Kostrzyn nad Odrą

| Kostrzyn nad Odrą | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Poland | |

| Voivodeship : | Lebus | |

| Powiat : | Gorzów Wlkp. | |

| Area : | 46.17 km² | |

| Geographic location : | 52 ° 35 ' N , 14 ° 39' E | |

| Height : | 10 m npm | |

| Residents : | 17,778 (Jun. 30, 2019) |

|

| Postal code : | 66-470 and 66-471 | |

| Telephone code : | (+48) 95 | |

| License plate : | FGW | |

| Economy and Transport | ||

| Street : | DK 22 : Kostrzyn - Malbork - Grzechotki / Russia | |

| DK 31 : Szczecin - Słubice | ||

| Ext. 132 : Kostrzyn - Witnica - Gorzów Wielkopolski | ||

| Rail route : | PKP line 273: Wrocław – Szczecin | |

| PKP 203 and NEB 23: Tczew – Berlin | ||

| Next international airport : | Berlin Schoenefeld | |

| Szczecin-Goleniów | ||

| Gmina | ||

| Gminatype: | Borough | |

| Surface: | 46.17 km² | |

| Residents: | 17,778 (Jun. 30, 2019) |

|

| Population density : | 385 inhabitants / km² | |

| Community number ( GUS ): | 0801011 | |

| Administration (as of 2012) | ||

| Mayor : | Andrzej Kunt | |

| Address: | Graniczna 2 66-470 Kostrzyn n.O. |

|

| Website : | www.kostrzyn.pl | |

Kostrzyn nad Odrą [ ˈkɔstʃɨn nad ˈɔdrõ ] (German Küstrin , until 1928 written Cüstrin ) is a small town in the Polish Lubusz voivodeship .

Geographical location

The city is located in the Neumark , on the Warthe break in the western part of the Landsberger Niederung, at the confluence of the Warta into the Oder , around 80 km east of Berlin and around 90 kilometers south of Stettin .

Küstrin's urban area extended over both banks of the Oder until 1945. When, after the Second World War , German areas east of the Oder were placed under the administration of the People's Republic of Poland , the larger part of Küstrin east of the Oder came under Polish administration, while the smaller part west of the Oder (now the Küstrin-Kietz district of Brandenburg community Küstriner foreshore ) in Germany remained.

Districts

The actual old town , encompassed by the Brandenburg Fortress , was on the tongue of land between the Warta estuary and the Oder, which today belongs to Poland. Since the Second World War it has been a field of rubble, on which only individual buildings (Berliner Tor) have been reconstructed in recent years. The Kietzer Busch train station was located southeast of the fortifications.

The small district on the Küstriner Oderinsel, today Oderinsel Kietz, between the Oder mainstream in the east and the Oder floodplain in the west, also belonged to the old town. It remained German territory in 1945, but was used exclusively by the Soviet military as an artillery barracks until 1992 . The Küstrin-Altstadt train station was also located here.

To the west of the floodplain lay the village-like Lange Vorstadt, the Küstrin-Kietz with the Küstrin-Kietz train station, which remained on the German side after the Oder-Neisse border had been established , and further downstream, the likewise village-like Kuhbrückenvorstadt.

To the east of the mouth of the Warta, the Neustadt emerged in the 19th century , which grew rapidly as a result of the industrial settlement around the main station Küstrin-Neustadt and made up more than half of the built-up area of the city between the World Wars. Today it is the core area of the Polish city of Kostrzyn.

About 65% of the old Küstriner urban area from 1945 was placed under Polish administration after the end of World War II, the rest of the more rural suburbs west of the Oder remained with Germany.

history

View of the Prussian fortress town of Küstrin with the Brandenburg residential palace, Matthäus Merian , 1652

|

As early as the Bronze Age , Indo-European tribes settled individual sand islands in the Oderbruch. The area of today's Küstrin / Kostrzyn was inhabited by Teutons since the 2nd century BC and by Slavs after the migration in the 6th century .

In the 10th century the mouth of the Warta was on the border of the Polans and the Pomorans . Since Mieszko I , the Pomorans were repeatedly subjugated by the rulers of the emerging Poland and made tribute, but they were able to shake off Polish sovereignty again and again, cf. History of Pomerania . The Slavic word kosterin means a place where a lot of millet grows. The place Küstrin was originally located on an island in the corner between the Oder and Warthe. Here a rampart was built near a river crossing . In 1232, Duke Władysław Odon of Greater Poland , commissioned by Boleslaw V , entrusted this fortification to the Knights Templar at the site of the later Küstrin , with the instruction to build a forum (market) there under German law. Küstrin is mentioned for the first time in a document from 1232, with which Lorenz II. (1207-1233), Bishop of the Diocese of Lebus , to whose property the region belonged at the time, ceded the tithe from his latifundia to the Knights Templar forever.

