilante in June 1849. Through resolute personal efforts, he succeeded in securing a peaceful surrender of the city and preventing the unnecessary destruction of Mannheim. With the help of dragoons who defected to the counter-revolution, Engelhorn secured the 80,000 guilders' treasury of the government of the Lower Rhine District, with which the revolutionaries wanted to flee. At Engelhorn's instructions, strategically important points in the city were immediately occupied. With a clever ruse he succeeded in playing the revolutionaries' cannons into the hands of the counter-revolutionaries. The fact that the Prussians were able to occupy the city a few hours later without a fight was largely thanks to Engelhorn. His courageous demeanor was recorded in a report in the Mannheim city council minutes, which states that "Colonel Engelhorn [...], according to the testimony of all [...] on that day, behaved with great energy" and through his commitment "a bloody [ n] catastrophe ”could be prevented.

As a gas entrepreneur

As Engelhorn's goldsmith's workshop ran into difficulties as a result of the economic crisis triggered by the revolution, he looked for another field of activity in the summer of 1848. He founded a gas works with two partners, which started production in late 1848. Due to his experience as a gas manufacturer, he was entrusted with the construction of the municipal gasworks in 1851 together with Friedrich Sonntag from Mainz and Nepomuk Spreng from Karlsruhe. After its commissioning in December of the same year, Friedrich Engelhorn took over the commercial management of the plant.

Coal tar , an annoying waste product , was created during the production of the luminous gas . Engelhorn heard of the possibility of producing dyes from coal tar distillates, because the Englishman William Henry Perkin (1838–1907) was the first to succeed in 1856 in synthesizing aniline violet ( mauvein ) from German coal tar distillates . Justus von Liebig had also pointed out that this coal tar could be used to produce red dye or indigo .

Engelhorn founded a factory and secured the collaboration of the chemist Carl Clemm , who had studied with Justus von Liebig. Together with Carl Clemm, his long-term partner Nepomuk Spreng and the Mannheim businessman Otto Dyckerhoff, he founded the aniline paint factory Dyckerhoff, Clemm und Comp. The share capital of the general partnership was 100,000 guilders. A year earlier, in July 1860, Engelhorn had already acquired a former iron and steel works in the Jungbusch district of Mannheim , which served as a production facility. He sold his new dyes worldwide, on the European mainland this was taken over by the trading house Knosp in Stuttgart.

Two years later Dyckerhoff left the company and August Clemm joined the company in his place . The company name was changed to Sonntag, Engelhorn and Clemm .

Foundation of BASF

For the production of the aniline dyes, the Sonntag, Engelhorn and Clemm company needed various acids, which they obtained from the chemical factories association in Mannheim . Engelhorn realized that profits could be increased significantly if the entire manufacturing process from raw material to end product was in one hand. Therefore, he sought a collaboration with the chemical factories association. In the spring of 1864 a merger agreement was signed between the two companies. However, the association's shareholders rejected the offer.

After the collaboration with the Chemical Factory Association had failed, Engelhorn decided to produce the raw materials on its own. Together with eight partners, he founded the Badische Anilin- & Soda-Fabrik (BASF) in April 1865 . Friedrich Engelhorn, the two chemists Carl and August Clemm and the technician Julius Giese were appointed to the company's board of directors. Engelhorn was also active on the company's board of directors.

Since the previous site was now too small, Engelhorn wanted to acquire a plot of land on the left bank of the Neckar, south of today's Ebertbrücke , which was near the Mannheim Tattersall . On behalf of BASF, the WH Ladenburg & Söhne bank negotiated the sale of 40 acres of land with the city of Mannheim. The city council agreed, but the citizens' committee had the last word . Now the chemical factories association showed interest in the area and made an offer several thousand guilders higher. At the meeting of the citizens' committee on April 12th, numerous members pleaded for the site to be auctioned publicly in order to achieve the best possible price. After the discussion, the decision was made: 42 votes were in favor of the sale of the site to BASF, 68 against. On the afternoon of April 12, 1865, Friedrich Engelhorn, together with Seligmann and Carl Ladenburg, crossed the ship's bridge to the farmers on the Hemshof and in Friesenheim in order to purchase the necessary land there. No interested party appeared at the public auction of the Mannheim site, which the city of Mannheim held fourteen days after the citizens' committee voted.

