Friedrich II (Prussia)

Friedrich II. Or Frederick the Great (born January 24, 1712 in Berlin ; † August 17, 1786 in Potsdam ), popularly known as "Old Fritz", was King in 1740 , King of Prussia from 1772 and Margrave of Brandenburg from 1740 and thus one of the electors of the Holy Roman Empire . He came from the Hohenzollern dynasty .

The three Silesian Wars he waged against Austria for possession of Silesia led to German dualism . After the last of these wars, the Seven Years' War from 1756 to 1763, Prussia was recognized as the fifth great power alongside France , Great Britain , Austria and Russia in the European pentarchy .

Friedrich is considered a representative of enlightened absolutism . He described himself as “the first servant of the state”. He carried out far-reaching social reforms, abolished torture and pushed ahead with the expansion of the education system.

Dynasty, territorial union, means of power, land and people

Typical tools for exercising power were available to Friedrich for the modern era. A characteristic of early modern rule is that the territories that were brought together through marriage, inheritance and war, which differed greatly from one another in terms of structure, were primarily brought together and held by the dynasty. It was only with the acquisition of the royal crown in 1701 that the territories of Brandenburg-Prussia, which were scattered across the entire Roman-German Empire, became externally perceptible to a state unity, through the dynasty and its representation on the European level, its perception from the outside, but also through the seemingly solid army grew together. This specific process of dynastic state formation and unification was mainly driven by Friedrich's ambitious father . The Hohenzollern came from southwest Germany; they can be traced back to the 11th century. At the beginning of the 15th century, as loyal burgraves of Nuremberg, enfeoffed with the Margraviate of Brandenburg , they rose to become electors . The new territory was used for a long-term consolidation policy , whereby with the inheritance of the Duchy of Prussia , which lay outside the Imperial Association, the claim to the royal crown had to be legitimized. Friedrich saw himself as the continuer and finisher of the traditions that were thus founded and of his father's striving for great power.

In 1740 there were 2,240,000 people living in Friedrich's inheritance, in 1784 he considered 5.5 million people to be his subjects in his rapidly growing state. If one disregards the territories on the Lower Rhine and in Westphalia , i.e. Kleve , Mark and Ravensberg , which had come to Brandenburg since the Treaty of Xanten , Friedrich ruled over an agricultural, urban-poor area with an undeveloped infrastructure. This and the territorial fragmentation made economic development extremely difficult. But there was a hierarchical, orderly administration, at the head of which was the General Directory created in 1723 . This brought the General War Commissariat and the Domain Directorate together, the former being mercantilistically oriented. But not only this administrative unit was unusual, but also the strict division of departments - signs of a modernized administration with economic intentions geared towards the state budget. The relevant college resided in the Berlin City Palace ; it was responsible for domestic politics as well as for financial management, military economics and war provisions. It was composed of four provincial departments. Overall, a mixture of territorial and factual responsibilities typical of the time. Friedrich continued this inherited regiment and only deepened the differentiation between departments. His fifth department for “Commercien- und Manufactur-Matters”, which was set up after the assumption of power, had exclusive national jurisdiction. Friedrich did not take part in the meetings any more than his father did. Instead, the decisions were made in the royal study and commissioned by cabinet secretaries. While the war and domain chambers were assigned to the directorate, the district administrator ruled in the country. He was almost always resident in his area of office, was proposed by the local nobility and almost always accepted. In the ideal case, he mediated between the interests of the aristocrats, who insist on autonomy, and the ordinances of the sovereign authorities.

The cabinet ministry created by Friedrich's father remained in place for foreign policy. It was responsible for the correspondence with the foreign authorities as well as with the business representatives accredited there. The original first central authority, the Secret Council , established in 1604 , survived, but dealt only with justice, spiritual affairs, and education. At the end of his reign, Friedrich had around 300 civil servants, including the tax and district administrators, there were around 500 officials. The form of government that is widespread in Europe and strives for unrestricted rule is called absolutism, even if it can only describe the top level of a complex process. The concept of enlightened absolutism was only introduced in 1847 by Wilhelm Roscher , who, in its outline on the natural doctrine of the three forms of government, ranged between an early confessional absolutism in the time of Philip II (1527–1598), a courtly absolutism of Ludwig XIV. And an enlightened absolutism of Frederick II . difference.

Society was divided into three classes, nobility, townspeople and peasants, but the subordinate residents made up the majority of the population. While free peasants and nobility were subject to a certain concurrence of interests, the manor in the central and eastern territories had lowered the rural population into subservience and serfdom . About a quarter of the cultivated area was sovereign share, although this was much higher in the Duchy of Prussia. Increasing the ruler's share was long considered a means of asserting against the particular powers, but Friedrich, whose father had decided this fight, again included the nobility and their land more strongly in the apparatus of power and promoted the nobility, on their participation in diplomacy, military and Administration he was increasingly dependent. For this nobility, however, it was not befitting to earn a living in civil professions. This, given that there were about 20,000 noble families, but a limited number of estates, resulted in severe impoverishment of the nobility. In order not to exacerbate this through the acquisition of goods by citizens, Friedrich deliberately obstructed this acquisition. His engagement against mesalliances , the marriage between members of different classes, was on the same line . The rise to the nobility was almost impossible. Probably unintentionally, a bourgeois consciousness and commitment arose on this basis, but this did not lead to the fundamental criticism of the aristocracy as in France. Friedrich himself demanded in his Political Testament of 1752 that the king had to strike a balance between the interests of the peasants and the nobility, which, however, was hardly possible in view of the dependence of his rule on the nobility. In addition, it was difficult for the monarchy to have direct access to the subordinate rural population, over whom the noble landlord sat in judgment. This in turn was a motive to recruit farmers from abroad who were exempt from this ancient system. They were also spared from military service. Between these poles of the feudal system were the citizens, who were mostly engaged in handicrafts and small businesses. There were also wealthy entrepreneurs, merchants and bankers, scholars, clergymen and civil servants. Although they lived in cities that had lost their special role as a result of being included in the state financial administration, they remained important trading centers for goods. But now the residences advanced to the center of bourgeois life. Opportunities for advancement existed in the military for non-nobles only in a few technical areas, hardly in administration. But precisely in those areas in which the highest level of competence was required, their number under Friedrich exceeded those from the nobility many times over.

The Huguenots who immigrated from France and fled from 1684 played a special role . In 1699, 5,682 of the 14,000 refugees living in Prussia were living in the capital Berlin . In 1724 they made up almost 9% of Berlin's population and provided society with countless economic and cultural impulses. In stark contrast to this was the Jewish community, about whose members Friedrich repeatedly expressed derogatory comments. It was newly created in 1671 by religious refugees, this time from Austria, but enjoyed no privileges, and they also had no access to the guilds and were thus excluded from the trade. In 1688 there were 40 Jewish families living in Berlin and by 1700 there were already 117. The first synagogue, later called the Old Synagogue , was built in 1712 . Despite special taxes and disabilities, some of Berlin's Jews made fortunes in the financial and banking sectors. In 1749 there were 119 large Jewish entrepreneurs living in the capital. The tolerance that prevailed at least between the Christian denominations had its roots in the - an unusual case in Europe - little noticeable division between the Lutheran regional church and the Calvinist dynasty since Johann Sigismund converted in 1613. Then there were the numerous Huguenots and, since the conquest of Silesia, the Catholics there. Here lay pietism quite in line with the state of the king conception.

Thanks to his father's thrift, Friedrich had a state treasure of 8.7 million thalers at his disposal when he took office. The expansion of the canals between the Oder and Elbe should strengthen trade in bulk goods such as grain, salt and wax, wood and potash . These waterways made Berlin a hub of industrial production, trade and trade, whereby Friedrich was able to tie in with traditional funding mechanisms. In addition to civilian production for linen or silk , the armaments industry such as the Spandau rifle factory flourished, with guns, mortar shells and artillery ammunition still being procured from Sweden and Holland. Some of the royal businesses were run by private manufacturers, such as the merchants Splittgerber & Daun (founded in 1712), who were the most important entrepreneurs of this type and ran eight businesses. Supplies for the army were created across the country, but also raw materials for wool processing. With the grain, in turn, the food prices could be influenced. At the same time, the military career was increasingly seen as a noble profession, Friedrich viewed the officer's craft of war as a "métier d'honneur" (about: honorary occupation ). Overall, the process of militarization was accelerated considerably under Friedrich.

