Saxon court

The Saxon court , also referred to in literature as the Dresden court , was the court of the Wettins in the Electorate of Saxony and the designated Kingdom of Saxony until the abdication of the last Saxon King Friedrich August III. 1918. The Saxon court represented the political and cultural center of Saxony in early modern society.

Tasks and assignment

The early modern court, tailored to the ruling prince, stands as a pillar of public tasks in the government of the Electorate of Saxony alongside the civil and military state .

In principle, every adult member of the Wettin ruling family held their own court. As a result, the number of servants in the Saxon court fluctuated according to the number of people living in the Wettin dynasty. The family members each had their own court masters , adjutants and court cavaliers , court ladies and court maids . After the husband's death, the wives of deceased electors or kings held their own so-called widow's farms , which were maintained from widow offices. The Saxon court was consequently a conglomerate of several courts and court holdings with the electoral or royal court in the Dresden residence as the center. The courts of the lower-ranking members of the ruling family remained dependent on the court of the prince.

The early modern court was, on the one hand, closely considered the living space and household of a princely family. Considered further, the court also includes all of the court offices , central organizational elements, whose task, in addition to supplying the ruling family, includes the government and administration of the ruled area. The prince's personal environment, the entourage, is also included . Together, these designate the court. Court rules regulated the daily routine at the court and the responsibilities of individual functionaries within their offices. The departments emerged from the requirements of economic provision and personal service to the prince and his family.

Personnel composition and development of offices

The court was made up of aristocrats and commoners who found access because of their civil service, as well as aristocrats who were doubly legitimized by their descent and office to reside at court. The yard ranking was used for classification . Within the court there was a large group of people who only held the title of chamberlain or chamberlain and did no service. Often these did not live in Dresden and therefore did not stay near the prince in the normal daily routine. They mostly appeared exclusively for larger celebrations.

The constitution of the Saxon court is closely connected with the emergence of permanent residences in the late Middle Ages. These replaced the dominant travel rule of the ruling prince. Under Elector Christian II , the court increased in pomp and size, while under the long reign of his brother Johann Georg I, the burdens of the Thirty Years' War also restricted the keeping of the court. Under Johann Georg I, the court was primarily the residence of the electoral family and only a secondary representative center of the country. Only under his son and successor Johann Georg II did the function of the court that had begun under Christian II again come to the fore.

In the heyday of absolutism , the court was the concentration of princely power internally and externally. The Saxon court from 1737 contained 712 servants. The Swiss Guard comprised 122 employees, the stable management 50 employees, the ballet and theater 44 employees, the court orchestra 65 employees, fire guards, carpenters, bricklayers comprised 42 employees, there were 20 employees of bedmasters and house men, the hunt had 57 employees 16 whistlers, 77 lackeys, Heiducken and runners, 20 court trumpeters, 30 page, language and exercise masters , 17 employees of the silver and light chamber, 10 employees of the Oberhofmarschallamt, 10 employees in the court confectionery and the provision house, 27 employees in the court cellar and 70 employees in the kitchen.

However, the court of Augustus the Strong never reached the size of the court of the Bavarian Elector Maximilian III. Joseph had nearly 1,000 people. The French court of Louis XIV in Versailles at times comprised 15,000 people and was therefore more than 20 times the size of the court of Electoral Saxony. Between 1763 and 1815 the Saxon court in Dresden had a size of 1200 to 1300 civil functionaries. This number sank to 981 by 1818 and in 1828 there were still 744 bourgeois at court. After 1831 the number of office holders increased again, in 1863 it reached 945 office holders. In contrast, the number of aristocrats, the so-called court aristocrats at the Saxon court, was 75 aristocrats in 1730, 150 aristocrats in 1770 and in the 19th century only 30 to 40 aristocrats.

The king's influence on the aristocratic class was therefore minimal, unlike in France, which under Louis XIV tied the nobles very strongly to the Versailles court in order to tie the French nobility to royal power.

In 1819, the Saxon court comprised the actual royal court with its residence in Dresden, the queen's court and 17 other courts of the princes and princesses with a total of 300 other people. In total, the Saxon court contained 1200 people in 1819. The offices of department heads in court administration were reduced from twelve to nine positions between 1763 and 1826. When the Swiss Guard was no longer deployed after the Napoleonic Wars , their captain ceased to be head of department. The office of master chef was considered an Oberhof charge and was awarded twice. The first of these positions was listed as vacant in the State Handbook from 1780 to 1826 before being deleted entirely. The second position only existed until 1797. Until 1866, however, most of the positions remained, these were:

- the office of the Oberhofmarschall ,

- the Lord Chamberlain ,

- the head stable master ,

- the chief hunter ,

- the thigh ,

- the chamberlain ,

- the house marshal ,

- the court marshal ,

- the master of ceremonies .

The Dresden court experienced a structural downsizing between 1800 and 1819, when 41 offices for forest and game masters , hunting junkers and pages were cut.

