Image of rulers

Images of rulers represent an individual who is at the head of a state. They define the person of the ruler as the official, as the bearer of a divine mission, and they can aim at the confirmation of a claim to power.

It is the function of the image to visually convey the position and meaning of the respective ruler or his affiliation to a dynasty . In the absence of the ruler, the image can be used as a representative; the image then deserves the same honor as the ruler himself. The image can contain a desire to be immortalized and aim to anchor a certain, authorized image in the memory of posterity.

The type of representation changes in the course of history, but the recognizability of the claim to power remains constant, which is visualized using symbols of power or symbols for divine legitimation . Individual traits of the person are not the goal of the representation, they recede in favor of an idealization and have only been given greater consideration since the Middle Ages.

The rulers are depicted standing, sitting on the throne, since the model of Marc Aurel as an equestrian statue and as a bust, in profile on coins or, in modern times, on postage stamps. As a rule, they are equipped with their insignia of power and office .

Images of rulers should show the person portrayed in a certain way, be it to idealize their appearance, to bring a positive “image” to the current recipient or posterity or to convey a certain political message. As Peter Burke puts it, the genesis of a rulership portrait is “a process in which the artist and the model became, so to speak, accomplices”.

to form

Images of rulers are available as paintings or sculptures, which in turn can be subdivided into different categories:

- Portrait (head shot)

- bust

- Half figure, full figure, seated figure (throne)

- Group picture , family picture

- Equestrian portrait, equestrian statue

- Example from ancient times

Emperor Augustus

Augustus on a Roman denarius , head shot

Augustus with citizen's crown , bust

Augustus of Primaporta , barefoot according to ancient statues of gods, with breastplate and paludamentum , full figure

- Example from modern times

King Charles IV of Spain

Charles IV with antique laurel wreath, coin

Goya : Family of Charles IV, 1800/01

iconography

The poses and gestures of a ruler follow certain social or art-historical conventions, as does the choice of background and accessories , which often become carriers of symbolic meanings.

Typical accessories include the sovereign insignia crown, scepter, globe and ceremonial sword , the regalia , the throne, the honorary canopy, which over time changes into the red curtain of honor, in front of which kings and rulers pose. Columns symbolize strength, Roman antiquities or temple or triumphal arch-like architecture establish a connection with Rome , idyllic panoramic landscapes indicate the flourishing and prospering of the ruled country, through the addition of allegorical figures , properties, virtues and achievements of the presented can be alluded to. to his wisdom and righteousness, to wealth and abundance, to unity and peace, to victories over cities and peoples. Augustus of Prima Porta is z. B. accompanied by Eros , possibly as an allusion to Venus , from which the Julier should descend. His tank shows a number of Olympic gods as well as personifications of subject or tribute peoples. On Philippe de Champaigne's portrait of Louis XIII. After the victory at La Rochelle , the king is crowned with laurel by Victoria, the goddess of victory .

The ruler on horseback indicates his ability to curb violence and rule a country with a skilled hand.

- Examples

Constantius II with a laurel wreath and scepter on a throne with a curtain of honor, scattering coins, AD 345

State portrait of Henry VIII without rulership insignia in

front of a triumphal arch architectureCharles V after the battle of Mühlberg , in the background an idyllic, peaceful landscape

Louis XIII is crowned by the goddess of victory Victoria after winning the battle

Mohammad Reza and Farah Pahlavi , dynasty picture, 1967; official photo

history

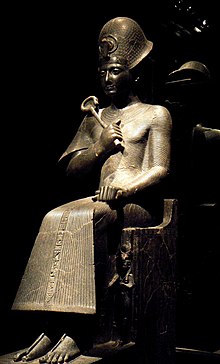

Mesopotamia, Egypt

Images of rulers from Sumer and Egypt have been around since the 4th – 3rd centuries. Preserved millennium before Christ. An early Sumerian example is the stele of Naram-Sîn / Suen from the 3rd millennium BC. The king, who is taller than his defeated enemies, wears a crown of horns , which is a sign of supernatural power and which in the ancient East was only available to the gods. Gudea statues , which represent the city prince of the Sumerian city of Lagaš , have survived in large numbers . Gudea is shown standing or sitting, in the pose of a person praying and with a disproportionately large head, either bald or with a crown-like headdress. These statues were commissioned by Gudea himself and represented the ruler in the temples he had built and which are occasionally listed on the sculpture.

