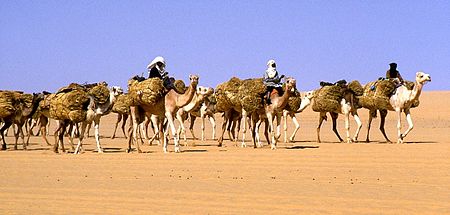

Salt caravans in the Sahara

The salt caravans in the Sahara serve to exchange goods between regions of the Sahara and the Sahel zone . Dromedaries are used as a means of transport . There are essentially two caravan routes that are still frequented today, one between Timbuktu and Taoudenni in Mali and the second in Niger , between Agadez or the southern Aïr Mountains and the oases of the Ténéré , Fachi and Bilma . The third salt oasis, Séguédine , to the north of the Ténéré, is too remote to play a role. In Tamaschek , the salt caravan between Timbuktu and Taoudenni is known as Azalaï , while that in Ténéré is called Taghlamt (or Tarhalamt ).

history

Since the Middle Ages, there has been evidence of a flourishing exchange of goods within the Sahara and its peripheral areas, with salt playing a key role. The historian Abū ʿUbaid al-Bakrī in the 11th century and the Berber explorer Ibn Battuta , who traveled the region between 1351 and 1353 and visited one of the salt metropolises with Taghaza , described the abundant turnover of goods.

The printer and translator Valentim Fernandes Alemão, a native German from Moravia, described in Portugal in 1500 the caravan trade with rock salt plates from 300 km north of Chinguetti in Mauritania located Idjil that even then Terhazza el Gharbie was "Western Taghaza" called. Its exceptionally good salt made its way to the western Trans-Saharan trade route , which led from Sijilmasa in Morocco via Tamdoult and Ouadane to Aoudaghost .

Numerous Arabic travel reports since the 10th century and later European travel reports on the salt and gold trade in West Africa adorn historical facts with fantastic elements and describe the exchange of goods as silent trade . In the early to mid-16th century, the Arab geographer Leo Africanus gained extensive impressions of the caravan trade, which he passed on in his Descrittione dell'Africa (Description of Africa) , which has been the standard work for centuries .

Salt mining centers in the Sahara

Idjil in Mauritania

In 1933, Capitaine Brosset described the Idjil salt mine, which is near the present-day town of F'dérik . The surroundings of Idjil with pastures and wells and the fact that the salt layers begin under a cover layer only 1 meter thick made salt mining easier for the Moorish Azarzir . The rock salt , which is very pure with 94% NaCl , is beaten in the form of trapezoidal bars weighing 20 to 40 kg and is mainly offered in Atar , Chinguetti, Ouadane, Tidjikja and Ayoûn el-Atroûs . Because of the competition from the sea salt , which can be produced cheaply by Kaolack in the Senegalese salt pans , the previously coveted Idjil rock salt has been increasingly displaced from the market.

Taoudenni in Mali

In the Taoudenni salt mine, 700 km north of Timbuktu, mostly bonded workers work in open-cast mining with primitive hoes in pits up to 4 m deep from the rock salt layers, about 125 cm × 50 cm in size. An ingot called adile weighs about 30 kg when fully hewn. The daily norm is the production of 4 panels per worker. Before the three high-quality rock salt layers are reached - the deepest is the best (two of the salt slabs can be hewn from its layer thickness and that of the second best) - a 1.50 m thick cover layer of clay and some inferior salt layers must first be removed become. This means that the spoil is roughly forty times the volume of salable salt. If a pit is exploited, another is dug - on an open area between the overburden mounds - so that there are now thousands. In the winter of 2007/2008 around 1000 men are said to have worked in teams of three in the pits - almost all of them leave Taoudenni in the summer months after the mining season, which lasts from October to April. A caravan needs twenty days to travel to Timbuktu.

Amadror in Algeria

Also in the gravel plain of Amadror, northeast of the Hoggar in Algeria , near the "ghost mountain " called Gara el Djenoun , there is a rock salt deposit that used to be of central importance for the Kel Ahaggar - Tuareg . The old In-Taouia mine had massive rock salt layers similar to those in Taghaza and Taoudenni; At the site, Agajer , which was used from 1900 onwards , the caravan people could relatively easily remove the approximately 15 cm thick layer of rock salt under a thin layer of sand. In the Tuareg language , the mining site is also called Tissemt ("salt"). After the salt mining in July / August, the caravans moved in September / October to the pastureland of the Tamesna ("plain") northwest of Agadez in Niger and later on to the markets of Tahoua or Zinder . In February / March, after returning from the Sahel , they exchanged part of the millet they had received there for dates in the oases irrigated by Foggaras near In Salah in the Tidikelt plain. When the regulation of the Tuareg increased after Algerian independence in 1962, the Amadror caravans almost came to a standstill.

