Prussian State Railways

Prussian State Railways refers to those railway companies that were owned or under the administration of the Kingdom of Prussia . There was no independent railway administration, rather the individual railway companies were each subject to the supervision of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry , from 1878 onwards by the separate Ministry of Public Works .

The official name was initially "Royal Prussian State Railways" (KPSt.E.), due to the merger with the Grand Ducal Hessian State Railways from 1897 until the end of the First World War, "Royal Prussian and Grand Ducal Hessian State Railways" (KPuGHSt.E. - Prussian-Hessian Railway Community ), and finally “ Prussian State Railway” (P.St.B.) until April 1, 1920, when the state railways were merged with the German Reichseisenbahnen .

Brief overview

The first Prussian railways, beginning with the Berlin-Potsdam Railway in 1838 (hence also called the “Stammbahn”), were private companies. The state of Prussia itself financed only around 1850 ( Königlich-Westfälische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft , Prussische Ostbahn ) and then again around 1875 ( Berliner Nordbahn and the military railway Marienfelde – Zossen – Jüterbog ) directly and to a significant extent new railway constructions.

Various private, commercially oriented railways were subjected to Prussian supervision , depending on the situation, through financial support, purchase or annexation after the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. Due to the favorable financial situation of Prussia, most private railways were nationalized on a large scale from 1880 until 1888. In view of these very different ownership and operating conditions, the nature of the Prussian State Railways was described in the Brockhaus Konversations-Lexikon in 1896 as a "mixed system".

The individual railways acted as independent companies that also developed their own vehicles and determined the operational organization themselves. How pronounced this independence was even when the Prussian railway network was at an advanced stage of development can be seen from a glance at a city map of Berlin from 1893. There, the Schlesische Bahnhof (the starting point of the Eastern Railway on the Berlin side since 1882) is shown, a few hundred meters apart , but nevertheless separate, the “main workshop of the Kgl. Railway Directorate Berlin "and the" main workshop of the Kgl. Eisenbahndirektion Bromberg ”of the Eastern Railway.

At the end of the First World War , the network of the state Prussian railways had a total length of almost 37,500 kilometers. The history of the Prussian State Railways ended in 1920 with the nationalization and takeover of the state railways in the Reichseisenbahn, which later became the Deutsche Reichsbahn .

In many cases the earlier existence of a so-called “ Royal Prussian Railway Administration ” is assumed, which organizationally never existed under such a name. In parlance, the entirety of the various railway authorities was referred to as the state railway administration. Vehicles of the Prussian railways that have been preserved in museums were also given emblems with the abbreviation “KPEV” during the restoration .

history

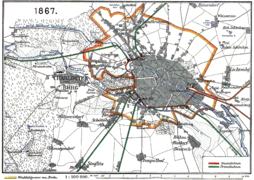

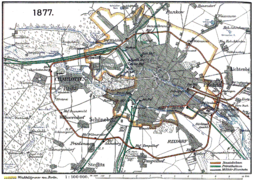

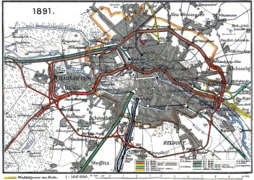

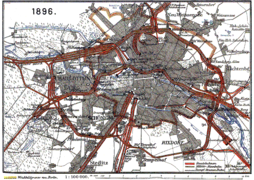

- Overview of the Berlin railways from 1846 to 1896 and their successive nationalization

Starting position

economy

To put it simply, there are two main economic areas in the then Prussian state: the extensive estates in the east and the up-and-coming large and heavy industry in the Rhine provinces and Silesia . The transport routes were of particular importance to both of them. The goods produced on the sparsely populated country estates had to be transported to the more distant, populous cities, and the Rhenish and Silesian industrial companies required a supply of raw materials on the one hand and the removal of the goods produced on the other. Mainly the waterways and horse-drawn carriages, in some cases horse-drawn trams, were available for this.

It was also essential that the Prussian economic area could no longer be viewed in isolation, as there were increasing imports and exports to and from there. The important waterways to the sea led on the Rhine to the Dutch ports, which levied high tariffs on the goods carried. It was also important that in England and the USA efficient rail systems for the transport of bulk goods already existed with a lead of 30 and 10 years respectively. It was possible that, thanks to these inexpensive transports, American grain, British and Belgian coal and pig iron, as well as other articles, were available in the Prussian area for less than equivalent domestic products.

There was thus an unavoidable need for rail connections from the eastern regions to Berlin and further west, as well as transport routes that could bypass the Dutch Rhine ports. The military also urgently wanted a rail link to the Russian border in the east.

First plans and applications

Even before the first machine-operated railway went into operation, there were plans and applications in Prussia to open individual, both private and state-financed railway lines.

So there were considerations about a railway from Elberfeld and Barmen to the Ruhr to supply these cities with coal, for which the state even carried out preparatory work in 1830. A cabinet order of June 1, 1833 approved the plan, but left the question unanswered as to whether it could be financed through the maritime trade .

On May 14, 1835, the mayor August Wilhelm Francke in Magdeburg also submitted a request to the privy councilor Rother in Berlin to found a railway stock company for the connection from Magdeburg to Leipzig. The construction concession was granted to the Magdeburg-Cöthen-Halle-Leipziger Eisenbahngesellschaft by the Prussian government on November 13, 1837, and the line was opened on August 18, 1840. The Prussian Railway Act of November 3, 1838 owes its creation to the preliminary negotiations . The company was connected to the Magdeburg-Halberstädter Eisenbahngesellschaft in 1876, but was ultimately bought up by the Kingdom of Prussia by law of December 20, 1879 and thus, like so many other railways built later, part of the Prussian state railways.

Politics until 1848

King Friedrich Wilhelm III. looked at the “railway” rather skeptically and is said to have said on the occasion of the opening of the private Berlin-Potsdamer Eisenbahn in 1838, the first mechanically operated railway in Prussia, “he couldn't expect much happiness from leaving Berlin in Potsdam a few hours earlier be".

Nevertheless, the politicians saw an increasing need for the railroad, and above all a railroad from Berlin east to the Russian border was desired by the military, which is very favored in Prussia. This was countered by the fact that there were insufficient funds available for an extensive railway construction, extensive railway construction by the state was therefore only possible with borrowing. According to the State Debt Act of January 17, 1820, government bonds required the approval of the estates. However, there was no assembly of estates for the kingdom in Prussia, only provincial estates.

Applications from the estates, such as those of the western provinces, to build a state railroad from Cologne to Eupen were rejected, and ultimately the construction of state railways was provisionally rejected by cabinet order on September 5, 1835. It remained so, although important personalities such as David Hansemann advocated the construction of the state railway.

The Prussian state was therefore initially dependent on the construction of privately financed railways. At the same time, however, it was important to him to exert influence on the railways if possible, or to be able to take them over himself at a later point in time. Corresponding provisions were formulated in the Prussian Railway Act of 1838. It was actually intended to promote the construction of private railways, but here some provisions had a considerably counterproductive effect. Paragraph 42, for example, gave the state the option of buying up a railway after 30 years and taking it over as its property. As a result, privately financed railways emerged, which were primarily commercially oriented.

