Tuareg

The Tuareg ( singular : Targi (male), Targia (female); for this name, see the Etymology section ) are a Berber people in Africa whose settlement area extends over the Sahara desert and the Sahel .

Of the Tuareg in addition to their will own language more traffic languages spoken by Songhai about Arabic and Hassania to French ; their script is the Tifinagh . For centuries they lived nomadically in what is now Mali , Algeria , Niger , Libya and Burkina Faso . Since the middle of the 20th century, many have now settled down . They count, with strongly fluctuating information about 1.5 to 2 and according to self-information up to 3 million people.

In recent years there have been repeated uprisings by the Tuareg, who feel prevented from continuing their nomadic pastoral way of life .

etymology

The word Tuareg is derived from the word Targa , the Berber name for the Fezzan province in Libya. This is what the Tuareg originally used to describe the inhabitants of Fezzan. Targa is a Berber word that can be translated with 'gutter' or 'canal', in the broadest sense also with 'garden'. According to local opinion, Targa does not refer to the whole of Fezzan, but only to the region between the cities of Sebha and Ubari and is called bilad al-khayr 'good land' in Arabic . This means the fertile Wadi al-Haya (formerly Wadi al-Ajal), which supplies the entire south of Libya with agricultural products.

The Arabic folk etymology, which is widespread to this day : Tawariq (singular: Tarqi ), 'the people forsaken by God', is used to express an Arab superiority over the Tuareg. The reason for this is the liberal religious views of the Tuareg, who are regarded as reprehensible by representatives of strict Muslim doctrine.

The name Tuareg has been naturalized in the German, Francophone and Anglo-American language areas since the colonial era. The Tuareg themselves do not use this name. The emic name of the Tuareg is Imajeghen in Niger, Imuhagh in Algeria and Libya and Imushagh in Mali. The gh is pronounced like the German Rachen- r and the emphasis is on the first syllable. This self-denomination ( endonym ) refers to people of free descent who have noble qualities. This refers to the code of honor (asshak) of the Sahara and Sahel inhabitants. All three terms go back to the same root and are only different because of the dialectal form. In addition to this own name Imajeghen / Imuhagh / Imushagh, the name Kel Tamasheq, 'the people who speak Tamasheq', is used.

In the literature, the Tuareg are referred to as Kel Tagelmust 'the people of the face veil' or "the blue people" because they wear clothes dyed with indigo . Both terms are not used by the Tuareg.

history

The Tuareg are a Berber people . They are said to be descendants of the old Berber Garamanten who developed a warlike camel nomadism around the turn of the times in the regions of what is now southern Tunisia and Libya . In the 11th century they were expelled from the Fessan by Arab Bedouins from the tribe of the Banū Hilāl and withdrew to the areas of the central Sahara , especially the Tassili n'Ajjer, Aïr and Ahaggar, where they have lived since that time. To that extent, they were able to evade the Arabization of their culture (writing, language, craft culture, matrilineal social structures). Nevertheless, they adopted Islam. With this displacement they in turn drove the desert people of the Tubbu into the Tibetan Mountains . After the fall of the Songhai Empire in the course of the Moroccan war of conquest in the 16th century, the Tuareg increasingly invaded the Sahel and subsequently gained control of Timbuktu and the Sultanate of Aïr based in Agadez .

The Tuareg had to fight again and again for the right to be recognized as a free people and to be allowed to live according to their tradition . For a long time in the 19th century they offered violent resistance to the advancing colonial power France in the Sahara zone of West Africa . A peace treaty was not concluded until 1917. With the end of French colonial rule in West Africa in 1960, the Tuareg settlement area was divided between the now independent states of Mali, Niger and Algeria, with smaller groups of Tuareg also living in Libya and Burkina Faso . From 1990 to 1995 the Tuareg revolted in Mali and Niger due to the repression and marginalization by the respective governments. A leader of the Tuareg uprising was Mano Dayak . In the mid-1990s, the uprisings ended after the peace treaties were signed. In 2007, the newly formed Tuareg rebel group, Movement of the Nigerien for Justice, accused the government of violating the peace treaty. They are also demanding a share of the profits from the uranium mining northwest of Agadez for the Tuareg (uranium mine near Arlit ).

