Hessian Ludwig Railway

The Hessische Ludwigsbahn (HLB) was one of the largest German private railways with a track length of 697 kilometers .

Locomotive No. 110, Gonsenheim of the Hessian Ludwig Railway

|

|

prehistory

Starting position

The Hessian Ludwig Railway was a product of the failed - or better: missing - railway policy of the Grand Duchy of Hesse for its province of Rheinhessen . While the province of Starkenburg received a central railway connection with the Main-Neckar-Bahn quite early and the province of Upper Hesse was at least marginally opened up by the Main-Weser-Bahn - the Grand Duchy held shares in both railways and they were operated as state and condominium railways - there was no corresponding development in the third province, Rheinhessen.

Since the state was not active here, this was the chance for private involvement in the form of a stock corporation . The seat of the Hessian Ludwig Railway was therefore not the capital Darmstadt , but the capital of the province of Rheinhessen, Mainz . The first impulses for a railway construction in Rheinhessen did not come from the locals, but from outside; French-Bavarian circles in particular were interested. For strategic military reasons, however, the Prussian state was opposed to this route on the left bank of the Rhine : With such a railway, French troops could be at the gates of Mainz within 10 to 12 hours. The Grand Duchy of Baden saw in the project competition both to the Main-Neckar Railway, in which Baden also held shares, and to the self-designed railway from Mannheim to Basel .

When the Bavarian government granted the concession to railway construction in the Palatinate (Bavaria) in 1844 , the northern continuation of the railway to Rheinhessen appeared attractive. The pioneer of the German railroad, Friedrich List , personally campaigned for a railroad construction from Mainz to Worms . The grand ducal government in Darmstadt initially stuck to its negative stance, especially since it had committed itself to a state railway system by law in 1842 .

The corporation

In the larger cities, "railway committees" formed from interested traders to promote railway construction. Those of Wiesbaden and Frankfurt am Main united in 1836. The Mainz Committee joined this combined committee in 1837. The goal was a railway from Frankfurt via Mainz-Kastel to Wiesbaden. This Taunus Railway began operating in sections in 1839/40, but - contrary to original expectations - in Mainz this meant that traffic was withdrawn from Mainz to the right bank of the Rhine.

As a result, a new committee was formed in Mainz on June 10, 1844 with the aim of founding a stock company for the operation of a railway from Mainz to the border with the Bavarian Palatinate south of Worms . A subscription to the future shares in the amount of 5 million guilders took place in Mainz and Worms for three days and was a complete success: 8.6 million guilders were subscribed, a considerable part of which was made by banks from Frankfurt, Cologne and Mannheim. Friedrich List expressly supported the project. Now the government in Darmstadt took a stand, on the one hand out of fear of competition with the state railway on the right bank of the Rhine , the Main-Neckar-Bahn, and also because there was a resolution by the estates that the railway should be built in the Grand Duchy as a state railway (which was Practice but only worked to a limited extent due to tight public finances). However, on March 8, 1845, the estates revised their previous resolution.

The founding meeting of the stock corporation took place on October 8 and 9, 1845. The Hessische Ludwigsbahn, initially Mainz-Ludwigshafener-Eisenbahngesellschaft , was named after the then reigning Grand Duke of Hesse , Ludwig III. from Hessen-Darmstadt . Anton Humann became the first president of the society .

Presidents:

- Anton Humann (1844-1854)

- Clemens Lauteren (1854–1867)

- August Parcus (1867–1875)

- Johann Kempf (1875–1888)

- Christian Lauteren (1888)

- Franz Werner (1888-1897)

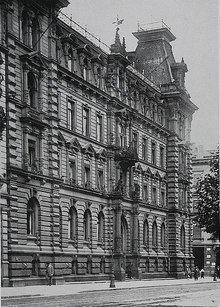

The administration of the railway, which was initially housed in the buildings of the first Mainz train station, was given a representative, new administration building near the new central station (today: Mainz main station ) in 1888 . The design came from Philipp Johann Berdellé , who had also planned the reception building of the Centralbahnhof . The headquarters building was later the Lauteren wing of the building of the Mainz Railway Directorate .