King Friedrich Wilhelm IV., Who had ascended the throne in 1840, neither did his father want to share his power with an assembly of estates, and only after a long hesitation did he allow the formation of the United State Parliament of Deputies. However, apart from voting on his proposals, he gave him little authority. The result was that the project of borrowing for the construction of the railway, put to the vote by the king or the government, was rejected, primarily with the intention of forcing the king to grant the state parliament more extensive powers.

The von der Heydt era 1848–1862

First state railway construction

Eastern Railway

Around 1845 Friedrich Wilhelm IV showed himself ready to give in to the demands of his military for a rail link to the Russian border. In the absence of private interested parties, Friedrich Wilhelm IV initiated the preparatory work for the construction of the Eastern Railway “for the account of the future company”. However, the construction was immediately stopped again when the state parliament members refused to give him permission to borrow. Also at the United State Parliament convened in April 1847, the members of parliament voted with a two-thirds majority against a government loan for the Eastern Railway Project.

It was not until the revolutionary events of 1848 and the appointment of the banker August von der Heydt as Prussian trade minister - and thus responsible for the railways - that things got moving. In August 1849, v. d. Heydt presented a draft law on the construction of the Eastern Railway, which was passed on December 7, 1849. Previously, on November 5, 1849, the Royal Direction of the Eastern Railway had been set up in Bromberg . V. d. Heydt then arranged for the construction of the Ostbahn to be resumed, initially with funds from the “Railway Fund” and later also from various other financial resources.

From the Kreuz train station of the previously built private Stargard-Posener Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft (SPE), the first 145-kilometer section via Schneidemühl to Bromberg was put into operation on July 27, 1851. Further sections of the planned route were gradually built and the last section from Berlin Ostbahnhof via Strausberg to Gusow was opened on October 1, 1867. This provided the direct, 740-kilometer-long railway connection Berlin - Danzig - Königsberg and on via Insterburg to Eydtkuhnen to the German border. In addition, numerous parallel and short-cut routes were built, with which the Ostbahn covered a route network with a length of 2208 km in March 1880. It was one of the most important parts of the Prussian State Railways.

Royal Westphalian Railway

Around the 32-kilometer-long gap between Hamm and Lippstadt, between the line of the Münster-Hammer Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft, opened in 1848 towards the seaports, and the line of the Cologne-Minden-Thuringian Connection Railway Company that was under construction at the same time (KMTVEG), it was decided in 1850 to build the main line of the Royal Westphalian Railway as a state railway. By later taking over lines from other railways - especially the Emsland line Rheine – Emden - and own expansions, the KWE network grew to a length of around 600 kilometers.

Saarbrücken Railway

At the end of 1847, the Royal Commission for the Construction of the Saarbrücken Railway was commissioned to plan the connecting route between the Palatinate and French railway lines. The Royal Direction of the Saarbrücken Railway was set up for administration by decree of May 22, 1852. On November 16, 1852, the 37-kilometer route from the Bavarian border near Bexbach via Neunkirchen and Saarbrücken to the French border was put into operation.

Takeover of private railways

More years of vigorous state railway policy followed under Trade Minister August von der Heydt until 1859 . Although a liberal, v. d. Like the liberal finance minister Hansemann, Heydt is of the opinion that purely market-based railways would not be without negative consequences for the economy as a whole. August v. d. Heydt subsequently used appropriate paragraphs of the Prussian Railway Act to buy up private railways that had got into financial difficulties, not only on the territory of Prussia , but also in neighboring German countries.

The Stargard-Posener Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft (SPE) , founded in 1846, built a 170-kilometer single-track main line connecting the two provincial capitals of Szczecin and Poznan. Because the company's earnings did not meet expectations in the beginning, the state intervened and made the SPE subordinate to the Royal Directorate of the Eastern Railways in Bromberg in 1851, and then in 1857 to the Upper Silesian Railway, which was also temporarily administered by the state. The final date of nationalization is January 1, 1883 and July 1, 1886, although the joint-stock company still existed.

In the case of the Lower Silesian-Märkische Eisenbahn , the Prussian state took over the management of the railroad after acquiring a block of shares in 1850 and, in 1852, acquired the entire ownership of the railway. After it was taken over by the state, the NME became an instrument of Prussian railway policy beyond its own line operations. The technical and operational competencies of the NME, which are now in state hands, have now also been used to build or complete additional railways and their operation. With the operational potential, there was also a means of political leverage that could be used to influence the behavior of other societies.

- From 1857 the state of Prussia was able to use the railway line from Berlin to Frankfurt with the connecting line to Küstrin as a feeder to the initially unfinished Eastern Railway .

- Since the English imported coal was considerably cheaper than the Silesian coal , it was a particular concern of the state to promote the competitiveness of the domestic coal through a "one-penny tariff" for transports. The Upper Silesian Railway opposed this . Minister of Commerce v. d. Heydt thereupon put the board of directors under pressure in 1852 by threatening to commission the NME to carry out coal transports on the routes of the Upper Silesian Railway at a one-penny tariff. This procedure was formally permitted by Section 27 of the Prussian Railway Act (prEG). The Upper Silesian Railways gave way, with the result that their coal transports almost quadrupled and income also rose.

- When the first Berlin connecting line was completed on October 15, 1851 , the management of freight traffic was transferred to the NME.

- During the construction of the Berlin Northern Railway , the Berlin Northern Railway Company founded for this purpose had to be dissolved on December 15, 1875 due to a lack of financial reserves. The Prussian state acquired the unfinished railway and transferred the further construction work to the NME. Their "Royal Directorate of the Lower Silesian-Märkische Railway" was converted to the "Royal Railway Directorate of Berlin (KED)" on February 21, 1880, with a correspondingly expanded scope of duties.

- On July 17, 1871, the "New Connection Line", later the Berlin Ringbahn , built with state funds, was put into operation for freight traffic. The NME was entrusted with the construction and operational management.

The Railway Tax Act

The Prussian Railway Act also provided for the possibility of railway taxes. This also used v. d. Heydt, in order to raise funds for the acquisition of railways. He initiated a law against the protests of the railway shareholders, which provided for a progressive tax on the profits of the private railway companies and was promulgated on May 30, 1853. The income from the tax should be used to purchase common shares in the railroad companies. The same should be done with the dividends of the shares already in state hands. With this measure, the shareholders should, so to speak, already finance an upcoming nationalization of their railways in advance.

In 1862 v. d. Heydt was appointed Minister of Finance in the Bismarck Ministry and Count von Itzenplitz as his successor for the Department of Commerce.

The Itzenplitz era 1862–1873

From 1859 onwards, with the rise of the German Free Trade Party in Prussia, more liberal views prevailed, which also called for the state to withdraw from the railway system and for free enterprise for railway construction. Paragraph 6 of the law of May 30, 1853 was repealed with the effect that, from this point in time, the railway tax and the income from the shares already owned by the state flowed directly into the state budget.

Since Itzenplitz was also a supporter of the private railway concept, efforts to establish a state railway in Prussia were not pursued any further at this point. In addition, it also played a role that, after the constitutional conflict over military reform, which Bismarck had settled, no new point of contention was desired, as would have been the state spending on railway construction.