As a result of the civil war in Libya in 2011, the security situation in northern Mali worsened after Tuareg who fought on the side of Muammar al-Gaddafi were expelled from Libya. The armed groups acting as the National Movement for the Liberation of the Azawad (MNLA) invaded Mali via Niger from the end of 2011 and took control of areas in the north of the country. Whether they have any connection to Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb is a matter of dispute. Malian soldiers accused President Amadou Toumani Touré's government of being unable to fight the Tuareg uprising in the north of the country and took power in a coup in March 2012 . The MNLA took advantage of the situation and captured all the cities in the Azawad area in the following days up to the beginning of April . On April 6, it unilaterally proclaimed the independent state of Azawad.

Main places

As a nomadic people who were divided into several political confederations until the colonial era , the Tuareg have no capital. Agadez in Niger, with the seat of the Sultan of Aïr, can best be described as a central place. For the northern Tuareg ( Kel Ajjer and Kel Ahaggar ), the southern Algerian oasis Djanet and the southern Libyan oasis Ghat played a similar role in earlier times. The current capital of the Ahaggar Mountains, Tamanrasset , did not emerge until after 1900, when the French missionary Charles de Foucauld settled in the area. Only after the final conquest of the mountains by the French colonial troops did the place grow and become the official seat of the amenokal (king) of the Kel Ahaggar.

Culture and religion

The culture of the Tuareg was researched and described in detail by the African researchers Heinrich Barth and Henri Duveyrier .

Since the first wave of Islamic migration by the Umayyads from the peninsula to North Africa, the Maghreb and Egypt have been Arabized. The Tuareg were the trade routes to Muslims , although they initially strongly against a missionary resisted, because the Islam spreading Arabs were their traditional enemies. Today, Islam among the Tuareg is based on the Malikite doctrine (like almost all of North Africa) and they belong to various brotherhoods . Most of them strictly adhere to the rules of Islam. They were able to incorporate their belief in good and bad spirits (Kel Essuf) into the Muslim religion, since Islam also mentions the presence of spirits in the Koran . To defend them, amulets , magical symbols wrapped in leather, are indispensable. The women wear the chomeissa, an abstract form of the hand of Fatima , as amulet jewelry .

As in the entire Sahel region, drinking tea ceremonially is an important part of everyday culture. There are three different strengths of infusions. A guest who has finished three glasses is under the protection of the Tuareg.

The Tuareg were originally purely nomadic cattle breeders with a complex hierarchical social model:

- Imajeghen / Imuhagh / Imushagh

- Imaghad

- Iklan (Iderafan, Ikawaren, Izzegharen)

- Inadan

- Ineslimen

Today only a few groups are fully nomadic. Most of them live from semi-nomadic, mobile pasture farming with partial connection to market economy structures.

Some tribes held political and economic power until the colonial conquest. They provided the king , the amenokal . There are also immigrant tribal groups, which are described in the literature using terms of feudal Europe, the Imaghad. In pre-colonial times they had to deliver taxes, but they cooperated in political matters with the Imajeghen / Imuhagh / Imushagh and were protected by them. Iklan, “slaves”, played an important economic role in the traditional system. They represented the property of one family, but were integrated as fictional relatives. Slaves could be released and were then referred to using different terms (including Iderafan, Ikawaren, Izzegharen ). The artisans and blacksmiths (Inadan) represent their own social group, who are considered to be people without shame or decency, but were indispensable for the economy, as they made tools, tools, weapons, kitchen utensils and jewelry. For the sake of completeness, the Ineslims , the Koran scholars, are mentioned, although the term refers to all Muslims.

This social system still plays a role today and assigns values and moral concepts to the respective classes, which the individual group members must adhere to

The woman welcomes the guests and supervises the preparation of the tea. She decides who to marry and she can cast her husband away. Divorce is not a shame in this culture. Likewise, she is allowed to have had different lovers before marriage. After a divorce, the children stay with the woman. The sons of the sister are preferred by men in the passing on of their possessions, as one assumes a closer connection here than is the case with their own sons. One speaks here of matrilinearity , which does not mean matriarchy .

