Palatine Ludwig Railway

The Palatinate Ludwig Railway (also known as the coal railway or Bexbach Railway) is a 106.6 kilometer long historical railway line within the then Bavarian Palatinate , which ran from Ludwigshafen am Rhein to Bexbach . It was created between 1847 and 1849.

It got its name from the operator, the Palatinate Ludwig Railway Company . The line was the first east-west connection through the Palatinate. From 1850 to 1852 it was extended to Neunkirchen , Sulzbach and Saarbrücken in what was then the Prussian coal mining area . It no longer exists as an operational unit. The Ludwigshafen - Homburg section later merged with the Mannheim - Saarbrücken railway , which has existed since 1904 and 1969, respectively. For this reason, the term Palatine Ludwig Railway or Ludwig Railway is now imprecise for them. The Homburg - Bexbach section is now part of the Homburg - Neunkirchen railway line .

Emergence

prehistory

From 1816, the territory called the Rhine District belonged to the Kingdom of Bavaria as part of the Treaty of Munich . In it it formed an exclave . After the Stockton and Darlington Railway became the world's first railway in the course of industrialization in the United Kingdom in 1825 and the Ludwig Railway between Nuremberg and Fürth in 1835 , plans arose to set up a railway line within the Rhine district. Initially, the plan was to put a north-south railway line into operation, which would compete with the Mannheim – Basel line planned by Baden .

At the same time, efforts were made to build a main line in an east-west direction. Entrepreneurs from the Prussian Saar district decided on January 26, 1836 in Saarbrücken to found a company for the construction of a railway from Saarbrücken to Mannheim. Since it was clear that it would mainly run through the Rhine district, Bavaria was against having the activities controlled from the Prussian Saarbrücken.

Meanwhile the Sulzbacher glass manufacturers and brothers Carl Philipp and Johann Ludwig Vopelius brought a connection from Saarbrücken to Strasbourg into play. France relied on a stretch on the left bank of the Rhine from Strasbourg to the Rheinschanze . The realization of both lines - especially the former - would have had the effect of isolating the Rhine district in terms of traffic. The planned route on the left bank of the Rhine also harbored the risk of granting France a strategic advantage in the event of war , as its troops could easily reach Mainz in this way. At the same time, industrialists from the Rhine district were interested in making it easier for the mines in the Bexbach catchment area to transport the coal to the Rhine.

On December 21, 1837, the Bavarian King Ludwig I approved both the construction of a main line in an east-west direction from the Rheinschanze to the Prussian border near Bexbach to connect to the planned Prussian route from Saarbrücken to Bexbach and the establishment of a route on the left bank of the Rhine in North-south direction from the Rheinschanze to the French border near Lauterbourg with a connection to the planned French route from Strasbourg to Lauterbourg. He also stipulated that the two directorates had to be located within the Palatinate and that only Bavarian shareholders were allowed to belong to the two stock corporations. This eliminated the influence of the Saarbrücken Committee on the route within Bavaria. The two joint-stock companies to be founded should be privileged for a certain period of time, a maximum of 99 years; then ownership of the two railways had to pass to the Bavarian state. The share subscription for the east-west highway took place from January 1, 1838, while the date for the share subscription for the unrealized north-south highway should follow later.

On January 10, 1838, a provisional company was formed, which wanted to drive a main line in an east-west direction. This should mainly serve to transport coal from the Saar area to the Rhine. Bavaria was not interested in a state-owned railway company within its area on the left bank of the Rhine.

The main reason for the choice of location was that hard coal was mined in the Frankenholz pit (now part of Bexbach). Frankenholz was the only coal mine in the Kingdom of Bavaria in which hard coal was found; In the other Bavarian coal mines, only the so-called pitch coal , which has a significantly lower calorific value, was extracted. Hard coal was the more efficient fuel for steam locomotives in particular.

In addition to the necessary construction of the railway line to Ludwigshafen, there was another problem when transporting the coal mined in Frankenholz: Frankenholz is about 200 meters above the level of the Bexbach train station. The transport problem was solved by building a cable car about 6 km between Bexbach and Frankenholz, with which the extracted raw coal was transported to the Bexbach train station. Before being loaded onto the train, the coal was separated from the slag in what is known as coal washing . The slag was piled up in Bexbach and today forms the now wooded heap with the miner's monument St. Barbara.

From Ludwigshafen the hard coal was transported up the Main river in the direction of Bavaria. This was mainly done by the state-sponsored Bavarian-Palatinate Steam-Schlepp-Schifffahrts-Gesellschaft .

planning

Several route variants have been worked out in the western section of the route. Establishing the Bavarian St. Ingbert as the western end point was dropped under pressure from Prussia, as the Prussian state wanted to extend the long-term connection to Saarbrücken as far as possible over its own territory. The city of Neunkirchen and its numerous coal deposits were also wanted. Therefore, Bexbach was chosen as the end point of the route, from where the extension via Neunkirchen and the Sulzbachtal was to take place later.