Life until assumption of power

Early Years (1712-1728)

Friedrich was born in the Berlin City Palace . He was the oldest surviving son of a total of seven sons and seven daughters of King Friedrich Wilhelm I and his wife Sophie Dorothea of Hanover . Four of his siblings died as children. The family tree of Frederick the Great shows the ancestral decline that is often encountered in high nobility circles . Since his parents were first cousins, as were his mother's parents, the number of his great-great-grandparents was reduced from 16 to 10. On January 31, 1712 he was baptized under the sole name of Friedrich, his two older brothers had since died . Until his sixth birthday, Friedrich lived with his older sister Wilhelmine , who in turn was the oldest surviving daughter. He had a close relationship of trust with her all his life. The two lived in the care of the French-speaking Marthe de Roucoulle , a French-born Huguenot who had already looked after his father as governess .

Friedrich then received a strict, authoritarian and religious upbringing according to the detailed instructions of Friedrich Wilhelm, who meticulously prescribed the daily routine of the Crown Prince , from "having breakfast in seven minutes" to washing hands at 5 o'clock. Then he should go to the king, then he should "ride out, divert himself in the air and not in the chamber", where he could then do "whatever he wants, if only it is not against God". Friedrich's tutor, Jacques Égide Duhan de Jandun , appointed in 1716 , a Huguenot refugee who the king had noticed during the siege of Stralsund in 1715 with his special bravery, taught Friedrich until 1727. Duhan developed a close personal bond with his pupil, which he expanded The timetable was strictly edited by the king, in which he also introduced the prince to Latin and literature, and finally also helped with the acquisition of the secret library of the heir to the throne. Latin lessons also took place in secret, and when his father caught them doing it, he punished teachers and students alike with punches and kicks.

Conflict with the father (1728–1733)

In 1728 Friedrich began secretly to take flute lessons from Johann Joachim Quantz , which intensified the conflicts between the tyrannical father, who was only fixated on the military and economic issues, and the Crown Prince. Brutal corporal and mental punishment by Friedrich Wilhelm was the order of the day in the royal family at that time. At the same time, the young Friedrich heated up these conflicts again and again through his emphatically rebellious behavior towards his father.

In 1728 Friedrich accompanied his father on a state visit to the Dresden court during the carnival celebrations . There he fell in love with the illegitimate daughter of Elector Friedrich August, Anna Karolina Orzelska . The relationship was continued when Friedrich August made a return visit to Berlin in the same year.

In 1729 Friedrich sought a close friendship with the artistic and educated Lieutenant Hans Hermann von Katte , eight years his senior . Katte became a friend and confidante of Friedrich, who admired him for his cosmopolitanism. Both were also interested in playing the flute and poetry. In the spring of 1730, during an event organized by August the Strong in Zeithain near Riesa ( Lustlager von Zeithain ), Friedrich revealed to his friend the plan to flee to France in order to evade the educational powers of his strict father. Friedrich Wilhelm I found out about the escape plans through Heinrich von Brühl and beat Friedrich in front of the assembled court society in the presence of Brühl, with whom he led a lifelong personal feud from then on. This event and further personal resignations, also by the present Elector Friedrich August I, led to a future strain on Prussian-Saxon relations . The subsequent attempt by Friedrich to escape in the camp failed because the horses were not released. The Crown Prince then accompanied his father on a diplomatic trip through southern Germany. On the night of August 4th to 5th, 1730, Friedrich tried unsuccessfully, together with the page Keith , to flee from his travel quarters near Steinsfurt via France to England, while Katte was exposed by a compromising letter as a confidante and arrested a little later. Friedrich himself was placed under arrest in the Küstrin fortress .

First Katte was one of the Schloss Koepenick meeting participants Prussian court martial for desertion to life imprisonment sentenced. Friedrich's father, however, had the court informed that it should sit down again and pass a new verdict, with which he unequivocally requested the judges to impose a death sentence on Katte. Finally, Friedrich Wilhelm himself converted the verdict - which was still imprisonment for life - into a death sentence on November 1, 1730 by means of the highest cabinet order. It was carried out by beheading on November 6th in the Küstrin fortress. Friedrich, who was supposed to watch, had been able to say goodbye to Katte by shouting out and passed out while the death sentence was being read out. Other people close to the Crown Prince were also severely punished, such as the Potsdam rector's daughter Dorothea Ritter , a musical friend of Friedrich's, and Lieutenant Johann Ludwig von Ingersleben , who had accompanied Friedrich when he met Dorothea.

The king, who initially also wanted to execute Friedrich for treason, finally spared him, on the one hand at the intercession of Leopold von Anhalt-Dessau , on the other hand also for reasons of foreign policy, after both Emperor Karl VI. as well as Prince Eugene had written for the Crown Prince. But he was sentenced to imprisonment in a fortress in Küstrin.

His princely status was temporarily stripped of his status. Initially arrested, he served in the Küstriner War and Domain Chamber from 1731 until he was reassigned to the army in November and was stationed in what was then Ruppin in 1732 as the owner of the former regiment on foot from the Goltz (1806: No. 15) . So he got to know army and civil administration firsthand. After he had agreed to marry the unloved Elisabeth Christine von Braunschweig-Bevern - the daughter of Duke Ferdinand Albrechts II of Braunschweig - in 1732 , the conflict with the father was outwardly settled and Friedrich rehabilitated as Crown Prince.

Years as Crown Prince in Ruppin and Rheinsberg (1733–1740)

Friedrich and Elisabeth Christine married on June 12, 1733 in Salzdahlum Castle . There was ballet , a pastoral in which the crown prince, who played the main role, played the flute , and operas by Carl Heinrich Graun and Georg Friedrich Handel . The marriage remained childless, which some researchers attribute to a sexually transmitted disease which he contracted shortly before the marriage during a visit to the court of Augustus the Strong and which prevented him from performing the sexual act. Other scientists, however, assume that Friedrich, like his brother Heinrich, was homosexual .

With his father's permission, the Crown Prince moved with his wife to Rheinsberg in 1736 and resided there at Rheinsberg Castle . He spent the following years there with his own court until his father's death in 1740. During this time he devoted himself to the study of philosophy, history and poetry in a self-created circle of mostly older aestheticians and artists who stayed in Rheinsberg or with whom he corresponded, such as Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff , Charles Étienne Jordan , Heinrich August de la Motte Fouqué , Ulrich Friedrich von Suhm and Egmont von Chasôt .

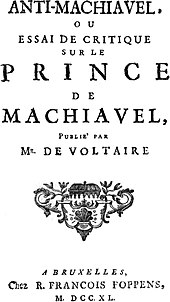

In 1738 Friedrich composed his first symphony . One year later, in 1739, Friedrich, who was already corresponding with the pioneer of the Enlightenment, Voltaire , wrote the Antimachiavel , a catalog of virtues of the enlightened ideal monarch. Later important political writings were the Political Testament (1752) and Forms of Government and Ruler's Duties (1777), in which he outlined his understanding of enlightened absolutism .

During the years in Rheinsberg, Friedrich maintained polite and courteous dealings with his wife, but after his accession to the throne, as he had announced before the forced marriage, he excluded Elisabeth Christine from his environment. While Friedrich retired from court life in Charlottenburg Palace , he assigned her an apartment in the Berlin City Palace and gave her Schönhausen Palace as a summer residence .

Friedrich II as king

Beginnings 1740-1745

First reforms (1740)

On May 31, 1740, Friedrich II ascended the Prussian throne after the death of his father. The abolition of torture was one of his educational measures . Torture had long been rejected by the German and European public as barbarism, and scholars such as Christian Thomasius , whom Friedrich admired , had called for its abolition. Friedrich also saw torture as a cruel and uncertain means of ascertaining the truth and was of the opinion throughout his life that "it would be better for twenty guilty people to be acquitted than for one innocent person to be sacrificed". Despite the contradiction of his justice minister Samuel von Cocceji and other advisors, the king ordered by edict as early as June 3, 1740 , “in the case of which inquisitions completely abolish torture, except for the crimen laesae maiestatis and treason there , also in the case of great murders, where there are many people killed or many delinquents whose connexion is necessary to bring out, implied ”. Friedrich also decreed that from now on there was no longer any need to make a confession for a conviction if "the strongest and clearest indicia and evidence from many unsuspecting witnesses" are available. With the deterrent effect of torture in mind, Friedrich had Cocceji announce the edict to all courts, but, in contrast to the practice of legal texts, prohibited its publication. Torture was abolished unconditionally in 1754, after having probably only been used in one case in the meantime.