Route network

Main line: Mainz – Worms (–Ludwigshafen – France) (1853)

construction

As early as 1838, the Taunus Railway Committee examined the route between Mainz and the first Bavarian municipality, Bobenheim , in order to be able to estimate the costs. However, since the connection from the border to Ludwigshafen am Rhein (then: Rheinschanze ) was not guaranteed at the time, the project got stuck. In 1844 the Bavarian government granted the concession - also for a stretch from Ludwigshafen to the Hessian border near Bobenheim. This brought the old project from 1838 back to life. In addition, there was now a railway connection between Cologne and the Belgian seaports in the north and the Grand Ducal Baden State Railways had already pushed their Badische Hauptbahn up the Rhine valley . This meant that the ship transport between Cologne and Mannheim passed Mainz, and it was in danger of being disconnected in traffic.

The route was initially unclear. The alternative Mainz- Alzey- Worms was rejected in 1845 in favor of a direct route along the Rhine because it was shorter, without topographical obstacles and therefore cheaper to build and operate. The route via Alzey was later built as a Rheinhessenbahn (see below). On August 15, 1845, the public limited company was granted the state license to build railways, which was the basis for any necessary land expropriations. However, the concession also contained a number of conditions that had to be worked through before construction could begin. This included ensuring that the southern continuation of the railway would take place on Bavarian territory and an agreement with the administration of the Mainz fortress on how and where the local train station should be located. This was an administratively and structurally complex matter for the passage of the railway into the city because of the militarily important fortress belt that had to be preserved there.

As early as the beginning of 1846, Paul Camille von Denis (civil engineering) and the Mainz provincial master builder Ignaz Opfermann (structural engineering) - the latter was given leave of absence for this purpose - were hired as technical directors of the project. They initially estimated the construction costs at 4.68 million guilders, later this was reduced to 3.95 million guilders. The construction was then carried out by sacrifice man, while Denis was the railway director in the neighboring Palatinate. The construction work of the HLB began with the work on the Mainz train station in 1847 after the government of the Grand Duchy had determined on May 10, 1847 that all conditions had been met. However, it took another 26 February 1848 to obtain the building permit.

That everything was now financially and administratively clarified was of no use, because the German Revolution of 1848/1849 also brought with it a financial crisis. Since the shareholders had to gradually pay the amount stated in the shares in installments that were called, many of them no longer made their payments, but waived their shares and what had already been paid up. This led the corporation into a financial crisis. The railway construction stalled. Negotiations began with the government to take over the project as the state railway, which - including parliamentary debates - dragged on until August 9, 1852. The result was: the state bought newly created shares in the company for 1.2 million guilders, but these could not be sold until 1862. The agreement on the cross-border connection to the Palatinate was concluded almost at the same time. After overcoming these difficulties, construction proceeded rapidly, not least because the terrain in the Upper Rhine Plain was completely flat and larger engineering structures were not required. The 46-kilometer route went into operation in sections in 1853, progressing south from Mainz:

| section | Commissioning day |

|---|---|

| Mainz - Oppenheim | March 23, 1853 |

| Oppenheim– Guntersblum | July 10, 1853 |

| Guntersblum – Osthofen | August 7, 1853 |

| Osthofen– Worms | August 24, 1853 |

| Worms - Bavarian border - ( Ludwigshafen (Rhine) main station) | November 15, 1853 |

The costs for the railway construction and the initial equipment with operating resources amounted to almost 4.5 million guilders .

expansion

Initially, the line was only single- tracked and as scheduled , six passenger trains (including two express trains) used it daily in each direction between Mainz and Worms. In Mainz there was a connection to the steam ships of the " Cologne and Düsseldorf Companies " and via the Mainz – Kastel trajectory to the Taunus Railway to Wiesbaden , Frankfurt am Main and via the Main-Neckar Railway to the state capital Darmstadt .

On November 6th, 1853, the Hessian and Palatinate Ludwigsbahn signed a contract for cross-system traffic. After that, there was continuous passenger and freight traffic as well as luggage transport, there were continuous tickets and the company was supposed to appear like a railway in the external image . The cross-border section between Hesse and the Bavarian Palatinate went into operation a few days later, on November 15, 1853. Since that day, there was continuous rail traffic between Mainz and Paris , a connection that was offered three times a day and on which the express trains, which only carried first and second class, traveled around 17 hours. The link on the left bank of the Rhine to Strasbourg went into operation on October 22, 1855.

