Limes Tripolitanus

| Roman dromedarius around AD 200 |

|---|

|

Link to the picture |

The Limes Tripolitanus was a border zone or military district of the Roman ruled North Africa. His chain of castles formed the easternmost part of the African Limes and served from the 2nd to the 6th century to defend the fertile coastal territories of the provinces in the area of today's Maghreb as well as from its port cities to the border of Cyrenaica . It ran from Schott el Jerid to the port city of Khoms . While the eastern borderline from the Bu Njem oasis to Telmine can be easily traced, its course east of Khoms, on the Great Syrte , is still unclear. Economic expansion in Africa continued under the rule of the Romans. However, this displaced the indigenous nomadic peoples from their traditional habitat. The border security system of the Tripolitania therefore concentrated primarily on those regions that were threatened by these nomadic tribes.

location

The Limes Tripolitanus lies on the territory of today's Libya and Tunisia . Tripolitania , "the land of the three cities", is the westernmost of the three major regions of today's Libya, with Cyrenaica in the east and Fessan in the south. In ancient times they belonged to the territories of the provinces:

|

|

According to the Antonini Itinerarium , the Limes stretched from the sedimentary basin of Lacus Tritonum ( Schott el Dscherid ) in what is now Tunisia to the port city of Leptis Magna ( Khoms ) in Libya. The chain of fortifications extended in its full length from Turris Tamalleni west of the Djebel Tebaga to its eastern end point Arae Philaenorum (Graret Gser et-Trab) on the border with Cyrenaica. The western third of Roman Tripolitania lies in the south of Tunisia, its northern border roughly along the road from the port city of Tacapae ( Gabès ) to Turris Tamalleni (Telmine) at Lacus Tritonum . Its central sector, between today's Tunisian border and the salt marshes of the Sebcha Tauorga, was the most exposed part, as it secured the gateway to the prosperous port cities on the Mediterranean. The eastern sector, with the hinterland of the three large coastal cities Sabratha , Oea ( Tripoli ) and Leptis Magna , all three former Phoenician emporia , today forms the north-western part of Libya. While the southwest border line from Gholaia to Turris Tamalleni can be traced well, its course on the Mediterranean coast, east of Leptis Magna, is unclear. This section was about 300 km long. From Auxiu (Bir el-Amari) to Arae Philaenorum , the Limes probably followed the coast of the Great Syrte, where there were only a few cities and practically no developed hinterland. Further settlement centers in the south were the oases of Nefzaoua , Ghadames and Giofra.

topography

The Limes region is unique for North Africa topographical, as it forms a semi-desert in front of the Sahara, bordered by the Atlas Mountains in the west and the Nile Valley in the east. Geographically, the former Roman border region is known in Tunisia as Djebel Dahar and in Libya as Jabal Nafusa , both sub-areas belong to a highland plateau that, as a contiguous layered mountainous country, with its southern slopes, approaches the Sahara. This mountain region stretches from Gabès to close to Leptis Magna and stretches between these points in a large arc to the south to Dehiba . The arid Djeffara depression lies between the highland plateau formed by Djebel Dahar and Jabal Nafusa and the Mediterranean Sea . South of the edge of the plateau, which is traversed by short, steeply sloping wadis, the mountainous terrain drops slightly to the south and merges into the Sahara . The eastern part is broken through by the three large wadis, Sofeggin, Zem-Zem and Bel el Chebir, which flow eastward into the salt marshes on the Great Syrte. To the west of Wadi Zem-Zem lies the stony and barren highland desert of the Hammada al-Hamra , which adjoins the sandy desert of the eastern Great Erg further west .

At the beginning of our era, the climatic conditions were very similar to those of today: dry for most of the year, but transformed into very good arable land through extensive artificial irrigation. The regions with the highest rainfall are the Mediterranean coast and the northern edge of the Djebel Dahar and the Jabal Nafusa, respectively. In the area around the Schott el Dscherid, the amount of precipitation is less than 100 mm per year. It is lowest at the location of the Tillibari fort ( Remada , TU), near the Libyan border. The mountainous highland plateau is too dry for large-scale agriculture. In the once very fertile coastal region, the Djeffara plain north of the highland plateau, there are numerous underground water reservoirs - created in the Pleistocene - and the relatively frequent water-bearing Wadi Caam (Libya). Today, however, there is much less water available there than in antiquity, which is more due to an excessive exploitation of the reservoirs and the associated lowering of the groundwater level by humans than to climatic influences.

The coastal landscape of the Great Syrte east of Leptis Magna is uniform and barren up to the border of Cyrenaica. Only a few wadis between Misurata and Sirte extend to the Mediterranean. Between the sand dunes - which stretched as far as the Mediterranean Sea - there were only a few small settlements and short river valleys ( wadi ) that only carried water during the year during the rainy season . At Berenike ( Benghazi ) the landscape is favored by more precipitation and a somewhat milder climate. This is where the Greek culture began, which shaped the east of the Roman Empire.

limes

Initially, the Latin word limes stood for paved roads leading to the enemy. The term changed and expanded over time. It ultimately referred to a border zone held by the Roman troops. The Limes in North Africa stretched over 4,000 km, making it the longest border of the Roman Empire.

The Limes Tripolitanus , a deep system of forts and military posts that secured the southern border of the Roman Empire, is mentioned in the Antonini Itinerarium (3rd century AD). According to this directory, the term referred to a route that stretched from the coastal town of Tacapae in the west to Leptis Magna to the east . At the garrison town of Bezereos , the route reached the immediate border area and then ran over the heights of the Djebel Dahar and the Nafusa mountains with the Djebel Garian via the military sites of Tentheos and Thenadassa (Ain Wif) back to the Mediterranean coast. Travelers who crossed this zone had to take two problems into account: the nature of the terrain and the ability to bring enough drinking water between the stage stations or wells. The main task of the occupying troops was therefore to control and monitor traffic in and out of Rome's sphere of influence. In this case, this did not mean securing a rigid, linear border, but monitoring the large caravan routes. The fortifications were therefore built along wadis and at oases, wells and cisterns, often the only water sources in most regions of Tripolitania. Important passage valleys were controlled by means of barriers , such as B. the one at Hadd Hajar . Potential attackers had the opportunity to circumvent forts and barriers widely, but there was always the risk of running out of water. In the 6th century, the Byzantines limited themselves to securing the coastal land on the Gulf of Gabes and the Great Syrte. The Limes consisted only of a loose chain of smaller fortified settlements and run-down port cities, which reached from Tacape (Gabes) and Gightis (southern Tunisia) via Sabratha and Oea to Lepcis Magna . These last bases of Roman power in North Africa could easily be supplied from the sea and, if necessary, evacuated.

