Mesopotamian art

The Mesopotamian art representing the cultural flowering of the ancient Near East , one of the first civilizations from around 3000 BC. Chr.

Mesopotamia , the Mesopotamia between the Euphrates and Tigris , includes areas of present-day Iraq , southwest Iran , Syria and South East Anatolia . This region has been inhabited by people since the Neolithic , who lived here around 3000 BC. First reached the rank of high culture. This high culture is mainly based on the Sumerian people . In the course of the third millennium, a Semitic group emerged with the Akkadians , who finally prevailed and their descendants (especially the Assyrians) remains the dominant group in the ancient Orient into the first millennium. In the middle of the second millennium, the Kassites appeared, another ethnic group that remained dominant for several centuries, especially in southern Mesopotamia. Only in the late period of the Ancient Orient did the Persians gain the upper hand.

These and other peoples made their contribution to the art of the country. Nevertheless, there are certain elements that have remained constant over the millennia or at least can be regarded as typically Mesopotamian. In architecture it is the use of adobe bricks and the construction of temple towers, the ziggurats . The sculpture was only of greater importance in the third millennium BC. In the flat above all is Glyptik remarkable. Bas-reliefs enjoyed great popularity in almost all epochs, but experienced a high point among the Assyrians, who richly decorated their palaces with them. Apart from chance discoveries, little has survived of the painting, which was once important.

For a better overview, the cultures and kingdoms are classified geographically below, whereby the location refers to the core area and not to the overall distribution.

South Mesopotamia

Early history

The early history of Mesopotamia corresponds roughly to the period from 3500 to 2900 BC. These are the periods called Uruk VI-IV and Jemdet-Nasr times , during which monumental temples were built, especially in Uruk . This period is sometimes called the “early Sumerian period”, as the subsequent epoch was primarily shaped by the Sumerian culture. However, since it is unclear when and how the Sumerian population came to Mesopotamia, this designation remains anachronistic .

architecture

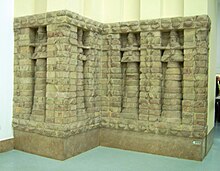

The most impressive monuments of early history are the temple complexes of Uruk . Monumental buildings were erected here. They usually have a facade with niches in common. The interior had a T-shaped courtyard.

The so-called limestone temple was 70 × 30 m in size and built from limestone blocks. This is remarkable in itself, since otherwise almost all Mesopotamian buildings were made of adobe bricks. However, it is uncertain whether the entire structure or just its foundations were made of stone. The building was strictly symmetrical. Inside there was a large courtyard that took up almost the entire length and was surrounded by various rooms. In the south, the courtyard widened so that the interior appears T-shaped in plan. The building was provided with a niche facade. The function as a temple is not guaranteed, but seems likely due to the mass and shape of the architecture, which corresponds to other temples in the complex. The Inanna Temple in Uruk was decorated with columns and had a monumental courtyard. The walls were decorated with mosaics that made geometric patterns from small pencils.

Other temples of this time could be excavated at Eridu , Tell Uqair and Tell Brak . These examples have an inner courtyard without the extension. Many of these temples stand on a podium, so they were elevated above the rest of the city. Extensive remains of wall paintings were found in the temple of Tell Uqair.

Round picture

There are only a few round pictures from this phase. Most of them are undemanding clay idols, few are made of stone. These are usually rather rough. A statue from Uruk , now in the Louvre, shows a naked man. He wears a beaded headband and a full beard. The legs are only worked in summary form. The interpretation of the work causes difficulties. As a rule, prisoners are depicted naked, while hair and beards indicate a prince. Is there a captured prince shown here?

In a layer of the Jemet Nasr period in Uruk, an almost life-size woman's head made of marble was also found. It is part of a composite statue. Instead of the eyebrows and eyes, there are grooves and hollows that once contained deposits. The parting also has a groove, which was certainly used to attach a hairstyle. This face is considered to be the earliest sculptural work of art of the first order.

Flat screen

Some alabaster vessels come from this era , the outside of which is decorated with flat reliefs and gives a good impression of the artistic level of this period. A tall vase from Uruk shows scenes in three registers. In the top one are portrayed who bring various gifts to a person, perhaps a deity. In the middle register, only victims and animals and plants appear at the bottom. The interpretation of the representations is uncertain. Is a real event or a mythological occurrence reproduced here? The figures are full, somewhat stocky, but well proportioned.

