Anton Graff

Anton Graff (born November 18, 1736 in Winterthur ( Switzerland ), † June 22, 1813 in Dresden ( Kingdom of Saxony )) was a Swiss painter of classicism . With his conception of images, Graff was one of the most important portrait painters of his era. He understood in his portraits, beyond the external resemblance, to grasp the character of a person precisely. At the end of the 18th century he became the real creator of bourgeois portraits of women and men in Germany and at the same time the preferred portrait painter of German-speaking poets and thinkers between the Enlightenment , Weimar Classics and early romanticism .

Anton Graff left for posterity an outstanding overview of the personalities of his time, in which there was hardly a great prince, statesman, general, scholar, poet, artist or merchant in Germany who did not allow himself to be portrayed by him. Graff's portraits thus represent historical documents. Anton Graff and his work received a lot of praise and recognition during his lifetime.

The Graf family

Anton Graff was the seventh of a total of nine children of the Reformed couple Hans Ulrich (* 1701) and Barbara Graf (f), born in 1727 . Boller from Zurich , born in the house at Untertorgasse 8 in Winterthur .

Two days after his birth, Graff was baptized on November 20, 1736 with the name Antoni , given to his older brother, who was born on November 8, 1733 and died the following year. Graff always called himself Anton, and those around him always called him that.

As is typical of the time, the spelling of the family name varied with a single or double "f". If Anton Graff designated his pictures, which was rarely the case, he usually did so with A (.) Graff pinx (.) And the corresponding year at the bottom right or on the back. In individual cases he added a location. In 1770 Johann Caspar Füessli's publication History of the Best Artists in Switzerland appeared together with their portraits, in the third part of which Füessli used the spelling with a simple "f" for Graff.

Childhood and education in Switzerland

Graff's family had gained citizenship in Winterthur in 1350 and had been divided into two branches since the late 17th century. In one branch the office of weighmaster was hereditary , in the other, from which Anton Graff sprang, the pewter caster was hereditary. Had it been up to his father, who was also a tin caster, Anton Graff would also have learned this profession. Graff was not a model student and was accordingly not very popular with his teachers. He planned pranks with his comrades and instead of following school lessons, he preferred to draw. When he ran out of paper to draw with, his leather pants would be used for it. Thanks to the intercession of Pastor Johann Jacob Wirz (1694–1773) from Rickenbach with his father, Graff was allowed to attend the drawing school in Winterthur, founded by Johann Ulrich Schellenberg in 1752, from Easter 1753 to 1756 . Graff became friends with his son Johann Rudolf Schellenberg . They practiced together, for which Schellenberg's large collection of paintings, hand drawings and plaster models, which he had inherited from his father-in-law Johann Rudolf Huber , offered them plenty of visual aids. Several portraits date from this period, including a self-portrait and the portraits of his father (inscribed: "Anton Graff / Winterthur 1755"), his younger brother Hans Rudolf and his brother-in-law, the master carpenter Johannes Vögeli.

After completing the first year of his apprenticeship, Anton Graff was able to choose a particular branch of painting, landscape painting or portraiture . The latter seemed to Graff from a financial point of view more advisable in order to obtain a secure source of income. He knew from Johann Ludwig Aberli that when he had little money he would resort to portrait painting.

Graff became the favorite pupil of Johann Ulrich Schellenberg, who was close to him. Artistically, Graff was soon superior to his teacher, which he also recognized. Schellenberg helped Graff after his apprenticeship with recommendations to his painter colleagues. Above all, Graff owed his teacher his conscientiousness in the craftsmanship and the “true, undisputed enthusiasm for art”.

Years of study and traveling

augsburg

After his training in Winterthur, Graff switched to the etcher Johann Jacob Haid in Augsburg in 1756 on the recommendation of his teacher Schellenberg , who was unable to find him a job, but said that “if Graff dared to come to Augsburg on his own, he would stand by him with advice and deeds ”. Haid granted Graff an apartment and board, introduced him to his artist friends and gave him orders. It was through him that Graff met his former teacher Johann Elias Ridinger , with whom he maintained regular contact. There Graff also painted the portrait of his compatriot and friend Christian von Mechel , who was completing his technical training in the studio of the copper engraver Johann Georg Pintz (1697–1767).

It was Graff's talent that the demand for good portraitists was great in Augsburg. Graff's art was very popular with his customers. Nevertheless, he had to leave Augsburg after a one-year stay because some of the masters of the painters' guild resident there complained “that the young stranger would open them to them, and demanded that he, according to well-established statutes that degrade art to a craft, renounce his employment or the city must evacuate ”.

Ansbach

Thanks to Haid's intercession, the court painter Johann Leonhard Schneider (1716–1768) in Ansbach became Graff's new master from 1757. Graff reported about him in his autobiography , written in 1778 : “His portraits had a lot of good things about them, fleetingly painted but similar. Since he painted very quickly and cheaply, he had much to do at this court and had to keep journeymen. I was very useful to him, copying and doing other trivial things with nothing to learn. At that time it was the time of the Seven Years' War and everyone wanted the portrait of the King of Prussia. The king's sister, the widowed Margravine Friederike Luise , had a portrait of the king that had been painted in Berlin. I often had to copy this picture and I finished one every day. Of course, I had no opportunity to advance in art; Always making bad copies is not the way to go. I saw it and I wouldn't have stayed so long if I hadn't enjoyed life in this house. Schneider and his family were pleasant, but no matter how much money he earned, he got into debt so that he had to end his life in prison. "

Nevertheless, Graff in Ansbach was able to benefit in terms of his artistic development. Johann Caspar Füessli said: “Graff had to spend most of the time copying; but he lost nothing there. It brought him a finished brush and a light and beautiful treatment in drapery, lace and other circumstances serving to make a portrait. "

Graff often traveled to Munich to study paintings , where he studied the collections in the Schleissheim gallery with great interest . There, in the spring of 1763, accompanied by Johann Jacob Haid , he got to know and appreciate the Bavarian court painter George Desmarées personally, whose works, characterized by Dutch realism, Venetian coloring and French accounts, attracted Graff because of their shimmering softness and light-flooded colors.

In addition to Desmarées, Antoine Pesne , whose portrait of Fridericus he copied many times, and Johann Kupetzky and Hyacinthe Rigaud had a decisive influence on the young portraitist. He owed Pesne the elegant security and noble restraint in coloring and image structure, while Kupetzky owed the intensity in the reproduction of the real, unvarnished personality. Graff judged the two family paintings painted by Kupetzky in Bayreuth Castle , which he had visited at the end of March 1766 when he was traveling to Dresden from Augsburg: “In the two family paintings by Kupetzky there is traditional nature, nothing ground, life itself; all other paintings that you look at afterwards become dull and flat. ”Confronted with such works, Graff gained the decisive starting point for his further work.

Two days before Margrave Karl Alexander von Brandenburg-Ansbach had Graff's master Johann Leonhard Schneider imprisoned in Ansbach for his unpaid debts in February 1759, Graff received a letter from Johann Jacob Haid with the offer to come to him again in Augsburg, because his main opponents died, which Graff accepted.

Augsburg and Regensburg

In Augsburg he first painted a portrait of the young Johann Friedrich Bause , who also worked for Haid. From that point on, Graff and Bause had a lifelong professional and private friendship. In March 1764 Graff met his future father-in-law Johann Georg Sulzer for the first time in Augsburg while he was traveling from Switzerland to Berlin. He was accompanied by Johann Caspar Lavater , Felix Hess , Johann Caspar Füessli and Christoph Jezler , who wanted to continue his studies with his compatriot Leonhard Euler . Graff agreed to show Sulzer and his companions the sights of Augsburg, whereupon Sulzer invited Graff to visit him once in Berlin.

In August 1764 Graff moved to Regensburg , where, in addition to the miniature paintings that had come into fashion, he also created some large-format pictures for the Swedish , Russian and Prussian ambassadors. As a result, he came into contact with people of the highest social position and was able to make pan-European connections. A talented young portraitist like Graff quickly found important friends and supporters in Regensburg, where the Reichstag met permanently. B. the Prussian comitial envoy Erich Christoph von Plotho , his daughter, the Baroness von Plotho, whom he portrayed there in 1764.

