Benvenuto Cellini

Benvenuto Cellini (born November 3, 1500 in Florence ; † February 13, 1571 there ) was an Italian goldsmith and sculptor and a famous representative of Mannerism .

Benvenuto Cellini is considered one of the great sculptors of post-antiquity and a typical “uomo universale” of the Italian Renaissance . After his work had been almost forgotten for several hundred years, it was rediscovered at the beginning of the 19th century. On the threshold of the High Renaissance to Mannerism he worked as a sculptor, goldsmith, medalist, but also as a writer and musician.

Life

youth

Benvenuto Cellini was born on November 3, 1500 in Florence as the son of the builder and musician Giovanni Cellini and his wife Maria Elisabetta di Stefano Granacci in the 21st year of their marriage.

His father was a defensive architect for the Medici. In addition, he worked in arts and crafts areas and also made musical instruments. According to his will, Benvenuto should become a musician; However, at the age of 14, he decided to go into goldsmithing.

It was only with difficulty that Benvenuto managed to get his father to teach him to Michelangelo da Viviano, the father of his future arch-rival Baccio Bandinelli . However, when his father took him back soon afterwards, he ran away and went to Antonio di Sandro's workshop, where he made rapid progress. In 1516 he was banished from Florence for six months because of a brawl that he spent with the master Francesco Castoro in Siena . However, at the behest of Giulio de 'Medici , later Pope Clement VII, he was allowed to return. But it soon drove him back abroad. In Bologna he worked for a short time with Master Ercole, then for the miniature painter Scipio Cavaletti. Then he was back in Florence, which he soon left because of an argument with his brother to wander haphazardly via Lucca to Pisa , where he worked for a year under the master Ullivieri della Chiostra in beautiful and important things in gold and silver , before returning to Florence.

First stay in Rome

The music-making, which he had continued to do for the sake of his father, was now completely repugnant to him; There was a dispute with his father, as a result of which he left Florence again and went to Rome to the workshop of Firenzuola di Lombardia. However, at the request of his father, he returned after two years and also resumed making music. In the meantime, disputes with colleagues increasingly turned into fights, as a result of which Cellini - disguised as a monk - had to flee Florence.

He went back to Rome (around November 1523), where his patron Giulio de 'Medici was enthroned as Pope Clement VII.

In the workshop of Giovanpiero della Tacca from Milan , Cellini began a “large kettle” that the painter Gioanfrancesco Penni had designed for the Bishop of Salamanca. The swift execution of the commission was hindered after Cellini, moved by his father, who appeared to him pleadingly and threateningly in a dream, had entered the papal service as a musician. Annoyed by the delay in delivery, the bishop refused to pay according to the contract after receiving the work. After Cellini had managed to regain possession of the work, he defended the re-publication by force of arms against the bishop's servants. This coup made Cellini known in large circles in Roman society. The incoming orders made it possible for him to open his first own workshop. In addition to the goldsmith's work, he began to work as a seal engraver.

It was during this time that Cellini met his highly esteemed Porzia Chigi, to whom he owed a number of commissions and which encouraged him to open his own workshop. In the house of Chigi (today Villa Farnesina ) he studied the works of Raphael there , which should not have remained without influence on his further work.

Cellini, like many Romans, avoided the plague that broke out in Rome in 1525 by staying in the country. He bought the antique medals , gems and gemstones relatively often found by the farmers working in the fields for a small amount in order to sell them at a profit to art-loving cardinals back in Rome.