In Hittite art, kings are depicted in full plastic form both on bas-relief and in full height. The king wears either his official costume such as cloak and scepter or bow and lance, sword and a pointed or dome-shaped cap.

In Egypt , statues of kings have been around since around 3000 BC. Manufactured. The first life-size statue of a pharaoh comes from the Serdab of the Djoser pyramid . King Djoser is enthroned on an armchair, he wears a mighty wig with a Nemes headscarf , a ceremonial beard and a scepter in his right hand. Two holes in the burial chamber gave the pharaoh a view of the courtyard to observe the rituals performed for him . Statues of kings in mortuary temples initially served the continued life of the king in the realm of the dead. Since the Middle Kingdom , images of rulers can also be found as a representation of royal power in temples of the gods and since the New Kingdom as colossal statues in front of pylons . The king is equipped with insignia of power or signs of religious symbolism, such as an animal tail, phallus pouch , crook , scepter, scourge , Nemes headscarf, uraeus snake on the headscarf, red or white crown or double crown .

Antiquity

In classical Greece, statues and busts of people who had earned themselves for the polis or had distinguished themselves through sporting achievements were occasionally erected, but honors with life-size statues were usually reserved for the gods .

Coins which Philip II of Macedonia had minted and which show the profile of the Olympian gods Athena, Apollo, Zeus or Hercules on the retro side and often attributes of the gods on the reverse side were exemplary and style-defining for coinage in general . Alexander the Great had coins with the image of Athena , under whose personal protection he saw himself , minted , which developed into the key currency in the entire area and were imitated as far as Central and Northern Europe. After his death the die cutters equipped the images of the gods with Alexander's features more and more clearly. Coins from the time of the Diadochi often show the profile of the respective ruler along with his name.

During Hellenism, the custom of honoring rulers and other people by placing statues in public spaces increased. If kingdoms and city-states were integrated, the setting up of portraits of rulers was accompanied by rituals in which they were given "godlike honors" ( isotheoi timai ).

- see also

Byzantium

In Byzantine art , the ruler is placed in a religious context. In the tradition of Byzantine image programs, the emperor is interpreted as an image of God in connection with the heavenly hierarchy. Coins often show the image of Christ on the reverse side and the head of the respective emperor on the retro side, who, like Christ, is depicted frontally on the obverse. In Byzantium, images of the emperor are usually produced in a standardized and idealized form and, in addition to illumination and via coins, they are also used on seals of bulls , on shields of higher military personnel or on the tablion of chlamys . They thus serve to represent the imperial power and its memoria .

Outstanding, but rare for Byzantium examples of emperors are the larger than life mosaics of Theodora and Justinian in the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, ie in the western and less image-hostile part of the Eastern Roman Empire.

The ritual, established in Rome since the end of the 3rd century, of sending images of emperors on the occasion of the appointment of emperors and co-emperors to provinces and cities of the empire, was also adopted by Byzantium. The riding bowl from Kerch found in 1891 shows Emperor Constantius II as a triumphant on horseback. Up until the 8th century, images of the emperor were sent from Byzantium to Rome and to rulers at the Franconian and Germanic courts. According to sources from the Council of Nicaea , these images were encaustic tablets.

middle Ages

In the Carolingian and Ottonian times, images of rulers can be found primarily in book illumination . Typical representations are the ruler enthroned under a canopy or in a mandorla , the ruler who receives homage from tributary tribes , the dynasty image , the dedication image and the coronation performed by Christ. This originally Byzantine motif spread to the west in the time of the Ottonians. This type of picture depicts a high point of theocratic kingship. It visualizes the highest possible legitimation of imperial rule given by God, and at the same time it presents the emperor as a servant of God ( servus dei ). Dedication pictures document the delivery of a precious, mostly liturgical codex by the representative of a monastery, which in turn has received generous gifts from the ruler and remains connected to him through prayers. Since the conflict between Henry IV and Gregory VII , the type of dedication image shaped by a Christocentric understanding has gradually disappeared.