Gains from the Austro-Prussian War

In the spring of 1866, the now Finance Minister v. d. Heydt, contrary to his previously pursued railway policy, was forced to sell shares in the Cologne-Mindener Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft and some other railways. The money was needed for the Austro-Prussian War , which then led to the annexation of several German countries by Prussia. Their state railways also fell into Prussian ownership, namely the Bebraer Bahn , the Royal Hanoverian State Railways , the Nassau State Railroad and the Main-Neckar Railway . With these, the state railway network in Prussia grew by 1069 kilometers.

Railway concessions as objects of speculation

However, Itzenplitz's railway policy was largely characterized by a lack of principle, which von Itzenplitz even explicitly declared as part of the program. The liberal granting of concessions led, especially after the Franco-German War of 1870/1871, to a start-up boom in railway construction that attracted many speculators. Many of the licensed railways were already in distress in the foundation phase.

On January 14, 1873, at the first reading of the law , the MP Eduard Lasker reckoned with the railway policy of v. Exit Itzenplitz. He accused him of granting concessions at will. People like the speculator and “railroad king” Bethel Henry Strousberg could get whatever they wanted from the Minister of Commerce. Lasker named names of high-ranking personalities who had acquired concessions in order to sell them again for the so-called founder's profit, without really wanting to operate the railways. As a consequence of Lasker's speech, a commission of inquiry was set up, which came to the conclusion that from an economic point of view the nationalization of the railways was necessary. The immediate consequence of the report was the resignation of v. Itzenplitz on May 15, 1873.

Construction of the new connecting line in Berlin

Despite the passivity of Itzenplitz, the urgently needed construction of the new Berlin connecting line was initiated in 1867, which was to replace the inadequate and very annoying first Berlin connecting line on the streets of Berlin . Their route led from Moabit (today Westhafen ) via Stralau-Rummelsburg to Schöneberg to the station of the Berlin-Potsdamer Railway . The Lower Silesian-Märkische Eisenbahn was entrusted with the construction and the operational management . The Berlin Ringbahn later developed from this connecting line .

The Achenbach era 1873–1878

As the successor to von Itzenplitz, who had resigned, Heinrich Achenbach was appointed Minister for Trade, Industry and Public Works of Prussia. Achenbach resigned from the office in 1878 in order to follow the call to the position of Upper President of West Prussia.

Bismarck's railway policy

The Prussian Prime Minister Bismarck, who was also the German Chancellor , generally strived for the creation of a German Reichsbahn . In 1873, he took the events following the speech by MP Lasker as an opportunity to set up a Reich Railway Office in the same year .

As its director he appointed Albert Maybach , who was previously among other things chairman of the board of directors of the Upper Silesian Railway and from 1863 to 1867 director of the Eastern Railway . This was initially supposed to work out the draft of a Reich Railway Law, but this failed due to the resistance of the other German states.

At the turn of the year 1875/1876 it was also refused to unite the major railway connections in Germany into a closed system of railways owned by the Reich, a project that is also attributed to Bismarck. Maybach therefore resigned his position as President of the powerless Reich Railway Authority in 1876 and was appointed Undersecretary of State in the Prussian Ministry of Commerce.

After the failure of this project, Bismarck set out with all his energy to nationalize the private railways in Prussia. It is said that Bismarck intended, through the sheer superiority of a large Prussian state railway, to induce the other states to give in to the idea of the Reichsbahn.

Railway buildings from 1873–1878

Under Achenbach, the main events in the railway sector were the construction of the " Kanonenbahn " and the expansion of the connecting line to the Berlin Ringbahn .

From 1871 onwards, the military wanted a strategic railway to Wetzlar. The planned route had little or no civilian significance, but with the French reparations payments the Prussian state had the means to build this route, which was propagated as strategically important. Private plans to build a railway on the same route were rejected, such as the license application submitted on June 12, 1872 by the “Association for the Foundation of a Direct Railway from Berlin to Frankfurt am Main” to the Prussian Minister for Trade, Industry and Public Works. With the "law concerning the taking up of a loan of 120 million Thalers to expand, complete and better equip the state railway network, of June 11, 1873" the construction of this so-called cannon railway was resolved and the authorization for the necessary bonds was made. From August 15, 1873, the Prussian state built 513 kilometers of the 805-kilometer-long connection from Berlin to Metz .

The route of the new connecting line was completed by 1877 from Schöneberg station via Charlottenburg back to Moabit to form the 37-kilometer circuit of the Berlin Ringbahn .

During Achenbach's time, but apparently under the jurisdiction of the War Ministry, the construction of the Berlin-Marienfelde-Zossen military railway also fell . On January 9, 1873 , the War Ministry took the lead in obliging the Berlin-Dresden Railway to build a route to the west next to its tracks for the exclusive purposes of the military railway battalion.

The Maybach era 1878–1891

After Achenbach's resignation, the former head of the Reich Railway Authority and former Undersecretary of State Albert Maybach - initially on a temporary basis - took over the position of head of the Ministry of Commerce on March 30, 1878.

Takeover of the Berlin Stadtbahn

The takeover of the Berlin Stadtbahn by the state already financially involved as a shareholder took place when the "Berliner Stadteisenbahngesellschaft" became insolvent in 1878. The state took over the construction and operation at its own expense with the financial participation of the four resigned shareholders and the railways connected to the new line. Construction management was transferred to the newly founded “Royal Directorate of the Berlin City Railroad” on July 15, 1878, under the direction of Ernst Dircksen.

Ministry of Public Works

After the unsuccessful attempt with the Reich Railway Authority, von Bismarck transferred all Prussian railway affairs by law of August 7, 1878 to the Ministry of Public Works , which had been separated from the Department of Commerce and Industry in April 1878 and which Maybach, Minister of Commerce until July 1879, also headed in personal union. He was ennobled by the German Kaiser in 1888 . Albert von Maybach submitted his resignation as Minister of Public Works on May 1, 1891; his term of office ended on June 20, 1891.

Comprehensive nationalizations

Maybach immediately proposed to the Prussian House of Representatives to take over four important private railways with a total length of 3,500 kilometers. On January 1, 1880, Prussia took over the operation and administration of the Rhenish , Cologne-Minden and Magdeburg-Halberstädter railways . Shortly before, the reorganization of the now greatly enlarged state railway had been reorganized by law. At the top was the Ministry of Public Works as the "Ministry of Railways" . There were initially 11 railway directorates:

- Altona ( Hamburg )

- Berlin

- Wroclaw

- Bromberg

- Elberfeld ( Wuppertal )

- Erfurt

- Frankfurt / Main

- Hanover

- Cologne on the left bank of the Rhine

- Cologne on the right bank of the Rhine

- Magdeburg

The directorates were all the same and structured in three departments:

- Budget and cash management,

- Traffic and

- Construction and workshops.

There were 75 works offices. This structure was largely aligned with the previous situation: the existing directorates were taken over, operations offices replaced the previous private railway administrations and the communication between railway administration and customers hardly changed. The transition from the private to the state railway went smoothly.

The first major takeover in 1880 was followed by the Berlin-Hamburg Railway on January 1, 1884 with the approval of the governments of Hamburg and Mecklenburg-Schwerin . At this point in time, you were no longer a co-owner of the railway, just a supervisory authority. A “Royal Railway Directorate for the Administration of the Berlin-Hamburg Railway” began operations on May 17, 1884. In 1886 these companies were liquidated.

