Roman imperial portraits

As a Roman emperor portraits portraits of be Emperor of the Roman Empire called. They were often artistic masterpieces, but were rarely created for purely artistic reasons, but rather as an important means of imperial self-expression. Apart from their artistic value, they are still important today as a source of self-image and reception of the Roman emperors.

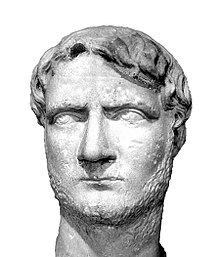

The portrait of Augustus

The first line of dynastic portraits begins with the portraits of the Emperor Augustus , initially that of the Julio-Claudian dynasty .

As is customary with many great figures in history, a number of portraits were also made of the first emperor of Rome. We have received no contemporary accounts of how he selected the form of these portraits intended for the public or the artists responsible for them. But it is certain that Augustus acted very carefully when it came to presenting himself to the people.

The earliest portraits of Octavian appeared on coins dating from 43 BC. Were minted. With this money, which he received after the murder of Gaius Julius Caesar in 44 BC. A mercenary army devoted to him was paid for, and the portrait on the coins was to remind them of the loyalty they owed their financiers. In these portraits he had a short beard, which was perhaps worn as a sign of mourning. In addition to the beard, the inscription on the edge of the coin also referred to the connection with the murdered Caesar.

When the conflict with Mark Antony broke out openly, the portrait of Augustus also changed. While only coins of the Octavian type with a beard have survived, we have some round sculptures of the following types, which can be basically divided into three different types of portraits, with the distinguishing features of the different hairstyles:

- Octavian type (or earlier: "Actium type")

- Prima porta type

- Forbes type

1. Octavian type

The term "Octavian type", like all names for portrait types, is modern and is intended to express that the portraits of this type do not yet mean Augustus, but rather Octavian in the period before January 16, 27 BC. Chr.

His hair seems to be whipped by the wind, his face suggests tension and energy, his head is turned to the right and he is looking up. This type stands in the tradition of the Hellenistic-Greek king portraits.

Hair design: Directly above the center of the forehead there are three strands of hair that are swept to the left when viewed from the viewer. They are finished off on either side by opposing curls. This creates a pincer motif on the left and a fork motif on the right.

2. Prima porta type

This is named after the famous tank statue of Augustus von Primaporta , a marble statue after a bronze original, dated after 20 BC. Chr.

In 27 BC Octavian submitted a new constitution. In the same year he received the title Augustus from the Senate. Now of course he had to be represented as the first citizen of the republic, which he pretended to have restored, for which a portrait in the tradition of royal portraits was certainly not useful. Augustus now chose an image based on the polycletic ideal, that is, the shape of the statue was idealized. His body took on heroic and perfect features, the head looked calmly forward and the violently moved hair froze.

Hair design: The same as in the Octavian type, only that the three central strands have become a single one. The pincer and fork motif were retained.

The prima porta type is the main type that was exported throughout the empire. (We have preserved over 250 portraits of this type and the other two.) It was used with minor variations until the death of Augustus in AD 14.

3. Forbes type

This type is named after a head in a private collection. It is a secondary type, i.e. a type that was used alongside the main type (the prima porta type), but not as frequently as this.

Hair design: Three uniformly arranged curls are seen from the viewer over the left half of the forehead. The hair above the right half of the forehead is swept to the left. As a result, the pliers and fork motif was dispensed with.

This type of portrait is also documented in the Ara Pacis (donated 13 BC), so it must have been before 9 BC. BC, the year the Peace Altar was consecrated.

Images of Augustus were produced and distributed over a very long period of time, starting with the coin images until after his death, because there were also posthumous portraits of Augustus.

There are no age portraits of Augustus; apparently there was no interest in showing age.

The development of the Roman imperial portrait in the crisis of the 3rd century

The 3rd century is considered to be the age of the great crisis of the Roman Empire (see Imperial Crisis of the 3rd Century ). In terms of art history, too, this epoch is one of the difficult ones in archaeological research, as the unstable circumstances make it very difficult to trace a clear line in the form of development. Furthermore, the process of change of this time is difficult to grasp, as there are only a few datable monuments. The portraits of the soldier emperors should be mentioned as a class of monuments that can be reliably dated ; The style change from the 2nd to the 3rd century was ultimately shaped by external influences, social restructuring, rule by the military and internal insecurity. More than 60 emperors came to power in a single century, often only for a few days, and few died of natural causes.

General characteristics of the portraits of soldiers and emperors of this time

In the development of the art style of this politically unstable period, realism , expressionism and an abstract form are expressed.

In the beginning, the suspicious, sharp look and facial features furrowed and suffering from worries about the state dominate. The typical physiognomy of a soldier emperor is characterized by the close-cropped hairstyle: the hair is only indicated by superficial incisions and processing with a chisel. Furthermore, these portraits are characterized by particularly hard and rough facial features. In the portraits of the emperors, one can observe a gradual solidification of the individual face shapes , in short: an abstraction of the forms.