function

The approximately 1000 km long outer border of the Tripolitania also marked an imaginary dividing line between two different cultures and economic areas and was intended to protect the economically important regions - especially for Rome's grain and olive oil supply. In a narrower sense, it was the fertile Djeffara plain on the Mediterranean coast, which in places extends up to 150 km inland. In addition, the Romanization of the indigenous population was to be promoted through the presence of the occupation troops. Their goal was primarily political - to create roughly stable, city-centered local governments with Latin as the official language. At a much lower level, it was aimed at the tribal elites outside and in the border areas in order to reconcile them with the Roman occupying power in the long term. This was accomplished through contracts, financial grants and the granting of Roman citizenship, as well as the export of goods and services. The aim was to create even closer cultural ties between the Romans and the locals. The Libyphoenicians should not be completely transformed into Romans, but only induced to identify with the advantages of Roman civilization. Under normal circumstances, the Roman conquerors did not aim to impose the Italian way of life on a completely foreign culture. Their key to success was not the violent suppression of the initial resistance to the occupation, but the gradual and voluntary assimilation of the local population into a social system based on prosperity and oligarchic power. The opposition to Rome was often overcome or at least weakened by financial and economic incentives for the subjugated elites and opportunities for advancement in the army or imperial administration. Tripolitania therefore produced numerous centurions , procurators , senators , governors , praetorians and even an emperor . In the border zone, the elite's thirst for action was deliberately directed towards the accumulation of wealth. Beyond the border, Roman diplomacy focused on installing pro-Roman rulers within the tribal hierarchies. The greatest threat to the security of the Provençals was, however, always the free nomadic people living in the interior of the country. The most important were the Nasamones, Macae, Gaetuler , Asturiani, and especially the Garamantes . The latter were semi-state organized and were ruled by a king ( rex garamantum ) who resided in the desert city of Garama .

development

Pre-Roman period until the turn of the times

Before the Roman invasion, Tripolitania was formed by coalitions of indigenous Libyans and Phoenician colonists ( Punians ) who u. a. who had built three coastal cities ruled. The cities and their environs came from 539 BC. BC under the hegemony of Carthage , which had established itself as a great power in the Mediterranean with its war and merchant navy. The Roman influence decreased from 146 BC. After the final defeat of Carthage, it increased continuously. The coastal cities were initially declared allies of Rome, but still remained independent. 105 BC After the victory of Gaius Marius over Jugurtha, western Numidia was incorporated into the Roman sphere of power, and after his victory at Thapsus in 46 BC. Julius Caesar formed the province of Africa nova (new Africa) from the kingdom of the Numidian king Jubas I , a follower of Pompey . Large parts of Numidia (Algeria) and Tripolitania also belonged to their territory. The new province was called Africa vetus (old Africa) or Africa propria (real Africa). In the same year, the coastal strip on the Kleine Syrte was annexed to the new province. During the Roman Civil War, Leptis Magna had supported the Pompeians and was therefore forced to pay Rome an annual tribute of three million pounds of olive oil. The first major military punitive action against the nomand tribes was carried out by Cornelius Balbus , 20 BC. BC, led from Sabratha against the Garamanten in Phazania , where he also stormed their metropolis, Garama . For this victory he was awarded in 19 BC. A triumphal procession granted in Rome . Between 3 and 6 BC The Gaetulians rose up in the 3rd century BC, and were also joined by the Nasamons and Garamanten. Thereupon Augustus appointed a general to quell the revolt, which was unusual for a province under the control of the Senate. Under Augustus Tripolitania officially became part of the Roman Empire. Today's Tunisia and the coast of Tripolitania were from then on part of the Africa proconsularis province .

1st century

The origins of the Limes are still largely in the dark, because archaeologically and epigraphically, the first two centuries AD are not very informative in this regard. Written sources do not provide clear information about the early development of a coherent defense system. The first fortifications were probably built under the rule of Augustus (31 BC to 14 AD). The priority of Rome during this period is likely to have been to control the indigenous tribes rather than to establish fixed borders. The soldiers were fully occupied with the territorial reclamation (land surveying and building roads). The occupation of Tripolitania did not initially have any major impact on the interaction between city dwellers and the desert nomads. Now and then forays into the interior were made. This was only intended to remind the desert tribes of the Roman presence. They also wanted to find out where they were in the spring. Their activities were initially only a minor threat to the African provinces, as their survival also depended on peaceful coexistence with the settled farmers and townspeople.

Because of the economic development promoted by the Romans, conflicts were soon inevitable, as they more and more restricted the traditional way of life of the free peoples. As a result, the Gaetul , Nasamones, and Garamanten tribes were soon hostile to the Romans . By 6 AD, some groups of them could be subdued. Only a few troops remained in Tripolitania to hold them down. One of the most important battles for supremacy in Tripolitania most likely took place in 18 BC. Instead of. Lucius Cornelius Balbus Minor defeated the Garamanten and Phazanii. His victories also included the conquest of Cidamus , the capital of the Phazanii. The situation escalated completely during the reign of Tiberius , when tribal warriors, mainly Musulamians and Garamanten, led a guerrilla war against the Roman occupiers under the leadership of Tacfarina and often struck in several places at the same time. You were the generals Cornelius Scipio opposed and P. Cornelius Dolabella, the latter founded in the year 24, after several victories over the insurgents in Leptis Magna the Victoria an altar. In the course of this, the consul Quintus Junius Blaesus established the first permanent military bases in Tripolitania in order to limit the rebels' radius of action and to better secure the approach roads. New land was constantly being developed. Even that which is far from the coastal cities and previously only used as pasture for cattle has been converted into arable land. Because of the new, well-developed roads, the products from these regions could now also be sold profitably on the marketplaces of the cities.

The general Septimius Flaccus led another major military expedition in 50 AD, in which he led his troops deep into the Fessan . The last great raid of the Garamanten to the Mediterranean coast took place in 69. The trigger was a bitter border dispute between the cities of Leptis Magna and Oea , which even prompted the latter to ask the hated Garamanten for support. Leptis Magna could only be saved from destruction through the intervention of Roman troops. Valerius Festus then carried out a punitive expedition against the Garamanten in the year 70, stormed their capital and forced a new peace treaty on them. The first Roman fortress was built in Thiges around 75, during the reign of Emperor Vespasian (69-79), to protect the settlers on Schott el Dscherid from attacks by the Gaetulians.

2nd century

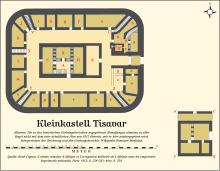

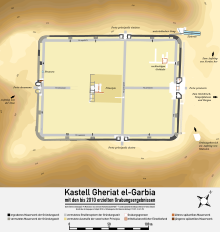

In the early 2nd century, the area around the Nefzaoua oases and the northern Dahar were largely pacified. In the Cherb region, the first barriers could therefore be built. Under Hadrian (117-138), who also visited Africa on his great tour of the empire in 123, the nomadic tribes were expelled from the area south of today's Gabès . At the same time, the construction of new fortifications was pushed. Then the Tillibari fort was founded on a busy caravan route from Ghadames to the Kleine Syrte . The Tripolitana itself remained largely without significant military protection, as it was not yet very well developed economically. It was not until the reign of Commodus (180-192) that there were permanent garrisons in Bezereos and in Tisavar , which was laid out deep in the eastern Great Erg , on the border with the tribal areas, both at the western and at the Tunisian end of the future Limes. The Thenadassa fort in Djebel Garian - despite its building inscription from the 3rd century - was probably founded as early as the 2nd century - initially as a small fort . For Zintan and Mizda , both in the Upper Wadi Sofeggin, forts from this period can be assumed. Places such as B. Praesidium (Si Aioun) also suggest military bases founded before the 3rd century. In the regions around the Sofeggin and Zem-Zem wadis, olive oil production increased enormously at this time, as demonstrated by 60 oil presses there. They were mainly operated by Romanized farmers and testify to the strong cultural and economically sustainable change in these areas. On the road from Mizda to Fessan , numerous road watch posts were built in the 2nd century. North of Mizda lies the Clausura of Hadd Hajar and the small military station Medina Ragda , which, judging by the ceramic finds, also arose in the 1st or 2nd century. Further outposts were established with the Centenarium Gasr Duib and Gasr Wames also in the Upper Wadi Sofeggin. The army bases in Gheriat esh-Shergia , Gheriat el-Gharbia and Tentheos are all likely to date from pre-Severian times. The Limes was expanded under Hadrian. The small fortifications Bezereos and Tisavar, founded in the late 2nd century, intensified control over the areas occupied since Hadrianic times. However, this only closed gaps in the Limes zone, but did not draw completely new borders. At this time, older watchtowers were repaired and new ones built.