The tolerance and openness towards immigrants and religious minorities such as Huguenots and Catholics, which was not entirely unselfish in economic terms for Prussia, was not a reform, but was already practiced before his term in office. The winged saying (June 22, 1740) " Everyone should be saved according to his own style " summarized this practice only in a catchy formula. Frederick II also followed the policies of his predecessors in the discriminatory treatment of Jews ( revised general privilege 1750). With the consent of the Breslau prince-bishop, he issued an edict on August 8, 1750, according to which "the sons in the religion of the father, the daughters in the religion of the mother" had to be instructed in marriages between Protestant and Roman Catholic partners.

Friedrich was very open to new industries. In 1742, for example, by edict he ordered the planting of mulberry trees for silkworm breeding in order to become independent of foreign silk deliveries.

When he took office, he commissioned Professor Jean Henri Samuel Formey to found a French newspaper for politics and literature in Berlin. The order was issued to the Minister Heinrich von Podewils to lift the censorship for the non-political part of the newspapers. Political statements, however, were still subject to censorship. Prussia was the first absolute monarchy in Europe to introduce at least limited freedom of the press. In addition, it was possible for all citizens in Prussia to address the king by letter or even personally. He tried to prevent excessive excesses of the feudal system . In doing so, he was particularly suspicious of his own officials, whom he assumed had a pronounced sense of class to the detriment of the poorer classes.

Soon after his accession to the throne, the king traveled to Königsberg to pay homage to the estates and then to Strasbourg incognito via Bayreuth , and then to his Lower Rhine provinces. He met Voltaire for the first time at Moyland Castle in mid-September . With a stroke of hand he forced the Prince-Bishop of Liège to redeem the glory of Herstal . From mid-November to early December 1740 Voltaire visited the king again in Rheinsberg.

The first two Silesian Wars (1740–1745)

Six months after his accession to the throne in 1740, Friedrich began the First Silesian War on December 16 . The trigger for his attack on Silesia was the death of the Habsburg Roman-German emperor Charles VI. who had remained without a male heir. His eldest daughter, Maria Theresa , succeeded him in accordance with a regulation of succession to the throne, the so-called pragmatic sanction , which had already been ordered during his lifetime in 1713 . This legacy also aroused the desires of other neighbors who were related to the House of Habsburg, so that after the first Prussian victory in the Battle of Mollwitz, Bavaria , Saxony and - under a pretext - France followed Frederick's example and attacked Maria Theresa. This widened the initial conflict over Silesia into the War of the Austrian Succession . Friedrich used this for his limited war aims, secured the cession of Silesia as " sovereign possession " in the separate peace of Breslau in 1742 and left the anti-pragmatic coalition.

The military tide turned in the following year of the war: Although the House of Habsburg lost the imperial throne to Karl Albrecht of Bavaria , Maria Theresa's troops were able to assert themselves with English support and even go on the offensive. In this situation Friedrich began to fear for the permanent possession of Silesia and entered the war again in 1744 on the side of Austria's opponents. He claimed to want to protect the Wittelsbach emperor and marched into Bohemia , again breaking the treaty and opening the Second Silesian War . This cemented Friedrich's reputation as a highly unreliable ally. The Prussian attack on Bohemia failed, however, and Friedrich had to retreat to Silesia again. The Austrian troops followed, but lost decisive field battles, and so Friedrich was finally able to secure his Silesian conquests again in the Peace of Dresden in 1745 .

The young German newspaper world reported partially on the war. One of the papers hostile to Prussia was the Gazette de Gotha , which, like the Gazette d'Erlangen, aroused Friedrich's personal displeasure. On April 16, 1746, in a letter to his sister Wilhelmine, he complained about the “insolent lout of newspaper makers from Erlangen who publicly slandered me twice a week” and asked her, in her role as Margravine of Bayreuth, to put an end to this hustle and bustle . However, she did so only half-heartedly, and the editor of the Gazette d'Erlangen Johann Gottfried Groß then always withdrew briefly to the neighboring free imperial city of Nuremberg . With a thug hired by his confidante Jakob Friedrich von Rohd , Friedrich had the editor of the widely spread Catholic Gazette de Cologne , which regularly exaggerated Austrian successes and suppressed Prussian victories, beat Jean Ignace Roderique on the street. In his anger, the king even dedicated a humiliating poem in French to him.

Acquisition of East Frisia (1744)

In 1744, East Frisia fell to Prussia by inheritance, which Friedrich Wilhelm had already speculated about in his political will in 1722. When Carl Edzard , the last East Frisian prince of the Cirksena family , died childless on May 25, 1744 , at the age of 27, King Friedrich II of Prussia asserted his right of succession, which had been regulated in the Emden Convention, which had been concluded two months earlier . He had East Frisia occupied from Emden, whereupon the country paid homage to the crown on June 23.

Seven Years War (1756–1763)

Beginning of the war (1756–1757)

After a mainly to activities of the Austrian Chancellor Kaunitz declining reversal of alliances (including France became the supporters of Maria Theresa and England for a friend of the Prussian king), Frederick end of August 1756 his troops without declaring war in the Electorate of Saxony invaded and opened so the later so called Seven Years War. With that he came a few months before an already agreed coordinated attack by an alliance of practically all of Prussia's direct neighbors, including the great powers Austria, France and Russia. Because of his strategic skill, he was finally given the nickname “the great”, an epithet that Friedrich was very interested in, as Jürgen Luh was able to prove on the basis of his correspondence with Voltaire . In this sense, his personality was also staged. Friedrich was the last European monarch to be so named according to old European tradition, which is related to the displacement of historical personality by the idea of the nation in the wake of the French Revolution .

As one of the few monarchs of his time, he always led his troops personally. As a general, he won the battles Lobositz 1756, Prague 1757, Roßbach 1757, Leuthen 1757, Zorndorf 1758, Liegnitz 1760, Torgau 1760, Burkersdorf 1762. He was defeated three times ( Kolin 1757, Hochkirch 1758, Kunersdorf 1759). He was far less successful in the siege war. A victorious siege ( Schweidnitz 1762) faced three failures (Prague 1757, Olmütz 1758, Dresden 1760). Although Friedrich lost the nimbus of invincibility due to the defeat of Kolin, his opponents continued to regard him as very fast, unpredictable and difficult to conquer.

The defeat of Kolin destroyed Friedrich's hope for a short, uncomplicated campaign. From now on he prepared himself for a long battle with arms. His mental situation deteriorated increasingly, especially when he learned that ten days after the battle his beloved mother Sophie Dorothea had died in Berlin. A letter to the Duke von Bevern on August 26, 1757 impressively demonstrates his hopeless mood:

“Those are hard times, God knows! and such dizzying circumstances that it takes a cruel void to get out of it all. "

On the verge of defeat (1758-1760)

The Prussian state finances were hopelessly shattered and the war could no longer be financed with the resources available. As the tenants of all mints, Veitel Heine Ephraim and Daniel Itzig offered the oppressed monarch to secretly lower the silver content of groschen and talers, and they produced millions of Ephraimites . The king assured them of impunity and had most of the documents destroyed which showed that the government was involved in the systematic counterfeiting .

After the catastrophic outcome of the Battle of Kunersdorf in August 1759, Frederick II was no longer able to command the army for a while. On the evening of the battle he transferred the supreme command to his brother Prince Heinrich and wrote to the Minister of State Count von Finckenstein in Berlin:

“I attacked the enemy at eleven o'clock this morning. We pushed them back to the Judenkirchhof near Frankfurt . All of my troops have performed miracles of bravery, but this churchyard has cost us tremendous losses. Our people got mixed up, I ranked them three times, in the end I was about to get caught myself and had to clear the battlefield. My clothes are riddled with bullets. Two horses were shot in the body, my misfortune is that I am still alive. Our defeat is enormous. I don't have three thousand out of an army of 48,000 men. As I write this, everything is fleeing and I am no longer master of my people. You will do well in Berlin to think about your safety. This is a cruel setback, I will not survive it; the consequences of this meeting will be worse than the meeting itself. I have run out of reserves and, so as not to lie, I believe that all is lost. I will not survive the fall of my country. Goodbye forever! Friedrich "

After Kunersdorf the total defeat for Prussia was imminent. Friedrich himself was deeply affected: “It can be assumed”, writes Wolfgang Venohr , “that Friedrich played with thoughts of death in the first terrible days after Kunersdorf.” But an unexpected turn came about: Instead of marching on Berlin, Austrians and Russians hesitated two whole weeks until they moved eastward on September 1st. Friedrich was temporarily saved and spoke with relief of the " miracle of the House of Brandenburg ". On September 5, he wrote to Prince Heinrich from the Waldow camp on the Oder:

“I received your letter on the 25th and I announce the miracle of the House of Brandenburg: While the enemy was crossing the Oder and only needed to risk a [second] battle to end the war, he marched from Müllrose to Lieberose. "

The turning point: Russia's exit

The turning point came when the Russian Tsarina Elisabeth died on January 5, 1762 . Elisabeth's successor Peter III. revered Friedrich and surprisingly concluded an alliance contract with him . After Peters was murdered in July 1762, his widow and successor Catherine II dissolved the alliance, but did not resume Elizabeth's anti-Prussian policy. With that the anti-Prussian coalition broke up. Maria Theresa and Friedrich signed the Treaty of Hubertusburg in 1763 , which laid down the status quo ante and was signed on February 21, 1763 in Dahlen Castle .

