History of Pomerania

Pomerania is a region on the southern Baltic coast between the Mecklenburg Lake District in the west and the Vistula in the east with a long history. The part west of the Oder is called Western Pomerania and today belongs (except for the area around Stettin ) to the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania . Eastern Pomerania , east of the Oder , - like the region around Stettin and the other areas east of the Oder-Neisse border - became a part of Poland in the wake of the Second World War .

The name Pomerania is of Slavic origin: po more - (land) "by the sea" .

Early days and Teutons

The area of today's Pomerania has been settled since the Stone Age. In the 8th to 6th centuries BC, carriers of the Lausitz culture extended their settlement area along the Oder to the Baltic Sea coast. Western Pomerania has been part of the Germanic Jastorf culture since the 5th century . Ancient authors around the turn of an era call this the Rugier . In the 7th century BC the Pomeranian face urn culture arose west of the mouth of the Vistula . This culture later expanded over much of what is now Poland. Which were mentioned by name as a Germanic speaking people Bastarni , but only when they settled in the last century before the Christian era in the eastern Danube region. The Goths immigrated to the Vistula region from around 100 BC . Their traces, the Wielbark culture , show a mixed culture of Nordic and other elements. The Goths began to migrate to the southeast as early as 200 AD. During the migration , almost all Germanic tribes left the country south of the Baltic Sea by the middle of the 5th century.

Slavic settlement

After the Goths had moved further south from 200 AD, the Rugians soon followed. From around 500 AD, Slavs , coming in two main phases from the southwest, settled the largely uninhabited areas. Only in a few places on Rügen, near the Stettiner Haff and on the coast near Danzig, is there evidence of settlement continuity from the Germanic to Slavic times. Remaining Germanic parts of the population may have assimilated to the Slavs or - on the coast - maintained their connections to Scandinavia ( Jomswikinger ).

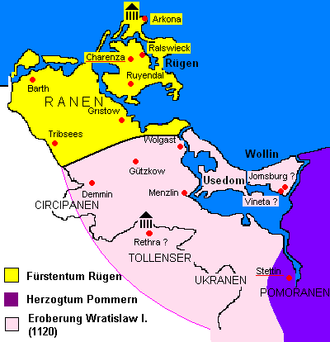

The different tribes of the Slavs were often named after their settlement area. To the west of the Oder , these were the Zirzipans and Tollensians who, along with other tribes, were assigned to the Wilzen and later the Liutizen . The R (uj) anen (around and on Rügen ) and the Wolliners (around Wollin ) lived on the islands . The name of the Rujanen as well as the island of Rügen probably goes back directly to the assimilated Rugians. Slavs who settled east of the Oder were called Pomorans (= "by the sea", in contrast to the inland "Polans" who settled in the south). There were castles (e.g. Demmin , Stettin , Kolberg ), Wendish-Scandinavian trading centers ( Ralswiek , Menzlin , Vineta ) and sanctuaries ( Jaromarsburg ). In addition to agriculture, cattle breeding and beekeeping, these Baltic turns also operated seafaring. They were not only fishermen, but also traders. Similar to what was common in Scandinavia at the time, some of these seafarers also worked as pirates.

From the 10th century, the Slavs of what would later become Pomerania came under the influence of their neighbors. Strong, feudal, Christian powers with expansive interests arose around the small, pagan Wendish tribes: they were threatened by the German rulers of the Holy Roman Empire from the west, the Danes from the north and the Polish Piasts from the southeast .

Unstable power relations

Otto I, King of Eastern Franconia, established the Billunger Mark in 936 and the Saxon East Mark (later the North Mark ) to the south of it . In 955, after the victory of the allied Saxons and Slavic Rans over the Obodrites in the Battle of the Raxa (Recknitz) , these brands were extended to parts of Pomerania. Due to the great Slav uprising (983) of the Liutizen alliance, large parts of the Slav area east of the Elbe became independent again. The Billunger's mark was given up entirely. The main place of the Liutitzen was the temple of Rethra on Lake Tollense . The alliance disintegrated relatively quickly, but the Obodrites built up a kingdom for several decades which, in addition to today's Mecklenburg, also included large parts of Brandenburg.