3rd century

Under Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211), the province of Africa proconsularis was divided into Africa and Numidia in 198 AD . The Limes was expanded still further, at the height of Cidamus ( Ghadames ) the security line was advanced to the east to the edge of the Sahara and north of the Hamadah al Hamra stone desert. The governor Quintus Anicius Faustus was in charge in the years 197–201. His army reached the Garama metropolis . Faustus increased the number of road posts and thus expanded the control zone by up to 400 kilometers to the south. Furthermore, veterans were settled in order to make the dry land arable through artificial irrigation. In order to be able to defend the cities of Tripolitania even better, the army also occupied some Fezzan oases. This campaign started from Tillibari Castle. According to Edward Bovill, camels were used as pack animals for the first time. The Garamanten were again forced to sign a peace treaty and became a client state of the Roman Empire. The attempts at romanization did not have a major impact on them, however, as they a. could not be convinced of the advantages of trade in goods. In the same period Gheriat el-Garbia was expanded to become the largest of the Tripolitan border fort . In addition to the small fort Bezereos, which was also important and was built by a vexillation of Legio III Augusta , the fort Cidamus , which was advanced far beyond the actual border, was also documented in the years between 209 and 211 AD. The rear fort Thenadassa, postulated in particular by David Mattingly , and the Auru (Ain el-Auenia) confirmed by a building inscription dated between AD 197/198 and AD 211 could belong to the other new constructions of this time . Another new establishment of this period was the small fort Gasr Zerzi. There, two building inscriptions confirm its construction around 209 AD. With the expansion of these fortifications along the newly created border line, the Roman expansion in Tripolitania came to an end.

According to a building inscription from Gasr Duib, the Limes had been divided into several sectors (e.g. Limes Tentheitanus ) since the time of Emperor Philip Arabs (244–249 ). These border protection sections existed well into late antiquity, as evidenced by an inscription mentioning the Limes Tentheitanus , which was created during the second half of the 4th century or even in the first half of the 5th century and was discovered in the Gheriat el-Garbia fort. There, too, the Limes Tentheitanus is still called. Nevertheless, advances by nomad tribes from the Sahara threatened the coastal towns in Tripolitania again and again. In 238 Gordian I was proclaimed emperor by the great landowners of Africa, his son and co-regent, Gordian II , was shortly afterwards defeated by the Numidian governor Capelianus with the help of Legio III Augusta and by Moorish equestrian associations. His grandson, Gordian III. , had the Legion disbanded 239, which soon became a major security problem for the African provinces. In 253/254, Emperor Valerian reorganized the legion to strengthen his army in the war against the Quinquagentiani (Five Tribes) and the Fraxinenses , a federation of Berber tribes that were now increasingly threatening Roman territory. After 260/275, the southernmost outposts in the region between Gholaia and Gheriat el-Garbia were abandoned. Severe defeats on other border sections of the Roman Empire, including the fall of the Upper Germanic Limes , constant civil wars between rapidly changing usurpers , a lack of trained soldiers and strategic considerations may have prompted Emperor Gallienus (260–268) to make this decision at the height of the imperial crisis. The border line was moved back at least in the area around the Gholaia fort. According to David Mattingly, however, the entire borderline in Tripolitania was not shortened. The building inscription of the Talalati fort reports on the construction of this fortress in “a favorable place” under Emperor Gallienus (260 to 268). The perseverance of the soldiers of the Limes Tripolitanus is also praised. So z. B. also the fort of Mizda around 275 to have been occupied. The final coin from the small fort Tisavar, minted during the reign of Emperor Maximinus Daia (305-313), also indicates this. The detachments that had previously been distributed among the forts, small forts and oases were now concentrated in the larger forts.

4th to 5th century

The first evidence of an independent province of Tripolitania goes back to the time of the imperial reform of Diocletian (284-305). At that time (294–305) the Byzacena, Tripolitana and Zeugitana emerged from the province of Africa proculensis . At that time there were only a few regular troops in the province and the bases of the mobile field army ( Comitatenses ) were usually too far away in case of danger. Tripolitania was again ruled by the local magnates , whose authority was based on the traditional tribal order, their status as landowners and the tacit tolerance of the Roman administration. In the last third of the century the Asturiani invaded Tripolitania , according to the chronicler Ammianus Marcellinus "... more violently than usual ...". Synesius of Cyrene wrote that the raids of the looters in Cyrenaica had been provoked by the Romans, since they had withdrawn a large part of their troops and the rest were poorly equipped: "... what enemy would not enjoy a war, who was so little dangerous ... “and complained about the ineffectiveness of the Roman defense. The peasant militias on the border were faced with a dilemma. The decline in the monetary economy, in particular, had reduced their motivation to continue defending the province - without any support from regular army units. In order for the settled farmers and shepherds to survive in the long term, they had to come to terms with the desert tribes in some way or another. So it was again the coastal cities that suffered more attacks. It is believed that the population in the border zone was either assimilated by the tribes or often made common cause with them. Be that as it may, she apparently got along better with the new power-political realities. Rome (and later the Vandals and Byzantines as well) continued to conclude peace treaties with the free tribes, but - in contrast to the earlier hegemonic alliances - these were only fragile non-aggression pacts. The resurgence of tribalism was initially most pronounced in eastern Tripolitania, but in the early fifth century it spread to the west and even to the coastal countries. Despite these unfortunate circumstances, the border guards continued to exist at all times. In the far south, on the edge of the rocky desert Hammada al-Hamra , Gheriat el-Garbia fort, which was abandoned in the course of the verifiable withdrawal of the border line between Gheriat el-Garbia and Gholaia around AD 275, took place around 360/380 , perhaps not until the last quarter of the 4th century, a renewed use and extensive repair took place. In addition to other reconstruction measures and reinforcements on the surrounding wall, which, according to radiocarbon measurements, date to 420, a high-quality reconstruction of the Severan Principia can be observed, in which large parts, such as a newly built colonnade, were created. The renovation work on the staff building can be located radiocarbon dating from around 390 to 425. The effort made proves that long-term use of this location was planned. The Roman military ( Limitanei ) , which was probably again stationed here, was supposed to regain control of the near-desert area of the province of Tripolitania as a protective power and to take action against predatory attacks. As the ostraca recovered in Gheriat el-Garbia show, a North African unit was apparently stationed there that spoke a southern form of Punic .

In 429 vandals and Alans overran the Dioecesis Africae . As the range of ceramics from the small fort Bezereos shows, the Tripolitan Limes seems to have been abandoned by the border guards sometime between 430 and 440 AD. In 455 at the latest, when the province of Tripolitana fell into the hands of the vandals, the end probably came for Gheriat el-Garbia as well. Many Limes forts survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire, albeit with some difficulties, as the big cities fell into more and more decay. The invasion of the vandals did not bring about any profound changes for the life of the Provençals. The conquerors claimed some of the most fertile areas for themselves, but without driving the Coloni from there. In other areas, the Romano-Africans worked their land as before, and the Vandals made treaties with the free tribes outside their territory for their protection.