The lost or sunken oasis of Gewas is an important symbol in the Tuareg culture . It stands for the longing for a perfect, paradisiacal world full of riches and abundance. This imaginary alternative to the merciless and barren reality of the desert serves as a kind of consolation. In the mind of the Tuareg, this legendary place can only be found by those who do not consciously and specifically look for it.

With the Tifinagh , the Tuareg have a writing system that is not used for everyday communication. In earlier times, too, knowledge of the Tifinagh was limited to the “noble clans” (that is how the Imajeghen / Imushagh / Imushagh are referred to in older literature), where it was taught to the children by their mothers or the old women. Today, many artisans use the Tifinagh script and engrave their names on jewelry they have made themselves.

→ Article: History of Islam among the Tuareg

Living

The wandering Tuareg live in tents. The tribes of the Sahel zone build their mat tents from palm fronds . When the tribes stay in one place for a long time, they establish seribas . These small huts made of reed have two entrances, which provide passage. A straw mat, called asabar , which is placed in front of the entrance, serves as a windbreak . In the desert, the Tuareg have leather tents made from 30 to 40 sheepskins and goat skins . When setting up the tents, they first set up the arched structure, then the furniture is placed and then the roof and side walls are thrown over them and covered. Many of the Tuareg have moved to the cities. Others have built their own settlements on oases and practice arable farming . Most Tuareg who want to start a new life in a city go to Agadez, a city in Niger where many of them already live.

dress

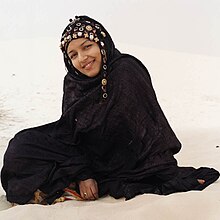

The clothing of the nomads is gender specific. Men wear black trousers (ikerbey) embroidered at the hem with white or yellow threads , a long overgarment reaching to the ankles (tekatkat) and a face veil, tagelmust or eshesh , to cover their mouths, since body orifices are considered unclean. It is also common for men to veil themselves in front of women. According to another interpretation, the men who frequently travel in the desert and in the mountains must protect themselves from the Kel Eru , the spirits of the dead, who try to take possession of the living by their mouth. A high hat made of red felt, which was called a tukumbut , was part of the traditional male costume, at least on high holidays . As with the Berbers, the face of the women is uncovered, but they wear a scarf on their heads that shows their dignity and honor as a grown woman. The headgear of men and women primarily has to do with the society's code of honor (asshak) and expresses respect, decency and reserve (takarakit) .

Women are dressed in a wrap skirt (teri) and a loosely fluttering, elaborately embroidered top (aftaq) or wear a wrap robe (tasirnest). Like the daily must of men, women have a head covering, adeko or afar, that underlines their honor and dignity and emphasizes being a woman.

The headgear of the Tuareg is based less on Muslim norms than on their own values (cf. Rasmussen 1995). It also offers protection from sun, sand and wind and reduces body dehydration. Aleschu , the piece of fabric dyed indigo blue and sewn together by hand from many lengths of fabric, is the trademark par excellence, but was first imported from Kano into the Tuareg region almost 150 years ago (Spittler, 2008). Years of wear give the skin a bluish tint, hence the cliché of the “blue knight of the desert”. Fine muslin fabrics in white or black have also been in use for about a century (eschesch), as the increasing impoverishment meant that the aleschu was no longer affordable. The Chèche (also spelled Schesch ) is between 2.5 meters and 15 meters long, depending on whether it is a young man or a respectful older person.

nutrition

Various types of grain that are grown or gathered by the women and from which they make the Tuareg bread, taguella , form the basis of the diet. Millet is mainly used in the south, wheat and barley in the north . Camel milk is important for the wandering Tuareg . It is drunk uncooked with water with the daily meal. In gedḥān mentioned wooden bowls allowed to stand open, they fermented to sour milk or sour milk. They also need goat, cow and sheep milk for butter and cheese. When the Tuareg are on the move , the taguella is part of the diet (especially in Algeria). Meat is usually only available at religious and family festivals. The Tuareg often disdain eggs, chickens and fish. Berries, fruits, roots and seeds are gathered like grain by the women and children. The green tea introduced by the Arabs has become almost indispensable for the Tuareg. The ritual of making tea is part of the tea culture of North West Africa .