Reconstruction and late acquisitions (1763–1779)

Reconstruction inside

Under Frederick II, Prussia had asserted itself against the resistance of three European great powers (France, Austria, Russia) and the Central Powers (Sweden, Electoral Saxony) and established itself as a new great power. However, Friedrich had aged early due to the hardships and personal losses of the campaigns. The young king's intellectual open-mindedness from his first years in reign gave way to bitterness and pronounced cynicism . Nevertheless, in 1763 he had given Prussia a secure base in the political concert of the powers of that time and established it as the fifth major European power alongside Russia, Austria, France and England.

He made a contribution to the development of law, in particular general land law . Further domestic political acts after 1763 included the promotion of potatoes as food in agriculture - for example, on March 24, 1756, in the so-called potato order , he ordered all subjects to make the cultivation of potatoes "understandable" to all subjects. The Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Berlin was founded by him in 1763, and he gave it his royal trademark with the blue scepter. After 1763, Friedrich continued the expansion of the state in the Warthe , Netze- and Große Bruch , which had already been successfully completed in 1762 in the Oderbruch . In 1783, after many years of negotiations with neighboring states, including in the Calvörde district of Brunswick , the draining of the wild Drömling began . In the newly developed areas, villages were built and free farmers settled. When a lease agreement was due to be extended for state reasons, it was customary for employees, maids and servants to be asked about their treatment and, in the event of grievances on the part of the tenants, to be exchanged.

The abolition or mitigation of serfdom , which he wanted and suggested , was only able to enforce step by step in the royal crown domains. A general abolition failed due to the resistance of the aristocratic landowners who were firmly anchored in society .

Hundreds of schools were built during the reign of Frederick. However, the rural school system suffered from the unregulated teacher training. Often former NCOs were called in who were only incompletely capable of reading, writing and arithmetic.

After the end of the Seven Years' War, he ordered the construction of the New Palace on the west side of Sanssouci Park , which was completed in 1769 and which was mainly used for guests of his court. In 1769 he was busy with his nephew and his cousin, namely with the divorce between Elisabeth Christine Ulrike von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel and the heir to the throne Friedrich Wilhelm II.

Foreign policy

After the Seven Years' War, Frederick had neither an alliance with Great Britain nor an alliance with France: he resented the separate Peace of Fontainebleau of 1762 for the British, and he only had contempt for the military power of the French. On the other hand, he had respect for Russia: in his political will of 1752 he had impressed on his successor to avoid a war against Russia as much as possible, especially since there was no reason to do so: “There are no disputes between him and Prussia. Only coincidence makes it our enemy. ”When Empress Katharina asked in 1764 how Friedrich felt in view of the foreseeable death of King August III. Intended to restrain Poland , he took the opportunity and negotiated a formal alliance. On March 31, Jul. / April 11, 1764 greg. the agreement was signed, which, in addition to cooperation with Poland, provided for a mutual guarantee of borders and mutual support in the event of war. This alliance was extended in 1769 and 1777. It was to become the central pillar of Frederick's foreign policy for the next twenty years.

This alliance proved its worth in the course of the first partition of Poland in 1772. In his Political Testament of 1752, Friedrich had already speculated about an acquisition of Polish Prussia, later known as West Prussia , in order to obtain a land bridge between Pomerania and East Prussia . One opportunity arose in 1769 when Austria occupied the Spiš in order to get compensation for the lost Silesia. Poland could not defend itself because the civil war was raging here over the Confederation of Bar , which wanted to end the de facto protectorate that Russia exercised over the Rzeczpospolita . This civil war and the Russian involvement in it presented the Empress Katharina with a dilemma: she could neither tolerate the Polish insubordination, nor could she provoke Prussia and Austria, which insisted on maintaining the balance of power, through forced military intervention. This balance seemed to be completely overturned when Russia achieved great successes in the concurrent Russo-Ottoman War .

When Austria's intervention seemed imminent, Friedrich took the initiative: he sent his brother Heinrich to the Russian capital St. Petersburg to persuade Catherine II to participate in an annexation of Polish territories. The empress was ready, and after some moral doubts, Maria Theresa also agreed in 1772. On August 5, 1772, the partition treaty was signed in Saint Petersburg . Russia, Prussia and Austria annexed large areas of Polish territory, Prussia got Polish Prussia, as Frederick wanted. Friedrich then had his text interpreted extensively in order to make his territorial gains in the network area as large as possible. In doing so, Prussia did not shy away from bribing Polish border inspectors. No objection was raised by the Western European great powers, the balance of power seemed to be preserved, since three states benefited from the illegal annexations and not just one. The historian Karl Otmar Freiherr von Aretin advocates the thesis that Prussia "finally rose to the rank of a major European power" through participation in the country robbery on an equal footing.

In the War of Bavarian Succession known (1778/1779), also known as "potato war", Friedrich thwarted the ambitions of the Habsburg Emperor Joseph II. , Belgium to exchange them for large parts of Bavaria. Without the intervention of Prussia, Bavaria would have become part of Austria with some probability. Despite its assistance pact, Russia did not intervene in this fourth war, which Frederick waged against the Austrians, because it did not see the alliance as a given. After all, Prussia was not attacked in its own country. An alliance treaty concluded between Austria and Russia in 1780 invalidated Frederick's alliance with Katharina, and Prussia threatened to be isolated. In 1785 Friedrich founded the Protestant-dominated Fürstenbund with which he hoped to thwart Austria's adherence to the Bavarian-Belgian exchange project. In the same year he concluded a friendship and trade treaty with the United States , the basis of which was the recognition by Prussia of the only recently independent 13 states of the United States . For ten years he had resisted the urge of the Americans to recognize their republic before the end of the war of independence . After the Peace of Paris , Prussia was the first state to sign a treaty with the United States. Friedrich himself was in correspondence with George Washington .

death

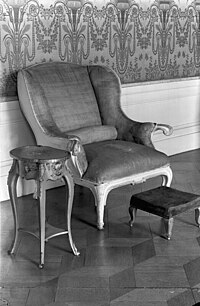

Friedrich died in his armchair on August 17, 1786 in Sanssouci Palace . Although he had a different order during his lifetime, his nephew and successor Friedrich Wilhelm II had him buried in the Potsdam Garrison Church in the crypt of the royal monument behind the altar next to his father Friedrich Wilhelm I.

After his victory over the Prussian army near Jena and Auerstedt on the march to Berlin on October 25, 1806, Napoleon Bonaparte visited Potsdam in the midst of his generals. His words, “You wouldn't have come this far if Friedrich was still alive”, were probably not - as is often claimed - at the royal grave in the garrison church, but in Friedrich's apartment in the Potsdam City Palace . Out of respect for the personality of Frederick the Great, Napoleon placed the garrison church under his personal protection.

In 1943 the coffins of the kings ended up in an air force bunker in Eiche , in March 1945 first in a mine near Bernterode , then due to the political explosiveness of the find - Bernterode was in the future Soviet zone - in the Marburg Castle . In February 1946, in a secret operation, they were brought to the Marburg State Archives, which at the time was the location of the Americans' first Central Collecting Point . On August 16, the sarcophagi were relocated to the local Elisabeth Church as part of the “Operation Bodysnatch” . On the initiative of Louis Ferdinand of Prussia , they came to the chapel of Hohenzollern Castle in 1952 .

On 17 August 1991, the last will was fulfilled the king and his coffin to Potsdam reburied to be buried on the terrace of Sanssouci in the still existing crypt. Friedrich had decreed in his will that he would be buried there at night with the smallest of entourage and by the light of a lantern. That corresponded to his philosophical claim. Instead, the funeral turned out to be a kind of state funeral. Since then, a simple stone slab has marked and adorned his grave .