In 1249 Kostrzyn became the seat of a Polish castellan . A service settlement ( Kietz ) on the opposite bank of the Oder (later Küstrin-Kietz ) belonged to the castle . In 1261 it was mentioned as a city. In the same year the Margraviate of Brandenburg came into being when the Ascanians incorporated the previously Polish state of Lebus as Neumark . Around 1300 Kostrzyn received from Albrecht III. of Brandenburg the Magdeburg town charter . In 1328 Emperor Ludwig is said to have given the town together with the towns and castles Falkenburg, Schievelbein, Neu-Wedel, Kallies, Reetz, Nörenberg, Hochzeit, Klein-Mellen and Berneuchen to the Lords of Wedel as a fief. The city coat of arms with the fish and the half Brandenburg eagle has been verifiable since 1364, first on a seal .

After a few changes of ownership, the city fell again to an order of knights at the beginning of the 15th century. This Teutonic Order of St. John had a bridge over the Oder and a castle ("Old House") built for the first time. In 1412 a pool of water in front of the building is mentioned. The city was threatened less from Poland than from Brandenburg when the ambitions of the Brandenburg Elector became known in 1425.

The territory of the Neumark was only bought in 1455 by Friedrich II of Brandenburg from the Teutonic Order . And it was not until 1517 that Albrecht von Brandenburg, the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, finally renounced the right of repurchase. There was a castle of the Teutonic Order here. Between 1440 and 1452, Cüstrin Castle was rebuilt by the Teutonic Order. This happens at a time when the Teutonic Order was in competition with the Electorate of Brandenburg and apparently feared an attack from the Kurmark. The previous castle "Altes Haus" at the Oder crossing will be demolished. The new "castle" (Ordensburg) has at least two towers and a "keep" near the drawbridge, two towers on the fence wall, "planks" to secure the old building and "a bulwark" on the castle wall (battlements). In 1447 the construction of a "Parcham" and the plan to build two more towers are reported. In 1452 "a large, strong, defensive tower" was completed. The order's plan to demolish the parish church in front of the castle fails because of the objection of the city of Küstrin. One can imagine the Teutonic Order Castle Küstrin as approximately square or rectangular with accentuated corners and with ditches, in the style of a fort castle .

In 1455 Küstrin became part of Brandenburg. In 1535 the city was raised to the seat of residence by Margrave Johann von Brandenburg-Küstrin (also known as Hans von Küstrin ). He had the place enlarged, redesigned and surrounded with fortifications. The castle was built and the city expanded into a fortress until 1568 . The first plan of the fortress was drawn up in 1535 by the engineer Maurer in the old Italian style with five bastions and cavaliers , but without a raveline . The construction of the earth walls lasted from 1537 to 1543. The brickwork took place from 1557 to 1568. The construction management took over from 1562 the Italian engineer Giromella . Margrave Johann von Brandenburg-Küstrin was unable to complete the extensive fortifications. The work on the wall was continued by Johann Georg and lasted until 1619.

After the death of the margrave in 1571, the city fell back to the Electorate of Brandenburg. Since then, the city had until the 20th century a permanent Brandenburg and Prussian or German garrison , interrupted only by the French occupation from 1806 to 1814. The garrison shaped the city since 1641 as the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm , the Brandenburg-Prussian army to life called. In the years from 1640 to 1688, thanks to the garrison and its location, Küstrin was developed into one of the strongest fortresses in the German states.

Since 1580 Küstrin was the capital of Neumark . At the time of the Kingdom of Prussia , after the Congress of Vienna in 1816, the districts of Cüstrin and Königsberg in the administrative district of Frankfurt (Oder) in the province of Brandenburg . The district offices were in Küstrin and in Königsberg. On January 1, 1836, the district in Küstrin was dissolved and added to the Königsberg district.

Küstrin experienced an upswing in 1857 when it was connected to the railway line of the Prussian Eastern Railway , which crossed the Oder northwest of the fortress . The city expanded to the east of the fortress / old town around the new town and, because of the converging road, rail and waterways, developed into an important traffic junction, including on the important Reichsstraße 1 ( Aachen - Berlin - Küstrin - Königsberg ). Today this road ends as Bundesstraße 1 behind Küstrin-Kietz on the German-Polish border, but continues on the Polish side ( Droga krajowa 22 , Droga krajowa 31 and Droga wojewódzka 132 ) in the direction of Gorzów Wielkopolski .

After the First World War , most of the military installations were dismantled. In 1923 there was an unsuccessful Küstriner putsch in the garrison town , with which paramilitary reactionary forces wanted to take action against the policies of the then government. In the course of the rearmament of the German Reich , numerous military buildings were rebuilt after 1933. In addition, a pulp factory and the Germany settlement were built in the Kietz district. In 1939 Küstrin still had 24,000 inhabitants.

Towards the end of the Second World War , the Red Army managed to break through from the Vistula to the Oder in the spring of 1945 . During the final phase of the war, Küstrin was declared a fortress on January 25, 1945 and the population was evacuated from the eastern districts on February 19, 1945. In the battles for Küstrin from mid to late March 1945, 90 percent of the old town was destroyed, and Küstrin was next to Glogau the most heavily destroyed town in eastern Germany. On April 16, 1945, the Russian bridgehead at Küstrin became the most important point of departure for the Soviet army's offensive on Berlin .