Music and parties

There are several traditional styles of music, for example tendé , imzad and donkey. Tendé is also known as the "dance of the camels". The women sit close together and sing a cantor drumming on the covered with goatskin millet mortar, which tends is called, and the men circle the women on their camels. Imzad is a single-string fiddle that is preferably played by older women. The three-stringed Tuareg lute Tahardent is similar to the four -stringed tidinite of Mauritania, it has spread in the cities on the edge of the desert since the 1960s. Esele is a kind of "desert disco" in which young women invite men to dance with rhythmic singing and clapping hands. Guitar music is very popular. A festival without a guitar is unthinkable in some regions.

Weddings and national or religious annual festivals are of great importance in the life of the nomads. The biggest celebration is the wedding. Men and women wear this noble clothes, plus there is a music usually tends. So is also another festival in which the type of music exclusively tend played. There are also many regional festivals.

In Djanet in southern Algeria every year before the Islamic Ashura tag the ten-day Sebiba - organized dance festival. Bianou is a similar New Year celebration that takes place in Agadez in northern Niger.

Arts and crafts

The Tuareg forge a wide variety of objects from iron , silver and non-ferrous metals, from weapons to earrings . Nowadays, they primarily extract iron from industrial scrap , for example half-axles from off-road vehicles, which they then process into axes. For the production of objects made of non-ferrous metal (copper, brass and bronze), the lost wax process is mostly used, in which a model of the desired object is first made from wax. The model is then hardened in cold water and then covered with fine clay . Several holes are left free so that the wax can later be melted out. Now the clay is heated and the wax is poured through the openings into a bowl of water for recycling. The intended metal has already been melted in a clay crucible (tebent) . When the cast metal is hot enough, it is poured into the clay mold through the wax pouring hole. This is smashed after the metal has hardened, then the cooled blank is filed and polished (for example with sand) and a pattern is scratched. Since no prefabricated casting molds are used for brass , the unprocessed objects are very different.

trade

With their camels, the Sahara Tuareg bring salt from the Amadror plain and other places, as well as dates to various markets. With the proceeds they buy grain, fabrics, tea and sugar. The Sahara Tuareg could not live without this caravan trade. It is run only by the men, so that the women are sometimes left alone with the children and the herds for months. The Sahel Tuareg trading companies limit themselves to selling their cattle.

Well-known Tuareg

- Attaher Abdoulmoumine (* 1964), Nigerien paramilitary leader and politician

- Rhissa Ag Boula (* 1957), Nigerien paramilitary leader and politician

- Hamid Algabid (* 1941), Nigerien politician, Prime Minister of Niger

- Habibou Allélé (1938–2016), Nigerien politician and diplomat

- Mouma Bob (1963–2016), Nigerien guitarist and singer-songwriter

- Bombino (* 1980), Nigerian guitarist and singer

- Aïchatou Boulama Kané (* 1955), Nigerien politician

- Akoli Daouel (* 1937), Nigerien politician, journalist and entrepreneur

- Mano Dayak (around 1950–1995), Nigerien political activist, entrepreneur and writer

- Rissa Ixa (* 1946), Nigerien painter

- Sanoussi Jackou (* 1940), Nigerien politician

- Mdou Moctar (* 1985), Nigerien guitarist and singer-songwriter

- Abdallah ag Oumbadougou (* around 1962), Nigerien musician

- Brigi Rafini (* 1953), Nigerien politician, Prime Minister of Niger

- Jeannette Schmidt Degener (1926 / 1927–2017), Nigerien entrepreneur and politician

- Ilguilas Weila (* 1957), Nigerien abolitionist

- Mouddour Zakara (1912–1976), Nigerien politician

- Ikhia Zodi (1919–1996), Nigerien politician

See also

literature

- Henrietta Butler: The Tuareg: The Tuareg, or Kel Tamasheq. And a History of the Sahara. Gilgamesh Publishing, 2015

- Edmond Bernus, Jean-Marc Durou: Touaregs - un peuple du désert. Robert Laffont, Paris 1996.

- Mano Dayak : The Tuareg Tragedy. Bad Honnef 1996. ISBN 978-3-89502-039-1 .