6th to 7th centuries

In 534, after the subjugation of the Vandals to Eastern Roman rule, Emperor Justinian placed North Africa under a Praetorian prefect . At the same time, a Dux limitis Tripolitanae provinciae based in Leptimagnensi was used again. Most of the centenaria were also still inhabited; some of them were even converted into fortified palace villas ( Castra ), such as B. in Suq al Awty. The late antique historian Prokopios of Caesarea reported in the 6th century AD. a. that the inhabitants of the city of Ghadames were allies of Rome from ancient times and renewed their treaties with Justinian. However, the recapture was not very popular with the rural population, as the new rulers proved to be more efficient tax collectors than the Vandals. The Tripolitana was still considered a prosperous province until the Islamic expansion. Olive oil production increased again and the Provençals were able to generate a modest prosperity. In the time of Byzantine rule, however, there was a further decline in Latinity , Romanization and urban life. Justinian nevertheless had the coastal cities, which had been badly affected by the looting of the Moors and Asturiani, fortified again. Sabratha and Leptis Magna were fenced with new, very massive walls, the remains of which can still be seen. In Gightis a small fort was built on a hill above the town. Likewise, the cities of Cyrenaica were again manned with garrisons and fortified again, these walls (6th century) are also partially visible. After defeating the Vandals, Cyrenaica flourished again for a short time. The port city of Apollonia became the new metropolis . With the elevation to the provincial capital, the city was equipped with important public buildings, including some basilicas and the palace of the Dux of the occupation troops, who presumably resided there. Sometimes the army came into conflict with the Berber tribes and new borders were established. Byzantine Tripolitania, however, never extended very far beyond the coastal plain and peace depended on the benevolence of the desert tribes. The Byzantines were able to hold their own in North Africa until the middle of the 7th century.

By 643, Arab invaders had occupied Cyrenaica and the eastern half of Tripolitania. They became the starting point for the conquest of the Maghreb . From 647 onwards, as part of the Islamic expansion, they advanced further into North Africa. The imperial exarch Gregory , cut off from supplies from Constantinople, succumbed to the overwhelming power of the Arabs after a brief resistance, who soon afterwards founded the new province of Ifrīqiya with the capital Kairouan . This ended late antiquity in Africa . In the 11th century, nomad warriors of the Banu Hillal destroyed the last remaining Centenaria and Castra , which largely brought agricultural production to a standstill. Leptis Magna and Sabratha were finally abandoned. Only Oea was still inhabited and developed into today's Libyan capital Tripoli .

troops

A numerically small army was sufficient to protect North Africa. The 17 auxiliary units, which were located in North Africa in the 2nd century, also had five aalae and six mounted cohorts in their ranks, which were indispensable for controlling the extensive terrain. After the clashes in the civil war (49-46 AD) and the victory of the Romans in the Tacfarinas uprising (14-37 AD), it remained largely quiet there for a long time. The governorship of Africa was considered to be the most prestigious next to that of Asia , especially since the proconsul of Africa was the only senatorial governor to command an entire Roman legion for a long time , an office that was otherwise reserved only for the imperial legates . The African army ( exercitus Africanus ) had been distributed to many locations in the interior of the country so that insurgents would not be able to retreat. Tacitus et al. Reports on the revolt of Tacfarinas . a. that he had to withdraw again and again deep into the desert to raise new troops. Under Septimius Severus (193-211), the army in North Africa had a legion, two alae, seven cohorts and two number units. During this time, a decentralization of the chain of command was initiated in North Africa. The local commanders were thus given greater freedom of choice, presumably because of the great distances between the individual military posts. After the dissolution of the Legio III Augusta between 238/239, the defense of Tripolitania had to be maintained exclusively with auxiliary units. The number of teams in some associations was then increased to 1,000. Presumably the legionaries were demoted and assigned to the auxiliary forces. These were now subject to a Praepositus limites Tripolitanae , which probably replaced the legionary legate and was subordinate to the governor of the province of Numidia . From the 3rd century onwards, the African army increasingly consisted of indigenous Berbers and Libyans. Soldiers who could easily communicate in their mother tongue were certainly an advantage in the field, but they diminished the usefulness of the army as a carrier and disseminator of Romanization. The border protection was reorganized under Emperor Philip Arabs (244–249). It is believed that then the border troops were concentrated in the most endangered border sections. The Limes was subdivided (perhaps as early as 238 to 244 under Gordian III. ) Into sectors, and a Praepositus limitis (a vir egregius in the hierarchy of the Roman nobility ) and its subordinates ( tribunes ) were responsible for securing them. One of these Praepositi , Lucretius Marcellus, is known from an inscription found in Gholaia. The staff units of the Limites were in the rear cohort forts. They were also named after these, such as B. the Limes Tentheitanus or the Limes Tillibarensis . This classification was retained even after the Legion was rehabilitated and reestablished, 256. Despite all these measures, the attacks by the nomad tribes could never be completely stopped.

legion

The core force of the provincial armed forces was the Legio III Augusta , which first lay in the camp of Theveste and was transferred to Lambaesis under Trajan . Many of their vexillations were assigned to guard duty in the border fort for a long time. The small fort Tisavar was z. B. manned by legionnaires until the middle of the 3rd century. The camp commanders of the Gholaia Fort, all with the rank of centurions , had always been detached from the Lambaesis legionary camp between 201 and 238 AD . Legion divisions were also located in the forts of Cidamus, Gheriat el-Gharbia and Gheriat esh-Shergia.

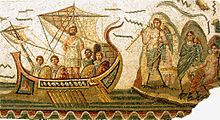

Auxilia

In addition there were the Alae and Cohors of the auxiliary troops ( Auxilia ). Associations of the numeri collati are also known. Apparently they were only used in the African army. Units of selected soldiers who were entrusted with different tasks under changing commanders were designated as such. After completing their special mission, the soldiers returned to their regular units. Preferably in the eastern provinces, the Romans also set up camel rider units ( dromedarii ), which were mostly assigned to the Cohors equitata . Both the dromedary ( Camelus dromedarius ) and the Bactrian camel ( Camelus bactrianus or Camelus ferus ) were well known in the Roman world. They were bred for military as well as civilian freight transport. Especially in the late Roman period, the state maintained a large number of camel colonies who provided the army with the necessary supplies on their campaigns. In addition, they were also used for field work in the southern provinces. Contemporary written sources mention the consumption of camel meat and their milk. The animals were apparently also used as pack animals in the northern provinces, as shown by bone finds in Britain and Gaul.

Fleets

The control and surveillance of the Mediterranean coast ( Mare Libycum ) was the responsibility of the Classis Alexandrina (since 30 BC) and at the end of the 2nd century also the Classis nova Libyca ( Ptolemais headquarters near Toqra ). The provincial governors also commanded the fleet soldiers.