Personality, network of relationships, preferences and works

Relationships

Friedrich corresponded with Voltaire , whom he met several times. In 1740 Voltaire was a guest at Rheinsberg Castle for 14 days . As in Rheinsberg, Friedrich surrounded himself at Sanssouci Palace with intellectual interlocutors who appeared at the round table in the evening. Guests were George Keith and his brother, the Marquis d'Argens , Count Algarotti , La Mettrie , Maupertuis , Count von Rothenburg , Christoph Ludwig von Stille , Karl Ludwig von Pöllnitz , Claude Étienne Darget and Voltaire. From 1751 Voltaire stayed in Potsdam for about two years. The ingenious picture puzzle attributed to Friedrich and Voltaire must come from this time . In 1753 a rift broke out, which caused displeasure for some time. After the reconciliation brokered by Wilhelmine von Bayreuth, Friedrich corresponded again with Voltaire from 1757. In 1775 he even sent him a portrait of himself.

Friedrich restricted close personal contacts largely to men; he lived separately from his wife since he ascended the throne. Various sources suggest that he was homosexual: As a young Crown Prince, he confided to Friedrich Wilhelm von Grumbkow that he was not attracted enough to women to be able to imagine entering into a marriage. On the eve of the Battle of Mollwitz, he recommended that his brother August Wilhelm, in the event of his death, “those whom I have loved most in life” - only the names of men followed, including that of his valet Michael Gabriel Fredersdorf . In 1746 he wrote a hateful letter to his brother Heinrich, who was openly gay, and was marked by jealousy for the "beautiful Marwitz", Heinrich's chamberlain, whom Friedrich claimed to be suffering from gonorrhea . Between 1747 and 1749 he wrote Le Palladion , a long poem that cheerfully described the homosexual adventures of his reader Darget. There were also many rumors, not least of which were contributed by Voltaire, Anton Friedrich Büsching and the doctor Johann Georg Zimmermann , who had treated Friedrich shortly before his death.

Whether Friedrich ever lived out his inclination physically is controversial: Reinhard Alings believes that Friedrich lived celibacy and was not able to have a real love affair after the traumatic experiences of his childhood. Even Frank-Lothar Kroll believes that Frederick investment was significantly less live decisive than his brother. Wolfgang Burgdorf, on the other hand, believes that the king did indeed live out the homosexuality that he later believed to be homosexual. This is one of his essential personality traits, which can be used to explain the central character traits of Friedrich: He was unable to fulfill his father's wish to father an heir to the throne and compensated for his failure with lust for glory and willingness to take military risks . For example, Kunisch calls contemporary statements about this “facet” of Friedrich's character “denunciatory” or “self-important”. At least in Friedrich's youth, heterosexual feelings and experiences can also be demonstrated, for example in relation to the ballet dancer Barbara Campanini . After all, it is also possible that Friedrich only staged his homosexuality, for example to hide an impotence .

Some of the few women who met his high standards and to whom he therefore paid his respect were the so-called "great Landgravine" Henriette Karoline von Pfalz-Zweibrücken and Catherine II of Russia , to whom he dedicated several poems and with whom he wrote a lot was standing. However, he has avoided Katharina's two-time invitations to face-to-face meetings; Friedrich never met Maria Theresa personally either. He expected women to have the same aesthetic spirit for which his round tables were praised.

The man of letters

Friedrich wrote numerous works, all in French. He himself was inescapably “possessed” by a passion, as he wrote, which he called “métromania”, as addiction to rhyme.

His Antimachiavel (1740) became famous all over Europe , in which he subjected Niccolò Machiavelli's state-political principles to a critical analysis committed to the spirit of the Enlightenment. In the Antimachiavel he also justified his position regarding the admissibility of the preventive strike and the "war of interests". According to this, the prince pursues the interests of his people in a "war of interests", which not only entitles him, but even obliges him to resort to violence if necessary. With this he anticipated the reasons for the conquest of Silesia in 1740 and the invasion of Saxony in 1756.

With the memorabilia on the history of the House of Brandenburg (1748), the history of my time (first draft 1746), the history of the Seven Years War (1764) and his memoirs (1775), he wrote the first comprehensive account of developments in Prussia. In it he not only justified his political views, but also strongly influenced his perception through later historiography.

For his work Ueber die deutsche Litteratur, published in German by Decker in Berlin in 1780 ; the shortcomings of which it can be blamed; the causes of the same; and the means to improve it (De la Littérature Allemande) , Friedrich received severe criticism in the German intellectual world. He had not noticed the upswing in German literature in the present and now recommended French literature as a model. On behalf of Friedrich's sister Philippine Charlotte von Prussia , Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Jerusalem published a critical answer anonymously, while Justus Möser and Johann Michael Afsprung wrote counter-writings.

Friedrich promoted the Royal German Society (Königsberg) .

The art admirer

Friedrich was interested in art in every form. He took care of the conception of his buildings, which give the Frederician Rococo its name as a style variant. Immediately after taking office, he had the Unter den Linden opera house built as a temple of the muses for the Berlin audience , sketched his Potsdam Sanssouci Palace and had it executed by Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff . After the end of the Seven Years' War, the New Palais was built in the monumental Baroque style in the west of the Sanssouci Palace Park. The buildings are often joined by statues of Apollo, Hercules and the Muses as sculptural decorations. He also put on important picture collections in Sanssouci and in the New Palais.

Especially in his younger years, Friedrich seems to have had a weakness for the gallant scenes in paintings by Antoine Watteau , Nicolas Lancret and Jean-Baptiste Pater , later he also acquired paintings from the Italian Renaissance and Baroque as well as Flemish and Dutch works. His taste in art was partly shaped by amateurism and personal hobby, while he paid little attention to recent developments in many areas. The acquisition of the antique bronze statue of the “Praying Boy”, which at the time was believed to be a representation of Antinous , the pleasure boy of Emperor Hadrian, is explained from the possession of Prince Eugene with the homoerotic taste of the Prussian King. The same applies to the statues of naked Mars and Mercury on the portal to the entrance hall in Sanssouci. Other rooms were decorated with erotic motifs and homoerotic depictions.

Friedrich was also very fond of music. He played the flute very well and composed at a high level , supported by his flute teacher Johann Joachim Quantz . Later he had a great fondness for the flute sonatas by Muzio Clementi (1752-1832). He wrote the libretto for the opera Montezuma , which was set to music by Carl Heinrich Graun . It is a legend that the Marcha Real , later the Spanish national anthem, was composed by Friedrich. There is also no evidence that he composed the Hohenfriedberger March . In contrast, he composed the Mollwitz March in 1741. Franz Benda and Johann Gottlieb Graun played important roles in the musical life of Rheinsberg and Berlin . Johann Sebastian Bach's appearance in the Potsdam City Palace on May 7, 1747, arranged by the court musician Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach , and the “Royal Theme” presented by Friedrich, led to its processing in Bach's famous collection The Musical Offering .

The Freemason

During a conversation at the table, on a trip to the Rhine in 1738, his father made derogatory comments about Freemasonry . Count Albrecht Wolfgang von Schaumburg-Lippe disagreed and openly professed Freemasonry. Friedrich was impressed and asked the Count to arrange for him to join the Freemasons' Union. Without his father's knowledge, Friedrich was deputies of the Loge d'Hambourg under conspiratorial conditions on the night of 14./15. Made a Freemason in Braunschweig on August 28, 1738 . The list of members leads to No. 31 the entry: "Friedrich von Preussen, born Jan. 24, 1712, Crown Prince". After his accession to the throne, he carried out Masonic work in the Charlottenburg Palace . His court box, however, was reserved for the aristocratic members.

The dog lover

The king's greatest passion is that which he cared for his dogs; He is quoted as saying: "Dogs have all the good qualities of humans without having their faults at the same time." His favorite bitches were the greyhounds Biche , Alcmène and Superbe. They slept in his bed and were fed by the king at table. In his last years Friedrich preferred the company of his dogs to that of his fellow men. In his will, he decreed that he would be buried next to his dogs in a crypt on the terrace of Sanssoucis Castle - a will that was only fulfilled in 1991.

reception

Portraits and monuments

A large number of portraits were made of Friedrich II during his lifetime . They were also very popular with his admirers abroad; he himself used to give them away in recognition of the services he had provided - whether as a life-size painting, as a miniature set in diamonds that was worn like a medal, or on a snuffbox . Since the beginning of their scientific research, opinions have diverged about the likeness of these portraits to life: In 1897, the art historian Paul Seidel complained that "a clear, unadulterated judgment [...] of what Frederick the Great looked like in reality" cannot be derived from the surviving portraits to win. In contrast, the historian Johannes Kunisch , in his biography of Friedrich, published in 2004, suspects that the portraits by name of the court painter Antoine Pesne "faithfully reproduce the characteristics of his appearance".