Court painter in Dresden

The offer

In February 1765 Graff was back in Augsburg, where he was visited by the Zurich citizen Captain Johann Heinrich Heidegger (* 1738 in Zurich; † 1823 in Livorno ). Heidegger was a bailiff at the Fraumünster in Zurich, a bookseller and co-owner of the Konrad Orell & Co. printing company and a lover of the fine arts ; as such, he owned an important collection of paintings. On his trip through Germany in Dresden, he had learned from Christian Ludwig von Hagedorn , the general director of the Dresden Art Academy , that he was looking for a portrait painter for the academy. Heidegger recommended Graff for this position, although Graff had initially turned it down because he didn't think he had any chances.

On his first visit to Switzerland after nine years in autumn 1765, Graff traveled to Winterthur and Zurich, where he painted various portraits, including those of Elisabeth Sulzer and his lifelong friend Salomon Gessner , Heidegger's brother-in-law. There Graff learned from Heidegger that he had recommended him to the academy director Hagedorn without his knowledge, who was looking for capable teachers for the important portrait subject.

On October 3, 1765, Heidegger wrote to Hagedorn: “On my way back to Augsburg I met a young man, Graff, from Winterthur in Switzerland. He paints to the taste of Desmarées and is really strong in his art. I don't know anyone of this kind in the academy. Perhaps he would come if he knew his establishment; With a view to his moral character, he is the most moral artist I know (...) ”In his letter of November 1, 1765, Hagedorn wrote to Graff:“ If you wanted to try your luck in Dresden, you would do so so that you would not be completely uncertain If you come here, the court would paint you at least three portraits with your hands on them, and give you free quarters for as long as you would like each portrayal, whether it be met with the greatest approval or not, with or without a hand with fifty thalers, and if the picture two Hands, with one hundred K. Kulden [convention guilders] or 66 Rthlr. Have 16 groschen paid (...) "Hagedorn offered him 100 thalers travel allowance and went on to say," if he would be applauded, he would be offered 400 thalers a year, otherwise he should nonetheless receive the travel money and the amount for the pictures. "

Graff hesitated because he did not consider his art good enough to be at the service of the Dresden court. In addition, he did not want to jeopardize his chances in Augsburg, where he had just started to establish himself as a portraitist.

Heidegger then sent Graff's self-portrait as a test piece to Hagedorn in Dresden, who responded to this suggestion and reported to the prince administrator Franz Xaver of Saxony about his progress in hiring a portrait painter for the art academy: “The portrait painter Graff was first out of distrust in his strength his own very similar portrait, which he painted some time ago, meanwhile, as someone else notes, he has made himself stronger in art, sent from Zurich and will then await the confirmation or the attribution of the last gracious command in awe. "

On January 16, 1766, Graff's self-portrait arrived in Dresden and was so well received that Graff received the call to Dresden that Marcello Bacciarelli was originally to receive.

Conditions of employment at the art academy

On January 17, 1766, Christian Ludwig von Hagedorn formulated his proposals for the terms of employment for the Prince's administrator Franz Xaver of Saxony. These promised Graff the appointment as court painter for an annual salary of four hundred thalers as well as one hundred thalers travel money. In return, Graff had to deliver his photo and an annual portrait for the court free of charge; A financial framework was set out for the payment of further court portraits. In addition, he had to train at least one apprentice a year without additional pay.

Hagedorn's proposals were approved by the court and Hagedorn immediately sent his letter of appeal to Zurich, where Graff was staying with Salomon Gessner. In February 1766, the letter reached Johann Heinrich Heidegger, who immediately sent it to Graff. Graff was overjoyed. At the beginning of March 1766, Graff traveled to Dresden via Augsburg and Bayreuth.

When he said goodbye in Switzerland and on his journey through Augsburg, some friends were immortalized in Graff's family book , including Johann Caspar Füessli, pastor Johann Jacob Wirz, Johann Jacob Haid and Johann Elias Ridinger . His friend Heidegger from Zurich wrote him the following lines:

"I, bone, quo virtus tua te vocat, i pede fausto, grandia laturus meritorum praemia. Quid stas? "

Arrival in Dresden

On April 7, 1766, Graff arrived in Dresden, where he lived on the Altmarkt as an electoral Saxon court painter and an aggregated member of the Dresden Art Academy . His apartment, a large room that he lived in almost until the end of his life, was in the house of Mrs. Magdalena Sophie Weinlig, widow of Dresden mayor Christian Weinlig (1681–1762). Years later, Carl Maria von Weber created the opera Der Freischütz in the same house in 1820 . Regarding Graff's arrival in Dresden, Johann Caspar Füessli stated: “Graff came happily to his destination and was introduced by Herr von Hagedorn to the high-ranking gentlemen who accepted him very graciously and immediately gave his brush the opportunity to look at their portraits To acquire fame and honor. He also succeeded as he wished; because he was lucky that his work exceeded all expectations. Everyone tries to use their talents and to let them grind them. ”And Graff said:“ From that time on I was always happy; I had a lot of portraits to paint. "

Annual exhibition

As a Saxon court painter, Graff had to work for Elector Friedrich August III. fulfill certain portrait assignments every year. These portraits for the court as well as for other Saxon nobles who held high positions in the state paved the way for Graff's reputation and success; it soon became a matter of good form to have Graff portray you. His paintings were shown regularly at the exhibitions founded by Hagedorn, which opened annually at the Art Academy on March 5th, the name day of Elector Friedrich August, and lasted 14 days. They contributed significantly to the fame and fame of Graff and also brought him orders. When Anton Graff first exhibited in 1767 and presented his portraits of Feldzeugmeister Aloys Friedrich von Brühl , Postmaster General Adam Rudolph von Schönberg and Colonel Johann Gustav von Sacken , among others , he received a lot of praise.

Life position as a professor

Various letters from this time between Graff and his father-in-law Johann Georg Sulzer show that Graff seriously considered leaving Dresden for Leipzig or Berlin from 1773 until the end of 1774 . In a letter dated November 11, 1774, Sulzer offered him to seek a pension from the King of Prussia, should he decide to settle in Berlin. He went on to say that he certainly had the hope of receiving the king's pension for him, but that went hand in hand with limited travel for Graff. "It is not acceptable here for those who have pensions from the king to travel outside the royal lands without express permission." This could have been one of the reasons why Anton Graff did not want to serve the Prussian court . Because Graff liked to travel, always back to his home country, Switzerland.

After the death of Christian Wilhelm Ernst Dietrich in 1774, his salary was divided among the teachers of the academy, Graff received an increase in salary of 50 thalers per year and at the same time the assurance of the court in Dresden that he would be able to travel for several months a year without having to travel beforehand Having to seek leave. His annual salary from the Saxon court was always paid on time, which Graff attributed to the elector's love of order.

Anton Graff kept the job in Dresden throughout his life. He turned down a specific offer from Berlin in 1788. At the beginning of the year, during a stay in Berlin, the Prussian minister Friedrich Anton von Heynitz made him the offer of the court to settle in Berlin with a salary of 1,400 thalers in order to work at the local art academy. His friend and business partner Daniel Chodowiecki also encouraged him to change location.

When Friedrich August von Zinzendorf , the Saxon envoy in Berlin, learned that Graff did not immediately accept this tempting offer from Berlin, he was impressed, as can be seen from a letter to Count Camillo Marcolini , Hagedorn's successor as General Director of the Dresden Art Academy since 1780 :

"Monsieur Graff, occupé ici depuis quelque temps à peindre le Roi , la Princesse Frédérique , fille du Roi, et d'autres personnes de marque est reparti aujourd'hui pour Dresden. Je sais qu'on lui a fait ici des propositions très avantageuses que jusqu'à présent il n'a point accepté, et je crois de mon devoir de rendre compte à Votre Excellence de cette preuve de zèle et d'attachement, comme devant donner you relief au mérite de ce célèbre artist. "

(German for example: "Mr. Graff, who has been working here for some time, painting the king and his daughter Friederike as well as other high-ranking personalities, has returned to Dresden today. I know that he was made very advantageous employment offers here until the very end, which he did not accept at all; and I consider it my duty to bear witness to Your Excellency of this proof of the fulfillment of duty and devotion, as if to make the merits of this famous artist even more vivid. ")

Graff asked for a time to think about his decision, sought a conversation with Marcolini and described the brilliant offer from Berlin and his financial situation at the time in a letter dated May 7, 1789: “(...) As difficult as the great gratitude towards S. electoral prince Your Highnesses, who have given me the most gracious protection and support for so many years, and the inclination, to which I confess with all my heart, to regard Saxony , in which I felt so well, out of a patriotic feeling as my second fatherland , must make every decision to change - so I must not behave appropriately that I also owe myself and as a husband and father of my family duties that should not be less sacred to me (...) "

Marcolini responded promptly. On June 20, 1789, according to the electoral Saxon resolution, Graff became professor for portraiture at the Dresden Art Academy with a salary of 700 thalers and 50 thalers a year for lodging. In his letter to Graff dated July 6, 1789, Chodowiecki expressed his joy about his promotion to professor and the associated financial allowances: “May you enjoy your health for a long time. Nevertheless, I am annoyed by the naughtiness of our minister [Friedrich Anton von Heynitz], who had the power to hire you, had he offered you R. [Reichstaler] 1,500, perhaps - if you had accepted and the king would certainly have approved his offer. "

Graff's academy colleagues included Giovanni Battista Casanova , brother of the writer and adventurer Giacomo Casanova , the portrait painters Christian David Müller , Johann Eleazar Zeissig and Johann Heinrich Schmidt .