The Polish Duke Bolesław I the Brave founded in 1000 in agreement with Emperor Otto III. a missionary diocese in Kolberg . However, around 1010 the pagan Pomorans forced Bishop Reinbern, who was appointed there, to flee, which ended the short history of the Kolberg diocese. When a pagan reaction triggered a state crisis in Poland around 1035, the Pomorans made themselves politically independent through an uprising. After the end of the crisis around 1040, the Piasts restored their sovereignty over the Pomorans and thus their obligation to pay tribute in 1042.

The first prince of the Pomorans mentioned by name in the annals is Duke Zemuzil, mentioned in 1046 . In 1046 the German King Heinrich III invited . the dukes Casimir I the innovator of Poland, Břetislav I of Bohemia and Zemuzil of Pomerania to conclude a peace settlement in Merseburg .

In the winter of 1068/69 the main Lutheran shrine, Rethra, was destroyed by German troops, whose function as the religious center of the pagan Western Slavs was taken over by the Ruegan Jaromarsburg on Cape Arkona . In 1091 Szczecin was conquered by Władysław I Herman , Duke of Poland. However, the Pomorans always tried to remain as independent as possible.

Rügen and the adjoining mainland as far as the Ryk and Reckitz rivers were not part of Pomerania at the time, but the independent principality of the Ranen. For a long time it competed with the Danish kings for supremacy in the western Baltic Sea. Then conquered in 1168 King Valdemar I of Denmark , the Principality of Rügen , which submitted ranischen complaints princes of his suzerainty and let Christianize the area. The princes of Rügen remained fiefs of the Danish kings until the dynasty died out in 1325.

Development of the Christian duchy

The Polish Duke Bolesław III. Schiefmund subjugated the area around the Oder estuary and Western Pomerania with the main castles of Cammin and Stettin in three campaigns in 1116, 1119, 1121. It is disputed whether Duke Wartislaw I of Pomerania had to submit to him after the capture of Stettin in 1121 or was appointed by him has been. Duke Wartislaw I made tribute payments and promised Christianization. He is the first known Pomerania Duke from the dynasty of grasping that until their extinction in 1637 ruled Pomerania.

Bolesław had an interest in Christianizing the newly conquered Pomerania. The missionary trip he supported by a bishop Bernhard 1121/1122 from Spain was unsuccessful. At Bolesław's instigation, Bishop Otto von Bamberg undertook his first missionary trip to Pomerania in 1124/1125 , which was already very successful. It concerned the area under the rule of Wartislaw I between the Oder and Persante or the Gollenberg , that is, western Pomerania . Probably at the same time, Wartislaw I, possibly with Polish help, subjugated the Lutizian settlement areas west of the Oder to Güstrow and Müritz . The Ranenreich between Ryck and Recknitz with the island of Rügen remained independent .

In 1128 Otto von Bamberg, this time supported by the emperor and German prince, undertook his second missionary trip, which took him to the Lutizian settlement area west of the Oder. In the presence of Wartislaw I, the greats of the country, including the castellans von Demmin and Wolgast , accepted Christianity at Whitsun 1128 at a meeting in Usedom Castle . The temples of the main places of the tribal areas that came under Pomeranian rule and converted into castellanias were razed, for example in Gützkow and Wolgast.

After the death of Bolesław III. in 1138, Duke Henry the Lion of Saxony and Bavaria and the King of Denmark tried to extend their power to Pomerania. In 1147 the Wendenkreuzzug took German and Polish crusaders to Pomerania, which had already become Christian, namely to Demmin and Stettin. After the battle of Verchen in 1164, Henry the Lion made Bogislaw I and Casimir I , the sons of Wartislaw I, dependent on him. In 1168 Jacza von Köpenick transferred the land of the Sprewanen to the griffin dukes. With this and the land of Barnim , their sovereign territory extended between the upper Havel in the west and the Oder in the east, bordering Silesia in the south-east and the margraviate of Meißen in the south-west . In 1177, Heinrich the Lion, in alliance with Margrave Otto I of Brandenburg , undertook another campaign in Pomerania. After a prolonged escalation of the conflict between Heinrich and the Hohenstaufen dynasty, the imperial ban was imposed on Heinrich in 1180 .