After Bexbach had been determined as the end point, it was initially planned to run the route directly to Kaiserslautern . Zweibrücken pleaded for a route further south via its urban area, which, however, would have meant too long a detour, so that as a compromise Homburg should finally be connected.

To the east of Kaiserslautern the complicated overcoming of the Palatinate Forest had to be accomplished. Two routes were discussed in the topographically difficult terrain. At first the responsible engineers thought of a route through the Dürkheimer Tal . However, this route would have required large viaducts over or wide loops into these valleys because of its deeply cut side valleys. In addition, the Frankensteiner Steige had such a steep gradient that stationary steam engines and rope hoists would have been necessary to overcome the difference in altitude. For this reason, a variant over the Neustadter Tal was chosen , which, according to an expert opinion, would also be difficult to overcome, but is feasible and, in contrast to the Dürkheimer Tal, would not require ramps with rope hoists.

There were also different ideas about the eastern end of the route. Speyer , the capital of the Palatinate, advocated becoming the end point of the route instead of the Rheinschanze itself. The main argument was that the cathedral city was an old trading center, while the Rheinschanze, as a mere military base, would be nothing more than a transshipment point for the onward transport of goods. These efforts did not prevail, however, because the right bank of the up-and-coming Rhine-Neckar region - especially Mannheim - was the preferred sales market and the export of coal to the area beyond the Rhine was considered more important. However, Speyer was to get a branch line.

Foundation of the railway company and start of construction

The Bavarian Railway Company of the Palatinate / Rheinschanz-Bexbacher-Bahn, the later Palatinate Ludwigsbahn-Gesellschaft , founded on March 30, 1838 , planned a railway line between the Rheinschanze (today Ludwigshafen am Rhein ) opposite Mannheim and the western border with Prussia near Bexbach. Several years of discussion between the various interest groups passed. The actual construction phase began in April 1844 with the appointment of the engineer Paul Camille Denis , who was responsible for the Nuremberg – Fürth line, which opened in 1835 as the first German railway line , to the company's board of directors.

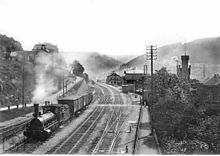

The construction of the line began at the same time in Ludwigshafen , Neustadt an der Haardt , Kaiserslautern and Homburg in the direction of Bexbach . Between the border with Prussia and Kaiserslautern, the builders had to raise ten meters of earth as a railway embankment due to the boggy soil in the Landstuhler Bruch . From April 1846, rails were laid between Ludwigshafen and Neustadt.

Originally it was planned to build train stations only in Ludwigshafen, Schifferstadt, Haßloch, Neustadt, Lambrecht-Grevenhausen, Frankenstein, Kaiserslautern, Landstuhl, Bruchmühlbach , Homburg and Bexbach. However, it was subsequently agreed to provide Hochspeyer, Böhl and Mutterstadt with stations as well.

Further development

Gradual opening

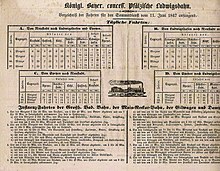

The Ludwigshafen – Neustadt section was opened on June 11, 1847. The opening train running from Ludwigshafen to Neustadt was hauled by the Haardt locomotive , which had road number 1. The crossing of the Palatinate Forest between Kaiserslautern and Neustadt turned out to be particularly laborious , which is why the railway was not continuously expanded to the west. In the Homburg – Kaiserslautern section, the substructure was already in place at this point, while the earth dams had only been completed by Frankenstein.

The Homburg – Kaiserslautern section was released on July 2, after trains carrying a total of 5,584 passengers had already used it on a trial basis from June 10 to 15. On December 2nd of that year, the section to Frankenstein was tied through. On June 6 of the following year, the western section to Bexbach was completed. A direct connection to the local coal mines was not made in view of the planned connection to Neunkirchen and Saarbrücken. In particular, the completion of the Neustadt – Frankenstein section was delayed due to the land acquisition required for the railway construction and also due to the difficult topography. In this way, ten tunnels were created due to the hills and foothills of various mountains.