One reason for the doubts about the likeness of the portraits is that this was not at all the intention of the commissioners of images of the rulers of the 18th century: it was rather a matter of depicting the political and social role in which the portrayed wanted to present himself publicly , for example as a ruler with a scepter and an ermine cloak , as a competent military leader or as a humble, loyal father of the country. According to the art historian Frauke Mankartz, the recognizable “ brand ” was more important than the realism . Friedrich himself repeatedly scoffed at the fact that his portraits looked little like him. He also had a pronounced aversion to portraiture, which he consistently refused to do when he took office because he felt too ugly for it: you have to be Apollo , Mars or Adonis to be painted, and he has no resemblance to them Gentlemen, he wrote to d'Alembert in 1774 .

In fact, not a single portrait made during Friedrich's reign is beyond doubt authentic; that, as Jean Lulvès claimed in 1913, he sat as a model for the painter Johann Georg Ziesenis during a visit to Salzdahlum in 1763 , is denied. Like other portraitists, Ziesenis had to be content with sketches that they made after meeting the king. Only once in 1733, as Crown Prince, Friedrich is said to have sat as a model for a painter, Pesne, for several hours, and that only for the sake of his favorite sister Wilhelmine. All other portraits depicting Friedrich's appearance in middle years and in old age were not created during portrait sessions, but rather extrapolations of older portraits (e.g. von Pesne) or painted according to memory.

The art historian Saskia Hüneke identifies several types of Friedrich portraits, each with a high recognition value: On the one hand, the youthful image type, oriented towards the baroque ruler 's portrait, with softer facial shapes, such as the works of Pesnes and the profile portrait of Knobelsdorff from 1734 with their updates. Clearly different from this is the old age portrait type, which goes back to Daniel Chodowiecki's drawings and was further developed in the portraits of Johann Heinrich Christian Frankes from around 1764 and Anton Graff from 1781, which were created after the Seven Years' War . It shows the king as "Old Fritz", gaunt, serious, with sharp nasal folds, large eyes and a narrow mouth. The death mask and the portraits made after it can be understood as a continuation of this age type. The portrait of Ziesenis and a portrait bust of Bartolomeo Cavaceppi from 1770 formed a medium type.

- Portraits during Friedrich II's lifetime

Antoine Pesne , 1736

David Matthieu , 1740s

Johann Georg Ziesenis , 1763

Meno Haas after a drawing by Chodowiecki from 1777

In the 19th century the king became a popular subject in history paintings . The painter Adolph von Menzel depicted events from the life of Frederick the Great in many of his pictures, including the flute concert of Frederick the Great in Sanssouci and The Round Table of Sanssouci as the most famous works . Even Wilhelm Camphausen , Carl Röchling and Emil Hünten created historicizing representations which had the life of Frederick II. The subject, many of which were reproduced in books.

During his lifetime, Frederick II refused to be represented in monuments . The only exception was the obelisk erected in 1755 on the Old Market in Potsdam , on whose shaft four portrait medallions created by Knobelsdorf could be seen. They showed the Great Elector , King Friedrich I , Friedrich Wilhelm I and, as the completion of the dynastic line of ancestors, Friedrich II. After Friedrich's death, numerous monuments were erected to him. One of the first monumental monuments for Frederick the Great was created in 1792 in the park of Neuhardenberg Castle, based on a design by Johann Wilhelm Meil , which only shows the person who had just died six years earlier in a relatively inconspicuous portrait relief, which is allegorically mourned by Mars and Minerva. Stand-alone portraits and statues of persons are the bust in the Walhalla designed by Johann Gottfried Schadow in 1807 and the statue erected by Joseph Uphues in monument group 28 on Berlin's Siegesallee , which was particularly dear to Kaiser Wilhelm II . The first and most important monument erected in Berlin is the equestrian statue of Frederick the Great from 1851 on Unter den Linden . The memorial survived World War II without damage. In 1950 the SED had it removed in the course of the destruction of the city palace . The re-establishment happened in 1980, when the historical role of the king as an enlightened ruler was assessed more positively by the Marxist-Leninist interpretation of history. A scaled-down replica of the Berlin equestrian statue was in the amber room of the Catherine Palace in Tsarskoye Selo until 1917 . A replica of the equestrian monument (reduced in size and with a different base) is in Potsdam in Sanssouci Park south of the Orangery Palace , in the "New Piece" below the anniversary terrace.

Further monuments to Frederick the Great can be found in the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin-Mitte, at Charlottenburg Palace , in Volkspark Friedrichshain (restored in 2000), on the market square in Berlin-Friedrichshagen (restored in 2003) and in the Marlygarten of Sanssouci Park in Potsdam. The bronze copy at Charlottenburg Palace was created after photographs of the “lost original in marble” by Johann Gottfried Schadow for the Paradeplatz in Stettin. In the Sanssouci Palace in Potsdam there is a 91 centimeter statuette showing King Friedrich II with the greyhounds . It was cast in bronze by François Léquine in 1822, based on a model by Schadow from 1816. The statue on the plantation at the Garrison Church in Potsdam no longer exists . There is a memorial stone for Friedrich on the former “Knüppelweg” in Lieberose, Brandenburg . This almost forgotten memorial stone stands at the place where Friedrich gathered his troops after the defeat near Kunersdorf . One of the youngest Friedrichs monuments was built in 2012 (for the 300th birthday) in Wernigerode am Harz in historicizing forms and is there to commemorate the foundation of the “Friedrichsthal” colony.

- Monuments of Frederick II

Monument from 1792 in the Neuhardenberg Castle Park

Equestrian statue in the Amber Room , Tsarskoye Selo

Equestrian statue at the Orangery Palace , Potsdam

Still image in the Alte Nationalgalerie , Berlin

Statue at Charlottenburg Palace , Berlin

Monument in Volkspark Friedrichshain , Berlin

Statue on the market square in Berlin-Friedrichshagen

Still image in the Marlygarten , Potsdam

Statue at the Garrison Church , Potsdam

Badge from the iron foundry in Gleiwitz (1936)

Monument in Wernigerode from 2012

Contemporary namesake

As early as 1766, during his lifetime, the council of the Westphalian city of Herford asked for permission to name the municipal high school after the sovereign. The Friedrichs-Gymnasium Herford has since become the only school named after him. The occasion was a nationwide collection approved by Friedrich for the renovation and expansion of the school.

Political Myth

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the political myth surrounding Frederick the Great was subject to constant change. While "Old Fritz" was still considered the founder of German dualism until 1870 , later generations referred to him in a positive way. Many politicians and aristocrats of the late 19th and early 20th centuries tried to emulate him and stylized him as a pioneer of Protestant Germany. An example of this veneration are the Fridericus Rex films of the 1920s. Friedrich was one of the first celebrities whose biography was prepared for the medium of cinema, which was just emerging at the time.

The glorification of Friedrich reached its climax during the National Socialist era under the leadership of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels . Above all, the six films in which the then famous actor Otto Fee played the Prussian King played an important role. The Nazi propaganda not only described him as the “first National Socialist”, Friedrich and his followers were also stylized as the epitome of German discipline, steadfastness and loyalty to the fatherland. In the last months of the war, for example, the National Socialists justified calling the Hitler Youth to the Volkssturm on the grounds that Friedrich had also elevated 15-year-old aristocratic sons to lieutenants. The legend of the charismatic Prussian king was misused by political rulers for centuries; whether it was described as “un-German” or “German national” was subject to the respective zeitgeist.

The Mainz historian Karl Otmar von Aretin denies that Friedrich ruled in the manner of enlightened absolutism and sees him as the founder of an irresponsible and Machiavellian tradition in German foreign policy.

The Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation provided completely new insights into the life of Friedrich in the anniversary year 2012 (300th birthday of Frederick the Great) with its nationally sensational exhibition “Friederisiko” in the New Palais in Sanssouci.

ancestors

| Pedigree of King Friedrich II of Prussia 1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great-great-grandparents | Elector Georg Wilhelm (Brandenburg) (1595–1640) ⚭ 1616 Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate (1597–1660) |

Governor of the Netherlands Friedrich Heinrich (Orange) (1584–1647) ⚭ 1625 Amalie zu Solms-Braunfels (1602–1675) |

Elector |

Duke |

Marquis Alexander II Desmier d'Olbreuse ⚭ Jacquette Poussard de Vandré |

|||

| Great grandparents | Elector Friedrich Wilhelm (Brandenburg) (1620–1688) ⚭ 1646 Luise Henriette of Orange (1627–1667) |

Sophie von der Pfalz (1630–1714) |

Duke Georg Wilhelm (Braunschweig-Lüneburg) (1624–1705) ⚭ 1676 Eleonore d'Olbreuse (1639–1722) |

|||||

| Grandparents | King Friedrich I (Prussia) (1657–1713) ⚭ 1684 Sophie Charlotte of Hanover (1668–1705) |

King George I (Great Britain) (1660–1727) ⚭ 1682 Sophie Dorothea von Braunschweig-Lüneburg (1666–1726) |

||||||

| parents | King Friedrich Wilhelm I (Prussia) (1688–1740) ⚭ 1706 Sophie Dorothea of Hanover (1687–1757) |

|||||||

|

Friedrich II. (1712–1786), King of Prussia |

||||||||

1 The family tree of Frederick the Great shows the ancestral decline that is often found in high nobility circles . Since his parents were first cousins, as were his mother's parents, the number of his great-great-grandparents was reduced from 16 to 10.

factories

See also

Literature (selection)

Bibliographies

- Bibliography of Frederick the Great: 1786–1986. The literature of the German-speaking area and translations from foreign languages . Edited by Herzeleide (Henning) and Eckart Henning . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1988, ISBN 3-11-009921-7 .

- (Reinhard) B (reymayer): Philosophe de Sans-Souci, bibliographical references. In: Friedrich Christoph Oetinger: The school chart of the Princess Antonia. Edited by Reinhard Breymayer and Friedrich Häußermann. Part 2: Notes. Berlin / New York 1977 (Texts on the History of Pietism, Section VII, Vol. 1, Part 2), pp. 258–266 (75 titles mainly on the poetic work of Frederick the Great); see further references, ISBN 3-11-004130-8 , pp. 267-312.

- Burkhard Hegermann: Guide through the Friedrich anniversary literature. Berlin-historica Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-939929-14-7 .

- Bibliography of Frederick the Great. Supplements 1786–1986. New publications 1986–2013. Edited by Herzeleide Henning (= publications from the archives of Prussian cultural heritage. Work reports. Vol. 18). Self-published by the Secret State Archives PK, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-923579-25-9 .

Lexicon contributions

- Josef Johannes Schmid : Friedrich II., Elector of Brandenburg, King in (from 1777: of) Prussia. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 18, Bautz, Herzberg 2001, ISBN 3-88309-086-7 , Sp. 475-492.

- Otto Graf zu Stolberg-Wernigerode : Friedrich II. The great. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 5, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1961, ISBN 3-428-00186-9 , pp. 545-560 ( digitized version ).

- Leopold von Ranke : Friedrich II. (King of Prussia) . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1877, pp. 656-685. (outdated)

Biographies

Modern historical research

- Tillmann Bendikowski : Frederick the Great. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-570-01131-7 .

- Tim Blanning : Frederick the Great - King of Prussia - a biography. Translation from English Andreas Nohl. Beck, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-406-71832-8

- Jean-Paul Bled: Frederick the Great. Translated from the French by Wolfgang Hartung. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2006, ISBN 978-3-538-07218-3

- Jean-Paul Bled: Frédéric le Grand. Fayard, Paris 2004, ISBN 2-213-62086-5 .

- Wilhelm Bringmann: Frederick the Great. A portrait. Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8316-0630-7 .

- David Fraser: Frederick the Great. Penguin, London 2000, ISBN 0-14-028590-3 .

- Ewald Frie : Friedrich II. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2012, ISBN 978-3-499-50720-5 .

- Peter-Michael Hahn : Friedrich II of Prussia. General, autocrat and self-promoter . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-17-021360-9 (focus: reception history until 1989, against uncritical adoption of Friedrich's written statements about himself).

- Oswald Hauser (ed.): Friedrich the great in his time. Böhlau, Cologne 1987, ISBN 3-412-08186-8 .

- Gerd Heinrich : Friedrich II of Prussia. A great king's achievement and life. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-428-12978-2 . ( Review ).

- Georg Holmsten : Friedrich II. With personal testimonies and photo documents. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1969. (New edition: 2001).

- Christian Graf von Krockow : Frederick the Great. A picture of life. Bastei Lübbe, 2005, ISBN 3-404-61460-7 .

- Johannes Kunisch : Frederick the Great. The king and his time. 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-52209-2 .

- Johannes Kunisch: Friedrich the Great , CH Beck, Munich 2011 (deals primarily with the "statesman and general", domestic and foreign policy, less Friedrich's cultural activities).

- Jürgen Luh : The big one. Friedrich II of Prussia. Siedler, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-88680-984-4 .

- Ingrid Mittenzwei : Friedrich II of Prussia. A biography. VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1980.

- Theodor Schieder : Frederick the Great. A kingdom of contradictions. Ullstein Propylaeen Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-549-07638-X .

- Bernd Sösemann (Ed.): Frederick the Great in Europe - celebrated and controversial. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-515-10089-2 .

- Bernd Sösemann, Gregor Vogt-Spira (Ed.): Friedrich the Great in Europe. History of an eventful relationship. 2 volumes. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-515-09924-0 .

Exhibition catalogs

- Friedrich Benninghoven , Helmut Börsch-Supan , Iselin Gundermann: Friedrich the Great. Exhibition of the Secret State Archives of Prussian Cultural Heritage on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the death of King Frederick II of Prussia. 2nd revised edition. Nicolai, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-87584-172-7 .

- German Historical Museum (ed.): Friedrich the Great. adored. transfigured. Damn. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-515-10123-3 .

Popular science and essayistic monographs

- Rudolf Augstein : Prussia's Friedrich and the Germans. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1968.

- Jens Bisky : Our King: Frederick the Great and his time. A reading book. Rowohlt, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-87134-721-4 .

- Johannes Kunisch: Frederick the Great in his time. Essays. CH Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56282-2 .

- Ullrich Sachse (editor): Friederisko. Frederick the Great. The essays. Exhibition volume part I, Hirmer Verlag, Munich. 2012. ISBN 978-3-7774-4701-8 (volume of essays).

- Wolfgang Venohr : Fridericus Rex. Frederick the Great - Portrait of a Dual Nature. Gustav Lübbe Verlag, Bergisch Gladbach 2000, ISBN 3-7857-2026-2 .

Monographs relevant to the history of science

- Thomas Carlyle : Friedrich the Great , concerned and introduced by Karl Linnebach , 1910, Verlag Martin Warneck, Berlin

- Reinhold Koser : History of Frederick the Great. Fourth and fifth increased editions. (four volumes), Cotta'sche Buchhandlung Nachhaben, Stuttgart / Berlin, Vol. 1 1912, Vol. 2/3 1913, Vol. 4 1914.

- Franz Kugler , Adolph von Menzel : History of Frederick the Great. R. Löwit, Wiesbaden 1981. (New edition of the first print from 1840).

- Karl Heinrich Siegfried Rödenbeck : Diary or history calendar from Frederick the Great's regent life , 1840–1842.

Source collections for biography

- Hans Jessen (Ed.): Friedrich the Great and Maria Theresa in eyewitness reports. dtv, Munich / Frankfurt 1972.

- Jürgen Overhoff, Vanessa de Senarclens (ed.): To my mind. Frederick the Great in his poetry. An anthology , Schöningh, Paderborn 2011.

Studies on individual aspects

- Josef Johannes Schmid : Frederick the Great. The dictionary of persons . von Zabern, Darmstadt and others 2012, ISBN 978-3-8053-4367-1 .

family

- Johannes Bronisch: The fight for Crown Prince Friedrich. Wolff versus Voltaire. Landt Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-938844-23-6 .

- Christian Graf von Krockow : The Prussian Brothers. Prince Heinrich and Frederick the Great. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-421-05026-0 .

- Charlotte Pangels: Frederick the Great. Brother, friend and king. Callwey, Munich 1979.

- Heinz Ohff : Prussia's kings. Piper Verlag, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-492-31004-8 . (Pp. 85–144)

Culture

- James R. Gaines: Evening in the Palace of Reason. Bach meets Frederick the Great in the age of enlightement. Harper Perennial Books, London 2005, ISBN 0-00-715658-8 .

- Brunhilde Wehinger (ed.): Spirit and power. Frederick the Great in the context of European cultural history. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-05-004069-6 .

Politics, administration, military

- Frank Althoff: Studies on the balance of powers in the foreign policy of Frederick the Great after the Seven Years War (1763–1786). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-428-08597-3 .

- Heinz Duchhardt (ed.): Frederick the Great, Franconia and the Empire. Böhlau, Cologne 1986, ISBN 3-412-03886-5 .

-

Christopher Duffy : Frederick the Great. A military life , Routledge & Paul, London 1985.