In the same year Bogislaw I joined the feudal association of the Holy Roman Empire . In 1181 Emperor Friedrich I Barbarossa raised him and his dynasty to the rank of imperial prince and awarded him the title of Duke of Slavia . From then on, the griffins sometimes referred to themselves as the dukes of Slavia, but sometimes continued to be the dukes of the Pomerania.

In 1185, however, Pomerania was occupied by Denmark and only fell back to the Roman-German Empire after the Battle of Bornhöved (1227) .

In 1231 Emperor Friedrich II confirmed the Margrave Otto III. and Johann I. von Brandenburg their previously granted their father rights over the margravate and in this context also the privilegium liberalitatis una cum ducato Pomeraniæ ("with a Duchy of Pomerania"). “Liberalitas” may mean sovereignty here (Frederick I's documents also contain the phrase “liberalitas nostra”). The translation from 1918 in the Regesta Imperii does not mention that the Latin text speaks of a Duchy of Pomerania without however, to indicate which one was meant. Since the duchy of the Griffins was already an imperial fiefdom, it is often assumed that the Danzig Pomerania was meant here. But since Pomeranian Duke Barnim I did not cede the Land Barnim and the Land Teltow to the margraves until 1237, the Margraviate Brandenburg did not officially border on the Danzig Pomerania in 1237.

Christianization of the imperial fief

Numerous monasteries were founded in Pomerania. In 1180, Premonstratensians from Lower Saxony founded the Belbuck Monastery . Mecklenburg Cistercians founded the Kolbatz monastery in 1173 and the Danish ones in 1199 the Hilda monastery . The Diocese of Cammin was set up in Western Pomerania, initially evangelized from Gniezno , the island of Rügen became part of the Danish Diocese of Roskilde , and the Ranian mainland became part of the Diocese of Schwerin .

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Pomerania, whose population had previously been decimated by the campaigns of Bolesław III, earlier Danish campaigns and epidemics, was increasingly settled by recruited German colonists. The immigration supporters were the Rügen princes and the Pomeranian griffin dukes, who wanted to increase the number of inhabitants and the tax power of their fiefs. These dynasties quickly internationalized through marriage to the European aristocracy and surrounded themselves with German retinues, the choice of name alone reminded of their Slavic roots. The lower Slavic nobility hardly benefited from the expansion of the country and was confronted with strong German competition, as German nobles were also massively recruited and privileged. The rural settlers came mainly from Flanders, (Lower) Saxony, Westphalia, Holland and Denmark, in the southern area around Stettin also from the Harz region. Accordingly, the cities near the coast received the Lübische and the cities of the Szczecin area received the Magdeburg law (in a Stettin modification).

In the places of Slavic origin, the Slavic place name was often retained with a slight adjustment of the sound level (example: Slavic “Pozdewolk” - German “ Pasewalk ”) and the original Slavic population was also included. The colonist villages were either newly created (on cleared forest soil or deserts), or next to or as an extension of Slavic villages, the original Slavic name mostly being transferred to the German village and the Slavic Kietz with the addition "Wendisch-" or "Klein" has been. Otherwise, the place names mostly go back to the locators, who like to transfer their own names to the place (e.g. Anklam from the locator Tanglim). Although in the immediate vicinity, new settlers and long-time residents initially lived culturally and legally in completely different systems. The Flemish people who had arrived and other Germans had arable farming and amelioration techniques that were superior to traditional methods. This was also one of the reasons for their massive recruitment. Recruiting was associated with a number of privileges vis-à-vis the locals. This more advantageous "German" position and the high number of German immigrants subsequently led to an assimilation of the locals by the immigrants instead of the other way around. The result of this process is also known as the new Pomeranian tribe (in contrast to the Slavic Pomorans or Kashubians).