Most of the private railways were subsequently taken over, so that in 1885 around 11,000 kilometers of former private railways had passed into Prussian state ownership. While in 1870 only around a third of all Prussian railway lines were state-owned, in 1895 the state owned 26,483 kilometers of lines (including private railways under state administration). Private railways under their own management and non-Prussian state railways still covered 2,270 kilometers in Prussia at that time, which were operated by 58 administrations.

The Thielen era 1891–1902

Successor of v. Maybach became Karl von Thielen on June 22, 1891 , previously a member of the Wroclaw Railway Directorate and the Rheinische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft as well as President of the Elberfeld and Hanover Railway Directorate . Thielen was sometimes referred to as the "Minister of Railways".

Compared to his predecessors in this office, von Thielen had considerably reduced competencies - especially with regard to the tariff structure - which were justified by the diverse effects of changes on the other departments. In fact, in the meetings of the State Chancellery, the approval or refusal of special tariffs for certain cargo loads as well as the free travel regulations for higher-ranking officials were a recurring topic. From July 5, 1891, Thielen also became head of the Reich Railway Office and remained in both offices until June 23, 1902.

New service building of the Royal Railway Directorate Berlin

From 1892 to 1895 the new office building of the Royal Railway Directorate in Berlin was built on Schöneberger Ufer in the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg district for 1.6 million marks .

New administrative structure from 1895

Thielen made particular merits with the reorganization of the state railway administration, which came into force on April 1, 1895 after years of preparation. It was necessary because due to the strong increase in routes - through new construction and nationalization - the areas of responsibility of the directorates had become unwieldy and a considerable effort for internal communication arose. The number of the original 11 directorates has been increased to 20. The new directorates were:

At the same time, the two Cologne directorates (left and right bank of the Rhine) were merged, so that there were now a total of 20 directorates. The 75 company offices, the lower administrative level, were dissolved. Their responsibilities have been shifted partly to the directorates, partly to the inspections. From 1910, the inspections were then also referred to as "offices". This reform saved around 3,000 civil servants (17%). The Vossische Zeitung later wrote about the reform :

“The organization from 1895 simplified administration and enabled an orderly course of business. The organization of the railway directorates had the purpose of increasing the sense of responsibility and the willingness to work among the members of the directorates. This purpose has been fully achieved. "

1897 - Prussian-Hessian Railway Community

The Grand Duchy of Hessen-Darmstadt essentially consisted of two parts, the northern part of which, after 1866, was enclosed by the now Prussian province of Hessen-Nassau. The Hessische Ludwigs-Eisenbahngesellschaft (HLB), active in the southern parts of the country in the provinces of Starkenburg and Rheinhessen , was one of the largest private railways in Germany, but after the establishment of the Prussian State Railways in an economically difficult situation. After consultation between the HLB and the two states involved, the HLB merged on April 1, 1897 with the Prussian State Railroad under the common name "Prussian-Hessian Railway Operating and Financial Community". The management of the HLB was transformed into the 21st Prussian Railway Directorate, the Mainz Railway Directorate . Hessen was able to influence the filling of the leading civil service positions. The technology and operations, however, corresponded to Prussian regulations. All officials wore the Prussian uniform , but the Hessian ones were also allowed to wear a Hessian badge. Then, in 1897, the length of the Prussian state railways, including the lines outside Prussia, was given as 29,011 kilometers.

Economic importance at the turn of the century 1900

What financial or economic potential the state railways represented is shown by individual selected notes from the minutes of the Prussian State Ministry's meeting, at which the specialist ministers were present:

- January 15, 1894: Finance Minister Johannes von Miquel points out that the state railways represent a capital of six billion marks .

- December 30, 1896: In the financial year 1895/1896, wagons and locomotives for the state railways were ordered for 65 million marks "exclusively inland".

- November 16, 1897: the state railways achieved an additional income of 33 million marks since April 1, 1897 and the shortage of wagons has subsided.

- On December 16, 1897 it is reported that in November 1897 there was an additional income of 5.7 million marks in passenger traffic.

- April 16, 1898: The operating result of the state railways in the financial year 1897/1898 is 318.6 million marks in passenger traffic and 781.9 million marks in freight traffic, and thus 6.43% and 4.76% more.

- June 17, 1898: The state railway's additional income in May was 10.5 million marks. Miquel admonishes the railway administration to keep a moderate amount of expenditure, because you need their surpluses to balance the budget.

- November 18, 1899: The total income of the state railways in the budget year 1899 was an increase of 44.6 million marks over the previous year.

The Breitenbach era 1906–1918

On May 14, 1906, Reich Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow appointed Paul von Breitenbach - previously President of the Cologne Railway Directorate since 1903 - as Minister of Public Works and on May 21, 1906 as Head of the Reich Railway Office .

Central Railway Office

At the instigation of Wilhelm Hoff , the “Kgl. Eisenbahn-Zentralamt ”in Berlin, whose first president was Hoff. He was followed in 1912 by Richard Sarre in this post. The Central Railway Office in Prussia had the rank of Royal Railway Directorate and had been at Halleschen Ufer 35-36 in Berlin-Kreuzberg since April 1, 1913 . It was later converted into the Reichsbahn Central Office . The service building has not been preserved.

Beginnings of an electrical company

In order to research high-speed electric rail operations, the most important companies in electrical engineering, wagon construction as well as construction companies and their banks joined forces in 1899 to form the Study Society for Electric Express Railways (St.ES). The Prussian administration was also represented here as a partner and provided the 23-kilometer section between Marienfelde and Zossen on the military railway near Berlin for the practical tests . This was provided with a three-pole catenary for three-phase current with a voltage of 10,000 volts . In 1903, several test vehicles finally reached speeds of over 200 km / h on this route, one of which was a three-phase AEG multiple unit with a record speed of 210 km / h.

Since 1902 the Prussian railway administration and the AEG have been investigating the use of single-phase alternating current to drive rail vehicles. Between 1903 and 1906, a test operation with alternating voltage of 6 kilovolts and a frequency of 25 Hertz via an overhead line was set up on the four-kilometer suburban route between Niederschöneweide and Spindlersfeld . The system was then used from 1907 on the Hamburg-Altona city and suburban railway and, in parallel, on the Altona harbor railway , where the electrical voltage was increased to 6.3 kilovolts. The positive experiences prompted the Prussian railway administration to electrify the long-distance route between Dessau and Bitterfeld , and on January 18, 1911, an electric locomotive used on loan from the Grand Ducal Baden State Railroad ran the first trains.

The successful operation on the Dessau ↔ Bitterfeld route led to the approval of 9.9 million marks by the Prussian state parliament on June 30, 1911 for the electrification of the Silesian Mountain Railway between Görlitz and the Waldenburg coal district , the first electrical traffic on June 1, 1914 has been recorded. As a result, the Silesian Mountain Railway became an extensive test field for electric railway operations under difficult geographic conditions.

On June 9, 1913, the Prussian state parliament approved 25 million marks for a possible electrification of the Berlin light rail with 15 kilovolt 16 ⅔ Hertz (see traction current ). Ten of these electric locomotives, four railcars and a number of motorized bogies were to be procured. Until the outbreak of the First World War , however, only the motorized drive units and two electric locomotives were completed, which were then used in Silesia.