At the same time, the German Revolution delayed the construction of the line. In addition, the actors used the existing sections for their own purposes. Irregulars destroyed part of the tracks near Mutterstadt and Haßloch in order to prevent Prussian soldiers from using the Ludwigsbahn to Neustadt. In addition, they transported the removed rails to Neustadt to make repairs more difficult. The Homburg Freikorps occupied Bexbach station. On June 13, 1849, its members fled in a train that they had assembled and were chasing the Uhlans . During this time, the personnel stationed at the stations were forced to compromise with the revolutionaries in order to be able to continue the railway operations.

The permanent opening finally took place on August 25, 1849. Before that, carriages - then known as omnibuses - had taken over the traffic between the two sections of the route.

Follow-up time

Already on October 20, 1850, the connection to the Prussian coal and steel location Neunkirchen followed , after a coal train had already driven east from the Heinitz mine on September 7th . In 1851, under the direction of William Fardely, a telegraph line was created along the Neunkirchen – Ludwigshafen route. From November 16, 1852, continuous traffic to Saarbrücken was possible. A short time later, the Ludwig Railway Company introduced mail transport by rail between Ludwigshafen and Bexbach. With the completion of the routes from Mainz to Ludwigshafen and Neunkirchen to Saarbrücken, there was a connection between Mainz and Paris from 1853. The extensive traffic required the construction of a second track, the substructure of which already existed. As early as July 1856, the Ludwig Railway, including its continuation to Neunkirchen, was consistently double-tracked. Two years later, another train station, Bruchmühlbach, was built between Hauptstuhl and Homburg. From 1858 to 1860 Prussia built the so-called Rhein-Nahe-Bahn in stages from Bingerbrück to Neunkirchen, which competed with the Ludwigsbahn.

For the Alsenz Valley Railway, which branches off between Frankenstein and Hochspeyer and opened in full length in 1871 , Hochspeyer received a new branch station . From then on, its predecessor was used exclusively for freight transport. In the period that followed , further train stations and stops followed along the Ludwig Railway with Mundenheim , Rheingönheim , Einsiedlerhof , Kindsbach and Eichelscheid - Lambsborn . With the opening of the St. Ingbert – Saarbrücken railway in 1879, there was a further railway connection on the Homburg – Saarbrücken route in combination with the Homburg – Zweibrücken railway that opened in 1857 and the Würzbach Railway, which was opened in full in 1867 . This was shorter than the previous route via Bexbach and Neunkirchen. Trains to Saarbrücken preferred these to the route via Bexbach from now on.

Coal trains from the direction of Bexbach, which drove eastwards via the Zweibrücken – Landau main line, opened in 1875 , had to “turn heads” at Homburg station . To solve this problem, the previous turn of the track west of Homburg in the direction of Bexbach was abandoned and the route was changed so that a connecting curve to the route to Zweibrücken was possible. The renovation work began in the spring of 1880. The opening followed on October 15, 1881. In 1900, a freight railway running parallel to the existing line was built from Schifferstadt to Oggersheim station on the line to Mainz, which was used to bypass Ludwigshafen.

Development after 1904

From January 1, 1904, for strategic reasons, there was a direct connection from Homburg to Rohrbach via Limbach and Kirkel, which was initially intended to be a continuation of the Glantalbahn that followed four months later . In this way, the shortest possible route was created between Homburg and Saarbrücken. As a result, the previous Ludwig Railway no longer formed an operational unit. Between Homburg and Bexbach, new kilometers were built accordingly. The zero point was originally on the Prussian-Bavarian border between Bexbach and Neunkirchen and is now in Homburg; the kilometers are there in the opposite direction to Neunkirchen. Only from Homburg to Ludwigshafen did the old kilometers remain. On January 1, 1909, the former Ludwig Railway, along with the other railway lines within the Palatinate, became the property of the Bavarian State Railways .

The Einsiedlerhof marshalling yard , which was built in 1920 and replaced the one in Kaiserslautern, brought about a radical change in the route of the former Ludwig Railway. Because of the limited space in the Kaiserslautern - Einsiedlerhof section, it was necessary to relocate the two tracks to the north. After the Second World War, the former line was gradually electrified from 1961 to 1966. At the same time, the Deutsche Bundesbahn began to move the Ludwigshafen main station to a new location . In 1969 this measure was completed. The previous terminus and its tracks were demolished.

The Ludwigshafen - Homburg section is currently under the VzG route number 3280 after the Ludwigshafen main station has been rebuilt and short sections to speed up as part of the Mannheim - Saarbrücken railway . The connection via Bexbach is now part of the Homburg - Neunkirchen railway line (VzG number 3282).

traffic

passenger traffic

Traffic up to the founding of the Palatinate Railways

The first timetable for the Ludwigshafen – Neustadt section, which was opened in 1847, initially had four pairs of trains. The trains with those who served Speyer were winged or united in Schifferstadt. After the Kaiserslautern – Homburg section was opened in 1848, a total of three pairs of trains initially ran there and five in the Ludwigshafen – Neustadt section. On October 1, the number of train pairs in the east was reduced to four again. From December the trains in the west connected to Frankenstein. At the same time, another pair of trains was added between Ludwigshafen and Neustadt. Omnibuses each linked two trains on the two isolated sections. Until 1865, there were no pure passenger trains in local traffic, but at most mixed trains . These often did not stop at all train stations. There was already a coal train on the Speyer – Ludwigshafen route in 1848, which was also used to transport passengers.