Sacco di Roma

During the siege of Rome in 1527, as a loyal supporter of the Medici, he also took up arms and took over the supervision of some of the guns at Castel Sant'Angelo . On behalf of the Pope, he destroyed a number of valuable works of art of goldsmithing, worth a total of 200 pounds of gold, without any scruples, in order not to let them fall into the hands of the besiegers. He embezzled part of the treasure. Joseph Victor von Scheffel mentioned Cellini's role in Sacco di Roma in Der Trompeter von Säkkingen . During the siege of Bad Säckingen by a heap of farmers, the secondary character, fresco painter Fludribus, says: “With a sharp look I / I recognized the danger, but how Cellini / From Castel Sant'Angelo once / France's connoisseur shot to death: / So - unfortunately worse Enemies - / cannon Fludribus here! "

After the end of the siege, he returned to Florence as Capitano, and soon after went on to Mantua , where he worked for a short time in the service of the Milanese Niccolo, the Duke's goldsmith . Four months later he was back in Florence, where the plague had just raged. He only found one brother and one younger sister alive. For the sake of these he stayed at home for a while and earned his money mainly by setting jewels.

On behalf of Girolamo Mazzeti he worked out a "gold medal to wear on the hat, whereupon a Hercules in a very sublime relief ripping open the lion's throat". This work won the applause of Michelangelo Buonarroti . Through this praise of the artist, who was already “deified” at the time, his need for recognition increased enormously and his desire for larger-scale works grew. Another medal from this period for Federico Ginori later came into the possession of Francis I of France and subsequently led to his appointment to the French court.

First murder

Cellini went back to Rome from Florence and worked there temporarily for the goldsmith Raffaelo del Moro. Thanks to the favorable order situation, he was soon able to open his own workshop again, in which five journeymen worked for him. His brother Francesco, who was in Rome as a soldier, was shot dead in a scuffle on the street during this time. Cellini's subsequent murder of his brother's murderer is punished by the Pope "with a grim sidelong glance".

After breaking into his workshop at night, in which a number of pieces of jewelry and dies were stolen, counterfeit coins struck with his stamp came into circulation. Cellini came under suspicion of counterfeiting, against which the Pope defended him. After the discovery of the perpetrators, the Pope saw his trust in him strengthened and gave him the lucrative position of a papal body satellite. This hierarchical rise led Cellini to a series of arrogance and quarrels until he was finally faced with a superior force of enemies.

When Cellini seriously injured one of his opponents by throwing a stone on the street, he had to flee to Naples and worked there for a short time in the workshop of the goldsmith Domenico Fontana, but soon returned secretly to Rome, where he waited for his victim to recover.

Pope Paul III

Pope Clement VII died in 1534. He was followed by Paul III. from Farnese . On the appropriate occasion Cellini killed Pompeo de 'Capianeis, the instigator of his persecution. Instead of being punished for this by the Pope, he received a charter from him. Secured by this, he first worked the stamps for the issue of new Scudi on the occasion of the election of Paul III. Meanwhile, the family of the murdered Pompeo, after finding no right, sought to reward like with like. Cellini escaped the hired murderers to Florence.

Another license from the Pope enabled him to return to Rome. There he was attacked one night and saved himself not least through a license. Then he became so life-threatening that he was expected to die. Although there were already sonnets written about his death, he miraculously recovered. Thereupon he sought complete healing in his sister's house in Florence.

Cellini claims to have committed three murders. The third happened at a postal worker in Siena. He was tried several times in his life. He was once sentenced to death. In addition to offenses for bodily harm, Cellini was also tried several times for theft and sexual practices that were regarded as abnormal.

First trip to France

In 1535 he traveled via Padua , Venice , the Bernina and Albula passes to Switzerland and from there to Lyon and on to Paris . However, the trip went without the hoped-for success. A meeting with King Franz I did not take place and so he traveled back over the Simplon Pass . After paying his respects to the Duke of Ferrara on the way and thanking Loreto for his recovery, he went on to Rome and reopened a workshop with twelve journeymen.

captivity

There his past caught up with him. He was arrested on the basis of a rumor launched by his enemies that he had stolen precious stones while melting down the papal treasure. He remained imprisoned in Castel Sant'Angelo for two years without charge. An attempt to escape resulted in even stricter detention. Attempts have been made to poison him. Cellini was only released after the intervention of the Cardinal of Ferrara, Ippolito d'Este ; he had the order to bring him the invitation to the French court of Franz I. Cellini set out for France for the second time on March 22 of the following year.