Numerous representations on cylinder seals have also been preserved in the flat screen . A wide repertoire of images is documented. There are ritual depictions, sacrificial, hunting and war scenes. Representations of wild animals and hybrid creatures , which are often arranged in a heraldic way, are particularly typical of this period .

Early dynasty

This is the period from circa 2900 to 2350 BC. The names of the first rulers have been passed down, which are also documented on contemporary monuments. The city of Kiš played the leading role in politics . New approaches in art and construction technology can be observed in many areas, which justify treating this as a separate epoch. The image of man is primarily characterized by the depiction of large eyes and large noses. The figures often appear expressionistic , remote from nature and are highly stylized.

architecture

New techniques are finding their way into architecture. Plano-convex bricks now appear, which are curved on one side. For important buildings, deep pits are dug, which are often filled with pure sand. The first known monumental palace building in Mesopotamia dates from this period.

The best-researched temple of this period is the oval temple in Hafaǧi . The actual temple building stands on a platform that can be reached by stairs. In front of the platform was a large courtyard, around which various rooms were grouped. The whole complex was surrounded by an oval wall. A comparable, poorly preserved temple was excavated in el-Obed . The temple of Sarra in Tell Agreb is designed quite differently. It is an almost square building with strong outer walls and various courtyards. Although these temples look different at first, they have the temple wall in common, which shields them from the outside world. In the temple area there were priestly apartments and business units.

The first palace excavated so far comes from Kiš. The building consists of two parts that were built one after the other. There was a monumental entrance. In the center of the northern and older building there was a courtyard, which was probably the core of the complex. In the south there was a later extension with two large halls in the west. The plan is rectangular.

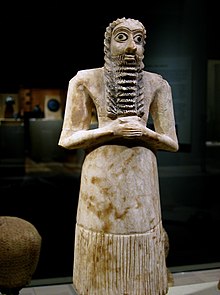

plastic

There are numerous sculptures from this period. They were mostly found in temples and probably represent prayers before deities. They usually wear a long beard and long skirt, which is provided with a shaggy hem at the lower end. The upper body is naked. Earlier examples often seem strongly stylized. The figures have oversized eyes, a large nose and the head is usually too small in relation to the body.

Some sculptures from Mari show comparable stylistic features, but in a weaker form. The trend towards a more naturalistic representation can be observed here.

Flat screen

A well-documented group of monuments are consecration tablets. They are usually divided into three registers and have a symposium scene as their main topic . A woman sits on one side and a man sits on the other. They both hold a drinking cup in their hand. There is a large mixing jug between the two and there are numerous servants, musicians and dancers. In the middle, the panels have a hole through which they were obviously attached to an object that has not been identified with certainty or to a temple wall. The style of the figures shown is reminiscent of contemporary statues. The nose and eyes are oversized. Most of the figures appear bare-chested and wear a shaggy skirt.

In the glyptic there are comparable motifs, symposium scenes and heroes who conquer predators. A stylization of the figures can also be observed here. Often a network of figures is created, which is called a figure band. The figures are also strongly stylized in glyptics. The limbs and body are over-thin.

I dynasty of Ur

This period spanned the period from about 2550 to 2340 BC. And belongs to the early dynasty . The first dynasty of Ur is well documented by contemporary inscriptions.

architecture

Almost no new buildings have survived from this period. Old temples continued to be built, although hardly any innovations can be observed.

Round sculpture

In contrast to architecture, the sculpture of this period is very well documented. Above all, numerous so-called praying figures should be mentioned here. Usually a standing man is shown. He has a bare chest and wears a long villi skirt. The execution of these figures is initially relatively naturalistic. The figures lose more and more plasticity over time. In the better works, the face is usually well-proportioned. The hands are crossed over the chest. There are also numerous sculptures of women from this period. They usually stand out for their hairstyles and turbans. A prayer figure from Lagasch is completely blocky.

Flat screen

The consecration tablets with a central perforation continued to enjoy great popularity. However, other issues now arise. Deities are represented to whom sacrifices are made. The figures usually appear squat, with oversized eyes and noses. The face is usually shown in profile.