Late antique military organization

After the military and administrative reforms in the 3rd century, the border troops were divided into mobile ( Comitatenses ) and stationary units ( Limitanei ), which were commanded by Comes rei militaris and Dux limites . Even after 300, with the founding of the Province of Tripolitania , the military administration should not have changed significantly. The list of troops of the commander of the African field army ( Comes Africae ) was handed down in the Notitia Dignitatum Occidentum (western part). He had a total of 12 infantry, 19 cavalry units of the Comitatenses and 16 units of the Limitanei , which were recruited from the local population. Often whole tribes were recruited as border guards ( foederati ). The Arzuges tribe is known in this connection from the letters of Augustine of Hippo . One part was Christianized, the other still adhered to the old belief in gods. A total of 31 regiments are listed in the Notitia for Africa, which probably comprised between 15,000 and 22,000 men. The 28 infantry units were distributed among garrisons from Tripolitania to Mauritania and probably numbered around 10,000 men. The equestrian associations were among the Palatini or Comitatenses , who were under the command of the two western magistri militum . Only the Legio tertia Augusta appears as the main unit . The high number of riders is likely to be due to the constant threat to the borders from nomadic tribes. The information in the Notitia Dignitatum presumably represents a snapshot of the troop strength around the year 420. Whether some of the Limitaneiverbände are identical to the Comitanses under the command of the Comes cannot be answered, since the Notitia only contains information about their stationing locations. During this time the regular military was reduced to the bare minimum and mainly concentrated in the western part of Africa. Rome's decision to in fact leave the defense of the African provinces only to the small field army of the Comes Africae made the old Limes obsolete.

The Tripolitan land troops - and perhaps also naval units - were under the command of a Dux provinciae Tripolitanae , who was probably deployed before 400 AD and resided in Lepcis Magna . For some time the leadership of the provincial military and civil administration was exercised by the same incumbent. At the beginning of the 5th century, a Comes et Dux commanded the Tripolitan army , probably due to the increased risk . According to the Notitia Dignitatum , the provincial contingent consisted entirely of limit units. It is noteworthy that they are not given by name, only the 12 Limes sections. At that time each of them was evidently under the command of its own Praepositi limitis . It appears that their associations consisted mainly of militiamen who earned their living as farmers and only took up arms when the desert tribes invaded. In addition to their military duties, they probably also had police duties and monitored a. a. the activities of farm laborers. Over time, these gentiles produced their own culture, the traces of which can be traced back to the time of the Islamic conquest.

Military infrastructure

Tripolitania was the starting point for caravan routes to the south of Africa. These had to be kept free by the Roman army. The Limes facilities therefore formed a deeply tiered defense system and mainly comprised small forts, barriers, individual watch and observation towers, but also customs stations that controlled and channeled trade and travel. At focal points there were cohort forts between which even smaller guard posts were placed, by means of which communication between the individual bases could be maintained. The rest of the inland was monitored from the small forts, road stations, clausurae and ksars. In addition, villages and farms were fortified, whose residents were supposed to ward off minor nomad attacks. Barriers with walls and ditches were built at pass crossings and in valleys, which could also be monitored from towers. The border defense relied on around 2000 such fortifications. The Numidian forts were not located directly in the surveillance zone to the Sahara but in the more water-rich areas south of the Nementcha and Tebessa mountains. Those forts in which the larger contingents of the regular troops were stationed were on the edge of the semi-desert.

Castles

The camps ( Castra / Castron ), which were mostly built in the 2nd century , basically did not differ significantly from those existing in the western provinces. Their floor plan was rectangular and they had the same standard internal structures as in the center the headquarters (principia) , the commandant's house (praetorium) , one or two granaries (horrea) and team barracks (contubernia) , possibly also functional buildings such as a bathhouse (balineum) , Workshops (fabricae) , bakeries and a latrine. These camps could accommodate 500 to 800 men. Since many camp villages ( vici ) in North Africa were walled around and the forts were mostly located within or on the outer edge of the civilian settlements, these also protected the forts. The forts did not have a ramp filling behind the wall due to a lack of suitable material. Permanent occupation was not possible without a secure water supply. In the vicinity of the small fort Bezereos a dam was built, which in the rainy season led the water dammed there into basins and cisterns. These could hold up to 60,000 liters of water. The Gholaia camp bath had two cold bathing rooms, a warm water basin, a latrine and the so-called Fortuna Hall. Although there was a spring inside the fort, the 50,000 liters of fresh water required for bathing must have been collected in cisterns and fed into the bathing building via a pipe system. As with other Limes forts, the African camps also went through several renovation phases. For example at the castles Tillibari and Gheriat el-Garbia.

Small fort

Also called Ksar , they served as road patrols and usually measured 0.5 to 0.12 hectares. In the courtyard-like complex there was a central building that housed the camp commandant. The two-storey crew quarters of such bases were arranged along the wall, the roofs of which served as battlements. Between 50 and 100 men were stationed in such small forts. The best known, the small fort Tisavar, had rounded corners and only one gate. Inside there was also a small shrine to Jupiter. Two smaller road stations could be identified at Medina Ragda and Auru . Both locations had bathhouses and later turned into civilian settlements. The excavations at Thenadassa Fort , originally identified as a road station, have supported this interpretation. The station was named after a nearby spring and stood on a hill on the northern edge of the Djebel Garian, a section of the Nafusa mountain range, about 75 km south of the coast. An inscription indicates the presence of a cohort of Legio III Augusta . Under Philip Arabs new small forts were built.

Centenaries

The smallest fortifications on the African Limes were the centenaries or burgi. The square buildings, first built in the 3rd century, covered an area of 0.01 to 0.10 ha on average and were in strategically favorable positions. Their mostly windowless outer walls were built very massive, the only entrance was particularly well protected. Light and smoke signals could be transmitted from the roof to the neighboring guards. Judging by the building inscriptions found there, they were often built under the command of a centurion. However, their name cannot be derived from this military rank or department ( centuria ). Most of the centenaries did not emerge until the 4th century. The Tibubuci and Gasr Duib centenaries are the best known of these fortifications. The term is already handed down in a - clearly military - building inscription from the Gasr Duib Centenarium built in Wadi Soffegin, which was founded during the reign of Emperor Philip Arabs (244–246). Thus, two small forts on the Limes Tripolitanus and Limes Tentheitanus are known to this day, which bore this name. The discovery of these inscriptions sparked a discussion among experts regarding the exact meaning of this term. If it was previously believed that these fortifications , known as Qsur , Qasr , Gasr, Ksur or Ksar since the Arab conquest of North Africa , were exclusively military structures, the archaeologist Erwin Ruprechtsberger took the view that the majority of them were fortified farms - so-called fortified farms - served in the run-up to the Limes. From this time on, they would have been built by former soldiers or by military or paramilitary organized provinces who were supposed to maintain the border defense. This theory can be traced back to Jérôme Carcopino (1881–1970) and Richard George Goodchild (1918–1968). David Mattingly referred to more recent research and said that these considerations were out of date. In contrast, he expressed the assumption that the Ksur (plural of Ksar) in the chain of castles in the Limes and at other neuralgic points in the hinterland would continue to be addressed as a troop camp.

Watchtowers

Watchtowers ( burgi speculae ) secured the roads between the forts and the coast and the barriers. From there, the crew ( speculatores ) had a line of sight to the nearest fort or settlement, which can still be seen particularly well today at the forts Talalati and Gheriat al Gharbia. According to the building inscription, the circular burgus built during the reign of Emperor Severus Alexander (222–235) has a diameter of around five meters and has been preserved for around six meters. One of the towers (Tower II) of the Tebaga-Clausura had a round floor plan with a diameter of eight meters. In addition, it was surrounded by a wall and ditch (diameter 25 meters). Apart from their residential function, the Tripolitan Towers can be compared to those on the Trajan Column. In addition to round towers, there were also those with a rectangular floor plan, such as the three watchtowers of the Hadd-Hajar-Clausura.