Second trip to France

In Fontainebleau he met King Francis I for the second time, who promised him major commissions. But Cellini soon became dissatisfied: The orders failed to materialize, and he found the prospect of payment to be inadequate. So he planned, as already considered during his imprisonment, to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He left abruptly one morning, but was caught and brought back. The breakaway attempt was successful, however, as the king immediately awarded him the commission for twelve life-size silver statues. He was given a small castle as a studio in the immediate vicinity of the Louvre , which he could only move into after repeated disputes with the residents there.

The work on the figures met with the lively interest of the king, who also surprisingly visited him in his workshop. During one of these visits, the king was commissioned to manufacture the salt barrel , the model of which Cellini had already made in Rome for Hippolyt d'Este. The protection of the king also led to a flood of orders for the workshop from outside. Numerous works were created in precious metals and in bronze. Here, too, Cellini made influential enemies in a very short time, first and foremost the king's mistress, Madame d'Étampes .

Return to Italy

In the summer of 1545 Cellini asked for leave, which was finally granted to him after initial refusals. He traveled to Italy. At the end of July he reached Florence and presented himself to Duke Cosimo , who asked him to enter his service. The sculpture of Perseus he had promised , with which Cellini hoped to compete with his great models Michelangelo and Donatello , appealed to him so much that he accepted the offer. Francis I accused him of ingratitude, demanded an exact account and waived his return.

In Florence the Duke gave him a house in 1545, which he lived in until the end of his life in 1571 and in whose garden Perseus was watered under adventurous conditions. The completion of Perseus took eight years due to recurring difficulties. In addition, there were still occasional goldsmithing works, which he and his assistants carried out mainly for the ducal court. From then on he saw himself more as a sculptor than a goldsmith.

Font of Perseus

After several successful casts on a bust of the duke and four smaller statues for the Perseus base, he cast the decapitated Medusa lying at Perseus' feet . After he had succeeded in this casting to his absolute satisfaction, Cellini finally took action and prepared the casting of Perseus, which, like the ancient bronzes, had to be done in one piece. The description of the company found a large place in the vita - how after the kick-off the roof beams caught fire, rain and storm penetrated, and finally the glowing stove burst. After two days, however, it became apparent that the casting had succeeded exceptionally well, except for a small spot on the right foot. He brought this news to the Duke at the same time as he asked for leave. This was granted to him and Cellini traveled to Rome.

His efforts there were for a position under Pope Julius III. which he was denied. Back in Florence, he worked on building some fortress gates before resuming work on the base of Perseus. In 1554 the Perseus was placed in the Loggia dei Lanzi , where it is still today. After Cellini did not want to leave the four figures for the Perseus pedestal to the Duchess , who coveted them for her private collection, he had also largely gambled away his credit in the duke's family, so that no more major orders were to be expected from there. To make matters worse, the parties could not agree on the price of the monumental sculpture. Cellini asked for 10,000 Scudi, while the Duke only paid 3,500 Scudi.

The Perseus was Cellini's greatest work. In the year of the unveiling, Cellini was solemnly accepted into the Florentine nobility, despite the fact that at that time he had sunk deeply in the duke's reputation, although without falling out of favor.

Last years

The eternal quarrels and the ultimately unfulfilled desire for recognition showed ever clearer traces on Cellini. So he decided to change to the clergy and also took the tonsure in 1558 . But that didn't change much about his quarreling. The last few years have been gloomy for him. He had misfortune with those who administered his money and became involved in lawsuits; since he did not work or worked very little, there was no income.

He was released from his vows in 1560 and married his housekeeper Piera di Salvadore Parigi in 1563, with whom he already had an illegitimate son, who had died in 1559. The sixty-three-year-old's marriage resulted in three children, two daughters and one son, who survived him, while his numerous illegitimate children mostly died in early youth.

Regardless of this, Cellini was repeatedly confronted with accusations of homosexuality , especially on the part of Baccio Bandinelli. The history of art also often connects the formal language of his sculptures with homoeroticism . He has been charged with sodomy four times .