Cities emerged predominantly next to the castle ramparts, with the latter mostly being cleared or demolished in the course of privileging the cities. Thus, around 1250 Greifswald , 1255 Kolberg , 1259 Wolgast , 1262 Greifenberg with Lübischem and 1243 Stettin and 1243/53 Stargard with Magdeburg rights were endowed by the griffin dukes . In the Principality of Rügen, which was not yet part of Pomerania, Stralsund was granted city rights in 1234 .

Soon after the Hanseatic League was founded, the coastal and trading cities experienced an economic upswing that lasted until its decline, accompanied by further privileges and extensive independence from the nobility. They had their own fleets and armed forces. The country towns, on the other hand, remained dominated by agriculture. In addition, there were the country estates of the lower nobility scattered all over the country, who often acted as robber barons and waged downright small wars with the cities.

Split of the griffin duchy

In 1295 the rulership of the Griffin was divided into the Duchy of Pomerania-Stettin (inland part with cities under Magdeburg law on both sides of the Oder and south of the Stettiner Haff ) and the Duchy of Pommern-Wolgast (entire coastal areas with cities of Luebian law , in Western Pomerania north of the Peene including Demmin and Anklam ).

Rügen's gain

The Principality of Rügen (the island of Rügen and the mainland opposite with the cities of Stralsund, Barth , Damgarten , Tribsees , Grimmen and Loitz ) fell to Pomerania-Wolgast after the Rügen princes died out in 1325, but they had to defend this acquisition in the Wars of the Rügen Succession . After its completion, the Danish fiefdom ceased to exist and in 1354 Rügen became an imperial fiefdom . The Duchy of Pomerania-Wolgast was further divided several times until the middle of the 15th century.

Power struggles in the late Middle Ages

After the end of the Danish feudal sovereignty over Western Pomerania in 1227, the Margraviate Brandenburg of the Ascanians raised claims to feudal sovereignty over Pomerania. These claims were supported by Emperor Friedrich II , who in December 1231 in Ravenna renewed the enfeoffment of the Margraves of Brandenburg with Pomerania, which had already been made by Friedrich I, with reference to the ancient rights. In the Treaty of Kremmen (1236) recognized one of the Pomeranian dukes, Duke Wartislaw III. , the Brandenburg fiefdom and ceded areas to Brandenburg. In the event that Duke Wartislaw III. would die without leaving sons if his part of the country fell to Brandenburg. This right of reversal was abolished again by the Treaty of Landin (1250) concluded by Duke Barnim I. After Wartislaw's death his part of the country fell accordingly to Barnim I.

Brandenburg's rights were confirmed again in Mühlhausen in 1295. The result was a series of conflicts between the Dukes of Pomerania (Pomerania was mostly divided at that time) and the Margrave of Brandenburg, such as the North German Margrave War (1308-1317) and the Pomeranian-Brandenburg War (1329-1333). The Pomeranian succession dispute , which broke out in 1294 after the death of the last Duke of Pomerania, Mestwin II , also affected Pomerania.

Under Duke Barnim III. Pomerania was confirmed as a direct imperial duchy in 1348 thanks to good relations with King Charles IV . But soon it was exposed to Brandenburg's striving for power again. It was not until 1529 that Brandenburg finally accepted the imperial immediacy of Pomerania, but in return received the documented right of succession in the event that the Griffin family died out.

1456 was on the initiative of Rubenov by Duke Wartislaw IX. the University of Greifswald founded. In 1466 Duke Erich II acquired the Lauenburg and Bütow lands in the east of Pomerania , which had belonged to the Teutonic Order State since the beginning of the 14th century . Duke Bogislaw X. , the most important duke of the Griffin family (ruled 1474–1523), united Pomerania in 1478. However, the land was provisionally divided again under his successors in 1532 and finally again in 1541/69. This time, however, the dividing line ran along the Oder or Randow, dividing the duchy into a western - Pomerania-Wolgast - and an eastern - Pomerania-Stettin - dominion area.