At the end of the war, Küstrin was in Soviet hands. According to the Potsdam Agreement , the areas east of the Oder and Lusatian Neisse were placed under Polish administration. The immigration of Polish civilians began in Küstrin. The settlement with Poles was relatively slow here, the influx of the closed city was limited to railway workers and customs officers. In 1946 there were 634 Polish residents. The city was renamed Kostrzyn (since 2003 Kostrzyn nad Odrą ). At the time, the remaining inhabitants, around 1,500 Germans, lived in the settlements on the northern outskirts. This German population was expelled in the period that followed .

The rubble of the heavily destroyed old town was completely cleared away after the war. It was not until 1954 that the Neustadt was rebuilt and expanded in connection with the construction of the pulp and paper mill. In 1992, the rail and road crossing over the Oder were reopened. In 1994 the Kostrzyn-Słubice Special Economic Zone was set up, which resulted in a further increase in population.

Fortress Küstrin (old town)

The Prussian fortress ruins and former old town are located on a peninsula at the confluence of the Oder (Odra) and Warta (Warta) rivers. Küstrin u. a. by the execution of Hans Hermann von Kattes , a childhood friend of Friedrich II , after his attempt to escape.

At first Küstrin belonged to the Electorate of Brandenburg . In the course of the division of territory among the sons of Elector Joachim I Nestor of Brandenburg, the Neumark with Küstrin and other areas as the Margraviate Brandenburg-Küstrin fell to his younger son Johann.

From 1536 onwards, because of its strategic location, Margrave Johann von Brandenburg-Küstrin , brother of Elector Joachim II Hector of Brandenburg, raised it to the status of a residence and expanded it into a fortress. Since the fortress was built at the confluence of the Oder and Warta rivers, the rivers formed a natural protection on two sides. In addition, the marshy meadows on the eastern land side made Küstrin a fortress that was difficult to conquer. The construction of the stone fortress lasted until 1557 and cost Brandenburg the then horrific sum of around 160,000 guilders . After the death of Margrave Johann in 1571, the Margraviate Brandenburg-Küstrin fell back to the Electorate of Brandenburg.

The Küstriner fortress was built on the Italian model in the years 1537–1543 and 1563–1568 and was completed in the 17th century. The fortress was shaped like an elongated hexagon. In the southwest the fortress borders the Oder. In addition to the fortress walls, the fortifications also included the bastions of King , Queen , Crown Prince , Crown Princess , Philip and Brandenburg . The bastions were connected by walls and surrounded by a moat. The fortress also includes three Ravelins Albrecht , Christian-Ludwig and August-Wilhelm . Three gates led into the city: the Berliner Tor in the northern part of the city, the Zorndorfer Tor in the eastern part and the Kietzer Tor in the southern part. Inside the fortress was the city with the market square, churches, castle and all military facilities (e.g. hospital , magazines and gun foundry). The soldiers of the fortress garrison were initially billeted in private households.

The most famous buildings include:

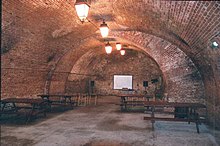

- The Küstrin Castle was the most important part of the Küstrin fortress; it was built as a castle by the crusaders . After the great fire in 1758, which almost destroyed the entire castle, it was rebuilt. In 1814 the castle was converted into a barracks . Only the partially filled basement rooms have been preserved. After the Hitler assassination attempt in 1944 until shortly before the end of the war in 1945, alleged co-conspirators - to whom nothing could be proven - were imprisoned in Küstrin Castle

- The Marienkirche was built in 1396 and rebuilt in the 16th and second half of the 18th century. Today only the outlines of the church wall, the floor and parts of the tombs are preserved.

- The two-story town hall was built from 1572 to 1577 on the market square in the Renaissance style. Only the outlines and foundations have been preserved.

From 1627 to 1633, the Brandenburg Elector Prince and later Elector Friedrich Wilhelm (1620–1688) stayed in the fortress. In his reign from 1640 to 1688 he had Küstrin expanded into one of the strongest fortresses in Germany . The Küstrin fortress, considered impregnable, played no military role in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648).

After his attempt to escape from Prussia , the Prussian Crown Prince Friedrich , who was born in 1712, was imprisoned by his father Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia from 1730 to 1732 in Küstriner Castle. On November 6, 1730, the king had his friend and escape helper Hans Hermann von Katte beheaded on the Brandenburg bastion in front of the crown prince .