Since 1839, the position of “General Director of the Court Theater and the Musical Band” has been listed in the state handbooks as an additional upper charge. Since the introduction of the constitution of 1831 there was the Minister of the Royal House , who was subordinate to all previous court authorities and was responsible for the administration of the Royal Civil List. In addition, he was in charge of the family entailment and all personal, family and property matters of the royal family. In 1900 the court was only 619 strong.

Occasions and events

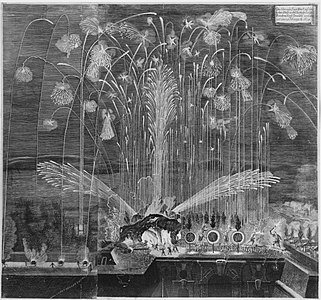

Court festivals were one of the essential characteristics of courtly splendor. They served as a medium for stately self-expression. At the same time, court festivals secured the court's position as the social, political and cultural center of the country. Events such as invitations to the lordly dinner table, audiences, assemblies , apartments and concerts, larger celebrations (state parliament openings , court balls , New Year's receptions) or gala days (birthdays, name days, wedding anniversaries in the royal family) shaped the annual processes at the Saxon court. They also served to bind the Saxon nobility to groups. Court festivals went back to a centuries-old tradition in Electoral Saxony, the opulence and splendor of which became famous beyond Saxony, especially during the Augustan era . At the end of the 17th century, costume parties arranged as role-plays were common during Carnival, so-called courtly masquerades . Court ballets and ballet masquerades , based on the model of the French ballet de cour , were also fashionable . Jousting games and parodies of tournaments , static sleigh games , animal baiting , pleasure shooting as well as drama performances by the traveling troops or the electoral comedians served as entertaining entertainment .

The importance of the Saxon electorate, which had grown due to the election of the Polish king in 1697, was to be taken into account with a pompous appearance. The court thus followed the current trend of the Baroque age , when the European princes strived for splendor, splendor and public representation. In addition to the court, some of the residents of the Dresden residence and the surrounding country also took part in the festivities as participants or spectators at the elevators. But also purveyors to the court and wage laborers who had to do the various orders of the court for such festivities in the factories and craft enterprises, benefited from it. The festivals and celebrations were partly prepared over months. The artistic design corresponded to the high social and political importance of the festivals. All available artists in Saxony were used to design the program: architects and painters as well as musicians, singers, dancers and poets, sculptors, goldsmiths and silversmiths. Balthasar Permoser , Alessandro Mauro , Louis de Silvestre , Johann Jakob Irminger , Johann Melchior Dinglinger , Johann Ulrich König , Jean de Bodt , Adam Friedrich Zürner , Johann Alexander Thiele and Johann Benjamin Thomae contributed with their creativity, ideas and works to Dresden until 1734 it became a residence of European rank due to the court festivals. The Saxon master builder Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann designed and built pleasure houses and pleasure ships for fireworks, the buildings and tents for the Zeithain pleasure camp 1730 and the Zwinger as a special architectural setting for all festivities.

As part of the baroque self-staging, the Saxon elector himself took part in the costume-making productions in various roles, for example as the disguised “Hercules Saxoniae” or the sun god Apollo , which was aimed at the princely claims to rule. After the death of Augustus the Strong, the courtyard festival culture changed from the ceremonial court to the court of muses . With Friedrich August II , the Italian court opera became a central element of the courtly festival culture.

The Zwinger and the Great Garden were the places of the festivities. On Pillnitz were on the same water festivals celebrated, the baroque garden was the setting for the celebrations for the award of the Polish Eagle Order . There was also a celebration in the parade halls of the Residenzschloss . Numerous artists stayed at August's court. Of the 365 days of a year, 50 to 60 days were celebrated. The others were politically worked, planned, administered and governed. During the first decades of the 18th century, around 25,000 thalers were earmarked in the state budget for festivals each year.

In the 19th century, a court ball comprised around 200 to 500 people who were admitted to the parade .

- contemporary copperplate engravings on occasions at the Saxon court

Stage design for the opera Camillo Generoso by Carlo Luigi Pietragrua in 1693 in the opera house on Taschenberg

List of courtly events

- 1662: four-week wedding celebrations on the occasion of the marriage of the Elector Princess Erdmuthe Sophie of Saxony to Christian Ernst of Brandenburg-Bayreuth in October

- ten divertissements at the Dresden court in the years 1660, 1661, 1663, 1665, 1667, 1669, 1672, 1677, 1678 and 1679. This series of events was founded by Elector Johann II. Georg .

- July 1668 and November 1679: two-week celebrations, so-called "peace festivals" on the occasion of the peace treaties in Aachen and Saint-Germain

- 1678: "Celebration for the most serene gathering", highlight of courtly festive culture during the reign of Johann Georg II, on the occasion of the summit of the Albertine dukes and their relatives in Dresden

- 1694: on the occasion of the accession of Elector Friedrich August II. Week-long festivals and masquerades

- 1695: first carnival of the reign of August the Strong

- 1697: Celebrations on the occasion of the coronation of the Saxon Elector as King of Poland

- 1709: Long festivities in Dresden during the visit of the Danish King Christian

- 1719: Saturnus Festival : four weeks and around four million thalers expensive celebration of the wedding of Prince Elector Friedrich August to the Habsburg Emperor's daughter Maria Josepha in September

- 1727: Celebrations to mark the recovery of King August II.