Reformation and Thirty Years War

From 1534 the Reformation also found its way into Pomerania . In 1536, Duke Philip I of Pomerania-Wolgast was married by Martin Luther to Maria von Sachsen, a daughter of Johann Friedrich I von Sachsen in Torgau . The Pomeranian pastor Johannes Bugenhagen from Treptow an der Rega became, as Doctor Pomeranus, one of the most famous reformers alongside Luther and Melanchthon. He had participated in the draft of the first Pomeranian Protestant church ordinance, written in Low German, which went to print in Wittenberg in 1535 and which formed the basis for the revised Pomeranian church ordinance published in 1542, which was also printed in Wittenberg. By confiscating the extensive ecclesiastical lands, the dukes expanded their position of power in the country.

Under Bogislaw XIV , Pomerania was reunited in 1625. The neutrality of Pomerania during the Thirty Years' War was of little use to the country. Pomerania was mutually plundered by the imperial troops under Wallenstein and the Swedes under Gustav II Adolf . After Wallenstein occupied Pomerania despite the promise of Emperor Ferdinand II , Stralsund in 1628 and in 1630 (not entirely voluntarily) all of Pomerania joined the Swedes.

After the death of Bogislaw XIV, who died childless in 1637, the country should have fallen to Brandenburg , but the Swedes kept the country occupied. Pomerania lost almost two thirds of its population in the Thirty Years War. The country was divided and economically poor.

The oldest weekly newspaper in the region, the report by Pomerania , dates from the 1630s .

Swedish Pomerania

Through the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, Hinterpommern became part of Brandenburg-Prussia and Vorpommern became Swedish-Pomerania .

Sweden received the Pomeranian possessions as an everlasting imperial fiefdom, ie the Swedish kings ruled there with the title and rights of the former dukes from the Greifenhaus . Due to various domestic and foreign policy differences, Sweden received the imperial investiture years later and the agreement with the estates on the state constitution was only achieved in 1663 with the adoption of the form of government, which essentially represented a revised version of the regimental constitution of 1634 , and the subsequent one Homage to the estates. In this constitutional form, that part of Pomerania belonged to Sweden from 1648 to 1806 and was subject to a governor or governor-general, who was appointed by the Swedish king and had to belong to the Swedish aristocracy. The highest court in the Swedish territories on the continent was the Upper Tribunal from 1653 , based in Wismar . Belonging to Sweden, however, had a disadvantage. As soon as Sweden became involved in wars on the continent, Pomerania was also affected. Twice, in 1678 in the Swedish-Brandenburg War and in 1715 during the Pomeranian campaign in the Great Northern War , the Swedes were forced to temporarily evacuate Western Pomerania. In the subsequent peace treaties, parts of the province of Brandenburg were lost: in the Peace of Saint-Germain (1679) most of the areas east of the Oder and in 1720 in the Peace of Stockholm all of the country south of the Peene . From 1720 Swedish Pomerania consisted only of Rügen and the Western Pomerania area north of the Peene. In the period 1715–1721, the part of Western Pomerania north of the Peene was under Danish administration.

In the course of the dissolution of the Old Kingdom in 1806, the status of Swedish Pomerania under state law also changed. Since the estates refused to agree to the creation of a Landwehr demanded by the Swedish King Gustav IV Adolf , on June 26, 1806 the latter revoked the previous estates constitution and the membership of Swedish Pomerania in the empire. This means that this territory left the Reichsverband even before the formation of the Rhine Confederation and the laying down of the imperial crown by Franz II. The introduction of the Swedish constitution and numerous reforms in the legal system, which had already been declared before the Greifswalder Landtag in August 1806 , a. Serfdom was abolished, and because of the French occupation that took place in July 1807, the administration did not come about, or only after a considerable delay.

Transfer to Prussia

After being occupied twice by France and its allies in 1807 to 1810 and in 1812/13, Sweden temporarily regained its last remaining province and, from 1810, at least partially implemented the reforms decided in 1806. In 1813, in a campaign against Denmark , Sweden conquered Norway, which had been in personal union with it until then . In the Peace of Kiel on January 14, 1814, Denmark was offered the prospect of acquiring Swedish Pomerania in return. Since Denmark could not pay the war indemnities imposed on Sweden, Prussia seized the opportunity at the Congress of Vienna and agreed to acquire Swedish Pomerania against cession of the Duchy of Lauenburg to Denmark and assumption of the Danish payments to Sweden. The handover by the Swedish governor general to the prussian representative took place in October 1815. Due to the agreed guarantee of the traditional legal system, the area, which was finally incorporated into the Prussian province of Pomerania as the administrative district of Stralsund in 1818, continued to enjoy a special position for a long time. Colloquially, Swedish-Pomerania is known as "Neuvorpommern" or "Neuvorpommern und Rügen". This was intended to make the distinction to the "Altvorpommern", which had already become Prussian in 1720, to the south and east of the Peene or the Peene River.

