Small fort Benia Guedah Ceder

| Small fort Benia Guedah Ceder | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Guedah Ceder Castle, Henschir Guedah Ceder Castle, Henchir-Guedah-Ceder Castle |

| limes |

Limes Tripolitanus (back line) |

| Dating (occupancy) | a) late 3rd century b) Byzantine ? |

| Type | Small fort |

| unit | partially mounted, unknown unit |

| size | 60 m × 40 m (= 0.24 ha) |

| Construction | stone |

| State of preservation | very well-preserved complex with clearly visible structural structures |

| place | Benia Guedah Ceder / Guedah Ceder |

| Geographical location | 33 ° 39 ′ 18.6 " N , 9 ° 36 ′ 57.8" E |

| height | 150 m |

| Previous | Small fort Henchir Krannfir (southwest) |

| Backwards |

Tebaga-Clausura (north-north) Small fort Henchir el-Hadjar (north-east) |

The small fort Benia Guedah Ceder , which is also called Fort Henschir Guedah Ceder in historical German descriptions , is a late Roman military camp whose crew was responsible for rearward security and surveillance tasks on the Limes Tripolitanus in the Province of Tripolitania . The border fortifications formed a deep system of forts and military posts. The small garrison is located on the southern edge of the Tebaga strait in southern Tunisia , Gabès governorate .

location

To the south-east of the complex, which was built on a fertile plain in the middle of the semi-desert, rises the Matma Mountains. This massif forms the northern end of the Dahar mountain range . The unit barracked in the small fort was responsible for monitoring the Tebaga-Clausura . This barricade, equipped with a rampart, moat and watchtowers, was drawn by the Romans over 17 kilometers across the valley of Tebaga. The southern beginning of this barrier was at the Djebel Melab, at the foot of the Matmá Mountains, its northern end on the ridge of the opposite sickle-shaped mountain range of the Djebel Tebaga . The only passage flanked by two towers was about 1.10 kilometers north of Benia Guedah Ceder on a small hill. There was visual contact between the two systems.

The fortification of Benia Guedah Ceder is located on the north-western edge of the Djebel Dahar , whose northern foothills also include the Matma mountains. The highlands of Dahar, which open in the shape of a crescent to the north, with their elevations extend to Libya . In this mountainous region, the Romans built a staggered rear border fort chain. The south-eastern end point of the mountain range is in the mountains of Nafusa with the Thenadassa castle at the rear .

Research history

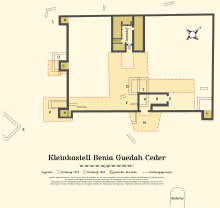

The rectangular, 60 × 40 meter (= 0.24 hectare) small fort was mentioned very early by French researchers. After the French officer Raymond Donau (1862–1930) had planned a first excavation in 1902 and was then able to publish it, he was given the opportunity to continue the investigations in 1904 with the help of a grant from the Tunisian Antiquities Administration. The building, which was erected in a region that is still remote to this day, has been preserved in a remarkably good condition since ancient times despite heavy stone theft.

Building history

The builders built the complex from ashlar masonry of a remarkably high quality. In three corners - in the south, east and west - rectangular towers were erected that protruded far from the wall. A single, structurally identical intermediate tower was built in the middle, on the south-western narrow side. The fort only had a narrow entrance on the southeast side, which was slightly shifted from the center. Inside the fort, this entrance was designed similar to a clavicle gate. In this way, attackers who had overcome the outer gate could be kept in check in a small space that bent to the northeast. Only after overcoming the gate located there, enemies could storm the interior of the fort. During the excavations at the beginning of the 20th century, it was found that the walls were between 0.60 and 0.80 meters thick. As a result of the stone robbery, the rising masonry remained between one and two meters high. It appears that the masonry on top of this ashlar wall base was narrower, with Donau and other researchers interpreting the apparent structural break as a Byzantine renewal.

The rectangular main building of the small fort was discovered - also shifted a little from the center - on the western longitudinal wall of the surrounding wall. Its back formed a unit with this enclosure. The only two meter wide entrance was dug on the opposite side. The actual entrance to the building, which is only 0.85 meters wide, was reached via a short corridor. It was arched and had to be entered via two steps. The keystone of the entrance vault is less than two meters from the ancient walking horizon. The whole building gives the impression of a small fortress. An atrium adjoins the entrance. Immediately on the left, a 1.10 meter wide entrance leads out of the atrium into a locked corridor that may have once served as a stairwell. This building, too, was built from ashlar masonry, which was measured up to three meters high when it was found. One room in this building identified the Danube as a stable, although the water troughs had still been preserved. The rest of the interior development was much more transitory and consisted of small, almost completely broken stone masonry.

During its excavations, Danube still registered traces of barracks and storage rooms. One of the remains of the soldiers in the interior of the fort was a stone block discovered during the excavations on which a phallus was sketched.