By 1920, a total of around 150 kilometers of mainline lines in Silesia and Central Germany and almost 40 kilometers of suburban railways in Berlin and Hamburg and Altona / Elbe were electrified. The following power systems were used:

- Suburban railway Altona - Hamburg: 6.3 kilovolt 25 Hertz alternating voltage , overhead line

- Suburban railway Berlin: 550 or 750 volts DC voltage, power rails

- Berlin (military railway ): 10 kilovolt 50 Hertz three- phase voltage , three-pole overhead line

- Central Germany and Silesia: 15 kilovolt 16 ⅔ Hertz alternating voltage , overhead line

First World War

From 1914 the operation of the Prussian State Railways was increasingly influenced by the events of the First World War. These include restrictions on spending, requisitions of railway material for war purposes, e.g. B. the copper contact wire of newly installed overhead lines , restriction of public operations in favor of military transports, as well as resistance of the railway personnel to the associated operating conditions.

From the meeting of the Prussian State Ministry on October 5, 1918:

“Breitenbach wants to leave as soon as possible because he cannot participate in the radicalization [...] of the government. Before the war he was the sharpest opponent of the SPD and since 1914 he had to tolerate their intrusion [...] into the railroad workers. But now he is not ready to agree to a now developing universal validity of a Chamber of Labor law. A conflict between the Reich and Prussia can only be prevented by resigning "

On November 8, 1918, Breitenbach submitted his resignation.

End of the Prussian state railways

1919 - losses from the First World War

By the end of the First World War , the distance increased to almost 37,500 kilometers. After the First World War, Prussia had to cede 4,558 kilometers of railway lines to Poland (4,115 kilometers), Gdansk (145 kilometers), Belgium (129 kilometers), the Memel region (137 kilometers) and Czechoslovakia (31 kilometers) by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 another 250 kilometers to Denmark and 298 kilometers due to the separation of the Saarland from France .

1920 - transition to the Reichseisenbahnen

Through the State Treaty of March 31, 1920 between the Reich and the states of Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Württemberg, Baden, Hesse, Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Oldenburg and the law on the transition of the railways to the Reich of April 30, 1920 (RGBl. 1920 I, p. 773) with effect from April 1, 1920, the state railways of these countries and thus also Prussia were transferred to the Reichseisenbahnen, the later Deutsche Reichsbahn .

structure

Leadership at the government level

After 1848, the banker August von der Heydt, in his role as Prussian trade minister, was named responsible for the railways. As v. d. Heydt moved to the Ministry of Finance in 1862, Count von Itzenplitz was his successor, after whose resignation in 1873 Achenbach again followed and stayed until 1878.

After the failure of his plans for a Reichsbahn, the then Prussian Prime Minister and (from 1871) Reich Chancellor Otto von Bismarck transferred all Prussian railway affairs to the newly created Ministry of Public Works by law of August 7, 1878 and appointed the former head of the Reich Railway Office Albert von Maybach to Minister. Von Maybach submitted his resignation on May 1, 1891 and was dismissed on June 20, 1891.

Successor of v. Maybach became Karl von Thielen on June 22, 1891 , followed by Hermann von Budde until April 28, 1906, followed again by Paul von Breitenbach from May 11, 1906 to November 13, 1918. Breitenbach was previously a. a. in Mainz president of the "Royal Prussian and Grand Ducal Hessian Railway Directorate" of the United Prussian and Hessian State Railways , and from 1903 president of the "Royal Railway Directorate of Cologne". After Breitenbach's resignation, Wilhelm Hoff became Minister of Public Works on November 14, 1918, but resigned himself on March 25, 1919 due to political differences of opinion. His successor as " Minister of Railways" was Rudolf Oeser , who remained in this office until April 21, 1921 and later became General Director of the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft from 1924 to 1926 .

“As a model for a state railway administration, the organization of the administration of the Prussian state railways, which came into being through a decree of November 24, 1879, is of the greatest importance, both with regard to the scope of the Prussian state railway network and because it has served as a model for other state railway administrations. The same is based on the principle of decentralization with three administrative bodies: the minister in the central instance, the railroad directorates as middle heirs and the railway company offices as district administrative authorities.

The minister is in charge of the administration; it decides on the complaints against the orders and resolutions of the directorates. However, only those matters are reserved for his special approval which by their nature belong to the competence of the ministerial authority or which, due to their particular importance or financial implications, require a uniform regulation. New railway lines must not be opened before the Minister's approval has been given after their revision and acceptance.

An institution peculiar to the Prussian administration and now also being imitated by other state railroad administrations is the organization of advisory boards through which those interested in transport can participate in the administration of E. to secure a solution to their tasks that corresponds to the transport needs as much as possible. For this purpose, the law of June 1, 1882 set up a state railway council for the central administration of the Prussian state railways and district railway councils for advisory participation in the state railway directorates. The State Railway Council consists of a chairman to be appointed by the king and his deputy, ten members to be appointed by the ministries of public works, finance, trade and agriculture (they may not be direct civil servants) and representatives of the provinces and some larger ones Cities, the election of these members is effected by representatives of agriculture, forestry, industry and trade by the district railway councils. The State Railway Council examines all important questions relating to public transport; in addition, all matters relating to the admission or refusal of exceptional and differential tariffs, general tariff provisions and the annual overview of normal transport charges to be attached to the state budget are presented to him. The district railway councils are composed of a corresponding number of representatives of the trade, industry and agriculture and forestry, who are elected by the provincial committees for a period of three years after hearing the chambers of commerce and central agricultural associations. They form an advisory body for the state railway directorates in all important questions affecting the transport interests of the narrower district, namely also the timetable and Tariff matters. "

Administrative Directorates

The administrations of the larger railways were reorganized into independent directorates, which were referred to as "Royal Railway Directorates", "KED" for short and later as " Railway Directorates " ("ED"). As an example of the establishment of such a directorate, that of the Berlin directorate after the restructuring of April 1, 1895:

It was divided into nine factory inspections, three machine inspections, 13 workshop inspections, a telegraph inspection and four traffic inspections. In addition to the President, the workforce consisted of 15 members of the Board of Directors, ten unskilled workers, an accounting director, an accounting officer and 580 office workers.

The division made with the restructuring of 1895 was essentially taken over by the subsequent Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft , the Deutsche Bundesbahn and the Deutsche Reichsbahn .

For some of the railway directorates in this table, previous construction dates are given in the literature; these then mostly concern the directorates of the former private railways.