With the Emperor Gallienus , however, the feeling of a new spirituality is conveyed. His restoration policy and return to ancient Roman values are reflected in his portrait. Over time, the strict and concerned facial features give way to a developing stereometrization: the wrinkles no longer go deep, the skin and the physiognomy appear frozen and petrified. In later times the gaze is no longer suspicious, but seems to wander into the distance.

Some portraits of the emperors - a closer look

The change in style from the 2nd to 3rd century starts with Septimius Severus (193-211) with the Prince portraits the curls ending Antonines and the definition drilling of the hair mass. The "Antonine Baroque" of the 2nd century is characterized by the fact that the hair is sculptured by drilling, whereby the resulting light and shadow effects give the appearance of an optical illusion. A kind of flicker effect was achieved on the hair using a hammer, chisel or drill. This contrasts with the hair design of the emperor portraits of the 3rd century: here the outline of the hair mass is closed and almost like a wig. In the third type of portrait of his portraits, Septimius Severus even identified himself with Sarapis by having himself depicted with the typical three to four twisted Sarapi curls over his forehead and parted beard.

The portraits of the elderly differ very much from portraits of young people: The portraits of the child emperors Elagabal , Severus Alexander , and Philippus Caesar are much smoother and make a far more youthful impression than comparable portraits in the 2nd century. The facial expressions of the portraits of older people often appear worried and appear suffering and pensive.

The emperors follow the tradition of the bearded Caracalla , they often appear unshaven or have a stubbly beard typical of this era - often only indicated by incisions. The soldier emperors - with the exception of Gallienus - wear short military haircuts.

Elagabal and Severus Alexander emphasize their foreign facial features and physiognomies: full lips and cheeks, tight eyebrows and a large nose characterize their Syrian origins. Severus Alexander is depicted in a portrait type as a young ruler of various ages with his portraits.

The portraits of the soldier emperors

The first soldier emperor Maximinus Thrax came to power after the assassination of his predecessor Severus Alexander. His coarse nature is expressed through hard facial features and an angular chin. The hair design is similar to a dome. The soft form of processing the hair, using the so-called a-penna technique (like feathers), no longer occurs here. The face of the Maximinus Thrax is also characterized by hard folds and facial features reduced to linear shapes. A suspicious look - which is common to all portraits of the emperors of this era - is also evident in this portrait and can evoke the imperial crisis of the 3rd century .

The styles that were used under Maximinus Thrax also changed with his successors Pupienus , Balbinus , Gordian III. , Philip Arabs and Philip Caesar not noticeable. This could be due to the fact that under these difficult circumstances hardly anything has changed in the personal attitude of the emperors: The serious crisis and the conflict in the dispute between imperial power and the urging of the victorious generals for rule find their counterpart in that of Worry lines furrowed the faces of the portraits. On the occasion of this unstable situation, there was a return to earlier, better times and the desire for restoration.

The persecutor of Christians, Decius , is characterized by a suffering expression on his face that is characterized by exertion and effort. The portrait of Trebonianus Gallus has calmer facial features, which is perhaps due to his origins from the Italian aristocracy . Valerian is shown as a typical soldier emperor with strict features, the characteristic short haircut and a face furrowed with wrinkles.

The reign of Gallienus is seen through his restoration policy as a turning point in that age of crisis. Gallienus differs from his predecessors not only in his portrait: one can speak of a Gaulish Renaissance or a classicism . A new spirituality is expressed through the high education of this emperor. His restoration policy is reflected in a kind of savior portrait. With its hairstyle and hairstyle, the portrait of Gallienus was at times based on Augustus and thus in part drew on older traditions of the image of the Roman ruler , in that, for example, the pincers and forks - motifs of Augustus' hairstyle - appear on it. In later times he might have wanted to remind of Alexander the great with a curly hairstyle with strands thrown up over his forehead . The portraits of Gallienus appear far more relaxed, the surface design softer and, moreover, more relaxed than the previous portraits of the soldiers of the emperor.

The subsequent emperors Claudius Gothicus and Aurelian also tie in with this form of representation : The suffering expression, which was previously authoritative, has now receded. Emperor Tacitus goes back to the republican portrait type, whereby his facial expression seems frozen and calm. A stereometrization, a gradual flattening, cubism and spherical shape of the faces gradually established itself .

The portrait of the Probus looks strikingly angular. The face is flat, the mouth, in contrast to the flat face, is rather small and pinched. The back of the head has hardly any curves. The portrait of Carinus is characterized by more rounded and softer forms than the portrait of its predecessor.

Summary of key developments in brief

Various distinctive points of development can be seen in the portraits of the Roman emperors. It was not a question of portraying the respective emperor in a realistic manner, but of interpreting him programmatically, i.e. H. to portray how he himself wanted to be seen and how it corresponded to the respective program of rulers.