There were far more manufacturers and artists in Dresden than in many other German royal cities . Graff liked this leading bourgeois element. This was probably another reason why Graff remained loyal to his adopted home - despite tempting offers from outside - throughout his life. Although he liked to travel extensively, he never made it to Italy, France, England and the Netherlands. However, he was able to study the masters from these countries in the Dresden picture gallery , which he liked to visit for his diversion; for “when the world shrank him back”, he could forget all suffering while contemplating these works. But in the end, as Graff himself admitted, “I was always happy”.

On July 18, 1807, Graff was introduced to Napoleon Bonaparte , who was in Dresden, by Count Marcolini and shortly before that , the elector who had advanced to become king :

“Then the King came, took our old Count by the arm, and led the worthy old man, whose heart burned high, to the great Napoleon. 'Sire! This is one of the most worthy members of our academy, the painter Anton Graff! ' - 'In which genre?' asked Napoleon. 'In portrait.' A gentle, lovely smile of applause on the part of the Emperor when he praised the King did the old, deeply touched artist well into his heart. So the real good is worthwhile everywhere and real merit is recognized, honored and honored: there is no need for intrusiveness! The artists whose works caught Napoleon's gaze were particularly Carlo Dolci , his Cäcilia and Herodias, as well as his Christ. "

to travel

Berlin

Graff often traveled to Berlin, where he quickly enjoyed great popularity and won many customers. He ended his autobiography , written in 1778, with the sentence: “I owe a lot to Berlin.” His father-in-law Sulzer introduced him there to personalities from the Prussian court. In his apartment he portrayed Gotthold Ephraim Lessing on behalf of Reich between September 20 and 29, 1771.

Carlsbad

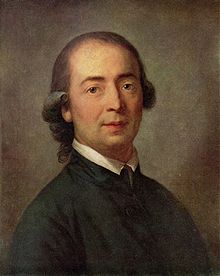

In the summer of 1785, Graff traveled from July 9th to August 10th 1785 to Karlsbad , where he portrayed Count Stanisław Kostka Potocki , Johann Gottfried Herder and Michael Hieronymus Prince Radziwiłł . It is very likely that Graff met Elisa von der Recke, Hanns Moritz von Brühl and his wife Johanna Margarethe Christina, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Charlotte von Stein during this stay , who celebrated the birthday of Leopold Friedrich Günther von Goeckingk there .

Switzerland

During his work as court painter in Dresden, Anton Graff visited his original home in 1781, 1786 (accompanied by Adrian Zingg ), 1796 and 1810/1811. As can be seen from various letters, he was a welcome guest with his friends and relatives in Zurich and Winterthur . He maintained particularly close contact with the family of his friend Salomon Gessner in Zurich.

During his last stay in Switzerland, the bookseller Heinrich Gessner (* 1776), son of Salomon Gessner, tried to convince Graff to write down the numerous anecdotes he could tell about the learned and distinguished personalities he portrayed, or Ulrich Hegner to tell so that he could write it down. Graff never complied with the request.

Portraitist of the personalities of his time

→ List of the people portrayed by Anton Graff

Anton Graff portrayed over 800 faces in his own unmistakable way - realistically powerful, with a conscious emphasis on the bourgeois-human aspect. His art was very popular among broad classes. He received numerous commissions from the nobility , diplomacy , science and the bourgeoisie .

Portrait of Frederick the Great

In 1781 Anton Graff painted Friedrich the Great . A replica of the picture that used to be in Charlottenburg Palace is exhibited in the death room of Frederick the Great in Sanssouci Palace.

Frederick the Great has not sat as a model since his coronation in 1740, with perhaps one exception (1763). For this portrait, Graff had to be content with Friedrich's sketches, which were made possible for him from a shorter distance during the troop parades of 1781. The result is a largely idealized image of the king, one of the most effective and expressive portraits of Friedrich. It shows the king in deliberately plain clothes, except for the order of “bourgeois” clothes, as a good-natured father of the country with an intense look, a forehead illuminated by a spotlight and an implied smile.

The art historian Saskia Hüneke assigns the picture to the age type of the Friedrich portraits, which are characterized by large eyes, distinctive nasolabial folds and narrow lips. His contemporaries considered it that of the many Friedrich portraits that comes closest to reality. The original portrait was shown at the Berlin anniversary exhibition in 1886 and has been lost since 1898.

In a letter to Friedrich Nicolai dated August 23, 1786 , Bause reported on a portrait of the king created by Graff, which Philipp Karl von Alvensleben , Prussian envoy in Dresden and Prussian cabinet minister since 1791 , owned : “(...) The painting is owned by Prussian ambassadors in Dresden: he and everyone who saw it think it is particularly similar. Mr. Graff painted it five years ago when he was in Berlin, went to the parade every day, marched to the monarch, which gave him the opportunity to see him very closely, and went straight to his lodgings at any time to color his picture . "

Anton Graff's picture is the most copied and reproduced portrait of Frederick the Great. Graff himself made replicas. Even Andy Warhol , one of the most important representatives of American Pop Art , estimated Graff Art. He used the picture as a template for his 1986 screen print with the portrait of Frederick the Great. The picture is one of a series of pictures of famous personalities that Warhol has been working on since the beginning of his artistic career in the 1960s. The Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg is presenting one of five existing copies of the Warhol print in Sanssouci Palace.

Secondary use of Graff portraits on postage stamps

Graff's portrait was used for a definitive stamp for the Deutsche Reichspost and for two special postage stamps for the Deutsche (Federal) Post: 1986 on the 200th anniversary of Frederick the Great's death and in 2012 on the 300th birthday of his.

Definitive stamp of the Deutsche Reichspost 1926

Special postage stamp of the Deutsche Bundespost for the 200th anniversary of the death of Frederick the Great (1712–1786). Design by Elisabeth von Janota-Bzowski

Deutsche Post special stamp for the 300th birthday of Frederick the Great. Design by Gerhard Lienemeyer

Special postage stamp of the Deutsche Bundespost for the 250th birthday of Johann Gottfried Herder based on the portrait from 1785

Postage stamp from the Republic of Moldova (2007) after a copper engraving by Johann Gotthard von Müller of the Schiller portrait by Anton Graff

Portrait of Friedrich Schiller

Friedrich Schiller arrived on September 12, 1785 at the house of the Körner family in Dresden, with whom Anton Graff was close friends and from whom he had already portrayed numerous members. The few portrait sessions with Schiller also took place there.