Friedrich Engelhorn quickly set about building the factory. Immediately after receiving the concession, the groundbreaking ceremony took place in May 1865. The first parts of the plant went into operation in autumn of the same year. After the construction work was completed, a technical commission approved the facilities in June 1867.

As director of BASF

As the commercial director of BASF, Friedrich Engelhorn played a key role in its rapid rise. Two years after the company was founded, the plant already employed 315 people. With Heinrich Caro , Heinrich Brunck and Carl Glaser , other young chemists joined the company.

The company was also active in the field of research. In 1868 it was possible for the first time to synthetically produce the red dye alizarin . Engelhorn secured the collaboration of the two explorers Carl Graebe and Carl Liebermann . When synthetic production began in industrial style in 1870, it was the first great success for BASF. The English chemist William Henry Perkin had also developed a process for producing alizarin on a large scale independently of BASF . To avoid a protracted patent dispute, Engelhorn proposed to the Englishman that the world market should be divided. This agreed and finally a contract was concluded on March 13, 1870 in London.

Initially, BASF had its products sold through established paint dealers. However, the success of the Alizarin made it necessary to set up an own sales organization. Engelhorn made contacts with the Stuttgart paint companies of Gustav Siegle and Rudolf Knosp and finally, in 1873, the three factories merged.

As commercial director, Engelhorn was also responsible for the social concerns of the workers. Under his aegis, the first BASF workers' settlement was built on the Hemshof in 1871 and comprised 50 residential buildings. The model of a settlement house was exhibited at the "Third Palatinate Industrial Exhibition" in Kaiserslautern, where it received the attention and recognition of the German Empress Augusta in August 1872 . A few weeks later, Friedrich Engelhorn was awarded the Knight's Cross 1st Class of the Bavarian Order of Merit of St. Michael .

In 1880 Adolf Baeyer succeeded in synthesizing the blue dye indigo , which was considered the “king of natural dyes”, in the laboratory. To secure the development, BASF immediately signed a contract with the chemist. But it took almost two decades before an inexpensive process was developed and the industrial production of indigo could begin.

Further shareholdings of Friedrich Engelhorn

Friedrich Engelhorn's entrepreneurial activity was not limited to BASF. From 1865 he was involved in the later Mannheim rubber, gutta-percha and asbestos factory . In his native Mannheim, he also became a partner in a bread factory. He was a co-founder of Rheinische Creditbank , Mannheimer Versicherung and Mannheimer Rückversicherung, and then took on responsibility for future development on the company's supervisory boards. Engelhorn also sat on the supervisory boards of the Badische Gesellschaft für Zuckerfabrikation , the Palatinate Ludwig Railway , the Mannheim Portland Cement Factory and the Rheinische Hypothekenbank .

Engelhorn's financial commitment also went beyond the borders of the "Rhine-Neckar area". He became a partner in the Durlach steam brickworks , the consolidated alkali works in Westeregeln , the Neustaßfurt potash mine , the Deutsche Celluloid-Fabrik AG in Eilenburg, Saxony, and the Kannengießer brothers in Ruhrort , from which the mining and shipping corporation emerged in 1895 . He was also the owner of the Konstanz patent interlocking tile company Fr. Engelhorn . In 1897 he bought the Perutz photo works from Otto Perutz .

In Mannheim, Friedrich Engelhorn was also involved in the creation of new building areas. In 1883 he played a major role in the development of the so-called "tree nursery gardens". Engelhorn acquired the future building land and developed it with roads and sewer pipes that were built at his own expense. He then sold the plots to architects and contractors. A few years later he proceeded in a similar way in the Lindenhof district , where he acquired the so-called Gontardsche Gut in 1891 .