During the Seven Years' War , Küstrin was besieged by Russian troops from August 15 to 18, 1758 and set on fire. Because it was still mostly made of wood, it burned down completely, but the fortress could not be conquered. King Friedrich II shocked the fortress and defeated the Russians on August 25, 1758 east of Küstrin in the battle of Zorndorf . After the Prussian defeat by Napoleon in 1806 , the Küstrin fortress was used by the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III. of Prussia and his wife Queen Luise as a refuge for a short time. After the royal couple had moved on to Memel , Colonel Ingersleben handed the fortress over to the French on November 1, 1806 after a few minor skirmishes with French advance detachments . It was not until March 20, 1814, after a year-long siege by Russians and Prussians, that the French surrendered , and Prussia took over the fortress again. In 1819 the gymnastics father Friedrich Ludwig Jahn was imprisoned in the fortress. The first infantry barracks were built in 1876 . With the invention and introduction of explosive projectiles , brick fortresses were suddenly devalued and lost their military importance; you could "shoot them together".

In 1901 and 1902 the fortifications in front of the Küstriner Castle were removed. Küstrin remained an important garrison town . In 1913 a third unit was stationed here. The troops were housed in barracks in the fortress and on the Oder Island.

After the First World War, according to the provisions of the Versailles Treaty, parts of the Küstrin Fortress had to be razed by the German Empire . From 1921 to 1931 all fortifications on the north and east sides were demolished (bastions Queen, Crown Prince and Crown Princess with the fortress wall in between and the Zorndorfer Tor as well as the Christian-Ludwig Ravelin). The trenches in this area were also filled in and a new bypass road was created around the old town. On the Oder side, the fortress wall between the bastions of König and Brandenburg was torn down and a park was created here, which was called the Kattewall.

Küstrin also lost its importance as a garrison due to the personnel restriction of the Reichswehr ; only a few units remained in Küstrin. Only with the armament of the Wehrmacht during National Socialism were units again stationed in Küstrin; In 1939 the troop strength of the imperial era was again reached and exceeded. Küstrin was declared a fortress by Adolf Hitler in January 1945 (see Fester Platz (Wehrmacht) ) and held against the numerically superior Red Army until the end of March 1945 . The old town was largely destroyed during the fighting.

On April 26, 1945 - immediately before the shooting, which was planned by Himmler's personal order - a group of prominent prisoners escaped and went into hiding with the help of the commandant of the fortress detention center (Major Dr. Leussing) and a religious. Among them were Lieutenant General a. D. Theodor Groppe , the commander of the Dutch army General Willem Röell (1873-1958) and Lieutenant General Hans Speidel (1897-1984).

In the first years after the war under Polish administration, the ruins of the old town, especially the bricks from the ruins, were largely removed and used for the reconstruction of Warsaw until 1956; the rest were finally razed to the ground in 1967. Reconstruction did not take place; the area is now an uninhabited desert .

After the area had been in the border area closed to the public for decades and was therefore out of the way, streets and building remains were exposed in the 1990s after the fall of the Iron Curtain . Apart from the streets with pavement sections, curbs and granite pavement slabs, only the entrances, foundation walls and remains of foundations are visible of the building. Remnants of the castle and parish church are still recognizable. Sometimes the rails for the city tram , which came from Neustadt to the Berliner Tor, were still visible in the pavement.

Parts of the former fortifications have been preserved today (e.g. the bastions König , Königin , Brandenburg and Philipp and the fortified Berliner Tor and Kietzer Tor). The Kietzer Tor and the Phillip Bastion including its casemate (it houses the Museum of the History of Küstrin) have now been restored. The Berliner Tor has also been expertly restored.

After 1945, the Soviet Union erected a memorial for fallen Soviet soldiers on the König Bastion (according to plans by Lev Kerbel ). The obelisk , which stands on a raised foundation, is flanked by a gun and crowned with a Soviet star, was dismantled in November 2008, the gun removed in April 2009. After the war, a Soviet military cemetery was laid out around the memorial on the König Bastion .

The old town of Küstriner is now also known as "Pompeii on the Oder". On the site of the former fortress walls and bastions in the east of the old town (which were dismantled in the 1920s), the Hotel Bastion, a gas station (whose design is intended to be reminiscent of the Zorndorfer Tor) and a longer building block were built. In 2009, street signs and signs on prominent former buildings (e.g. at the castle, at St. Mary's Church) were put up in Polish and German to provide information about the respective building. These panels are supplemented with a picture of the building before it was destroyed. A tourist information office has now been set up in the Berliner Tor, offering, among other things, short guides including a city map. Some finds from the area also give an insight into the eventful history of Küstrin. The old town is now part of the European Citadel Route .

In the area between the Oder and the Oder-Vorflut-Kanal (so-called "Oderinsel", military restricted area from 1945 to 1991 ), which belonged to the old town until 1945 and today to Küstrin-Kietz, there is a former artillery barracks of the Wehrmacht , which after the end of the Second During the Second World War it was occupied by the Soviet armed forces ( Red Army ) until it withdrew in 1991 and is empty today. The Küstrin-Altstadt station located here on the line between Küstrin-Kietz and Kostrzyn nad Odrą is no longer in operation.