An important work of art of this time is the victory stele of the Eannatum of Lagasch , which is also known as the vulture stele . It is the oldest example of the genus of historical steles. The monument, rounded off at the top, is only preserved in fragments. It was once 1.8 m high, 1.3 m wide and 11 cm thick and is decorated with relief on all four sides. It celebrated the victory over Ummah, from which a disputed area could be recaptured. The stele is only preserved in fragments. The main character is the god Ningirsu , who is portrayed as the victor. On the front he appears as a king and holds the enemy like fish in a net, while he hits them in the skull with a club. On the back you can find various episodes from the war in several registers; soldiers with lances in a phalanx appear in the upper register .

Similar motifs can be found in the glyptic as in the previous epoch. There are figure friezes and banquet scenes that are very popular. Here, too, it can be observed that the figures are becoming more robust and no longer as overstylized as they were during the Old Sumerian Empire.

Fragments of the vulture stele

Ur-III period

After the empire of the Akkadians around 2200 BC The Guti , of whom little is known , ruled for about 100 years . They were followed by the third dynasty of Ur , in which large parts of Mesopotamia were reunited under one rule.

architecture

The most important innovation of the time is the introduction of the ziggurat , the classic Mesopotamian temple shape. Earlier temple buildings were often built on a raised platform, now this has been raised to a tower, on the top of which the actual sanctuary stood. The best preserved ziggurat is that of the moon god Nanna in Ur. The core building is surrounded by a thick shell of bricks. The four corners are oriented towards the cardinal points. In the middle there was a staircase that certainly once led directly to the top platform, where the Holy of Holies stood.

Various palace buildings have been preserved. The palace of the Urnammu in Ur was probably its main residence. It is a square building with two large courtyards. The building is reminiscent of the palace of Naramsin in Tell Brak and one might assume that an Akkadian building was copied here or that Akkadian traditions were continued.

plastic

A number of important sculptures belong to the city prince Gudea von Lagasch from the transition period to the third dynasty of Ur . These pictorial works combine the technical perfection of Akkadian works with Sumerian style. The prince is shown sitting or standing. His figure usually looks stocky, with a head that is a little too big and a body that is too short, making it appear heavy and blocky. Arms and legs are close to the body. There is no effort to detach them from this one. The strong muscles and the face are finely crafted. Gudea wears a round cap and is clean-shaven. The statues are usually richly inscribed and name the achievements of the prince.

No statues of the rulers of the third dynasty of Ur have survived. Some statues from Mari dating around this time show a slightly different style. Images show standing men in long coats. The figures are usually better proportioned, but less technically mature, perhaps betraying a certain provinciality. They also look very blocky. Arms and legs are not worked freely.

Flat screen

There are some remains of royal stelae from this period. The most important monuments are the fragments of two large stelae of Gudea from Lagasch and one stele of Urnammu from Ur, which show great similarities in style. They were once over 3 m high and placed in temples. The rulers used these steles to celebrate their good deeds, such as construction work, the irrigation of the land and perhaps also campaigns, and they asked for a long life with these. The steles have a round top with a main scene in the round field, while narrative actions are shown in four registers below. They are in relief on all four sides. The style of the figures combines the technical perfection of the Akkadian works of art with a more Sumerian style. Although the figures are not as blocky as in the sculpture at the same time, they still appear stocky. The relief is usually finely cut and modeled very three-dimensionally, with the reproduction of numerous details, for example in the folds of the robes.

Seals have been preserved from Gudea and Urnammu. They show the introduction of a prayer by an advocate before a god. This is a theme that also plays a special role in relief. Overall, a strong Akkadian influence can be observed in the glyph.

Old Babylonian time

After the fall of the Empire of the Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur, Mesopotamia split into numerous smaller political entities. Only Hammurabi of Babylon founded a great empire again, but it did not last long. The art of this epoch is not well documented, above all the remains of the buildings of the capital Babylon are hidden under later meter-thick layers.

architecture

Few new temples are known. The temples in Babylon are buried meters deep beneath the later layers. In other places it becomes clear that many of the previous periods were followed up, especially the construction of ziggurats seems to have continued. The ziggurat in Ur has been renovated.

A well-excavated temple building from this period is the ziggurat of Tell al Rimah in Assyria . In front of the actual ziggurat stood a large temple building with a large courtyard in the middle. Here the holy of holies was obviously not on the temple tower, but was in the temple directly in front of it. The facade of the temple was richly structured with a niche facade.