Acquisition of the company "C. F Boehringer and Sons "

After disagreements with his partners, Friedrich Engelhorn resigned from the BASF Board of Management in 1883. In the same year he invested large amounts in the Mannheim-based pharmaceutical company CF Boehringer and Sons . At the same time, his eldest son Friedrich joined the management team, who made the company one of the leading quinine manufacturers in the world in the following years.

In recognition of his services to the economic development of the city of Ludwigshafen, Friedrich Engelhorn was appointed to the council of commerce by the Bavarian government when he left BASF .

Private life

Friedrich Engelhorn was married to the Mannheim brewer's daughter Marie Brüstling (1825–1902) since June 1847. The marriage had twelve children. The eldest son died in childhood.

The three sons had different careers. Friedrich (1855–1911) completed his chemistry studies at the Kaiser Wilhelm University of Strasbourg with a doctorate and then took over the management of CF Boehringer and Sons in Mannheim. Robert (1856–1944) made a name for himself as a genre and landscape painter and played a key role in founding the art gallery in Baden-Baden. Louis (1859–1930) emigrated to America and worked as a managing director in various companies in New York.

Of the eight daughters, Elise (1852–1920) emerged, who took on entrepreneurial responsibility herself. In 1872 she married the ironworks and landowner Eugen von Gienanth from Eisenberg. After his early death in 1893, she headed the Eisenberg ironworks for 18 years.

At the beginning of the 1870s, Friedrich Engelhorn decided to have a representative residence built for himself and his family in Mannheim. He acquired a baroque aristocratic palace in the Breite Straße not far from the Mannheim Palace, in the place of which the Palais Engelhorn was built in the Renaissance style in the years 1873–1875. The interior design was done by the Stuttgart architect Adolf Gnauth . In the years 1883–85 the town house was expanded by Wilhelm Manchot . The centerpiece of the extension was a “Moorish Hall” designed with elements of Islamic architecture .

Death and afterlife

Friedrich Engelhorn died on March 11, 1902. He found his final resting place in Mannheim's main cemetery . Five years before his death, on the occasion of his golden wedding anniversary, he and his wife founded the “Friedrich and Marie Engelhorn Foundation”, which supported families in need in Mannheim.

Friedrich Engelhorn's name lives on in various ways to this day. In Mannheim, in Maxdorf near Ludwigshafen and in Eilenburg in Saxony , streets were named after the chemical entrepreneur. In 1957, BASF named its new administration building, which was the tallest building in Germany when it was built, the Friedrich-Engelhorn-Hochhaus . Due to severe structural damage and defects, the building had to be demolished in 2013/14. A new building is not planned. The memory of Friedrich Engelhorn is also preserved by the Friedrich Engelhorn Archive eV in Mannheim.

literature

in alphabetical order by authors / editors

- Wolfgang von Hippel: On the way to becoming a global company . In: Werner Abelshauser (ed.): The BASF - A company history . Munich 2002, pp. 19–116.

- Gustaf Jacob: Friedrich Engelhorn - The founder of the Badische Anilin- & Sodafabrik (= writings of the Society of Friends of Mannheim . Volume 8). Mannheim 1959.

- Albert Krieger : Friedrich Engelhorn . In: ders., Karl Obser (Ed.): Badische Biographien 6. Winter, Heidelberg 1935, p. 162 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Adolf Leber: Engelhorn, Friedrich. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3-428-00185-0 , p. 514 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Sebastian Parzer: Friedrich Engelhorn as founding director of the "Badische Anilin- & Soda-Fabrik". In: Yearbook of the Hambach Society 2015. 22nd year, pp. 89–115.

- Sebastian Parzer: The early years of Friedrich Engelhorn (1821–1864) - student, goldsmith, commander of the vigilante group and gas manufacturer. Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft , Worms 2012, ISBN 978-3-88462-319-0 .

- Sebastian Parzer: Friedrich Engelhorn: BASF founder - entrepreneur - investor (1865–1902). Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 2014. ISBN 978-3-88462-352-7 .

- Hans Schröter: Friedrich Engelhorn - An entrepreneur portrait of the 19th century. Landau 1991.