As early as 1853 there were continuous passenger trains on the Mainz – Paris route . In 1854 there were already three pairs of trains a day running between the two cities; a trip between Mainz and Paris took around 17 hours. With the completion of the Rhine-Nahe Railway , which was opened in stages, by the railway company of the same name in 1860, this connection was discontinued; accordingly a change in Neunkirchen was necessary from then on. In general, the Ludwigsbahn passenger trains no longer ran beyond Neunkirchen. In the same year, express trains ran on the Basel - Cologne route in the Ludwigshafen – Neustadt section . In 1865 three pairs of trains ran from Worms to Neunkirchen, two between Neustadt and Worms, one on the Homburg – Neunkirchen route. There was also a train from Kaiserslautern to Neunkirchen.

Palatinate Railways

After the Alsenz Valley Railway, which branched off in Hochspeyer , was opened in 1870 and 1871, local trains there initially continued along the Ludwig Railway to Kaiserslautern. There was no question of sustainable, supra-regional traffic in the east-west direction running via the Ludwigsbahn in the following decades, since the express trains on the Ludwigshafen – Neunkirchen route stopped at almost all subway stations. From mid-1872, the express trains from the Rhineland used the Neustadt – Hochspeyer section and the Alsenz line, as this connection was shorter than the previous one. In 1875 there was an express train on the Ludwigshafen – Neustadt – Metz – Paris route. Although a year later a direct connection from Ludwigshafen to Alsace was established in the form of the Schifferstadt – Wörth and Wörth – Strasbourg routes, most long-distance trains from Frankfurt continued to run to Neustadt and then via the Maximiliansbahn, always headed to Neustadt , due to the single-track equipment had to do. Some were winged there in order to unite a part of the train with those from the Alsenz valley, while the other part continued to run westward via the Ludwig Railway.

The local trains ran in 1884 on the Neunkirchen – Worms route. At the end of the 19th century, local transport in the true sense of the word first existed. In 1887 there were at least seven pairs of trains immediately west of Neustadt. Most of the express trains were limited to the Mainz – Ludwigshafen – Homburg – Neunkirchen route. Towards the end of the 19th century, the Orient Express also ran on the Ludwig Railway. From May 1901 there was an express train on the route Munich-Worms-Kaiserslautern-Metz-Paris on the Homburg-Kaiserslautern section .

Freight transport

Merchandise played only a minor role in the first few years of operation before the line was completed. They were preferably transported from Ludwigshafen to Neustadt. In addition, at that time there was great competition with the traffic of wagons. After its completion, the Ludwigsbahn carried mainly coal from the Saar region to the Rhine over its full length , which earned it the name coal railway . The transport of coal and iron was also the main source of income for the Ludwig Railway Company . In addition, it reported the income from coal transport separately from other freight transport in the annual reports. From 1851 to 1869, the transport of coal increased continuously along the Ludwig Railway. In 1854 it had the fourth highest volume of goods traffic within the German Confederation .

In 1871 the “normal” freight trains ran on the Ludwigsbahn in the Kaiserslautern – Mainz , Neunkirchen – Kaiserslautern, Homburg – Frankenthal routes . Ludwigshafen – Neunkirchen and Worms – Homburg. There was also a stone train on the Kaiserslautern – Ludwigshafen route and several coal trains on the Homburg – Neunkirchen, Kaiserslautern – Ludwigshafen, Neustadt – Neunkirchen, Kaiserslautern – Neustadt, Homburg – Neustadt, Ludwigshafen – Neunkirchen and Neunkirchen – Kaiserslautern routes. If necessary, so-called “supplement freight trains” were added between Neustadt and Ludwigshafen. Both Ludwigshafen and Kaiserslautern developed into important transshipment points for goods traffic, so that a marshalling yard was created in both places. The latter in particular experienced a significant economic boost immediately after the connection to the railway line, which led to the settlement of numerous companies. The transport of wood and the production of paper also played a major role between Kaiserslautern and Neustadt. A loading point was built in 1869 at the level of the Schöntal district of Neustadt . Further corresponding track connections followed. Towards the end of the 19th century, the Frankeneck timber loading area was added between Weidenthal and Lambrecht . The quarry in Weidenthal , which was owned by the Palatinate Railways and operated by the Palatinate Railways until 1906, also provided a large part of the freight traffic .