The Küstrin Fortress also included four outer forts:

- Fort Gorgast in Gorgast

- Fort Zorndorf in Zorndorf

- Fort Chernov in Chernov

- Fort Säpzig in Säpzig

In addition to the forts, four lunettes (A to D) were erected in the western area of the fortress ; they are still partially preserved.

Küstrin-Neustadt

In 1857 Küstrin was connected to the railway network of the Prussian Eastern Railway . Thanks to this connection to the railway, in addition to the water connection of the Oder and Warthe and to Reichsstraße 1 , Küstrin developed into an important traffic junction, which was its undoing at the end of the Second World War. Since the city was developing very quickly at this time and the walled-in old town could no longer grow, the district of Küstrin-Neustadt was founded.

This former district of Küstrin-Neustadt , northeast of the Warta , today forms the center of the town of Kostrzyn nad Odrą .

Until 1907 it was known as a short suburb . After receiving a direct rail link with Berlin in 1867 (a two-story train station that still exists today), the suburb experienced an economic boom. The Küstriner industry was known for the manufacture of potato flour , machines (mainly steam engines) such as the machine works and iron foundries of Adolf Wagener (later Kümeis and then Oderhütte and Franck & Co.), Gustav Ewald, H. Eisenach (also copper and brass goods) and Hermann Schmidt, steam saw mills and steam cutting mills, pianofortes , fire extinguishers, roofing felt like the factories of Minuth and Veit, asphalt, brick kilns and breweries like those of Felix Graul and Marx Hermann.

Not much of the Neustadt has survived either, apart from the train station, the water tower, the girls' school and the Wagenerische Villa on Rackelmannstrasse, today Kopernika 1, a house that has a symbolic meaning for many former Küstriner, a reminder of the city and life from then.

Demographics

In the period between the Reformation and the end of the Second World War , the population of Küstrin was predominantly Protestant. The proportion of the population of Catholics was under ten percent.

| year | Residents | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1750 | 4675 | |

| 1800 | 4934 | an additional 1200 garrison members. |

| 1852 | 7445 | an additional 1387 garrison members. |

| 1867 | 10,013 | on December 3rd |

| 1871 | 10.141 | on December 1st, of which 9593 Protestants, 346 Catholics, 28 other Christians, 174 Jews |

| 1875 | 11,227 | |

| 1880 | 14,069 | |

| 1890 | 16,672 | including 1,296 Catholics and 184 Jews |

| 1895 | 17,552 | (9,910 males, 7,642 females), including 1,428 Catholics and 159 Jews. |

| 1900 | 16,473 | including the garrison (a 48th infantry regiment and a 54th field artillery division ), of which 1,095 were Catholics and 143 Jews. |

| 1925 | 19,383 | of these 17,806 Protestants, 1,181 Catholics, 39 other Christians and 141 Jews. |

| 1933 | 21,270 | including 19,537 Evangelicals, 1,307 Catholics, two other Christians and 96 Jews |

| 1939 | 21,499 | thereof 19,333 Evangelicals, 1,343 Catholics, 191 other Christians and 20 Jews |

| year | Residents | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | approx. 11,000 | |

| 2007 | around 20,000 |

economy

General

Due to Küstrin's military function, the majority of the population was employed in the service industry, brewing industry and in agricultural production to feed the fortress garrison until 1809 . There was little trading activity. The first factories were built at the beginning of the 19th century, the rivers were regulated, which enabled Küstrin to develop economically and spatially. 1885 there were potato flour, machinery, copper and Messingwaren-, cigar, Öfen-, rayon and cellulose , brush and brush factory and two steam saw-mills, a machine shop, a Holzimprägnieranstalt, five breweries, brickworks, and shipping. Telephone traffic was introduced in 1892, and in 1913 the city received electricity. The construction of the main train station in Neustadt and the expansion of the railway network into an important transport hub drove the city's development into an industrial center. In 1939 there were 32 larger companies. Well known were the Rütgers-Werke, which made railway sleepers from wood, the North German potato flour factory and the old paper and cellulose factory (Zellwolle und Zellulose AG). However, the economic development was interrupted by the Second World War.

With the reconstruction of Küstrin, a large industrial area developed north of the Warta. In 1997 the Kostrzyn-Słubice Special Economic Zone was founded, in which several companies settled within a short period of time. Over 1000 jobs were created in the city. Complexes 2 and 3 were formed in Kostrzyn as part of the network of special economic zones. The latter houses the same area as in the 19th century north of the Warta and along Landsberger Strasse (today Gorozowa). The main industries are wood, paper, food, machinery, plastics, textiles, construction and automobiles.

Industry

In 1958 the cellulose and paper mill was reopened as Kostrzyńskie Zakłady Celulozowo-Papiernicze . This factory was built by the Phrix Works in the 1930s . In the 1940s it was one of the most successful companies in Küstrin. In 1993 it was sold to the Swedish Trebruk Group and has been operating as Arctic Paper Kostrzyn SA since 2003

traffic

Road traffic

Kostrzyn is located on the Polish DK 31 ( Droga krajowa 31 , literally "Landesstraße" / analogously "Nationalstraße" 31) from Stettin (Szczecin) to Słubice and on DK 22 .