Anton Graff reported on the portrait, begun in spring 1786 and completed in autumn 1791: “The greatest distress, but ultimately also the greatest joy, was the portrait of Schiller; it was a restless ghost who, as we say, had no meat. Now I love it very much when people don't sit motionless across from me like Oelgötzen, or even make interesting faces, but friend Schiller drove my unrest too far; I was obliged to wipe out the outline already drawn on the canvas several times, since it did not keep me still. At last I succeeded in locking him into a position in which, as he assured him, he had not sat all his life, but which the Körner ladies declared to be very appropriate and expressive. He sits comfortably and thoughtfully, with his head tilted to the left on his arm; I mean the poet of Don Carlos , from whom he predeclaimed to me during the sessions, to have grasped in a happy moment (...) "

Christian Gottfried Körner's wife Minna helped Graff to bring Schiller into an appropriate calm posture, at least for some of them, during the portrait sessions, and said about the assumed pose: “We chose this position in which we had overheard him in lonely hours, mainly because of it to compel him to be calm; usually his head was bent back a little defiantly. Graff was satisfied that Schiller sat him about four times, so that he could finish painting his head and hands, at least put on the rest (...) "

Schiller wanted to make his wife happy with the picture for Christmas 1790 and asked Körner from Jena in a letter of December 17, 1790 to induce Graff to let him have the still unfinished picture for at least a few days: “I would love to wish to make my wife happy for Christmas with the Graff painting of mine; she calls for it indescribably. If it is not finished right away, Graff can leave it in my hands for a while, until we come together, which cannot wait for so long - and then he can finish it (...) ”With a letter of December 24, 1790 shared Körner Schiller with: “I would have loved to have helped you to please your female; but Graff does not hand the picture out of his hands unfinished (...) "

The portrait was finally completed in the summer of 1791. On September 12, 1791, Körner wrote to Schiller from Dresden, who had not seen it yet: “(...) Graff has finished your picture and will be releasing it in the next few days. As Graff tells me, you have already given the picture to Frauenholz . So Frauenholz won't let me go if you don't write him about it. By the way, if I were certain that you would come here next year and have yourself painted again, he would like to keep the picture. The upper part is good, but you should have sat down to the lower part. Now it is too vague (...) "

Popular portraitist

Anton Graff knew how to deal with the restlessness that Schiller displayed during the portrait sessions, as well as the peculiarities of many other customers, with humor and his much-mentioned “Swiss patience”. At that time, Graff had long been a sought-after artist. He was never able to fulfill all of the portrait assignments brought to him and so he could choose his clientele.

Even princes had to wait for an appointment with the highly esteemed artist. On May 3, 1777, Sulzer sent his son-in-law a letter with a bundle of orders with the request that he should not wait too long to carry them out and not let him, Sulzer, "as has already happened a few times" with his promise to Prince Heinrich , who finally wanted to be painted. Sulzer stated: “The prince would certainly take it highly, and I would have nothing but bitter annoyance from it. You can convince me if you come back at the promised time and not in autumn (...) "

Graff answered Sulzer's request and stayed from April 12 to June 27, 1777 in Leipzig and at Rheinsberg Castle , where he portrayed Prince Heinrich of Prussia as a war hero in armor , with the command baton in hand.

Esther Brandes as a role portrait

According to Berckenhagen, the portrait of the actress Esther Charlotte Brandes is the first representative German role portrait that depicts a moment of dramatic action. It shows the moment when Ariadne on Naxos , embodied by Esther Charlotte Brandes, overcomes the painful realization of seemingly hopeless abandonment. At that time it was enthusiastically reported that the Brandes wore the first "real ancient Greek" dress in the theater. Graff was given the honor of presenting her portrait to Brandes on New Year's Day 1776 on behalf of the Dresden audience. The picture was shown at the exhibition of the Dresden Art Academy, which opened on March 5, 1777 .

Johann Georg Meusel commented on the genesis of this portrait as follows:

“In consideration of the painting to be made, Mr. Graff not only attended a performance by Ariadne on Naxos, but also had the most elegant positions repeated in the room by the actress and, after careful examination, found the most skilful one in which Ariadne is actually painted . It is the point where she is sadly convinced that she has been abandoned by her Theseus , where the main interest of the piece begins, which from now on always increases the higher the fear and terror grows in the latter. It is therefore not a pain that has already been cried out; Rather, Ariadne stands there as if lost in misery, completely stunned by horror, amazed at this unexpected fate. There is no trace of calm here, but all the signs of extreme embarrassment are present. "

Until 1789, the portrait of Esther Charlotte Brandes was verifiably still in the possession of Johann Christian Brandes , as can be seen from his letter to Anton Graff on January 22, 1789. After that, the traces of the original portrait are lost, which must have come from the family through an estate arrangement or other means.

The new fashion à la grecque , with which Graff celebrated a success in the portrait of Esther Charlotte Brandes in 1776, however, displeased the elector:

“This is how he once painted the Electress , and gave her an ideal, or as it was called then, Greek robe, just as he had not long before painted the actress Brandes as Ariadne with approval; the picture was found to be very pretty, and one could not live to see the hour when the elector was to inspect it; but this, a serious gentleman who did not like to see his wife in theatrical garb, unwillingly passed by the portrait, called it à la grecque, and did not look at the painter. "

Iffland affair

With his amiable, cheerful and entertainingly pleasant demeanor, Graff also had to endure the peculiarities of his customers, for example Schiller's impatience or the unreliability of making appointments. Graff also sometimes worried about paying for the pictures he delivered. The actor August Wilhelm Iffland was of the opinion that he did not have to pay for his portrait, which shows him in his role as Pygmalion (in the melodrama by Jean-Jacques Rousseau ), since it was undoubtedly an honor for Graff to be allowed to portray him . Graff took it with humor and jokingly considered making a second portrait of Iffland in which he would portray him in his role as Pygmalion, as he really was. Because Graff said that he ennobled Iffland in this portrait very much so that he would not appear ridiculous in this role. Graff went on to say that the rumor of such a possible portrait would move Iffland to pay. Supported by his friends, Graff reserved legal action against his debtor.

“(…) But in general he [Graff] found what everyone thinks that a portrait painter is a troubled man because he so often subordinates his taste to tasteless fashion and has his outlines determined by the tailor and hairdresser, and cannot do what he wants. Meanwhile, whoever has a name can avail himself of several degrees of freedom. When he [Graff] once painted an old, elegant lady, he couldn't please her, but for a long time he submitted with great serenity; But when she finally demanded that he should stop in the middle of his work and consult with another painter and a cavalier , he, who, although a Swiss, did not like to take ad referendum, ran out of patience; he painted a mustache on her and ran away ”.

Pricing and payment behavior

The price for a portrait by Anton Graff depended on the size as well as the material and decorative details. When making portraits in uniform, the elaboration of details in badges of rank and medals or the detailed reproduction of a harness was reflected in the price. The same was true for the portraits of women. Elaborate fabric samples, different materials such as fur or lace and other decorations such as jewelry had to be paid for separately. The portrait also became more expensive if the hands of the person being portrayed were to be visible, whereby the price per visible hand was understood.

The appointment of Anton Graff as professor for the portrait subject at the Dresden Art Academy on June 20, 1789 had an impact on the prices he could ask for his work. Graff was one of the most sought-after and most valued portraitists of his time. While in Augsburg he first asked 20, later 30 guilders for a portrait (bust or hip) and increased his price to 30 thalers in Dresden from 1766 to 1789 , he now asked 50 thalers for a portrait without hands and up to 100 thalers, both hands should be visible.

Unlike some other artists, Graff never got paid for his paintings in advance, even though he was taking a risk. Because the payment behavior of his customers was not always the best. After the paintings had been delivered, Graff often had to warn his clients to pay. In the event of payment delays from his customers, Anton Graff could count on the help of his loyal friends. Daniel Chodowiecki did not let anything stop him from demanding Graff's fee for the portrait of Queen Elisabeth Christine , which was delivered to Berlin in July 1789 , from the beginning of September 1789 to the beginning of February 1790 . Finally, the payment of 16 Louis d'or 1790 took place. It also happened that he received no payment at all, as for example with the aforementioned portrait of the actor August Wilhelm Iffland .

Self-portraits

Graff painted over 80 self-portraits , which he often gave away to friends and patrons or created on behalf of customers and patrons . Since the self-portraits of the highly esteemed painter were in great demand among collectors, he made numerous replicas due to the great demand.

Another reason for taking so many self-portraits was his interest in the physiognomy of humans and their changes due to the aging process . Graff was constantly striving to perfect his art, his self-portraits also served him for self-study.

The later German President Theodor Heuss dedicated a study to Anton Graff in 1910. Among other things, he stated: “Dresden has a self-portrait. There he sits in front of the big screen, turns his upper body boldly and uninhibitedly towards the viewer and puts his arm lightly over the back of the chair, as if someone had stepped into the room while he was working and he was now examining it, without intending to himself continue to disturb. A delicious picture with an infinitely light and secure spatial effect. This self-portrait breathes a beautiful, phraseless self-confidence and serenity, and one understands his style, then one knows that Graff is not only present for the formal and aestheticizing art historian, but in his work as in his own human being a concise, sharp formula of the best Kind of representing his period. In a certain sense it is historical documentary material. "

Anton Graff presented this self-portrait in 1795 at the annual exhibition at the Dresden Art Academy . Presumably from the estate of Carl Anton Graff, the painting was purchased in 1832 for the Dresden Gemäldegalerie .