Incidents

- On October 28, 1863, an empty freight train pulled into Frankenstein station. At the end of it was a baggage car with 50 workers. A passenger train traveling in the same direction hit the freight train. Seven people died.

- In 1912 a railway accident occurred in Weidenthal. In this one person died, there were also several injured.

Vehicle use

The workshops in Kaiserslautern and Ludwigshafen were responsible for vehicle use . In 1860 the one in Neustadt was added. In the first few years after the opening of the line, locomotives from the machine works Emil Keßler or Maffei, which were given the numbers 1 to 8 and 21 and 9 to 20 , ran alternatively . These had names like Haardt , Vogesus , Denis and Alwens . In the 1850s, Crampton locomotives with numbers 26 to 63 were added.

From 1877 to 1891 locomotives of the P 1.II and P 1.III series hauled the express trains on the Ludwigshafen – Neunkirchen and Bingerbrück – Weißénburg routes. Just a decade later, the P 2.I performed this service. The P 3.I was also added towards the end of the 1890s . The G 1.I and G 2.II were used for freight traffic . The Palatinate Railways used the T 1 for both suburban and freight traffic . Towards the end of the 19th century, the express train service between Ludwigshafen and Hochspeyer was partly operated by locomotives of the Prussian state railways and the imperial railways in Alsace-Lorraine . From 1897 motor coaches of the types MC and MBCC could be found between Ludwigshafen and Neustadt .

Operating points

Ludwigshafen

The station was a terminus and was located in downtown Ludwigshafen. It was not far from the Rhine so that the coal, for which the route had primarily been built, could be reloaded onto ships for onward transport. With the opening of the line to Mainz in 1853 and the connection to Mannheim in 1867, it became a railway junction . Later it was named Ludwigshafen (Rhein) Hauptbahnhof , as a reaction to the incorporation of surrounding places, which had also received a rail connection. The fact that it was a terminus station increasingly turned out to be an obstacle to operations.

Mother city

The train station is a few kilometers further west of Mutterstadt. Since the latter was connected to the narrow-gauge railway line Ludwigshafen – Dannstadt from 1890 , the name "Mutterstadt Hauptbahnhof" was used unofficially for the station. As part of the expansion of the main line to four tracks, it received a new station building on the west side of the track system, which was used for passenger traffic, while the predecessor was exclusively responsible for freight traffic from then on.

Schifferstadt

The train station is located on the north-western outskirts of Schifferstadt . It was opened on June 11, 1847 as part of the Ludwigshafen - Neustadt section of the Ludwig Railway. At the same time, the branch line to Speyer went into operation, making Schifferstadt the first railway junction within the Palatinate. The branch line to Speyer was extended to Germersheim in 1864 and to Wörth in 1876 .

Bohl

The construction of the station took place south of the municipality of Böhl . It was not originally planned to be built; this was only agreed afterwards.

Hassloch

The station was built on the northern outskirts of Haßloch .

Neustadt a / d. Hardt

From 1847, the station was the terminus of the eastern Ludwigsbahn section for a period of two years . The first station building was made of wood. With the opening of the Maximiliansbahn it became the third railway junction within the Palatinate after Schifferstadt and Ludwigshafen. Later, the Palatinate Northern Railway was added, which initially ended in Bad Dürkheim and has led to Monsheim since 1873. For the latter, an extension of the railway system was necessary; accordingly, the original station building had to give way. From 1875 the station served as a state telegraph station. After the Alsenz Valley Railway was completed in 1871, the station also developed into an important long-distance traffic junction, which brought the city international fame. In the 1880s, the construction of a freight and marshalling yard began, the facilities of which were to the east of the Ludwig and Maximiliansbahn. From 1887 a connecting curve also led from this to the Maximiliansbahn, which allowed direct connections from Ludwigshafen to Weißenburg without changing direction.

Lambrecht

The train station is located on the northern outskirts of Lambrecht (Pfalz) . Stylistically, the station building corresponded to those train stations that were built in the Palatinate, especially in the second half of the 19th century.

Weidenthal

Weidenthal train station is located in the south of the Weidenthal district . The local quarry, with its own sidings, was an important freight customer. Were at it grindstones and millstones produced and shipped.