The space available for the station of the Hessian Ludwig Railway in Mainz was cramped. Located between the built-up area and the banks of the Rhine, it was able to be enlarged several times from 1859 onwards by redesigning the banks of the Rhine and connecting the railway to Bingen, but the conditions remained cramped. Only when the new Central Station, west of the city center, was opened in 1884, with access routes partly routed through tunnels , was the space problem resolved.

Rhine-Main Railway (1858)

HLB tracks and staff in the Main-Neckar train station in Darmstadt, 1867

|

But already with its second route, the Rhein-Main-Bahn , the Hessian Ludwigsbahn reached beyond the borders of the province of Rheinhessen and reached the state capital for the first time: in 1853 the grand ducal government approved the establishment of the bank for trade and industry in Darmstadt. Part of the conditions associated with the approval was that the bank should build the railway line between Bingen via Mainz to Darmstadt and Aschaffenburg . In 1855, the Ludwigsbahn and the bank signed a contract that transferred the building rights to the Ludwigsbahn, involved the railway in the bank and regulated the financing. The route initially led from Gustavsburg (today: Ginsheim-Gustavsburg) via Darmstadt to Aschaffenburg. In Darmstadt, it initially used four head tracks in the northeastern area of the Main-Neckar train station , a through station . It was not until 1875 that the HLB completed its own terminal station , which was also northeast of the Main-Neckar station. The Mainz – Gustavsburg trajectory initially operated between Gustavsburg and Mainz , which was replaced in 1863 by a fixed bridge (today: Südbrücke ).

Railway on the left bank of the Rhine (1859)

As early as the beginning of the 1840s, a railway committee was formed to aim for a route from Mainz to Bingen , which at that time was on the border between the Grand Duchy and the Kingdom of Prussia . The aforementioned contract between the Bank for Trade and Industry and the Ludwigsbahn from 1855 also gave the railway the right to build this route. The route was measured in 1857, and traffic began in 1859: goods traffic on October 17, 1859 and passenger traffic on December 27, 1859 . Today this route is part of the Left Rhine Route . With it, the last gap in the rail connection from Basel to Cologne was closed. The HLB now also connected the Rheinische Eisenbahn and the Königlich Bayerische Staatsbahn via the Rhein-Main-Bahn and thus Cologne, Munich and Vienna . In a letter dated January 27, 1863, the Grand Duke gave the Bingen – Mainz – Worms line the name Rheinbahn .

Municipal connection line Frankfurt (1862)

In addition to the routes it had built itself, HLB also tried to integrate third-party routes into its network. In 1862 the HLB took over the operation of the Frankfurt am Main municipal railway , the infrastructure of which, however, remained the property of the Free City of Frankfurt . This commitment has to be seen in connection with the takeover of the Frankfurt-Hanauer Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft and the management of the Frankfurt – Hanau railway line .

Frankfurt-Hanau Railway (1863/1872)

For the expansion of the compounds of HLB in the Rhine-Main area particularly in the direction was the province of Upper Hesse , an exclave of the Grand Duchy, the Rhine-Main area in the direction of Bavaria and by the Kinzigtal towards Bebra the railway line Frankfurt South Aschaffenburg high Interest. The route ran from the Hanau train station in Frankfurt to Hanau and on over the Bavarian border near Kahl am Main to Aschaffenburg .

The HLB therefore endeavored to acquire them since 1862. However, a merger failed because of the objection of the Kurhessischen state . Thus, the HLB took only the management of the Frankfurt-Hanau Railway Company for the period from 1 January 1863 to 31 December 1872. After the annexation of Kurhessen in the Austro-Prussian War could finally 1866, the Frankfurt-Hanau Railway Company 1872 merge into the HLB.

Main Railway (1863)

Messel train station around 1900; in the background the Messel paraffin and mineral oil plant

|

As a branch line from the Rhein-Main-Bahn in Bischofsheim , the line to Frankfurt am Main was opened in 1863 . In a letter dated January 27, 1863, the Grand Duke gave it the name Mainbahn . The HLB used the Main-Neckar station of the Main-Neckar Railway in Frankfurt . This station had already been expanded for this purpose in 1862. The HLB thus reached the Frankfurt railway junction from its main network and thus connected to the lines already operated by the municipal connection railway and the Hanau railway .