- Henri Duveyrier : L'exploration du Sahara. Les Touaregs du Nord. Paris 1864.

- Harald A. Friedl: Culture shock Tuareg. Travel know-how. Peter Rump, Bielefeld 2008. ISBN 978-3-8317-1608-1 .

- Harald A. Friedl: trips to the desert knights. Ethnic tourism among the Tuareg from the perspective of applied tourism ethics. Traugott Bautz Verlag, Neuhausen 2009

- Werner Gartung: Tarhalamt. The salt caravan of the Kel Ewey Tuareg. Museum für Völkerkunde, Freiburg im Breisgau 1987 ISBN 3-923804-15-6 .

- Werner Gartung: Got through. 1000 kilometers of desert with the Tuareg salt caravan . Pietsch Verlag, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-613-50049-3 .

- Gerhard Göttler: The Tuareg. DuMont, Cologne 1989. ISBN 978-3-7701-1714-7 .

- Claudot-Hawad Hélène: Honneur et politique: Les choix stratégiques des Touareg pendant la colonization française. In: Encyclopédie Berbère. Volume XXIII. Aix-en-Provence 2000. pp. 3489-3501.

- Jacques Hureiki: Tuareg - healing art and spiritual balance. Cargo Verlag, Schwülper 2004. ISBN 978-3-9805836-5-7 .

- Herbert Kaufmann : Economic and social structure of the Iforas Tuareg. Cologne 1964 (Phil. Diss.).

- Jeremy Keenan: The Tuareg. People of Ahaggar. Allan Lane, London 1977. ISBN 978-0-312-82200-2 .

- Georg Klute, Trutz von Trotha: Paths to Peace. From guerrilla warfare to para-state peace in the north of Mali. In: Sociologus. No. 50, 2000. pp. 1-36.

- Ines Kohl: Tuareg in Libya. Identities between borders. Reimer, Berlin 2007. ISBN 978-3-496-02799-7 .

- Peter Kremer, Cornelius Trebbin: Tuareg - lords of the desert. Supplement to the exhibition of the Heinrich Barth Society. Cologne, Düsseldorf 1988. ISBN 978-3-9801743-0-5 .

- Thomas Krings, Sahel countries, WBG country customers, 2006, ISBN 3-534-11860-X

- Henri Lhote : Les Touaregs du Hoggar. Paris 1955 (two-volume reprint 1984 and 1986). ISBN 978-2-200-37070-1 .

- Johannes Nicolaisen: Economy and Culture of the Pastoral Tuareg. Copenhagen 1963 (important study on a structuralist basis).

- Thomas Seligman and Krystine Loughran (Eds.): Art of Being Tuareg: Sahara Nomads in a Modern World. Los Angeles 2006, ISBN 978-0-9748729-6-4 .

- Hans Ritter: Dictionary on the language and culture of the Twareg. Volume I: Twareg-French-German. Elementary dictionary with an introduction to culture, language, script and dialect distribution. Wiesbaden 2009. ISBN 978-3-447-05886-5 . Volume II: German Twareg. Wiesbaden 2009. ISBN 978-3-447-05887-2 .

- Edgar Sommer : Kel Tamashek - The Tuareg Cargo Verlag, Schwülper 2006. ISBN 978-3-938693-05-6 .

- Gerd Spittler: Droughts, war and hunger crises among the Kel Ewey (1900–1985). Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1989. ISBN 978-3-515-04965-8 .

- Gerd Spittler: Acting in a hunger crisis. Tuareg nomads and the great drought of 1984. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1989. ISBN 978-3-531-11920-5 .

- Désirée von Trotha: The lizard's grandchildren. Images of life from the land of the Tuareg. Frederking & Thaler, Munich 1998; extended new edition, Cindigobook, Munich and Berlin 2013. ISBN 978-3-944251-02-8 .

Fiction

- Ibrahim al-Koni : The magicians. The Tuareg epic. Lenos Verlag, Basel 2001. ISBN 3-85787-670-0 .

- Ibrahim al-Koni: The Stone Mistress: Supplementary Episodes to the Tuareg Epic. Translated from the Arabic by Hartmut Fähndrich , Lenos Verlag, Basel 2004. ISBN 3-85787-354-X .