At the end of the 20th century, DK 22 ran from the Oder to the Vistula just like the former Reichsstraße 1 , which is today Bundesstraße 1 in Germany. In the meantime, on the western 30 kilometers, it has become the first part of the straight line Kostrzyn – Posen (Poznań ), 1932/39 to 1945 Reichsstrasse 114 . Only from Gorzów Wielkopolski (Landsberg (Warthe)) does the DK 22 still have the old route.

As DK 31 extends south via Górzyca (Göritz) to Słubice, the former Frankfurt Dammvorstadt, the national road status of the former Reichsstraße 112 (Forst – Altdamm (Szczecin- Dąbie )) between Kostrzyn and Frankfurt through the Oder border has been doubled, as today's B 112 , until 1990 F 112, continues to connect Küstrin-Kietz with Forst.

Rail transport

In October 1857 the Prussian Eastern Railway opened its connection from Frankfurt (Oder) via Küstrin and Landsberg (Warthe) to Kreuz on the Stettin – Posen line . The line from Kreuz via Dirschau (Polish: Tczew) to Danzig had existed since 1852 and since September 1857 the Vistula Bridge near Dirschau established a connection to the Marienburg - Königsberg - Eydtkuhnen line , which was completed in 1852/53 . This created a direct connection from Berlin to East Prussia. With the opening of the line from Berlin via Strausberg to Küstrin in 1867, the distance to East Prussia was shortened and the connection via Frankfurt (Oder) became less important. In 1875, Küstrin was reached from the south by the Breslau – Stettin railway line , which two years later was passable for its entire length. The tower station Küstrin-Neustadt, today's Kostrzyn station, was built at the intersection with the Eastern Railway . The direct route west of the Oder between Frankfurt and Küstrin was shut down in 2000 and has now largely been dismantled.

Since the city has belonged to Poland, the north-south traffic between the port city of Stettin and Wroclaw in Silesia on the Wrocław – Szczecin railway has dominated. Despite the restoration of the Oder bridges in 1947, regular public passenger traffic over the Oder was suspended until 1992. After the Oder crossing was reopened, trains ran from Berlin to Gorzów Wielkopolski (Landsberg / Warthe in German) at times . At the moment there are no continuous passenger trains on the old Ostbahn line, the hourly regional trains of Niederbarnimer Eisenbahn AG (NEB) from Berlin-Lichtenberg station end in Kostrzyn, as do the PKP trains from Gorzów. The tariff of the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg is valid up to Kostrzyn train station. In addition to the main lines, there is also a railway line via Myślibórz (Soldin) in the direction of Choszczno (Arnswalde), which however no longer has any passenger traffic.

tram

The Küstrin tram began in 1903 as a horse-drawn tram, which was in operation until 1923. Its two lines ran between the Küstrin Altstadt train station on the Oder Island, which still belongs to Germany but is no longer inhabited, via the main river of the Oder and the actual old town to the Küstrin-Neustadt train station and from there to the Stadtwald and between the market square in the old town and the infantry barracks in the new town.

From 1925 to 1945 an electric tram operated between the old town and the new town. There were three tram lines:

- Line 1: Bahnhof Altstadt <> Markt <> Stern <> Bahnhof Neustadt

- Line 2: Stern <> Landsberger Straße <> Tax Office

- Line 3: Stern <> Zorndorfer Straße <> Stadtwald

Twin cities

- Küstriner Vorland (Germany)

- Peitz (Germany)

- Sambir (Ukraine)

- Seelow (Germany)

- Tomelilla (Sweden)

- Woudrichem (Netherlands)

Culture and sights

Buildings old town

- Berlin Gate

- Kietzer Gate

- Bastion King

- Bastion queen

- Brandenburg Bastion

- Bastion Philipp, casemates with an informative and attractively designed museum on the prehistory of the area and the history of Küstrin up to the post-war period.

- Monument plinth of Johann von Brandenburg, also called Hans von Küstrin, which was erected on the remains of the former foundation.

Buildings Neustadt

- Railway station from the 19th century, built 1872–1874, with tracks on two levels, with interesting architecture and technical features.

- Water tower 1903, now out of service.

- “The Lion” - memorial at the former Moltkeplatz for the Küstriner who fell in World War I.

- Kulturamt - formerly Prussian calibration office.

- Villa Wagener - the only surviving residential building in the former Rackelmanstrasse, today Kopernika 1.

Parks

- Warta Estuary National Park - The park was created in place of the Słońsk Nature Reserve, which has existed since 1977, and is a unique place to stay for water and mud birds. About 240 species of birds live here.