Goethe had already commented on a partial replica, a hip portrait of this self-portrait, which Graff had probably created shortly after the full portrait, when he visited Johann Gotthard von Müller in Stuttgart on August 30, 1797 , who was busy creating this hip portrait for Johann To engrave Friedrich Frauenholz in copper:

“I found Professor Müller'n in the graffiti portrait that Graff himself painted. The head is quite excellent, the artistic eye has the highest brilliance; I just don't like the position in which he leans over the back of a chair, all the less since this back is broken and the picture seems to be perforated below. The copper is also on the way to becoming very perfect. "

Image composition

In his portraits, Anton Graff always concentrated on the essentials, on the face of his counterpart. In particular, his attention was the eyes as the most important source for capturing a person's personality . The eyes shine out as the main and focal point of Graff's portraits. Graff's painted faces are life-affirming despite all the differentiation of the characters. No grief, but also hardly a smile dominates the features. They are enlightened , self-confidently calm adults, citizens without sensitivity and pathos .

Graff usually painted the subjects to be portrayed in simple and natural positions. If the body is turned slightly to the left or to the right, the eyes are looking straight at the viewer. If the body is seen from the front, the gaze is directed to the left or right. The head and body are rarely evenly turned towards the viewer or evenly seen in profile. The arms either hang freely or are laid one on top of the other, or one arm hangs down while the other's hand is hidden in the unbuttoned waistcoat or the pocket of the skirt.

Graff waived in his portraits largely on allegorical accessories and exaggerated staffage . Graff liked to paint life-size busts with a neutral background, with or without hands. He only painted hands for half-length portraits or the format of the half-length figure when he thought it would be worthwhile, for example for artists or beautiful women. Johann Caspar Füessli already remarked: "Noble features, and correct drawing in his head, beautiful shapes in his hands, and a brilliant and strong color, are parts that make Graff valued."

Salomon Gessner , who had sent his son Conrad (1764–1826) to Graff in Dresden to complete his training as a painter, instructed his son in a letter dated September 5, 1784 to paint a head every now and then throughout the winter to copy hands as much as possible after Graff: "(...) these latter are one of the most difficult parts, and which is neglected by very many (...)"

Graff used to prepare and design his portraits in pencil, chalk or charcoal drawings, some of them in their original size. He also made studies for certain details such as hands and arms, legs and feet and any accessories.

If the format of the picture permitted, Graff indicated the status of the depicted by adding characteristic accessories or by choosing a characteristic situation. He usually painted himself looking attentively at the person to be portrayed, chalk pencil or brush in hand. He put the engraver at a table on which the copper plate and grave mark lie. The art lover holds a drawing, the educated lady a book. The aristocrat in the knee or in full figure usually stands in uniform in a wide landscape, one hand on the basket or on the hip, the other holding his hat or in his pocket. Graff had the order, a representation of a portrait of a member of Sovereign House paint, he indicates this in a with a drapery provided interior with the symbols of his profession such. B. Kurhut , ermine coat and command staff .

Graff did not completely renounce elegance, pose and idealization; his portrayal of Friedrich II is cited as an example . However, one looks in vain for exaggerated flattery at Graff. In the 18th Book of Poetry and Truth , Goethe praised the honesty and accuracy of the portrait of Johann Jakob Bodmer (1781/1782) with his almost toothless head dominated by huge eyebrows. This portrait caused a sensation at the Anton Graff exhibition in the Eduard Schulte Gallery in Berlin in 1910, amidst the other depictions of well-groomed men with wigs, because of its realism.

Graff as a characteristic

Graff always endeavored not only to accurately portray a person's outward appearance, but also to give their personality and mental impulses a graphic form. So wrote Johann Georg Sulzer in his Encyclopedia General Theory of Fine Arts: "I have more even notice when that various persons who, by our Graff, the exquisitely has the gift of the whole physiognomy presented in the truth of nature have, grind who can hardly stand the sharp and sensitive looks he throws at her; because everyone seems to penetrate into the interior of the soul. ”Similarly, another contemporary reported about him in the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung of 1803:“ Graff meets, as one might say, in a higher sense; he does not paint the body but the spirit and almost always knows, with an incredibly happy tact, to seize the moment when not just one or the other characteristic peculiarity but the whole individuality of the interior is reflected in the calm exterior. ” Johann was also of this opinion Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim , who wrote in his letter of May 22, 1785 to Elisa von der Recke , “He has now made a vow never to be painted again, except by Graff or Darbes [Joseph Darbes (1747–1810)] , these soul painters ”.

In its edition of May 16, 1808, the newspaper for the elegant world reported on Graff's contributions to the exhibition of the Dresden Art Academy in 1808. Among other things, Graff exhibited a portrait of his friend and business partner Johann Friedrich Bause , who as a copperplate engraver 45 portraits reproduced by him and thus made known to a broad public:

“(...) Our venerable veteran Graff had painted his daughter with her child and her husband, the excellent landscaper Kaaz just mentioned , and here, too, did not deny his old fame of being a character. - But Professor Bause liked the portrait even more, full of speaking expression (...) "

In the 18th Book of Poetry and Truth, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe praised the honesty and accuracy with which Anton Graff had portrayed Johann Jakob Bodmer in 1781/82:

"(...) Fortunately, there is the picture after Graff von Bause, which perfectly depicts the man as he appeared to us, with his gaze of contemplation and contemplation."

Anton Graff preferred to portray people he had known for a long time or whose behavior and peculiarities he had been able to observe for some time before creating a portrait. Ulrich Hegner commented: “If Graff was able to interact with the people he was supposed to paint for some time beforehand, he liked it; then he listened unnoticed for her best expression, observed her peculiar posture, and studied the most natural and most suitable color tones of the face together, in order to apply all of this to the picture afterwards so that it does not become an uncharacteristic work, as is usually provided by handcrafted portrait painting (...) "

The portraits sometimes commented on the slightly idealizing style of the portraits in their own way. On July 24, 1787 , Schiller wrote to Körner about the Herder portrait that he made in Karlsbad : “I come from Herder. If you have seen his picture at Graff's, you can imagine him quite well, only that in the painting he is too light-hearted, more serious in his face (...) He is not very satisfied with his picture of Graff. He fetched it for me and made me compare it with him. He says that it looks like an Italian abbe. "

Lessing wrote in a letter dated July 29, 1772 to his future wife Eva : “You know that I had to let Graffen paint me in Berlin last year (...) Do I look so devilishly friendly?” Dieudonné Thiébault was from him Portrait that he saw in Sulzer's apartment, so captivated that he wrote about it:

“Je citerai une anecdote qui prouve combien M. Graff était un bon peintre. J'allai un jour causer avec M. Sulzer , dont l'appartement était à la suite du mien: je le trouvai avec M. Béguelin , [Nicolaus von Béguelin (1714–1789), Prussian civil servant, director of the philosophical class of the Academy of Sciences zu Berlin], à regarder un grand tableau qui était à peine achevé. Ce tableau me frappa singulièrement: mes yeux s'y reporter toujours malgré moi. “Voilà,” me dit M. Béquelin, “un morceau de peinture qui paraît vous occuper beaucoup: dites-nous ce que vous en pensez.” - “Je parie,” lui dis-je, “que ce n'est pas un portrait de fantaisie, et que de plus il est très ressemblant. "-" Et sur quoi en jugez-vous ainsi? "-" Sur ce qu'il me semble y découvrir la vérité de la nature, plutôt que les compartiments ou les caprices de l'art. ”-“ En ce cas, dites-nous l'idée que ce portrait vous donne de l'original. ”-“ L'original doit être un homme de beaucoup d'esprit, mais d'un esprit actif , très-vif et ardent: son caractère participe à ces mêmes qualités, et a de plus une fermeté remarquable, et une gaité très naturelle. Il est bon enfant, ami des plaisirs, et loyal; quoique d'une autre part il y ait du danger à heurter ses opinions ou ses préjugés. ”-“ Vous le connaissez donc? ”-“ Non; je n'ai jamais vu l'original de ce portrait. "-" Eh bien, vous venez de le dépeindre comme si vous aviez passé votre vie avec lui: c'est le portrait de M. Lessing , que M. Graff vient de faire. "-" C'est, "dis-je," un compliment pour M. Graff, car je n'ai jamais vu M. Lessing. ""

Masters of light and drapery

Anton Graff knew how to work with light and shadow. Johann Christian Hasche also recognized this when he wrote in 1784 while looking at a portrait of a gentleman made by Graff:

"(...) colored until life in a power of light and shadow that one believed to see true nature."