| KED | Establishment | comment |

|---|---|---|

| Kgl. Military Railway Directorate | October 15, 1875 | Marienfelde – Zossen – Jüterbog military railway , disbanded in 1919 |

| Berlin city railway | July 15, 1878 | "Kgl. Directorate of the Berlin City Railway ”, dissolved in 1882 |

| Bromberg | April 1, 1880 | previously "Kgl. Direction der Ostbahn zu Bromberg ”founded November 5, 1849 |

| Berlin | April 1, 1880 | formerly “Kgl. Direction of the Lower Silesian-Märkische Railway ”, founded on January 1st, 1852 |

| Cologne on the right bank of the Rhine | April 1, 1880 | dissolved on April 1, 1895, transition to the left rh. |

| Cologne on the left bank of the Rhine | April 1, 1880 | on April 1, 1895 merged to KED Cologne |

| Frankfurt (M) | April 1, 1880 | - |

| Hanover | April 1, 1880 | - |

| Magdeburg | April 1, 1880 | - |

| Erfurt | May 1, 1882 | - |

| Katowice | January 1, 1883 | disbanded in October 1921 |

| Altona | March 1, 1884 | Takeover of the management of the Altona-Kieler Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft , from January 1 (or July 1) 1887 also its acquisition |

| Wroclaw | April 1, 1895 | - |

| Cassel | April 1, 1895 | - |

| Danzig | April 1, 1895 | - |

| Elberfeld | April 1, 1895 | - |

| eat | April 1, 1895 | - |

| Halle (Saale) | April 1, 1895 | - |

| Koenigsberg | April 1, 1895 | - |

| Muenster | April 1, 1895 | - |

| Poses | April 1, 1895 | - |

| Saarbrücken | April 1, 1895 | No successor to the Saarbrücken Railway Directorate on May 22, 1852 |

| Szczecin | April 1, 1895 | - |

| Mainz | February 1, 1897 | Kgl. Prussia. and Grand Duke. Hessian ED |

| Kgl. Railway Central Office Berlin | April 1, 1907 | in the rank of a KED |

Network structure

East-west orientation with the center of Berlin

In the final stages before the First World War, the individual railways of the Prussian state largely had an east-west orientation with the center of Berlin. The large long-distance railway lines, which were gradually built or acquired, started here in a star shape from separate terminal stations (starting in the south, counterclockwise):

- the Berlin-Potsdam railway from Potsdamer Bahnhof with continuation to Magdeburg ,

- the Berlin-Anhalt Railway and Berlin-Dresden Railway from the Anhalter Bahnhof ,

- the Berlin-Görlitzer Railway from Görlitzer Bahnhof ,

- the Berlin-Frankfurter Eisenbahn from Frankfurter Bahnhof (later Schlesischer Bahnhof , today Berlin Ostbf ) to Frankfurt (Oder) with continuation to the Upper Silesian coal area,

- the Prussian Eastern Railway from 1852 from the former Ostbahnhof , later from the Schlesisches Bahnhof to Eydtkuhnen on the Russian border,

- the Berlin-Stettin Railway from Stettiner Bahnhof (later Nordbahnhof ) to Stettin with continuation to Gdansk ,

- the Berlin-Lehrter Railway from Lehrter Bahnhof (today Berlin Hbf ) to Lehrte with continuation to Hanover and the Ruhr area ,

- the Berlin-Hamburg railway from the Hamburger Bahnhof , from October 1884 from the Lehrter Bahnhof to Hamburg with continuation to Kiel via the Hamburg-Altona connecting railway and the Altona-Kiel railway .

From 1878 the network of the Berlin city railway (the later S-Bahn Berlin ) was built, which until 1882 had its own "Royal Directorate of the Berlin City Railway".

Western north-south axis

After the takeover of the Hannöverschen , Nassauische Staatsbahn and Altona-Kieler Eisenbahn in 1866, as well as the Cologne-Mindener , Bergisch-Märkische and Rheinische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft, including the companies they had previously taken over, the Prussian State Railways also had a western route network from the North and Baltic Seas to the Rhine . The northern endpoints were Kiel , Emden and Bremen , in the south the network extended to Bingerbrück , Wetzlar , Trier and Kassel .

Areas with high network density

Areas with a particularly high network density were the area between Cologne and Dortmund , and in each case in the catchment area of Frankfurt am Main , Berlin and Upper Silesia .

State-financed railways and routes during construction

- Berlin connection line , nine kilometers from Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin to Potsdamer Tor (today Potsdamer Platz ), opened in 1851

- Prussian Eastern Railway , main line Berlin ↔ Eydtkuhnen 740 kilometers, completed in 1867, plus another 500 kilometers of branch lines (total network with acquired railways 2,210 kilometers)

- Royal Westphalian Railway Company , Hamm ↔ Warburg railway line 126 kilometers, completed in 1853

- Saarbrücken Railway , 36 kilometers between Bexbach and Saarbrücken / French border, commissioned on November 16, 1852

- New Berlin connecting line, later the Berlin ring line with a total of 37.5 kilometers, first section opened in 1871

- Military railway Marienfelde - Zossen - Jüterbog , 70 kilometers, route Berlin ↔ Zossen completed on October 15, 1875

- " Kanonenbahn ", a total of 513 kilometers of connecting lines between Berlin and Metz 1873–1879

- Berliner Nordbahn , 223 kilometers from Berlin to Stralsund 1876, takeover of the unfinished building in 1875

- Daadetalbahn 1885

- Oberwesterwaldbahn 1885

- Hamm-Osterfelder Bahn 1905

Railways and routes bought up or taken over by state treaty

- Lower Silesian-Märkische Railway Company (1852)

- Münster-Hammer Railway Company (1855)

- Duke of Brunswick State Railroad after conversion into a private railway company, 1870 with effect from January 1, 1869

- Magdeburg-Halberstädter Eisenbahngesellschaft with the previously affiliated Magdeburg-Köthen-Halle-Leipziger Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft and later participation in half of Leipzig Central Station in 1879

- Rheinische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft (January 1, 1880, with 1,295 kilometers, 507 locomotives and 14,186 wagons. The company was dissolved on January 1, 1886)

- Homburg Railway Company (January 1, 1880)

- Berlin-Szczecin Railway (February 1, 1880)

- Berlin-Potsdam-Magdeburg Railway on April 1, 1880

- Bergisch-Märkische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft (March 28, 1882, with 1,336 kilometers, 768 locomotives and 21,607 wagons)

- Anhaltische Leopoldsbahn 1882 (indirectly via the Berlin-Anhaltische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft)

- Berlin-Görlitzer Railway Company 1882

- Berlin-Anhaltische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft 1886, after the management was taken over in 1882

- Thuringian Railway Company on July 1, 1886 after the management was taken over on January 1, 1882.

- Altona-Kiel Railway Company (1886)

- Berlin-Hamburg railway takeover in sections from 1884

- Berlin-Dresden Railway Company (April 1, 1887)

- Aachen-Jülich Railway (May 1, 1887)

- Hessian Ludwig Railway Company (1897 in association with the Prussian-Hessian Railway Community )

- Glückstadt-Elmshorn Railway Company on July 1, 1890

- Werra Railway Company (July 16, 1895 to October 31, 1895)

- Dortmund-Gronau-Enscheder Railway Company (1903)

- Kronberg Railway (1914)

Transfer of ownership of state railways in other countries after the war of 1866

- Bebraer Bahn (Kurhessische Staatsbahn) 1866, then Frankfurt-Bebraer Eisenbahn.

- Royal Hanover State Railways 1866

- Nassau State Railways 1866

- Main-Neckar-Eisenbahn 1866 (share of Hessen-Darmstadt acquired in 1896)

- Main-Weser-Bahn 1866 (portion of Hessen-Darmstadt acquired in 1880)

- Frankfurt-Offenbacher Eisenbahn 1866 (Hesse-Darmstadt's share only acquired in 1868)

As of 1895

In 1895 the State of Prussia operated 26,483 kilometers of its own state railways as well as private railways under state administration. A further 2,207 kilometers of state railways were under construction and prepared for construction.

From August 1, 1897, a joint operation was established with the state railways of the Grand Duchy of Hesse, which was called the United Prussian and Hessian State Railways .