In terms of secular buildings, the palace in Mari in particular dates from this era, even if this building was built over several generations. Here, too, we can observe old traditions and, above all, the models of the Akkadian period. The building is rectangular, about 200 × 125 m in size with a square central building and is dominated by two courtyards. Smaller and the palace rooms are grouped around these courtyards. The building was decorated with paintings.

plastic

From Susa the head comes a ruler, which is often the Hammurapi is assigned. It is made of diorite and shows a man with a long beard and a round headgear. The facial features are somewhat stylized, but here, too, a reference to Akkadian models can be felt. The partly gilded bronze picture of a kneeling prayer probably comes from Larsa . The free working out of the individual limbs is remarkable. There is nothing blocky about the figure, as can be found in the stone sculptures.

Flat screen

The main work of the flat screen of this period is undoubtedly the legal stele of Hammurabi , which was found in Susa . It is made of black basalt and is 2.25 m high. It shows a picture of the king, as it has been known since the Gudea period. The king is standing, has a round cap and a robe that leaves the right shoulder and arm free. A god is enthroned before the ruler.

The wall paintings in the palace of Mari may also belong to this period. In principle, they show the same stylistic features as the relief. The figures and the background are mainly kept in various shades of brown. The ruler appears with a round cap and a long robe, as do various deities.

Middle Babylonian Period (Kassite Period)

The Kassites came around 1500 BC. He came to power and was to dominate the south of Mesopotamia for the next 400 years . While they enjoyed little reputation in historiography, they introduced many trend-setting innovations in the arts.

architecture

The oldest known Kassite building is a small temple that Kara-indaš built in Uruk . The building is made of fired bricks. Larger-than-life figures of deities stand in the niche-decorated facade. The building itself is relatively small and consists of the Holy of Holies and a walkway. The four corners in particular are clearly structured by projections.

A new capital was built in Dur-Kurigalzu , some of which was excavated. The most important building is the ziggurat, which is one of the best preserved in Mesopotamia today.

plastic

The sculpture of the Kassite period is characterized by a remarkable naturalism. New materials are used. In the palace of Dur-Kurigalzu there were clay sculptures, not simple clay idols (which are documented in all periods), but fully plastic works of art. A man's head has a long beard and has been carefully worked through. The good preservation of the color is remarkable. The head of a cat is worked extremely close to nature with the suggestion of the fur and the free reproduction of the body shape.

Flat screen

In the flat screen you will find a number of innovations, but also traditional ones. A scratch drawing from Babylon shows a lion attacking a boar. The drawing surprises with the realistic representation of the fight.

The figures on the wall paintings in Palace H in Dur-Kurigalzu are vigorously modeled, but do not appear as compact as the Sumerian period. This indicates a style that anticipates Neo-Assyrian style elements.

A new group of monuments are boundary stones ( Kudurru ). They are steles on which the king, or sometimes a high official, publicly announces the granting of land to a specific person. The stones were apparently placed directly on the appropriate land. On the sides of these stones there are usually long inscriptions, on the front there is relief decoration with a multitude of symbols of gods.

Neo-Babylonian Period

With neo-Babylonian art, the creation of art over the period from about 1100 to 539 BC. In southern Mesopotamia. It stands in the Middle Babylonian or Kassite tradition, but develops parallel to Neo-Assyrian art and is at times influenced by it. A special period of this development occurs during the Chaldean dynasty (626-539 BC) after the fall of the Assyrian Empire. Most of the evidence of Neo-Babylonian art and architecture come from the capital, Babylon .

architecture

The buildings of Babylon are certainly the most impressive evidence of this epoch. The city was expanded in a generous style. It received a new city wall, the main gates of which were lavishly decorated with glazed bricks. In the center of the city a large palace was built with a series of courtyards and monumental halls. The most important temple in the city was the Marduktempel Esagila . The gigantic ziggurat stood in the Etemenanki .

Round picture

Monumental sculptures are not known from this period. The finds are limited to small sculptures, mostly terracotta figurines and small figures made of unfired clay with an apotropaic function. Special finds include depictions of the demon Pazuzu , which should also protect their owners.