In Graff's portraits, the light is always directed towards the face, with a focus on the forehead. If his model was a lady, he also paid due attention to her cleavage . This way of painting goes back to his time in Ansbach, where he had the opportunity to study paintings by Johann Kupetzky . When looking at Kupetzky's pictures, Graff became aware of the problem of lighting, the alternation of light and dark, the balanced relationship between the protruding face and the background that lay behind. In his work, the austere, purely human-oriented style of Kupetzky's portrayal, often freed from everything courtly and conventional, in which the bourgeois becomes absolute reality, found expression.

During his time in Ansbach, Graff also came into contact with portraits by Hyacinthe Rigaud . The exemplary reproduction of the material, the velvet and the silk of the French court painter became his model. Graff knew how to reproduce fur as well as various material materials, namely velvet and silk, and their folds realistically. In 1765/1766 he portrayed Elisabeth Sulzer sitting in a blue silk manteau , trimmed with silver braids and a collar and borders made of gray-brown fur.

Gustav Parthey wrote about the creation of the portrait of Elisa von der Recke, step-sister of Dorothea von Biron and patroness of Anton Graff's later son-in-law Karl Ludwig Kaaz, from before 1790 : “She once had dinner at Nicolai's with Goeckingk , Zollikofer and other notables , and had to go to the court afterwards. With her left she picked up the train of her gray silk dress, made a graceful greeting with her right and said: 'Well, gentlemen, I must recommend myself.' Enthusiastic about the indescribable dignity of this apparition, Goeckingk exclaimed: 'This is how Graff must paint it!' This idea was actually carried out later (…) “Three versions of the portrait are known, the order of which is unclear.

Anton Graff's artistic development

Portrait painting

Graff's artistic development essentially took place in four phases. The first phase, which lasted until the end of the 1760s, served the search for personal form. For his portraits, Graff usually chose the chest or waist piece, frontal or with slight turns to the side, as the type of representation. He used bright, sometimes brightly contrasting colors that were sharply delimited from one another without transition.

The Graff little beloved wigs of Rococo gradually disappeared and the place of the subtle sense of life, coupled with noble-delicate sensibility and lightness, occurred from around 1760 the virtues of Classical . In painting, nature was idealized in its beauty, since the works of art should not only be beautiful and noble, but also educating. This epoch corresponded to Graff's nature, whereby he already went a step further and did not idealize nature, but represented it realistically. Graff can be seen as the portraitist in the German-speaking world who, with taste and success, achieved a certain realism in portraiture.

Graff's second phase began with the numerous portrait commissions from Philipp Erasmus Reich . It marked the turn towards a conscious realism. The colors became warmer and more subdued and plunged into a harmonious light and dark. The face - as the center of the portrait - blended softly into the ensemble. It was the phase of the lasting influence of Johann Kupetzky .

Graff's third phase began in the late 1770s and extended to the dawn of the 19th century. Above all, the influence of his English and partly also French painter colleagues becomes visible here. Graff switched to bright, lively, cool colors. The colors were now connected to each other and to the background in a harmonious way. His style of painting became large-format, more lively and also somewhat sketchy. Especially for knee and full portraits, which were more common in this phase, landscapes now served as a background, just as it was fashionable in England. Showpieces and showpieces were only created when princely personalities had to be portrayed. Graff produced actual parade and representation paintings primarily on behalf of the courtyards of Dresden and Berlin as well as circles close to these courtyards. Group pictures were rare; In addition to his own family pictures, the one of the family of Rittmeister Ludwig Wilhelm von Stieglitz from around 1780 is probably the best known.

In the fourth phase, Graff turned back more to the format of the chest and hip pieces, perhaps also with regard to his eyesight. The colors became darker, impasto powerful in the application and through colored shadows floating in the transitions. Graff's painting technique now seems almost impressionistic .

Landscape images

The first signs of the later emerging Impressionism are also visible in his landscape paintings, which he began to paint in his later years. Philipp Otto Runge and Caspar David Friedrich were influenced by his landscape painting.

Around 1800 Anton Graff painted The Elbe near Blasewitz above Dresden in the morning ; the Graff family spent the summer months in Blasewitz. There Graff's daughter Caroline Susanne met her future husband Karl Ludwig Kaaz in 1796 . Graff gave the picture to his friend Daniel Friedrich Parthey . According to his son Gustav Parthey , Graff had told his father “that he had never painted landscapes before and that he was bored during a summer stay in Loschwitz ; then he thought that if you could hit a constantly changing head, you would also hit a still landscape ”. A copy may have been made by his son Carl Anton Graff and was once in Elisa von der Recke's apartment in Dresden; on this copy the willow tree is on the right edge of the picture.

The descriptions of Elisa von der Recke's Dresden apartment by Konstantin Karl Falkenstein in the work Christoph August Tiedge's Life , edited by him, refer to other landscape pictures by Graff, which contains his biography and poetic work. There it says: “If you had crossed the cheerful stone-paved courtyard of the almost rural house, the stairs led into a spacious anteroom, the walls of which were adorned with several landscape paintings by the famous court painter Anton Graff, which depict natural scenes from the area from Dresden, when: the villages of Loschwitz, Blasewitz [presumably this painting by Blasewitz was the copy that was possibly made by Carl Anton Graff after the original of his father], the Plauischen Grund , etc., and so on deserved more attention, since the great portrait painter only devoted himself to studying landscape painting at a later age and, as it were, only for his recreation and also created ingenious works in this field (...) "

Otto Waser wrote about these four landscape pictures : “They are intended to illustrate the four times of the day with their changing moods. The Elbe area above Dresden, this river landscape with an early morning mood, is definitely on top . The moonlight landscape, the night piece, Blasewitz near Dresden is the dark side piece to it and similarly large and uniform in the lecture : how untouched was this place, made famous by Schiller ! In addition to these masterly counterparts , both of which seem equally closed, and collected linearly in an oval, the other two pictures, noon and evening, appear more pettier and less uniform, with more individual works and more details, also in form, so that one for them would like to assume an earlier origin: bright sunshine lies over Plauen near Dresden, evening mood over the entrance in the Plauenschen Grund . "

Silver pen drawings

According to his own statements, Anton Graff created a total of 322 silver pen drawings between 1783 and 1790 in the manner of the French painter Jean-Baptiste Carvelle , who had rediscovered this old technique, which was already widespread in the 15th century. These are drawings on parchment leaves with a silver pen, which have been dusted with pumice stone and carmine powder to give them a delicate tint. On the occasion of his bathing stay in Töplitz in 1783, Graff had the idea of making such miniature drawings as well. Graff made most of these silver pencil drawings there and during his stays in Karlsbad and his travels to Switzerland.

In a letter dated October 27, 1784, Daniel Chodowiecki thanked Graff for such a silver pen drawing with the portrait of Graff's wife Guste with the words: "(...) You brought this manner much further than Karwell (...)" Also Chodowiecki himself as well as the painter Joseph Darbes (1747–1810) were avid imitators of Carvelle.

The drawings were very popular and Graff was able to sell them for three ducats each. In 1790, Graff had to stop making silver pen miniatures due to his diminishing eyesight.

Business and private contacts

In 1769, Anton Graff became friends with Philipp Erasmus Reich , a Leipzig bookseller and publisher who ran the Weidmann bookstore from 1746 to 1787 and became a reformer of the German book trade . Rich hired Johann Heinrich Tischbein and Anton Graff to make portraits of his learned friends. This was done with the aim of bringing together a gallery of the most famous contemporary poets and thinkers, based on the model of the portrait collection in Halberstadt's Gleimhaus , the temple of muses and friendship of Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim . Graff painted a total of 26 portraits for Reich, including those of Christian Fürchtegott Gellert , Christian Felix Weisse , Moses Mendelssohn , Gotthold Ephraim Lessing , Johann Christian Stemler , Christian Ludwig von Hagedorn and Karl Wilhelm Ramler . Reich was Graff's largest single client. When his widow Friederike Louise Reich, b. Heye, who moved to her hometown Berlin, donated most of the portrait collection of the Leipzig University Library in 1809 as part of the 400th anniversary of the University of Leipzig .