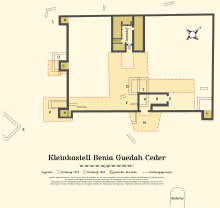

Barriers

Straight across the mountain valleys, which are important for through traffic from or into the Sahara, linear systems of quarry stone / mud brick walls or rubble dams ( clausuare , fossata or propugnacula ) were built, which in some cases were reinforced with watchtowers and tower-reinforced gates ( Wadi Skiffa , Hadd -Hajar). The barrages on Djebel Demmer were directly connected to the small fort Benia bel Recheb to the north . With them the trade and the annual migration of the nomads with their animal herds to the Mediterranean coast should be controlled and controlled. Presumably they were held back there until the grain was brought in, only then could they lead their herds to the harvested stubble fields for grazing and fertilization. The first barriers in Tripolitania were probably not built until the 3rd or 4th century.

Civil defense systems

Walled farms and similar fortified sites shaped the landscapes of late ancient North Africa. They were called Qsur, Qasr, Gasr, Ksur or Ksar by the Arabs who did not invade until the 7th century and who no longer understood the different meanings of the different architecturally similar civil and military structures. The increasing uncertainty at the beginning of the third century was one of the reasons for the introduction of a more defensive architectural style. The crops from the surrounding farms were stored in the Qasr and served as a refuge in the event of danger. In some cases they probably also served as regional administrative centers. The oldest constructions of this type can be dated to the 2nd century AD. In Libya they reached their technical climax in the 4th century. They could be used in all North African provinces, including the tribal areas outside the borders, such as B. the Fessan Garamanten be observed. There are, however, considerable regional differences, e.g. B. fortified villages in Numidia, walled temples and mausoles , permanent houses in the Tunisian dry steppe and fortified churches in Cyrenaica. In almost all areas they were the central elements in the settlement hierarchy, in Tripolitania and the Fessan even the dominant architecture. Some were modeled after the Roman castles. Their development continued into the Islamic period. They emerged as a reaction to the growing threat from predatory nomads and cost reductions in the military by withdrawing soldiers and increasingly leaving border security to the military farmers.

A qasr had a tower-like structure, usually about 18 x 18 m, with wide outer walls, an inner courtyard (or light shaft), and a single entrance. A total of six building types are known, which differ mainly in their floor plans.

- Type I: all living rooms faced the inner courtyard, which took up the entire opposite wall,

- Type II: it had an inner courtyard, the living rooms were arranged on two or more sides of the building, sometimes with an arcade on the entrance side or a tower-like entrance,

- Type III: it consisted of very wide outer walls and interiors without a door, which suggests that access was only possible from the second floor or the roof,

- Type IV: had a large garden in the center, the living rooms were arranged around several inner courtyards,

- Type V: Buildings with an irregular floor plan, as they stood on rock spurs or hills and finally

- Type VI: those Qasr that could not be assigned to any of the above building types.

Streets

The chains of forts and posts essentially ran along roads that opened up the Mediterranean coast, the immediate border area and the highlands. Since there were no natural transport routes such as rivers in the interior of the country, good road connections were essential for logistics and communications for the Roman troops in North Africa. Most of them were unpaved slopes. Its installation began as early as the 1st century when the Legio III Augusta moved into its first camp in Africa and the connection to the supply ports on the Mediterranean had to be secured. With the advancement of the border zone, the road network was also constantly expanded. Under Tiberius , on behalf of the proconsul L. Aelius Lamia (15-16 AD) from Leptis Magna , a 44 Roman mile long road was laid in a south-westerly direction that led to the Tarhuna plateau . Although it was primarily created for the army, there is no evidence that it was mainly used for military purposes in the first few years. In the Antonine Itinerary is Iter (Route) III as an inland road to Limes Tripolitanus specified. It branched off from routes I and II, which ran along the coast to Leptis Magna . The military camps were mainly lined up on a road to the east that began at Tacapae and reached Leptis Magna on the Mediterranean coast. Here was the main line of defense, which consisted of at least 18 fortifications, forts and watchtowers. A second road began at Tentheos, near the sources of the Sofeggin and Zem-Zem wadis, which opened up the Garian plateau. The road to the south-east was secured by the auxiliary troop fort Bezereos, which was built under Commodus . From Tillibari there were road connections to the Tripolitan Djebel and south to the Ghadames oasis. In the region around the Hadd-Hajar-Clausura there were two routes through this part of the highland plateau, the main road could be controlled by the Clausurae, while the other passed either through settlements or by Qsurs, who dominated the valley. In Cyrenaica, due to the lack of more densely populated areas, no major road network developed. With the exception of the Barka Mountains, the roads were concentrated on the coast. The small-scale road network in the Barka region is not taken into account in the itinerary . The remaining Roman roads are listed as routes II.3 and II.Aj.

Kastellvici

In the camp villages ( vicus ) were the living quarters of the relatives of the soldiers, veterans, craftsmen, traders, innkeepers, prostitutes and other service providers. Often they were granted self-government soon after they were founded. The vicus of Fort Gholaia was typical of such civilian settlements . Allied tribal princes also resided there - temporarily. The vicus covered an area of 15 hectares and was created at the same time as the military camp. The settlement of Talalati Fort, on the other hand, was probably built before the fort was founded. Many of the Vici were given up again after the fort crews left. Gholaia was surrounded by a multi-phase wall which, however, would not have withstood longer sieges. The 10 hectare vicus of Tillibari was also surrounded by a wall. Where wadis offered sufficient protection, no walls were built. The interior development of Gholaia was irregular, the plots were apparently not - as with Vici on the northern border of the empire - first measured and then assigned for development. Because of the drifting sand, the Roman ruins were often preserved up to the roof approach. For the vaults, palm trunks formed into arches and mortared were used as supports. This type of construction has survived into our century. Graffiti on the walls suggests that they were mostly inhabited by Libyphoenician traders. In addition to a necropolis, five temples were discovered. In addition to the Roman god Iupiter, the soldiers in Bu Njem also worshiped the Libyan deities Cannaphar and Ammon . The vicus was inhabited until the early 5th century. The simple farm workers probably lived in small, oven-like vaulted straw huts (Latin: mapalia ) that the nomads carried with them and from which they formed their camp.

population

In addition to the indigenous Libyphoenicians, the population consisted of soldiers and immigrants from all parts of the empire. Other settlers were nomads who had become settled. From 220 onwards, many immigrants from the Middle East and Syria also come to Tripolitania . In this way, over time, it became an ethnic melting pot. A name like that of the provincial Julius Mashalul ben Chyrdidry contained Latin, Semitic and Libyan elements, they were not unusual for this province. Their slow cultural transformation through political, social and economic influences at the time is also archaeologically tangible. Retired legionaries often received parcels of land along the wadis, in the dry steppes between the oases and in the surrounding area of the three coastal cities as compensation. Since the country was never completely dominated by the Roman colonists, the pre-Roman social structures survived. Most of the long-established provincial residents were only superficially Romanized. Punic and Libyan elements continued to predominate in their language, culture and religion. In many parts of the Limes hinterland obviously a patronage system has passed in which the - important for the supply of troops - Coloni were involved. The peace and political stability guaranteed by the Roman military over time created a rural upper class whose culture and production of goods were not only based on the Roman model, but also on the already existing Libyphoenician aristocracy of the emporia . The Roman supremacy only existed as long as it was supported by this landed gentry. At the turn of the ages from the fourth to the fifth century, it increasingly waned. Even before the Arab invasion, the population of Tripolitania had largely regressed into a rural tribal society. After the establishment of Arab rule, Christianity proved to be the most resilient part of Roman culture and was able to persist well into the Middle Ages.