The images contained in the codes were only accessible to a small number of selected people. The images on seals and coins , the iconography of which usually follows ancient models, found a wider distribution of the image of the ruler .

Modern times

Images of rulers also serve the client's memory in modern times , but are also used for diplomatic purposes. Since the invention of letterpress printing and the easier production of prints, the range of images of rulers has been expanded. Larger sections of the population can now get to know the "picture", the "image" of their sovereign and his family, as the respective client wishes. These pictures were distributed as leaflets , like Dürer's portrait of Emperor Maximilian , which was produced in large numbers and repeatedly reproduced. Many a sovereign had Martin Luther's translation of the Bible equipped with his portrait as a frontispiece , which, in addition to increasing his popularity, also promoted his sacralization.

Renaissance, baroque

Since the Italian Renaissance , medals have been added to the usual portraits of rulers on coins and seals . Unlike coins, medals are not based on sovereign rights , they do not seal any laws or official pronouncements, and can be reproduced in large numbers without problems, which makes them popular diplomatic gifts. Medals are embedded in the foundation stones of buildings so that “these things will be found once”, as Filarete writes in his architectural treatise “... and then we are remembered and our names are called ...” The medals reached their first artistic climax of the Pisan Pisanello with his portraits. Medals, which quickly became extremely popular among rulers in Italy, could only prevail north of the Alps around 80 years later. In contrast to the flat and small-format coins, the larger and thicker medals offer the artist better opportunities to work out portrait similarities in relief more precisely. The reverse of the medals is provided with allegories or reminds of a significant event from the reign of the sitter.

- Medals and seals

John VIII Palaeologos , medal by Pisanello , 1438

Franz I , medal from Benvenuto Cellini

Double portrait of Karl V and Ferdinand V on a medal by Peter Flötner

Elizabeth I on horseback; Seal of Nicholas Hilliard from 1586

The first free-standing, larger-than-life equestrian statues were created since antiquity, initially for the two Condottieri Gattamelata (1447) and Bartolomeo Colleoni (1496), which were followed by the equestrian statues of Italian city princes, erected in politically important places in their territory. In 1595 the equestrian statue of Cosimo I was erected in Florence on the Piazza della Signoria, while Leonardo's ambitious project of a colossal equestrian stutue for Francesco Sforza (1482/1499) did not get beyond the preparatory phase. The ruler on horseback also became a standard formula in painting, which was varied many times until the 19th century.

absolutism

The best-known image of the ruler of absolutism is probably the portrait of Louis XIV by Hyacinthe Rigaud . It shows Louis XIV as ruler removed from the people with all the insignia of power.

The crown on the pillow symbolizes his royal dignity, the marshal's baton is a symbol of the supreme warlord, the sword is a symbol of justice and jurisdiction. He is dressed in a blue cloak, which is lined with ermine fur , which was only permitted to ruling princes, and which is embroidered with the lilies of the House of Bourbon . Ludwig is positioned in front of a mighty pillar, which is a symbol of the stability and strength of his rule. He stands under an opulent red curtain. Such honorary canopies can already be seen on Byzantine representations and identify the ruler as an apparition of God who brought help.

19th century

In the 19th century, after the revolutions that changed the dominant balance of power, new elements moved into the image of the ruler. Rule is no longer authenticated by descent, divine right and pure power, but requires the public consent of the ruled, whose perspective can differ from the ruler's perspective. Images of rulers become more ambiguous, as they should correspond to the ambiguous wishes and diverse expectations that are brought towards the rulers, and which are therefore more "open to meaning" [hill].