Flat screen

A stele fragment of Šamaš-rēš-uşur , governors of Suhi and Mari , from the so-called Castle Museum in Babylon dates back to the Neo-Babylonian period . On this votive stele he is depicted between three deities, accompanied by astral symbols in the upper part of the stele. Furthermore, a kudurru of King Marduk-apla-iddina II is known. On this black marble monument he is depicted in the usual Babylonian ruler's costume. Characteristic is the long shirt, folded at the back and a cone-shaped cap with a long ribbon. In front of him stands a small depicted subject who, according to the inscription on the kudurru, is enfeoffed with lands. He only wears a diadem as a headdress , and his staff is also shorter than that of the king, in keeping with his rank. This scene is crowned by a number of astral symbols. A stone relief of Nabû-apla-iddina comes from Sippar , which shows an introductory scene of the king before the sun god Šamaš . Its inscription commemorates the restoration of the temple É.BABBAR around 870 BC. Another stele in relief shows the last ruler of the Chaldean dynasty Nabonid in front of the astral symbols moon (Sîn), winged sun (Šamaš) and Venus (Ištar). The standing, left-facing ruler wears an Assyrian shawl robe and the Babylonian king's cap. He wears bangles on his wrists as jewelry, and in his left hand he holds the staff of the Babylonian kings.

Wall painting and wall decorations

A splendid way of decorating walls with color is to decorate them with glazed bricks. In this way Nebuchadnezzar II adorned important buildings of his capital Babylon, which were of both representative and religious importance, the Ištar gate , the processional street and the throne room facade of the south castle . The Ištar gate was decorated with representations of bulls and serpent kites , mušḫuššu . The walls of the processional street, which were located north of the Ištar gate , were decorated on both sides with rows of striding lions. After Koldeweys estimate the number of lions was at least 60 at each side. The lower part of the throne room facade was also decorated with lions. Similar representations seem to have been on the gate towers of the central and east courtyard in the south castle.

Glyptic

The neo-Babylonian glyptic mainly deals with so-called adoration scenes . Seal pictures show worshipers in front of god symbols. The iconographic repertoire also includes winged scorpion people and other mythical creatures. The scorpion man (Akkadian girtablullû ) is a creature with a human head, claws of a bird and a scorpion tail. This figure appears for the first time on a cylinder seal in the Akkad period. But the representation of the hero with six curls fighting a lion also finds its place in neo-Babylonian art. This motif also appears in the art of the 3rd millennium BC. Chr. On. There are also seals with warlike content, such as riders on horseback or on a camel.

Northern Mesopotamia

Akkad time

The empire of Akkad flourished from around 2300 to 2100 BC. Large parts of Mesopotamia were now united under one ruler for a longer period of time. Numerous innovations can be seen in art. Something like imperial art emerges. Above all in the works of sculpture and the flat screen, the rulers present themselves in a new, mature style, which in its naturalistic representation of body shapes and technical perfection goes further than was previously documented in Mesopotamia.

architecture

Little is known about the buildings of this period. Above all, the capital Akkad has not yet been found, so that one cannot get any idea of the palaces and temples in this place. In Tell Brak a palatial building was excavated. Only the foundation walls have been preserved, showing that the building was around 100 × 100 m in size. The rooms were grouped around a courtyard. The building is clearly structured, has strong walls and suggests a well thought-out plan.

plastic

The Akkadian rulers seem to have decorated the temples or palaces of the empire with their sculptures. These are often made as a hard rock like diorite . All of these works are only preserved in fragments. But they show a clear step in the direction of naturalistic representation. A torso from Susa shows Maništušu standing. He wears a long skirt, the work is broken off in the abdominal area, but the robe shows a clear effort to depict folds. The fragment of a male statue from Assyria shows only the chest and the right arm of a figure. Here, too, the naturalistic reproduction of the arm and chest muscles can be observed. Probably the most important work of this time is a bronze head of a ruler found in Niniveh .

Flat screen

Some important victory stelae date from this period, which on the one hand tie in with the vulture stela of the previous epoch, but clearly show an Akkadian style. The fragments of a stele from Sargon von Akkad come from Susa. Here prisoners can be seen in various registers. A fragment whose assignment is uncertain shows prisoners in a network. It is important that it is not the god but the king who slays the enemy.

One of the most important works of the period is the stele of Naramsin , which celebrates the victory over the mountain people of the Lulubeans . The stele is 2 m high. The ruler is depicted as a conqueror climbing a mountain. His soldiers follow him. The figures are well proportioned and far removed from the stockiness of earlier human representations in the art of Mesopotamia. The relief is strongly modeled. The representation of the figures is characterized by a love for details.