Estates and manors

In the interior, Brandenburg-Prussia and Sweden ruled as dukes of Pomerania, whose seat and vote they also had in the Reichstag. Brandenburg, however, took a much more aggressive approach with the adoption of the state parliament in 1654 and curtailed the rights of the states. Sweden did not come to an agreement with the estates until 1663, whereby the ancient fundamental rights were confirmed. In both parts of the country, however, the early modern state established itself through financial and military administration. Swedish Pomerania in particular was considered a highly armed area in the empire.

In the 17th and 18th centuries the farm economy was fully established on the flat land. Concomitant phenomena were serfdom-like legal statuses of the dependent rural population and the so-called peasant laying, i.e. the confiscation of peasant positions in favor of farms. On the other hand, the Prussian kings intervened for military reasons from the middle of the 18th century and forbade the further drawing in of the farms in order not to endanger the recruitment of soldiers on the basis of the cantonal system. Something similar did not happen in Swedish Pomerania, and so at the end of the 18th century the estate economy reached a similar high point as in neighboring Mecklenburg. Ernst Moritz Arndt , himself the son of a freed serf, castigated the related practices in several writings at the beginning of the 19th century.

Around the middle of the 19th century, Pomerania had a total of 73 localities with city rights within the boundaries of the Pomerania province .

Impact of the Versailles Peace Treaty

Pomerania remained largely unaffected by the loss of German territory after the First World War following the provisions of the Versailles Treaty . Only parts of the eastern districts of Bütow , Lauenburg and Stolp with a total of 9.64 square kilometers and 224 inhabitants (registration from 1910) were ceded to Poland.

After the Second World War

At the end of the Second World War , Pomerania was conquered by the Red Army in the spring of 1945 and was subsequently divided by establishing the Oder-Neisse line as a demarcation line between the eastern sphere of influence, which was dominated by the Soviets, and the western sphere of influence .

Shortly after the conquest, Polish administrative bodies were installed in the areas east of the Oder and Swine rivers, with the approval of the Soviet occupying forces. It was not until July 3, 1945 that the provincial capital of Stettin, west of the Oder, was placed under Polish administration by the Soviet Union, after a Polish and a German city administration had initially worked alongside and against each other. Even the German communists were surprised by this step. A Soviet-Polish commission laid down the exact course of the border on September 21, 1945 in Schwerin. In the following weeks, however, the Polish military arbitrarily moved the border in the area around Stettin even further west. The German population in the identified areas under Polish administration was from Pomerania expelled or evacuated later. These so-called "wild expulsions" took place without legitimation through the resolutions of the Potsdam Conference in August 1945. At the same time, Poles immigrated, some of them from the areas east of the Curzon Line that had fallen to the Soviet Union as part of the " West shift of Poland " .

From the part of Western Pomerania that remained with Germany, together with the former State of Mecklenburg , the State of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania was formed at the beginning of July 1945 on the orders of SMAD , which from March 1947 was only called State of Mecklenburg. In 1950 the young GDR recognized the new eastern border as a "peace border" in the Görlitz Treaty . After the administrative reform in the GDR in 1952, the area of Western Pomerania was divided into the districts of Rostock and Neubrandenburg and a small part of the district of Frankfurt (Oder) .