- 1728: Festivities during the Dresden Carnival on the occasion of King Friedrich Wilhelm I's state visit to Prussia

literature

- Vinzenz Czech: Princes without a land: courtly splendor in the Saxon secundogenitures Weißenfels, Merseburg and Zeitz. Writings on residential culture, volume 5. Lukas Verlag, Berlin 2009.

- Ute Essegern: Princesses at the Electoral Saxon court: Life concepts and life courses between family, court and politics in the first half of the 17th century. Leipzig University Press, 2007.

- Josef Matzerath: Trial of nobility at the modern age, Saxon nobility 1763–1866, deconcretization of a traditional social formation. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2006.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Josef Matzerath: Adelsprobe an der Moderne, Sächsischer Adel 1763-1866, deconcretization of a traditional social formation, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, p. 125.

- ↑ Ute Essegern: Princesses at the Electoral Saxon Court: Concepts of life and life courses between family, court and politics in the first half of the 17th century, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2007, p. 425.

- ↑ Ute Essegern: Princesses at the Electoral Saxon Court: Life Concepts and Résumés Between Family, Court and Politics in the First Half of the 17th Century, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2007, p. 35.

- ↑ Ute Essegern: Princesses at the Electoral Saxon Court: Concepts of life and life courses between family, court and politics in the first half of the 17th century, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ Josef Matzerath: Adelsprobe an der Moderne, Sächsischer Adel 1763-1866, deconcretization of a traditional social formation, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, p. 124.

- ↑ Ute Essegern: Princesses at the Electoral Saxon Court: Concepts of life and life courses between family, court and politics in the first half of the 17th century, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ Ute Essegern: Princesses at the Electoral Saxon Court: Life Concepts and Résumés Between Family, Court and Politics in the First Half of the 17th Century, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2007, p. 44.

- ^ Karl Czok: August der Starke and Kursachsen, Koehler and Amelang, Leipzig 1987, p. 212.

- ^ Karl Czok: August der Starke and Kursachsen, Koehler and Amelang, Leipzig 1987, p. 212

- ↑ Josef Matzerath: Adelsprobe an der Moderne, Sächsischer Adel 1763-1866, deconcretization of a traditional social formation, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, p. 125.

- ^ Karl Möckl: Court and court society in the German states in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Büdinger research on social history 1985 and 1986, Harald Boldt Verlag, Boppard am Rhein 1990, p. 187.

- ^ Josef Matzerath: Adelsprobe an der Moderne, Sächsischer Adel 1763-1866, deconcretization of a traditional social formation, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, p. 124f.

- ^ Josef Matzerath: Adelsprobe an der Moderne, Sächsischer Adel 1763-1866, deconcretization of a traditional social formation, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, p. 125f.

- ^ Karl Möckl: Court and court society in the German states in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Büdinger research on social history 1985 and 1986, Harald Boldt Verlag, Boppard am Rhein 1990, p. 188.

- ^ Vinzenz Czech: Princes without a land: courtly splendor in the Saxon secundogenitures Weißenfels, Merseburg and Zeitz, writings on residential culture, Volume 5, Lukas Verlag , Berlin 2009, p. 212.

- ^ Vinzenz Czech: Princes without land: courtly splendor in the Saxon secundogenitures Weißenfels, Merseburg and Zeitz, writings on residence culture, volume 5, Lukas Verlag , Berlin 2009, p. 214.

- ↑ Josef Matzerath: Adelsprobe an der Moderne, Sächsischer Adel 1763–1866, deconcretization of a traditional social formation, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, p. 126.

- ^ Vinzenz Czech: Princes without land: courtly splendor in the Saxon secundogenitures Weißenfels, Merseburg and Zeitz, writings on residence culture, volume 5, Lukas Verlag , Berlin 2009, p. 214.

- ↑ Reiner Gross: Geschichte Sachsens, Edition Leipzig, 5th edition, Leipzig 2012, p. 135.

- ↑ Reiner Gross: Geschichte Sachsens, Edition Leipzig, 5th edition, Leipzig 2012, p. 137.

- ^ Carsten cell: Enlightenment and court culture in Dresden, journal of the German Society for Research in the Eighteenth Century, Volume 37, Issue 2, Wallstein Verlag, Wolfenbüttel 2013, p. 186.

- ^ Carsten Cell: Enlightenment and Court Culture in Dresden, Journal of the German Society for Research in the Eighteenth Century, Volume 37, Issue 2, Wallstein Verlag, Wolfenbüttel 2013, p. 185.

- ↑ Reiner Gross: Geschichte Sachsens, Edition Leipzig, 2001, p. 136.

- ↑ Josef Matzerath: Adelsprobe an der Moderne, Sächsischer Adel 1763-1866, deconcretization of a traditional social formation, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, p. 127.

- ^ Vinzenz Czech: Princes without a land: courtly splendor in the Saxon secundogenitures Weißenfels, Merseburg and Zeitz, writings on residence culture, volume 5, Lukas Verlag , Berlin 2009, p. 216ff.