The painters and sculptors use the means of history - genre painting . The image of the ruler becomes anecdotal with the aim of creating a certain "ruler image". The core of the image is the “ruler with a human face”.

Still images are often set on the initiative of citizens and financed by public collections. Exemplary here are the countless monuments and equestrian statues of Wilhelm I or II , some of which, like the so-called Wilhelmstürme, are financed by student or municipal collection campaigns and which set striking political accents across the entire area of the German Reich . The overflowing lust of the century in the setting of monuments subsequently became a popular topic for caricaturists.

However, state portraits with the representative and canonical representation of the respective ruler are still commissioned. They are usually made for a specific occasion, such as an accession to the throne, or for a specific location. State portraits remain the most important official form of portrait.

20th century

From the late 19th century to the present day, the traditional media, with which the image of the representative of state power was propagated over the centuries, only played a subordinate role. There are, however, a few striking examples of how painters have solved the problem of portraits of rulers in the present. Lucian Freud's small-format and unflattering portrait of the British Queen Elizabeth II is cropped as a closeup on both sides and at the crown and has generated outraged reviews in the English press. Jörg Immendorff put a gold-colored en face portrait of Chancellor Gerhard Schröder , which is fitted into a mandorla made of white-veined black marble, in a passepartout on which the usual ingredients of a ruler's portrait - eagle, lion, hunting dog, laurel branches, antique plinths - are shadowy. frolic as quotes from the treasure trove of art history. Both artists solved the problem with irony.

The preferred media, with which the rulers bring their self- image , their desired image , to the audience, are now posters, photography and film. The film Triumph des Willens by Leni Riefenstahl is an example of the staging and an almost sacral exaggeration of a ruler with all the subtle artistic means available to a film director .

However, even in the new media, the forms that have emerged in the course of art history remain relatively constant and constantly varied, while visual artists themselves hardly play a role. States with a monarchical constitution, states with a restorative tendency and states that lack democratic legitimacy still hold on to traditional forms of the image of rulers up to the present day. Bronze equestrian statues of General Franco were erected until the middle of the 20th century.

As a result of revolutions and political upheavals, the overthrow of monuments to rulers is one of the typical high-profile actions. Either the overthrow of the icon is initiated by the new rulers or it is carried out spontaneously by citizens. Most of the many monuments in the former Eastern Bloc have disappeared without a trace, on the other hand there are also isolated signs of a revival, such as the installation of a Stalin memorial in 2013 in the Siberian city of Irkutsk .

An outstanding example of a contemporary ruler is the Mao image on Tian'anmen Square . Mounted above the Gate of Heavenly Peace in Beijing, it shows the monumental size of the portrait of Mao who proclaimed China's independence on October 1, 1949. The iconic image is considered to be the most widely reproduced image of a person in the world.

Cartoons

Caricature is a form of criticism of the ruler and of the canonized portrait of a ruler . Typical for the caricature is a simplification of the forms and an exaggeration of the physiognomy or the elements of the constitution , which do not correspond to the ideal of beauty of the respective time.

There are early caricatures by Gian Lorenzo Bernini , who introduced the term Caricatura in France in 1665, or by Annibale Carracci . Bernini has Pope Innocent XI. caricatures how he - with his miter on his head - holding an audience in bed. Before the French Revolution , however, caricatures of rulers are extremely rare because of the risk to the artist of lese majesty .

Political caricature flourished in France from 1830 onwards with the founding of the magazines La Caricature (1830–35) and Le Charivari , both published by Charles Philipon . As a draftsman for Philipon worked u. a. Grandville and Daumier . Philipon's satirical magazines, with King Louis Philippe's preferred target in the shape of a pear, became the model and model for all of Europe.