In the course of German reunification in 1990, Germany finally recognized the Oder-Neisse line under international law in the Two-Plus-Four Treaty and in the German-Polish border treaty. With the accession of the GDR to the Federal Republic of Germany in 1990, the federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania was also reconstituted, but with a different regional structure. On the occasion of the district reform of 1994, the districts of Nordvorpommern and Ostvorpommern were established. Furthermore, the districts of Demmin, Rügen and Uecker-Randow as well as the independent cities of Greifswald and Stralsund belong wholly or for the most part to historical Western Pomerania. Efforts to form an administrative district and / or a regional association for Western Pomerania in the tradition of the Prussian provincial associations formed in 1875 as a body of local self-government at the upper level failed.

A small part of Western Pomerania, namely the area of the current Gartz (Oder) office in the Uckermark district formed in 1994 , has belonged to the state of Brandenburg since 1990 .

In order to bring the separate regions of Western and Western Pomerania closer together, the Euroregion Pomerania was founded in 1995 as part of European cooperation . The accession to the Schengen area on December 21, 2007 and also the future accession of Poland to the euro area further contributed to overcoming the dividing line between today's parts of Pomerania.

Since the reform of the administrative structure in Poland in 1999 with the aim of creating new historical territorial divisions, the areas of Pomerania placed under Polish administration in the summer of 1945 have belonged to the West Pomeranian Voivodeships with administrative headquarters in Szczecin and Pomerania (including Pomerellen ) with administrative headquarters in Gdansk .

Due to the demographic development, namely the decline in the birth rate and emigration, the German part of Western Pomerania was essentially divided into the two new greater districts of Western Pomerania-Rügen and Western Pomerania-Greifswald in the course of the Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania district reform in 2011 , which improves the historic Pomerania-Mecklenburg border again should reflect. The administrative offices of the new districts are Stralsund and Greifswald .

literature

- Older treatises

- v. Flemming: The castles of Pomerania . In: Baltic Studies . First issue, Stettin 1832, pp. 96–116.

- Robert Klempin , Gustav Kratz (ed.): Matriculations and directories of the Pomeranian knighthood from the 14th to the 19th century. Bath, Berlin 1863, (full text)

- Johann Carl Conrad Oelrichs : Draft of a Pomeranian mixed library of writings on antiquities, art objects, coins, and on natural history, also on the Cameral and financial affairs of the Duchy of Pomerania. Berlin 1771, (full text)

- Christian Friedrich Wutstrack (Ed.): Brief historical-geographical-statistical description of the Duchy of Western and Western Pomerania. Szczecin 1793.

- Christian Friedrich Wutstrack (Ed.): Addendum to the brief historical-geographical-statistical description of the Duchy of Western and Western Pomerania. Stettin 1795, (full text)

- Gustav Kratz : The cities of the province of Pomerania - outline of their history, mostly according to documents . Introduction and preface by Robert Klempin . Berlin 1865, (full text) .

- Peter Friedrich Kanngießer : History of Pomerania up to the year 1129 . Greifswald 1824 ( e-copy ).

- Johann Ludwig Quandt : The land on the Net and the Neumark, as they were owned and lost by Pomerania . In: Baltic Studies , Volume 15, Stettin 1853, pp. 165–204.

- Johann Ludwig Quandt : Pomerania's eastern borders . In: Baltic Studies , Volume 15, Stettin 1857, pp. 205–223.

- Ludwig Giesebrecht : The land defense of the Pomerania and Poland at the beginning of the twelfth century . In: Baltic Studies . Volume 11, Stettin 1845, pp. 146-190.

- Recent monographs

in order of appearance

- Martin Wehrmann : History of Pomerania , 2nd edition in 2 volumes. Friedrich Andreas Perthes, Gotha 1919 and 1921. (Reprint: Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1992, ISBN 3-89350-112-6 )

-

Hellmuth Heyden : Church history of Pomerania . R. Müller, Cologne-Braunsfeld, 2nd, revised edition 1957

- Vol. 1: From the beginnings of Christianity to the time of the Reformation .

- Vol. 2: From the acceptance of the Reformation to the present .

- Oskar Eggert : History of Pomerania . Volume 1, Hamburg 1974, ISBN 3-980003-6 . (Hans Branig's two-part work is linked to this unfinished book, which traces the history of Pomerania up to around 1300.)

