Gallienus

Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus (* around 218 , † 268 ), or Gallienus for short , was from 253 to 260 next to his father, Emperor Valerian , co-regent of the Roman Empire and 260 to 268 sole ruler. His reign is often seen in historical research as the climax of the so-called imperial crisis of the 3rd century .

Life

Gallienus was the son of Valerian and his wife Egnatia Mariniana . He was married to Salonina and had three sons named Valerianus , Saloninus and Marinianus .

In contrast to many soldier emperors - especially after him - Gallienus came from the nobility , the upper class of the empire. When his father was proclaimed emperor in 253, Gallienus was possibly first appointed Caesar by the Senate and then shortly thereafter by Valerianus as Augustus . From then on, father and son ruled side by side and were absolutely equal, but they hardly seem to have sought contact with one another. Valerian took care of the east and Gallienus was entrusted with the control of the northern border on the Rhine and Danube. From the year 260, when Valerian was captured by the Persian Sassanids at the Battle of Edessa , he ruled the empire alone, which during his reign went through the height of the imperial crisis of the 3rd century . Gallienus was later accused of having done too little to free his father.

His rule is marked by uprisings in his own ranks and by recurring incursions of Germanic tribes into the empire. The emperor was not unsuccessful. Already from 254 to 258 Gallienus had to prove his military skill on the Rhine and Danube by putting the Germanic peoples and the Carps in their place. He prevented the tribes from crossing the border rivers, for which he was awarded the honorary title Germanicus Maximus and 257 Dacicus Maximus several times . As a result, however, the emperor could not prevent the Franks from advancing in large numbers into Gaul and as far as the Mediterranean Sea to Tarraco (Spain), which they destroyed. In 259 he succeeded in defeating the Alemanni and Juthungen near Milan, who had already advanced across the Limes to northern Italy. During this time, however, the Suebi probably overran the Agri decumates on the Neckar. In 260 a raetical contingent defeated the Germanic tribes, who were carrying loot, again near Augsburg , and many Roman prisoners were freed (see Augsburg victory altar ). At the same time, with the Limes fall, the Dekumatland was finally lost. From then on the Danube, Iller and Rhine formed the new imperial border, even if the Roman claim to rule over the Dekumatland remained in principle. The areas on the right bank of the Rhine were gradually settled by the Alamanni in the following years, and Roman civilization largely disappeared from these territories. Eventually Gallienus had to accept that the Marcomanni established a new kingdom north of the Danube, dangerously close to the Roman border. It is even reported that he took a Marcomannic princess as a second wife in order to improve relations with the powerful tribe; but this tradition has been questioned in research.

In the year 260, which was already chaotic due to Valerian's capture, the two usurpers Ingenuus and Regalianus rose up on the Danube and forced Gallienus to put order there in Pannonia . In the meantime, he gave Postumus command of the legions on the Rhine border, but this turned out to be a mistake. Postumus immediately came into conflict with the Praetorian prefect Silvanus , who had Gallienus' heir, Caesar Saloninus , in his care in Cologne. Postumus conquered the city, with Silvanus and Saloninus, who had been elevated to Augustus, were killed. Thereupon Postumus' troops proclaimed him to be the counter-emperor, who joined the provinces of Gaul , Britain and Spain. Raetia also recognized Postumus as emperor by autumn 260 at the latest. A Gallic special empire with its own administration was created, which Gallienus initially had to accept. Postumus made a wise decision not to strive for rule over the entire empire; he limited himself to the western provinces and took care of the defense of the Teutons on the Rhine border quite successfully. At the same time, Gallienus did not remain idle: Recently, the convincing view has been taken in research that Raetia had already been retaken by Gallienus in 261 (and not only 265); a (second) campaign by the emperor against Postumus then failed a few years later, as Gallienus was badly wounded by an arrow shot.

It is possible that Gallienus had to order the loss of at least a southern section of the Limes Tripolitanus shortly after 260 , as the research at the border fort Gholaia / Bu Njem in Libya by Michael Mackensen has shown, which was evacuated according to plan.