- German: Frederick the Great. A soldier's life. Benziger, Zurich 1986. (New edition: Düsseldorf 2001, ISBN 3-491-96026-6 ).

- Christopher Duffy: The army of Frederick the Great. David & Charles, Newton Abbot 1974.

- Martin Fontius (Ed.): Friedrich II. And the European Enlightenment. Duncker & Humblot. Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-09641-X ( review ).

- Rüdiger Hachtmann : Friedrich II. Of Prussia and Freemasonry. In Historische Zeitschrift , 264, 1997, pp. 21-54.

- Walther Hubatsch : Frederick the Great and the Prussian Administration. Grote, Berlin 1973.

- Johannes Kunisch : The miracle of the House of Brandenburg. Studies on the relationship between cabinet politics and warfare in the age of the Seven Years' War. Oldenbourg, Munich 1978.

Web links

- Literature by and about Friedrich II in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Friedrich II in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Friedrich II. In the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Works by Friedrich II in the Gutenberg-DE project

- "Friedrich the Great" themed portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Digital edition of the works of Frederick the Great (French and German)

- Directory of works by and about Friedrich II. In the FII project of the Trier University Library available online

- Entry in the German Central Library for Economics

Remarks

- ↑ See Antimachiavel. In: œuvres. Vol. 8, p. 66, and Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire de la maison de Brandenbourg. In: Œuvres , vol. 1, p. 123.

- ↑ This and the following according to Johannes Kunisch: Friedrich der Große , Munich 2011, here: p. 8.

- ↑ Johannes Kunisch: Friedrich the Great , Munich 2011, p. 11.

- ↑ Angela Borgstedt : The Age of Enlightenment , Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2004, p. 21.

- ↑ Johannes Kunisch: Friedrich the Great , Munich 2011, p. 17.

- ↑ Johannes Kunisch: Friedrich the Great , Munich 2011, p. 19.

- ↑ The namesake were David Splittgerber (1683–1764) and Gottfried Adolph Daum (1679–1743).

- ↑ Hans Eberhard Mayer : Siblings of the same name in the Middle Ages. In: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 89 (2007), pp. 1–17, here: p. 15.

- ↑ Regulations on how my eldest son Friedrich should keep his studies ... September 3, 1721, quoted from: Frank Schumann (Ed.): Most gracious father. Berlin 1983, pp. 23-25.

- ↑ Jürgen Overhoff, Vanessa de Senarclens (ed.): To my spirit. Frederick the Great in his poetry. An anthology , Schöningh, Paderborn 2011, p. 13.

- ↑ Heinz Duchhardt (Ed.): Friedrich the Great, Franconia and the Empire. Böhlau, Cologne 1986, ISBN 3-412-03886-5 , p. 9.

- ↑ Florian Kühnel: Sick honor ?: Noble suicide in the transition to modernity, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2013, p. 137

- ^ Wording from Theodor Fontane , Walks through the Mark Brandenburg , Volume 2 Das Oderland, "Jenseits der Oder" - Küstrin: The court martial in Köpenick. http://www.zeno.org/nid/20004778146

- ↑ Johannes Kunisch : Frederick the Great - the King and his time. 5th edition. Beck, Munich 2005, pp. 40, 43.

- ^ Instruction from the king to Court Marshal [Gerhard Heinrich] von Wolden from August 21, 1731 ( online )

- ↑ Theodor Fontane wrote about this in the walks through the Mark Brandenburg : Volume 2 ( Oderland ) “Jenseits der Oder” - Tamsel I: Frau von Wreech; Volume 1 ( The County of Ruppin ) "Am Ruppiner See" - Neu-Ruppin: Crown Prince Friedrich in Ruppin.

- ↑ Hans-Henning Grote: Wolfenbüttel Castle. Residence of the Dukes of Braunschweig and Lüneburg. 2005, ISBN 3-937664-32-7 , p. 228.

- ↑ Joachim Campe: Love others. Homosexuality in German Literature . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1988, p. 110 f .; Johannes Kunisch: Frederick the Great. The king and his time . Beck Verlag, Munich 2004, p. 79.

- ↑ Reinhard Alings: “Don't Ask, Don't Tell” - was Friedrich gay? In: General Directorate of the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg (ed.): Friederisiko. Frederick the Great. The exhibition. Munich 2012, pp. 238–247.

- ↑ To life in Rheinsberg Jürgen Luh: The big one. Friedrich II of Prussia. Siedler, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-88680-984-4 , p. 136 ff.

- ↑ On the factual "banishment" of Elisabeth see also Schieder, Friedrich der Große, p. 51; as well as Karin Feuerstein-Praßer, Die Prussischen Königinnen, p. 197 ff.

- ↑ Ingrid Mittenzwei: Friedrich II. Of Prussia. A biography. Pahl-Rugenstein, Cologne 1980, ISBN 3-7609-0512-9 , p. 41 f., There also the objections of the counselors.

- ↑ For this see Mathias Schmoeckel: Humanität und Staatsraison. The abolition of torture in Europe and the development of common criminal procedure and evidence law since the high Middle Ages . Böhlau, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-412-09799-3 , entire wording in: Royal Academy of Sciences (ed.): Acta Borussica. Monuments of the Prussian State Administration in the 18th Century , Volume 6/2, Berlin 1901, p. 8.

- ↑ Koser (see list of literature), first volume, p. 196 f., Reference: fourth volume, p. 33.

- ↑ Michael Sachs: 'Prince Bishop and Vagabond'. The story of a friendship between the Prince-Bishop of Breslau Heinrich Förster (1799–1881) and the writer and actor Karl von Holtei (1798–1880). Edited textually based on the original Holteis manuscript. In: Medical historical messages. Journal for the history of science and specialist prose research. Volume 35, 2016 (2018), pp. 223–291, here: p. 275.

- ↑ "A Cologne vivait un fripier de nouvelles, / Singe de l'Aretin, grand faiseur de libelles, / Sa plume ètait vendue es se écrite mordants / Lançaient contre Louis leurs traits impertinents". Quoted from Ludwig Salomon: History of the German newspaper system. First volume. S. 147 ff., Oldenburg, Leipzig 1906.

- ^ Wolfgang Neugebauer : Prussia and Europe under Friedrich Wilhelm I and Friedrich II up to the middle of the 18th century. In: Ders. (Ed.): Handbook of Prussian History. Vol. 1: The 17th and 18th centuries and major themes in the history of Prussia. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009 ISBN 978-3-11-021662-2 , pp. 315 and 332 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ For the epithet "the great" see the conference report by Ullrich Sachse: Friedrich und die historical Größe . In: H-Soz-u-Kult , December 2, 2009.

- ↑ Illustration by Heinrich Wilhelm Teichgräber: Friedrich the Great, during the Battle of Torgau ( digitized version )

- ↑ Illustration by Heinrich Wilhelm Teichgräber: Friedrich the Great, after the battle of Kunersdorf . ( Digitized version )

- ↑ See Politische Correspondenz , Vol. 15, p. 308.

- ↑ Klaus Wiegrefe : The Little King. In: Der Spiegel 45/2011, pp. 75, 82 ( online ); Selma Stern : The Prussian State and the Jews. Volume 3: The time of Frederick the Great. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1971, ISBN 3-16-831372-6 , pp. 241, 249.

- ↑ letter 11,335th au ministre d'Etat comte de Finckenstein à Berlin in the digital edition of the University Library Trier .

- ↑ See Venohr, König , p. 209.

- ↑ letter 11,393th au prince Henri de Prusse in the digital edition of the University Library Trier .

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler : History of the West. From the beginnings in antiquity to the 20th century. Munich 2011, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Katja Frehland-Wildeboer: Loyal friends? The Alliance in Europe 1714–1914 . Oldenbourg, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-59652-6 , p. 115 f. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Norman Davies : In the Heart of Europe. History of Poland. Fourth revised edition. Beck, Munich 2006, p. 280.

- ↑ Wolfgang Neugebauer: Prussia and the European politics of power from the Seven Years War to the Princes' League. In: Ders. (Ed.): Handbook of Prussian History. Vol. 1: The 17th and 18th centuries and major themes in the history of Prussia. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009 ISBN 978-3-11-021662-2 , p. 343 f. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Karl Otmar Freiherr von Aretin: Exchange, division and country chatters as consequences of the equilibrium system of the European great powers. The Polish partitions as a European fate. In: Yearbook for the history of Central and Eastern Germany. 30, 1981, pp. 53-68, here: p. 56.

- ↑ Katja Frehland-Wildeboer: Loyal friends? The Alliance in Europe 1714–1914. Oldenbourg, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-59652-6 , pp. 118 f. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online).