Events

Every year on the last weekend in August, the Kostrzyner Fortress Days take place, partly as a reminder of the completely destroyed residential areas, the destroyed castle and above all the forts, lunettes and inter-field buildings in the old town. There are exhibitions, seminars, parades, concerts, theater performances, artillery battles, knight fights, as well as bike tours, bus and car trips in the area. You can also visit the book market, antique market and food stalls and watch traditional craftsmen such as blacksmiths, potters, shoemakers and amber cutters. In 2010, the tenth anniversary was celebrated on September 12th and 13th. This time there was a historical parade from Kostrzyn's city center to the old town, an opportunity to experience Kostrzyn's history up close.

Since 2002, the World Hiking Days have also taken place in mid-May, partly through the Warta Estuary National Park. Participants can choose between 12, 25 and 45 km route lengths.

Since 2004 the Pol'and'Rock Festival has been taking place on a former military site in the immediate vicinity of the city (until 2017 stop Woodstock / Przystanek Woodstock ). Entry and camping are free. In 2010 there were 250,000 to 300,000 visitors.

Personalities associated with the city

sons and daughters of the town

- Katharina von Brandenburg-Küstrin (1549–1602), daughter of Margrave Johann von Küstrin

- Caspar von Barth (1587–1658), German philologist and private scholar of the Baroque period

- Johann Fromhold (1602–1653), German statesman and diplomat

- Christian Albrecht von Dohna (1621–1677), general from Brandenburg

- Moritz von der Pfalz (1621–1652), Prince of the Palatinate , Vice Admiral in English service, most recently a pirate leader

- Friedrich von Dohna (1621-1688), officer, governor of the Principality of Orange

- Wilhelm von Brandt (1644–1701), Lieutenant General in Brandenburg and Prussia

- Philipp Sigismund Stosch (1656–1724), personal physician from the Elector of Brandenburg, doctor and councilor in Küstrin, member of the “ Leopoldina ” academy of scholars

- Johann Ernst Schaper (1668–1721), German physician and Mecklenburg politician

- Karl Friedrich Necker (1686–1762), Professor of Law in Geneva

- Philipp von Stosch (1691–1757), art collector and diplomat

- Ludwig Lebrecht Koppin (1766–?), Deichhauptmann (1830–1840) of the Oderbruch ("Koppin'sche Karte")

- Georg Wilhelm von Lüdemann (1796–1863), Prussian district administrator and police director as well as travel writer

- Johann Ferdinand Heyfelder (1798–1869), German surgeon and university professor

- Johann Heinrich Ludwig Maresch (1801–1864), Prussian major general

- Emil Flaminius (1807–1893), architect, Prussian construction clerk

- Leo von der Osten-Sacken (1811–1895), Lieutenant General

- Albert Ferdinand Heinrich Berndt (1820–1879), German lawyer and member of the Prussian House of Representatives

- Georg Heinrich Fritze (1826–1878), founder of the Küstriner metal industry

- Adolf Ferdinand Gustaph Wagener (1835–1894), founder of one of the leading factories for agricultural machinery

- Gustav Robert Ewald (1837–1892), founder of a factory for fire extinguishers

- Alfred von Tirpitz (1849–1930), Grand Admiral of the Imperial German Navy and State Secretary of the Reichsmarineamt

- Curt von Maltzahn (1849–1930), German naval officer, naval war strategist and military historian; Opponent of his friend Tirpitz

- Anna von Blomberg (1858–1907), German writer

- Karl Wendt (1874–?), 1925–1928 Chairman of the Association of German Engineers (VDI)

- Leopold Petri (1876–1963), lawyer, judge and police chief in Bremen

- Fedor von Bock (1880–1945), German field marshal of the Wehrmacht

- Mara Heinze-Hoferichter (1887–1958), German writer

- Fritz Adam (1889–1945), SA chief and politician (NSDAP)

- Gustav Ewald (1895–1983), fire extinguishing equipment manufacturer, Colonel in the Air Force and technology historian

- Paul Vollrath (1899–1965), German politician (NSDAP)

- Alfred Driemel (1907–1947), German National Socialist and SS-Obersturmführer in concentration camps

- Erich Linnhoff (1914–2006), German athlete, 400 m runner and 4 × 400 m relay

- Inge Fuhrmann (* 1936), German sprinter

- Jörn Müller (* 1936), German chemist

- Ursula Koch (* 1938), German historian and curator

- Peter Jahn (* 1941), German historian

- Astrid Philippsen (* 1942), German translator

- Bernd Weinkauf (* 1943), German writer

- Edward Pasewicz (* 1971), Polish author and composer

- Dariusz Dudka (* 1983), Polish national football player (Levante UD)

- Dawid Kucharski (* 1984), Polish national football player (Heart of Midlothian FC)

- Grzegorz Wojtkowiak (* 1984), Polish national football player (Lechia Gdańsk)

- Łukasz Fabiański (* 1985), Polish national football player (goalkeeper - Swansea City)

Fixed

- 1707–1709 Domenico Manuel Caetano (around 1670–1709), alchemist

literature

Current monographs

- Peter Carstens: In the ruins of Küstrin . On the Oder you can visit the remains of a small German town ..... in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung from November 12, 2017, Frankfurt am Main, No. 45, under: "Politics" p. 5

- Peter Westrup: Is nature cruel or merciful? Küstrin was a splendid fortified town .... In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, August 20, 2015, No. 192, page R 5 (with images)

- Frank Lammers: Küstrin. City history and city traffic. Verlag GVE, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-89218-091-1 .