Rheinhessenbahn (1864/1871)

The Rheinhessenbahn Bingen – Alzey – Worms was opened in three different sections between 1864 and 1871. The end section of the Alzey – Mainz line was also used for the route.

Riedbahn (from 1869)

First construction phase

The Riedbahn was initially designed as a connection between the state capital Darmstadt and the city of Worms, which is also important for the Grand Duchy. In 1869 the line from Darmstadt via Goddelau and Biblis to Rosengarten was opened. From 1870 to 1900 the Worms – Rosengarten route crossed the Rhine here. On December 1, 1900, it was replaced by a double-track bridge over the Rhine , which enabled a continuous train connection. The previous terminus at Rosengarten was closed.

In 1975 the Darmstadt – Goddelau section was shut down due to lack of traffic and largely canceled. A track leads from Darmstadt to Weiterstadt- Riedbahn and ends there in an industrial track.

Second construction phase

On October 15, 1879, the route followed from Biblis via Waldhof to Mannheim's Neckarstadt . In Mannheim, the Riedbahn did not end in the main train station, but in the Riedbahnhof , which was north of today's Kurpfalzbrücke .

Third construction phase

On November 24, 1879, the section from Goddelau to Frankfurt-Goldstein was put into operation. The HLB was thus able to compete with the Main-Neckar-Bahn, which also reached Mannheim directly - without the detour via Mannheim-Friedrichsfeld . The importance the HLB attached to this route in north-south traffic shows that it subsidized the construction of the Gotthard Railway with 800,000 marks in order to secure future traffic. The connection was further "upgraded" by creating a bypass around Mannheim via Käfertal in the Rheintalbahn to Mannheim main station , whereby the Riedbahn was threaded from the south into Mannheim station.

Nibelungen Railway (1869)

The Nibelungen Railway has been connecting Worms with Bensheim on the Main-Neckar Railway since October 27, 1869 . The connection between Worms and Hofheim uses the Riedbahn. On April 1, 1903 - the HLB had already been nationalized at that time - a connecting line from Lorsch to Heppenheim on the Main-Neckar Railway was built. However, it was not economical to operate. Passenger traffic ended around 1936 and all operations were shut down in 1958 at the latest.

Mainz – Alzey (1871)

The Alzey – Mainz railway line was opened by HLB in 1871.

Taunus Railway (1871–1872)

The longstanding attempt by the HLB to bring the Taunus Railway under its control was granted only a brief success in 1871. With a contract dated November 14, 1871, HLB bought the Taunus-Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft . It acquired the oldest line in Hesse, the Taunus Railway from Frankfurt to Wiesbaden, the Sodener Bahn and the Curve – Biebrich railway, and took over their operations on January 1, 1872. But on May 3, 1872, the HLB resold the lines to the Prussian State Railways . In return, it received, among other things, a concession to build the Main-Lahn-Bahn from Frankfurt-Höchst in the direction of Cologne via Prussian territory.

Wiesbachtalbahn (1871–1895)

The Wiesbachtalbahn from Armsheim to Wendelsheim was opened in several sections between 1871 and 1895 by HLB.

Main-Lahn-Bahn (1877) / Ländchesbahn (1879)

Of the concession for a route from Frankfurt to Cologne via the Westerwald, only a section between Frankfurt-Höchst and Eschhofen - ( Limburg ) was implemented and opened in 1877, the Main-Lahn-Bahn . This route was supplemented

- 1879 to the connection Wiesbaden Ludwigsbahnhof - Niedernhausen , the so-called Ländchesbahn , and

- 1880 by an extension from Frankfurt-Höchst via Griesheim to Nied , where a connection was made to the Frankfurt municipal line , which in turn flowed into the Hanauer Bahn .

Alzey – Bodenheim (1879/1896)

The Alzey – Bodenheim railway line went into operation in two construction phases on October 1, 1879 and October 1, 1896 as an access railway for the towns between the main lines.

Odenwald Railway (1882)

The Odenwaldbahn with its parts:

- Eberbach –Wiebelsbach-Heubach (since 2006: Groß-Umstadt Wiebelsbach),

- Wiebelsbach-Heubach – Darmstadt and

- Wiebelsbach-Heubach-Hanau

was passable in all sections from 1882. In terms of engineering, it was probably the most complex railway that HLB built. Above all, it opened up the economically disadvantaged mountain region of the Odenwald . Due to the difficult topography, it could never become important as a competitor to the existing north-south connections in the Rhine Valley.

