Locator

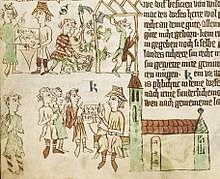

The locator (lat. Locator : lessor, property distributor, from lat. (Col) locare “assign”, “rent”, “establish”, “settle”; also magister incolarum ; in Mecklenburg and Pomerania also posessor or cultor , similar to the Reutemeister in southern Germany) was a medieval subcontractor who was usually responsible for the reclamation, measurement and allocation of land to be developed on behalf of a landlord or landlord . In addition, he recruited settlers for these purposes, provided livelihoods for the transition period (e.g. during the clearing) and procured work materials and tools (seeds, draft animals, iron plows, etc.). He played an important role in the founding of cities and villages as well as the reclamation of uncultivated land during the inland colonization in northern Germany and the German settlement in the east and was thus involved in their success.

Basics, tasks and procedure

Order to colonize

The order for the settlement of the land to be developed was mostly carried out by a noble or ecclesiastical sovereign or by a landlord who had to obtain prior approval from the sovereign. However, villages were also abandoned to locators for reclamation without prior permission, or settlers acted on their own. With regard to the tasks of reclamation and position in the new settlement, it is important to differentiate between town locators and village locators .

Legal basis

The legal basis for the creation of a new settlement was the location contract (lat. Locatio ). This was either concluded directly between the sovereign and the commissioned locator or between the landlord and locator. In the location contract, the location privileges previously agreed with the sovereign as well as the tithe regulations etc. Ä. recorded. The legal and organizational change (in the case of the German eastern settlements, the change from Polish to German law ), benefits for locators and settlers as well as duties and tax charges were contractually regulated. This also included the requirement to secure the fields against flooding or other natural influences or to protect the settlement e.g. B. to protect against enemies by digging a trench. The location contract thus had a binding effect on the landlord for the settlers and locators, but also formed a legal basis that means legal security for the settlement and its residents. Often the locatio also contained penal clauses which, in the event of a failed settlement, would result in the withdrawal of privileges and a fine for the locator.

Social position

Locators belonged mainly to the lower nobility or the class of townspeople. They were knights or vassals of the sovereigns. Often they were also people who had respected professions, such as mint masters or royal servants. In addition, they usually had sufficient experience or a good education at the time. There have also been reports of simple farmers acting as locators, but this practice was rather unusual. Because usually the locators had to have a greater wealth and good social connections. The landlords and sovereigns preferred to award location contracts to people who needed little or no financial support in order to minimize their own risk.

Procedure and tasks

The locator can be described as a middleman between the landlord and the settlers who was primarily responsible for recruiting. He often led or supported the advertising campaign initiated by the landlord . He carried out the construction of the local facility to be created under his own direction and responsibility and distributed the tasks in the course of the reclamation. The basic tasks of the locator also included measuring the allocated land and distributing it to the individual settlers. He often led the lottery procedure or divided the land as fairly as possible in order to avoid confrontations from the start. In addition, he provided seeds, tools and other work materials that were necessary for the establishment of the settlement, reclamation (especially in the case of the eastern settlement, for example, the draining of swampy areas) and other tasks. Advances for purchases and subsistence for the settlers in the transition period were mostly borne by the locator. The locator was also the deputy for the settlers he looked after.

Technical background

Mountain observations and smoke signals as landmarks were means by which the locator roughly delineated the land. To measure the settlement more precisely, trees were scratched in heavily forested areas and the area was delimited with a plow in open terrain. The division and allocation of the individual parcels for the settlers took place in the land survey mostly using measuring rods or measuring ropes. Depending on the settlement, the measurement basis was either the Flemish hoof (approx. 16 hectares) or the Franconian hoof (approx. 24 hectares).

The locator after the settlement is finished

With the establishment of a settlement, the actual task of a locator was done. If it was not a question of a professional locator who went over to the establishment of further settlements, the locator stayed at the place of establishment and assumed a prominent position there.