In the east, too, there was unrest after the capture of Valerian at the end of 260, because the Sassanids advanced to Antioch without encountering any resistance . The generals Macrianus and Callistus apparently succeeded in gathering the remaining Roman troops and defeating Shapur I at Korykos. The Persians then withdrew behind the Euphrates . Macrianus then had his sons Macrianus and Quietus proclaimed emperors. Though the rebellion joined Syria, Egypt and Asia Minor , it did not last long as both Macriani moved west to challenge Gallienus directly. The latter's general Aureolus - the commander of the cavalry corps newly formed by Gallienus and usually stationed near Milan - put an end to the specter by defeating the insurgents in the Balkans .

Quietus fared no better because he, who had remained in Syria, was attacked by Odaenathus and murdered in Emesa . Odenathus, the influential city lord of Palmyra , had received from Gallienus the supreme command of the entire Roman troops in the east. From 262 to 267 he recaptured much of Mesopotamia in a series of campaigns against the Sassanids . However, Odaenathus did not succeed in taking the Persian capital, Ctesiphon . Before he was assassinated in 267, he ruled the East like an independent king, although he remained formally loyal to Rome and was awarded numerous honorary titles by Gallienus.

In 268 the last great catastrophe in Gallienus' life loomed: Another great invasion of the Goths. The emperor advanced against the Goths and was able to achieve an important victory in the battle of Nestos. When the news reached him that there was a rebellion in Milan, where Aureolus had risen against him, Gallienus left the continuation of the Gothic War to his generals and set out for Milan. However, there he fell victim to a conspiracy of his officers and was slain. Gallienus was buried in a tomb on the Via Appia , about 15 km from Rome. His successor Claudius Gothicus , who at least knew about the plot, initiated the apotheosis of his predecessor, but he could not (or did not want to) prevent a large number of his inscriptions from being rejected.

Services

In the ancient (Latin) tradition, Gallienus is rated very negatively overall. He evidently drew the senators' displeasure when he expelled them from military service. Previously, numerous senators had occupied important command posts as legionary legates, but now Gallienus seems to have relied on experienced soldiers in view of the military crisis: he mostly resorted to members of the equestrian order. So it is not surprising that the senators, who finally saw themselves disempowered, saw in Gallienus the sole responsibility for all crises and problems of his reign. He was tolerant of Christians - Gallienus immediately revoked the edicts of persecution his father had issued in 260 - and paved the way for the Diocletian - Constantinian constitution by reforming the military and administration. The aforementioned creation of a mobile reaction force, consisting of heavy cavalry and stationed in Milan, belongs in this context.

The emperor has often been accused of not acting decisively enough against Postumus, Palmyra and the external enemies, but this too could be due to the negatively biased senatorial historiography . Despite heavy attacks, he was able to defend the Danube border quite successfully, the attempt to smash the Gallic special empire could not succeed because Gallienus was wounded in battle (at least he was able to conquer Raetia), and everything else would have the means at his disposal probably overwhelmed.

Gallienus was also interested in the Greek way of life, art, religion (as the penultimate emperor - the last was Julian - he was initiated into the Mysteries of Eleusis ) and philosophy - he was in contact with Plotinus - and apparently tried to turn back consciously the forms of the 1st and 2nd centuries. The emperor stayed in Rome, the ancient capital of the empire, longer than most of his direct predecessors. His reign has therefore sometimes been referred to as the Gaulish Renaissance .

Coins

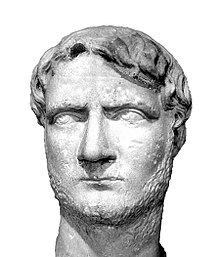

Although the coin types vary widely, looking at a large number of coins can give a good idea of the portrait head of Gallienus. Gallienus appears with full, half-length, slightly tufted hair that is combed sideways over the forehead.

His beard is cut short and goes down to his neck. Its profile appears fine and slightly broken at the bridge of the nose, with its pointed nose protruding slightly and pointing downwards. Gallienus has a slightly pointed mouth and a chamfered chin.

The bronze medallions sometimes deviate from the coin images and obviously give a more beautiful image. A crown of rays, a wreath of reeds or ears of corn, helmets or lion skin are used as headdresses.