Tegguida-n-Tessoum in Niger

The salt extraction in Tegguida-n-Tessoum (north of Ingal ) requires enrichment processes due to the relatively low salt content of the salt earth: In a basin about two meters in diameter, salt earth and salt spring water are mixed by tamping. After the sludge has settled, the brine is scooped into a second basin of almost the same size and concentrated through evaporation. The concentrate is then distributed in ten to twenty surrounding basins about 30 cm in diameter, in which the water evaporates completely until a reddish layer of salt crystals remains. The salt formed into plates of different sizes finds its way and a. to the salt markets of Ingal and Agadez .

Fachi and Bilma in Niger

The most important Nigerian salt producers are the Fachi and Bilma salt pans . Saturated brine emerges there. The gray-yellow kantu, which are produced in the shape of a cone as cattle salt and weigh around 25 kg, are reminiscent of slightly oversized traffic pylons . The shape stems from the fact that hollowed out palm stalks serve the saltworkers as casting molds for drying the salt. Another product form of the salt from Fachi and Bilma are the so-called fotschi ( foschi ), loaves of salt formed by women in enamel bowls, which weigh up to approx. 2 kg and usually consist of beza , crystallized, relatively pure salt that is used as table salt . About three quarters of the salt production is made as kantu , a quarter as beza salt.

Salt caravans in Niger

Triangular trade between the Sahara and the Sahel

The salt caravans through the Ténéré are an expression of a centuries-old inter-ethnic economic system that includes the Tuareg, Kanuri and Haussa . The "motor" of this system is the need for salt for the animals of the ranchers in the Sahel. Tuareg draw z. B. from Aïr to Fachi and Bilma. In addition to the most important commodity, millet from the previous caravan tour, the caravans also bring small quantities of other goods to the salt oases, depending on their origin. This includes meat or small livestock, fat, cheese, luxury goods such as tea, sugar and cola nuts, as well as industrially manufactured goods. The Kanuri swap all of this for dates and salt. With the goods they received (bags of dates are ideal for cushioning the bulky loads of salt) they move further south to the Haussa Sahel markets, as far as Kano in Nigeria , where they can now receive money and millet for salt and dates. Finally they return to the Aïr, where the triangular trade can begin again.

Importance of the caravans for Fachi and Bilma

The salt caravans are of vital importance to Fachi and Bilma. They bring millet, the staple food of the oasis dwellers, who could not survive without this bread grain. In addition, the camel dung left behind is the most important fuel. The caravans are also important as news transmitters and as a means of travel.

Travel preparations

The salt caravans of the Tuareg are extremely lengthy, exhausting and hard-working trade ventures that require enormous perseverance. A mystification as a fairytale-romantic "travel trip" in the silence of desert seclusion, which can be found variously in western media, misjudges the actual conditions.

The caravan trade requires extensive preparations, such as the compilation of large supplies of dry grass for the dromedaries. Ropes of all kinds are made for their diverse functions as load and guide ropes, packing nets and muzzles. Furthermore, scoop ropes are knotted so that water can be drawn from the planned water holes and wells. Water hoses are filled and various sewing work is carried out on the goat leather load bags, load bars are manufactured and planned.

Caravan cycle

Caravans usually take place in the winter months from October to January. You will e.g. B. compiled in the nomad camps of the Aïr Mountains. Dromedaries, cargo and companions are placed under the responsibility of the Madugu . In addition to the experienced caravaners, even small boys gain their first experience as accompanying "apprentices". Women and girls do not take part in these activities.

Caravan groups

A caravan group includes up to 50 pack animals. About eight animals are looked after by one man at a time. Individual caravan groups only connect loosely on the route - depending on the terrain and the discipline in the respective association. Usual caravans consist of 50 to 300 animals. In the past there were also huge caravans - to protect against raids - in which up to 25,000 dromedaries took part.

The caravan entrepreneurs

There are various groups that operate as caravan operators. In Fachi a distinction is made between caravans from the west, which are mainly carried out by Kel Aïr-Tuareg from the Aïr massif (such as the Kel Ewey from the area around Agadez. Timia and Iferouane ), and "southern caravans" from Kel Gress-Tuareg and their former slaves (Buzu and Musugu), who, strictly speaking, come from the southwest: their home is the Sahel in southern Niger. The Daza, Aza and Manga caravans make up only a small part of the salt caravans.

Caravan routes

The formerly extensive networks of the routes are only used to a very limited extent today. From a historical perspective, this "shortening" of road use is due to different influences. The French colonial times, tribal feuds and rebellions, drought disasters in the Sahel and malaria dangers (see Djado ) are part of it.

The main route in the north-south course is the Bornus road from Murzuk in Fezzan in Libya via Séguédine to Bilma and Lake Chad .

The main route in the west-east course leads from Agadez via Fachi to Bilma . It forms nodes to northern Nigeria (where goods such as tea and fabrics are exchanged for salt) and to the eastern Sahara - there in the remote Tibesti region of Chad or in the southern course in Sudan .