economy

The agricultural products of the African provinces were brought into the trade chains of the Mediterranean area under the Romans, thereby establishing Tripolitania as one of the most important food suppliers in Rome. For millennia, the oasis economy in North Africa with the date palm as the key plant was at the center of economic life, which was essentially geared towards the self-sufficiency of the population. The only export items were the dried date fruits, which could be kept well in this climate, which could be transported by camel caravans to the markets in the south (Black Africa) and north (Mediterranean coast). This also brought a variety of exotic goods and precious metals (gold) - some of which were traded as luxury goods in Rome - to the coast and later to the European part of the Roman Empire. Also an important staple food and preservative, the rock salt obtained in the Sahara and Sahel , from which the historian Herodotus in the 5th century BC. Reported, was negotiated to the coast. The exchange of goods and services between sedentary people and nomads was also important. The former cultivated food in areas with sufficient rainfall, while their nomadic neighbors roamed the arid zones with their herds of cattle in the constant search for enough pasture land . B. the Gebel as-Soda and the outskirts of the Sahara . From winter to spring they moved from oasis to oasis, at the end of summer they drove their herds either to the area of the Schott el Jerid (Tunisia) or to the coast of the Great Syrte . The farmers built terraces in the wadis and built dams and canals made of stone and clay, which diverted the runoff of the seasonal downpours into cisterns or directly onto the fields. Despite this high irrigation effort, farmers produced a wide range of foods during the Roman rule, such as B. barley, wheat, olives and peas. The most important cultivation product of the defense farmers on the Tripolitan Limes was olive oil, which for a long time was only produced for their own use. In the first century AD it became a new export hit and was shipped mainly to Italy. Based on the results of the UNESCO Farming the Desert program, which ran from 1979 to 1981 . The UNESCO Libyan Valleys Archaeological Survey , which was used to research the borderland near the desert that was brought to prosperity by the Romans, tried David Mattingly to determine the annual production volume of olive oil in Roman times. The 262 ancient oil presses known up until 1981 in the Djebel region alone could produce between 1.8 and 2.6 million liters of oil per season, depending on their workload. The introduction of the Roman currency as a means of payment strengthened the power and status of the regional ruling classes and promoted the exchange of goods. In addition, recruits could be recruited from the free peoples.

literature

- Sabine Ziegler, Michael Mackensen: Late antique ostraka from Gheriat el-Garbia (al-Qaryāt al-Garbīyah) in the Tripolitana province (Libya). Evidence for a regional variant of Punic . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department 120, 2014, pp. 313–340.

- René Ployer, Marinus Polak, Ricarda Schmid: The frontiers of the roman empire: a thematic study and proposed world heritage nomination strategy , Vienna, Nijmegen, Munich 2017. PDF .

- Lidiano Bacchielli: La Tripolitania . In Storia Einaudi dei Greci e dei Romani (= Geografia del mondo tardo-antico 20), Einaudi Edition, Milano 2008.

- Graeme Barker , David Gilbertson, Barri Jones, David J. Mattingly (Eds.): Farming the Desert. The UNESCO Libyan Valleys Archaeological Survey. Volume Two: Gazetteer and Pottery . UNESCO, Paris 1996 (et al.), ISBN 92-3-103273-9 .

- Jona Lendering : Sherds from the Desert. The Bu Njem Ostraca . In: Ancient Warfare 1/2, 2007.

- David Mattingly: Tripolitania . University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1994, ISBN 0-472-10658-9 / Batsford, London 1995, ISBN 0-7134-5742-2 / Taylor & Francis, 2005, ISBN 0-203-48101-1 .

- David Mattingly, Martin Sterry, Victoria Leitch: Fortified Farms and Defended Villages of Late Roman and Late Antique Africa . University of Leicester, 2013.

- David Mattingly: Libyans and the 'limes'. Culture and society in Roman Tripolitania . In: Antiquités africaines 23, 1987. pp. 71-94 PDF .

- Erwin M. Ruprechtsberger : The Roman Limes Zone in Tripolia and the Cyrenaica (Tunisia - Libya) , (= writings of the Limes Museum Aalen 47), 1993.

- Egon Schallmayer : The Limes. Story of a border . 3rd edition, CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-48018-8 ,

- Michael Mackensen : forts and military posts of the late 2nd and 3rd centuries on the "Limes Tripolitanus" . In: Der Limes 2, 2010, pp. 20–24.

- Michael Mackensen, Hans Roland Baldus : military camps or marble workshops. New investigations in the eastern area of the Simitthus / Chemtou labor and quarry camp . von Zabern, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-8053-3461-3 .

- Thomas Fischer: The army of the Caesars. Archeology and history . With contributions by Ronald Bockius , Dietrich Boschung and Thomas Schmidts . Pustet, Regensburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-7917-2413-3 ; 2nd, revised and updated edition 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2413-3 .

- Margot Klee: Limits of the Empire. Life on the Roman Limes . Theiss, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-8053-3429-X .

- Edward William Bovill: The Golden Trade of the Moors . 2nd edition, revised and with additional material by Robin Hallett. Oxford University Press, London 1968.

- Christian Witschel : Crisis, Recession, Stagnation? The western part of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century. Chr . (= Frankfurt ancient historical contributions . 4) Marthe Clauss, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-934040-01-2 .

- Christian Witschel: On the situation in Roman Africa during the 3rd century . In: Klaus-Peter Johne, Thomas Gerhardt, Udo Hartmann (eds.): Deleto paene imperio Romano. Transformation processes of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century and their reception in modern times . Steiner, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-515-08941-1 , pp. 145–222

- Peter Heather: The fall of the Roman Empire . 2nd edition, Rowohlt, 2011, ISBN 978-3-499-62665-4 .

- Richard Goodchild : The Limes Tripolitanus II. The Journal of roman studies , Volume 40, Issue 1-2, 1950.

- Richard Goodchild, J. Pedley, D. White: Apollonia, the Port of Cyrene. The University of Michigan Excavations 1965-1967 . Tripoli 1976.

- Richard Goodchild, JB Ward Perkins: The Limes Tripolitanus in the Light of Recent Discoveries . In: The Journal of Roman Studies 39, Parts 1 and 2, 1949.

- Bernd Löhberg: The Itinerarium provinciarum Antonini Augusti. A street directory of the Roman Empire . Textband, Frank & Timme GmbH, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3865962831 .

- Antonino Di Vita, Lidiano Bacchielli, Ginette Di Vita-Evrard: Libya, The lost cities of the Roman Empire . Konemann, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-89508-844-7 .

- Norman Hammond: The Limes Tripolitanus. A roman road in North Africa . IN: Journal of the British Archaeological Association 30, 1967.

- Franz Altheim , Ruth Stiehl: The Arabs in the Old World. Other new finds - North Africa up to the immigration of the Vandals - Du Nuwas , Volume 5, Part 1, de Gruyter, Berlin 1968. (Reprint 2018, ISBN 978-3-11-082575-6 )

- Mario Liverani, Aghram Nadharif: The Barkat Oasis (Sha'abiya of Ghat, Libyan Sahara) in Garamantian Times . The Archeology of Libyan Sahara Volume V. Universita Degli Studi Di Roma “La sapienza”, Department of the Antiques of Libya. 2005.

- Olwen Brogan , Joyce Reynolds : Inscriptions from the Tripolitanian Hinterland . In: Libya antiqua 1, 1964.

- Jocelyn M. Toynbee: Animals in Roman Life and Art . Thames and Hudson, New York 1973. pp. 137-140

- Alain Dierkens: Chameaux et dromadaires en Gaule mérovingienne: quelquesremarques critiques . In: Latomus 279, 2003, pp. 114-137.