- Küstrin in old views. Volume 1. 2nd revised edition. Verlag Verein für die Geschichte Küstrin, Küstrin-Kietz 2004, ISBN 3-935739-02-8 .

- Küstrin in old views. Volume 2. Verlag Verein für die Geschichte Küstrin, Küstrin-Kietz 1998, ISBN 3-00-002637-1 .

- Rudolf Kunstmann: Küstrin - The city on the Oder and Warthe 1232–1982. Wilhelm Möller, Berlin 1982

Older representations, sources

- Friedrich Wilhelm August Bratring : Statistical-topographical description of the entire Mark Brandenburg . Volume 3, Berlin 1809, pp. 93-97 .

- W. Riehl and J. Scheu (eds.): Berlin and the Mark Brandenburg with the Margraviate Nieder-Lausitz in their history and in their present existence . Berlin 1861, pp. 405-411.

- Heinrich Berghaus : Land book of the Mark Brandenburg and the Margraviate Nieder-Lausitz in the middle of the 19th century. Volume 3. Printed by and published by Adolph Müller, Brandenburg 1856, pp. 392–399 .

- KW Kutschbach: Chronicle of the city of Küstrin. Enslin, Küstrin 1849 ( full text ).

- Siegmund Wilhelm Wohlbrück: History of the former diocese of Lebus and the country of this name. Volume 1. Self-published, Berlin 1829, pp. 433-438 ( full text ).

- JC Seyffert: Annals of the city and fortress Küstrin from documents and manuscripts. Trowitzsch, Küstrin 1801 ( full text ).

- Siegismund Justus Ehrhardt : Old and new Küstrin, or additions to a historical message about the fate of the main = city and fortress Küstrin in the Neumarck. Christian Friedrich Günther, Glogau 1769 ( full text ).

- Freiherr von Zedlitz : The state forces of the Prussian monarchy under Friedrich Wilhelm III. Volume 3: The military state. Maurersche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1830, p. 197f.

- Fredrich, C .: The city of Küstrin. Küstrin: Carl Adler, 1913.

Lexical notations

- Küstrin , encyclopedia entry, in: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition. Vienna and Leipzig 1908, Volume 11, p. 890 ( Zeno.org ).

Web links

City maps

- current plan of Kostrzyn

- Küstrin 1930, reprinted by Pharus-Verlag

- Historical city map from around 1938

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b population. Size and Structure by Territorial Division. As of June 30, 2019. Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS) (PDF files; 0.99 MiB), accessed December 24, 2019 .

- ^ Oderinsel Kietz ( Memento from October 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ A b Brockhaus Enzyklopädie, FA Brockhaus Wiesbaden, 17th completely revised edition, tenth volume

- ^ Heinrich Berghaus : Land book of the Mark Brandenburg and the Markgraftum Niederlausitz in the 19th century . Volume 3, Brandenburg 1856, p. 397.

- ^ Siegmund Wilhelm Wohlbrück : History of the former diocese of Lebus and the country of this name . Volume 1, Berlin 1829, p. 647.

- ↑ Ulrich Schütte: "The castle as a defense system", article: "The castle in Küstrin", p. 131, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft Darmstadt, 1994

- ↑ Rozporządzenie Ministra Spraw Wewnętrznych i Administracji, December 17, 2002, Dz.U. 2002, No. 233, poz. 1964. Online ( Memento of the original from September 10, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ RBB report "Küstrin - Pompeji on the Oder", May 8, 2018

- ↑ a b Peter Westrup: Is nature cruel or merciful? Küstrin was a splendid fortress town until it sank into smoking ruins in the spring of 1945. Today its ruins lie like a forgotten Pompeii under grass and underbrush . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, August 20, 2015, p. R5.

- ↑ a b c Berghaus (1856), ibid, p. 393.

- ↑ a b Royal Statistical Bureau: The communities and manor districts of the Prussian state and their population . Part II: Province of Brandenburg , Berlin 1873, pp. 118-119, No. 4 ( online ).

- ^ A b c d e Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. Province of Brandenburg, district of Königsberg / Neumark. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- ^ Cüstrin . In: Brockhaus Konversations-Lexikon 1894–1896, Volume 4, p. 643.

- ^ Meyer's Large Conversational Lexicon . 6th edition. Vienna and Leipzig 1908, Volume 11, p. 890 ( Zeno.org ).

- ↑ a b Meyer's Encyclopedic Lexicon . 9th edition. Volume 14, Mannheim / Vienna / Zurich 1975, p. 511.