- At the age of 23 he was charged with having sodomism with a boy named Domenico di ser Giuliano da Ripa. The verdict was mild, probably due to his young age.

- He successfully got through an indictment in Paris.

- In 1548 he was accused by a certain Margherita of being close to her son Vincenzo. But this is probably a causally different dispute, which Cellini escaped by fleeing.

- In 1556 he was accused of sodomy by the mother of his pupil Fernando di Giovanni di Montepulciano, who had been a model for Perseus; therefore Cellini was sentenced to fifty scudi in gold and four years in prison. The sentence was commuted to house arrest at the intercession of the Medici.

After the last few years of great financial difficulties, from which numerous letters of petition have been received, Cellini died on February 13, 1571 in Florence of pleurisy from which he had suffered for a long time.

Afterlife

- With the grandson Jacopo Maccanti, the descendants of Cellini died out in 1662. His estate came by will to the Buonomini di San Martino , from whose archive the documents relating to Cellini were later transferred to the Bibliotheca Palatina in Florence, where they are still preserved.

- Hector Berlioz composed the opera Benvenuto Cellini about Cellini's life in 1838 based on a libretto by Léon de Wailly and Henri-Auguste Barbier .

- Franz Lachner composed his opera Benvenuto Cellini in 1849 on the same libretto.

- Alexandre Dumas wrote a drama Benvenuto Cellini and a novel Ascanio based on Cellini's vita.

- Paul Meurice wrote the drama Ascanio in 1852 , based on Dumas' novel.

- Camille Saint-Saëns composed the opera Ascanio in 1890 based on a libretto by Louis Gallet based on Meurice's drama and Dumas' novel.

- Gregory La Cava's 1934 feature film The Affairs of Cellini with Fredric March in the title role deals with Cellini's vita.

- In 1945 Kurt Weill composed the operetta The Firebrand of Florence with lyricist Ira Gershwin and book author Edwin Justus Meyer based on legends from Cellini's biography.

Works

One of his best-known works is the Saliera , which he made for the French King Francis I from 1540 to 1543 in Paris . The salt barrel was stolen from the Vienna Art History Museum in 2003 , but was recovered by the Austrian police in January 2006.

Cellini's best-known sculptural work is the bronze statue of Perseus with the head of Medusa from 1554. The larger than life statue was placed in the Florentine Loggia dei Lanzi. Cellini also designed the marble base with four bronze statuettes of Jupiter , Mercury , Minerva and Perseus' mother Danaë . Later, a bronze relief by Cellini was added to the base of the base , depicting the liberation of Andromeda , which is now in the Bargello and was replaced by a replica on the base. From December 1996 to June 2000 the statue was extensively restored in the Uffizi workshops .

Another important sculpture can be found today in the Church of the Escorial near Madrid. It is a life-size marble crucifix that Cellini created for his own burial place in the last few years. Via the Medici, the work came to the church of San Lorenzo del Escorial. Since it shows Christ naked, it was shamefully covered with a linen cloth and given a crown of thorns.

A third surviving work is larger than life bronze bust, Cosimo represents. Cellini created these in competition with the Florentine sculptor Baccio Bandinelli . It was finished in 1548, stood in the Palazzo Vecchio (or Palazzo della Signoria ) until 1557 , was then "banished" to Cosmopoli on Elba and only became part of the Florentine sculpture gallery, the Bargello , in the 18th century .

The salt barrel, the Perseus , the bust of Cosimo and the crucifix are important examples of Florentine mannerism in sculpture . This manifests itself in their lavish furnishings, the complex iconography and the inclusion of the latest trends in sculpture, such as the demand for multiple perspectives and the “ figura serpentinata ”.