Line numbers

At the beginning of the 1890s, the HLB assigned line numbers for its route network:

- Line 1: Frankfurt – Hanau – Eberbach

- Line 2: Darmstadt – Wiebelsbach-Heubach

- Line 3: Mainz – Alzey

- Line 4: Armsheim – Wendelsheim

- Line 5: Bingen – Alzey – Worms

- Line 6: Mannheim – Worms via Lampertheim

- Line 7: Bingen – Mainz – Frankfurt

- Line 8: Mainz – Worms

- Line 9: Mainz – Darmstadt – Aschaffenburg

- Line 10: Frankfurt – Hanau – Aschaffenburg

- Line 11: Frankfurt – Limburg

- Line 12: Wiesbaden – Niedernhausen

- Line 13: Frankfurt – Mannheim

- Line 14: Darmstadt – Worms

- Line 15: Bensheim – Worms

nationalization

HLB generated a considerable part of its profits through agreements with neighboring railways, according to which traffic was routed as long as possible on its own routes. This business model no longer worked after Prussia nationalized the railways under its own jurisdiction. The HLB now bordered in the north exclusively on the network of the Royal Prussian State Railways , whose aim was to offer the cheapest possible tariffs for the economy. The HLB, which is tiny compared to the huge state railway, could not do anything to counter this.

The HLB drastically reduced the maintenance of its facilities and vehicles and increased the dividends of its shareholders in return. Since the compensation of the shareholders in the case of nationalization based on the provisions of the concession deed was based on the surpluses achieved in recent years, the shareholders exploited the railway in two ways. The receiving states had to settle the bill.

In Hesse, the factual takeover of HLB by Prussia was controversial, whereby from the Hessian point of view primarily the loss of sovereignty was to be complained about, while the economic advantages were obvious. For example, the industrialist from Worms, Cornelius Wilhelm von Heyl, vehemently advocated nationalization, as the HLB was reluctant to approach the contractually agreed construction of a bridge over the Rhine near Worms and did not expand the Worms train station sufficiently. Heyl was an influential politician in the Grand Duchy and at the same time a member of the Reichstag and the first chamber of the Hessian estates .

The HLB was nationalized by a state treaty of July 23, 1896 and a takeover agreement between the two states and the HLB. The shareholders were compensated with 89,520,000 marks . By the highest decree of March 17, 1897, a “ Royal Prussian and Grand Ducal Hessian Railway Directorate” was established in Mainz on April 1, 1897, which took over the administration of the nationalized railway. As a result, the HLB became part of the Prussian-Hessian Railway Operating and Financial Community , which the vernacular commented on with " H och l ebe B ismarck" . On April 8, 1899, employees were prohibited from wearing the old HLB uniforms.

Vehicle fleet

Locomotives

The Hessian Ludwigsbahn started operating with 6 locomotives from the Esslingen machine factory , which - as was customary at the time - had illustrious names: "Schenk" (after Freiherr von Schenk , director of the Hessian Ministry of Finance), "Dalwigk" (after Freiherr von Dalwigk , then Hessischer Ministerial Director and previously Mainz Territorial Commissioner - this locomotive pulled the inaugural train on the Mainz – Oppenheim line, "Gutenberg" (named after Johannes Gensfleisch , " Johannes Gutenberg ", the inventor of the art of printing ), "Arnold Walpoden" (after Arnold Walpoden , the initiator of the "Rhenish Confederation" in 1254) as well as "Mainz" and "Worms".

In 1861 the HLB had 39 locomotives and in 1864 52 locomotives. At the end of 1895, one year before the Hessian Ludwig Railway was nationalized, there were 216 locomotives.

Steam railcar

HLB achieved a pioneering achievement with the use of three Thomas type steam powered rail cars , which had been developed at HLB based on a design by chief engineer Georg Thomas . The vehicles were equipped with all three car classes in the lower area . The upper area was a third class large room. Four window axes were available in the lower area and the seats were arranged in four compartments 2 + 3, with the third class and the upholstered classes each forming an open-plan compartment with two window axes. In the upholstered class, the seats on the side on which they were wider were assigned to the second class, on the narrower side to the first class, where they were designed as small individual compartments with additional doors opposite the aisle. One of the two first class compartments was reserved for "women". The third class had 60 seats and the upholstered class 20 seats.