Frankenstein

The station is located on the western edge of the Frankenstein settlement . Immediately to the east of it is the Schlossberg tunnel . From December 2, 1848 to August 25, 1949, it was the eastern end point of the western Ludwigsbahn section coming from Bexbach. The interests of Paul Camille Denis , the builder of the Ludwigsbahn, played a major role in its creation , especially since he temporarily settled on site, acquired Diemerstein Castle and had a villa built in the immediate vicinity, the so-called Villa Denis . In view of the size of Frankenstein, the entrance building turned out to be architecturally very demanding, which is also due to Denis' influence. In terms of its construction, it resembles a castle .

Hochspeyer

The station was in the west of Hochspeyer near the local Heidestrasse . It was the original station of the municipality of Hochspeyer. Its construction was only decided afterwards. In the statistical yearbooks it was often listed as "Bahnhof am Kreuz". With the commissioning of the Alsenz Valley Railway and the new Hochspeyer station, it lost its function for passenger traffic and was given the new name "Althochspeyer". Out of consideration for a chemical company that had settled in its area, as well as because of its importance for the wood industry, it was retained as a freight yard .

Kaiserslautern

The station opened on July 1, 1848, when the Ludwig Railway Company opened the Homburg – Kaiserslautern section. At that time it was located south of the settlement area of the city of Kaiserslautern. It was not until six months later that the Ludwigsbahn was extended to Frankenstein, before the line from the Rheinschanze to Bexbach was open to traffic in 1849. Despite the great importance of the city, it was of rather subordinate importance in its early days, as it did not develop into a railway junction until 1875 with the opening of the Kaiserslautern – Enkenbach railway - which served both as a feeder line to the Alsenz Valley Railway and the Donnersberg Railway - and thus relatively late. It also gained in importance with the opening of the Lautertalbahn in 1883 and the completion of the Biebermühlbahn to Pirmasens in 1913.

Landstuhl

The train station is on the northern outskirts. It went into operation in 1848 with the Ludwigsbahn section from Kaiserslautern to Homburg. In this section it was always the most important station on the way. Since 1868, the line to Kusel branches off northwest of the station. This made the station the seventh railway junction within the Palatinate, after Schifferstadt, Ludwigshafen, Neustadt an der Haardt, Homburg (1857), Winden (1864) and Schwarzenacker (1866).

Main chair

The train station is in the north of the local community of Hauptstuhl .

Bruchmuehlbach

The train station is at the western end of Bruchmühlbach.

Homburg

The station was opened in 1848. When the Homburg – Zweibrücken railway was released in 1857, it became the fourth railway junction within what was then the Rhine Palatinate, after Schifferstadt (1847), Ludwigshafen (1853) and Neustadt (1855) .

Bexbach

At the time of its opening, the station formed the western end of operations for the Ludwig Railway, before the extension to Neunkirchen in Prussia was completed in 1850.

reception

In 1854 the Palatinate Ludwig Railway Society published a book called The Palatinate Railways and their Surroundings consisting of twenty-eight picturesque views, text and a map , which contains lithographs by the artist Friedrich Hohe from Munich. With the exception of a picture showing a train leaving a tunnel in Frankenstein, however, it does not contain any information about the railway operation itself, but mainly contains suggestions for excursions. Due to the fact that the route between Kaiserslautern and Neustadt passed several tunnels and the passenger cars of the time had no lighting, it was also very popular with lovers, who often hugged while driving through the tunnels. In 1967, Heinz Sturm wrote in his work “The Palatinate Railways” that it laid the “foundation for the upswing of the Palatinate railways and for the trust that they received from everyone” . In 1987 Werner Schreiner characterized the Ludwigsbahn as "economically successful" . This was "conducive to further railway plans in the Palatinate" . Fritz Engbarth describes them as "the backbone of the Palatinate railway traffic" . However, their story would be "incomplete without at least naming its builder [Denis]".

literature

- Fritz Engbarth: From the Ludwig Railway to the Integral Timed Timetable. 160 years of railways in the Palatinate . Ed .: Zweckverband SPNV Rheinland-Pfalz Süd. Kaiserslautern 2007 ( online [PDF; 4.1 MB ; accessed on December 1, 2012]).

- Klaus D. Holzborn : Railway areas Palatinate . transpress, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-344-70790-6 .

- Albert Mühl: The Pfalzbahn . 1st edition. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-8062-0301-6 .

- Palatinate-Ludwigs-Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft: The Palatinate Railways and their surroundings. Consisting of twenty-eight picturesque views, text and map . Ludwigshafen 1854. ("Official" travel guide of the Palatinate Ludwig Railway to its railway lines and their surroundings)

- Andreas M. Räntzsch: The railways in the Palatinate . Wolfgang Bleiweis, Schweinfurt 1997, ISBN 3-928786-61-X .

- Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways (= publications of the Palatinate Society for the Advancement of Science. Volume 53). New edition. pro MESSAGE, Ludwigshafen am Rhein 2005, ISBN 3-934845-26-6 .