- Federica de Cesco : Hinani - daughter of the desert. 2008. ISBN 3-401-50048-1 (youth novel).

- Federica de Cesco: Samira - Queen of the red tents. Volume 1 of the Samira trilogy. Arena Verlag, Würzburg 2006. ISBN 3-401-05363-9 (youth novel).

- Federica de Cesco: Samira - guardian of the blue mountains . Volume 2 of the Samira trilogy. Arena Verlag, Würzburg 2006. ISBN 3-401-05364-7 (youth novel).

- Federica de Cesco: Samira - heiress of the Ihagarren. Volume 3 of the Samira Trilogy. Arena Verlag, Würzburg 2006. ISBN 3-401-05875-4 (youth novel).

- Federica de Cesco: desert moon. Marion von Schröder, Munich 2000. ISBN 3-547-71765-5 . (Novel)

- Mano Dayak: Born with sand in the eyes. The autobiography of the leader of the Tuareg rebels. Unionsverlag, Zurich 1997. ISBN 978-3-293-00237-1 .

- Jane Johnson: The Soul of the Desert. Page & Turner, 2010. ISBN 3-442-20344-9 (novel).

- Heike Miethe-Sommer: Tuareg poetry. Cargo Verlag, Schwülper 1994. ISBN 978-3-9805836-1-9 .

- Alberto Vázquez-Figueroa: Tuareg. Goldmann Verlag, Munich 1989. ISBN 3-442-09141-1 .

Web links

- Artifact - Student Journal of Art History and Art: Symbols of Mysticism - Leatherwork of the Tuareg

- Günter Heckenhahn: The Tuareg. Their desert, their festivals. Annotated photo gallery.

- Edmond Bernus: Dates, Dromedaries, and Drought: Diversification in Tuareg Pastoral Systems. In: JG Galaty and DL Johnson (Eds.): A Word of Pastoralism: Herding Systems in Comparative Perspective. Guilford Press, New York 1990. pp. 149-176. (PDF; 2.1 MB)

- Karen L. Barron: The Effects of Time and Place on the Nomads of Niger. Chicken Bones: A Journal for Literary & Artistic African-American Themes

- Wolfgang Günter Lerch: Once the lords of the desert Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , September 8, 2011

- Markus M. Haefliger: Tuaregs as unwilling helpers of Ghadhafi. Former allies in Mali and Niger are turning away from the former Libyan rulers. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . September 27, 2011, accessed on September 27, 2011 (background report on the relationship of the Tuareg to Muammar al-Gaddafi in the light of the civil war in Libya 2011 ).

Individual evidence

- ^ John A. Shoup: Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East. An Encyclopedia Ethnic Groups of the World Ethnicity in Global Focus. ABC-CLIO, 2011 ISBN 978-1-59884-362-0 , p. 295.

- ↑ Prasse 1999: 380

- ^ Chaker, Claudot-Hawad, Gast 1984: 31

- ↑ Kohl 2007: 47

- ↑ Thomas Krings, p. 33 (see lit.)

- ↑ Thomas Krings, p. 33 (see lit.)

- ↑ IRIN News: NIGER: New Touareg rebel group speaks out (English)

- ↑ Scott Stewart: Mali Besieged by Fighters Fleeing Libya. In: Stratfor . February 2, 2012, accessed April 6, 2012 .

- ^ Tuareg proclaim their own state in northern Mali. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . April 6, 2012, accessed April 6, 2012 .

- ^ Maggie Fick: Tea with the Tuareg. International Herald Tribune, December 12, 2007

- ↑ Stühler 1978, Keenan 1977, Pandolfi 1998, Kohl 2007 a. a.

- ^ Henrietta Butler: The Tuareg or Kel Tamasheq . Unicorn Press 2015, ISBN 978-1-906509-30-9

- ↑ ASSHAK, TALES FROM THE SAHARA Zwitserland / Duitsland / Nederland, 2004 - Ulrike Koch A film by Ulrike Koch, press booklet, p. 11.

- ↑ Claudot-Hawad, 2000; Kohl, 2007

- ↑ Kohl 2008, Susan J. Rasmussen 2006

- ^ Claudot-Hawad 1993: 33