Graff was a sociable fellow. Surrounded by friends and living in happy family relationships, he always won the pleasant side of his life - regardless of whether it was Burgundy wine , for which, according to the entry in his writing calendar of February 12, 1801, 37, Spent 5 thalers, or about boat trips on the Elbe , about repeated visits to the Leipzig trade fair or about happy round tables. One of them in May 1809 caused the writer Friedrich Christoph Förster to describe Graff as follows: “(…) It was a lively old man, the powder did not reveal whether the hair was mottled, gray or perhaps already white. Even though he was wearing glasses, his eye stars flashed through the glasses. He wore a brown silk tailcoat with large steel buttons, Brussels cuffs and bosom stripes, a flowered blue silk vest and seemed to be happy to accept the politeness that his neighbor, Mrs. Seydelmann , made him about his toilet (...) "

Graff cultivated friendships with many of the personalities, business partners and colleagues portrayed by him, including the painters Salomon Gessner and Adrian Zingg as well as the engravers Daniel Chodowiecki and Johann Friedrich Bause , who reproduced numerous portraits of Graff, which made his art known to a broad public. Graff was also in contact with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , whom he met in Dresden in 1768. In 1778, Goethe accompanied Duke Karl August von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach and Prince Leopold von Dessau incognito to Berlin and took the opportunity to visit Graff on May 16 in Berlin, who was working there and with Johann Georg Sulzer in Heiligengeiststrasse 7 lived in the back building of the Knight Academy.

Graff and his friend and compatriot Adrian Zingg, who had also been appointed to the Dresden Art Academy in 1766 , were reminded of their homeland, the Swiss Jura , by the landscape there . They often made joint excursions to this area, which they called Saxon Switzerland to distinguish it from their homeland , which is how they gave the area its current name. Previously, the Saxon part of the Elbe Sandstone Mountains was called the Meißner Hochland, Meißnisches Oberland or Heide over Schandau . “From their new adopted home they saw a mountain range to the east, about a day's walk away. It showed a strangely flattened panorama, without any actual peaks (...) "(). Wilhelm Leberecht Götzinger took up the name coined by Graff and Zingg and made Saxon Switzerland known throughout Europe through his books.

Graff portrayed Adrian Zingg in the Loschwitz area , with a view from above of the Elbe and the right bank of the Elbe, whose row of hills disappears in the haze. In the background, two of Zingg's students serve as accessories . On one of their first trips together to “Saxon Switzerland”, Graff and Zingg drew brochures from Königstein Fortress . Some law enforcement officers found this suspicious and they arrested the two Swiss. The misunderstanding seems to have cleared up quickly, because there were apparently no further consequences.

Private life

Wife and children

Through the mediation of Philipp Erasmus Reich , who took on the role of free recruiter for his friend Anton Graff , Graff married Elisabetha Sophie Augusta Sulzer, called Guste, daughter of Johann Georg Sulzer on his 51st birthday on October 16, 1771. It was one for Graff Easy to get the father's consent to marry. Sulzer himself is said to have said about Graff, "that he found a soul in Graff that was as pure and as bright as the most beautiful spring day." That at the beginning of the marriage the young wife lived together with the 17 years older husband was not always easy, as evidenced by various letters between Anton Graff and Sulzer, who was always well-disposed towards him and treated him like a son.

Graff and his wife had five children, three daughters and two sons. Johanna Catharina Henrietta (born November 16, 1772) died soon after giving birth. Another daughter was born before April 3, 1779 and died, the third daughter Caroline Susanne (born September 15, 1781) married the painter and Graff student Karl Ludwig Kaaz. Graff's sons were the later landscape painter Carl Anton (* January 1, 1774 - † March 9, 1832, godfather was Adrian Zingg ) and the future court trainee Georg (* January 1777, † July 1801).

Anton and Guste Graff (born December 7, 1753 in Berlin, † April 26, 1812) were married for over 40 years. During this time, Graff repeatedly portrayed his wife and other family members. At the end of 1812 he wrote to a friend in Switzerland, to whom he had previously sent some paintings: “I wanted I had brought the pictures myself, so I would be with you, where I would like to be now, because the good times for me lost here on land. I also believe that I would suffer less from the loss of my wife than I do here. If I keep my life and health, maybe a quarter of an hour will be saved for me in Winterthur on this short career (...) "

On 20./21. May 1813 the battle of Bautzen occurred . After that, over 17,000 injured people were housed in Dresden, some in town houses, as the hospitals were insufficient. Graff therefore left his apartment and moved in with his daughter Caroline Susanne. From there he wanted to leave the city, besieged by the French, for Switzerland. Graff, who had been operated on for a cataract in 1803 and was now almost blind and used a magnifying glass to paint , wanted to spend the rest of his life in Winterthur. In the last month of his life he told a Swiss friend about the situation in Dresden, which was occupied by Napoleon Napoleon's troops:

“You haven't heard from me for about six months because you couldn't write or travel. Our situation here is sad, incessant billeting, restlessness and fear of losing everything in danger. For a year, my dear friend, I have not been a happy old man; if I could see an opportunity to come to Switzerland myself, I would still dare at my age, I cannot live long in these troubled times; I think it is quieter with you than here; Heaven forbid that the theater of war doesn’t move into your area! "

death

Anton Graff died shortly after moving to his daughter on June 22, 1813. His two children announced their father's death with the following advertisement in the Leipziger Zeitung :

“On the evening of June 22nd, around 8 o'clock, our dearly beloved father, Anton Graff, professor at the Königigl, passed away. Saxon. Painter's Academy, after 12 days of illness from nerve fever , 76 years old, 7 months old. We hereby make this event, which is so sad for us, known to all friends and acquaintances of the deceased from abroad, with the bitterness of all condolences, and we commend ourselves to your benevolence. Dresden, June 24th 1813. Carl Anton Graff, Caroline verw. Kaaz, b. Graff "

Ulrich Hegner reported on Graff's funeral procession: "A large entourage of professors and students accompanied him to the grave in the Bohemian churchyard in front of the Pirnaischer Tor ." At the funeral there was neither a hymn nor a necrology . Only the newspaper Der Freimüthige of 1813 announced the death of Anton Graff: "In these days Dresden has lost the veteran of Dresden artists, the brave portrait painter Professor Graff, a Swiss man." From the Dresden Art Academy in 1813 because of the chaos of war out any files. However, in a salary regulation from 1814, after Graff's name, the simple addition: "Has died."

Anton Graff used to let his relatives in Winterthur manage his assets. On his behalf, they lent his money against corresponding interest in Switzerland. As early as 1790, his younger brother Hans Rudolf administered the sum of 13,522 fl. 29 kr. , At the end of 1800 his cousin Jacob Rieter received the sum of 17,946 florins 36 kr. for Anton Graff. When he died in 1813, he left his two surviving children with a fortune of 40,000 thalers, which corresponds to around 2.5 million Swiss francs (as of 2013). Graff was thrifty, especially with himself, but by no means stingy. Many younger artists who enjoyed his hospitality and were encouraged by him, among them Louise Seidler , reported Graff's kindness and generosity towards them.

Anton Graff's descendants

Anton Graff's grave has not been preserved, the cemetery was closed in 1858. His two sons, trainee lawyer Georg Graff (1777–1801) and landscape painter Carl Anton Graff, were never married and had no children. After the death of his brother-in-law Karl Ludwig Kaaz in 1810, Carl Anton Graff took on the two underage daughters of his sister Caroline Susanne in a fatherly manner. One of these two granddaughters died years later in the Dresden Altweiberhospital . Anton Graff was closely related to Switzerland through his eight siblings.

Artistic estate

Anton Graff created around 2000 paintings and drawings. Much of his work has been preserved. He did not maintain a workshop, but it can be assumed that Graff's pupils were partly involved in the creation of replicas .

Ulrich Hegner published in 1815 in the XI. New Year's piece from the Zürcher Künstler-Gesellschaft Details about his life and creative path. According to this, Graff is said to have kept “a large [unfortunately lost] book”, “in which he recorded all his work from the beginning, with the names of the people depicted and the prices. It contains portraits 297 painted from 1756 to 1766 in Augspurg, Regenspurg, etc.; Original painting from 1766 to January 1813 in Dresden etc. 943, copies 415, altogether 1655 painted pictures. In addition, there are drawings with silver pen 322 mentioned above. “Hegner does not list the drafts and studies drawn in chalk, which should comprise several hundred pieces.