The vehicles were initially used on the Odenwald Railway between Darmstadt and Erbach , and from 1881 between Rosengarten, Mannheim and Bensheim. As a rule, they operated with two or three other attached cars.

Fleet

In addition to eleven passenger cars , first and second car class included 19 passenger cars of the third class, as well as 36 baggage and freight cars to the initial stock (a fourth vehicle class is omitted).

At the end of 1895, one year before the Hessian Ludwigsbahn was nationalized, there were 544 passenger cars, 107 baggage cars, 1552 covered and 2240 open freight cars.

Worth knowing

- The building files and other historically valuable documents of the Ludwigsbahn were burned in the Second World War , the duplicate of which was lost during the evacuation by train in Bavaria. The Hessian State Archives in Darmstadt also suffered considerable losses in the Second World War.

See also

literature

sorted alphabetically by authors or editors

- Reinhard Dietrich : A railway is opened . In: Der Wormsgau 33 (2017). ISSN 0084-2613 . ISBN 978-3-88462-380-0 , pp. 111-126.

- Hans Döhn: Railway policy and railway construction in Rheinhessen 1835-1914 . Mainz 1957.

- Konrad Fuchs: Railway projects and railway construction on the Middle Rhine 1836–1903 . In: Nassauische Annalen 67 (1956), pp. 158-202.

- Ralph Häussler: Railways in Worms. From the Ludwig Railway to the Rhineland-Palatinate Clock. Kehl, Hamm / Rheinhessen 2003, ISBN 3-935651-10-4 .

- Bernhard Hager: "Absorption by Prussia" or "Benefit for Hesse"? The Prussian-Hessian Railway Community from 1896/97. In: Andreas Hedwig (Ed.): “On iron rails, as fast as lightning”. Regional and supraregional aspects of railway history (= writings of the Hessian State Archives Marburg. Vol. 19). Hessisches Staatsarchiv, Marburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-88964-196-0 , pp. 81–111.

- Peter Henkel: The steam railcar based on Thomas. In: Georg Wittenberger (Ed.): The railway and its history (= Darmstadt-Dieburg district. Series of publications. Vol. 2, ISSN 0179-0722 ). Friends of Museums and Monument Preservation Darmstadt-Dieburg, Darmstadt 1985, p. 69f.

- Rolf Höhmann: The buildings of the Hessian Ludwig Railway and the problems with their investigation and documentation . In: Railway and Monument Preservation. First Symposium = ICOMOS (Ed.): Booklets of the German National Committee 4. Munich [1991?], Pp. 77f.

- Wolfgang Klee: Prussian railway history . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1982. ISBN 3-17-007466-0

- Karl Klein: The Hessian Ludwig Railway or Worms, Oppenheim and the other places on the railway . Mainz 1856.

- Fritz Paetz: Data collection on the history of the railways on the Main, Rhine and Neckar. Publishing house Auerbacher Leben Knappe and Meier, Bensheim-Auerbach 1985.

- Heinz Schomann : Railway in Hessen . Railway buildings and routes 1839–1939. In: State Office for Monument Preservation Hessen (Ed.): Cultural monuments in Hessen. Monument topography Federal Republic of Germany . Three volumes in a slipcase. Volumes 2.1 & 2.2. Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1917-6 .

- Peter Scheffler: The railway in the Mainz - Wiesbaden area. = Railway junction Mainz, Wiesbaden. Eisenbahn-Kurier-Verlag, Freiburg (Freiburg) 1988, ISBN 3-88255-620-X .

- Silvia Speckert: Ignaz Opfermann (1799–1866): Selected examples of his construction work in the vicinity of the city of Mainz = housework to obtain the academic degree of a Magister [!] Artium. Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz 1989. Typed. Volume 1: Text, Volume 2: Tables. Mainz City Archives: 1991/25 No. 11.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ The members of the second chamber, Franz Philipp Aull (Mainz), Frank, Eisenhammerbetreiber (Reddighausen), Clemens Lauteren (Mainz) and Wilhelm Valckenberg (Worms) - (Döhn, p. 52) were significantly involved .