- Alain Dierkens: Chameaux et dromadaires dans la Gaule du très haut Moyen-Âge: note complémentaire. La méditerrannée et le monde mérovingien . In: Bulletin Archéologique de Provence , Supplément 3, 2005, pp. 241–245.

- Jacques André: L'alimentation et la cuisine à Rome . Klincksieck, Paris 1961.

- Fabienne Pigièrea, Denis Henrotay: Camels in the northern provinces of the Roman Empire . In: Journal of Archaeological Science 39, 5, 2012, pp. 1531-1539. PDF

- Pat Southern: The Roman Army. A Social and Institutional History . Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0195328783 .

- Raffaele D'Armato: Roman Army Units in the Eastern Provinces (1), 31 BC – AD 195 (= Men-at-Armes 511), Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2017, ISBN 978-1472821768 .

- Christian Körner: Philippus Arabs. A soldier emperor in the tradition of the Antonine-Severan principate (= studies on ancient literature and history 61), de Gruyter, Berlin 2002, ISBN 978-3-11-085783-2

- Hans Weis: The ancient Fezzan. The glacis of the Limes Tripolitanus . In: Annuals of the Austrian Archaeological Institute in Vienna , No. 44, Vienna 1959.

- Rose Mary Sheldon: Intelligence Activities in Ancient Rome. Trust in the Gods but Verify . Routledge, London / New York 2004, ISBN 0415452716 .

Remarks

- ^ Margot Klee 2006, pp. 124-138, Goodchild, Ward-Perkins, p. 81, Norman Hammond 1967, p. 1.

- ^ N. Hammond 1967, p. 1, Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Itinerarium Antonini Iter III.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer 2012, p. 315, Margot Klee 2006, p. 127-138, Bernd Löhberg 2006, p. 95, Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, p. 18., D. Mattingly 1987, p. 82

- ↑ Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, p. 12.

- ↑ Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, p. 12ff

- ↑ Margot Klee 2006, pp. 135-136, Bernd Löhberg 2006, p. 95, Goodchild, Ward-Perkins, 1949 p. 81, Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, p. 14.

- ↑ Olwen Brogan, Joyce Reynolds 1964, pp. 43-46; here: pp. 43-44, David Mattingly 1994, p. 99, AE 1992, 01761 .

- ↑ Inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania: IRT 880 (with photos and drawings) , accessed January 29, 2019.

- ↑ a b Sabine Ziegler, Michael Mackensen : Late antiquity ostraka from Gheriat el-Garbia (al-Qaryāt al-Garbīyah) in the province of Tripolitana (Libya). Evidence for a regional variant of Punic . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department 120, 2014, pp. 313–340; here: p. 334.

- ^ A b Michael Mackensen: The Severan vexillation fort Myd (---) and the late antique settlement in Gheriat el-Garbia (Libya). Report on the campaign in spring 2010 . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department 117, 2011, pp. 247–375; here: p. 249.

- ↑ CIL 08, 22765 .

- ↑ Margot Klee 2006, pp. 126-137, Johne, Gerhardt, Hartmann 2006, p. 150, David Mattingly, 2005, p. 130, Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Sabine Ziegler, Michael Mackensen: Late antique ostraka from Gheriat el-Garbia (al-Qaryāt al-Garbīyah) in the Tripolitana province (Libya). Evidence for a regional variant of Punic . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department 120, 2014, pp. 313–340; here: p. 332.

- ↑ Sabine Ziegler, Michael Mackensen: Late antique ostraka from Gheriat el-Garbia (al-Qaryāt al-Garbīyah) in the Tripolitana province (Libya). Evidence for a regional variant of Punic . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department 120, 2014, pp. 313–340; here: pp. 332–333.

- ↑ Sabine Ziegler, Michael Mackensen: Late antique ostraka from Gheriat el-Garbia (al-Qaryāt al-Garbīyah) in the Tripolitana province (Libya). Evidence for a regional variant of Punic . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department 120, 2014, pp. 313–340; here: pp. 332–333.

- ↑ Sabine Ziegler, Michael Mackensen: Late antique ostraka from Gheriat el-Garbia (al-Qaryāt al-Garbīyah) in the Tripolitana province (Libya). Evidence for a regional variant of Punic . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department 120, 2014, pp. 313–340; here: pp. 315-316; here: p. 318.

- ↑ Sabine Ziegler, Michael Mackensen: Late antique ostraka from Gheriat el-Garbia (al-Qaryāt al-Garbīyah) in the Tripolitana province (Libya). Evidence for a regional variant of Punic . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department 120, 2014, pp. 313–340; here: p. 335.

- ^ Procopius: De Aedificis, VI, 3.

- ↑ Res Gestae 26, 4, 5. , Bernd Löhberg 2006, p. 95, R. Plidori 1999, p. 228-233, Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, p. 16-18, D. Mattingly 1987, p. 88ff, Synesius, Catastasis I, 1568; cf Id., letters, 78.

- ↑ Bernd Löhberg 2006, p. 95

- ↑ AE 1993, 01709 .

- ↑ Egon Schallmayer 2011, p. 30, Margot Klee 2006, pp. 144-145, Michael Mackensen 2005, p. 77, Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, p. 15, David Mattingly 1987, p. 82, Christian Körner 2002, p. 247 .

- ↑ Pat Southern 2007, p. 123, Pliny, Nat. Hist., XI, 237; XXVIII, 123, A. Dierkens 2003, pp. 114 to 117 and 2005, pp. 241-245; J. Toynbee, 1973, pp. 137-140, André, 1981, p. 140, Christian Witschel 1999, p. 197.

- ↑ Altheim, Stiehl 1968, pp. 215-216, Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, p. 15, David Mattingly 1987, p. 91.

- ↑ Notitia dignitatum, occ. XXV, Comes Africae, Peter Heather: 2011, p. 313, Notitia Dignitatum, Occ. XXI (Dux provinciae tripolitanae), Witschel 2006, pp. 145-222; here: pp. 184-186, Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, p. 16.

- ↑ Michael Mackensen 2010, pp. 20–24; here: p. 22

- ↑ Margot Klee 2006, pp. 141-143.

- ↑ Margot Klee 2006, p. 140.

- ↑ AE 1991, 1621 , Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, pp. 23 and 100, David Mattingly 2005, pp. XVII – XVIII.

- ↑ Michael Mackensen: The Severan vexillation fort Myd (---) / Gheriat el-Garbia on the "limes Tripolitanus" (Libya). Report on the 2009 campaign . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department 116, 2010, pp. 363–458; here: p. 368.

- ↑ CIL 08, 00003 .

- ↑ Erwin Ruprechtsberger 1993, p. 22, RM Sheldon 2004, p. 167.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer 2012, p. 315, Margot Klee 2006, pp. 143–144, E. Ruprechtsberger 1993, p. 22.

- ↑ D. Mattingly 2013, pp. 1-2, D. Mattingly 1987, pp. 84 and 87.

- ↑ Bernd Löhberg 2006, pp. 82 and 95, Goodchild, Ward-Perkins, p. 81.

- ^ Margot Klee 2006, p. 146, David Mattingly 2005, pp. XVII – XVIII and 1987 p. 90f.

- ↑ a b D. Mattingly 1987, p. 83.

- ^ Erwin M. Ruprechtsberger : The Roman Limes Zone in Tripoliania and the Cyrenaica (Tunisia - Libya) , (= Writings of the Limes Museum Aalen 47), 1993, p. 26.