Rolling material

Steam locomotives

Origin and type distribution

For the most part, the locomotives classified in the Prussian designation system were not built under state control, but were procured independently by the respective railway companies. In many cases, they were only transferred to the Prussian vehicle fleet when the owner changed hands at a later date. This explains the extremely high number of around 80 types and variants, most of which were created between the years of construction from 1877 to around 1895. In 1880 the Prussian standards were set up in order to keep the number of locomotive types lower in the future.

The distribution according to type variants or different designs shows a clear predominance of tank locomotives . These were procured in widely differing, sometimes high numbers of around 9,000. This reflects a structure that largely consisted of disjointed small railways, for which no locomotives with a long range - i.e. not with an additional tender - had to be procured. In terms of the number of units, the freight locomotives dominated with around 12,000 out of a total of around 30,000 locomotives in the Prussian state stock.

Designation system

According to Hütter and Pieper , the original designation system for the Prussian locomotives was essentially adopted by the Ostbahn . After that, the locomotives only had company numbers, without the generic symbol. However, the purpose of use could be derived from the establishment number through the following breakdown:

| design type | numbering |

|---|---|

| Uncoupled locomotives | 1-99 |

| Coupled express and passenger locomotives | 100-499 |

| Double-coupled freight train locomotives | 500-799 |

| 3-way coupled freight train locomotives | 800-1399 |

| 2-fold coupled tank locomotives | 1400-1699 |

| 3-way coupled tank locomotives | 1700-1899 |

| Special designs | 1900-1999 |

Since each directorate numbered its locomotives independently on this basis, there was, for example, a locomotive number 120 almost everywhere. Therefore, in addition to the company number, the directorate was also given to distinguish it. The complete designation for a locomotive with the number "120" was thus about "Hanover 120", "Cöln links Rheinisch 120" etc. It soon turned out that the structure was too tight, as more locomotives were put into service over time were as the number range provided it. On the other hand, new types were added for which no numbers were intended, for example the four-coupler. This led to the fact that, over time, the locomotives were provided with the numbers that were just free outside the order.

This led to the introduction of a new system in 1906. The group letters "S", "P", "G" and "T" were used for "express", "passenger", "freight" and "tank locomotives" , plus a genre number with which the main groups were determined:

- Medium-power locomotives should be assigned to the groups of three S3, P3, G3 and T3, weaker ones got lower numbers and more powerful ones got higher numbers.

- Superheated steam locomotives should also be given an even group number, while steam locomotives that are similar in design should have the group number below.

- Subgroups were introduced later, which were identified by superscript numbers.

- In addition, the groups were assigned unique areas for the establishment number.

Nevertheless, the complete name still contained the generic letter and number, the director's name and the company number.

Groups 1 to 3 mainly consisted of the old private railroad locomotives, whereby the classification was left to the individual departments. In the lower groups there were a wide variety of designs with, in some cases, different axis sequences. Initially, there was no question of a uniform class structure. It was expected that over time the older locomotives would be decommissioned, so that only the newer normal locomotives remained as a properly integrated class.

The Prussian State Railways, like all other German state railways, were initially placed under the sovereignty of the German Reich after 1920 and then merged into the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft in 1924 . A number of locomotives previously ordered by Prussia were delivered until 1926 and were therefore still defined as "Prussian" locomotive types in the Reichsbahn's inventory until they were finally redesignated.

Electric multiple units

On October 1, 1907, the first electric multiple units were used on the Hamburg-Altona urban and suburban railway line . By 1913, the Prussian Railway Directorate had procured a total of 88 multiple units for this suburban traffic, each consisting of a motor car and a trailer.

In April 1914, the Prussian State Railways took off the railcars with the number ET 831 / 831a / 832 on the Silesian Mountain Railway from Görlitz via Waldenburg to Breslau , the remaining five railcars ET 833 / 833a / 842 to ET 841 / 841a / 842 were until June Commissioned in 1914.

Between 1907 and 1916, six individual battery-powered railcars and a series of ten battery-powered railcars of the type AT 569-578 were also purchased.

Electric locomotives

In 1910 the Prussian state railways procured individual electric locomotives for the first time. They were initially given the generic designations “WSL” and company numbers from 10201 for AC express train locomotives and “WGL” and company numbers from 10501 for AC freight train locomotives. From 1911 a system based on the steam locomotive designations was introduced with the generic designations:

- ES with company numbers from 1: express train locomotives

- EP with company numbers from 201: passenger locomotives

- EG with company numbers from 501: freight locomotives.

Multi-part locomotives were marked with lower case letters. The company numbers were always given with the prefix home administration to avoid confusion.

As early as 1914, after a few examples with the express train locomotives ES9 to ES19 (11 units) and the freight locomotives EG 511 to EG 537 (27 units), larger series were procured for the Magdeburg-Leipzig-Halle route.

From 1915 the three-part EG 538abc to EG 549abc followed for the Wroclaw Railway Directorate and its Silesian Mountain Railway , of which twelve were delivered until after the First World War.

From 1923, eleven electric passenger locomotives EP 236 to EP 246 and 25 of the two-part freight locomotives EG 701 to EG 725 were built. The last two types were taken over into the inventory of the newly founded DRG with their Bavarian and Prussian Länderbahn numbers and were soon redesignated as the E 50 and E 77 series.

A total of 170 electric locomotives were used on the Prussian state railways, which were divided into 30 different types.

Steam and combustion engine railcars

The Prussian state railways still had three steam railcars, the 20-vehicle internal combustion engine railcar series VT 1 to VT 20 and the three railcars "VT 101 to VT 103 Hanover" with diesel engines and 60 seats each.

Passenger cars

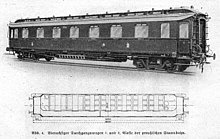

Compartment car

Until around 1880, two-axle compartment cars with doors for each compartment and no connections between the compartments were common. After the end of the nationalization wave around 1895, the quieter three-axle vehicles were purchased. For this purpose, so-called standard components were set up, which contained wagons of the two-, three- and, from 1895, four-axle designs, which with their numerous doors were popularly known as "hundred- door vehicles ". In order to allow access to an abortion , passages were created between the compartments later.

The compartment cars of the two- and three-axle designs were first used in all types of trains. With the advent of express train wagons, compartment wagons were mainly used in passenger trains on main routes and in urban traffic . Here, in addition to the faster change of passengers, the fact that the platforms of stations on main routes could only be entered with a valid ticket and only shortly before the train "departed", which shifted the control process from the conductor to the station staff, made itself felt positively.