Carl Anton Graff's estate was auctioned off in Dresden in 1832 . According to the auction catalog, these included numerous works by his father, including a. Portraits of family members.

Anton Graff's own short autobiography , written around 1778 and allegedly copied by his son Carl Anton Graff, was owned by Karl Constantin Kraukling (1792–1873) in Dresden until 1884 . The further whereabouts are unknown. However, the wording of the autobiography has survived.

Replicas and copies

Replicas and own copies

Anton Graff made replicas of some of his works himself , which can vary in quality compared to the first version of a portrait and among each other. Some of them show changes in subordinate details. They can also make a somewhat flat and dull impression compared to the first version. When making replicas of Graff, it can be assumed that some of his students have worked with them.

In addition to his own works, Graff liked to copy works by other painters, especially in the Dresden picture gallery . As Graff's letter of March 3, 1797 to the land clerk Ulrich Hegner shows, he saw the making of copies more as an exercise or a source of income than as an independent work: “(...) I did not copy your portrait, partly due to lack of time, and partly because it is always a copy and an original is preferred (...) "

Graff was the preferred portraitist of the German, Russian, Polish and Baltic aristocracy. His most famous clients from these circles were Frederick the Great of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia , for whom he copied numerous pictures in the Dresden Gemäldegalerie in 1796 , including works by Pompeo Batoni , Carlo Cignani , Antonio da Correggio , Anthonis van Dyck , Raffael and Peter Paul Rubens . The empress even managed through her envoy that Graff was allowed to copy in original size, which was otherwise forbidden in Dresden. As a token of his appreciation for his work, Graff also received a 70 ducat gold medal from the Empress in addition to the agreed wages .

Copyists

The portraits of kings and princes as well as of scholars, poets, artists and other famous personalities were copied by other painters during Graff's lifetime. Carl Focke , Ernst Gottlob and Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Ferdinand Collmann were among the most famous Graff copyists . Several of these copies are still hanging in the Gleimhaus in Halberstadt today . Other Graff copyists were Heinrich Freudweiler , Johann Friedrich Moritz Schreyer , Wilhelm Gottfried Bauer , Gottlieb Schiffner , Johann Christian Xeller and Thomas Löw, who was also from Winterthur . Even Friedrich Georg Weitsch copied Xerox Graphical portraits. Weitsch also portrayed Graff twice. The ladies Hainchelin, a student of Daniel Chodowiecki , and Johanna Wahlstab copied pastel paintings by Graff . Both exhibited their pastel copies made after Graff in 1788 at the exhibition of the Berlin Academy of the Arts .

Contemporary reproductions

Over 130 engravers , mezzotints and lithographers reproduced and distributed Graff's works in numerous engravings. In particular, Baus' more than 40 masterful copper engravings and the etchings by Daniel Berger and Christian Gottlieb Geyser contributed a lot to Anton Graff's fame.

Anton Graff himself also etched in copper. A self-portrait, a portrait of his father-in-law Johann Georg Sulzer and the portrait of the businessman Detmar Basse can be verified . In Graff's etchings, a distinction was made between three different types of prints or states: in front of all writing, in front of the name and with the name of the person depicted. There were also ideas.

Graff's pupil

Anton Graff said of himself that he did not have the gift to train students. He lacked the patience to always answer questions from the students. Nevertheless, he gave private tuition to some students, mostly on the recommendation of colleagues, if he thought they were gifted. Graff was of the opinion that you either have the talent to be a painter and that you can improve and perfect this by only very diligent and frequent painting, or that you have no talent.

The most important student of Graff is Philipp Otto Runge , who came to Dresden in 1801 on the recommendation of Jens Juel . Graff and his family took Runge up like a son and promoted him. Further students were Georg Friedrich Adolph Schöner , Emma Körner , Karl Ludwig Kaaz , Carl Focke , Ernst Gottlob , David Angermann and Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Ferdinand Collmann . In addition, from May 1784, friends from Zurich, Heinrich Freudweiler (1755–1795) and Salomon Gessner's son, Conrad Gessner (1764–1826), stayed in Dresden with Anton Graff and Adrian Zingg for further training . Conrad Gessner later made a name for himself as a horse and battle painter. Heinrich Freudweiler became a landscape painter and also painted genre pieces .

From 1796 to 1798, the budding landscape painter and etcher Emanuel Steiner (1778–1831) , who came from Graff's hometown Winterthur , was Graff's pupil. Graff's son Carl Anton made friends with Emanuel Steiner. On June 27, 1801, the two went on a study trip together. This led them via Switzerland and Milan to Rome. Carl Anton Graff stayed in Rome until the end of 1807. During this time, father and son exchanged a lot of letters. In addition, Carl Anton repeatedly sent his father his work for appraisal. Because Carl Anton, who, like his father, did not devote himself to portrait art but to landscape painting, had learned the basic technical terms from his father. In Ludwig Richter’s opinion , no more than this - Richter sarcastically remarked that the young Graff had not inherited anything from his father’s talent.

reception

As early as 1768, Johann Heinrich Heidegger (1738–1823), Salomon Gessner's brother-in-law, recorded individual stages of Anton Graff's life and work in writing.

Two years later, Johann Caspar Füessli published his five-part series History of the best artists in Switzerland along with their portraits. In the third volume he reported for the first time in detail and based on conversations with Anton Graff on the life and work of the already famous court painter in Dresden and concluded his report with the words:

“(…) And how much does art have to expect from him! Because he is not satisfied with the fame he has achieved. The more he learns to understand what is part of the perfection of art, the more he feels obliged to redouble his diligence and reflection, to expand his knowledge of nature and the sublime patterns of the Dresden Gallery, and through such noble endeavors to expand his merits to enlarge, and one day to earn a position next to the greatest portrait painters. "

General director Hagedorn was also very satisfied with Anton Graff. In 1768 he proudly reported to Johann Georg Wille about the achievements of his protégé in a letter. Wille replied to Hagedorn: “I am extremely pleased that you have a great portrait painter in Mr. Graff. Mr. Bause recently sent me a small portrait, which he dug after Mr. Graff, from which I can see that his heads must be full of wisdom, which is based on a firm drawing and secure application of color. I think about all this and more with pleasure, because I suspect that great portrait painters must be a rare thing in Germany these days. The art here is to catch nature in action. Only a close observer can become familiar with this art. I believe that Mr. Graff is very capable of this observation. I have to love this artist ... "

How much Anton Graff was in demand as a portraitist can be seen in a letter from Daniel Chodowiecki . On October 27, 1784 he wrote to Graff in Dresden: “Our Berliners will do well if they let you paint them, because Berlin is now very much bared by good portrait painters. There is nobody more than Frisch who paints something bearable and he paints very slowly. ”And in his letter of January 6, 1785 to Christiane von Solms-Laubach , Daniel Chodowiecki described Anton Graff as the“ greatest portrait of Mahler of this century - it is one indescribable truth in (...) his pictures ”.

For posterity, Graff is considered the most important German-speaking portraitist of classicism, "whose brush", in the words of Johann Christian Hasche , "proves spirit and soul in the magic of the mixture of colors". Hasche also judged Graff's art:

“(…) In the meantime, every picture by Graff is always so beautiful that it completely throws everything that is called portrait down; because who is not known as our first portrait painter in Germany? "

Almost a hundred years later, Carl Clauss noticed:

“On the dead tree of the fine arts of that time, the portrait compartment was the only branch that still sprouted green, vigorous sprouts; Graff was the best among the good painters who had that subject at the time. "

Honors

On May 8, 1783, Anton Graff became an honorary member of the Berlin Academy of the Arts , in the spring of 1812 an honorary member of the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts and in the fall of 1812 an honorary member of the Munich Academy of Fine Arts . On the late honors of 1812, Anton Graff wrote in a letter at the end of the same year: "It is now too late, my artistic career is over (...)"

In autumn 1901, a memorial plaque was attached to Anton Graff's birthplace at 8 Untertorgasse in Winterthur. The house was later replaced by a new building. In honor of its famous citizen, the Winterthur Vocational Training School (BBW) named one of its school buildings after Anton Graff.