Image types

The sole ruler type of Gallienus is characterized by the squat head shape with thick, wig-like hair. The characteristics of the velvet ruler type, however, are the raised head shape and the thin hair cap. The change from the first to the second type dates around 261.

Gallienus turned away from the portraits of the previous soldier emperors and resorted to more moderate forms of portraits that were based on late Severe or Julio-Claudian portraits. At the time of the greatest crisis, however, Gallienus completely re-styled himself and consciously shows abstract features with long hair in both of his portrait types.

He chose Augustus as a model for his portrait , with his forehead hair resembling Augustus' curls. This can be seen particularly clearly on the head in Lagos and the portraits of the Palazzo del Quirinale in Rome. In addition to the fork and pliers motif of the Augustus hairstyle, the neck hair design and the thick strands of the main hair were also adopted.

Velvet rulership type (253–260)

This head is considered a relatively youthful image of Gallienus, which comes from the time of co-rule with his father Valerian . However, additions were made to this work, namely in the area of the nose and in the middle of the upper lip. In the profile, a long rising part can be seen with a strong curve towards the back of the head. The hair is cut quite short, straight and in loose strands. A small furrow is noticeable on the forehead, which is slightly hunched over the browbones. The brow arches lower slightly towards the corners of the eyes and a small cushion can be observed over the upper lids. The slightly pronounced cheekbones lower the cheeks to the mouth and the upper lip protrudes slightly above the lower lip. In contrast to the coin portraits, the beard extends a little further up the cheeks and down the back of the chin.

Autonomous rule type (261–266)

By comparing it with coins from the time of autocracy, the head in the Museo Nazionale delle Terme can also be clearly identified as a portrait of Gallienus. Only on closer inspection can it be determined that it is the same type of portrait as in the Palazzo Braschi. The slightly rising vertex line and the furrow on the forehead are clearly visible in profile. There is also the swelling above the eyebrows, which descends outward. Likewise, the slightly pronounced cheekbones, the protruding upper lip and the sloping beard correspond to the type discussed above.

Apart from the fact that the type in the Palazzo Braschi is elongated, whereas the head in the Museo Nazionale delle Terme is rather broad, these two heads do not differ significantly. So it's safe to say that both heads are the same person. The head in the thermal bath museum is a bit older, which can already be seen from the deeply furrowed forehead. On the basis of comparisons with coins from the time of the sole rule of Gallienus, this head can therefore be addressed as the portrait of the sole ruler.

swell

As already mentioned above, the image of Gallienus is portrayed extremely negatively in the Latin sources; in the Greek, however, it is represented positively. One reason will have been the reluctance of the senators, which was reflected above all in pro-senatorial historical works such as the works that depend on Enmann's imperial history. But also deliberate manipulation by his successors, who were responsible for Gallenius' murder, could have played a role.

Several works in which the time of Gallienus was dealt with have been lost, such as the historical works of the younger Ephorus and Nicostratus of Trebizond ; the Chronicle of Dexippus has only survived in fragments.

The main source for the life of Gallienus and his warlike endeavors is his biography in the Late Antique Historia Augusta (about 150 years later) . The Historia Augusta (HA) is, however, a highly problematic source, the information of which should only be taken with great caution. Many scholars believe that the Historia Augusta's claims regarding Gallienus are for the most part fictitious. However, it is also conceivable that the late antique author of the HA had older sources that reflected the negative view of the senators (see also Thirty Tyrants in the Historia Augusta ).

In the Gallienusvita of the Historia Augusta not only his life is described, but the alleged traits of the emperor are also characterized: He was accused of indulging in circus games and other amusements instead of seeking revenge for the capture of his father. Allegedly, Gallienus even found it pleasant to be able to break away from constant observation by his father.

From the lists of the numerous negative qualities of the emperor, only a few are mentioned here: He is said to have consistently surrendered to women, wine and other debauchery and abandoned the empire to desolation, so that “every woman” could have reigned better. In addition, he allegedly showed off various luxury goods, such as purple coats and jeweled shoe straps, and drank exclusively from gold cups. In the same breath, however, he is awarded merits in the field of agriculture. He is said to have created a process that made it possible to have fresh must all year round.

literature

- Andreas Alföldi : Studies on the history of the world crisis of the 3rd century AD . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1967.