From 1910 the previous kerosene lighting was converted to gas incandescent lighting, and steel construction was also used instead of wood. The wagons of the Prussian State Railways were equipped with standard bogies with double, later triple suspension. Most of the four-axle wagons were 18.55 meters long. When brakes were first air brakes of type Westinghouse Knorr-Bremse unit used from the turn of the century. The handbrake was housed in a separate brakeman's house at one end of the car.

| Sample sheet | Type pr. | Type DR | Construction year | Number of cars |

Number of seats per class |

Number of abortions |

Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3091 B | FIG | B4 pr-95 | 1895 | 350 | 10/31 | 3 | Length 18.15 m |

| 3092 B | ABCC | BC4 pr-98 | 1898 | 200 | 5/21/32 | 4th | Length 18.20 m |

| 3093 B | CC | C4 pr-94 | 1895 | 350 | 80 | 3 | Length 17.88 m |

| TUE 21 | FIG | B4 pr-02 | 1902 | 200 | 10/31 | 3 | |

| Tuesday 22 | ABCC | BC4 pr-98a | 1898 | 200 | 50/31/32 | 4th | |

| Tuesday 23 | CC | C4 pr-02 | 1902 | 300 | 76 | 5 | |

| Ib 01 | FIG | B4 pr-04 | 1904 | 350 | 10/31 | 3 | |

| - | ABCC | BC pr-04 | 1904 | 250 | 5/21/32 | 4th | |

| Ib 03 | BBC | BC pr-05 | 1905 | 100 | 20/48 | 5 | |

| Ib 04 | CC | C4 pr-04 | 1904 | 450 | 76 | 5 | |

| Ib 04a | CC | C pr-12 / 12a | 1911 | 650 | 76 | 4th | Length 18.62 m |

| BB | B4 pr-18 | 1918 | 40 | 47 | 3 | Length 19.20 m | |

| - | CC | C4 pr-18 | 1918 | 86 | 76 | 4th |

Express train car

From around 1880 dining cars were placed on the express and courier trains, but the train restaurant could only be visited at a train station stop where passengers could change cars. It was the Prussian State Railways that introduced a new type of car that was revolutionary for the time in 1891. The new, on average 20.5 meter long car design combined the advantages of the American chair-car principle with the familiar European compartment arrangement. Instead of having two side doors from the outside, each compartment in this four-axle car with two bogies was now accessible from the inside of the car via a side aisle. In addition, the platforms at the end of the car were closed. Between the individual wagons, passageways protected with bellows at the ends of the wagons enabled passage through the entire train: the through-car, or D-car for short, was born. The "D" was also adopted for a new type of train in express train traffic: the express train . With the D 31/32 , the first train with this type of wagon ran from May 1, 1892 on the Berlin Potsdamer Bahnhof - Magdeburg - Hildesheim - Cologne route with four wagons of the first and second wagon classes . These new express trains offered a higher level of comfort than the previous express trains, which often, but not always, had three car classes.

At first only first class (A) and second class (B) cars of the types A4ü, AB4ü, and B4ü were procured. The new trains were well received by the public. For this reason, more new express train series were quickly ordered in Prussia. Since 1894, the express trains from Berlin to East Prussia and Warsaw also operated with the third class of car. Up to the turn of the century, open-plan cars with a central aisle were also procured, but with a protected walkway, which also enabled passage on the train and was therefore used in express trains. The compartment cars were preferred for night travel, the open-plan cars were reserved for day trains.

In addition, dining cars and sleeping cars were also used, which corresponded to the D-type car. Most of these wagons were managed by the KPEV itself; in other German countries, as is common in Europe, the International Sleeping Car Company (ISG) was responsible, although their own wagons were adapted to the design of the Länderbahn wagons. There were also baggage and mail wagons in the same style as the express train wagons.

From 1893 to 1909, in addition to the state railways of Bavaria, Oldenburg and Saxony, Prussia also procured shorter three-axle express train passenger cars that were otherwise similar to the four-axle vehicles. Prussia ordered 22 AB3ü cars, which were originally developed in Bavaria. However, the cars did not prove themselves in express train traffic. They were withdrawn from the fast long-distance trains after a short time.

At the beginning of the century, the Prussians switched to six-axle express train cars, which offered increased smoothness. From 1909, bogies of the type that were first used by the American Pennsylvania Railroad were used, and were called gooseneck bogies because of the gooseneck-shaped compensating beams.

From 1913 to 1922, a total of 984 cars of various designs were procured by the Prussian State Railways.

Freight wagons

Prussia was trend-setting in Germany in the development and construction of freight wagons, as it owned more freight wagons than all the other regional railways combined. An overview of the most important types can be found in the chapter on standards .

See also

literature

- Ingo Hütter, Oskar Pieper: Complete directory of German locomotives . Part 1: Prussia until 1906. Volume 1 . Schweers + Wall, Aachen 1992, ISBN 3-921679-73-7 .

- Ingo Hütter, Oskar Pieper: Complete directory of German locomotives . Part 1: Prussia until 1906. Volume 2 . Schweers + Wall, Aachen 1996, ISBN 3-921679-74-5 .

- Wolfgang Klee: Prussian railway history . Kohlhammer Edition Eisenbahn, Stuttgart a. a. 1982, ISBN 3-17-007466-0 .

- Herman Klomfass: The development of the state railway system in Prussia: A contribution to the railway history of Germany . Schröder & Jeve, Hamburg 1901.

- Kgl. Pr. Minister d. public Work (Ed.): Berlin and his railways 1846–1896 . Springer-Verlag , Berlin 1896, ISBN 3-88245-106-8 (reprint).

- Hans-Ludwig Leers: The development of the traffic in the industrial conurbation of the cities and communities of the Wuppertal in the 19th and early 20th century . A contribution to the history of traffic in the Wuppertal. Kovac, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-8300-2609-9 (also: PhD dissertation University of Wuppertal 2005).

- Elfriede Rehbein : On the character of Prussian railway policy from its beginnings up to 1879 . Dresden, 1953.

- Prussian railways. In: Viktor von Röll (ed.): Encyclopedia of the Railway System . 2nd Edition. Volume 8: Passenger tunnel - Schynige Platte Railway . Urban & Schwarzenberg, Berlin / Vienna 1917, p. 116 ff. (With map).

- Prussian railways . In: Brockhaus Konversations-Lexikon 1894-1896, Volume 13, pp. 426-432.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ There were factory, traffic, machine and workshop inspections (Klee, p. 179).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Prussian Railways . In: Brockhaus Konversations-Lexikon 1894-1896, Volume 13, pp. 427-432.

- ↑ Klee: Prussian Railway History, p. 126 ff

- ^ Itzenplitz, Heinrich Friedrich August, Count von . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 9, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Klee, p. 179.

- ↑ Klee, p. 179.

- ↑ a b Acta Borussica - Protocols of the Prussian State Ministry, bbaw.de (PDF; 2.8 MiB)

- ↑ Klee, p. 179.

- ↑ Klee, p. 179.

- ↑ Klee, p. 179.

- ↑ Eisenbahndirektion Mainz (ed.): Collection of the published Official Gazettes 7 (1903). Mainz 1904. Official Gazette of April 20, 1903. No. 22, p. 205.

- ↑ The relevant decree of Kaiser Wilhelm II. As King of Prussia, printed in: Eisenbahn-Directions Bezirk Mainz (ed.): Official Journal of the Royal Prussian and Grand Ducal Hessian Railway Directorate in Mainz of April 6, 1907, No. 18. Announcement No. 174, p. 203.

- ↑ Eisenbahndirektion Mainz (ed.): Official Journal of the Royal Prussian and Grand Ducal Hessian Railway Directorate in Mainz from March 29, 1913, No. 15. Announcement No. 182, p. 95.

- ↑ "acta Borussica", minutes of the Prussian State Ministry (PDF; 2.9 MiB)

- ^ Reichsgesetzblatt 1920, pp. 773 ff

- ^ Ingo Hütter, Oskar Pieper: Complete directory of German locomotives .

- ↑ Andreas Knipping: The express train. A German invention . In: Bahn-Extra , 6/2007: Der D-Zug, pp. 12–24, ISBN 978-3-89724-193-0