-

Hans Branig : History of Pomerania . Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna

- Vol. 1: From the emergence of the modern state to the loss of state independence 1300–1648 . 1997.

- Vol. 2: From 1648 to the end of the 18th century . 2000.

- Norbert Buske : Pomerania. Territorial state and part of Prussia . Thomas Helms, Schwerin 1997, ISBN 3-931185-07-9 .

- Werner Buchholz (Hrsg.): German history in Eastern Europe. Pomerania . Siedler, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-88680-272-8 .

- Thomas Riis: The medieval Danish Baltic empire. (= Studies on the History of the Baltic Sea Region . IV) Copenhagen 2003, ISBN 87-7838-615-2 .

- Christian Lübke , Henryk Machajewski, Jürgen Udolph : Pomerania. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 23, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-017535-5 , pp. 273-287. chargeable via GAO , De Gruyter Online

- Wolfgang Wilhelmus: History of the Jews in Pomerania . Ingo Koch Verlag, Rostock 2004, ISBN 3-937179-41-0 .

- Michael North : History of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. CH Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57767-3 .

- Kyra T. Inachin: The History of Pomerania. Hinstorff Verlag, Rostock 2008, ISBN 978-3-356-01044-2 .

- Heiko Wartenberg: Archive guide to the history of Pomerania until 1945 (= writings of the Federal Institute for Culture and History of the Germans in Eastern Europe. Volume 33). Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58540-7 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ The name Pomerania (po more) is of Slavic origin and means something like "land by the sea".

- ^ Rudolf Benl: Pomerania up to the division of 1368/72. In: Werner Buchholz (Ed.): German history in Eastern Europe - Pomerania . Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-88680-780-0 , p. 23.

- ↑ Mirozlava Codex Pomeraniae vicinarumque terrarum diplomaticus vol. 1 p. 161 Anno 1233: Dei Patientia Pomeranorum Ducissa ...

- ^ Rudolf Usinger: German-Danish History 1189-1227. Berlin 1863, (full text) .

- ↑ Codex Pomeraniae vicinarumque terrarum diplomaticus vol. 1 p. 150 Ao. 1231: … ejus privilegium liberalitatis inde concessimus inde cum ducatu Pomeraniae eidem Iohanni & Ottoni fratri suo

- ^ Regesta Imperii: Friedrich II. - 1231 dec. 00, Ravenne - enfeoffs the margrave Johann von Brandenburg and possibly his brother Otto and their heirs with the margrave of Brandenburg and all other fiefs which former Albert margrave of Brandenburg bore their father from the rich, and confirms them in the same way the duchy of Pomerania. ( Memento of the original from May 1, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Martin Wehrmann: History of Pomerania. First volume: Until the Reformation (1523) . Waidlich Reprints, Frankfurt am Main 1982, p. 99 (unchanged reprint of the 1904/06 edition)

- ↑ T. Hirsch , M. Töppen , E. Strehlke (eds.): Scriptores rerum Prussicarum - historical sources of Prussian prehistoric times. Volume I, Leipzig 1861, pp. 708–709, note 91 .

- ^ Jacob Caro : History of Poland . Perthes, Gotha, 1863, p 27 .

- ^ Aemilius Ludwig Richter: The evangelical church orders of the sixteenth century. Documents and regesta on the history of law and the constitution of the Protestant Church in Germany . Volume 2: From 1542 to the end of the sixteenth century . Weimar 1846, pp. 1-14. .

- ^ Martin Meier: Western Pomerania north of the Peene under Danish administration 1715–1721 . Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58285-7 limited (preview) .

- ↑ Christian Friedrich Wutstrack (Ed.): Brief historical-geographical-statistical description of the Royal Prussian Duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Szczecin 1793.

- ^ Gustav Kratz : The cities of the province of Pomerania - outline of their history, mostly according to documents. Berlin 1865, p. VII .

- ↑ Eberhard Völker: Pomerania and East Brandenburg. (= Displacement areas and expelled Germans. Volume 9). Langen Müller, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-7844-2756-1 , p. 90.

See also

- Duchy of Pomerania

- Tribe list of griffins

- Pommersches Landesmuseum in Greifswald