Web links

- History of the Palatinate Ludwig Railway on kbs-670.de

- Ferdinand Stumm: Prospectus about the construction of a railway from Saarbrücken to the Rheinschanze, Saarbrücken 1836 on nbn-resolving.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ Railway stations according to the annual report of the management of the Palatinate Railways for the year 1869 ( map ), source of km and altitude information unknown.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Emich, Rolf Becker: The railways to Glan and Lauter . 1996, p. 12 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 83 .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 142 ff .

- ^ Klaus Detlef Holzborn: Railway Reviere Pfalz . 1993, p. 88 .

- ^ Fritz Engbarth: From the Ludwig Railway to the Integral Timetable. 160 years of railways in the Palatinate . 2007, p. 7 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 17th ff .

- ↑ Zweibrücker Wochenblatt , No. 18 of February 19, 1836, p. 58 restricted preview in the Google book search.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 21st ff .

- ↑ Wochenblatt für Zweibrücken, Homburg and Cusel , No. 157 of December 31, 1837, p. 3f. limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 53 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 54 .

- ^ Klaus Detlef Holzborn: Railway Reviere Pfalz . 1993, p. 8 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 165 .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 70 .

- ↑ a b Fritz Engbarth: From the Ludwig Railway to the Integral Timetable. 160 years of railways in the Palatinate . 2007, p. 5 .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 104 .

- ^ A b Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 67 f .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 68 f .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 58 f .

- ^ Fritz Engbarth: From the Ludwig Railway to the Integral Timetable. 160 years of railways in the Palatinate . 2007, p. 5 f .

- ↑ Main State Archives Munich (HSta MH), matriculation 13 227

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 79 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 87 ff .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 92 .

- ^ Gerhard Hitschler, Marcus Klein, Thomas Gierth: The vehicles and systems of the Neustadt Railway Museum on the Weinstrasse - the museum guide . 2010, p. 11 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 90 ff .

- ↑ saarpfalz-kreis.de: The "Ludwigsbahn" to Bexbach . Retrieved November 21, 2014 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 85 ff .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 93 f .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 96 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 113 ff .

- ↑ Information and pictures about the tunnels on route 3270 on eisenbahn-tunnelportale.de by Lothar Brill

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 117 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 146 .

- ↑ kbs-670.de: The course book route 670 - Chronicle - 1856 to 1865 . Retrieved November 20, 2014 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 149 .

- ↑ Franz Neumer: 150 years ago the first train ran through Hochspeyer . In: Homeland yearbook of the district of Kaiserslautern 1999 . 1999, p. 116 ff .

- ↑ kbs-670.de: The course book route 670 - Description - After completion and First World War . Retrieved November 26, 2013 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 231 .

- ^ Albert Mühl: The Pfalzbahn . 1982, p. 15th f .

- ↑ Railway Atlas Germany . 10th edition. Schweers + Wall, Cologne 2017, ISBN 3-921679-13-3 .

- ↑ kbs-670.de: The course book route 670 - route - kilometrage . Retrieved November 23, 2014 .

- ↑ kbs-670.de: The course book route 670 - Extras - The Einsiedlerhof operations center . (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on December 11, 2013 ; Retrieved November 20, 2014 .

- ↑ Andreas Räntzsc: The railway in the Palatinate. Documentation of their creation and development . 1997, p. 6 .

- ↑ kbs-670.de: The course book section 670 - Chronicle - 1966 to 1975 . Retrieved November 16, 2014 .

- ↑ Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar (Ed.): … In one line. Railway history in the Rhine-Neckar triangle . 2004, p. 26 .

- ↑ a b c kbs-670.de: The course book route 670 - operation - operational procedures and traffic: regional traffic development . Retrieved April 20, 2014 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 113 f .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 141 .

- ^ Albert Mühl: The Pfalzbahn . 1982, p. 11 f .

- ↑ Michael Heilmann, Werner Schreiner: 150 years Maximiliansbahn Neustadt-Strasbourg . 2005, p. 21 .

- ↑ Palatinate Railways: Train regulations. Service book for the staff. Summer service starting July 15, 1871 . 1871, p. 170 .

- ↑ kbs-670.de: The course book route 670 - operation - operational sequence and traffic: long-distance traffic development . Retrieved April 18, 2014 .

- ^ A b Albert Mühl: The Pfalzbahn . 1982, p. 113 f .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 117 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Fiegenbaum, Wolfgang Klee: Farewell to the rail. Disused railway lines from 1980 to 1990 . 1997, p. 216 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 190 .

- ↑ Reiner Frank: Railway in the Elmsteiner Valley then and now . 2001, p. 11 .