During this time, the image of a Mesopotamian ruler becomes tangible for the first time, as it was to become almost canonical for the following epochs and perhaps indicates how much the image of the ruler of the Akkadians should be decisive in the next few centuries. The king is depicted as bearded, wearing a round cap and a long robe that leaves the right shoulder and arm free. The left arm is completely covered by the robe.

New motifs are emerging in glyptics. In the previous epochs, deities rarely appeared. Now you can find scenes from the Epic of Gilgamesh or the greeting of the sun god. It is controversial whether these images were specially designed for the seals or whether one is dealing with copies of lost monumental reliefs.

Ancient Assyrian Period

From the ancient Assyrian period (first half of the 2nd millennium BC) there are hardly any objects that could provide information about a special Assyrian style. An exception are cylinder seals and seal unwinds from Karum Kaneš (Kültepe). But here, too, a clear determination of Assyrian elements and themes is quite difficult, since the seals have many different influences. In the glyptic, both a formal and substantive relationship with the ancient Babylonian art of seals can be recognized. Examples of this are the adoration scene and iconographic motifs such as costume or various symbols. Differences to Babylonian seals can be recognized by the rough, heavy cut of the face, hair and clothes. There is, however, no connection to the more recent Central Assyrian glyptics. Based on inscriptions with the names of the rulers Erišum I , Šarru-kīn I , Naram-Sîn (Assur) and Šamši-Adad I , seals can be clearly dated to the ancient Assyrian period. Small terracottas (idols, single-axle wagons) have survived in large numbers, which were not used as children's toys, but fulfilled religious or at least magical functions.

An example of relief art from this period is the victory stele Šamši-Adads I from Mardin. Its obverse shows a triumphant ruler setting foot on a defeated enemy. Two prisoners are shown on the back. The inscription on the stele describes fighting in the East Tigris area. The monument is not specifically Assyrian, but fits stylistically and thematically into the Mesopotamian art of the time.

Neo-Assyrian time

Since the beginning of the first millennium BC, the Assyrians rose to become a great power. At its peak it was to rule large parts of the Near East. All arts experienced a remarkable boom.

architecture

The Assyrians founded new residential cities or built old cities into magnificent royal cities with monumental palaces and temples.

Dur Šarrukin is a foundation of Sargon II. The city is about 3 km² and surrounded by strong walls. In the north was the palace district. The palace was built on a 15 m high terrace, which dates back to 708 BC. Was completed. In this palace there were numerous representation and living rooms, temples and service wings. There was a ziggurat, presumably seven steps, about 42 m high. The palace was decorated with reliefs of Sargon II's military campaigns and gigantic gatekeeper statues. The gatekeepers were hybrid creatures, either human-headed bulls or winged bulls and lions.

Round picture

The round picture of this epoch is attested above all by pictures of rulers and in building sculptures. Together with the architectural features, the latter forms the “total work of art” of the typical Neo-Assyrian palace. The few examples of depictions of rulers using this technique, seated and still images, appear very static. The focus on the elaboration of surface structures and the low spatial depth show the proximity to the flat screen. As there, the kings are depicted in Assyrian shawls and with the typical hair and beard costume. Monumental representations of so-called Lamassu adorn many door jambs of Neo-Assyrian palaces. The presentation can be aptly described as a fusion of round and flat screens. The hybrid beings are only shown from two sides. Both views are independent of each other, as evidenced by the presence of three front legs. The almost fully three-dimensional representation of the head and the comparison with the otherwise very flat Neo-Assyrian reliefs speak against the designation as flat. In contrast to numerous flat screens, the underlying stone blocks have a static load-bearing function here. Contemporary written sources indicate that other depictions of animals were part of the architectural sculpture of Neo-Assyrian palaces. Sargon II had eight bronze lions mentioned in a building inscription, which are said to have served as pillars.