In Mali, a caravan route connects Timbuktu and Taoudenni .

Descriptions

In his book Salt Caravans in the Sahara, which he researched in the 1970s, the ethnologist Hans Ritter describes the salt pans in Fachi and Bilma as well as the other Nigerian salt spring , Tegguida-n-Tessoum , the Algerian salt mine Amadror , the "cities made of salt", Taghaza and Taoudeni in Mali, as well as the Sebkha of Idjil in Mauritania. The work also contains a detailed map of the trade routes and salt routes from Mauritania to the Tibesti. Hans Ritter has also published an extensive dictionary on the language and culture of the Tuareg, which also focuses on the salt trade and caravan economy.

See also

literature

- Al-Bakrî: The geographical dictionary = Kitab al-Mu'djam masta'djam. Edited and translated into German by Ferdinand Wüstenfeld. Göttingen 1876–1877 (Reprint: Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-8298-1197-7 )

- Ibn Battuta : The wonders of the Orient. Travels through Africa and Asia. Translated into German from the Arabic edition by Muhammad al-Bailuni, with comments and an afterword by Ralf Elger. Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60068-5

- Maximilien Bruggmann (photos), Hans Ritter (text): Ténéré. Through the southern Sahara . Verlag CJ Bucher, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-7658-1078-9

- Alexis Épaulard, Henri Lhote , Théodore Monod (eds.): Description de l'Afrique . Edition Maisonneuve, Paris 1980. (2 volumes, reprint of the 1958 edition, French)

- Peter Fuchs: The bread of the desert. Socio-economy of the Sahara. Steiner, Wiesbaden / Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-515-03764-0

- Werner Gartung: The salt caravan: with the Tuareg through the Ténére. Reise-Know-How-Verlag Hermann, Markgröningen 2000, ISBN 3-89662-309-5

- Horst Jürgen Grün (ed., Translation): The journeys of Ibn Battuta. 2 volumes. Allitera-Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-86520-229-1 and, ISBN 978-3-86520-230-7 . (First German translation of the complete works)

- Michael Martin : The deserts of Africa . 2nd Edition. Frederking & Thaler, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-89405-382-8

- Dietrich Zigarrenberger (Ed.): Johannes Leo the African. His description of the space between the Nile and Niger according to the original text. (Orientalia biblica et christiana 13) Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-447-04172-2 . (Relevant scientific edition)

- Karl Schubarth-Engelschall (ed.); Johann Leo Africanus: Description of Africa. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1984, DNB 850079969 . (incomplete popular edition, but published by one of the best experts in Islamic research on Africa)

Web links

- edition.cnn.com: Searching for 'white gold' in the 'cruelest place on Earth' ("In search of" white gold "in the" most ruthless place on earth "", for salt production and salt caravan in the Afar triangle, Ethiopia)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Werner Gartung: Tarhalamt. The Kel Ewey salt caravan. Museum für Völkerkunde, Freiburg im Breisgau 1987, ISBN 3-923804-15-6 .

- ^ Salt - a sought-after mineral for thousands of years. Planet knowledge .

- ↑ Capitaine Brosset: La saline d'Idjil. In: Bulletin du Comité de l'Afrique française. Vol. XLIII, No. 11, Nov. 1933.

- ↑ Barbara Rocksloh-Papendieck, Henner Papendieck: Log of a trip from Timbuktu to Taoudeni December 23-28, 2007. GTZ / KfW , p. 7: Debt bondage, photos: p. 4, 6 (PDF; 871 kB).

- ↑ Photo of the clay and salt layers in a mine pit near Panoramio .

- ^ B. and H. Papendieck: Log of a trip from Timbuktu to Taoudeni, p. 12: Photo laden dromedaries.

- ↑ Photo of the Day, February 11, 2012: Caravanner and Camels, Mali. National Geographic .

- ↑ Photo: Morning loading of the dromedaries with the salt bars. Xinhua.net ( Memento from January 1, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ).

- ↑ Les Salines de l'Amadror. JournalDuTrek.com, October 23, 2007 (French).

- ^ Geographic features & Photographs around Tissemt, in Algeria (general), Algeria. TravelingLuck.com.

- ^ Map of the Tidikelt

- ↑ Photos of the salt pans in Tegguida-n-Tessoum

- ↑ Werner Gartung: The salt caravan. With the Tuareg through the Ténéré. Reise Know − How Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-89662-380-X .

- ^ Salt caravan in the Ténéré. Photo from: George Steinmetz : Deserts from above. Frederking & Thaler, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-89405-965-1 .

- ↑ Hans Ritter: Salt caravans in the Sahara. Atlantis-Verlag Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7611-0580-0 .

- ↑ abload.de: Map of the salt roads and trade routes

- ↑ Hans Ritter, Karl G. Prasse: Dictionary of the language and culture of the Twareg. Part 2, Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-447-05887-2 .