- Main building, construction status 2014

Dating

The construction of the complex can be assigned to the 4th century AD, but the lack of epigraphic references , among other things, makes a more precise chronological classification difficult. The pottery from the small fort dates back to the late 3rd century. As the oil lamp from the late second to early third century found under the foundations of the gate of the Tebaga-Clausura in 1904 from Donau showed, this passage could have been built in the late 2nd century AD. It is therefore possible to assign the founding of Benia Guedah Ceder to this period. Nevertheless, the archaeologist Pol Trousset dated the barrage in the 1970s to the middle of the 4th century, which could not be confirmed by sparse ceramic fragments from the 3rd century, which were picked up there in 1982. In 1902, Danube was only able to document a small, poorly preserved bronze coin from the small fort as a numismatic document. On the lapel was an emperor in field dress, who was leaning on a spear with his left hand and holding the globe in his right hand. The surviving inscription could be deciphered as "SPES REIPVBLICE", which is reminiscent of a coin from the reign of Emperor Constantius II (337–361).

literature

- David J. Mattingly : Tripolitania. Taylor & Francis, 2005, ISBN 0-203-48101-1 , p. 316, Fig. 10: 2.

- Pol Trousset: Recherches sur le limes Tripolitanus, du Chott el-Djerid à la frontière tuniso-libyenne. (Etudes d'Antiquites africaines). Éditions du Center national de la recherche scientifique, Paris 1974, ISBN 2-222-01589-8 , p. 68. Fig. P. 134.

- René Cagnat : La frontière militaire de la Tripolitaine X l'époque romaine . In: Mémoires de l'Institut national de France. Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres , Volume 39, Paris 1914, pp. 77-109; here: pp. 92–94.

- René Cagnat: L'armée romaine d'Afrique et l'occupation militaire de l'Afrique sous les empereurs . Imprimerie nationale, Paris 1912; Pp. 542-546.

- Adolf Schulten : Archaeological news from North Africa . In: Archäologischer Anzeiger. Supplement to the yearbook of the Archaeological Institute. (1904), pp. 117-139; here: p. 132.

- Raymond Donau : Le Castellum de Benia-Guedah-Ceder. In: Bulletin archéologique du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques 1904, pp. 467–477.

- Raymond Donau in: Jules Toutain : Notes ed documents sur les voies stratégiques et sur l'occupation militaire du Sud-Tunisien à l'époque romaine . In: Bulletin archéologique du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques , 1903, pp. 272–409; here: pp. 314–322.

Remarks

- ^ Archaeological finds in 1903 . In: Yearbook of the Imperial German Archaeological Institute , 19, 1904, p. 132.

- ↑ Michael Mackensen : forts and military posts of the late 2nd and 3rd centuries on the "Limes Tripolitanus" . In: Der Limes 2 (2010), pp. 20–24; here: p. 22.

- ^ Pol Trousset: Recherches sur le limes Tripolitanus, du Chott el-Djerid à la frontière tuniso-libyenne. (Etudes d'Antiquites africaines). Éditions du Center national de la recherche scientifique, Paris 1974, ISBN 2-222-01589-8 . P. 68.

- ↑ Tebaga-Clausura, Southeast end point at 33 ° 39 '23.59 " N , 9 ° 38' 46.12" O

- ^ Tebaga-Clausura, north-western end point at 33 ° 45 '10.7 " N , 9 ° 32' 11.01" E

- ↑ Tebaga-Clausura, gate at 33 ° 39 ′ 51.59 ″ N , 9 ° 37 ′ 19.56 ″ E

- ^ Pol Trousset: Recherches sur le limes Tripolitanus, du Chott el-Djerid à la frontière tuniso-libyenne. (Etudes d'Antiquites africaines). Éditions du Center national de la recherche scientifique, Paris 1974, ISBN 2-222-01589-8 . P. 134.

- ^ Raymond Donau: Le Castellum de Benia-Guedah-Ceder. In: Bulletin archéologique du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques 1904, pp. 467–477; here: p. 467.

- ^ Raymond Donau in: Jules Toutain: Notes ed documents sur les voies stratégiques et sur l'occupation militaire du Sud-Tunisien à l'époque romaine . In: Bulletin archéologique du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques , 1903, pp. 272–409; here: p. 321.

- ^ A b Raymond Donau in: Jules Toutain: Notes ed documents sur les voies stratégiques et sur l'occupation militaire du Sud-Tunisien à l'époque romaine . In: Bulletin archéologique du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques , 1903, pp. 272–409; here: p. 322.

- ^ David J. Mattingly: Tripolitania. Taylor & Francis, 2005, ISBN 0-203-48101-1 , p. 316, Fig. 10: 2.

- ^ David J. Mattingly: Tripolitania. University of Michigan Press, 1994, ISBN 0-472-10658-9 , p. 109.

- ^ David J. Mattingly: Tripolitania. Taylor & Francis, 2005, ISBN 0-203-48101-1 , p. 186; Fig. 5:17.