Flat screen

Large-format wall reliefs, such as those found in the ruler's palaces from the 9th to 7th centuries BC, are particularly typical of the Neo-Assyrian period. Were found. In addition, there are still different types of wall painting and reliefs on other image carriers, such as obelisks and throne bases. Wall reliefs, which were attached to so-called orthostats in numerous rooms of the palaces, enable the development of neo-Assyrian flat art to be followed due to their continuous presence. Remnants of paint on some pieces also show the original proximity of the reliefs to the wall painting, especially since in most cases it is an extremely flat relief. The motifs of the reliefs can be assigned to two different aspects of the Assyrian kingdom, namely the mythical-transcendent on the one hand and the secular-historical on the other. The reliefs of the first great ruler's palace of the Neo-Assyrian period, that of Aššur-naṣir-apli II. In Nimrud , show the ruler on the one hand in various ritual scenes, on the other hand they tell of the war and hunting successes of the king. The larger-than-life representations are partially provided with a wide cuneiform band halfway up. All figures stand on the same baseline, which gives the impression of a frog's eye view, which further increases the size effect. In the horizontal direction, the images get their structure from the natural boundaries of the individual orthostat plates, which were usually taken into account in the composition. Particularly in the narrative scenes, in which not only the space but also a chronological sequence is represented, a harmonious rhythm of the overall composition is striking.

The reliefs in the central palace of King Tiglat-Pileser III. this structure has been lost; the orthostat edges are not taken into account for the composition and there is a tendency towards naturalism: the previously neutral background is replaced by a detailed representation of the landscape, flora and fauna. The same applies to the palace of Sargon II in Dūr-Šarrukin. The developments observed continue in the 7th century AD with the reliefs in the south-west palace of Sennacherib in Nineveh. What is depicted is fixed in space and time both by the design of the background and by inscriptions, which in the case of the reliefs in the palace Aššur-naṣir-apli II. Could only be understood by combining the images with the annals.

Identical stylistic features as in stone relief can also be found in painting and bronze art. Bronze fittings for a gate come from Balawat and are richly decorated with scenes.

literature

- Jutta Börker-Klähn: Ancient Oriental steles and comparable rock reliefs , Baghdader Forschungen 4, Mainz 1982.

- Dominique Charpin, Dietz O. Edzard, Marten Stol: Mesopotamia - The ancient Babylonian period , Orbis biblicus et orientalis 160/4, Freiburg / Switzerland 2004.

- Dominique Collon: First Impressions. Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East , London 1987.

- Dominique Collon: Ancient Near Eastern Art , London 1995 ISBN 0-7141-1135-X

- Barthel Hrouda : New and Late Babylonian Art Period , in: Dietz-Otto Edzard u. a .: Real Lexicon of Assyriology and Near Eastern Archeology , Vol. 9, de Gruyter, Berlin 2001.

- Robert Koldewey : The again rising Babylon , 5th edition (ed. B. Hrouda), Beck Verlag, Munich 1990.

- Anton Moortgat : The Art of Ancient Mesopotamia, I. Sumer and Akkad , Cologne 1982 ISBN 3-7701-1393-4

- Anton Moortgat: The Art of Ancient Mesopotamia, II. Babylon and Assur , Cologne 1984.

- Astrid Nunn : The wall painting and the glazed wall decoration in the ancient Orient , manual of the oriental studies. Seventh Department, Art and Archeology, Volume 1, Section 2, B, Volume 6, Leiden; New York: EJ Brill, 1988

- Joseph Wiesner : The Art of the Ancient Orient , Frankfurt / M., Berlin 1963

- Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg: Art from Mesopotamia from the earliest times to Islam, exhibition of works of art from the Iraq Museum, Baghdad, October 4, 1964 to January 1965 (catalog), Hamburg 1964

Remarks

- ^ Moortgat: The Art of Ancient Mesopotamia , pp. 22–31

- ^ Moortgat: The Art of Ancient Mesopotamia , pp. 32–34

- ↑ (picture) The picture was stolen when the National Museum of Baghdad was looted, but could be found again

- ↑ Pictures of the Uruk vase ( Memento of the original from May 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Moortgat: The Art of Ancient Mesopotamia , pp. 34–36

- ^ Moortgat: The Art of Ancient Mesopotamia , p. 52, Fig. 19

- ↑ Pictures of the Ziggurat ( Memento of the original from November 25, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ picture (the object is lost today)

- ↑ picture (the object is lost today)

- ↑ Evelyn Klengel-Brandt, Die Terrakotten aus Babylon und Assur, in: Antike Welt 2/18, pp. 37-39

- ^ Moortgat: The Art of Ancient Mesopotamia , p. 98

- ^ Moortgat: The Art of Ancient Mesopotamia , p. 101

- ↑ Matthiae: "History of Art in the Ancient Orient 1000–330 BC" P. 60