- Maria R.-Alföldi : Image and imagery of the Roman emperors. Examples and analyzes . Zabern, Mainz 1999, ISBN 3-8053-2455-3 .

- Franz Altheim : The soldier emperors . Klostermann, Frankfurt / M. 1939.

- Johann Jakob Bernoulli : The portraits of the Roman emperors and their relatives . Olms, Hildesheim 1969 (Roman Iconography; Vol. 2).

- Lukas de Blois: The policy of the Emperor Gallienus . Brill, Leiden 1976, ISBN 90-04-04508-2 (also dissertation, University of Amsterdam 1974).

- John Jefferson Bray: Gallienus. A Study in Reformist and Sexual Politics . Wakefield Press, Kenttown 1997 (unconventional study).

- Klaus Fittschen , Paul Zanker : Catalog of the Roman portraits in the Capitoline museums and the other municipal collections of the city of Rome . Zabern, Mainz 1994, ISBN 3-8053-0582-6 .

- Michael Geiger: Gallienus. Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. M. 2013, ISBN 978-3-631-64534-5 ( review by H-Soz-Kult ; review by sehepunkte ).

- Andreas Goltz, Udo Hartmann : Valerianus and Gallienus . In: The time of the soldier emperors. Crisis and transformation of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century AD. Ed. By Klaus-Peter Johne . Berlin 2008, pp. 223-295.

- Udo Hartmann : The murder of Emperor Gallienus . In: Deleto paene imperio Romano. Transformation processes of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century and their reception in modern times , ed. v. Klaus-Peter Johne, Thomas Gerhardt u. Udo Hartmann, Stuttgart 2006, pp. 81-124.

- Michael Peachin: Gallienus Caesar? In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 74, 1988, pp. 219-224.

- Arnold Hugh Martin Jones , John Robert Martindale, John Morris : P. Licinius Egnatius Gallienus 1. In: The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire (PLRE). Volume 1, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1971, ISBN 0-521-07233-6 , pp. 383-384.

- Chris Scarre: The Roman Emperors. Rulers and dynasties from Augustus to Constantine I. Weltbild-Verlag, Augsburg 1998, ISBN 3-8289-0660-5 .

- Michael Sommer : The soldier emperors . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-17477-1 .

- Max Wegner: Gordianus III. to Carinus . Mann, Berlin 1979, ISBN 3-7861-2000-5 (The Roman image of rulers; Vol. III / 3).

- Wolfgang Kuhoff : Rule and Imperial Crisis. The reign of the Roman emperors Valerianus and Gallienus (253–268 AD) . Studienverlag Brockmeyer, Bochum 1979, ISBN 3-88339-061-5

Web links

- Richard D. Weigel: Short biography (English) at De Imperatoribus Romanis (with references).

- Biography from the Historia Augusta (English) at LacusCurtius

Remarks

- ↑ Michael Mackensen : Crew accommodation and organization of a Severan legion vexillation in the Tripolitan fort Gholaia / Bu Njem (Libya) . In: Germania 86.1, 2008 (2009), pp. 271-306; here: p. 286.

- ^ Johann Jacob Bernoulli: The portraits of the Roman emperors and their relatives 2.3, 1894, coin plate V.10.

- ↑ M. Wegner, The Roman Emperor III / 3, Gordianus III. to Carinus, 1979, plate 47

- ↑ K. Fittschen / P. Zanker, Catalog of the Roman Portraits in the Capitoline Museums and the Other Municipal Collections of the City of Rome I2, 1994, Supplement 91.

- ↑ Overview of sources by Michael Geiger: Gallienus. Frankfurt a. M. 2013, p. 28ff.

- ↑ Historia Augusta, Gallienus 3, 6–9.

- ↑ Gallienus 16: 1.

- ↑ Gallienus 16: 4-6; 17.5.

- ↑ Gallienus 16.2.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Valerian |

Roman emperor 253–268 |

Claudius Gothicus |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gallienus |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gallienus, Publius Licinius Egnatius |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | roman emperor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | at 218 |

| DATE OF DEATH | 268 |