Web links

- Literature by and about Friedrich Engelhorn in the catalog of the German National Library

- Friedrich Engelhorn Archive eV

- Illustrated genealogical website for Friedrich Engelhorn and his family

Individual evidence

- ^ April 6, 1865: Friedrich Engelhorn: BASF - Baden factory in the Palatinate | The timeline | History of the Southwest. June 23, 2015, accessed March 29, 2020 .

- ^ Sebastian Parzer: The early years of Friedrich Engelhorn (1821–1864) - pupil, goldsmith, commander of the vigilante group and gas manufacturer. Worms 2012, p. 10 f.

- ↑ Sebastian Parzer: The early years. P. 14 f., P. 21.

- ↑ Sebastian Parzer: The early years. P. 24, p. 26.

- ↑ Sebastian Parzer: The early years. P. 32 f.

- ↑ Sebastian Parzer: The early years. Pp. 60-65.

- ^ Heinrich von Feder: History of the city of Mannheim. Volume 22. Mannheim / Strasbourg 1877, p. 356.

- ^ Parzer: The early years. Pp. 35-38.

- ^ Parzer: The early years. Pp. 66-70.

- ^ Parzer: The early years. P. 82, p. 86.

- ^ Parzer: The early years. P. 88.

- ↑ Wolfgang von Hippel: On the way to becoming a global company. In: Werner Abelshauser (ed.): The BASF - A company history. Munich 2002, p. 29 f.

- ↑ Hippel, p. 29.

- ↑ Hans Schröter: Friedrich Engelhorn - An entrepreneur portrait of the 19th century. Landau 1991, p. 125.

- ↑ Hippel, p. 36, p. 39.

- ↑ Hippel, p. 38.

- ↑ Hippel, p. 42 f.

- ^ Parzer: Friedrich Engelhorn: BASF founder - entrepreneur - investor (1865-1902). Worms 2014, p. 29.

- ↑ Central Committee of the III. Palatinate. Industry exhibition: report on the III. Palatine industrial exhibition in Kaiserslautern in the summer of 1872. Kaiserslautern 1873, p. 150 f. and p. 202.

- ^ Parzer: BASF founder. P. 62.

- ^ Parzer: BASF founder. Pp. 39-58.

- ^ Parzer: BASF founder. Pp. 58-60, pp. 71-79.

- ↑ Schröter, p. 208 f.

- ^ Parzer: BASF founder. P. 110.

- ^ Parzer: The early years. P. 26, p. 90.

- ↑ Alexander Kipnis: Art .: Engelhorn, Johann Friedrich August. In: Baden biography. NF 5 (2005), p. 66 f.

- ↑ Ursula Blanchebarbe: Kunsthalle Baden-Baden - exhibitions, productions, installations 1909-1986. Baden-Baden 1986, pp. 10-12, p. 21.

- ^ Parzer: BASF founder. Worms 2014, p. 115.

- ↑ Ulrich Freiherr von Gienanth: 250 years Eisenberg Eisenberg - The history of the Gienanth family of iron foundries. Eisenberg 1986, p. 32, p. 47.

- ↑ Tobias Möllmer: The Palais Engelhorn in Mannheim. History and architecture of a Wilhelminian town house. Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 2010, ISBN 978-3-88462-297-1 , p. 114.

- ↑ Möllmer, p. 134, p. 138.

- ^ Wolfgang Münkel: The cemeteries in Mannheim. Mannheim 1992, p. 118.

- ^ Parzer: BASF founder. P. 109f.

- ↑ MARCHIVUM: street names, Friedrich Engelhorn road. Retrieved August 27, 2018 .

- ^ Parzer: BASF founder. P. 131.

- ^ Parzer: BASF founder. P. 132f.

- ^ The Rhine Palatinate - Rebekka Sambale: No BASF high-rise. Retrieved February 29, 2020 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Engelhorn, Friedrich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German entrepreneur |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 17, 1821 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mannheim |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 11, 1902 |

| Place of death | Mannheim |