Economic background

The locator usually received more land than the other settlers and, in contrast to the other settlement residents, had to pay little or no taxes on it. In addition, he was subject to jurisdiction according to the law applied in the location contract, often as a so-called Lehnschulze . The locator was allowed to keep some of the fees and taxes obtained from this (usually 1/3 of the sum, with 2/3 to be paid to the sovereign).

Social position, rights and obligations

Other privileges, such as the right to exercise an office in the new settlement (often that of the Schulzen ) or to pursue a certain activity (brewing / serving), were privileges that the locator enjoyed and that led to prosperity and social advancement within the settlement helped. The construction of a mill, in which the settlers had to have their grain milled, was also often allowed to the locator and means an additional source of income with regard to the fees incurred as a result, whereby the majority of this income mostly went to the landlord. In addition, the resulting settlements were often named after their location. There are plenty of examples (Diedersdorf, Dittmannsdorf, Dittersbach, Petersheide, Heinersdorf, etc.). The name of the settlement often indicated where the settlers and the locator came from (Frankenfelde, Flemmingen, Sachsenfeld, Schoobsdorf and others). The endings of the place names are also clear indications of the origin of the inhabitants of the settlement at that time.

Alternative approach

Some locators sold their rights and privileges after the settlement was completed and operated as locators again elsewhere. This resulted in a comparatively high level of professionalism in the local community. Some locators could therefore be called professional locators.

literature

- Matthias Hardt : Lines and seams, zones and spaces on the eastern border of the empire in the early and high Middle Ages. In: Walter Pohl, Helmut Reimitz (Ed.): Limit and Difference in the Early Middle Ages (= memoranda (Austrian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class), 287th volume). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2000, ISBN 978-3-7001-2896-0 , pp. 39–57.

- Matthias Hardt: Forms and ways of establishing settlements in the High Middle Ages. In: Enno Bünz (Hrsg.): Ostsiedlung and Landesausbau in Sachsen: the Kührener deed of 1154 and its historical environment (= writings on Saxon history and folklore, volume 23). Leipziger Universitätsverlag , Leipzig 2008, ISBN 978-3-86583-165-1 , pp. 143-160.

- Herbert Helbig (Ed.): Central and Northern Germany, Baltic Sea Coast (= documents and narrative sources on German settlement in the Middle Ages. Volume 1). Darmstadt 1975, ISBN 3-534-05960-3 .

- Franz Kössler : The descendants of the locator - on the settlement history of a German-speaking landscape in the Bohemian-Moravian region. Hess, Bad Schussenried 2010, ISBN 978-3-87336-913-9 .

- Paul Richard Kötzschke : Entrepreneurship in the East German colonization of the Middle Ages. Bautzen 1894. (Diss.)

- Josef Joachim Menzel : The contribution of document science to research into the German settlement in the east using the example of Silesia. In: Walter Schlesinger (Ed.): The German East Settlement of the Middle Ages as a Problem of European History (= Reichenau lectures 1970–1972 ). Sigmaringen 1975, pp. 131-159.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ A XVI. Document book of the Archbishopric Magdeburg I, No. 310-UB Monastery ULF Magdeburg, No. 33-Winter, Premonstratensian certificate, No. 7-Kötzschke, No. 18-von Mülverstedt, Reg. Archiep. Magdeburg I, No. 1442.

- ↑ Menzel 1975, p. 146.

- ↑ A XVI. Document book of the Archbishopric Magdeburg I, No. 310-UB Monastery ULF Magdeburg, No. 33-Winter, Premonstratensian certificate, No. 7-Kötzschke, No. 18-von Mülverstedt, Reg. Archiep. Magdeburg I, No. 1442.

- ^ Heinrich Kaak: The Brandenburg village as a scene of social and economic developments (15th to 19th centuries), p. 2.