Preferred media and techniques for caricature are drawings, prints , photomontages, and posters . Outstanding examples of political caricature and caustic criticism of the rulers are the photo montages by John Heartfield about Hitler , which were published in the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung in Berlin from 1930 and in Prague from 1938.

Web links

- Image of the ruler and face of the times in the republic and Roman imperial times. at viamus.uni-goettingen.de

- Image of rulers. In: Academic dictionaries and encyclopedias.

- The image of the ruler on coins of late antiquity.

- Images in history and politics. Images of rulers in the Federal Agency for Civic Education

literature

- Peter Burke : eyewitness . Pictures as a historical source. Wagenbach, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-8031-2631-3 .

- Dietrich Erben: Monument. In: Uwe Fleckner, Martin Warnke, Hendrik Ziegler (eds.): Handbook of political iconography. Volume 1, Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-57765-9 , pp. 235-243.

- Andreas Köstler, Ernst Seidl: Portrait and Image. The portrait between intention and reception . Böhlau, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-412-02698-0 .

- Rainer Schoch : The image of rulers in 19th century painting . (= Studies on 19th Century Art. 23). Prestel, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-7913-0052-0 .

- Percy E. Schramm : The German emperors and kings in pictures of their time. 751-1190. Edited by Florentine Mütherich. Munich 1983.

- Martin Warnke : Portrait of a ruler. In: Uwe Fleckner, Martin Warnke, Hendrik Ziegler (eds.): Handbook of political iconography. Volume 1, Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-57765-9 , pp. 481-490.

- Philipp Zitzlsperger: Gianlorenzo Bernini. The portraits of the pope and rulers . Hirmer, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-7774-9240-X .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Martin Warnke: Portrait of a ruler. In: Handbook of Political Iconography. Volume 1, Munich 2011, p. 481.

- ^ Warnke: Portrait of the ruler. 2011, p. 483.

- ↑ Peter Burke: Eyewitness. Berlin 2010, p. 29.

- ↑ Figure

- ↑ Jürg Eggler: Crown of Horns

- ↑ Seated Statue of Gudea, The Metropolitan Museum of Art .

- ↑ Ursula Kampmann: The coins of Alexander III. the great of Macedonia.

- ↑ Klaus Maria Girardet: The Emperor and his God. Berlin 2010, p. 108.

- ↑ Lexicon of the Middle Ages. Volume 1, Munich / Zurich 1989.

- ^ Claudia List, Wilhelm Blum: Subject dictionary on the art of the Middle Ages. Stuttgart 1996, p. 175.

- ↑ Wolfgang Eric Wagner: The liturgical presence of the absent king. Brill Academic Publ., 2010.

- ↑ Egon Boshof: Kingship and rule in the 10th and 11th centuries. 3. Edition. 2010, p. 115.

- ^ Warnke: Portrait of the ruler. 2011, p. 485.

- ↑ quoted from: Beverly Louise Brown: The portrait art at the courts of Italy. In: Keith Christiansen, Stefan Weppelmann (ed.): Faces of the Renaissance. Hirmer, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-7774-3581-7 .

- ↑ Hans Otto Hügel: Praise of the Mainstream: on the Concept and History of Entertainment and Popular Culture. Cologne 2007, pp. 156–167.

- ↑ Bernd Roeck : The historical eye: works of art as witnesses of their time. Göttingen 2004.

- ↑ Portrait of Queen Elizabeth II by Lucian Freud (2001). In: The Telegraph.

- ^ Günter Bannas: Schröder portrait. The hanging of the chancellor. In: FAZ.net

- ↑ Russia: New Stalin monument unveiled in Siberia. In: Spiegel-online. May 8, 2013.

- ↑ Roland Kanz: Caricature. In: Encyclopedia of Modern Times.

- ↑ J. Heartfield: The sense of the Hitler salute. Image.

- ↑ Tanja Wesselowski: Caricature. In: Handbook of Political Iconography. Volume 2, Munich 2011, pp. 44–56.