- ^ Albert Mühl: The Pfalzbahn . 1982, p. 14 .

- ↑ Michael Heilmann, Werner Schreiner: 150 years Maximiliansbahn Neustadt – Strasbourg . 2005, p. 114 ff .

- ↑ Heinz Friedel: Railway accidents in the district . In: Homeland yearbook of the district of Kaiserslautern 1999 . 1999, p. 65 .

- ↑ amiche.de: MUNICH - WACHENHEIM - PARIS . Retrieved November 23, 2014 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 95 .

- ^ A b Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 113 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 255 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 151 .

- ↑ Palatinate Railways: Train regulations. Service book for the staff. Summer service starting July 15, 1871 . 1871, p. 34 ff .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 142 .

- ↑ kbs-670.de: The course book route 670 - Description - After completion and First World War . Retrieved November 20, 2014 .

- ↑ Reiner Frank: Railway in the Elmsteiner Valley then and now . 2001, p. 9 .

- ^ Albert Mühl: The Pfalzbahn . 1982, p. 16 f .

- ↑ Heinz Friedel : Railway accidents in the district . In: Homeland yearbook of the district of Kaiserslautern 1999 . 1999, p. 64 .

- ↑ weidenthal.de: Chronology of a forest community - A piece of Weidenthaler Chronik by Arthur Eisenbarth (2004) . Retrieved November 20, 2014 .

- ↑ kbs-670.de: The course book route 670 - Chronicle - 1876 to 1885 . Retrieved November 20, 2014 .

- ^ Albert Mühl: The Pfalzbahn . 1982, p. 23 .

- ^ Albert Mühl: The Pfalzbahn . 1982, p. 154 .

- ^ Heinz Spielhoff: Locomotives of the Palatinate Railways. History of the Palatinate railways, express, passenger and freight locomotives, tender and narrow-gauge locomotives, multiple units . 2011, p. 23 ff .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 101 .

- ↑ kbs-670.de: The course book route 670 - operation - traction vehicle areas of application: steam locomotives . (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on November 4, 2014 ; accessed on November 21, 2014 .

- ^ Albert Mühl: The Pfalzbahn . 1982, p. 134 .

- ^ Albert Mühl: The Pfalzbahn . 1982, p. 92 ff .

- ^ Heinz Spielhoff: Locomotives of the Palatinate Railways. History of the Palatinate railways, express, passenger and freight locomotives, tender and narrow-gauge locomotives, multiple units . 2011, p. 193 .

- ^ Hermann Klein: The new main station in Ludwigshafen (Rhine) . In: Die Bundesbahn, 1969 (43) . 1969, p. 399 .

- ^ Klaus Detlef Holzborn: Railway Reviere Pfalz . 1993, p. 21 .

- ↑ General Directorate for Cultural Heritage Rhineland-Palatinate (ed.): Informational directory of cultural monuments - Rhein-Pfalz-Kreis. Mainz 2017, p. 21 (PDF; 6.5 MB; see Speyerer Straße 129).

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 125 .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 84 .

- ^ Klaus Detlef Holzborn: Railway Reviere Pfalz . 1993, p. 85 .

- ↑ Model and Railway Club Landau in der Pfalz e. V .: 125 years of Maximiliansbahn Neustadt / Weinstrasse – Landau / Pfalz . 1980, p. 47 .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 119 .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 118 .

- ↑ Reiner Frank: Railway in the Elmsteiner Valley then and now . 2001, p. 22nd ff .

- ↑ weidenthal.de: Chronology of a forest community - A piece of Weidenthaler Chronik by Arthur Eisenbarth (2004) . Retrieved October 1, 2015 .

- ^ Franz Neumer: 150 years ago the first train passed through Hochspeyer . In: Homeland yearbook of the district of Kaiserslautern 1999 . 1999, p. 117 .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 84 .

- ^ Klaus Detlef Holzborn: Railway Reviere Pfalz . 1993, p. 82 .

- ^ Klaus Detlef Holzborn: Railway Reviere Pfalz . 1993, p. 139 .

- ↑ Franz Neumer: 150 years ago the first train ran through Hochspeyer . In: Homeland yearbook of the district of Kaiserslautern 1999 . 1999, p. 117 f .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 83 f .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 87 .

- ↑ Heinz Sturm: The Palatinate Railways . 2005, p. 255 .

- ↑ Werner Schreiner: Paul Camille von Denis. European transport pioneer and builder of the Palatinate railways . 2010, p. 94 .

- ^ Fritz Engbarth: From the Ludwig Railway to the Integral Timed Timetable - 160 Years of the Railway in the Palatinate (2007) . 2007, p. 7 .