- ↑ Christian Lauteren died shortly after the election.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Döhn, p. 35.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 45f.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 48f.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 47f.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 55.

- ↑ Klein, p. 1

- ^ Rosel Spaniol: Early railway systems in Mainz (then and now). A contribution to city history and archeology = railways and museums 24th 2nd edition. Karlsruhe 1981. ISBN 3-921700-37-X , p. 9.

- ^ Otto Westermann: Young Railway in 2000-year-old golden Mainz. From the good and bad days of the Mainz Railway . Federal Railway Directorate Mainz, Mainz undated [after 1962], p. 43.

- ↑ Angela Schumacher, Ewald Wegner: Monument topography Federal Republic of Germany . Monuments in Rhineland-Palatinate 2.1 = City of Mainz. City expansions in the 19th and early 20th centuries . 2nd edition: Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 1997. ISBN 978-3-88462-138-7 . P. 84.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 39.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 40f.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 57.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 58.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 60.

- ↑ Speckert, p. 71.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 59.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 65ff.

- ↑ Speckert, p. 71.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 63.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 65ff.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 79f.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 82.

- ↑ Dietrich, p. 112ff.

- ↑ Klein, p. 1

- ^ August 24, 1853. The opening of the Mainz-Worms railway line. State Main Archive Koblenz , August 24, 1853, accessed on September 16, 2017 .

- ↑ Döhn, p. 84.

- ↑ Döhn, p. 89.

- ↑ a b Döhn, p. 85.

- ^ Albert Mühl: The Pfalzbahn . 1st edition. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-8062-0301-6 , p. 16 .

- ↑ Klein, p. 2.

- ↑ Speckert, p. 71.

- ^ Fuchs, p. 167.

- ↑ Fuchs, p. 166.

- ^ Fuchs, p. 168.

- ↑ a b Döhn, p. 90.

- ↑ Paetz, p. 57.

- ↑ http://www.amiche.de/uebersicht.html

- ^ Heinz Schomann : Railway in Hessen . Railway history and building types 1839–1999 / Railway buildings and lines 1839–1939. In: State Office for Monument Preservation Hessen (Ed.): Cultural monuments in Hessen. Monument topography Federal Republic of Germany . Three volumes in a slipcase. tape 2.2 . Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1917-6 , p. 865 .

- ^ Heinz Schomann : Railway in Hessen . Railway buildings and routes 1839–1939. In: State Office for Monument Preservation Hessen (Ed.): Cultural monuments in Hessen. Monument topography Federal Republic of Germany . Three volumes in a slipcase. tape 2.1 . Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1917-6 , p. 19th ff . (Route 001).

- ^ Heinz Schomann : Railway in Hessen . Railway buildings and routes 1839–1939. In: State Office for Monument Preservation Hessen (Ed.): Cultural monuments in Hessen. Monument topography Federal Republic of Germany . Three volumes in a slipcase. tape 2.1 . Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1917-6 , p. 501 ff . (Route 032).

- ^ Klee, p. 194.

- ↑ Klee, p. 196.

- ↑ Hager, pp. 99f, 106.

- ^ State treaty (between Hesse and Prussia) on the mutual joint management of the railroad ownership on both sides . In: Eisenbahndirektion Mainz (Hrsg.): Collection of the published official gazettes . Born in 1897, p. 29ff

- ^ Agreement on the transfer of the Hessian Ludwig railway company to the Prussian and Hessian state from 8/9 July 1896. In: Eisenbahndirektion Mainz (Ed.): Collection of the published official gazettes . Born in 1897, p. 51ff

- ↑ § 2 contract regarding the transfer of the Hessian Ludwig railway company to the Prussian and Hessian state from 8/9 July 1896. In: Eisenbahndirektion Mainz (Ed.): Collection of the published official gazettes . Born in 1897, p. 51

- ^ Chronicle of the Mainz Railway Directorate

- ↑ Eisenbahndirektion Mainz (Ed.): Collection of the published official gazettes of April 8, 1899. Volume 3, No. 16. Announcement No. 170, p. 113.

- ↑ a b Döhn, p. 88.

- ↑ Heiner - Die Stadtillustrierte von Darmstadt, August 2008, p. 11 u. 16.

- ↑ Höhmann: The Buildings , p. 78.