There are the following developments in these so-called round sculptural representations of the emperors:

- Octavian / Augustus

The representation refers to the Doryphoros designed by Polyklet . 3 different types of portraits are decisive for the approx. 250 portraits of Augustus, which were always only copied: the Octavian type, created approx. 31 BC. Chr. (Victory of Actium ), the Prima Porta -type, emerged about 27 v. BC (establishment of the principate ), and a type that emerged later: the Forbes type, in which only the term ante quem can be dated, i.e. the point in time before which it must have arisen, namely before the time of the establishment of the Ara Pacis , i.e. before 13 to 9 BC In all three types the depiction of the emperor's grandeur and agelessness is paramount. The 70-year-old Augustus is also shown in the picture of a 30-year-old.

After the four emperors year 69 AD, after Galba , Otho and Vitellius , Vespasian finally prevailed. It is depicted very faithfully. His face, marked by age and hardship, shows what should characterize him: responsibility for the people and the burden or burden he bears for it (Latin: onus ), as well as closeness to the citizen, assertiveness.

Trajan is also depicted realistically, but no longer as “unadorned” as Vespasian; but his representation is also less idealized than Augustus . His face expresses willpower and determination. Decorative attributes are largely avoided.

His portrait breaks with the previous representation. As a "friend of the Greeks", Hadrian is anxious to integrate the former kingdoms of the East more strongly. For the first time in the history of the Roman emperors, his portrait therefore has a beard that has been the symbol of philosophers and educated people for centuries.

The Antonines take up this development and expand it: They are also shown with a beard, but with a longer one. Her hairstyle consists of elaborate curls. This development continued up to Septimius Severus.

However, Caracalla breaks with this tradition and can be portrayed differently in the sense of the soldier emperors: no longer cautious education is recognizable in his portrait, but rather the opposite: being able to command and assertiveness. His portrait is aimed specifically at the soldiers, who could easily understand the visual message of his portrait. This is important because Caracalla relied primarily on the army in his claim to power.

Macrinus refers once more to Marcus Aurelius and interrupts the expressive, assertive depiction of the soldier emperors.

In his portrait, Gallienus refers to the beginnings of Roman portraits, namely to Augustus. His hair depiction follows on from that of Augustus in that the fork and pincer motifs are included. This is also known as the Gaulish Renaissance .

With Diocletian, the realistic portrayal of ruler disappears. Contrary to a veristic - that is, realistic - mode of expression as in the Vespasian portrait, a stereotypical mode of expression is introduced here again - similar to Augustus - the portraits of this period therefore make it difficult to recognize the respective depicted and are usually difficult to distinguish from one another.

Finally, Constantine breaks completely with the representation that has prevailed since the beginning of the Principate. His portraits are often oversized, their representation is much more abstract, and the gaze is no longer focused on someone opposite.

literature

- Bernard Andreae : The Roman Art. Revised and expanded edition. Herder, Freiburg in Br. 1999, ISBN 3-451-26681-4 .

- Marianne Bergmann : Studies on the Roman portrait of the 3rd century AD Habelt, Bonn 1977 ( Antiquitas , 18), ISBN 3-7749-1277-7 .

- Marianne Bergmann: Mark Aurel. 1978.

- Richard Delbrueck : Ancient porphyry works. De Gruyter, Berlin 1932 (Studies on Late Antique Art History, Volume 6).

- J. Feifer: The Roman emperor portrait. Some problems in methodology. In: Ostraka. Rivista di Antichità. 5, (1998) 45-56.

- Bianca Maria Felletti Maj: Iconografia romana imperiale da Severo Alessandro a M. Aurelio Carino (222–285 d. C.). L'Erma di Bretschneider, Rome 1958 (Quaderni e guide di archeologia, 2).

- Klaus Fittschen , Paul Zanker : Catalog of the Roman portraits in the Capitoline Museums and the other municipal collections of the city of Rome. (= Contributions to the development of Hellenistic and imperial sculpture and architecture. 3). Volume 1 (text and table volume). 2nd, revised edition. Philipp v. Zabern, Mainz 1994, ISBN 3-8053-0596-6 .

- Helga von Heintze : The ancient portraits in Schloss Fasanerie near Fulda. Philipp v. Zabern, Mainz 1967.

- Dieter Ohly : Glyptothek Munich. Greek and Roman sculptures. A guide. Munich 2001, pp. 75-92.

- RM Schneider: Counter-images in the portrait of the Roman emperor. The new faces of Nero and Vespasian. In: M. Büchsel (Ed.): The portrait before the invention of the portrait. Colloquium, Frankfurt 1999 (2003), pp. 59-76.

- Klaus Vierneisel , Paul Zanker: The portraits of Augustus. Image of rulers and politics in imperial Rome. Exhibition catalog, Munich 1978.

- Susan Walker: Greek and Roman Portraits. Reclam, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-15-010454-8 .

- Max Wegner : Gordianus III. to Carinus. Mann, Berlin 1979 (The Roman Emperor, 3, 3), ISBN 3-7861-2000-5 .

- Paul Zanker: Augustus and the power of images. CH Beck, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-406-32067-8 .

- Paul Zanker: Principle and image of the ruler. In: Gymnasium. 1979, 86, pp. 353-368.