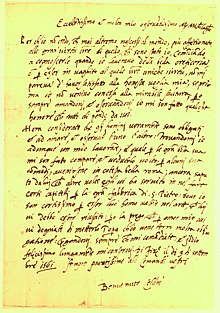

Cellini's writings

Cellini began writing his autobiography around 1557 and continued this work for about a decade. Then he destroyed the part of his writing that concerned the time in the service of Duke Cosimo , for fear of the possible wrath of the Duke, who later became the first Grand Duke of Tuscany, and from then on he did not carry on with his project. The autobiography ends quite abruptly in November 1566. It was not until 1728 that a print edition was made after a handwritten copy was presented by the Florentine Antonio Cocchi. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published the book in German in 1798 under the title Life of Benvenuto Cellini . Its edition is a very free, inaccurate translation with omissions. The emphasis with him is on the literary interest in the figure of the author. The book then found its way into his collected works. Another edition followed in Florence in 1830, this time based on the recovered original manuscript. One of the current translations of the original manuscript is by Jacques Laager.

Cellini also wrote two treatises on the goldsmith's art and the sculpture Trattati dell 'Oreficeria e della Scultura di Benvenuto Cellini , which were published during his lifetime - in 1568. In the last years of his life he also wrote a few short treatises on architecture.

Fonts

- Benvenuto Cellini: My life. The autobiography of a Renaissance artist . Translated from Italian and with an afterword by Jacques Laager. Manesse-Verlag, Zurich 2000, ISBN 3-7175-1946-8 .

- Treatises on goldsmithing and sculpture = I trattati dell'oreficeria e della scultura / Benvenuto Cellini. On the basis of the translation by Ruth and Max Fröhlich as a workshop book, annotated and edited. by Erhard Brepohl / 2005, ISBN 3-412-24705-7 .

- Benvenuto Cellini: Art and Art Theory in the 16th Century / ed. by Alessandro Nova and Anna Schreurs / Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2003, ISBN 3-412-11002-7 .

- Life of Benvenuto Cellini, Florentine goldsmith and sculptor / written by himself. Translated and with an appendix ed. by Johann Wolfgang Goethe. With an afterward by Harald Keller / 1996, ISBN 3-458-32225-6 .

- Life of Benvenuto Cellini, written by himself. Translated from Italian into German by Heinrich Conrad, with thirty-two pictures by Michael Mathias Prechtl. Frankfurt am Main and Vienna: Gutenberg Book Guild / 1994, ISBN 3-7632-4000-4 .

literature

- Susanna Barbaglia and Charles Avery : L'opera completa del Cellini. Rizzoli, Milan 1981.

- John Pope-Hennessy: Cellini. Abbeville Press, New York 1985.

- Andreas Prater: Cellini's salt barrel for Franz I. A tabletop device as a symbol of rule. Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-515-05245-3 .

- Alessandro Nova and Anna Schreurs (eds.): Benvenuto Cellini. Art and Art Theory in the 16th Century. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-412-11002-7 .

Web links

- Benvenuto Cellini at Google Arts & Culture

- Literature by and about Benvenuto Cellini in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Benvenuto Cellini in the German Digital Library

- Horst Bredekamp: The art of the perfect crime. Article in the period 50/2000

- Illustration of the Cosimo bust www.scultura-italiana.com

- Illustration of the crucifix www.scultura-italiana.com

- Works by Benvenuto Cellini in the Gutenberg-DE project

supporting documents

- ↑ Joseph Victor von Scheffel: The trumpeter of Säkkingen . 200th edition. Adolf Bonz & Comp., Stuttgart 1892, p. 172 .

- ↑ Antono Cocchi (ed.): Vita Di Benvenuto Cellini Orefice E Scultore Fiorentino, Da Lui Medesimo Scritta, Nella quale molte curiose particolarità si toccano appartenenti alle Arti ed all 'Istoria del suo tempo, tratta da un'ottimo manoscritto. Colonia 1728

- ↑ Benvenuto Cellini: A History of the XVI. Century after the Italian by JW von Göthe. Braunschweig: At I. Bauer, 1798.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Cellini, Benvenuto |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian sculptor and goldsmith, representative of Mannerism |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 3, 1500 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Florence |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 13, 1571 |

| Place of death | Florence |